1

Introduction

With what strift and pains we came into the World we know not; but 'tis commonly no easie matter to get out of it.

Sir Thomas Brown, Letter to a Friend, c. 1680

In some respects, this century's scientific and medical advances have made living easier and dying harder. On the one hand, discoveries and innovations in public health, biomedical sciences, and clinical medicine have brought remarkable advances in our abilities to prevent, detect, and treat many illnesses and injuries. Killers such as smallpox, polio, diphtheria, and cholera have vanished or been greatly curbed by advances in sanitation, nutrition, and immunization. The infections that made childbirth so dangerous are now mostly avoidable. Especially in technologically developed countries such as the United States, many families cherish children who would have been lost to prematurity in decades past. Curative and rehabilitative treatments for previously disabling injuries and deadly diseases now allow many people to resume productive and satisfying lives.

On the other hand, many people have become fearful that the combination of old age and modern medicine will inflict on them a dying that is more protracted and, in some ways, more difficult than it would have been a few decades ago. In countries such as the United States, most people now die of chronic illnesses such as heart disease and cancer. The prevalence of chronic illness and death at an advanced age challenges health care delivery, financing, research, and education systems that were designed primarily for acute illness and injury rather than for serious chronic or progressive degenerative illness. The treatments that clinicians may see as rescuing people, if only briefly, from imminent death may sometimes be experienced by patients and families as a torment from which they need to be freed. News stories periodically appear that recount a daughter's or a husband's or a

friend's grief and anger at being unable to save a loved one from being tethered to medical devices, violated by resuscitation maneuvers with little prospect of success, or maintained in the unknowable depths of catastrophic brain damage.

These news stories, even if not typical, may nonetheless significantly affect public anxieties. This is especially likely when the stories are presented in sensational or emotional terms that give the impression that poor care results from arrogance and callousness rather than from flaws in general systems of care or from uncertainties about the prognoses for gravely ill patients, the consequences of alternative treatments, the preferences of patients and families, and the applicable ethical and legal standards for care. In addition, the news and entertainment media may mislead and misinform through their frequent and persistent emphasis on violent or sudden death, death at a young age, and dramatic medical resuscitations that are, in real life, rarely successful (Baer, 1996; Diem et al., 1996). Television, in particular, is both saturated with spectacular death and largely uninterested in the everyday realities of dying as it is experienced by most people.

While an overtreated dying is feared, the opposite medical response—abandonment—is likewise frightening. Patients and those close to them may suffer physically and emotionally when physicians and nurses conclude that a patient is dying and then withdraw—passing by the hospital room on rounds, failing to follow up on the patient at home, and disregarding pain and other symptoms. Abandonment is also a societal problem when friends, neighbors, co-workers, and even family avoid people who are dying. As this report documents, the neglect of dying extends to medical curricula and research agendas that emphasize medicine's curative goals with little attention to the prevention and relief of distress and suffering for those people who, inevitably, will die of their illnesses or injuries. It is a dual perversity that interest in assisted suicide sometimes reflects anxiety about overly aggressive medical treatment, sometimes dread about abandonment, and sometimes fear that dying people may suffer simultaneously or sequentially from both misfortunes.

As will be described further in this report, the biomedical advances and health care practices that have institutionalized death and sometimes prolonged suffering and dying have not gone without notice or response by policymakers, clinicians, ethicists, and communities. For example, since the first U.S. hospice was founded in Connecticut in 1974, clinicians, patients, families, community volunteers, and policymakers have mobilized under the hospice banner to design and implement ways of reducing suffering and improving the quality of life for dying patients and those close to them. Within the health professions, the developing field of palliative medicine has helped focus biomedical and clinical research on the biological mechanisms of pain and other symptoms, the methods for assessing symptoms,

and the means of preventing and relieving physical, psychological, and spiritual distress.

In the policy arena, by establishing limited Medicare coverage for hospice care, the government acknowledged the special needs of dying patients and those close to them. Legislators and judges have also attempted to give patients and their families more control over the way death occurs through policies that require informed consent to treatment, encourage planning in anticipation of death, and recognize patients' (and surrogates') right to stop medical interventions.

The time is right for further action at all levels to improve care for those approaching death and to assure the fearful that they will be neither abandoned nor maltreated. The intense debate over assisted suicide appears to be increasing public recognition of deficits in end-of-life care and consolidating agreement among proponents and opponents alike that people should not view suicide as their best option because they lack effective and compassionate care as they die.1 As discussed further below, a small but growing number of initiatives are beginning to tackle a wide array of health care and other deficiencies that contribute to poor care at the end of life. In addition, a number of widely publicized books and stories have portrayed dying and death in ways that are realistic and positive but also sensitive to popular fears and concerns. On a more personal level, news reports on public figures such as Richard Nixon, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, and Joseph Cardinal Bernardin have portrayed older people with incurable illnesses preparing for and meeting death with grace and courage.

The goals of this Institute of Medicine (IOM) report are to extend understanding of what constitutes good care at the end of life and to promote a wider societal commitment to create and sustain systems of care that people can count on for spiritual, emotional, and other comfort as they die. More specifically, it is intended to stimulate health professionals and managers, researchers, policymakers, funders of health care, and the public at large to develop more constructive perspectives on dying and death and to change practices, policies, and attitudes that contribute to distress and suffering at the end of life.

This report focuses on health care-related aspects of dying including clinical and supportive services, financing of such services, and professional education. These are, of course, only a part—often a minor part—of the dying process as experienced by patients and those close to them. The support of family and friends, religious congregations, workplaces, and

|

1 |

While this report was being prepared, two cases involving assisted suicide were argued before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court ruled on June 30, 1997 (after this report was publicly released) that there is no general constitutional right to physician assistance in suicide. See Chapter 7 for further discussion. |

other parts of the community may be more significant and more meaningful to many, if not most, of those approaching death.

The Need for Consensus and Action

The need for consensus and action to improve care for those approaching death is growing more urgent. Part of this urgency stems from demographic and social trends, including the nation's aging population, changing family structure, and growing ethnic and religious diversity. In addition, efforts to control health care costs and reduce government spending are putting pressure on Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security programs that are especially important to those with serious chronic and advanced illnesses. These changes and developments can impose serious stress on those providing medical care, who often feel trapped by conflicting demands—from patients, families, colleagues, health care purchasers, health plan managers and stock owners, and government officials—for compassion, economy, and conformity with professional and legal standards of practice.

Care for dying patients is, in considerable measure, publicly funded, because almost three-quarters of those who die each year are age 65 or over and are covered by Medicare and, to a lesser extent, by the federal-state Medicaid program. Medicare and Medicaid also cover many younger people, for example, young adults and children dying of AIDS. In addition, care for some among the dying may be covered by programs for veterans, military personnel, and homeless people or others who lack public or private insurance. For those approaching death, therefore, government policies play a major role in determining what health care and related services are covered, how health care practitioners and institutions (including health plans) are paid, and how those serving beneficiaries are to be held accountable for the quality, cost, and accessibility of care. In addition, federal and state laws govern many other aspects of health care, including consent for services and protection from racial and other discrimination. Thus, improving care at the end of life requires supportive federal and state policies, including financing policies.

Efforts by public and private purchasers of health care to control costs have emphasized what is popularly described as managed care. As discussed further in Chapters 4 and 6, managed care has a variety of dimensions and meanings, which users of the term often do not specify precisely and which listeners may perceive in ways quite different from what the user had in mind. In process terms, managed care may refer to any one or a combination of several financial, organizational, legal, educational, or other techniques intended to influence whether, how, or from whom patients receive preventive, diagnostic, therapeutic, or other services. In organizational terms, managed care may refer to an entity that employs these tech-

niques in one of several different formats. Beyond a general agreement that cost control has been the driving force behind the surge in managed care, health policy analysts and researchers disagree on what specific processes and formats should qualify for the managed care label.

One idealistic view of managed care (most often associated with cohesive, integrated health plans such as well-established, staff- or group-model health maintenance organizations) is that it will do more than traditional fee-for-service medicine to limit costs and to serve other valuable goals. These goals include preventing illness, encouraging patient responsibility, diminishing inappropriate treatment, improving continuity of care, coordinating care through primary care teams rather than relying on a collection of independent specialists, and making available services not traditionally covered by health insurance. If "preventing pain and other distressing symptoms" is substituted for "preventing illness" in the above description of managed care, then this idealistic image mirrors in many respects the ideal described above for the hospice movement and the field of palliative care.

Unfortunately, market competition, rapid growth, and continuing pressure to control costs and increase profits may encourage practices by some health plans and organizations that are seriously at odds with the ideal image of managed care. Such practices may include undertreating illnesses and symptoms, discouraging new or continued enrollment by sicker individuals, and failing to make timely referrals for specialized care. Both fee-for-service and managed care appear to fall short in rewarding care that ensures meticulous symptom evaluation and reevaluation, services and settings appropriate to patient needs, coordination of services, and counseling paced to what people can absorb and tolerate. Later chapters of this report explore these issues in more depth.

Initiatives to Improve Care at the End of Life

Since this study was originally conceived, several promising collaborative initiatives have gotten under way to improve the quality, accessibility, and affordability of care for dying patients and those close to them. The focus and scope of these initiatives is quite varied. Some involve one or more institutions within the same community whereas others extend to whole states; some are national in scope. Funding comes from diverse internal and external sources including government agencies and several private foundations such as the Open Society Institute's Project on Death in America, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Commonwealth Fund, the Greenwall Foundation, the Culpeper Foundation, and the Milbank Memorial Fund. A grantmakers group including these and other organizations is also meeting to encourage knowledge sharing, coordination, and identification of neglected issues.

The leaders in these initiatives range from community hospitals and hospices to regional health care systems to national organizations such as the American Medical Association and the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Health Care Organizations. Objectives are likewise varied as illustrated below and in later chapters and Appendix C.

In Missoula, Montana, a broad coalition of community leaders and health care providers is undertaking a community-wide demonstration project to examine and improve the care and support available to dying people and those close to them (MDP, 1996). The effort crosses the spectrum of services and settings—including emergency medical services, long-term care, hospice, hospital, and home care. The initiative includes a research component as well as the demonstration aspect.

Across the country in New York City, the United Hospital Fund has organized a three-year, 12-hospital project that will investigate how care is delivered to dying patients and test innovative palliative care programs (UHF, 1997). Hospitals receiving planning grants from the Fund will review care patterns for common fatal illnesses, use focus groups of survivors to assess satisfaction with care, survey hospitals to assess the availability of palliative care services, and convene focus groups of health care professionals to assess their knowledge and attitudes. Follow-up grants for selected hospitals will support the implementation and evaluation of new palliative care strategies.

Supportive Care of the Dying: A Coalition for Compassionate Care involves six Catholic health care organizations around the nation in work to promote appropriate and compassionate care for people with life-threatening illness, and their families (Super, 1996). The coalition coordinates efforts to develop and test care models, practice guidelines, leadership and skills, and educational and mentoring programs in health systems. One stimulus for the coalition was Oregon voters' approval of physician-assisted suicide in 1994, which demonstrated public concern about how modern medicine cares for the dying. An important element of the initiative is the convening of 50 focus groups around the nation to develop a better understanding of people's needs and expectations.

The Oregon vote (which was under judicial challenge while this report was being drafted) also prompted other efforts within that state to improve care at the end of life (Lee and Tolle, 1996). The Oregon Health Sciences University, for example, has helped organize hospitals, nursing homes, emergency medical personnel, state regulators, and others in a statewide effort to create practical, reliable procedures for seeing that patient preferences about end-of-life care are known and honored.

Researchers at George Washington University have organized a Center to Improve Care of the Dying. They have, among other projects, been working to improve the definition and measurement of outcomes relevant

to people approaching death and those caring for them and to develop ways for managers and clinicians to use outcomes measures to improve care in hospices, nursing homes, and other settings (see Appendix E).

Improved end-of-life care has also been identified as a topic for the Breakthrough Series of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). This activity uses intensive training and rapid cycles of innovation and evaluation to achieve so-called "breakthrough" improvements in participating programs. Projects have ranged from patient waiting times (e.g., for surgery, emergency treatment, office visits) to cesarean section rates (IHI, 1997). The series on care at the end of life will focus on pain management and palliative care, advance care planning, transfers among care settings, and family support.

Recognizing the deficits in the knowledge and practice of established physicians in caring for dying patients and those close to them, the American Medical Association has begun a comprehensive, collaborative educational strategy directed at established clinicians (American Medical News, 1997). It has solicited participation and information from a broad range of organizations, such as the American Board of Internal Medicine, the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, the Picker Institute, the Supportive Care of the Dying Coalition, and many others. A major element of this initiative is a program to train initial groups of physicians who will then return to their communities to teach others. Various other projects are also seeking to redesign undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education in the health professions to help clinicians do better throughout their careers in recognizing, respecting, and meeting the needs of those they cannot cure.

Some organizations, including private foundations are attempting to enlist the mass media in public education about the nature of dying and the ways people can be helped to have a death free from avoidable distress and consistent with their wishes. Journalists, television producers, and others involved in mass communications are also being encouraged to present a less skewed portrayal of death with less emphasis on heroic but implausible resuscitations and violent but impersonal deaths that have few lasting effects on survivors.

A few initiatives are designed to shape Medicare policies related to care of those with serious and eventually fatal illnesses. One, for example, would direct the Health Care Financing Administration to undertake a demonstration and evaluation program in coordinated end-of-life care that would test a range of innovations and focus on capitated models of care (Lynn, 1996b). Others would change how hospice eligibility is determined. In addition, one initiative would require the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to report to Congress annually on the state of affairs regarding care at the end of life.

Overview of Report

The origins, approach, and purposes of this study are described in the Preface and in the report of a small group that planned this study (IOM, 1994a). The Institute of Medicine committee appointed to undertake the study prepared this report with the objectives of stimulating discussion, encouraging consensus on how care for those approaching death can be improved, and galvanizing action to implement that consensus. The target audiences include clinicians of all kinds, professional organizations, health professions educators, state and federal policymakers, managed care executives, public and private purchasers of health care, certifying and accrediting groups, organizations representing patients and families, and the public at large. This document, which was reviewed in accordance with the procedures required by the National Research Council, constitutes the final report of the committee. The nine following chapters examine

- the way people die—when, why, where, and how (Chapter 2);

- the elements of good care at the end of life (Chapter 3);

- the factors that make it easier or harder to care well for those who are dying including organizational structures and procedures (Chapter 4), quality assessment and improvement strategies (Chapter 5), financing arrangements (Chapter 6), laws (Chapter 7), and health professions educational programs (Chapter 8);

- the role that biomedical, health services, and other research can play in creating a stronger knowledge base for good end-of-life care (Chapter 9); and

- the steps that clinicians, policymakers, health care administrators, and others can take to correct deficiencies, improve performance, and generally help people have a better dying (Chapter 10).

Because health care and supportive systems are so closely connected to local and national policies, structures, and practices, the focus here is on the United States. Nonetheless, the committee tried to learn from the experience of other countries and to develop a report that would be useful beyond this nation's boundaries.

The committee also recognized that uncertainties and disagreements about appropriate care for those with life-threatening medical problems often focus on those at the extremes of life's range—the very young and the very old. The clinical situations characterizing these groups may also represent extreme points—catastrophic physiological deficits for the neonate and long-term deterioration and multiple organ failure for the very old person. Difficult decisions and troubling questions about care for those approaching death are not, however, limited to certain age groups, clinical

problems, settings of care, treatment strategies, or decisionmakers (e.g., health professionals, patients, or families).

Because most of those who die are older adults, the discussion emphasizes but is not restricted to this group. Moreover, regardless of age, the process of dying varies considerably across individuals, even for individuals with the same diagnosis. The implications of this variation for the care of dying patients—including adults and children, mentally competent and otherwise, severely symptomatic and relatively comfortable—are considered throughout this report.

Guiding Principles

As the study committee discussed its charge and its approach, it recognized that it was being guided—sometimes explicitly, sometimes implicitly—by a set of working principles. Most reflect a combination of value statements and empirical assumptions. Below are some of the key precepts, and others are identified later in the report. Only the first of the following principles applies exclusively to care at the end of life.

Care for those approaching death is an integral and important part of health care. Everyone dies, and those at this last stage of life deserve attention that is as thorough, active, and conscientious as that provided to those for whom disease prevention, diagnosis, cure, or rehabilitation are still dominant goals. Individual and system failures to care humanely for dying patients—including failures to use existing knowledge to prevent and relieve distress—should be viewed as clinical and ethical failures.

Care for those approaching death should involve and respect both patients and those close to them. As for all patients, clinicians need to consider dying patients in the context of their families and close relationships and be sensitive to their culture, values, resources, and other characteristics. Although this report often refers to patients and those close to them, it also uses the term family in a general sense to include not only the traditional family (e.g., spouse, children, parents, siblings) but also others such as lovers, friends, and godparents who are significant and close to patients in an emotional, spiritual, or sometimes fiduciary sense.

Good care at the end of life depends on clinicians with strong interpersonal skills, clinical knowledge, technical proficiency, and respect for individuals, and it should be informed by scientific evidence, values, and personal and professional experience. Clinical excellence is important because the frail condition of dying patients leaves little margin to rectify errors. Scientific and clinical knowledge are important, but so are compassion, communication skills, experience, and thoughtful reflection on the meaning of that experience.

The health care community has special responsibility for educating

itself and others about the identification, management, and discussion of the last phase of fatal medical problems. The "medical model" often acknowledges inadequately the emotional and spiritual aspects of life's ending. Still, dying is also a biological process that can be—in varying degrees depending on the circumstances—managed by teams of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, therapists, and others prepared to relieve distress, offer information and guidance, and provide support to dying patients and those close to them. Physicians and often nurses judge when death is imminent and thus signal that people should prepare for it, and for most people, physicians legally certify death. Given their central, if not always adequately performed, roles in care at the end of life, health care professionals are inescapably responsible for educating themselves and the broader community about good care for dying patients and their families.

More and better research is needed to increase our understanding of clinical, cultural, organizational, and other practices or perspectives that can improve care for those approaching death. The committee began—and concluded—its deliberations with the view that the knowledge base for good end-of-life care has enormous gaps and is neglected in design and funding of biomedical, clinical, psychosocial, and health services research. Such research is, however, particularly sensitive and in need of more than additional resources and data. Asking the right questions and answering them in ethically acceptable ways are critical.

Changing individual behavior is difficult, but changing a culture or an organization is potentially a greater challenge—and often is a precondition for individual change. Powerful statements about the importance of compassionate care, effective symptom management, advance planning, and similar matters are not enough to improve care of the dying. Making values and policies work organizationally, financially, politically, legally, and otherwise requires a combination of good practical judgment by policymakers and good mechanisms to hold organizations responsible for their performance.

Concepts and Definitions

During its work, the committee considered how it would define several key concepts, many of which are loaded with emotional and moral meanings and marked by disagreements. The discussion below covers some of these concepts, including those of "bad" and "good" deaths. Other concepts such as accountability, advance care planning, and managed care are defined elsewhere in the report. In general, the committee found that the "language of dying" was neither as clear nor as specific as it might usefully be. The discussion below attempts to clarify some concepts, but the com-

mittee does not suggest that the experience and meaning of dying can be reduced to a glossary of terms.

Good and Bad Deaths

Because notions of bad and good deaths are threaded throughout discussions about dying and death, some consideration of their meanings is appropriate—with the caveat that the concepts are not fixed in meaning but rather shaped by people's personal experiences, spiritual beliefs, and cultural backgrounds. The concepts are also somewhat fluid in response to changes in social mores, technology, and options for dying.

In reflecting upon members' professional and personal experiences, the committee suggested that a decent or good death is one that is: free from avoidable distress and suffering for patients, families, and caregivers; in general accord with patients' and families' wishes; and reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural, and ethical standards. A bad death, in turn, is characterized by needless suffering, dishonoring of patient or family wishes or values, and a sense among participants or observers that norms of decency have been offended. Bad deaths include those resulting from or accompanied by neglect, violence, or unwanted and senseless medical treatments.

Some would add other elements to the characteristics of a good death, for example, that it comes with reasonable warning, occurs in the company of loved ones, and provides the opportunity for people to reconcile with families and friends and achieve the kind of meaning, peace, or transcendence that is relevant and significant for them and those close to them (Gavrin and Chapman, 1995; Samarel, 1995; Jennings, 1996; Byock, 1997a, 1997b). Some people, however, clearly view sudden death as preferable, even if it deprives them of the chance to resolve their lives with meaning, to say goodbye to loved ones, and to settle financial and legal matters.

Further, although the more expansive vision of a good death is intended to encourage a sensitive regard for dying patients and a more positive view of how life can be lived in the face of death, such a vision also carries some potential risks. It may expose some patients and families to feelings of guilt and anger because conflicts were not resolved or reconciliations achieved or spiritual serenity reached. It may also reflect values of the dominant culture that are not shared by all, and it may induce some naive caregivers to try subtly or not so subtly to impose their values on dying patients and families. A humane care system is one that people can trust to serve them well as they die, even if their needs and beliefs call for departures from routine practices or idealized expectations of caregivers.

Another concept, that of a dignified death, also presents some perplexing questions (see, e.g., the introductory discussion in Nuland, 1994; also,

Madan, 1992; Quill, 1993, 1995; Byock, 1997b; Hennezel, 1997). To those who particularly stress autonomy, the phrase death with dignity has become a shorthand way to refer to laws and practices that "permit a competent terminally ill adult the right to request and receive physician aid-in-dying under carefully defined circumstances" (Humphrey, 1991, p. 177). To others it may imply a dying accompanied by respectful and skillful caregiving. To still others, a dignified death may suggest a death that is largely free from dependency or physiological affronts that are not usually perceived as dignified. Such affronts, which even superlative patient care may not always prevent, include pain, incontinence, vomiting, delirium, or traumatic but sometimes appropriate medical interventions. Given this conflict with the everyday meaning of dignity, the concept of a dignified death may unwittingly romanticize death, and its incautious use may produce distress or anger by creating expectations that professional and other caregivers cannot always fulfill for all patients, given the nature of their disease. A worthy and more achievable goal is death dignified by care that honors and protects—indeed cherishes—those who are dying, that conveys by word and action that dignity resides in people, not physical attributes, and that helps people to preserve their integrity while coping with unavoidable physical insults and losses.

Quality of Life, Quality of Dying, Quality of Care

Most people wish for a long, satisfying life, that is, they value both how long they live and how well they live. In response, the concept of health-related quality of life has emerged to emphasize health as perceived and valued by people for themselves (or, in some cases, for those close to them) rather than as seen by experts (see, e.g., Patrick and Erickson, 1993; Cohen, Mount, et al., 1995; Gold et al., 1996). Going well beyond traditional mortality and morbidity measures, health-related quality-of-life outcomes include physical, mental, social, and role functioning; sense of well-being; freedom from bodily pain; satisfaction with health care; and an overall sense of general health.

The concept of quality of dying, which is less fully developed, focuses on a person's experience of living while terminally ill or imminently dying (Wallston et al., 1988). It, too, focuses on outcomes broadly defined, but does so within the special world of the dying patient, for whom some physical outcomes become less realistic while other outcomes (e.g., spiritual well-being or sense of peace) may become more meaningful.

Quality of care stresses the link between the structure and processes of health care and outcomes for individuals and populations. High-quality care should contribute to the quality of living and the quality of dying but is not synonymous with them. Chapter 5 considers these concepts further.

Pain, Symptoms, and Suffering

Pain and suffering are terms that are often used interchangeably, but it is worth distinguishing between the two. Physical pain may be defined as "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage, or both" (International Association for the Study of Pain, 1979). This experience may include a range of physical and mental sensations (e.g., aching, burning, numbness, tightness) that vary in severity, persistence, source, and management. For pain and many other symptoms, assessment depends largely on patients' reports rather than on laboratory or other test results. Although some symptoms (e.g., vomiting, incontinence) are observable, patients' reports on their level of distress—how much the symptoms bother them—are still essential.

Suffering is a more expansive concept than pain. It goes beyond unpleasant sensations or distressing symptoms to encompass the anguish, terror, and hopelessness that dying patients may experience. A dying person who experiences few if any physical symptoms may suffer greatly if he or she feels that life has lost any meaning.

Cassell has suggested that a symptom or feeling becomes suffering when people perceive it as a "threat to their continued existence—not merely to their lives but their integrity as persons" (Cassell, 1991, p. 36). Such perceptions may have significant emotional and spiritual dimensions related to self-image, family relationships, past experiences, caregiver attitudes, and other circumstances of a patient's life (Byock, 1997a). Perceived helplessness and exhaustion of coping resources are key elements of suffering (Gavrin and Chapman, 1995). Ultimately, however, suffering is "a personal matter—something whose presence and extent can only be known to the sufferer" but which cannot be ignored (Cassell, 1991, p. 35).

The concept and meaning of suffering has a prominent and revered position in many religions and philosophies. The committee recognized that some people may esteem suffering and even reject efforts to alleviate the physical symptoms that may contribute to suffering. It believes, however, that those caring for dying patients have a responsibility, first, to explain to people that pain and other distress can often be relieved and, second, to consider whether the patient would benefit from an exploration with a chaplain or other counselor of the nature and significance of suffering.

The End of Life, Dying, and Death

What is meant by "the end of life?" This phrase as used in this report does not imply only old age or the concluding phase of a normal life span, although that is one common meaning of the phrase and is the focus of much of this report. Life's ending can come at any age and time, and death

at a young age is a special sorrow. Although people can, in some respects, be considered to be approaching death from the moment they are born, the committee used the phrase approaching death partly to be more explicit and partly to take advantage of the idea that death is approached not just by those who are dying but—with varying degrees of intimacy and openness—by families, friends, caregivers, and communities.

In one formulation, "people are considered to be dying when they have progressive illness that is expected to end in death and for which there is no treatment that can substantially alter the outcome" (AGS, 1997). Dying, however, is not a precise descriptive or diagnostic term (Pollack et al., 1994; Thibault, 1994; Lynn et al., 1996). It was the committee's sense that those referred to as dying are often thought to be likely to die within a few days to several months but that those described as having an incurable, terminal, or fatal illness also include people with advanced progressive illnesses whose deaths are less predictable and might not come for years. This report tends to focus on those expected to die within days or months; much of the discussion also applies to care for all those with life-threatening illness.

The definition of death was not itself a central concern of the committee, because many—probably most—significant decisions about care for dying individuals do not hinge on precise determinations of death. Nonetheless, the committee recognized the uneasiness and controversies created by technologies that make possible the "artificial" prolongation of cardiac and respiratory functions (the traditional markers of life) long after cognition and consciousness and other brain functions are irretrievably lost. Likewise, the committee recognized that some people may fear being declared dead prematurely and that trust in those providing care at the end of life may be compromised by controversies about modifying the determination of death to expand the availability of organs for transplantation. Scientists, philosophers, clinicians, theologians, policymakers, and others have sought a scientific, moral, and political consensus on when death can be declared. Most rely on some conception of brain death.2

By not examining the issues in defining death, the committee did not discount the importance of continued efforts to understand the physical processes of death, to develop scientifically based and socially acceptable criteria that are feasible to use in declaring death, and to design processes that support clinicians in properly applying the criteria.3 The committee did not, however, want such efforts and the controversies surrounding them to distract attention from the much more common deficiencies in care for those approaching death and from strategies that would improve end-of-life care.

The Trajectory of Dying

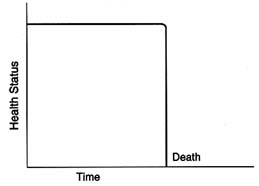

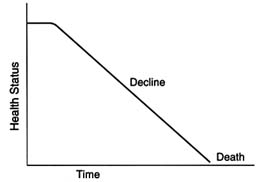

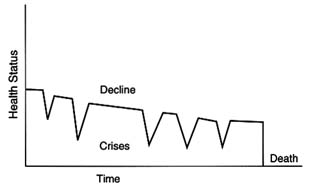

The concept of a trajectory of dying has been used to illuminate similarities and differences in patient experiences as they approach death (Glaser and Strauss, 1965, 1968; Pattison, 1977; McCormick and Conley, 1995). As described by Glaser and Strauss, "the dying trajectory of each patient has at least two outstanding [and variable] properties…duration and shape" (p. 6). Figure 1.1 offers greatly simplified examples of three possible trajectories toward death.

Some people die suddenly and unexpectedly (Figure 1.1A); others have forewarning. Those who die suddenly, for example, in an accident or of a massive heart attack, are not the focus here, although support for bereaved survivors is an important role for clinicians and others. Among those with forewarning of death, some may steadily and fairly predictably decline, as many cancer patients do (Figure 1.1B). Other people may have fairly long periods of chronic illness punctuated by crises, one of which may prove fatal—although an entirely different problem may intervene to cause death (Figure 1.1C). These patients may understand that they have a progressive disease that will likely kill them, but they nonetheless may not see themselves—or be seen by their families and friends—as dying.

Those with forewarning of death may be further differentiated between those thought to be imminently dying (i.e., likely to die within minutes to days) and those who are terminally ill but not thought to be "actively" dying (i.e., having a life expectancy of days to months, sometimes years). This latter group may have a period of "chronic living-dying" between diagnosis of an incurable illness and imminent death (McCormick and Conley, 1995). During this period, people may continue many ordinary activities of daily life while coping with the prospect of death and preparing

for it. Many pediatric patients, for example, spend years—and with better treatments, even decades—with illnesses such as cystic fibrosis, complex congenital malformations, and neurodegenerative disorders. Although families hope for a cure to emerge from scientific research, premature death (i.e., less than normal life expectancy) is a likely prospect. It may occur suddenly, for example, from a superimposed viral illness, or it may come after an extended but clearly evident physical decline. Chapters 3 and 4 further consider variations in the dying process and the implications for care at the end of life.

Diagnosis and Prognosis

The diagnosis of incurable, progressive disease that is expected to prove fatal is among the most difficult and sobering judgments that physicians make. Such a determination generally signals the need for patients, families, and clinicians to reconsider clinical and personal priorities. It is also currently important because Medicare coverage for hospice services, which are designed specifically for dying patients, requires a determination that a beneficiary has a terminal illness and, perhaps more intellectually daunting, has a life expectancy of six months or less.

Moving from a clinical diagnosis of a terminal or incurable illness expected to end in death to a prognosis—a prediction of the course of the illness and remaining life expectancy—is an exercise in uncertainty. (See Appendix D and Chapter 3 for further discussion.) One approach to prognosis uses explicit clinical criteria and formulas to generate a calculated probability that a person will live some defined period of time (e.g., a 50 percent probability of living six months) (McClish and Powell, 1989; Lynn et al., 1996). Even very near the actual time of death, however, prognosis is often imprecise. Some will die more quickly than expected; others will die more slowly.

Uncertainty about prognosis and methods for establishing it may have significant policy as well as personal implications. For example, "the Medicare hospice benefit, notably, manages to give a date" but not an expected rate or probability of surviving for six months (Lynn et al., 1996, p. 315). When insurance or other benefits are contingent on the accuracy of prognoses, physicians' judgments may be reviewed or even "audited" by hospice personnel or government officials who may not understand the uncertainty inherent in projecting survival. (See Chapter 6.)

Hospice and Palliative Care

As will be discussed throughout this report, hospice and palliative care are responses to perceived inadequacies in the prevention and relief of

symptoms and distress in people approaching death. The term hospice has at least three somewhat different uses that can be confusing and even misleading. First, a hospice may be a discrete site of care in the form of an inpatient hospital or nursing home unit or a freestanding facility. Most care for hospice patients in the United States is, however, provided in the home by family members. Second, a hospice may be an organization or program that provides, arranges, and advises on a wide range of medical and supportive services for dying patients and their families and friends. This meaning is most common in this report. For example, when patients are described as entering hospice care, it means they are affiliating with a hospice program (and, often, qualifying for insurance coverage for care provided by such a program). Less than 20 percent of those who die in the United States are enrolled in hospice programs. The third and most culturally sweeping meaning of hospice encompasses an approach to care for dying patients based on clinical, social, and metaphysical or spiritual principles.

When this report refers to an approach to care rather than to hospice programs or organizations, it generally uses the term palliative care. In a broad sense, palliative care seeks to prevent, relieve, reduce, or soothe the symptoms of disease or disorder without effecting a cure (see, e.g., Random House Dictionary, 1983; American Heritage Dictionary, 1992; Stedman's Medical Dictionary, 1995.)4 Palliative care in this broad sense is not restricted to those who are dying or those enrolled in hospice programs. For example, palliation of symptoms may be an important adjunct to life-prolonging therapies, both because the prevention or relief of pain and other symptoms is important for a patient's quality of life and because it may also allow people to begin and complete difficult treatment regimens that they might otherwise not tolerate or follow successfully (MacDonald, 1991). Palliative care, broadly conceived, is also important to those who live with chronic pain or other symptoms.

As an area of academic, scientific, and clinical specialization or empha-

sis, the field of palliative medicine focuses on patients with life-threatening medical problems for which cure is not seen as possible.5,6 Instead, it focuses on the prevention and relief of suffering through the meticulous management of symptoms from the early through the final stages of an illness; it attends closely to the emotional, spiritual, and practical needs and goals of patients and those close to them. These goals underscore two important realities: first, that a lot more happens to most dying people than the specific event of their death and, second, that helping people live well while dying requires sophisticated strategies and tools for measuring and monitoring symptoms, functional status, emotional well-being, and burdens associated with terminal illness and treatment. Thus, good palliative care is more than symptom management or management of patients with cancer, although both figure prominently in its practice. A fuller description of the dimensions of palliative care is presented in Chapters 3 and 4.

Conclusion

This IOM study arose in an environment of growing awareness of deficiencies in care at the end of life and growing conviction that steps to improve care were essential. In the years since the study was first contemplated, the environment seems to have become more favorable to positive change and more open to discussion of the dying process. Even the contentious and often bitter debate over the legality or morality of physician-assisted suicide has had positive benefits in forging agreement that deficiencies in care for dying patients may contribute to demands for assisted suicide and that such deficiencies need to be remedied.

When he was approaching death, Joseph Cardinal Bernadin reflected, "As you enter the dying process, that process prepares you for death as you slow down…So when I talk about being at peace, I'm talking not only about peace at the level of faith, but also humanly speaking. Before too long, I'm going to go, and I think I will be ready for it" (Bernardin, 1996, p. 115). Communities, too, need to be ready, that is, prepared to support people through the dying process. The rest of this report examines how individual and collective changes in attitudes, knowledge, policies, and practices can create and sustain such readiness.