This paper was presented at a colloquium entitled “Science, Technology, and the Economy,” organized by Ariel Pakes and Kenneth Sokoloff, held October 20–22, 1995, at the National Academy of Sciences in Irvine, CA.

An economic analysis of unilateral refusals to license intellectual property

RICHARD J.GILBERTa AND CARL SHAPIROb

Department of Economics and bHaas School of Business, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720

ABSTRACT The intellectual property laws in the United States provide the owners of intellectual property with discretion to license the right to use that property or to make or sell products that embody the intellectual property. However, the antitrust laws constrain the use of property, including intellectual property, by a firm with market power and may place limitations on the licensing of intellectual property. This paper focuses on one aspect of antitrust law, the so-called “essential facilities doctrine,” which may impose a duty upon firms controlling an “essential facility” to make that facility available to their rivals. In the intellectual property context, an obligation to make property available is equivalent to a requirement for compulsory licensing. Compulsory licensing may embrace the requirement that the owner of software permit access to the underlying code so that others can develop compatible application programs. Compulsory licensing may undermine incentives for research and development by reducing the value of an innovation to the inventor. This paper shows that compulsory licensing also may reduce economic efficiency in the short run by facilitating the entry of inefficient producers and by promoting licensing arrangements that result in higher prices.

I.

Intellectual Property and the Antitrust Laws

In the past century, technical progress has continually transformed our society. As economists, in evaluating the role of technology in our society we naturally focus on the funding of research and development (R&D) efforts and the financial rewards to those whose R&D efforts are successful. As specialists in industrial organization, we are keenly interested in the property rights assigned to innovators. As students of antitrust policy, we are especially interested in the interaction between intellectual property law, which rewards innovators by granting them some protection from competition, and antitrust law, which seeks to ensure a competitive market system and limit the creation or maintenance of monopoly power.

Intellectual property refers to creative work protected by patents, copyrights, and trade secrets (including know-how). These three protection regimes grant different rights of exclusion. Patents confer rights to exclude others from making, using, or selling in the United States the invention claimed by the patent for a period of 17 years from the date of issue. (Legislation introduced to comply with the GATT treaty will change the patent term to 20 years from the date at which the patent application is filed.) To gain patent protection, an invention (which may be a product, process, machine, or composition of matter) must be novel, nonobvious, and useful. Copyright protection applies to original works of authorship embodied in a tangible medium of expression. Copyright protection lasts for the life of the author plus 50 years, or 75 years from first publication (or 100 years from creation, whichever expires first) for works made for hire. A copyright protects only the expression, not the underlying ideas.c Unlike a patent, a copyright does not preclude others from independently creating similar expression. Trade secret protection applies to information whose economic value depends on its not being generally known. Trade secret protection is conditioned upon efforts to maintain secrecy, has no fixed term, and does not preclude independent creation by others.

At a deep level, there is no inherent conflict between the two bodies of intellectual property and antitrust law; in the long run, intellectual property rights promote competition by rewarding innovative efforts.d But the long run is an elusive concept, and in practice, great tensions arise between intellectual property and antitrust law. Indeed, efforts by patent and copyright owners to enforce their intellectual property are often met by antitrust counterclaims: the assertion that the intellectual property owner enjoys monopoly power and is illegally protecting or expanding its market position.

Economists and antitrust scholars have long attempted to define an economically efficient tradeoff between the protection of intellectual property and the reach of the antitrust laws (1). At the foundation of this tradeoff is the extent and duration of the grant of intellectual property rights (2, 3). Should a patentee have only the narrow right to prevent the sale of a duplicate work, or should that right extend to works that embody similar ideas, and how long should such protection last? Robust conclusions are difficult to obtain, in part because the optimal patent scope depends not only on the proper level of protection for the first innovator, but also on incentives for subsequent innovations that build on, and potentially infringe on, the first patent (4).e

Closely related to the optimal scope of the grant of intellectual property protection is the question of how that grant may be exploited without running afoul of the antitrust laws. As an example, permitting owners of intellectual property to organize cartels in unrelated markets would increase the

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. §1734 solely to indicate this fact.

|

|

Abbreviation: R&D, research and development. |

|

c |

Copyright protection does not extend to “an idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work” [17 U.S.C. §102(b)]. |

|

d |

“[T]he aims and objectives of patent and antitrust laws may seem, at first glance, wholly at odds. However, the two bodies of law are actually complementary, as both are aimed at encouraging innovation, industry and competition” [Atari Games Corp. v. Nintendo of America, Inc., 897 F.2d 1572, 1576 (Fed. Cir. 1990)]. The Federal Circuit has responsibility for appeals of cases involving patent rights. |

|

e |

Scotchmer (5) and Scotchmer and Green (6) provide a framework for analyzing the incentive effects of patent scope on cumulative innovation. Merges and Nelson (7, 8) offer several historical examples of the effects of the scope of intellectual property protection on innovative performance. |

profits from invention and, therefore, enhance incentives for innovation. But such a blanket antitrust exemption for intellectual property would cause unacceptably large competitive distortions in the short run. Bowman (9) analyzes the patentantitrust tradeoff from the perspective of the one-monopoly-rent theory, which implies that there is a single profit inherent in the patent. Under this theory, efforts to leverage the patent grant into other markets do not provide the patentee with additional returns and would not be pursued except for efficiency gains. However, even under the one-monopoly-rent theory, a patentee may engage in acts that adversely affect competition (such as organizing a cartel in unrelated markets or agreeing with producers of substitute products to divide markets and raise prices).f Kaplow (11) pursues a cost-benefit test, comparing the costs of specific conduct to its benefits in enhancing investment in R&D.

Although each of these approaches generates interesting insights, none has proven adequate to provide a clear prescription for antitrust policy applied to intellectual property that differs significantly from policy in other areas of the economy. Thus, in 1988 the U.S. Department of Justice adopted the following enforcement policy: “[F]or the purpose of antitrust analysis, the Department regards intellectual property (e.g., patents, copyrights, trade secrets, and know-how) as being essentially comparable to any other form of tangible or intangible property” (12). A similar statement appears in the 1995 U.S. Department of Justice/Federal Trade Commission Antitrust Guidelines for the Licensing of Intellectual Property (13).

This paper focuses on one aspect of antitrust law, the so-called “essential facilities doctrine,” which may impose a duty upon firms controlling an “essential facility” to make that facility available to their rivals. The essential facilities doctrine has profound consequences for intellectual property protection and for competition in markets where firms own important inputs that are protected by patent, copyright, or trade secret. In the intellectual property context, an obligation to make property available is equivalent to a requirement for compulsory licensing. Some would argue that the essential facilities doctrine is one respect in which antitrust policy for intellectual property is clearly different from antitrust policy for other forms of tangible and intangible property. There is considerable case law concluding that a patentee is free to choose whether or not to license its intellectual property.g But the case law does not state that a failure to license cannot be the basis of an antitrust offense.h

Even if patents cannot be challenged under the essential facilities doctrine, the case law is much less settled in the area of copyright. Most of the recent legal battles over access to intellectual property have been in the context of computer software that is protected by copyright. Examples include cases where firms have sought access to proprietary vendor-supported diagnostic software for the servicing of the vendor’s hardware. Another example is the copying of computer software to obtain access to proprietary interface codes to facilitate the development of complementary application programs. Thus, the essential facilities doctrine, whether in the form of mandating access or in the related forms of requiring compulsory licensing or permitting copying without infringement, lies squarely at the intersection of antitrust and intellectual property law.

Section II introduces the legal concept of a unilateral refusal to deal, often addressed under the appellation of the essential facilities doctrine. Section III considers why a profit-maximizing firm might choose to deny access to an important input rather than permit open access at a monopoly price. There are many procompetitive justifications for a refusal to deal, such as contractual limitations that make it difficult for the owner of the input to ensure quality and avoid free-riding. A refusal to deal also may increase entry barriers (because competitors have to produce a substitute for the input that they cannot buy) and enhance price discrimination (if the owner of the input cannot discriminate among buyers for the sale of the input). In addition, a refusal to deal may permit higher profits because the owner of an important input may not be able to write a contract with an entrant that would compensate the firm for the loss of profits that would result from competitive entry.

Throughout this discussion, our emphasis is on the consequences of a refusal to deal for economic welfare. We argue that the welfare consequences of a refusal to deal are ambiguous and that the requirement of mandatory access may lower economic welfare in the short run as well as in the long run. Section IV discusses some recent approaches to the evaluation of demands for compulsory access that have been considered in U.S. courts and in the European Community. Section V concludes with the observation that the essential facilities doctrine does not provide a consistent legal or economic justification for the mandatory licensing of intellectual property.

The future battleground over refusals to deal is likely to be in the proper scope of intellectual property protection under the copyright laws, particularly for computer software. Rather than compel the owner of copyrighted software to license that software to others, the legal and economic issues are more likely to focus on the conditions under which the software should be protected by copyright in the first place. This is also likely to be a more productive inquiry than a policy of selective compulsory licensing.i

II.

Refusals to Deal and the Essential Facilities Doctrine

Under the antitrust laws, conduct by a firm with market power may be illegal if the effect of that conduct is to tend to create or sustain a monopoly, and if that monopoly is not the consequence of superior skill, foresight, or business acumen, or historical accident. A firm with monopoly power does not violate the antitrust laws merely by charging a monopoly price.j Nonetheless, under some instances, a refusal to deal by a firm or a joint venture with monopoly power may be deemed an antitrust offense. In other words, although antitrust law permits a firm to charge the price it pleases, the firm may be required to set some price at which it will sell to others, including rivals.

The refusal to deal label has been applied to many cases with very different competitive circumstances (19). This discussion focuses on a situation in which an integrated firm (or joint venture) controls a factor of production that is costly to reproduce and competes in another market against one or

|

f |

Baxter notes that “a promise by the licensee to murder the patentee’s mother-in-law is as much within the ‘patent monopoly’ as is the sum of $50; and it is not the patent laws which tell us that the former agreement is unenforceable and subjects the parties to criminal sanctions” (10). |

|

g |

See, for example, SCM Corp. v. Xerox Corp., 645 F.2d 1195 (2d Cir. 1981) cert, denied 455 U.S. 1016 (1982) and Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazeltine Research, Inc., 395 U.S. 100 (1969). Furthermore §271(d) of the 1988 Amendments to the Patent Act specifies that a refusal to license a patent cannot be the basis for a patent misuse claim. |

|

h |

Indeed, the recent jury verdict in Image Technical Services v. Eastman Kodak Company (Civil No. C-87–1686 BAC, March 1995) finds Kodak’s unilateral refusal to sell patented parts to be an antitrust offense. C.S. testified on behalf of Kodak in this case. See ref. 14 for an analysis of the issues involved in this and related cases. |

|

i |

Farrell (15, 16), Farrell and Saloner (17), Menell (18), and R.H. Lande and S.M.Sobin (unpublished work) offer useful perspectives on the efficient scope of protection for computer software. A recent case that raises important issues on the scope of copyright protection is Lotus Dev. Corp. v. Borland Int’l, Inc., F.3d 807 (1st Cir. 1995). |

|

j |

See, for example, United States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563, 571 (1966) and United States v. Aluminum Co. of America, 148 F.2d 416, 430 (2nd Cir. 1945). |

more firms that desire access to the factor of production. The factor of production could be a physical input or intellectual property that is owned or controlled by the integrated firm. Examples are a local telephone network, a distribution network, a patented product or process, and the control of proprietary interface standards.k The firms seeking access may be competitors in upstream, downstream, or otherwise complementary markets.

A refusal to deal by a vertically integrated firm appears on its face to adversely affect competition by denying rivals a product or service that is a necessary input for effective competition.l This is hardly a complete analysis, however, because it does not account for the incentives to create the essential input or the price at which that input can optimally be sold. Clearly, the mere fact that a firm controls an input that is valuable to its competitors cannot be sufficient to compel a duty to deal, as a firm can have many innocent reasons for refusing to supply a rival. In MCI Communications Corporation v. AT&T, 708 F.2d 1081 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 955 (1983), MCI argued that access to AT&T’s local switching equipment was essential to compete in the long-distance telephone market. The Seventh Circuit upheld a jury verdict on liability. In its decision, the court described the necessary elements of an essential facilities claim: (i) control of an essential facility by a monopolist; (ii) a competitor’s inability practically or reasonably to duplicate the essential facility; (iii) the denial of the use of the facility to a competitor; and (iv) the feasibility of providing the facility.m

These conditions do not characterize the circumstances under which compulsory access to a facility or to intellectual property would be beneficial to economic welfare. A firm may choose to deny access to an actual or potential competitor (at a price that would allow the actual or potential entrant to earn a non-negative return) for many different reasons. These include reasons that are likely to enhance economic efficiency. For example, a hardware vendor may refuse to allow independent firms to service its machines if the independents cannot ensure a desired level of service quality. Furthermore, a refusal to deal can prevent free-riding that would diminish incentives for investment and innovation.

A refusal to deal also may be motivated by the desire of the owner of an important input to prevent the entry of new competition, either in the market for the input or in the market for a product that is produced with the input. By refusing to sell an input, a potential competitor has to compete as a de novo entrant both in the market for the input and in the market for the final product. This “two-level” entry requirement may raise the cost of entry into the final product.

A refusal to deal also may enable an owner of an input to exploit its market power more effectively by promoting price discrimination in the sale of the final product. For example, a hardware vendor may refuse to accommodate independent service organizations because service is a convenient “metering” device by which the vendor can monitor and charge customers according to their intensity of use. Such price discrimination can lead to increased output by expanding sales to price-sensitive customers.n A detailed factual inquiry is needed in any given case to determine whether a refusal to deal that is based solely on improved opportunities for price discrimination reduces or enhances overall efficiency.

An owner of a necessary input also may refuse to sell or license the input to preserve its market power in the production of the final product. The owner of a necessary input would not benefit from the licensing or sale of the input unless the owner can construct a contract that compensates the owner for the loss of revenue that may result from entry. Such a contract can be difficult to construct in many circumstances. The next section focuses specifically on the incentives of the owner of an essential input to execute a contract to license the input and on the consequences of a refusal to deal for economic efficiency.

III.

Why Refuse to Deal Rather Than Set a High Price?

To better understand the market-power-preservation rationale for a refusal to deal, we employ the game-theoretic framework developed in Katz and C.S. (25). Firms 1 and 2 compete to sell a homogeneous product with initial constant marginal costs a1 and a2 and zero fixed costs. In the first stage of the game, firm 1 acquires a process innovation that lowers its marginal cost to m1<a1. In the second stage, firm 1 chooses whether to offer a license for the process to firm 2, and firm 2 chooses whether to accept or reject the license. If firm 1 licenses firm 2 (and firm 2 accepts the license), firm 2’s marginal cost (excluding any licensing fees) falls to m2 < a2. Otherwise, firm 2’s marginal cost remains at a2.

Firm 1’s decision to license the new technology to firm 2 is similar to the decision to provide access to a facility. Access is often of particular significance in network industries, for which the facility may be a common interface or proprietary standards that enable the supply of complementary network products and services.o For example, J.Church and N.Gandal (unpublished work) consider competition in a market where firms offer complementary products, such as hardware and software, and have the choice of making their products compatible with the products of a rival. In this framework, intentional incompatibility has similar effects as a refusal to deal.

When Is a Facility Essential? The legal opinions that address the subject of essential facilities do not define the technical requirements that must be satisfied for an input to be essential. Consider a production function y=f(xα,xβ), where xα, xβ are inputs into the production of y. Input α is clearly essential if f(0, xβ)=0 for any xβ, but this is not the only reasonable definition of an essential input. In most circumstances, the determination of whether an input is essential to competition will depend on the price of the input and the price of the product (or products) that use the input. At prevailing prices, an electric utility’s transmission lines may be essential to compete in the sale of electricity. But at much higher electricity prices, it may be profitable to build new transmission lines or to contract for transmission from other sources. The second prong of the MCI essential facilities test, “a competitor’s inability practically or reasonably to duplicate the essential facility,” implicitly includes a presumption about market prices in the determination of what is practical or reasonable.

We propose the following economic definition of an essential input. Consider an integrated firm that owns or controls input 1 and produces an outputy. Let pm be the monopoly price of outputy when the integrated firm faces prices w for all inputs other than input 1. Let C(y, w) be the total cost of producing outputy for an equally efficient firm that faces an infinite price for input 1 and prices w for all other inputs. We say that input 1 is essential if C(y, w) > pmy for all y.p That is, without input

|

k |

Other examples include the control of quality or safety standards [see Anton and Yao (20)]. |

|

l |

See Werden (21). Ordover, Salop, and Saloner (22) and Riordan and Salop (23) each provide an illuminating analysis of related competitive effects in the context of vertical mergers. |

|

m |

See MCI Communications Corporation v. AT&T at 1132–1134. The Supreme Court recently affirmed this general approach. “It is true as a general matter a firm can refuse to deal with its competitors. But such a right is not absolute: it exists only if there are legitimate competitive reasons for the refusal.” [Image Technical Services v. Eastman Kodak Company, 504 U.S. 541 (1992)]. |

|

n |

See ref. 24 for an analysis of how a refusal to deal, implemented by a price squeeze, can facilitate price discrimination. |

|

o |

Baker (26), Carlton and Klammer (27), D.W.Carlton and S.C.Salop (unpublished work), and H.Hovenkamp (unpublished work) discuss issues that bear on mandatory access for network joint ventures. |

|

p |

We take pm as a parameter in the definition, independent of the |

1, an equally efficient firm cannot profitably produce any level of output even if the output is sold at the integrated firm’s monopoly price. Under these conditions, without access to input 1, the equally efficient firm cannot exercise any constraint on pricing by the integrated firm.

The definition of essential can be extended to include the price of the input. Firm 2 may not be able to compete against an integrated monopolist unless the input is available at a price that is sufficiently low. But how low should the price be? A particularly inefficient firm may not be able to compete unless it can purchase an input at a price that is less than the input’s marginal cost. Our preferred definition states that an input is essential only if an equally efficient firm cannot compete when the input is not available, or equivalently, when its price is infinite.

In our simple example, we consider the innovation by firm 1 to be essential if firm 2 cannot compete without the innovation when firm 1 sets any price that is less than or equal to its monopoly price. The input in our example is the innovation. Firm 1 is a vertically integrated producer of both the input and the final output. Let p1m (m1) be firm 1’s monopoly price of the final output when its marginal cost is m1. By our definition, firm 1’s technology is essential if a2 > p1m (m1); that is, if firm 1’s technological innovation would eliminate competition when firm 1 sets a monopoly price, if firm 2 does not have access to the innovation.

When Would Firm 1 Refuse to License the Innovation to Firm 2? Firm i’s profits depend on its cost, the cost of its rival, and on the competitive circumstances of the industry. The terms of a license affect industry costs and may also influence the intensity of competition. For example, firms’ pricing decisions may depend on whether a license calls for a fixed royalty or for royalties that vary with the licensee’s output. There is a mutually acceptable license if, and only if, total industry profits when there is licensing exceed total industry profits when firm 1 does not license. Whether this is the case will depend on m1, m2, and a2, and on the form of the licensing arrangement.

Following Katz and C.S. (25), we explore the implications for licensing under two licensing regimes. In both regimes, firms 1 and 2 are Nash-Cournot competitors in the absence of a licensing arrangement. In the first regime, the firms negotiate a fixed-fee license that imposes no conditions on the firms’ choices of prices and outputs. The license requires only a fixed payment from firm 2 to firm 1. Conditional on the license, the firms compete as Nash-Cournot competitors with marginal costs m1 and m2. In the second licensing regime, the firms negotiate a royalty structure that supports the joint profit-maximizing outputs. We refer to the second regime as licensing with coordinated production.

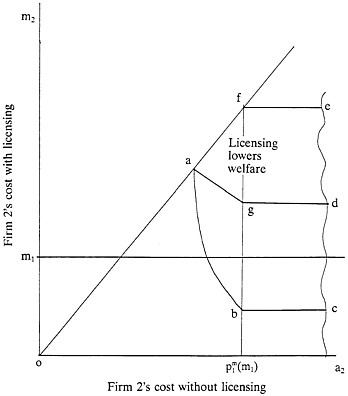

Alternative 1: Nash-Cournot Competitors with a Fixed Licensing Fee. Katz and C.S. (25) derive the conditions on m1, m2, and a2 that are necessary for firm 1 to enter into a profitable licensing arrangement with firm 2. These conditions are summarized in Fig. 1. In the area bounded by abcdef, firm 1 will refuse to license firm 2. Generally, it is profitable for firm 1 to exclude firm 2 by refusing to offer firm 2 a license when, relative to firm 1’s cost, (i) firm 2’s cost if excluded is large and (ii) firm 2’s cost with a license is not too small. Firm 1 will not choose to license an essential innovation, defined by a2 > p1m (m1), unless firm 2’s marginal cost with the license is very small. Refusals to deal are not limited to essential innovations. Even if firm 2 could compete without a license, firm 1 may choose to exclude firm 2 from the innovation unless it would substantially reduce firm 2’s cost.q

FIG. 1. Outcomes with fixed-fee licensing.

In the Nash-Cournot case with constant marginal costs, if licensing is privately rational, it is also welfare-enhancing. Licensing is privately rational when it increases industry profits. In addition, licensing lowers industry costs. In the Nash-Cournot case with constant marginal costs, total output is higher and price is lower when costs are reduced, so consumers are also better off when firm 1 voluntarily licenses firm 2.

Compulsory licensing in this context is a fixed-fee license that firm 2 will accept; that is, a royalty that is less than firm 2’s profit with the license. Compulsory licensing can increase welfare, but not always. When firm 2’s marginal cost with a license is close to firm 1’s monopoly price, and significantly above firm 1’s marginal cost, a license can decrease welfare because it substitutes high-cost production by firm 2 for lower-cost production by firm 1 (25). The area in Fig. 1 for which compulsory licensing will decrease welfare is defined by the region bounded by agdef. Thus, with fixed-fee licensing, a compulsory licensing requirement will lower welfare even in the short run if the licensee would have high costs in the absence of the license and also relatively high costs with the license compared with the licensor. This is a case in which the license is essential for the licensee to compete, but the licensee would not be a very efficient competitor.

Alternative 2: Licensing with Coordinated Production. Firm 1 will always license firm 2 if their joint-maximizing profits exceed their stand-alone profits and if the license agreement can enforce the joint-maximizing outcome. Joint profit-maximizing licensing arrangements can be implemented in different ways, including a suitably defined two-part tariff or a forcing contract that requires each firm to pay a penalty if its output deviates from the contracted level (which requires that the firms be able to monitor each others’ outputs). In our example with firms that have constant marginal costs, only the firm with the lower marginal cost will produce in a joint profit-maximizing arrangement. Thus, with m2 > m1, firm 1 in

|

|

nonintegrated firm’s output. More generally, price will vary with the nonintegrated firm’s output and can be a further constraint on the nonintegrated firm’s profits. |

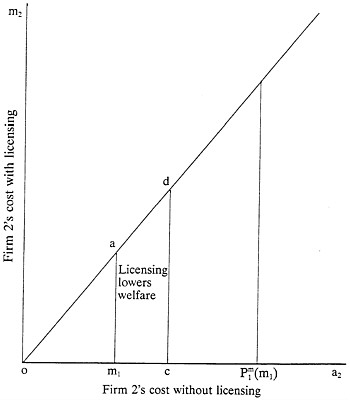

FIG. 2. Outcomes with coordinated production.

effect pays firm 2 to exit the industry.r In more general circumstances with increasing marginal costs, both firms may produce at positive levels in a coordinated licensing arrangement.

A joint profit-maximizing license may increase economic welfare in the short run by achieving more efficient production. However, when firms 1 and 2 produce products that are substitutes, a joint profit-maximizing license also permits collusion. Fig. 2 shows the range of firm 2’s marginal costs for which licensing reduces welfare in the short run. This is the area bounded by a, m1, c, and d in Fig. 2. In this regime, licensing lowers welfare if firm 2’s costs are not too large without the license. Licensing raises welfare in this case if the licensee’s cost without a license is high, but not so high that it cannot compete.

When licensing can achieve coordinated production, the firms will have private incentives to reach an agreement. There is no scope for compulsory licensing in this situation. Nonetheless, compulsory licensing, if available, can be a source of inefficiency. Firm 2 could use compulsory licensing as a threat to wrestle more favorable licensing terms from firm 1.

The jointly profit-maximizing licensing arrangement high-lights the importance of complementarities, network externalities, and other effects, such as product differentiation, in the evaluation of the benefits of compulsory licensing. In the simple example where firms 1 and 2 produce homogenous products, licensing that coordinates production reduces welfare for many parameter values. However, if the products produced by firms 1 and 2 are complements, licensing with coordinated production would eliminate double-marginalization and result in both greater profits and lower prices for consumers.

Implications for Compulsory Licensing. The incentives for and consequences of licensing differ sharply in the two regimes, which differ only in the contract that the licensor can enter into with the licensee. In the first regime, there are efficient licenses that are not voluntary. For this reason, compulsory licensing can increase welfare in the short run. However, there are also licensing arrangements involving high-cost licensees that are neither voluntary nor efficient. Compulsory licensing under such circumstances leads to lower welfare in the short run. The second regime poses a risk of overinclusive licensing. Thus, in the first regime, the policy dilemma raised by compulsory licensing is how to avoid compelling licenses to high-cost licensees. In the second regime, the dilemma is how to prevent firms from entering into license agreements when those firms would be reasonably efficient competitors on their own.

Compulsory licensing rarely imposes a specific form for the license, other than the requirement that a royalty be “reasonable.” This lack of definition complicates the assessment of compulsory licensing because the consequences of a compulsory license for economic efficiency depend, inter alia, on the form of the licensing arrangement. We have considered the polar cases of a fixed-fee license and a license that achieves coordinated production. A royalty that is proportional to the licensee’s sales has economic effects that are similar to the effects of a fixed-fee license if the royalty rate is small. A fixed-fee license has a zero royalty rate and the fixed-fee itself has no consequence for total economic surplus because it is only a transfer of wealth between the licensee and the licensor. Thus, a small royalty that is proportional to sales is likely to raise the same types of concerns that were identified for fixed-fee licenses. Specifically, even a “royalty-free” license can harm economic efficiency by facilitating the entry of a high-cost firm. Of course, if the royalty rate is large, the costs imposed on the licensee may be large enough to cause de facto exclusion, so that the compulsory license would not provide economically meaningful access.

These results pose obvious difficulties for designing a public policy that may require compulsory access to a firm’s technology. Unless compulsory access policies are designed and implemented with great care, firms will have incentives to misrepresent their costs to obtain a license, and compulsory licensing may not improve economic welfare even in the short run. It is considerably easier to state the theoretical conditions under which a firm will refuse to deal than to determine if compulsory licensing is beneficial in particular market circumstances.

How Does an Obligation to License Affect Incentives for R&D? In general, the effects of licensing on the incentives to invest in R&D are complex and may lead to under- or overinvestment in R&D (25). Conceptualizing investment in R&D as a bid for an innovation produced by an upstream R&D laboratory, we note that a compulsory licensing requirement is likely to reduce the incentives for R&D for two reasons. First, a compulsory license reduces the profits of the winning bidder by forcing the winner to license in situations where it is not privately rational to do so. Second, compulsory licensing is likely to lower the value of the winning bid because it increases the profits of the losing bidder. Under compulsory licensing, the losing bidder is assured that it will benefit from the innovation, assuming the owner of the technology is compelled to license the technology at a price that the licensee would be willing to pay. The size of the winning bid is determined by a firm’s value of owning the technology, less the value to the firm if the technology is in the hands of its rival. Compulsory licensing lowers the first component and raises the second.

Thus, compulsory licensing can have two negative effects on economic welfare. It can reduce welfare in the short run by compelling inefficient licensing. It also can reduce welfare in the long run by reducing incentives for innovation. In general, the effects of compulsory licensing may act to increase or decrease economic welfare in both the short and the long run, depending on specific parameter values and the dynamics of

|

r |

The royalty arrangement has to prevent firm 2 from entering as an inefficient producer, which may require a provision restricting firm 2 from using its own technology (28). |

competition. It is this indeterminacy that makes compulsory licensing a potentially very costly public policy instrument.

IV.

Recent Legal Approaches to Analyzing Refusals to Deal

Legal opinions addressing unilateral refusals to deal have attempted to analyze the requirement to provide access either directly as an essential facility by applying the MCI factors or indirectly by evaluating the effects and motivation for the alleged anticompetitive conduct. A recent example of the latter approach is in Data General Corp. v. Grumman Systems Support Corp., 36 F.3d 1147 (1st Cir. 1994). Data General sold mini-computers and also offered a line of products and services for the maintenance and repair of the computers that it sold. Grumman competed with Data General in the maintenance and repair of Data General’s computers. In addition to other antitrust claims, the court addressed whether Data General illegally maintained its monopoly in the market for the service of Data General computers by unilaterally refusing to license its diagnostic software to Grumman and other competitors.

The court considered whether Data General’s refusal to license “unjustifiably harm the competitive process by frustrating consumer preferences and erecting barriers to competition.” It concluded otherwise because, despite a change in Data General’s policy in dealing with independent service organizations, there was no material effect on the competitive process. Data General was the dominant supplier of repair services for its own machines, both when it chose to license its diagnostic software to independent service organizations and later, when it chose not to license independents.

The court’s analysis in Data General failed to address the central economic question, which is whether a policy that requires Data General to license its software to independent service organizations would enhance economic welfare. Moreover, a focus on preserving the competitive process raises obvious difficulties that have been emphasized by several authors. Areeda (29) notes that “lawyers will advise their clients not to cooperate with a rival; once you start, the Sherman Act may be read as an anti-divorce statute.” Easterbrook (30) makes a similar argument and notes the contradiction posed by policies that promote aggressive competition on the merits, which may exclude less efficient competitors, and a policy that imposes an obligation to deal.

Other countries have not been more successful in arriving at an economically sound rationale for compulsory licensing. An example is the recent Magill decision by the European Court of Appeals. The case was the result of a complaint brought to the European Commission by Magill TV Guide Ltd. of Dublin against Radio Telefis Eireann (RTE), Independent Television Publications, Ltd. (ITP), and BBC. The case involved a copyright dispute over television program listings. RTE, ITP, and BBC published their own, separate program listings. Magill combined their listings in a TV Guide-like format. RTE and ITP sued, alleging copyright infringement.

The Commission concluded that there was a breach of Article 86 of the Treaty of Rome (abuse of dominant position) and ordered the three TV broadcasters to put an end to that breach by supplying “third parties on request and on a non-discriminatory basis with their individual advance weekly program listings and by permitting reproduction of those listings by such parties.” The European Court of First Instance upheld the Commission’s decision, as did the European Court of Appeals.

The decision by the European Court of Appeals stated that the “appellants’ refusal to provide basic information by relying on national copyright provisions thus prevented the appearance of a new product, a comprehensive weekly guide to television programmes, which the appellants did not offer and for which there was a potential consumer demand. Such refusal constitutes an abuse…of Article 86.” Moreover, the court said there was no justification for such refusal and ordered licensing of the programs at reasonable royalties.

This is an expansive rationale, in the absence of a clear definition of what constitutes a valid business justification. The analysis discussed in this paper could be extended to consider the economic welfare effects of compulsory licensing of a technology that enables the production of a new product. The results described here are likely to apply to the new product case, at least for circumstances in which the licensee’s and the licensor’s products are close substitutes. Thus, it is likely that compulsory licensing to enable the production of a new product would have ambiguous effects on economic welfare, even ignoring the likely adverse consequences for long-term investment decisions.

The analysis in this paper is unlikely to support the argument that economic welfare, either in the short run or in the long run, is enhanced by an obligation to license intellectual property (or to sell any form of property) whenever such property is necessary for the production and marketing of a new product for which there is potential consumer demand. It should be noted, however, that this analysis focuses on the effects of compulsory licensing on economic efficiency as measured by prices and costs. It does not attempt to quantify other possibly important factors, such as the value of having many decision-makers to pursue alternative product development paths. Merges and Nelson have argued that the combination of organization failures and restrictive licensing policies have contributed to inefficient development of new technologies in the past, and that these failures could have been ameliorated with more liberal licensing policies (31).

V.

Concluding Remarks

The essential facilities doctrine is a fragile concept. An obligation to deal does not necessarily increase economic welfare even in the short run. In the long run, obligations to deal can have profound adverse incentives for investment and for the creation of intellectual property. Although there is no obvious economic reason why intellectual property should be immune from an obligation to deal, the crucial role of incentives for the creation of intellectual property is reason enough to justify skepticism toward policies that call for compulsory licensing. Equal access (compulsory licensing in the case of intellectual property) is an efficient remedy only if the benefits of equal access outweigh the regulatory costs and the long run disincentives for investment and innovation. This is a high threshold, particularly in the case of intellectual property.

It should be noted that in Data General Corp. v. Grumman Systems Support Corp., the court analyzed Data General’s refusal to deal as a violation of section 2 (monopolization) without applying the conditions that have been specified in other courts as determinative of an essential facilities claim. Had the court done so, it might well have concluded that Data General’s software could not meet the conditions of an essential facility because it could be reasonably duplicated. The purpose of patent and copyright law is to discourage such duplication so that inventors have an incentive to apply their creative efforts and to share the results with society. In this respect, compulsory licensing is fundamentally at odds with the goals of patent and copyright law and should be countenanced only in extraordinary circumstances.

Despite the adverse incentives created by a refusal to deal, whether for intellectual or other forms of property, courts appear to view with suspicion a flat refusal to deal, even while they are wary of engaging in price regulation under the guise

of antitrust law.s The fact remains, however, that the courts cannot impose a duty to deal without inevitably delving into the terms and conditions on which the monopolist must deal.t This is a typically a hugely complex undertaking. The first case in the United States that ordered compulsory access, United States v. Terminal R.R. Ass’n, 224 U.S. 383 (1912) and 236 U.S. 194 (1915), required a return visit to the Supreme Court to wrestle with the terms and conditions that should govern such access (26).u The dimensions of access are typically so complex that ensuring equal access carries the burden of a regulatory proceeding. F.Warren-Boulton, J.Woodbury, G.Woroch (unpublished work) and P.Joskow (unpublished work) consider alternative institutional arrangements for markets with essential facilities, such as structural divestiture and common ownership of bottleneck facilities. However, none of these institutional alternatives is without significant transaction and governance costs that are difficult to address even in a regulated environment.

With specific reference to intellectual property, the future battleground over a firm’s obligation to deal with an actual or potential competitor is likely to concentrate in the domain of computer software. This is where competitive issues have surfaced, issues such as access to diagnostic tools that are necessary to service computers,v access to software for telecommunications switching,w and access to interface codes that are necessary to achieve interoperability.x This debate is more likely to focus on what is protect able under the copyright laws than on what protectable elements are candidates for compulsory licensing. In a utilitarian work such as software, it is particularly difficult to ascertain the boundaries between creative expression that is protectable under copyright law and other, functional, elements. Thus, it is more likely that essential facilities will give way to the prior issue of determining the scope of property over which firms may claim valid intellectual property rights. This seems the more sensible direction for public policy. Our analysis has not demonstrated a clear understanding of the conditions that lead to the conclusion that the owner of any type of property should, for reasons of economic efficiency, be compelled to share that property with others. A more productive channel of inquiry appears to us to focus on the types of products that justify intellectual property protection and the appropriate scope of that protection.

We are grateful for comments by Joe Farrell and seminar participants at the University of California at Berkeley.

|

s |

Of course, many monopolists, such as local telephone companies, face price regulation, but not under antitrust law. |

|

t |

For example, in D&H Railway Co. v. Conrail, 902 F.2d 174 (2nd Cir. 1990), the Second Circuit Court of Appeals found that Conrail’s 800% increase in certain joint rates raised a genuine issue supporting a finding of unreasonable conduct amounting to a denial of access by Conrail. Compare this, however, with Laurel Sand & Gravel, Inc. v. CSX Transp., Inc., 924 F.2d 539 (4th Cir. 1991), in which the plaintiff, a shortline railroad, received an offer from CSX for trackage rights but alleged that the rate quoted was so high as to amount to a refusal to make those trackage rights available. The Fourth Circuit found on these facts that there could be no showing that the essential facility was indeed denied to the competitor. |

|

u |

The Terminal Railroad Association was a joint venture of companies that controlled the major bridges, railroad terminals, and ferries along a 100-mile stretch of the Mississippi River leading to St. Louis. Reiffen and Kleit (31) argue that the antitrust issue in Terminal R.R. was not the denial of access but rather the horizontal combination of competitors in the joint venture. |

|

v |

See, for example, Data General, discussed above, and Image Technical Services, Inc. v. Eastman Kodak Company, 504 U.S. 541 (1992). |

|

w |

The MCI case is an example. |

|

x |

See, for example, Atari Games Corp. v. Nintendo of America, Inc., 897 F.2d 1572, 1576 (Fed. Cir. 1990). |

1. Nordhaus, W. (1969) Invention, Growth and Welfare: A Theoretical Treatment of Technological Change (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA).

2. Gilbert, R.J. & Shapiro, C. (1990) Rand J. Econ. 21, 106–112.

3. Klemperer, P. (1990) Rand J. Econ. 21, 113–130.

4. Kitch, E. (1977) J. Law Econ. 20, 265–290.

5. Scotchmer, S. (1991) J. Econ. Perspect., Winter, 5, 29–41.

6. Scotchmer, S. & Green, J. (1990) Rand J. Econ. 21, 131–146.

7. Merges, R.P. & Nelson, R.R. (1990) Columbia Law Rev. 90, 839–916.

8. Merges, R.P. & Nelson, R.R. (1994) J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 25, 1–24.

9. Bowman, W. (1973) Patent and Antitrust Law (Univ. Chicago Press, Chicago).

10. Baxter, W.F. (1966) Yale Law J. 76, 277.

11. Kaplow, L. (1984) Harvard Law Rev. 97, 1815–1892.

12. U.S. Department of Justice (1988) Antitrust Enforcement Guidelines for International Operations, Nov. 10.

13. U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission (1995) Antitrust Guidelines for the Licensing of Intellectual Property, April 6.

14. Shapiro, C. (1995) Antitrust Law J. 63, 483–511.

15. Farrell, J. (1995) Stand. View June, 46–49.

16. Farrell, J. (1989) Jurimetrics J. 30, 35–50.

17. Farrell, J. & Saloner, G. (1987) in Product Compatibility as a Competitive Strategy, ed. Gabel, H.L. (North-Holland Press), pp. 1–21.

18. Mennell, P. (1987) Stanford Law Rev. 39, 1329–1372.

19. Glazer, K.L. & Lipsky, A.B., Jr. (1995) Antitrust Law J. 63, 749–800.

20. Anton, J.J. & Yao, D.A. (1995) Antitrust Law J. 64, 247–265.

21. Werden, G. (1988) St. Louis Univ. Law Rev. 32, 433–480.

22. Ordover, J., Saloner, G. & Salop, S.C. (1992) Am. Econ. Rev. 80, 127–142.

23. Riordan, M.H. & Salop, S.C. (1995) Antitrust Law J. 63, 513–568.

24. Perry, M.K. (1978) Bell J. Econ. 9, 209–217.

25. Katz, M.L. & Shapiro, C. (1985) Rand J. Econ. 16, 504–520.

26. Baker, D. L (1993) Utah Law Rev. Fall, 999–1133.

27. Carlton, D. & Klammer, M. (1983) Univ. Chicago Law Rev. Spring, 446–465.

28. Shapiro, C. (1985) Am. Econ. Rev. 75, 25–30.

29. Areeda, P. (1990) Antitrust Law J. 58, 850.

30. Easterbrook, F.H. (1986) Notre Dame Law Rev. 61, 972–980.

31. Reiffen, D. & Kleit, A. (1990) J. Law Econ. 33, October, 419–438.