The Charrette Process: a Tool for Achieving Design Excellence

Thomas Grooms

General Services Administration

I will not talk to you today about a new technique but instead about something old. We often come to conferences to hear about new developments. But sometimes it is useful to look at something we already know in a new way.

The term charrette is not well known among lay people or engineers, but it is familiar to architects. A charrette is an intensive brainstorming session over several days that focuses on a particular issue or problem. A charrette can be a very useful tool to develop the right framework to support design and construction excellence.

When we build federal facilities, we often have trouble seeing the forest for the trees. Each member of the project team concentrates on his or her aspect of the project—budget and financing, procurement, site analysis and acquisition, design development, or cost and construction management. We develop elaborate timelines and production schedules. It is all very compartmentalized and linear thinking. We hope that when we finish putting all the trees in a row, we will have a beautiful forest, or, in the case of a building, a beautifully functioning facility that is built on time and within budget. Often, we find out too late, however, that we don't have the ''object of our desire''—a quality facility.

The reason is that a critical element was missing at the very beginning of the project: a shared vision of what the project is, can be, and should be. Without this shared vision to provide a framework for decision making throughout the project, the ultimate goal—a quality facility—is often unfulfilled.

A facility must obviously be more than a weather-tight, economical box. It must enhance the users' quality of life, enable them to work productively, and be a civic structure that inspires and adds value to the community.

While each participant involved in producing a facility is an expert and has a vision, this vision is generally fairly narrow. I would suggest that the charrette is a valuable, economical tool to arrive at a broad shared vision, and is particularly helpful in developing an informed client.

It is important to get the best design talent possible, but if the client has an inadequate vision at the start, you may not get the best work out of the architect. In the end, it is the client's facility not the architect's. The architect's vision is very important for a quality facility, but the facility must meet the client's needs.

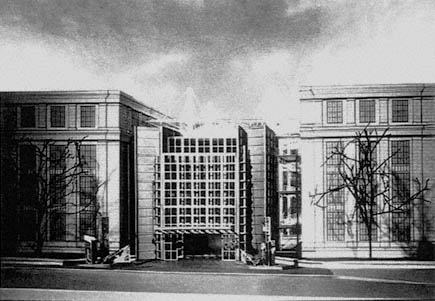

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing Facade

To illustrate, I will describe a particular charrette I organized for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in Washington, D.C. Located between 14th and 15th streets, Southwest, by the Tidal Basin, the bureau is an anomaly in Washington. It is a factory within the monumental core of the city. Its 15th Street side is neoclassical in design. However, its 14th Street side is industrial in character (Figure 1). For the facility to be

Figure 1.

Existing 14th Street Side of the Bureau of Engraving and

Printing.

maintained to current standards for security and environmental concerns, its exterior often requires altering. Two of the three open courts on the 14th Street side are slowly being filled in with new mechanical equipment. These changes cause concern to the Commission of Fine Arts and National Capital Planning Commission, who must approve them.

Over the years, the bureau has taken many proposed changes to these reviewing commissions. Several years ago, these two commissions—worn down by what they saw as piecemeal changes that harmed the architectural integrity of the building and the monumental core area—approved a new wastewater treatment plant, contingent on the bureau's development of a long-term urban master plan.

Thus, the Southwest Gateway Project was born. The bureau is interested in turning the 14th Street side, the industrial side, into a gateway into Washington. Fourteenth Street is a main entrance into the city's monumental core from Virginia. What was once the back door of the bureau has become the front door, providing, in addition to service access, the entrance for 500,000 visitors a year. The bureau asked me to help develop this master plan and guidelines on how to proceed with future alterations to the building and simultaneously provide a new visitor experience. I responded by assembling a charrette team. The six-person national design team included two architects, two urban planners, one historic preservationist, and one landscape architect. We met for two days with bureau officials, including the Director, facilities manager, and staff architects.

The first day of the charrette was devoted mainly to presentations from the bureau's chief engineer and facilities manager, and from the public relations staff about tour needs. We heard from the National Park Service, which controls the land on the 15th Street side of the building, and from the architects of the Holocaust Museum, which was being built next door. The bureau expected many more visitors once the Holocaust Museum opened. We also heard from Arthur Cotton Moore, the architect for the Portals project, a mixed-use complex across the street from the bureau's annex. We wanted to find out about all the construction projects happening in the area and how the bureau might be affected by them.

As part of the charrette, we had a very detailed site visit. The bureau is not an easy place to go through. One needs to understand how the production facility works and the tremendous security issues involved.

The charrette team made 26 recommendations to the bureau. These ranged from the type of design team and design process that the bureau should engage for the project, to a number of urban, architectural, and landscape design questions. (A professor of architecture served as the group's rapporteur and drafted its report.)

Most important, the charrette gave the bureau a clear vision of the project and what design could do to help meet their needs. One of the biggest issues was whether the 14th Street side should be given a classical facade or still be recognized as an industrial building. The team agreed unanimously that a balanced expression of monumental and technical images would best capture the bureau's unique work.

What did the bureau do with our recommendations? I helped them develop a scope of work for Phase I—or a concept development of the master plan, including the visitor center. The bureau then gave $30,000 each to three of their task order architect-engineer contractors to form a multidisciplinary team and develop a design concept based on the charrettes recommendations. I then brought back three members of the charrette team to evaluate these three concepts based on the guidelines in the charrette report. The team recommended one of the concepts to the bureau, which the bureau endorsed. This concept has been developed and recently received final approval from the Commission of Fine Arts and the National Capitol Planning Commission (Figure 2).

The two open courts on the 14th Street side that were being filled in with mechanical equipment will now have huge screens set back from the street to hide new equipment. The screens can be raised for easy installation of equipment. In the center court of the building will be a new free-standing visitor center to replace the old visitors bridge.

I do not mean to suggest that a two-or three-day charrette is the be-all and end-all for achieving design excellence. But I do believe it is a very inexpensive and flexible tool to help establish the vision and framework required to produce a quality facility. The charrette team reviewers have helped keep the bureau and architect on track and focused on the big picture. The team has no vested interest except in the quality and design excellence of the project. They can say things to the architect or contractor that the bureau is unwilling to say to those they work with every day; the charrette team can also say things to the bureau that the architect cannot say to its client. In this way, the charrette members perform a very useful communication function.

The charrette is also fairly inexpensive. The bureau charrette cost $15,000, including the production of the report. The three design reviews to date cost $6,000. After several more reviews, the bureau will have spent less than $25,000—less than one-half of one percent of the estimated design and construction cost of the project.

The charrette process dovetails with the basic goal of the General Services Administration's (GSA) Design Excellence Program: finding the best design talent. A GSA limited design competition for a new courthouse in Beckley, West Virginia, used private sector peer reviewers to help select the best design talent and to review the architect's concept development. The process was very similar to the one used for the bureau project.

Charrettes are a very flexible tool. While they are probably most useful at the beginning of a project, they can also be used very effectively at other stages.

Achieving a Sensitive Redesign: Department of Housing and Urban Development Plaza

I will briefly describe another charrette I organized for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in Washington, D.C. GSA, which owns and manages the building, was about to tear up the plaza in front of HUD for a waterproofing project. Water was leaking into the garage below. GSA was about to sign the contract when the Secretary of HUD said, since you will be tearing up the plaza, why not redesign it for better employee and community use?

GSA rose to the occasion to meet its client's needs and asked me to organize a charrette to develop ideas and guidelines for the plaza's redesign.

The HUD building and plaza were designed by the acclaimed modern architect Marcel Breuer and his partner Herbert Beckhard. The building was finished in 1968, one of the first completed under President Kennedy's "Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture." When President Johnson dedicated the building, he challenged Americans to "create a nation that will always be like this building—bold and beautiful." The redesign project was therefore an architecturally sensitive one. There were many viewpoints to reconcile in any shared vision for the new plaza.

Again, I put together an interdisciplinary team: an urban planner, architect, architectural historian, landscape architect, artist, and public

performance producer, as well as HUD and GSA staff. Additionally, I included the Executive Director of the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities, the Executive Director of the National Capital Planning Commission, and a member of the Commission of Fine Arts. The 38 guidelines and recommendations, that the charrette team formulated were used by a landscape architect engaged by GSA to put together a project team and develop three concepts for the plaza. The charrette team met several months later to review the concepts and recommend one to GSA and HUD. This design was recently approved by the Commission of Fine Arts and the National Capital Planning Commission. The Garden Scheme, as it is called, will have some permanent structures; others will be on tracks and can be moved around for different kinds of events and seating on the plaza.

This relatively modest redesign will enhance the quality of the facility for everyone who uses it. But it probably would never have been approved without the charrette.

Charrettes can be extremely useful when an agency is reducing staff, redesigning, or moving to new space. A charrette is an excellent vehicle for developing layouts to increase worker productivity or encourage collaboration and communication.

Elements of a Successful Charrette

Putting together a successful charrette is a challenge. There are several essential elements, which are obvious once pointed out. One is what I call commitment. A successful event cannot be organized without the full, open, and enthusiastic commitment of the client agency and construction agency's staff. Hidden agendas can completely undermine the charrette, as can staff resentment over the advice of outsiders. Unless the individuals responsible for executing the project are committed to the charrettes objectives and willing to suspend preconceived ideas about the project, the charrette will fail. While the agency staff must provide a reality check for the national team members, they must also be willing to entertain a wide range of new ideas.

Second, all the right players from the agencies must participate. By this I mean top agency officials who must champion the project and shepherd it through the budgetary, administrative, and legal difficulties it must overcome. For the Bureau of Engraving and Printing project, the

Director of the Bureau participated. At HUD, the Assistant Secretary for Administration participated, which made feasible the charrette recommendation that most surface parking be eliminated (other staff had said this was not possible). At the same time, the group should not number more than 15 or 16, to develop the necessary rapport and intimacy that allows easy communication.

Third, the agency must clearly define its goals and the issues to be addressed. The agency also must put together appropriate materials for the national team to review prior to meeting. This reduces the time it takes to familiarize the national team with the project. I have found that the national team members always have a much broader view than the narrower issues of concern to the client agency staff. The first few hours of the meeting are often free form, with the agency people wondering why they brought in these outsiders. But I can assure you, by the end of the two or three days, the national team comes up with many good recommendations about the agency concerns and has addressed a number of other issues the agency staff had not even thought about.

Fourth and finally, determining the composition of the national team is the most demanding part. The team should represent a very diverse group of people in terms of expertise, geographical base, and ethnic background. You are never sure what the dynamics of the group will be, because these people probably do not know each other. It is remarkable that landscape architects rarely talk to architects, nor architects to urban planners.

I usually select five to six people for the national team, including two who I have tried and tested in previous charrettes or awards juries. Bringing in new people, however, is what makes the group interesting. To identify these people, I rely on recommendations or select those whose work I have admired.

In closing, let me note that charrettes are really about two things: possibilities and communication. A charrette brings the two together to create a shared vision for the project that provides a framework for decision making throughout the project and for the better communication and collaboration of everyone involved.