Achieving Outstanding Design Efficiently

Ed Feiner

General Services Administration

As the symposium title indicates, we are at a turning point. The government is changing. We will be doing things differently. We will very likely be doing fewer things, with fewer of us to do them.

GSA and the Public Buildings Service

The General Services Administration (GSA) has had a good head start in this trend. We began our personnel reductions back in 1981, and we have gone through all of the right sizing, downsizing, and whatever sizing there is, over the last 15 years. When I came to GSA as Division Director for Design Management in 1981, GSA had 41,000 people. We are now about 16,000. The Public Buildings Service, GSA's largest division, stands at about 8,000, a 60 percent decrease in personnel in the last 15 years.

Over that same period, nevertheless, our construction program has grown from a budget of about $400 million annually, primarily for repair, alteration, and maintenance of inventory projects, to a program of about $1.2 billion per year. If you consider all ongoing projects, we now have about $9 billion of work in progress at any time.

How are we managing it? We have had to work smarter, out of necessity more than anything else. But in fact we are working relatively well.

GSA's Public Buildings Service is known as the government's landlord. We house about 50 percent of the federal workforce, in about

260 million square feet of space. We have built many different building types—including office buildings, courthouses, and museums (including most of the Smithsonian buildings), and border stations. We recently took on the World War II Memorial, a $100 million project that will be sited on the axis between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument on the Mall. It will be a very challenging project and will be based on a nationwide design competition. Generally, we work for other clients, such as agencies and branches of government like the courts, rather than for ourselves.

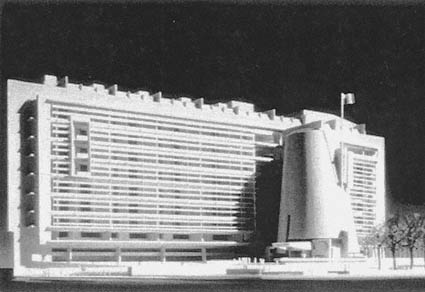

Public Buildings Service projects vary from very small to enormous. In a few days, we will be signing a contract to construct a Richard Meier-designed, 900,000 square foot courthouse, which will be one of the largest buildings on Long Island, New York (Figure 1). Generally,

Figure 1:

Model for Long Island Courthouse Designed by Richard Meier.

our buildings are more modest. Our last major building program, the purchase contract program through which GSA built roughly 70 buildings in about 10 years, was really substantial at the time. It represented the growth of federal government and the Great Society programs of the Johnson and Nixon years. The results of that program were generally not very good. Many of our buildings of that period were either glass boxes or precast concrete boxes. We offered a choice! The main objective was build it fast and build it cheap. But we did learn a lot from this experience. Cheap is not always least cost in the long run for any organization.

This issue is worth further discussion. The fact is that the life-cycle cost distribution for a typical service organization is about 3 to 4 percent for the facility, 4 percent for operations, 1 percent for furniture, and 90 to 91 percent for salaries. If we can leverage our 3 to 4 percent contribution to improve the productivity of the workplace, we can have a very dramatic effect on those representing the 90 to 91 percent of costs. We do consider the quality of the workplace environment to be very important, particularly as the federal government streamlines and downsizes.

The Early Design Quality Program

At GSA, we have been thinking about this issue for a long time. About 15 years ago, the Public Buildings Service began what was called at that time a design quality program. It was predicated on now very run-of-the-mill ideas: programming, which we defined then as problem identification; design and design review, particularly owner review and ensuring that the design meets the requirements of the owner and occupants; and post-occupancy evaluation, to test the criteria used to get the results that were programmed. Finally, we initiated a major research and demonstration project program. Some of these buildings are built now, with post-occupancy evaluations recently completed.

During the last 10 years, we did a good amount of research. The resulting publications (available from the National Technical Information Service in Springfield, Virginia) cover interim design guidelines for automated offices, and productivity enhancements.

The problem with the concept of productivity is, of course, that no one has been able to quantify it. We have tried. Some of the information in our reports is quite useful.

One of the first things I did at GSA, when we were beginning to

look at systems furniture, was to try to demonstrate a cost advantage to using one versus another type of systems furniture. It got down to calculating how often and for how long someone would be interrupted if the phone rang audibly on the other side of the systems furniture. There are many ways to address productivity, though there is no definitive method. Nevertheless, we will continue to try.

Advanced Technology Program

During the mid-1980s, we developed five major buildings around the country, to take advantage of emerging and proven technologies designed to improve the workplace environment. We used some very sophisticated and extensive design programming for these projects. Three of these buildings were new construction projects and two were repair and modernization amounting to total overhaul of existing federal buildings. These buildings included the Bonneville Power Authority in Portland, Oregon; the Long Beach Federal Building in Long Beach, California; and the Army Records Center in Overland, Missouri. The Bonneville facility was the first building in which we made a conscious effort to integrate an atrium with the working area. The offices actually look out right onto the atrium, which is also used as an auditorium.

The Mart Building in St. Louis was a major retrofit, and the Oakland Federal Building, which came immediately afterward, though not part of the program, met all the advanced technology requirements. These were a raised floor, or access floor, fiberoptics capability, control systems that were monitored throughout, with elevators, heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC), and other systems all on computer-aided design (CAD) and coordinated from one room. All these buildings are built and occupied now, and we have done several post-occupancy evaluations. The post-occupancy evaluation program is not meant to ask whether a building was built right, but to validate the design criteria and to test the design solutions. The worst way to proceed, in a time of reduced resources, is by doing the same stupid things over and over again. There is something to be said for investing in evaluation, to see whether you could have done something better, and whether the criteria should be changed to improve the performance.

One needed feature identified in our early post-occupancy evaluations was the access floor. Since government tenants move very

frequently (almost every 18 months), the flexibility for adjustments provided by access floors is a major advantage. As part of our requirements, we do specify some form of an electrified system in the floor, particularly for general office space. A 1981 General Accounting Office audit commended our post-occupancy evaluation approach.

GSA's Design Excellence Program

I also want to address GSA's Design Excellence Program. This program is not really a prescriptive program, but an attitude, a cultural change. Its main thrust is to achieve the highest quality possible within the resources available. The first step—as any architect will tell you—is to pick the right architect. While I may be a bit partial in this department, I do believe that, without the right architect, you get no place.

We therefore considered the architect selection process to be a very important part of design excellence. We brought in leaders from the architectural field, the American Institute of Architects, and the architects who were working on our program, and we asked "what's wrong with what we do?" They were very kind to tell us what was wrong with what we did. And within about two months, we completely reformed what we did.

At that same time, it was clear that we no longer had the human resources to do things the way we had in the past. In a typical architect-engineer (AE) selection, firms would submit the required standard forms (SFs 254/255), reflecting the entire team's qualifications, from the acoustician to the hydrologist—everyone you could imagine. GSA would then have a very thick stack of forms to review. And that was simply the first submission. The HVAC consultant probably received as much weight as the lead architect in that first phase of the selection process.

We decided that this is not a good way to go. We wanted to make sure that of the teams to make the first cut, every one of them would have a first-class designer. And, because we didn't have hundreds of thousands of people to review these materials, we decided we wanted a submission package no more than one-quarter-inch thick, something along the lines of a portfolio. The main objective of the review would be to determine the design talent of the lead designers and their immediate firms rather than the whole teams.

In the second phase, we interview the entire team, and review their qualifications as required by the Brooks Act. In this way we are assured

that the team has all the "horses" to efficiently and effectively execute the design.

The results of the Design Excellence Program are beginning to take shape. Richard Meier, selected under the Design Excellence Program, has designed a new courthouse for us, for Phoenix, Arizona, now in the working drawing stage. This building has won a Progressive Architecture Award, the first time this prestigious award has been won by GSA and probably by any federal agency. Progressive Architecture gave only two awards this year worldwide. Our courthouse is quite an exciting building.

Higher Quality at Lower Cost

Can you achieve design excellence in a period of diminishing resources? We benchmark the cost of all our projects. The approach is not prescriptive in the sense of a design budget, but is rather more like a planning budget.

All of the buildings in our program are cost-benchmarked. The benchmarks are based on the R. S. Means Company indices and other construction indices for every location in the country. Our construction costs are consistent with those of private sector buildings whose functions can be reasonably compared. Costs for the new regional Internal Revenue Service headquarters in New Carrollton, Maryland, clearly an exceptional design, are well within the range of the costs for privately developed general purpose office space in the Washington, D.C., area. And we will have a much better building than most private office buildings in the area.

Our technical specifications have also changed over the years. Now it is much less costly than it was in the early 1980s. In 1981, we had a specification system just like that of the Army Corps of Engineers, the Naval Facilities Engineering Command, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. It was very elaborate, taking up volumes and volumes. We do not use that system any more. We were not building airfields or submarine bases. We found that a commercially based specification system was fine. Once there were a dozen people in GSA's central office writing specifications. We signed a contract with the American Institute of Architects and we bought several subscriptions to AIA's Masterspec. For a short time, we actually had a Masterspec/GSA version, but now we use the real thing. However, if the architect-engineer firm has a specification system that is based on the Construction Specifications Institute format and

is otherwise sound, that can also be used.

This is just one example of ways in which we have instituted private sector concepts. Many GSA people once agonized over every single line in design review. We no longer do this. We have construction managers do constructability review, to make sure that the documents are ready to go out for competitive bid. We are doing things much more in keeping with private industry practices. We also focus more on the implementation of important Executive Orders, like those concerned with energy and water conservation. The details, such as making sure the door swings are right, we contract for. We concentrate on the major issues—federal mandates and issues such as accessibility. The nature of our staff has changed for this reason, acting more as managers of design than as frustrated designers.

Conclusion

The major thrust of GSA's program for the next 10 to 15 years will be major adaptive reuse projects, to bring our huge inventory up to modern standards. The big question is how we will do that. Of course, the office of the future may be in your house as a result of telecommuting. We have many unknowns to face.

However, we feel that, working together with our client agencies and other government branches, we can use the methods of our design quality program—problem identification, followed by research, development, and prototypes—to move the discussion to practical solutions. We have seen these methods produce results, such as the innovative HVAC approach of the Phoenix courthouse, which was specifically cited in the Progressive Architecture Award.

We really need to look at the role of government. Government cannot do everything, and probably should do less than it does. However, architecture and art have historically reflected the values and the long-term goals of our society. I believe government can, in fact, reinforce certain values that we hold as a people. We do have a responsibility to try to highlight the positive aspirations of our people and our society. We can have a balanced budget in 10 years and have nothing but balanced books. Is the goal only a balanced checkbook, or is it also that what we have bought is of value? The civic responsibility of our professions—engineering and architecture—I believe, is a truly important calling.