E Cultural Diversity in Decisionmaking About Care at the End of Life

Barbara A. Koenig, Ph.D.*

Introduction

The overall goal of this IOM panel is to examine the questions: "What medical care is appropriate at the end of life? Who should decide?" My specific task is to locate these questions within the context of an increasingly diverse U.S. population. This view will of necessity be a fleeting one, providing images of this important terrain from an altitude of 10,000 feet; a quick flyover of issues better studied in-depth at ground level. A detailed examination of the hills and valleys inhabited by Americans from diverse cultural backgrounds is certainly needed; research is currently scant. An IOM study of dying, decisionmaking, and care at the end of life will need to avoid the many obstacles and pitfalls looming in this landscape. Most of the obstacles are camouflaged, hidden in our common sense assumptions about race, ethnicity, and cultural difference and in unexamined assumptions at the core of current bioethics practice. The goal of this paper is to provide a set of signposts for navigating through this terrain. I argue that these signposts are ultimately of more value than an approach that generates a list of "traits" specific to each ethnic group in the United States.

First, I will very briefly discuss how culture is relevant to health care,

|

* |

Paper prepared by Barbara A. Koenig, Ph.D., Senior Research Scholar and Executive Director, Center for Biomedical Ethics, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California. Prepared for the Institute of Medicine Committee for the Feasibility Study on Care at the End of Life. (See Appendix A of this report.) |

for the issues surrounding death are but one subset of the general problem of how to take account of culture in the health care system. Next, I will review the key issue of how we talk about and understand cultural difference. What are these categories into which we divide our pluralistic society? I will next address the way in which existing bioethics practices surrounding death have failed to consider cultural difference. The latter topic is the focus of my current research. Using the methodological strategies of medical anthropology, I am studying how California patients from different cultural backgrounds make end-of-life decisions.1 Implications of cultural diversity on individual decisionmaking and resource allocation will be discussed very briefly. The paper will conclude with recommendations for the IOM panel regarding research, clinical practice, and teaching about cultural diversity and end-of-life decisionmaking.

Although beyond the scope of this brief paper, it is vital to remember that culture is not simply an inconvenient barrier to a rational, scientifically based health care system or a feature of ethnic "others." Deeply embedded cultural values are apparent in the way American medicine has approached the care of the dying, particularly practices that have separated terminal care from mainstream practice, denied the existence of the dying patient, and assumed that death was simply one of many medical problems open to a technological solution (see Callahan, 1993; Muller and Koenig, 1988). Professionals can be usefully thought of as operating within a culture influenced by widespread cultural assumptions and practices as well as by training and experience. There also appears to be a clear line dividing the medical model from the patient's model of death and illness leading to death (Churchill, 1979). And differences in professional culture between nurses and physicians may lead to varying understandings of patients' prognoses, as Anspach has demonstrated for the neonatal intensive care unit (1987). Western European health professionals respond with astonishment when told about the American practice of requiring a "Do Not Resuscitate" order for an elderly person dying in a long-term care facility. Cultural "points of view," based on specific contexts of meaning, do not apply only to patients and families from backgrounds unfamiliar to their health care providers.

In an increasingly plural society, cultural diversity among American health care workers is another important consideration. It would be inappropriate to structure the debate as if providers uniformly express white middle-class culture in opposition to the "ethnic otherness" of patients. Particularly in large urban areas, the diversity of professionals and staff workers in hospitals, nursing homes and long-term care facilities is adding a major area of complexity to decisionmaking about tube feeding, treatment of acute illness, and withdrawal of therapeutic interventions (CAHA, 1993). Many health workers providing direct patient care do not share the

assumptions on which current decisionmaking practices are based, such as the importance of respecting patient autonomy.2

Culture, Illness, and Death

Cultural analysis that reveals patients' understandings of health, illness, suffering, and death is a major concern of medical anthropology (Helman, 1990). Although "culturally sensitive" care has become a politically correct buzzword in health care recently, the use of the culture concept is often remarkably naive. Culture is often treated as a barrier to providing scientific medical care to diverse patients. Rather than recognizing the centrality of culture, "A barely hidden desire to create a 'shopping list' of cultural characteristics is sometimes discernible: Tamils do this, the Cree do that and Guatemalans do the other, in order to systematize and 'tidy up' culture in the same way as are other epidemiologic variables, such as smoking, age, gender, or fertility rates" (Lock, 1993b; p. 139). Culture is to be "overcome" in order to obtain patient compliance.

Most fully developed within the discipline of anthropology, the concept of culture is enormously complex; a full review of definitions is impossible within the scope of this paper. Emphasizing what culture is not is easier and more relevant to the goals of the IOM workshop. It is not a simple "trait," an objective, unchanging variable, located within the individual. Culture does not "determine" behavior under certain specified circumstances. Most importantly, culture is constantly re-created and negotiated within specific social and historical contexts. "Culture is now viewed not merely as a fixed, top-down organization of experience by the symbolic apparatuses of language, aesthetic preference, and mythology; it is also "realized" from the bottom-up in the everyday negotiation of the social world, including the rhythms and processes of interpersonal interactions" (Kleinman and Kleinman, 1991). Seemingly simple (and perhaps simple-minded) calls for "culturally competent care" ignore the dynamic nature of culture. Moreover, in a complex postmodern world, culture can no longer be simply mapped onto geographically isolated ethnic groups (Gupta and Ferguson, 1992). One cannot assume that a patient or family from Southern China will approach decisions about death in a certain culturally specified fashion.

Keeping in mind the warning that culture should not be considered as a simple "predictor" of behavior, it is nonetheless useful to consider how cultural analysis is critical to a full understanding of decisionmaking at life's end. Understandings of how death and the dying process are integrated into the experience of living are useful and can only be obtained by studying actual social processes (see Scheper-Hughes, 1992). Cultural conceptions of the self and personhood, the location of the individual within a

social group such as the family, orientation to the future, openness about discussing death, and ideas about what constitutes appropriate behavior by healers are all directly relevant to end-of-life decisions.

In the classic study Death and Ethnicity, Kalish and Reynolds document that "ethnic variation is an important factor in attitudes, feelings, beliefs, and expectations that people have regarding death, dying, and bereavement" (1976, p. 49). However, the relationship is not a simple one. The authors continue, "At the same time that our data show substantial ethnic differences, we are also aware that individual differences within ethnic groups are at least as great as, and often much greater than, differences between ethnic groups" (p. 49). Most studies of ethnic difference do not question the assumptions underlying comparisons of this sort. However, a closer look reveals significant hazards in traditional comparative approaches to studying cultural difference.

Thinking About Categories: Race and Ethnicity in the U.S. Health System

One justification for considering cultural diversity in decisionmaking at the end of life is the enormous demographic change that is transforming the United States. Questions such as "who controls the dying process, what is beneficial treatment for the dying, and how will individuals respond to outcomes data about prognosis?" are being asked within a society that many argue is moving swiftly toward cultural pluralism. Simplistic models of acculturation and assimilation (based on and most applicable to European immigration) have been long abandoned by both historians and social scientists (Glazer and Moynihan, 1963; Lamphere, 1992). In Table E-1, the

TABLE E-1 U.S. Population 1990 and Percentage Change, 1980-1990

|

Population Group |

U.S. 1990 |

Change from 1980 |

|

African American |

12% |

13% |

|

Asian and Pacific Islander |

3 |

108 |

|

Hispanic origin |

9 |

53 |

|

Native American |

1 |

38 |

|

White |

83 |

6 |

|

All other |

4 |

45 |

|

Total |

100 |

10 |

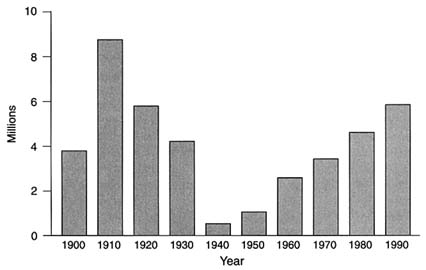

FIGURE E-1 Total immigration to the United States, by decade.

first column presents a summary of U.S. ethnic diversity as of the 1990 census; the second column shows the increase in diversity in U.S. population groups in the 10 years between 1980 and 1990 (Barker, 1992). Figure E-1 demonstrates the increase in (legal) immigration to the United States during this century.3 In terms of absolute numbers, total immigration will soon equal that of the first decades of the twentieth century; a wave of immigration that fundamentally transformed American society. Bear in mind that the social changes caused by diversity are not uniformly distributed throughout the United States; in 1988, 46 percent of refugees were received by California (Barker, 1992). In many urban and rural counties in California fully one-third of residents are foreign-born, compared with 8 percent nationally (1990 census). However, the salience of cultural diversity is not simply a response to changing demographics. The issues are intricate, deeply political, and have relevance well beyond the realm of health.4 Debates about appropriate care at the end of life will inevitably become entangled with political struggles about how to recognize "minority" voices in U.S. society.

At first glance, the categories into which we divide ourselves in American society seem self-evident and a feature of nature. In reality, these categories are highly contested politically, changing at least every 10 years when the debate about who "counts" emerges as a new census is planned. The U.S. census categories used to generate the data presented above are the end result of a political debate (featuring arguments about how to count

Hispanic people), which led to Office of Management and Budget Directive 15. This directive regulates the categories used in all federal statistics, including health statistics (OMB, 1978).

Without denying the existence of meaningful differences among groups, it is useful to consider the anthropological view that differences among people are primarily social constructs. Indeed, the traditional distinction between race and ethnicity is based on the notion that biological diversity is not salient in discussing differences among groups; ethnicity or ethnic identity is defined in terms of cultural variation. This was a major change over nineteenth and early twentieth century conceptions of race (or biological variation) as the bedrock of difference. Although the word race remains in popular use, there is general agreement that as a scientific classification it is based on outmoded concepts and dubious assumptions about genetic difference" (Barker, 1992, p. 248; see also Lock, 1993a).

Robert Hahn's empirical work with U.S. vital statistics illustrates some of the ambiguity in the way we count and define cultural difference in the United States. Table E-2 presents the results of Hahn's study, comparing the assigned race and ethnicity to U.S. infants at birth and at death one month later (Hahn et al., 1992).5 The ways in which people define themselves, or are defined by others, are inherently fluid, changing significantly over time. Any attempt to consider issues of difference must include this complexity (CDC, 1993).

The political dangers of accepting social categorization in an uncritical way are best observed by considering such categories in the context of

TABLE E-2 Inconsistencies in Coding of Race and Ethnicity Between Birth and Death in U.S. Infants

|

Population Group |

Discrepancy Birth/Death |

|

African American |

4.3% |

|

White |

1.2 |

|

Japanese |

54.1 |

|

Chinese |

47.6 |

|

Hispanic origin |

30.3 |

|

Total |

3.7 |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Hahn et al. (1992). |

|

another society. Sharp has written about the problems of categorization in South Africa.

To many South Africans it is self-evident, a matter of common sense, that the society consists of different racial and ethnic groups, each of which forms a separate community with its own culture and traditions. It is believed that such groups actually exist objectively in the real world, and that there is nothing anybody can do to change this. … We take issue with this notion, arguing that all these groups, and the bases on which they are supposedly constituted, are social and cultural constructions. They are representations, rather than features, of the real world. They comprise the ways in which a portion of South African society tries to tell itself, and others, what that world is like. In other words, they are an interpretation, instead of a mere description of reality. Any interpretation depends on the identity, beliefs, knowledge and interests of the people doing the interpreting, as much as on the characteristics of the objects being interpreted. It follows from this that different races and ethnic groups, unique cultures and traditions, do not exist in any ultimate sense in South Africa, and are real only to the extent that they are the product of a particular world view. (1988, p. 1)

Programs of research or suggestions for clinical practice that recognize cultural difference (whether defined as race or ethnicity) must be used with extreme caution (see also Sheldon and Parker, 1992; Osborne and Feit, 1992). This is particularly true in the U.S. context because of the significant overlap between categorizations based on race/ethnicity and the economic impoverishment of social class.6

Culture and New Bioethics Practices Surrounding Death

The timing and manner of death in hospitals and nursing homes are frequently negotiated, dependent on human agency (Slomka, 1992). Death and decisionmaking surrounding the event of death have been a primary focus of the evolving discipline of bioethics over the past 20 to 25 years (Callahan, 1993). Based on philosophical reflection and legal analysis, an array of new bioethics practices have entered into routine clinical care, the most recent being the Patient Self-Determination Act (Lynn and Teno, 1993).

Within the bioethics community, little attention has been paid to questions of ethnic or cultural diversity (for exceptions see Cross and Churchill, 1982; Hahn, 1983). A fundamental, and I would argue problematic, assumption of bioethics discourse has been universality. As Renee Fox has written, "There is a sense in which bioethics has taken its American [Western] societal and cultural attributes for granted, ignoring them in ways that

imply that its conception of ethics, its value systems, and its mode of reasoning transcend social and cultural particularities" (1990).

Embedded within the new end-of-life practices are unexamined assumptions that stem from specific Western traditions. Innovations in health care ethics that emphasize advance care planning for death or a patient's "right" to limit or withdraw unwanted therapy appear to presuppose a particular patient. This ideal patient has the following characteristics: (1) a clear understanding of the illness, prognosis, and treatment options that is shared with the members of the health care team; (2) a temporal orientation to the future and desire to maintain "control" into that future; (3) the perception of freedom of choice; (4) willingness to discuss the prospect of death and dying openly; (5) a balance between fatalism and belief in human agency that favors the latter; (6) a religious orientation that minimizes the likelihood of divine intervention (or other "miracles"); and (7) an assumption that the individual, rather than the family or other social group, is the appropriate decisionmaker. Underlying these assumptions—and the innovations in clinical practice, such as the Patient Self-Determination Act, which they have spawned—is a theoretical perspective that I will call, for the sake of simplicity, the "autonomy paradigm." I make the assumption that an emphasis on the principle of autonomy has characterized much bioethics discourse over the past 25 years.7

The idealized view of decisionmaking common within bioethics also assumes that health care providers offer real choices to patients at the end of life, rather than simply dictate patients' answers by how information is presented or how scientific facts about prognosis are framed. There is also the (questionable) assumption that patients and providers are equally powerful in the clinical relationship.8

Another theme in contemporary bioethics has been the overall relationship of grand-scale ethical theories (like the principle of autonomy) to more mundane matters, such as practical ethical judgments or decisionmaking (Jennings, 1990; Jonsen, 1991; Hoffmaster, 1992). There are many ways to frame this dichotomy; one may speak of the relationship between normative and descriptive inquiry, for example. The two activities yield quite different forms of knowledge. "Theory can be discussed and argued in serene and unspecific terms: read Sidgwick or Rawls, where five hundred pages can go by without a detail of the casuists' 'who, what, when, where, why, and how'?" as Jonsen notes (1991, pp. 14–15). Theory is "very loosely tethered to the ground and can float quite free" (Jonsen, 1991, p. 14). Attention to grand-scale theories precludes attention to the social context of clinical practice.

Empirical or descriptive research in bioethics aims to be grounded, seeking after the "who, what, when, where, why, and how." Recent shifts within academic bioethics have opened the door for empirical work by

anthropologists and other social scientists (Marshall, 1992). Attention to cultural diversity is made possible by this theoretical shift of focus.

Nonetheless, philosophical studies of the relevance of cultural difference to bioethics and decisionmaking are in their infancy. Pellegrino et al. (1992) and Veatch (1989) have both edited volumes that catalog the array of religious and cultural perspectives relevant to clinical bioethics. However, these works do not address the issue of potential conflicts in the United States when these myriad traditions collide (Orr et al., 1994). More fundamental is the question of whether an "ethnic perspective" on bioethics is philosophically justifiable, or desirable. African American philosophers express opposing views in a recent volume (Flack and Pellegrino, 1992).

Specific studies of how culturally diverse patients respond to innovations such as advance directives are only beginning to appear.9 Clinical case reports demonstrate the potential for conflict when patients and providers have conflicting expectations (Meleis and Jonsen, 1983; Muller and Desmond, 1992). Garrett and colleagues have demonstrated that African Americans differ from European Americans in their willingness to complete advance directives and desires about life-sustaining treatment (Garrett et al., 1993). Using survey research to investigate wishes about life-prolonging treatment, Caralis and colleagues found that significantly more African Americans and Hispanics, "wanted their doctors to keep them alive regardless of how ill they were, while more … whites agreed to stop life-prolonging treatment under some circumstances" (1993, p. 158).

Although results from surveys asking hypothetical questions about patient preferences have inherent limitations, the findings are intriguing and confirm the importance of political tensions. The probability is high that populations traditionally underserved by the health care system will find it hard to trust that physicians will make decisions in their best interest. Numerous studies have documented the higher morbidity and mortality of U.S. minority populations, as well as lack of access to care (Krieger, 1993; Adler et al., 1993). Empirical evidence documents a lower rate of organ donation by minority groups, perhaps another indication of lack of trust (Kasiske et al., 1991; Kjellstrand, 1988). With the increasing prevalence of managed care, suspicions will mount; economic incentives for the use of life-sustaining interventions will likely be transformed. Mistrust of government programs—and the health professionals seen as government agents—is justified by the historical record (see Jones, 1981, on the Tuskegee syphilis study).

Bioethics research paradigms, because of failure to include analysis of the social context within which end-of-life decisions are made, have failed to account for significant power differentials between patients and provid-

ers. My own research demonstrates serious discordance between patient's and family's perceptions of choice regarding end-of-life care for cancer.

Individual Choice and Research Allocation

Evidence, albeit anecdotal, from ethics committees in California (a state moving toward true cultural pluralism) suggests that the paradigm case brought to committees has changed. Whereas committees were well equipped to deal with cases of clear overtreatment and overuse of resources for a dying patient, the new case consists of a "minority" family demanding further care in the face of health care professionals' definitions of futile treatment.

Current end-of-life decisionmaking practices, based on Western concepts that privilege the individual and individual choice, will inevitably run into difficulties in a society that emphasizes difference. To cite but one example, the state of New Jersey has passed brain death legislation which allows for a religious and cultural exclusion. The statute specifically states that brain death will only be considered the criteria for determining that death has occurred if brain death is acceptable within the patient's or family's religious or cultural tradition. Such legislation raises the specter of families demanding continued treatment of individuals defined by the health care team as dead.

Culturally diverse U.S. populations will vary in their response to practice guidelines and standards based on health services research focusing on measurable outcomes. It is important to move beyond an understanding that blames individuals or rests on the assumption that culture forms a barrier to acceptance of rationally derived scientific facts.

Conclusions: Recommendations for the IOM Study

Based on this very brief overview of key concerns, I would like to make recommendations in the following three areas: (1) developing a research agenda to investigate cultural issues in end-of-life care and decisionmaking, (2) policy change in clinical bioethics practice, and (3) clinical education for health care providers.

Research: First, we need to develop a research agenda that will address how end-of-life decisionmaking is shaped within a particular cultural context. This research will need to be carefully crafted in order to avoid the pitfalls of simplistic and deterministic use of racial, ethnic, or cultural categories. The research needs to be constructed with an eye toward the complexity of power dynamics within the social setting of hospital, clinic, or nursing home. Culture and cultural differences are most effectively studied

using the interpretive techniques of the social sciences and humanities. Thus, it will be difficult to integrate research on cultural differences with traditional health services research. However, the rewards of developing new integrative approaches, methods that combine qualitative and quantitative research techniques, will be significant. Only by developing methods sensitive to the complexity of cultural diversity will we be able to avoid the political dangers of recognizing difference in insensitive ways.

Empirical research must address the following key issues: Is information about diagnosis and prognosis openly discussed? If not, how is such information "managed"? How is information about probabilistic outcomes understood? Is death (and its relative likelihood) an appropriate topic for discussion? Is the maintenance of hope, even in the face of bad outcomes, considered essential? How is decisionmaking shared (or delegated) by the individual patient and family? How is the option of quality of life versus quantity of life weighted? Do patients and families trust that health care providers will act in their best interests (within the context of changing reimbursement schemes)? This list undoubtedly needs expansion and refinement.

In addition to empirical research, scholars from bioethics and related disciplines must address fundamental normative issues: What are the implications of respecting cultural or ethnic perspectives in bioethics? How will questions of diversity intersect with questions of justice? When patients and families disagree with providers' assessments of outcomes, how should such disputes be mediated?

Clinical Bioethics Practices: Research results will inform the design and implementation of clinical bioethics practices. Up to now the cultural assumptions underlying existing practices have not been scrutinized. The relevance of these innovations for groups other than middle-class European Americans needs to be addressed. Based on the results of empirical investigation, clinical bioethics policies should be modified. The structure and functioning of institutional ethics committees must be examined to determine if differing perspectives can be heard. The possibility of greater family involvement in decisionmaking must be considered. Legal implications of modifying practices will need to be reviewed since they are likely to be significant.

Education: Clinical education about appropriate end-of-life10 care must incorporate means of addressing cultural diversity without stereotyping based on preconceived biases or views of particular ethnic groups. This is a challenge since clinicians will desire simple algorithms to help them reduce the enormous complexity of caring for patients from diverse cultural backgrounds. It is impossible to be an expert in every cultural tradition

encountered in practice, but it is possible to understand the principal points of variation—conceptions of the person, role of the family, future orientation, communication styles regarding diagnosis and prognosis, and so forth. The most important element of good teaching is emphasizing that patients and families should never be approached as "empty vessels," the bearers of particular cultures.11 Each patient needs to be approached first as an individual, a lesson which has been central to clinical education and thus does not require a major change of focus or direction.

In this very brief introduction—really an aerial view—of cultural diversity in end-of-life decisionmaking, I have only been able to hint at the most salient issues. In summary, future research, teaching, and practice guidelines should include:

- a sophisticated understanding of culture and health;

- careful use of categorizations based on race, ethnicity, and culture; and

- attention to the cultural assumptions embedded within clinical bioethics practices and their relevance to diverse patient populations.

Addendum

Three Case Narratives

CASE NARRATIVE: George Yengley (All names are pseudonyms.)

Mr. George Yengley is a 59-year-old "Anglo" European American man whose pancreatic cancer was discovered when he collapsed on the street and was taken to the emergency room of the local public hospital. Mr. Yengley's response to his diagnosis and the treatment offered him most closely approximates the idealized patient of the autonomy paradigm. His life story reflects a long-term preoccupation with independence; in fact, he spent most of his adult life as a self-proclaimed loner and only reunited with family (in this instance a niece) when he became ill and was unable to live alone. Even in illness, he remained estranged from his wife and children, and a major worry for him was being burdensome for his niece and her family.

Mr. Yengley was quite open in discussing both diagnosis and the eventual outcome of his cancer. He used the word cancer in discussing his illness, avoiding euphemisms. Describing his surgery he stated: "They said that they operated but couldn't get all of it and there was no hope. And you have three months to a year to live. Well, I really think that prediction is wrong, right now. … So then you start thinking about your death." Note that although he accepts the overall prognosis, he remains convinced that

the timing offered by the physicians is wrong in his case, that he will beat the numbers.

Mr. Yengley's niece was also open in talking about the illness: "I know he has cancer, pancreatic and stomach. And I know at the time he was diagnosed, he had three months to a year to live." Following his initial surgery, the health care team suggested a treatment regimen of radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Mr. Yengley began this treatment course, but stopped all treatment soon thereafter, a course he initiated because of the unpleasant side effects of treatment. Once settled with his niece, he made specific plans for his funeral and began choosing a nursing home/hospice where he could receive end-of-life care, reflecting his desire not to "die at home," which he felt would burden his family.

George Yengley's social worker highlighted the unique elements of his story. "It's interesting because he is such an exceptional guy. He is one of the very few who actually say, 'no, I don't want any more treatment.'… He is dealing with his own prognosis and he knows radiation may or may not help. He knew it didn't make him feel good so he stopped. I have a lot of admiration for that. We support his decision." Mr. Yengley's style was much appreciated by the staff, who described him as "strikingly realistic." His oncologist's comments reflect the degree of congruence between Mr. Yengley and the staff. "He very quickly showed himself to be someone who was able to make decisions for himself and not be lost in a sea of emotions."

Embedded within the new end-of-life practices are unexamined assumptions that stem from specific Western traditions. Innovations in health care ethics that emphasize advance care planning for death or a patient's right to limit or withdraw unwanted therapy appear to presuppose a particular patient. This ideal patient has the following characteristics: (1) a clear understanding of the illness, prognosis, and treatment options that is shared with the members of the health care team; (2) a temporal orientation to the future and desire to maintain "control" into that future; (3) the perception of freedom of choice; (4) willingness to discuss the prospect of death and dying openly; (5) a balance between fatalism and belief in human agency that favors the latter and minimizes the likelihood of divine intervention (or other "miracles"); and (6) an assumption that the individual, rather than the family or other social group, is the appropriate decision-maker. Patient George Yengley comes the closest to this ideal patient.

CASE NARRATIVE: Hung Long Lin

Mr. Lin's cancer was diagnosed in China before he immigrated to the United States about one and one-half years ago with his wife and their two sons. The older son attends junior college and speaks English well, always

accompanying his monolingual father to the clinic. Since arrival in the United States, Mr. Lin has received treatment for his locally invasive nasopharyngeal cancer, a cancer that has progressed to the point of being immediately life-threatening due to the high likelihood of hemorrhage from major blood vessels in his neck. He has been treated with both radiation therapy and chemotherapy. In addition to conventional oncological treatments, he is taking traditional Chinese medicine.

In contrast to some Chinese patients, Mr. Lin used the word cancer (as opposed to tumor) in discussing his illness with the Cantonese-speaking interviewer. His son elaborates, "We don't mind saying 'cancer' because we all know that my father has this illness. But we all do our best not to say that.… We don't know how long he will live, but we want him to enjoy every day." Other Chinese patients in the study never mentioned the word cancer in interviews, using the more neutral Cantonese term for tumor. Yet like Mr. Lin, it was clear they understood the severity of the situation in spite of their hesitancy to openly name the disease.

The professionals caring for Mr. Lin began with the assumption that he must be fully informed. Since Mr. Lin speaks no English, the staff generally rely on Mr. Lin's son to translate. This opens up the possibility of conflicting notions of what constitutes appropriate disclosure. Mr. Lin's son complained, "For us Chinese, we are not used to telling the patient everything, and patients are not used to this either. If you tell them, they can't tolerate it and they will get sicker."

During one visit to the clinic, the physician wanted Mr. Lin's son to explain that chemotherapy had not been effective in his case and that there were no more treatments available. The son was quite distressed. "I did not want to translate this to my father, but the doctor insisted on telling him everything.… The doctor found the Chinese-speaking social worker to translate for him and told him everything." When interviewed separately, the oncologist treating Mr. Lin discussed his older son: "He came to every visit and was always clamoring for more chemotherapy for his dad although it was completely unrealistic." In this case, the physician did not succeed in imposing autonomy on the patient over the wishes of the son, who chose to maintain ambiguity and thus hope.

CASE NARRATIVE: Elena Alvarez

Elena Alvarez is a 48-year-old woman who has lived in the United States for many years. Originally from El Salvador, her English is very limited. Before her diagnosis with ovarian cancer, she worked as a child care provider. Her family consists of a brother and her mother; she lives with her elderly mother who has many health problems of her own. Her

disease has progressed despite surgery, initial chemotherapy, and a number of attempts at "salvage" chemotherapy.

Elena Alvarez spoke openly about her cancer diagnosis with members of the clinic staff, but maintained a complex silence within her family. For many months she did not name the disease with her elderly mother, preferring to shield her from this information. As her illness progressed, Ms. Alvarez' mother eventually learned that her daughter had cancer. However, the severity of the illness was never addressed. One of the nurses commented, "The other thing that Elena said to us when we had this big meeting was that she has not told her mother the truth about her illness. She can't tell her mother the truth about her illness. So I'm sure they haven't had a real honest conversation about what is going on."

From the point of view of her health care providers, Ms. Alvarez faced many decision points. "However, like many of the other patients in our study, she did not experience any sense of choice. In interviews she stated over and over, "You just have to do the treatment, there isn't an alternative. You get treatment to prolong your life and get well, or you let yourself die." Over a nine-month period, she always "CHOSE" more treatment. During the informed-consent process for entry into the research, we told the patients that we were studying decisionmaking. Some patients, particularly women, found this perplexing and wondered what we were "really studying," since they did not experience their medical care as including decisions. When discussing her "last" drug, tamoxifen, Ms. Alvarez said, "I wait for life. I have the point of view that I am going to be cured. This is going to be my drug. This is going to cure me."

The comments of Elena Alvarez reflect the tension between her beliefs that no choices existed, and the health care team's demands that she make decisions. When asked who was the most important person making decisions about her treatment, Elena answered, "I am," but immediately complained, "Here in this country they don't give you an alternative but to do it alone. … In other countries they tell the family and the family has influence. The family decides. Here the patient has to decide for themselves (sic). There is no alternative." She raises two questions: Are there real options, and should the individual patient be shouldered with making decisions alone?

The issue of prognosis was equally complex. Nurse Terry Miller noted, "One of the things that Dr. Ingle and I talked about was, 'when is he going to say that enough is enough,' because this woman is not going to be cured. She is going to die of the disease. Several months ago we sat down with Elena and said, 'it's progressing and we don't know what else we can do for you.' And I asked her at that time, when was she going to know that enough was enough. She told me she would know that when the doctor told her there was nothing left to do." In seeming contradiction to the funda-

mental assumptions of the autonomy paradigm, Dr. Ingle found it very difficult to discuss the patient's likely prognosis. He explained his frustrations by rehearsing a hypothetical conversation with his patient: "I want to encourage you to keep going with this chemo, but oh, by the way, you're still not going to do well, and you probably only have six months to live. It's kind of hard, and I didn't reiterate that, to tell the truth." The problem is apparent; the doctor is giving the patient mixed messages, and everyone wants someone else to make the hard decisions. Dr. Ingle continued, "She lets me make the decisions for her. In Elena's case I'll tell her what I think is best for her, and I tend to push pretty aggressively with Elena. I'm not willing to just sort of like, let her go." The result is a long delay in acknowledgment that further treatment is futile, a dynamic discussed in many of the background papers written for the IOM workshop.

The situation of Elena Alvarez was complicated by the need for language interpretation. I was able to observe a long and complicated clinical session, involving the patient, the clinical nurse specialist, oncologist, and social worker. A Spanish language interpreter was also present since the encounter was foreseen to be important: would the patient want further salvage chemotherapy for her disease, which had recurred despite numerous interventions (a treatment decision about which she ultimately felt she had no choice)? Although communication is never simple, some elements of failed communication are not overly complex and were evident in the clinical encounter. Throughout the exchange, I noted many instances in which statements by either the patient or one of the team members were simply not translated. The physician was offering chemotherapy, the nurse was reminding the patient that she mustn't wait until it was too late, meaning that she was too ill to travel, if she wanted to return to her native El Salvador. In this cacophonous five-way exchange, it was difficult to determine what "got through" to the patient, who was weeping softly throughout. As discussed earlier, like many patients, Elena appeared to perceive no choice but to follow the physician's option of additional chemotherapy. In later interviews, Dr. Ingle described the patient's prognosis as extremely poor regardless of therapeutic endeavors.

But of most interest was the role of the interpreter in placing the clinical session in a certain cultural context. Toward the end of the interview, the interpreter spoke softly with the patient for some time, not volunteering to translate his own remarks for others in the room. Seemingly distressed by the bluntness of the conversation he had just been translating, he ended the exchange by relating a story to Elena, a story suffused with hope. Once the interpreter had known a person with cancer who was told he would only live for two months, and the person was still alive nine years later! Is the interpreter trying to compensate for the teams' lack of sensitivity to a culturally shared (between patient and translator) need to maintain hope?

In this type of exchange, which voice captures the patient's attention? The role of the white-coated interpreter, who must appear to the patient as a full member of the team, needs further exploration.

Endnotes

-

2.

This comment is based on my personal experience serving on ethics committees in long-term care facilities in San Francisco, including On Lok Senior Health Services and Laguna Honda Hospital.

-

3.

Unpublished table produced by author from census data.

-

8.

Recent work in bioethics, such as Brody's The Healer's Power (1992), has begun to address questions of power in the doctor-patient relationship.

-

9.

A large empirical study of cultural diversity and advance directives is currently under way at the University of Southern California. Results are not yet available.

References

Adler, Nancy E., Boyce, W. Thomas, Chesney, Margaret A., et al. 1993. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health: No Easy Solution. Journal of the American Medical Association 269:3140–3145.

Anspach, Renee R. 1987. Prognostic Conflict in Life-and-Death Decisions: The Organization as an Ecology of Knowledge. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 28:215–231.

Barker, Judith C. 1992. Cross Cultural Medicine (special issue). Western Journal of Medicine 157:248–254.

Barnes, Donelle, Koenig, Barbara A., et al. 1993. "Telling the Truth" about Cancer: The Ambiguity of Prognosis for Culturally Diverse Patients. Paper presented at the Society for Applied Anthropology Annual Meeting, San Antonio, Texas.

Brody, Howard. 1992. The Healer's Power. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

California Association of Homes for the Aged. 1993. Inter-Agency Ethics Committee.

Callahan, Daniel. 1993. The Troubled Dream of Life: Living with Mortality . New York: Simon & Schuster.

Caralis, PV, et al. 1993. The Influence of Ethnicity and Race on Attitudes toward Advance Directives, Life-Prolonging Treatments and Euthanasia. Journal of Clinical Ethics 4:155–165.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993. Use of Race and Ethnicity in Public Health Surveillance. Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report 42.

Childress, James F. 1990. The Place of Autonomy in Bioethics. Hastings Center Report 20(1):12–17.

Churchill, Larry R. 1979. Interpretations of Dying: Ethical Implications for Patient Care. Ethics in Science and Medicine 6:211–222.

Cross, Alan W., and Churchill, Larry R. 1982. Ethical and Cultural Dimensions of Informed Consent: A Case Study and Analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine 96:110–113.

Flack, Harley E., and Pellegrino, Edmund D. 1992. African American Perspective on Bioethics. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Fox, Renee C. 1990. The Organization, Outlook and Evolution of American Bioethics: From the 1960s into the 1980s. In Social Science Perspectives on Medical Ethics, G. Weisz, ed. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Garrett, J., et al. 1993. Life-Sustaining Treatments During Terminal Illness: Who Wants What? Journal of General Internal Medicine 8:361–368.

Glazer, Nathan and Moynihan, Daniel P. 1963. Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians and Irish of New York. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Gupta, Akhil, and Ferguson, James. 1992. Beyond "Culture:" Space, Identity and the Politics of Difference. Cultural Anthropology 7:6–23.

Hahn, Robert. 1983. Culture and Informed Consent. In: Making Choices. Report of the President's Commission for Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research, pp. 37–62. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Hahn, Robert A., Mulinare, J., and Teutsch, S.M. 1992. Inconsistencies in Coding of Race and Ethnicity Between Birth and Death in U.S. Infants. Journal of the American Medical Association 267:259–263.

Helman, Cecil. 1990. Culture, Health, and Illness, 2d Edition. Boston: Wright.

Hoffmaster, Barry. 1992. Can Ethnography Save the Life of Medical Ethics? Social Science and Medicine 35(12):1421–1431.

Jennings, Bruce. 1990. Ethics and Ethnography in Neonatal Intensive Care. In Social Science Perspectives on Medical Ethics, G. Weisz, ed. Hingham, Massachusetts: Kluwer, pp. 261–272.

Jones, James. 1981. Bad Blood: the Scandalous Story of the Tuskegee Experiment. New York: Free Press.

Jonsen, Albert R. 1991. Of Balloons and Bicycles or the Relationship Between Ethical Theory and Practical Judgment. Hastings Center Report 21(5):14–16.

Kalish, Richard A., and Reynolds, David K. 1976. Death and Ethnicity: A Psychocultural Study. New York: Baywood (1981 reprint).

Kasiske, B.L. Neylan, J.F., Riggio, R.R., et al. 1991. The Effect of Race on Access and Outcome in Transplantation. New England Journal of Medicine 324:302–307.

Kjellstrand, C.M. 1988. Age, Sex, and Race Inequality in Renal Transplantation. Archives of Internal Medicine 148:1305–1309.

Kleinman, Arthur. In Press: Anthropology of Bioethics. In Encyclopedia of Bioethics, Warren T. Reich, ed. New York: Macmillan.

Kleinman, Arthur, and Kleinman, Joan. 1991. Suffering and Its Professional Transformation: Toward an Ethnography of Interpersonal Experience. In Culture, Medicine, Psychiatry 15:275–301.

Koenig, Barbara A., et al. 1992. Cultural Pluralism and Ethical Decision-Making: Meanings of Autonomy to Patients and Families Facing Life-Threatening Cancer. Paper presented at American Anthropological Association Annual Meeting, San Francisco, California [Under revision for submission.]

Krieger, Nancy. 1993. Analyzing Socioeconomic and Racial/Ethnic Patterns in Health and Health Care. American Journal of Public Health 83:1086–1087.

Lamphere, Louise. 1992. Structuring Diversity: Ethnographic Perspectives on the New Immigration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lock, Margaret. 1993a. The Concept of Race: An Ideological Construct. Transcultural Psychiatric Review 30:203–227.

Lock, Margaret. 1993b. Education and Self Reflection: Teaching About Culture, Health and Illness. In Health and Cultures: Exploring the Relationships, R. Masi, et al., eds. Oakville, Ontario: Mosaic Press.

Lynn, Joanne, and Teno, Joan M. 1993. After the Patient Self-Determination Act: The Need for Empirical Research. Hastings Center Report 23:20–24.

Marshall, Patricia. 1992 Anthropology and Bioethics. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 6:49–73.

Meleis, Afaf I., and Jonsen, Albert R. 1983. Ethical Crises and Cultural Differences. Western Journal of Medicine 138:889–893.

Muller, Jessica H., and Koenig, Barbara A. 1988. On the Boundary of Life and Death: The Definition of Dying by Medical Residents . In Biomedicine Examined, Margaret Lock and Deborah Gordon, eds. Boston: Kluwer.

Muller, Jessica H. and Desmond, Brian. 1992. Ethical Dilemmas in a Cross-Cultural Context—A Chinese Example. Western Journal of Medicine 157:323–327.

Office of Management and Budget. 1978. Directive No. 15: Race and Ethnic Standards for Federal Statistics and Administrative Reporting. Statistical Policy Handbook. Washington, D.C., U.S. Department of Commerce, Office of Federal Statistical Policy and Standards.

Orona, Celia J., Koenig, Barbara A., and Davis, Anne J. 1994. Cultural Issues in Non-Disclosure. Cambridge Quarterly for HealthCare Ethics 3(3).

Orr, Robert D., Marshall, Patricia A., and Osborn, Jamie. 1994. Cross-Cultural Considerations in Clinical Ethics Consultations. (Submitted.)

Osborne, N.G. and Feit, M.D. 1992. The Use of Race in Medical Research. Journal of the American Medical Research 267:275–279.

Pellegrino, Edmund D., et al. 1992. Transcultural Dimensions of Medical Ethics. Baltimore, Maryland: University Publishing Group.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy. 1992. Death without Weeping: The Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sharp, John. 1988. Introduction. In South African Keywords: the Uses and Abuses of Political Concepts. Cape Town and Johannesburg: David Philip.

Sheldon, T.A., and Parker, H., 1992. Race and Ethnicity in Health Research. Journal of Public Health Medicine 14:104–110.

Slomka, Jacqueline. 1992. The Negotiation of Death: Clinical Decision-Making at the End of Life. Social Science and Medicine 35:251–259.

Taylor, Charles. 1992. Multiculturalism and the Politics of Recognition . Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Veatch, Robert M. 1989. Cross Cultural Perspectives in Medical Ethics . Boston: Jones and Bartlett.