4

The Health Care System and the Dying Patient

Why are you afraid? I am the one who is dying!…But please believe me, if you care, you can't go wrong.…Death may get to be routine to you, but it is new to me.

Anonymous, American Journal of Nursing, 1970

With help and support from family, friends, and others in the community, many people can live their lives, while dying, with some or considerable independence from the health care system. Many, if not most, however, draw heavily on that system for care—and caring—in the form of clinical services, counseling, and practical assistance with both medical and nonmedical needs. Thus, while the role of family and community resources should be acknowledged and strengthened, it is also essential to understand how care systems serve patients well and poorly and to identify the system characteristics that contribute to poor care. Such understandings, which will depend on better data and research than now exist, will help provide the basis for steps to remove the impediments to good care and to fortify the foundations for reliably excellent care.

In general, care systems—both as discrete organizations and as unevenly connected arrays of community institutions and services—require people (supported by facilities and processes) who are prepared to determine what care is appropriate, to arrange its provision, and to monitor performance for consistency with organizational and external norms. Broadly, this means having the capacity to provide or arrange for

- symptom prevention and relief;

- attention to emotional and spiritual needs and goals;

- care for the patient and family as a unit;

- sensitive communication, goal setting, and advance planning;

- interdisciplinary care; and

- services appropriate to the various settings and ways in which people die.

These process of care elements are, in a sense, statements of expectations for the care system. Most of these elements were discussed in Chapter 3, which emphasized the importance of sympathetic but clear consideration of prognosis and goals and fitting care strategies to circumstances. This chapter considers the major settings of care in which people die and identifies questions about the ways care is structured, provided, and coordinated. It concludes by considering aspirations for an ideal care system and what this implies for the mix of organizations, programs, settings, personnel, procedures, and policies that make up care systems.

Unlike new mothers or women undergoing mastectomies, who have recently been the subject of highly publicized criticisms of early discharge, dying patients are not themselves a potent lobbying group and their survivors are often exhausted, grieving, and expected to put their lives back together and move on. Thus, health care professionals, managers, and others have a particular responsibility to press for care systems that people can trust to serve them well as they die.

Characterizing Care Systems

Trying to present a coherent picture of health care systems as they serve—or fail to serve—those who are dying is not easy. First, the two million people who die each year have both variable and common characteristics and needs. Second, the organizations and personnel that may be involved in end-of-life care are likewise numerous and variable. Nationally, there are roughly 6,000 hospitals, 16,000 nursing homes, 11,000 to 15,000 home health care and hospice agencies, 650,000 generalist and specialist physicians, 2 million nurses, tens of thousands of social workers involved in health care,1 and numerous other categories of health personnel and facilities including several hundred health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and other managed care and health insurance arrangements. Third, data about care at the end of life are very limited.

Even the term health care system has no fixed meaning. It can be used in at least four different ways—not because people are being careless in their language but because the term is intrinsically general and capable of applying to several situations. First, the term health care system may be used to describe and analyze a community's or region's array of health care

organizations and services, whatever their relationships. This is consistent with one dictionary definition of a "system" as a set of objects grouped together for classification or analysis (The American Heritage Dictionary, 3d ed.). In this usage, the health care system in New York City could be characterized as an aggregation of loosely interacting (sometimes cooperating, sometimes competing, sometimes self-absorbed) components within a large, socially and economically complex geographic area. Fragmentation has been cited as the key characteristic of such systems in the United States (Shortell et al., 1996). Although they may be viewed as rather disorderly systems, they are—analytically—still systems rather than nonsystems.2 The deficiencies of community health care systems, in the past, prompted a variety of voluntary and regulatory efforts to plan and control the development of health resources (especially facilities and advanced technologies). In part as a result of their weaknesses and in part as a result of shifting political tides at the community and national level, these sorts of health-planning mechanisms have largely been abandoned in favor of more market-based strategies.

In a second and broader sense, the term health care system may also encompass the norms, public policies, and social values that shape the delivery of health care in a community or a society. This is consistent with another dictionary definition of a "system" as the prevailing social order (The American Heritage Dictionary, 3rd ed.) Thus, a reference to the Canadian health care system or the American health care system may signify not just a collection of institutions and personnel but also a culture.

A third and much narrower use of the term applies to a particular entity that integrates a comprehensive range of health care services and the facilities and personnel to provide those services (Coddington et al., 1996; Shortell et al., 1996). The integration is formal and institutionalized through explicit controls related to personnel, budgets, and other matters. Systems in this sense may be more or less geographically concentrated, as is the Henry Ford Health System in Michigan, or geographically dispersed, as is the U.S. military health care system, which is not only national but international. 3 Finally, an even narrower use of the term is as a rough synonym for

a provider organization such as a hospital, nursing home, or hospice program.

In this chapter, the discussion tends to focus on community health care systems, but it will be clear that such systems are embedded in a national health care system and include organizational systems as components. The committee uses the term care system to highlight the special role in care for terminally ill patients—and frail individuals more generally—of nonmedical services such as spiritual and bereavement counseling, respite care, and housekeeping assistance. In addition to formal or organized health care systems, informal care systems can also be distinguished; they include the family, religious communities, and folk culture (Kleinman, 1978; Kleinman et al., 1978). These systems play a central role for many if not most patients and families, but they were not the focus of this study.

Illustrative Case Histories

To illustrate the variability of care for those who are dying, this section presents several more cases. As in Chapter 3, these cases do not exactly describe a single patient or institution or represent statistically typical patients. The cases synthesize committee experiences, cases in the medical literature, research findings, and specific problems reported to the committee. Several describe situations that particularly strain care systems.

"Ellen Artbur"

This case, synthesized from the hospice literature and committee experiences, illustrates a patient and family for whom a limited range of hospice services work well and whose personal circumstances support living well while dying.

Ellen Arthur, a 78-year-old retired teacher diagnosed with kidney cancer, underwent surgery and a trial of experimental chemoimmunotherapy. Tests then showed that the cancer had spread to her lungs and bone. She was incurably ill but not imminently dying and could reasonably be expected to live for another year, perhaps two. She felt fairly well except for mild fatigue. She and her husband were financially comfortable, well educated, and surrounded by supportive family and friends. They reviewed the durable power of attorney and related documents that they had prepared many years ago.

After several months of fairly normal activity, pain and weakness began to require an increasing amount of medication. Ellen Arthur's physician concluded that she could very well die within the next six months—probably less—and certified this so that she qualified for the Medicare hospice benefit. Her physician coordinated care with the hospice medical

director who, in turn, worked with the patient, her family, and an interdisciplinary team to implement the care plan as initially designed and later adjusted as the illness progressed. A hospice nurse was the center of the care team, which focused on two primary problems—fluctuating pain and fatigue. Protocols allowed the nurse to adjust pain medications within defined boundaries, and she advised ways to prevent or soothe other symptoms. For example, she suggested ice chips and glycerin swabs to ease dry mouth and advised balancing rest and activity to reduce the burden of fatigue. The family needed little other direct service from the hospice. Physical therapy and other medical services were not indicated, and the family found emotional and spiritual comfort in their friends and their faith and in reviewing their life together. Friends also pitched in to provide occasional practical help with meals, errands, cleaning the house, and respite time.

John Arthur was informed about how to recognize changes in his wife's condition, especially signs that death was imminent. He knew that if something happened that he could not handle—seizures, for example—he could call the hospice any time, day or night, and help would be sent. The Arthurs were informed that if they called 911 in such an emergency, the protocol for paramedics in their jurisdiction required attempts at resuscitation and other interventions and transport to the hospital. Ellen Arthur died at home with her husband at her side.

"Solomon Katz"

This example, adapted from a case analyzed in The New England Journal of Medicine (Morrison et al., 1996) illustrates aggressive medical culture, non-beneficial and even inhumane technical interventions, and disregard for patient and family concerns and preferences. It is marked by fragmented services and failure to provide appropriate referrals to hospital and community resources. No one had overall responsibility for this patient's care and well-being.

Solomon Katz, a 75-year-old retired postal worker, experienced progressive weakness in his left leg for over a year, but he sought care in the emergency department only after he fell and could not get up by himself. After an array of tests, he was diagnosed with lung cancer metastatic to the brain. He accepted medication but refused a lung biopsy. Hospital staff described him as "in denial," but a psychiatric consultant assessed him as reacting appropriately and capable of making his own decisions. He revealed that his wife died of cancer two years earlier; he did not want to go through the treatments she had. After continued pressure from the oncology team, he agreed to a biopsy, which confirmed the previous diagnosis. They offered options for life-prolonging but invasive treatment; he declined. He was discharged home with home care and follow-up appoint-

ments at two clinics. The medical staff did not refer him to the hospital's social work staff, and no one sat down with Solomon Katz and his family to talk with them about the prognosis, palliative care options, or their concerns and preferences. He did not keep his follow-up appointments, but no one checked to see why.

Three months later, Mr. Katz was again brought to the emergency department following grand mal seizures. He was lethargic and could not talk; a CT scan showed progression of the brain tumor, including partial brain stem herniation. He was started on intravenous medications and fluids, and then oxygen and nasogastric tube feedings. The neurology team wanted to resect the brain tumor. His son, a grocery store clerk, refused surgery and asked for a do-not-resuscitate order on the basis of his father's previously expressed wishes. During the next three weeks, Mr. Katz was minimally responsive but repeatedly removed the nasogastric tube despite restraints. After pressure from the hospital staff, the son agreed to insertion of a percutaneous gastrotomy tube. On the following day, Solomon Katz died of a cardiac arrest with no family present. The son was upset by the entire experience, particularly when he later learned that his father's dying could have been a less brutal experience and that his care could have been managed differently with an emphasis on understanding his goals as his life ended and providing physical and emotional comfort. The case attracted the attention of the hospital ethics committee, which concluded such clearly inappropriate care indicated serious system problems. It began to mobilize an institution-wide effort at self-examination, staff education, process changes, and quality measurement and improvement.

"Dorothy Chang"

The next case presents a middle-age woman who died in an intensive care unit following a cascade of complications related to a bone marrow transplant and other medical problems. When it was time for life support to be ended, a protocol was followed that emphasized patient comfort and attention to the family.

Dorothy Chang was a 54-year-old woman with aplastic anemia who received a bone marrow transplant in August. She tolerated the procedure well, but her discharge from the hospital was delayed due to recurrent bacterial infections. Her infections resulted from a narrowed esophagus. An attempted corrective procedure was complicated by rupture of the esophagus and a life-threatening infection that required placement of a drainage tube in the chest and intravenous antibiotics in the ICU. She remained intubated with recurring pneumonia.

The pneumonia slowly improved, but a trial with removal of the ventilator failed. Significant muscular weakness developed, exacerbated by

chronic steroid use. A tracheostomy was performed, and a feeding tube was placed with some difficulty. In early November, a head CT scan revealed a lesion consistent with a fungal brain abscess. Despite treatment, another CT revealed advancing disease, and a brain biopsy suggested Aspergillus infection, which occurs mainly in immune-compromised people and is very resistant to treatment.

Ms. Chang's condition declined further. She became minimally responsive, and her husband agreed with her physicians that further life-supporting treatment would only prolong death. With support from the hospital's comfort care team, Ms. Chang was moved to a more private area where her family could be with her when the ventilator was removed by an experienced physician known to the family. After all monitors and other supports were removed except an intravenous morphine drip, she was given intravenous morphine and midazolam to ensure that she would not experience distress. After the ventilator was disconnected, her breathing became irregular and stopped, and then her heartbeats began to pause before ceasing. Her family remained quietly with her for a period after death was declared. Following this patient's death after more than four months in the ICU, the ICU director decided that this case needed a careful review to identify any flaws in the unit's performance and areas for improvement. The initial assessment was that both the intensive treatment and its eventual withdrawal were appropriate for the patient's particular combination of problems but that the decision for esophageal dilation should be reviewed with gastroenterologists.

"Millie Morrisey"

The problems of appropriate end-of-life care for nursing home patients are increasingly being recognized. This case illustrates both inadequate expertise in palliative care and faulty organizational procedures for assuring that patient and family wishes are respected.

Millie Morrisey, an 86-year-old retired clerical worker, suffered from Alzheimer's disease and congestive heart failure. Before her illness became so severe, she and her niece had discussed her future, and she prepared a living will that expressed her wishes, including that resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, and other life-prolonging measures not be attempted in a medical crisis. She did not want to burden her niece, and she accepted that nursing home care would be the best option when she could no longer safely be left by herself, which happened about a year later.

After two years of nursing home care, Millie Morrisey developed pneumonia and respiratory distress. As had been its custom, the nursing home staff called an ambulance. Documentation of preferences—which included foregoing antibiotics, mechanical ventilation, and tube feeding—were nei-

ther sought nor readily accessible in her chart. The hospital quickly admitted her to the ICU, initiated antibiotics and mechanical ventilation, and used physical restraints so that she would not dislodge the tubes and lines to which she was connected. She mostly did not seem to understand what was happening and was agitated and tearful. After three days during which her niece informed the ICU team of her aunt's wishes, Millie Morrisey was successfully withdrawn from the ventilator and died a few days later, receiving comfort care only. The niece was still upset, and the nursing home staff concluded they needed to avoid similar problems in the future. The nursing director learned that she could participate in a new statewide working group comprised of many health care, social service, and religious organizations that were attempting to devise clinical and administrative guidelines to understand and honor patient and family goals and to assure excellent end-of-life care.

"Darrell Henson"

This case demonstrates the involvement of nontraditional family. It also underscores the role that poor quality care can play in turning a patient's attention to suicide.

Darrell Henson, a 67-year-old owner of a small business, was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He had surgery and remained in remission for two years. Around Thanksgiving, the cancer reappeared in bone metastases, and Mr. Henson began to suffer terribly from pain and nausea. The medications prescribed by his physician did little to help, but the physician feared being accused of overprescribing narcotics and was reluctant to do more. Mr. Henson begged his companion, Charles Jones, to help him die because life seemed unendurable with such pain. Mr. Jones, distressed by his companion's suicidal thoughts, called another physician, one who had cared for his mother. This doctor visited Mr. Henson at home, did a careful assessment of his pain and other symptoms, and developed a care plan that emphasized effective pain relief and supportive home services. Although not a conventionally religious man, Mr. Henson was relieved not to violate the prohibitions against suicide taught to him in childhood. He was able to remain home, celebrate Christmas with his companion and their friends, and—despite weakness—say his goodbyes before dying in January.

"George Lincoln"

This case illustrates the disruptions that may be caused by health care restructuring and consolidation.

George Lincoln was an 84-year-old retired engineer whose health gradually deteriorated as multiple organ systems began to fail. Through his former

employer's health plan, he had long been enrolled in a large HMO. He had been pleased with the HMO, which arranged much appreciated hospice care when his wife died of breast cancer several years earlier. Then, however, the HMO was sold to a corporation with out-of-state headquarters, his personal physician was not on the new provider list, many of his numerous medications were switched to lower-cost drugs, and referral to a cardiologist experienced with very old patients proved difficult. Mostly confined to his home (and often to his bed) and experiencing considerable physical distress but still mentally alert, Mr. Lincoln concluded—with considerable equanimity—that "my time is coming." He raised the issue of hospice care with his new primary care physician. He discovered that the HMO's long standing relationship with a community hospice had been terminated in favor of referrals to a fairly new organization. Mr. Lincoln was not told that as a Medicare beneficiary he was not limited to this hospice, and he found the new hospice provided a much-reduced level of care—and caring. He was, in any case, too fatigued and depressed to complain.

The cases above and in Chapter 3 highlight some of the positive and negative features of the care systems available to dying patients and those close to them. They vary in the degree to which care systems help the process of dying be, as described in Chapter 1, free from avoidable distress and suffering for patients, families, and caregivers; in general accord with patients' and families' wishes; and reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural, and ethical standards. Some examples were constructed to show patients who suffered reasonably avoidable distress; some involved disregard for patient and family wishes and perhaps violated clinical or ethical standards; several showed people and institutions attempting to cope with changing expectations or to correct problems. The sections below consider different settings of care from a more general analytical perspective.

Settings For End-of-Life Care

As described in Chapter 2, people die in many settings—mainly hospitals, nursing homes, and homes. Each setting is appropriate and feasible under some circumstances and not under others. Not only are home, hospital, and nursing home settings quite different from each other, each category encompasses great variability. This discussion starts with the hospital because it is still the most frequent site for end-of-life care, despite increased pressure from various sources to shift care to other settings. Later sections consider nursing homes, home care as part of a hospice program, home care without hospice, and coordination of care within and across settings. Transitions from one setting to another create many problems as the weak or even nonexistent links among health system components are exposed. Con-

sistent with other chapters, one problem in drafting this chapter was the relative lack of descriptive and evaluative data on the experience of dying patients and the effects of different settings and processes of care.

Hospitals

Although the situation is changing, more deaths occur in hospitals than in other settings, and most people receive some hospital care—brief or extended—after being diagnosed with serious progressive illness. Nonetheless, curing disease and prolonging life are the central missions of these institutions. Hospital culture often regards death as a failure, in part because modern medicine has been so successful in rescuing, stabilizing, or curing people with serious medical problems and in part because a significant minority of acutely ill and injured patients who die often do so before the end of a normal life span.

A major challenge in hospital care is identifying better ways to maintain vigorous efforts to cure illness and prolong life while, at a minimum, avoiding needless physical and emotional harm to patients who die. Every hospital's goal should be to provide as good a death for the patient and family as a patient's illness and circumstances permit.

Shortcomings in hospital care have been documented in a number of areas. A large study that attempted both to understand hospital care of patients with advanced illnesses and to improve that care identified opportunities for improvements in patient-physician communication, understanding and honoring of patient preferences, and symptom management (SUPPORT Principal Investigators, 1995). It also found considerable amounts of intensive interventions in the days before death, a finding that the investigators found troubling but that some critics argued might be appropriate and consistent with patient's wishes (Emanuel, 1995b; Lo, 1995). The study also found that the strategies designed to improve care did not appear to have modified behavior or outcomes

Other studies, cited in Chapters 3 and 5, have found problems related to unrelieved symptoms in hospitalized patients, poor documentation of patient preferences for care, early discharge of dying patients, and underuse of home care. As discussed further in Chapter 6, the financial incentives for hospitals to discharge patients early warrant reexamination in the context of end-of-life care.

The growth of hospice combined with pressures to minimize hospital use is shifting more care to other settings, often the home, sometimes a nursing home. This shift can be expected to continue as physicians, nurses, social workers and others working with hospitals, hospices, nursing homes, and professional and community education programs help dying patients

and their caregivers understand how to cope with the period of dying and the moment of death without reflexively turning to hospitalization.

The committee identified a number of basic issues and questions that will be generally relevant for hospitals caring for gravely ill and dying patients. They are offered in part as a guide for hospitals concerned about understanding and improving care and in part as a guide to the formulation of a research agenda. For the most part, the issues and questions outlined below translate into matters of staffing and procedures involving personnel with appropriate attitudes, skills, and knowledge; in some cases, they involve physical design of facilities.

- How well are patients and families informed about who is responsible for care, what they can expect, and who they can look to for information and assistance? How specifically are the preferences and circumstances of patients and families determined, assessed, recorded, and accommodated? Are processes focused narrowly on written orders or more broadly on advance care planning? What provisions are made for children, non-English speakers, cultural minorities, and others who may not fit routine administrative and clinical procedures?

- What internal or external expertise is available to help clinicians, patients, and families with clinical evaluation, symptom prevention and management, advance care planning, and decisions about foregoing or withdrawing treatments, bereavement support, and other matters? How is this expertise organized and shared? Are other staff routinely educated about the availability of this expertise and expected to use it when appropriate?

- Have hospital personnel been trained in methods of communicating bad news, discerning patient and family wishes and concerns, and respecting dignity through their language and other behavior?

- What structures and processes—for example, ethics committees—are in place to prevent, moderate, or mediate conflicts among clinicians, families, payers, and others?

- What care options are available for dying patients within the hospital, for example, a designated area of palliative care beds governed by different rules regarding visiting hours and other matters for dying patients? Do explicit criteria and processes guide decisions about the use of these options, and are relevant staff throughout the hospital aware of them? Can hospital procedures and the physical environment be modified in other ways (e.g., in the ICU) to reduce stress and discomfort for patients and families?

- Are ICU staff, specialty services, and other personnel trained to recognize patients (and families) for whom the goals of curative or life-prolonging care should be reconsidered with particular attention to the goals of physical and emotional comfort and symptom relief? Are proce-

- dures in place for arranging appropriate care and consultations? Are the important roles of nurses, social workers, and others recognized and supported?

- What structures and processes are in place to help patients and families with transitions to or from the hospital and other care settings? What relationships exist with nursing homes, home care agencies, hospices, and other organizations that care for or assist dying patients? What effort has been made to identify community resources, such as bereavement support groups, and to deliver information on these resources to patients and families?

- What clinical practice guidelines, symptom assessment protocols, and other tools are in place to guide clinical evaluation and care for different kinds of patients who have a high probability of dying (e.g., the very frail elderly with acute illness, victims of catastrophic accidents)? Have practices for foregoing or withdrawing life-supporting technologies (e.g., mechanical ventilators) been reviewed to determine whether they can be modified to reduce distress for patients, families, and staff?

- Are clinical information systems in place that reliably document and update advance planning decisions, symptom assessments, care processes, patient responses, and similar matters? Do they provide clinical decision support in the form of easy access to guidelines, prescribing protocols, and other information relevant to symptom prevention and relief?

- What structures and processes are in place to evaluate and improve the quality of care provided to dying patients? How is accountability for such care managed? Is information about quality of end-of-life care available to the public?

The committee assumes that every hospital will find areas in which its practices can be improved, but differences among hospitals make it unlikely that any single model of end-of-life care can be sensibly recommended or imposed. Hospitals that routinely care for dying patients may be large or small, financially secure or precarious, well or ineptly managed. Depending on their location in suburban, urban, or rural areas, they may experience difficulties in recruiting well-trained medical, nursing, and other personnel. Some hospitals are highly specialized and relatively impersonal, whereas others provide routine acute medical care with a more personal character. The latter may or may not have academic connections, including residency and research programs and consultation links. All face financial constraints or pressures in the form of Medicare reimbursement practices, managed care contracting and payment mechanisms, state and local budget cutbacks, shareholder expectations for for-profit organizations, and increasing numbers of uninsured Americans. (Chapter 6 looks at financing issues in more detail.)

Notwithstanding this variability, the message of this report is that each hospital should be held accountable for identifying its shortcomings and devising strategies to improve the quality and consistency of care at the end of life. The same holds for other organizations and settings of care.

Nursing Homes

The care of dying patients will be an increasingly important issue for nursing homes in future years as the number of older people most at risk for nursing home admission grows and as hospitals and managed care plans continue to minimize hospital stays. Home care agencies, however, are caring for some patients who might previously have been admitted to nursing homes, although the extent to which home care substitutes for inpatient care is debated and the growing cost of home care is creating increasing concern (see the discussion later in this chapter).

Between 1985 and 1995, the number of nursing home residents grew almost 4 percent to about 1.5 million people, but the number of residents per 1,000 people age 65 and over dropped (Strahan, 1997). The number of nursing facilities declined by over 12 percent. The total number of beds increased by about 9 percent but the number of beds per 1,000 population dropped. About two-thirds of nursing homes are for-profit organizations, many of them part of national or regional chains. About two-thirds of nursing homes are certified by both Medicare and Medicaid, and only 4 percent are not certified by either. The large number of facilities (around 16,000 in 1995) and, to some degree, their relative isolation from both the rest of the health care system and the community present some particular difficulties for quality monitoring and improvement.

During the 1970s and 1980s, an increasing amount of attention was directed to the quality of care in nursing homes and the integrity of nursing home management (IOM, 1986; Kane and Caplan, 1990). One result was the 1987 Nursing Home Reform Act, which set forth a variety of regulatory requirements and directions for improvement in nursing home care and management. Care for nursing home residents approaching death was not a major issue during this period. Rather, the focus was primarily on eliminating neglect and mistreatment, preventing physical and mental deterioration and restoring function to the degree possible, and respecting patient dignity and autonomy. As nursing homes attempt to market specialized services or units for care of Alzheimer's, postsurgery, and other patients, the mix of objectives and services will change from the more traditional emphasis of many facilities on generalized long-term care. How these changes might encourage or complicate improvements in end-of-life care is unclear.

Nursing home residents are, altogether, a heterogeneous group. For some patients admitted to nursing homes, death is expected within a rela-

tively short period. Others spend years in a nursing home before their final decline. Many residents are more robust than suggested by common images of frail, bed-bound human beings who are practically at death's door (Caplan, 1990). The committee believes, however, that it is essential to direct more explicit and open attention to the manner of dying in nursing homes and the ways in which care can be improved for dying patients (McCullough and Wilson, 1995; Parkin, 1996; Tolle, 1996b).

One might expect that nursing homes would be well prepared to care for dying patients. Their residents are virtually always functionally impaired. Most require attentive personal nursing care involving oral hygiene, skin care, bowel and bladder care, and nutrition. Some may be anxious, depressed, or fearful. Most who enter a nursing home and stay for more than a few months will die there or after transfer to a hospital. They will not again live at home.

Nursing homes differ from hospitals in many respects, including the low level of physician involvement, relatively low ratios of registered nurses to patients/residents, and the amount of care that is provided by nursing assistants or aides (IOM, 1996c). Staff may not be trained in caring for dying patients and may not provide adequate palliative care, sometimes because physician medication and other orders are not flexible enough. As a matter of routine or as an accommodation to a home's limited resources, residents may be transferred to hospitals, and thus, their dying hours or days are spent in an unfamiliar place with unfamiliar people.

Although nursing homes have been criticized as too often "neither homelike nor known for their quality of nursing care" (Aroskar, 1990), the experience of nursing home patients who die is not well documented. As has been found for other patients, those in nursing homes often suffer from inadequate pain management (Ferrell et al., 1990; Sengstaken and King, 1993; Morley et al., 1995; Wagner et al., 1996).

One analysis by the Washington Home and Hospice found that for the 108 patients who died in its long-term care section, the average length of stay before death was 3.4 years but the range was from 4 days to 30 years (Cobbs and Barry, 1996). The most frequent cause of death was pneumonia. Cancer caused 17 percent of the deaths among the nursing home patients compared to 50 percent in the hospice and home care groups. Only five of the nursing home deaths were considered unexpected. About 60 percent of patients who died required pain medication (usually morphine), and about 12 percent were transferred to the hospital around the time of death. All the patients had documented advance directives.

More descriptive analyses of the experiences of nursing home patients who die would be useful in better understanding care in this setting and identifying its strengths and limitations for different categories of patients/

residents. Questions to be asked about end-of-life care in nursing homes parallel in some respects those for hospitals. They include:

- How well are patients/residents and families informed about who is responsible for care, what they can expect, and who they can look to for information and assistance? What structures and processes are in place to prevent, moderate, or mediate conflicts between clinicians and families?

- How specifically are the preferences and circumstances of residents and families determined, assessed, recorded, and accommodated? Do formal protocols exist for advance care planning, developing physician orders related to life-sustaining treatments, and assuring this information is available when needed? How is this information shared with paramedics and hospital staff if transfers become necessary?

- What practice guidelines, symptom assessment protocols, and other tools are used to guide patient assessment and care? Do they cover the basics of supportive care, including appropriate hydration; nutrition; skin and mouth care; and care for pain, shortness of breath, anxiety, depression, and other symptoms?

- What structures and processes are in place to evaluate and improve the quality of care provided to dying patients? Have practices for patient transfer, communication about changes in patient status or withdrawal of life-supporting technologies, and other decisionmaking been reviewed to determine whether they contribute to avoidable distress for patients, families, and staff?

- How adequate is physician and nursing support for patient care? What education and training related to end-of-life care are available to nursing home staff including all who have contact with patients and families?

- What internal palliative care expertise is available to guide physical, psychological, spiritual, and practical caring for dying patients and those close to them? Are staff routinely educated about the availability of this expertise and expected to use it as appropriate? What relationships exist with external sources of consultation and assistance?

- Are those patients perceived to be dying segregated from other patients? If so, why and with what consequences?

Testimony presented to the committee indicated that nursing home and other long-term care organizations are "deeply challenged" by end-of-life care and decisions and that even "natural death" can be an occasion for sorrow and anxiety (Parkin, 1996). Staff may be uncertain about what the law requires or permits, what religious practices need to considered (especially if the facility is sponsored by a single religious group), what clinical and nonclinical caring is needed and appropriate, the extent to which a

resident is competent to participate in decisions, and how to handle disagreements. The spiritual dimensions of caring may be neglected.

These issues are more systems rather than individual issues, and they need attention at the systems level. Moreover, "an informed corporate conscience" is needed (Parkin, 1996). Ethics committees are helpful, but more than ethical problems are involved.

Home Care

Home Care with Hospice

In the United States, hospice care is usually intended to help people die comfortably at home, although inpatient care and inpatient hospice programs have a role (see generally, Zimmerman, 1986; Mor, 1987; Buckingham, 1996). Hospice-like services and palliative care may be provided by a wide variety of organizations—hospitals, nursing homes, physician groups, HMOs—that are not officially certified. Some do not designate themselves as hospices. Most care for adults, especially cancer patients. A few programs, often associated with inpatient pediatric services, focus on specialized care for dying children, a small but clinically and psychosocially complex group (Martinson, 1978; Howell, 1993; Wass and Neimeyer, 1995; Buckingham, 1996).

In 1996, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) estimated that there were about 1,100 hospices (Singh et al., 1996). For 1994, the Health Care Financing Association reported 1,682 Medicare-certified U.S. hospices. The National Hospice Organization (NHO, 1996a) reports that it "has knowledge of" 2,800 operational or planned hospices (2,200 are members of the NHO). The higher numbers include hospice units that are part of hospitals, nursing homes, and home health agencies. Hospices may be independent organizations (about 30 percent according to NHO, 1996a) or may be organizationally affiliated with home care agencies (22 percent), hospitals (28 percent), or larger integrated health systems. Ninety percent of hospices are owned by not-for-profit organizations, but ownership by for-profit organizations is growing (from about 3 percent in 1992 to 7 percent in 1996) (Singh et al., 1996).

Hospices—as organizations concerned exclusively with dying patients and those close to them—are intended to provide workable and reliable structures and procedures for turning palliative care principles into practice. For example, hospices should back up their commitment to "be there" for patients by

- being accessible to patients and families 24 hours a day, 7 days a

- week, in a sense reproducing on an outpatient basis one of the potential advantage of inpatient care;

- constructing interdisciplinary teams that, taken together, have the necessary knowledge and skills needed to provide comprehensive and continuous care; and

- developing organizational procedures, interpersonal strategies, and care protocols to guide the provision of services in response to common physical, emotional, spiritual, and practical problems faced by patients and their families.

Because hospice programs are designed specifically for dying patients and those close to them, some of the questions relevant to hospitals and nursing homes are not directly relevant. Nonetheless, questions can be asked about how hospice care is organized and managed to fulfill the commitments outlined above. These questions include

- How well are patients and families informed about who is responsible for care, what they can expect, and who they can look to for information and assistance? How are the preferences of patients and families assessed, recorded, and accommodated?

- What practice guidelines, symptom assessment protocols, and other tools are used to guide patient assessment and care? What structures and processes are in place to evaluate and improve the quality of care? What are the criteria for admitting patients?

- What internal and external resources and expertise are available to provide 24-hour coverage, physical and emotional care, spiritual support and counseling, practical assistance, and other aid for patients and families associated with hospice care? What education and training related to end-of-life-care are available to hospice personnel?

- If home hospice care proves insufficient for a patient's needs, what are the arrangements for hospital or nursing home care?

- How is physician support for patient care organized? Are patients' personal physicians encouraged to continue with patients after enrollment in hospice?

- What structures and processes are in place to prevent, moderate, or mediate conflicts involving families, patients, or staff?

In their 1987 book, Mor and Masterson-Allen concluded from their survey of the literature that the typical hospice patient: had cancer; was white, about 65 years old, seriously functionally impaired, and close to death; and had very strong informal support. The committee found no evidence that the typical hospice patient is strikingly different today, although pediatric and noncancer patients are becoming somewhat more

common. Data from the 1993 National Home Care and Hospice Survey found that 71 percent of hospice patients were aged 65 or over, 78 percent were white, over half were married, and the first diagnosis was cancer for 70 percent of patients (Singh et al., 1996).

These data are in part a reflection of the emphasis by early hospice advocates and providers on cancer patients. In part, they are a function of the Medicare benefit, in particular, its provision that death be expected within six months. This provision, which is more applicable to cancer patients than to those with many other diagnoses, is one manifestation of a more general objective of limiting total spending on intensive palliative services for those with terminal illnesses (see Chapter 6).

As noted earlier in this report, the designation of someone as terminally ill and likely to benefit from primarily symptom-oriented rather than life-prolonging care is more difficult for some diseases than others. NHO has attempted to provide guidance for hospices regarding when patients with noncancer diagnoses might be identified as likely to have six months or less to live (NHO, 1996a; see Appendix F). Beyond its particular prognostic focus, this exercise may also encourage more consideration of how patients with noncancer diagnoses can benefit from better palliative and supportive care over the course of their less predictable and often more extended incurable illnesses. Even more broadly, this kind of work may contribute to improved care for those with serious chronic illness who are not considered to be dying.

Early studies comparing hospice and nonhospice care did not find as much difference in symptom control as advocates might have expected, although the difficulty of conducting research and the variability of research settings and designs have complicated comparisons. In their review of the literature, Morand (1987) concluded that "available data show that hospice clearly does not result in patients experiencing increased pain… [and] some comparisons report that hospice may achieve small but significant differences in pain control" (p. 140). They reach similar cautious conclusions about the mixed findings of research on hospice effects on other symptoms, psychosocial variables, and bereavement. Mor concluded that "hospice appears to deliver the kind of service that patients and their families want…[so] they appear to be satisfied with it and have fewer regrets about the orientation of the care received than do nonhospice patients" (p. 156). An analysis undertaken after the authors' literature review suggested that traditional measures were not sensitive enough to reveal any special effects of hospice care so a "quality of dying" measure was devised to assess what patients wanted during their last three days of life (as reported by the principal caregiver) (Wallston et al., 1988). The researchers concluded that patients receiving hospice care were more likely than conventional care patients to die in a way consistent with their desires (in

particular, being free from pain and being able to stay at home as long as desired).

Perhaps because hospice programs are now generally accepted as a desirable option for patients and families who desire it, comparisons of hospice and other care do not appear to be a research priority. It is reasonable, nonetheless, both to encourage a better understanding of the strengths and limitations of hospice care and to support further research on particular processes of care—in any setting—that contribute to patient and family well-being. Relatedly, because fewer than 20 percent of those who die each year are enrolled in hospice programs, more needs to be learned about the needs and circumstances of those not enrolled.

Home Care without Hospice

Home care through alternative arrangements is important for people who do not qualify either for inpatient care or for hospice programs. This latter group includes many people with serious chronic illness (e.g., congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) who may not be perceived as dying, although they are recognized as having an illness that will likely end in death. Many eventually will die in hospitals or nursing homes rather than at home.

Overall, home care involves a mix of people receiving short-term care (e.g., after surgery) and long-term care.4 About two-thirds of those characterized as consumers of home-and-community-based long-term care are cared for entirely by informal caregivers who are primarily female (Hing and Bloom, 1990; Pepper Commission, 1990). (Family care has been described as a "euphemism for wives and daughters" [Holstein and Cole, 1995, p. 171]). About 14 percent of home care patients are cared for solely by formal caregivers, and the rest receive a mix of formal and informal care. For Medicare beneficiaries, use of formal home care has been growing rapidly (Bishop and Skwara, 1993). The number of home care visits grew from 37.7 million in 1988 to 208.6 million in 1994 while the number of persons served per 1,000 enrollees grew from 49 in 1988 to 93 in 1994 (HCFA, 1996b).

In 1996, the NCHS estimated that there were 9,800 home health care agencies, about 80 percent of which were certified by Medicare or Medicaid, usually by both (Singh et al., 1996). Another estimate put the number

of agencies at 14,000 (NAHC, 1993). About 4,000 home care agencies are certified by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (one of two national certifying organizations).

Another option for keeping people at home involves the use of day care services designed specifically for people who are able (with or without special assistance) to leave their homes for supportive care. In addition, people unable to live independently or with families may be cared for in residential board and care homes. Studies have found from 18,000 to 65,000 such homes, some of which are licensed, others not (IOM, 1996a). The involvement of these settings in care at the end of life is largely unknown.

The quality and availability of home care services can reduce the distress, dysfunction, and family stress for many whose trajectory toward death is unpredictable or marked by relative stability punctuated by occasional crises, which may or may not prove fatal (Thorpe, 1993). Patients may develop a strong attachment to home care nurses and other personnel, although frequent discontinuity of personnel is a problem. More generally, the quality and cost-effectiveness of home health care are continuing concerns (see, e.g., Perrin et al., 1993; Kane et al., 1994; Shortell, Gillies, et al., 1994; IOM, 1996a). Quality concerns focus on such issues as

- the training, skills, oversight, and even honesty of paraprofessional personnel;

- the adequacy of attention to symptom relief, psychological problems, and family circumstances;

- the high levels of personnel turnover;

- the management capacities and integrity of agencies including those that provide contract personnel;

- liability for negligence;

- needs assessment and referral to higher levels of care; and

- effective regulation and accreditation strategies.

The committee noted these quality issues with concern. Although it did not locate analyses focused specifically on patients approaching death at home without benefit of formal hospice care, it expects that their experience is quite variable. Some may receive good palliative care, whereas others may receive care that is inattentive to their symptoms and emotional needs. The debate about the cost-effectiveness of home care in averting nursing home or hospital use is reviewed in Chapter 6. For end-of-life care at home without hospice, questions generally should raise the issues noted in earlier sections for both home hospice care and nursing home care.

Coordinating Care Within and Across Settings

Seriously ill patients often move among many different health care settings where they are cared for by many different physicians, nurses, and other personnel. Coordinating care among various personnel and units within a single setting can be difficult enough. Coordinating care during transitions from one setting to another presents even greater challenges, especially when different organizations and funding sources are involved.

Procedures to Smooth Transitions

Because coordination and continuity of care are well-recognized trouble spots for health care organizations, hospitals, nursing homes, and other institutions, a variety of structures and processes have been created to smooth the transition of patients into and out of their organizations. Such structures and processes usually figure prominently in the requirements of accrediting organizations. They include the development of defined procedures for patient transfers (e.g., defining why, when, where, how), follow-up mechanisms, and standardized interorganizational relationships among hospitals, home care agencies, nursing homes, hospices, and other organizations that are or should be involved. Formally integrated health care systems, as described earlier, attempt to provide even stronger mechanisms for coordination, including designated primary care providers and integrated patient information systems. The various structures and processes for coordinating care may or may not be organized with particular attention to the needs of dying patients and their families, and this committee was not able to assess their strengths and limitations in this area.

Broader and more intensive community education may help patients, families, and providers become more aware of the range of health care and other resources available to patients approaching death, including those for whom hospital care is not appropriate but who do not qualify for hospice care. These resources may not be narrowly focused on such patients but nonetheless may be valuable, especially if their potential is more explicitly understood and the ways of integrating them into the care processes and transitions are identified. Thus, community groups might develop inventories of resources available to dying patients not only from health care institutions but also from churches, other charitable organizations, support groups, and agencies serving special populations, such as older individuals, children, or people with disabilities.

For example, a statewide task force in Oregon has developed a booklet listing for every county those resources that may be helpful to dying patients and their families (see Appendix C). This initiative has also included intensive efforts to make advance care planning in nursing homes more

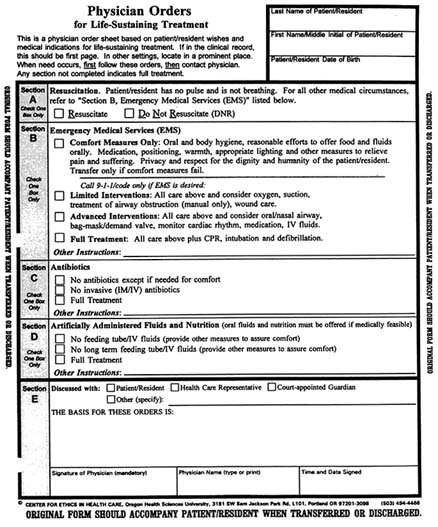

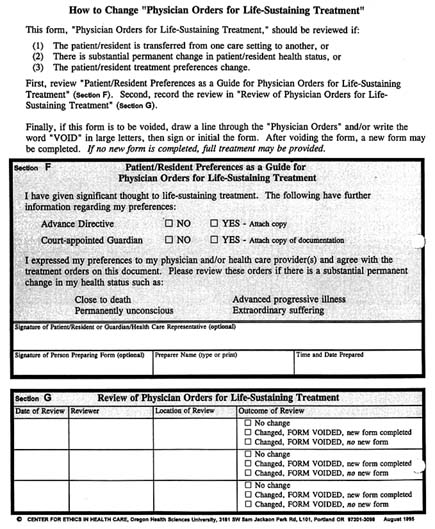

effective so that patients are not hospitalized contrary to their preferences and so that information about patient wishes or surrogate decisionmakers goes with patients when hospitalization is appropriate (Tolle, 1996b). The most visible element of the strategy is a bright pink form that is designed to provide such information clearly but without the expectation that such a form can cover all circumstances. (The form is reproduced—not in color—in an addendum to this chapter.) Accompanying the use of the form is an intensive educational effort intended to reach into every nursing home, hospital, paramedic unit, and similar organization and into homes as well, where the form might be clipped on the refrigerator to be easily located. Although those involved did not feel that their circumstances or resources made a clinical trial possible, they are attempting to collect longitudinal information and data about actual institutional practices that will allow them to assess the effects of the initiative.

Interdisciplinary Palliative Care as a Coordinating Strategy

Interdisciplinary palliative care teams are another way of providing and coordinating different kinds of care. Care teams may play various roles for patients and those close to them, and they may be differently composed and organized in different settings. Patients and families and others involved in caring for patients are considered members of the care team as well as the focal point of the caring process. For some patients, especially hospitalized patients, "formal" members of the care team may be a major presence. For others, particularly those dying at home, the care team may be a helpful but relatively minor and intermittent presence. The care team exists, in any case, to support the patient and family, not to intrude upon their efforts to deal with the personal, social, emotional, philosophical, or spiritual experience of dying.

Home Hospice Teams

A core element of palliative home care is the interdisciplinary care team (Mor, 1987; Hull et al., 1989; Ajemian, 1993; Buckingham, 1996). In addition to health professionals and others, most home hospices stress the need for a family member or someone else who can serve as a primary caregiver for a patient who wants to die at home. Some will not accept patients without a person who can be so designated (NHO, 1996a). Finding a person or persons to serve in that role is difficult but possible for some patients and not possible for others. Hospital-based hospices are more likely to serve patients who live alone or have employed caregivers (Mor, 1987). Some community hospices operate inpatient units that also serve

such patients, and others have arrangements with nursing homes or hospitals.

For hospice organizations, the interdisciplinary team is directly responsible for patient care in the home. The team may also support staff in institutions, such as hospitals and nursing homes, that can provide most or all such care using their own personnel. To be eligible for Medicare payment, a hospice must have an interdisciplinary team that includes at least a physician, registered nurse, social worker, and counselor and must designate a nurse to coordinate care for every patient (HCFA, 1996a). Core nursing, physician, and counseling services must be provided by employees or volunteers. Additional requirements also apply to records, training, and other matters.

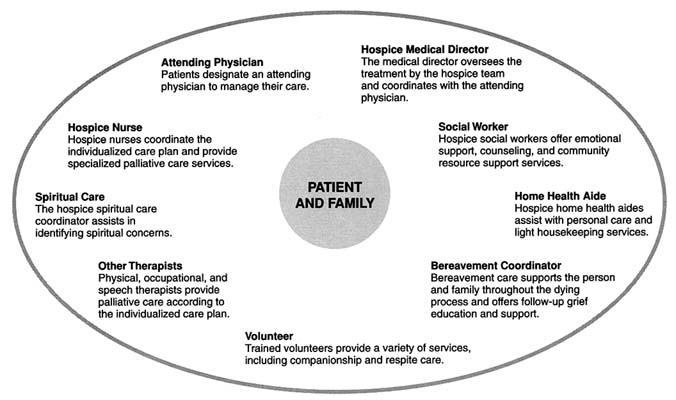

Central to the care team are a nurse and a social worker. The other members of a typical team are depicted in Figure 4.1.

The nurse typically provides services—either directly or by calling on other professionals as needed—to help the patient cope with progressive illness. She or he also acts as case manager, often in tandem with a social worker. The nurse is usually responsible for ongoing assessment of the patient's physical and emotional status, developing a plan of care, working with physicians to adjust medications and other treatments for physical and psychological problems, educating family members about how to avoid problems (e.g., odor) and what to do if a problem (e.g., a seizure) occurs, monitoring family status, arranging additional help as needed, and generally being available to answer questions. The specific nursing care and consultation needed for a dying patient varies depending on the nature and stage of his or her illness.

The social worker typically shares case management responsibilities and helps the patient and family with personal and social problems by providing psychological assessment and counseling, advocating for them with health care providers and others, offering information and help with interpreting information, and assisting with practical matters (Loscalzo and Zabora, 1996). In one report on hospice cancer patients in the United States, about 75 percent of formal supportive counseling was provided by social workers (Coluzzi et al., 1997).

Most hospices employ physicians, nurses, and social workers (and administrative personnel). Less intensively involved personnel may work part-time or on a contract basis. Hospices as a matter of philosophy and tradition (as well as Medicare certification requirements) stress volunteerism.5

Some hospices depend heavily on volunteers or contract personnel instead of employed staff. Volunteers serve in many capacities and are generally screened to match their talents and interests to organizational and patient needs. Some provide the key clinical services while others provide emotional and practical support to patients and families or perform administrative and informational tasks for the hospice.

A hospice patient may stay under the care of his or her personal physician, and many patients and physicians prefer such continuity. Alternatively, the hospice medical director may serve as the patient's attending physician. In the committee's experience, it is sometimes difficult for the personal physician to stay involved if house calls are required. Also, some otherwise excellent physicians may not be comfortable with an established hospice team, and others may not be fully familiar with the principles and techniques of palliative care, including appropriate use of opioids. Even if a patient is transferred to a hospice-based physician for good reasons, the personal physician can stay involved to provide support and information that may be useful for the hospice team. Many patients and families who have had a long-standing relationship with a physician undoubtedly would appreciate further communication, such as a call when death is near and a call or letter afterwards.

Effective teamwork requires active and continuing effort by all team members and by those responsible for overseeing their performance. For palliative care teams, the challenges are many (Ajemian, 1993). Team members come from very different professional backgrounds, which creates the potential for role conflict. Sorting out and maintaining clear responsibilities for decisionmaking, information provision, and other tasks is important if people are to know what is expected of them. Even so, conflict management may still be necessary. Part-time staff and volunteers, however important, can be awkward to fit with an established team, and relationships with others who have cared or are caring for the patient can become strained. For example, if hospice personnel are involved with the care of a long-term nursing home patient, staff at the nursing home may have established a close relationship with that patient and may be upset if their care for the patient is ignored. Coordination is a pervasive and continuing challenge that requires a balance between the time required for coordinating activities and the time devoted to the activities themselves (e.g., caregiving, documentation).

Inpatient Palliative Care Teams

Clearly identifiable inpatient palliative care teams have not been routine for nursing homes or hospitals. Medicare-certified hospices must have an interdisciplinary palliative care team (HCFA, 1996a). The Joint Com-

mission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization's standards for nursing homes call for an interdisciplinary team whose responsibilities include care planning and, by implication, palliative care for those needing pain management and similar care (JCAHO, 1996a). For hospitals, Joint Commission standards refer generally to teamwork and interdisciplinary collaboration but do not explicitly call for an interdisciplinary team in care for dying patients (JCAHO, 1996b).

It is the committee's experience that many hospitals and nursing homes have no personnel with clearly designated palliative care expertise. Hospital ethics committees may help resolve conflicts among patients, families, and clinicians about care goals for gravely ill patients, but this is not equivalent to expertise in symptom prevention and relief or in other aspects of palliative care.

Depending on an institution's objectives and characteristics, the options for developing palliative care expertise include interdisciplinary care and consulting teams or designated individuals who may be called upon to provide or assist with palliative care. The care team may be the option best suited for the varied and complex needs of seriously ill, hospitalized patients, whereas designated personnel and care protocols may be reasonable for nursing homes that can call on outside experts for consultation about more difficult situations including those that might otherwise appear to call for hospitalization.

In some cases, members of a designated hospital-based palliative care team may function less as regular caregivers than as consultants, particularly if the hospital does not have an inpatient palliative care unit (Abrahm et al., 1996). Such a team would typically function in an environment in which a variety of curative, palliative, rehabilitative, and other services are provided and in which very sick patients with many different diagnoses and problems are treated. The members of the team would help physicians and nurses care for patients with refractory pain or other especially difficult problems in symptom prevention and management. In an academic medical center, this kind of palliative care team might consist of one or more physicians, specialist nurses, social workers, pharmacists, and chaplains.

In some environments, other approaches may make sense. For example, one academic health center that served mainly as an emergency and trauma facility for a disadvantaged inner-city population established a supportive care team for hopelessly ill patients (Carlson et al., 1988; Campbell and Frank, 1997). In this case, the team consisted of a clinical nurse specialist and a small, rotating group of physicians.

The availability of a palliative care team should not imply that those routinely caring for dying patients can do without the clinical and interpersonal skills and attitudes needed to prevent and relieve common causes of

distress for dying patients and those close to them. Nurses are central in this regard.

Given the current medical culture, the organization of a palliative care team may reinforce the role of ethics committees and others in helping hospital staff recognize when aggressive diagnostic or life-prolonging interventions are inappropriate and how to communicate sensitively with patients and families to help them focus on what can be done. Members of such a team may also play an important part in undergraduate and graduate medical education and in research to build a stronger knowledge base for end-of-life care. They may provide consulting services to hospice care teams, nursing home staff, and others faced with particularly difficult clinical problems. Educational and research roles of palliative care specialists are discussed further in Chapter 8.

Managed Care as a Coordinating Strategy

As indicated earlier, this report uses the term managed care broadly to refer to organizations that direct patients to a limited panel of health care providers, pay providers in ways that encourage economical use of services, and/or employ administrative and educational mechanisms to control access to expensive services. Although not usually counted among such organizations, hospice is a form of managed care applied to certain terminally ill patients.

Conventional HMOs and managed care arrangements have not yet enrolled a large proportion of the Medicare population overall.6 Nationwide, only 10 percent of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in HMOS. However, in California, Oregon, Arizona, and Hawaii, the figure is over 30 percent, and in some Oregon counties, it is over 40 percent (Zarabozo et al., 1996). Although Medicare enrollment in HMOs under represents those most likely to die (e.g., the oldest old and functionally impaired), an increasing number of older people can be expected to be enrolled in managed care when they die (Zarabozo et al., 1996). A portion of these individuals will, however, be cared for and die in nursing homes, and much of this care will be paid for by private funds or Medicaid. Although state Medicaid programs may be considering managed care for poor, functionally impaired recipients, its feasibility and benefits for most nursing home patients is not clear.

The pros and cons of using conventional managed care to cover people with serious chronic illness have been debated, although little attention has

focused on those considered terminally ill (Schlesinger and Mechanic, 1993; Miles et al., 1995; Jones, 1996a,b; Miles, 1996; Paris, 1996; Post, 1996; Spielman, 1996; Virnig et al., 1996). The federal government has funded a number of social health maintenance organization (SHMO) and other demonstration projects specially designed to improve coordination of care and quality of life for frail elderly people (Vladeck et al., 1993). Research suggests that such plans are more likely to use case managers to monitor patient needs than conventional managed care plans, and they tend to provide somewhat different patterns of care for patients compared with fee-for-service settings (Harrington and Newcomer, 1991). Regardless of the pros and cons of SHMOs, they are not now available to most Medicare beneficiaries with serious chronic illnesses, including terminal illnesses.

Several HMOs, for example, several Kaiser plans, have long operated their own hospices, but most are thought to contract with hospices, as is likely the case for other organizations such as risk-bearing medical groups or integrated health systems. Some managed care organizations have established arrangements for managing the care of seriously ill individuals that closely parallel hospice programs in some respects but that may be more flexible (e.g., not explicitly limited to patients expected to live six months or less) (Blackman, 1995b; Baines, Gendron, et al., 1996; Della Penna, 1996; Emma, 1996). These arrangements may be viewed by organizations as sufficiently valuable on the bases of cost, quality, and patient satisfaction that they are included in their standard benefit package rather than priced separately as an additional benefit.

In comparison to traditional fee-for-service medicine, several positive features have been attributed to managed care (most often cohesive, integrated health plans such as well-established staff- or group-model HMOs). These features—which, if implemented effectively, parallel the model of palliative care—include7

- more attention to preventing medical problems,

- greater continuity of care,

- reduced levels of inappropriate treatment,

- better use of health care teams coordinated by primary care clinicians, and

- coverage of services not included in traditional health insurance.

The usual criticisms of managed care—particularly for people with chronic, progressive, or advanced illnesses—are that

- managed care plans have been designed primarily to serve relatively healthy and younger populations;

- they tend to attract or keep healthier individuals, while those who are less healthy stay with or move back to programs such as traditional Medicare;

- the composition of physician panels and use of other practitioners reflect the composition of the enrolled population and the plan design and thus may not match the needs of chronically ill patients;

- current capitated payment methodologies and a competitive marketplace make it very much in the financial interest of health plans to avoid enrolling patients with serious chronic illness; and

- these same financial incentives encourage underservice.

The information available to the committee primarily involves HMOs and not other forms of managed care, and very little is known specifically about care for those who are dying. Evidence of underservice or poorer outcomes is mostly speculative or anecdotal.

A few studies do, however, reinforce concerns about the effect of some managed care arrangements on people with serious chronic illness (see, e.g., Shaughnessy et al., 1994; Ware et al., 1996a, b; but also Brown et al., 1993). A recent study of a sample of frail elderly Medicare patients in a single integrated health system with both HMO and fee-for-service (FFS) patients concluded that the "HMO studied here served frail enrollees in ways that increased rather than reduced total and preventable hospital readmissions" compared to FFS beneficiaries (Experton, Li, et al., 1996, p. 1). The same researchers also found, in a related analysis, that about the same proportion of HMO and FFS patients used some home health services but that the HMO members who used home health care services received significantly fewer services than FFS members (Experton et al., 1997). The researchers suggested that the HMO should investigate premature hospital discharges and access to post-acute care" (Experton, Ozminkowski, et al., 1996). The study found no difference in total hospital days, emergency room use, or use of skilled nursing or rehabilitation services. Again, these findings are consistent with other research, which suggests possible problems in the treatment of people with serious chronic illness who need further attention from managed care plans, policymakers, and researchers.

In Minnesota, Miles and colleagues indicate that health plans ration the use of hospice care, visiting nurse care, respite care, and spiritual and psychological counseling for end-of-life care (Miles et al., 1995). He notes that such practices are "not unique to end-of-life care" but that their application to those approaching death "promises to be a hot spot" (Miles et al., 1995, p. 304).

More generally, the committee heard some concerns from hospice or-

ganizations about the practices (actual or feared) of managed care organizations. One concern expressed to the committee involved the "micromanagement" by some HMOs of care for non-Medicare patients enrolled in hospice (Murphy, 1996; Tehan, 1996). Practices mentioned included denial of certification for appropriately intensive home care or for appropriate hospitalization for palliative care. Such practices have quality as well as financial implications. They may reflect that newer managed care organizations serving mainly younger patients are unfamiliar with hospice. Thus, just as those in fee-for-service medicine may need education about palliative care and hospice programs, so may those in managed care.

Revisiting the Care System at the Community and National Levels

The concerns raised earlier in this chapter and the promise of initiatives such as those described in this report led the committee to consider characteristics of community care systems that would more effectively and reliably serve dying patients and their families. Such systems would offer comprehensive community health care and other resources that would permit greater integration of care across settings and more flexibility for patients, families, and clinicians. As depicted in Box 4.1, "whole-community" approaches to end-of-life care would draw on the medical and nonmedical approaches to care described in Chapter 3. They would also accommodate patients with unusual conditions and circumstances as well as those with more typical situations. The aspirations of whole-community approaches to care at the end of life include:

- making palliative care available wherever and whenever the dying patient is cared for;

- promoting timely referral to hospice for patients whose medical problems and personal circumstances make hospice care feasible and desirable;

- allowing more flexible arrangements for patients whose prognosis is less predictable but for whom palliative services would be valuable in preventing and relieving symptoms and discouraging unwanted or inappropriate life-prolonging interventions;

- encouraging, when possible, the continued involvement of personal physicians after patients' referral to hospice;

- promoting fuller and more sensitive discussion of diagnosis, prognosis, and care objectives; and, by taking these steps,

- helping dying patients and their families to plan ahead and prepare for dying and death.

|

BOX 4.1 A Whole-Community Model for Care at the End of Life

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The component resources of an ideal system to serve these objectives would include a mix of organizations, programs, settings, personnel, procedures, and policies. A system with these components would reflect the understanding that there is not just one way to care for dying patients. The people, tools, and other resources would need to be available in many settings and be flexible enough to respond to patients who do not comfortably fit the routines and standards that serve most patients well.

Clearly, the elements of such a whole community system represent an aspiration. The difficulties faced by those seeking to improve care at the end of life will vary from community to community, and some elements may be easier to achieve than others. Overall, however, this model implies effort on multiple levels—within individual health care and other organizations and government agencies and through cooperative community, regional, and national initiatives.

Conclusion

Desirable and obtainable care for those approaching death is determined by both individual and system characteristics and their interactions. The individual's disease, clinical status, emotional state, and preferences determine much about what clinical care is appropriate. Personal values, financial circumstances, family structure, and other patient or family characteristics set limits on what is possible or, at least, what is more or less difficult to accomplish.