6

Key Lessons and Priorities for the United States

WHAT HAS CHANGED AND WHAT HASN'T?

From examination of the historical context for technology and economic development in the United States and Japan and recent trends at the national and industry levels, the Competitiveness Task Force identified major areas in which important changes have occurred or are occurring, and others where earlier patterns are likely to persist. Table 6-1 summarizes the task force's judgments.

Issues for Japan

Barriers to Participation in the Japanese Market and Impacts

Japanese government and industry no longer exercise the most potent policy tools to extract technology from foreign companies as a price of market entry, particularly control over trade and foreign direct investment. Overall, progress toward more open markets in Japan has accelerated in recent years, particularly consumer markets, as appreciation of the yen and other factors opened a significant value gap between goods produced in Japan and those produced abroad for many industries. Many U.S.-based and other foreign companies are taking advantage of new opportunities to expand market participation.1

Although the trend is moving in the right direction, the pace and degree of market opening vary widely depending on the industry. Particularly in critical sectors where sales are made to companies rather than consumers, such as automotive components and semiconductor manufacturing equipment, market barriers are still an issue. In some industries the Japanese policy environment in regulation, competition policy, intellectual property protection, and other areas still serves to prevent U.S.-based companies from fully participating in the Japanese market. Much of the rise in Japan's manufactured imports has been due to products manufactured in Asia by Japanese firms.

However, in the opinion of the task force, Japan's closed markets in high-technology industries where innovation is occurring most rapidly have stunted competition and innovation. In areas where the domestic market is protected and does not drive competition and innovation, barriers to foreign and domestic entrants may do more harm to Japanese industry than to U.S. and other foreign-based competitors.

Impact of New Players

The rapid growth of Asian economies and the emergence of Asian companies as important new players in high-technology development and manufacturing will have a significant impact on

TABLE 6-1 Evolution of U.S.-Japan Science and Technology Relations and U.S. Competitiveness

|

|

Past |

Present |

Future |

|

Scientific and Technological Capabilities |

• The United States was preeminent in most areas, driven by defense needs. • Japan's capabilities expanded rapidly, particularly in applied fields linked to growing industries. |

• US. capabilities remain formidable, with focus on commercialization and diffusion; improvement spurred by Japanese competition. • Japan has reached parity or near parity in many key fields but capabilities are unbalanced; investment in nonproprietary R&D by government has been low. |

• Japan follows through on goal to significantly increase public spending on basic R&D, exceeding US. per capita spending. • The U.S. R&D enterprise restructured to fit post-Cold War and budget balance realities. • Both countries refine approaches to public-private partnerships and international cooperation. |

|

Policy and Corporate Strategy Focus |

• For Japan: catch up/reduce dependence through technology acquisition, target resources to manufacturing industries, • For the United States: maintain defense technology lead; maintain strong basic science and research base; consumer-focused economy. |

For Japan: develop greater strength in fundamental research; globalize corporate technology capabilities; new policy approaches to catch up in information For the United States: reinvigorate manufacturing; greater market and global focus for companies. |

• For Japan: defensive and protective action increasing as new competition emerges in Asia? • For the United States : pursue global IPR protection to ensure returns on R&D investment; more aggressive trade policies? |

|

|

Past |

Present |

Future |

|

US-Japan Science and Technology Transfer Relationship |

• The relationship has been one-sided, with science and technology knowledge flowing predominately to Japan. • Barriers to trade and investment were effective tools for Japan in facilitating technology acquisition. The United States was not prepared to access Japanese technology. |

• Bilateral technology flow is still unequal, but patterns and balances have changed. • Japan has less scope to use market access barriers to acquire key U.S. technologies. Effectiveness of new mechanisms uncertain (sponsoring U.S. university research, launching foreign R&D laboratories). • The United States has developed limited capabilities to access Japanese technology. |

• Bilateral flows of technology remain uneven, but more partnerships will be characterized by comparable contributions. • Renewed Japanese investment (mainly in information sectors) in foreign R&D reflects an expectation that new mechanisms will pay off. • U.S. opportunities to access Japanese technology will depend on market access and the level of scientific and engineering research sone in nonproprietary settings. |

|

Competitiveness Impact and Situation |

• Technologies transferred from abroad were a key ingredient in japan's rapid ascent as a techno-industrial superpower. • Japanese firms took advantage of U.S. complacency. |

• Japanese competition has benefitted U.S. companies and industries; the United States has adapted Japanese management, employee relations and partnership strategies. Japanese competitiveness gains vis-á-vis the United States have slowed and in some cases been modestly reversed. |

• U.S.-Japan competition will be affected by new players , especially in Asia. • Information industries will continue to be a key area for U.S.-Japan cooperation and competition. • U.S. gains are real and sustainable, but complacency and renewed efforts by Japanese government and industry will pose challenges. |

the U.S.-Japan relationship. Technology investments and technological capabilities are growing rapidly across Asia. Both U.S. and Japanese companies face challenges as they try to access Asian markets while managing the risks of creating future competitors through technology and production transfers. There is evidence that they are taking different approaches. In the automobile industry, for example, suppliers of Japanese automakers are inclined to invest as a coordinated group, while U.S. companies are not. Although their ultimate impact can be debated, the task force believes that Japanese government and industry economic strategies toward Asia are much more systematic and coordinated than are those of the United States.

Scientific and technological relations with Asian countries, including competition and cooperation with Japan in a broader Asian context, will increasingly affect U.S. and Japanese innovation capabilities. There are several contrasting visions for the future. According to one, Japanese companies and government are pursuing a coordinated strategy to achieve a preeminent position in a number of emerging Asian markets. If they are successful in establishing a Japan dominated Asian manufacturing and market base from which competitively priced manufactured goods flow to the rest of the world and which largely excludes non-Japanese foreign influences, this would expand and extend Japan's ongoing economic imbalances with the rest of the world to an Asian problem.

According to another formulation, whatever strategies Japanese companies and government are pursuing, it will be difficult for them to dominate the emerging Asian economic powerhouse. Growing Asian technological and manufacturing capabilities will create greater competition for Japan-based firms in a number of areas. This trend has already benefited the U.S. electronics industry, as Asian production networks broke the stranglehold of Japanese companies in the supply of a number of critical components, depriving the Japanese industry of leverage with which to compete with U.S. leaders in higher-value-added areas.

Japanese Responses

Japanese industry and government are responding to these challenges in a number of ways. In automobiles, semiconductors, and other manufacturing industries, Japanese companies have moved many manufacturing activities to Asia, the United States, and elsewhere and have redoubled continuous improvement efforts to ensure that critical manufacturing tasks can be performed in Japan at competitive costs while recognizing flat domestic demand and possible broad swings in exchange rates. Japanese companies continue to aggressively pursue global markets in industries where they have experienced failure in the past, such as personal computers. Although Japanese companies have less ability to invest in long-term research and other capabilities than was the case during the bubble years, corporate governance and financial systems still appear to allow a longer-term view than is typically true of U.S. companies.

Japanese companies are continuing to develop new approaches to tap foreign technological capabilities. For example, 1995 saw a renewed interest in Japanese investments in U.S. R&D facilities, particularly in information industries. In biotechnology, Japanese companies have invested in partnerships with small U.S. biotechnology firms to build their in-house capabilities and utilize biotechnology as an avenue to compete in global health care and agriculture markets. Experts point out that Japanese research capabilities and technological sophistication in this area, both in research institutes and in companies, has grown considerably over the past decade.

In addition to the competitive responses of companies, Japanese government and industry are attempting several systemic changes to bolster national capabilities in fundamental research and new technology-based industries. The Science and Technology Basic Law of 1995 and the Science and Technology Basic Plan of 1996 call for large increases in public spending on

research and development and institutional reforms to create a research environment more conducive to fundamental work. In critical industries such as semiconductors, government and industry have launched new national technology development programs to boost long-term competitiveness. Some limited steps also have been taken to increase incentives for investing in technology-based start-up companies. Although the results of these changes are not certain, taken together they represent a significant and focused national effort to maintain Japan's place at the forefront of global high-technology industries.

Issues for the United States

Narrowing but Persistent Manufacturing and Product Development Gaps

U.S. companies in a range of industries have clearly responded to the challenge of Japanese competition over the past decade. This has contributed to the improved competitiveness of the U.S. economy as a whole. In the automobile industry, for example, this has involved improved performance in both manufacturing and product development to close the gap with Japanese companies. As a nation, the United States has pursued a successful decentralized effort over the past decade to better understand Japan and pursue effective interactions. However, in automobiles, semiconductor devices, and other manufacturing industries, Japan still has a manufacturing edge.2 U.S. manufacturers, including Japan-based companies manufacturing in the United States, will need to continue to improve in order to avoid falling significantly behind the Japanese and in some cases Asian economies in the future.

In the opinion of the task force, how well the United States addresses fundamental challenges such as improving K-12 education and raising savings rates—issues outside the scope of this report—will play a large part in determining whether the U.S. economy will continue to make progress in manufacturing performance and competitiveness.

Continued Strength in Fundamental Research, With Future Uncertainties

Much of the U.S. industrial and competitive resurgence of recent years has been based on continued strength in fundamental research and market-driven innovations. The United States still produces the lion's share of technological innovations with significant commercial implications and remains the premier location for research and innovation.

Concerns have been raised that Japanese and other foreign companies are siphoning U.S. innovations through investment in U.S. high-technology companies, links with U.S. universities, and establishing U.S. R&D laboratories.3 The flip side of this concern is the fact that these investments demonstrate, and to some extent enhance, continued U.S. strength in fundamental and applied research.4 At this point, it is difficult to assess in a general way how these investments have affected the Japanese investors and U.S. capability to innovate. Based on the

|

2 |

See automobile and semiconductor equipment industry cases in Chapter 5. On autos, see "Big 3 Post Quality Gains, Japanese Still Lead," Reuters-Yahoo News, May 1, 1997. |

|

3 |

See Linda M. Spencer, Unencumbered Access: Foreign Investment in the United States (Washington, D.C.: Economic Strategy Institute, 1991), and Linda M. Spencer, Foreign Acquisitions of U.S. High Technology Companies Database Report: October 1988-December 1993 (Washington, D.C.: Economic Strategy Institute, March 1994). |

|

4 |

National Academy of Engineering, Foreign Participation in US. Research and Development (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1996). |

anecdotal information available, the task force believes that these investments have constituted a net benefit for U.S. innovation.5

However, the future is unclear. While Japan has announced plans to increase public support for fundamental research, in the United States both major parties are committed to balancing the budget, and debate continues over the post-Cold War rationale for government support for science and technology. In particular, some aspects of the federal government's role in science and technology development aimed at improving U.S. economic performance remains a subject of intense debate. The task force believes that this debate cannot be allowed to impair the U.S. research base.

Strength in Information Industries and Market-Driven Innovations

Another U.S. strength is its dynamic competitive market, which spurs companies to rapidly create new products and applications. The primary current example of this strength is in computers, software, and related information industry sectors. The overall level of U.S. industrial R&D spending has been relatively flat over the past decade, although investments have been growing recently. Some decry the R&D restructuring that has gone on in the industrial labs of large U.S. companies and assert that lower industry spending on R&D with medium-and longer-term payoffs will harm these companies and the United States in coming years. Others applaud the renewed focus of U.S. companies on immediate customer needs, time to market, and short term product development performance. There is evidence that U.S. companies are once again increasing longer-term R&D spending as they are able to sustain profitability.6 The most successful companies are increasing their own R&D investments and utilizing more basic research results generated by U.S. universities and government laboratories.7

In addition to trends in overall spending, there has been a shift in the industry sectors performing R&D. In recent years nonmanufacturing industries, such as software and high technology services such as telecommunications and information systems consulting, have expanded their share of overall U.S. R&D spending. In these areas the United States is investing in the technology necessary to lead innovation in the high-growth industries of the future. However, the task force had concerns over whether investments in other fundamental areas (such as advanced materials) are adequate to maintain U.S. technology and manufacturing. It is not sufficient to judge R&D expenditures in the aggregate. More detailed analyses by industry sector and discipline will be necessary to guide policymaking.

Challenges of Continued Globalization

Although the best U.S. companies appear to be well positioned to compete in the twenty-first century on the basis of superior technology and global vision, questions can be raised over whether the United States will remain an attractive location for manufacturing and innovation and whether U.S. companies will develop capabilities to access an emerging global science and technology base. As companies, universities, and other organizations take their own approaches

to globalization, the United States will continue to find it difficult to develop a national approach to international science and technology relationships. In particular, the growing strength of laboratories, human resources, and universities outside the United States, particularly those of Japan and other Asian countries, will enable these countries to approach U.S. capabilities in all phases of research and innovation.

PRIORITIES AND POLICY OPTIONS FOR THE UNITED STATES

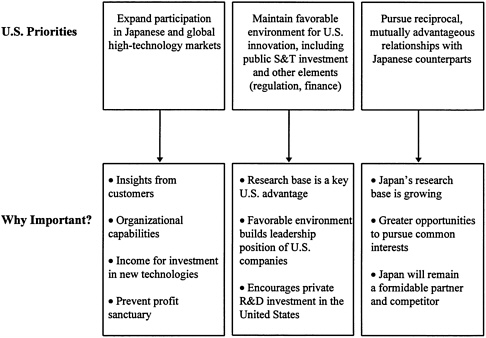

In light of these trends, what should be the priorities of the U.S. public and private sectors as they seek to maximize U.S. competitiveness interests in science and technology relations with Japan? This section links the broad national interest of sustaining and expanding high-wage employment in the United States with several enabling conditions related to U.S.-Japan science and technology relations, specific tasks, and supporting policies. Figure 6-1 summarizes the priorities and rationale for each.8

FIGURE 6-1 U.S. priorities for maximizing economic benefits to U.S. citizens from science and technology relations with Japan.

Building U.S. Capabilities to Access and Utilize Japanese Science and Technology

Over a number of years the United States has pursued a variety of efforts to build a stronger base of knowledge and expertise in Japanese science and technology. Several public-sector efforts have been undertaken within the framework of the U.S.-Japan Agreement on Cooperation in Research and Development in Science and Technology (U.S.-Japan S&T Agreement) and other agency-specific agreements.9 Although it is difficult to directly measure the impacts on U.S. innovation capabilities and competitiveness, the task force's overall assessment is that these are well-leveraged, necessary investments that should be continued. These capabilities include (1) a group of U.S. scientists and engineers proficient in the Japanese language, with firsthand experience in Japanese R&D and manufacturing organizations and practices and (2) capabilities to collect and translate Japanese technical, business, and policy information and make this available to the U.S. private sector, preferably through electronic means. The rationale behind continued public support for these efforts is covered in Chapter 4.

The task force also considered issues related to U.S.-Japan governmental agreements and agency-to-agency cooperative programs. Although most of the important science and technology exchanges that influence economic performance and competitiveness take place in the private sector, the policy framework and official cooperation can be expected to play a more important role in the future. In particular, the task force believes that as Japan increases its fundamental research investments in coming years the United States will need a strong capability to keep track of opportunities for U.S. scientists and engineers to tap into and benefit from these efforts and to ensure they are open.

The U.S.-Japan S&T Agreement is an important component of the policy framework. The task force considered several areas in which U.S. implementation of the agreement might be improved.10 First, as official U.S.-Japan R&D collaboration in areas such as global change, space, health, and other areas expands, the participating U.S. agencies should focus on ensuring that collaboration is effective and mutually beneficial. Increased exchange of information and perspective among U.S. agencies on various aspects of project management within the structure of the U.S.-Japan S&T Agreement would help ensure that new projects have access to an existing knowledge base and would promote greater coordination and cooperation across agencies in developing and managing cooperative programs.

Second, more focus should be placed on tracking the results of official collaboration and the overall science and technology relationship. The U.S.-Japan S&T Agreement specifies several metrics that should be compiled annually for the Joint High-Level Committee, mainly in such areas as personnel exchanges and the domestic R&D programs of each country that are open to participation on the part of the other. The task force believes that developing a simple set of metrics to be compiled each year and made available to the public would allow scientists, engineers, and policymakers to assess progress in the relationship and identify areas where additional efforts are necessary.

The metrics should include scientific and engineering personnel exchanges funded by each government (funding and number of participants for various lengths of stay), public funding of collaborative projects, participation by U.S. companies in Japan's publicly-funded R&D programs (and vice versa), and an inventory of intellectual property created by collaborative

programs. These could be updated annually as part of the administration of the agreement. Perhaps in the future this effort could be linked with Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development efforts to develop better tools for measuring and understanding international science and technology relationships. The task force realizes that some effort and expense are involved in developing these metrics. However, much of the underlying data necessary for developing them is already collected. The main effort would be in reaching agreement on a common basis for compiling and reporting these data. The United States and Japan should take a leadership role in this regard.

Finally, the U.S. public and private sectors should extract appropriate lessons from the experience of dealing with Japan in relationships with other emerging techno-industrial powers. For example, Korea is using many features of the Japanese model of technology-driven economic development, and barriers to market participation by U.S. industry resemble those previously encountered in Japan. Over the long term, China's growing role in the world economy and technological enterprise will pose challenges and opportunities to the United States, Japan, and other developed countries. China's approach to technology acquisition for economic development is likely to feature less central coordination than the Korean and Japanese examples, but this may allow more effective integration of China's science and technology establishment into that of the United States and perhaps other countries. This emerging Sino-U.S. integration will undoubtedly give rise to synergies and mutual benefits but may prove even more challenging to the United States than the relationship with Japan has been in developing a coherent U.S. strategy for pursuing economic, security, and other interests.

Participation in Japanese and Global Markets

The task force believes that market participation is the element in the U.S.-Japan relationship that has the most impact on U.S. capabilities to generate and effectively utilize innovation to create and maintain good jobs for U.S. citizens. Participation in the Japanese market will continue to be critical, and in the future participation in Asian markets will grow relatively more important.

Demanding and Innovative Customers Spur Technology Development

The key contribution that demanding and innovative customers, or lead users, often make to the technology development efforts of individual firms and national industries is well established.11 The importance of customers is perhaps greater for companies serving industrial markets than it is in consumer markets, where suppliers often provide key insights and innovations.

Presence in the Japanese and other advanced country markets spurs technology development at a U.S.-based company in several ways.12 First, through the act of modifying a product to meet the needs of Japanese customers, a company can develop new product features and technologies that are applicable in other markets or even globally.

Second, if a significant part of the global market for a product consists of customers based in Japan, U.S. companies wishing to become or remain competitive must be successful in supplying Japanese firms and meeting their overall requirements for quality and performance, which could be more stringent than the requirements of firms based elsewhere. Corning's experience in

|

11 |

Michael E. Porter, The Competitive Advantage of Nations (New York: Free Press, 1990); Eric A. von Hippel, ''Has Your Customer Already Developed Your Next Product?" Sloan Management Review, Winter 1977. |

|

12 |

Box 5-1 describes a specific example. |

supplying glass for flat panel displays and Rockwell's experience in supplying modem chips to Japanese customers are important examples of this benefit.

Third, participation in Japanese and other technologically sophisticated overseas markets provides a revenue base and helps establish an organizational presence. This presence facilitates the hiring of skilled local personnel, including scientists and engineers, and underwrites overhead for other activities that help establish the U.S. company as a participant in Japan-based technology and market development activities. Such a presence allows a U.S.-based company to learn about and apply technological developments and activities of Japanese suppliers, partners, and competitors faster than would be the case if there was no market presence.

Because of the rapid globalization of markets and international convergence in technological capabilities, it is imperative for firms based in the United States and elsewhere to develop, access, and utilize the world's best technology rapidly at competitive costs. In the past the external insights driving technology development were very likely to come from customers and suppliers of the same nationality. However, globally competitive firms increasingly require access to knowledge from a global customer and supply base.

Expanded Market Participation Provides Resources for Investment in Next-Generation Technology

By raising returns on technology investments, overseas sales provide resources for the development of next-generation products and processes. This is an additional critical link between overseas market participation and U.S. technology development activities. In its dispute with Fuji Film, Kodak alleges that denial of market access in Japan has caused lower levels of investment in new technology in the United States.13

The semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME) industry also provides a good illustration. Leaving aside for a moment the question of what has influenced access to the Japanese market in this industry, it appears that Applied Materials, which has a much greater presence in Japan than many other U.S. SME firms, has grown faster and has access to a much larger revenue base for investment in new technologies as a result of its strong presence in Japan.

Japanese Market Barriers Have Impeded U.S. Innovation Efforts

The semiconductor industry provides a success story for expanding foreign market access in Japan. Whether improvements are due primarily to overall market trends, expanded efforts of U.S. companies, the U.S.-Japan Semiconductor Trade Agreement, or other factors, expanded market presence in recent years has increased learning from Japanese customers on the part of U.S. device makers, has increased the flow of revenue for next-generation products and processes, and has facilitated the formation of several U.S.-Japan alliances that are investing

large amounts in sophisticated manufacturing facilities and creating high-technology manufacturing employment in the United States.

Although nearly all of Japan's formal trade and investment barriers have been lifted, nontariff barriers related to Japanese policies and private business practices continue to impede access to the Japanese market in a number of key industries. The nature and impact of these policies and practices vary considerably by industry. Several specific examples of market participation barriers are described in Chapter 5, in areas such as intellectual property protection; regulation; differences in competition policy (including weaker antitrust enforcement in Japan); differences in business systems (including keiretsu and intercorporate links, corporate ownership, and the role mergers and acquisitions); differences in financial structures; and access to informal information networks, including industry and trade associations.

The Importance of an Open Competitive U.S. Market

The task force also believes that the largely open and highly competitive U.S. market constitutes a major source of advantage for U.S.-based companies in a range of industries relative to Japan and most European countries.

In the automobile industry it was Japanese competition and direct investment that forced the Big Three automakers and major suppliers to improve their manufacturing and product development performance. In the most rapidly developing, leading-edge sectors, such as information industries and biotechnology, Japanese and other foreign companies have established an R&D presence in the United States to stay abreast of developments.14 The dynamic U.S. market in information technologies is a major factor in the ability of U.S.-based companies to establish de facto standards, which frequently lead to strong advantages in the marketplace.

U.S. Trade Policy

There are several possible approaches the United States might take to encourage greater openness in the Japanese and other overseas markets.15 The first approach would be an aggressive trade policy featuring more vigorous self initiated Section 301 cases, setting targeted market shares and imposing sanctions when they are not reached. A second alternative would be an assertive trade policy that tries to break down general structural barriers, such as intellectual property protection, and address specific market access issues in Japan, with an expanding focus on Asia (similar to current policies and trends). A third approach would be to reduce emphasis on bilateral trade negotiations and focus on multilateral and regional liberalization.

Task force members hold a range of views on whether past U.S. bilateral trade approaches toward Japan have been effective, and on the relative emphasis that the United States should put on bilateral, regional, and multilateral initiatives in the future. The task force does agree that effective implementation of the Uruguay Round, including the stronger dispute settlement powers of the World Trade Organization (WTO), would significantly advance U.S. interests. There are different views on the progress made thus far and on future prospects. Several

members are encouraged by the WTO's ruling against Japan in the shochu case, where a significantly lower tax rate on a native Japanese liquor relative to internationally traded varieties was judged to be trade distorting.16 They would put primary emphasis on strengthening the WTO and would deemphasize bilateral trade approaches.

Other task force members believe that it is too early to tell whether WTO will become effective enough to protect U.S. interests within a reasonable amount of time. They would prefer that the United States maintain a focus on bilateral trade issues and a willingness to use unilateral trade sanctions against trade practices that violate U.S. laws. According to this formulation, the ability of the United States to utilize bilateral and unilateral approaches has contributed to progress on the multilateral agenda, both regionally (in the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation forum) and more broadly. If the United States were to give up these bargaining chips, some countries might have less incentive to make full efforts toward adherence to WTO and future multilateral liberalization.

In addition to agreeing that a strong effective WTO is in U.S. interests, task force members agree that future priority in multilateral negotiations should be on areas where particular market access barriers in Japan have arisen: competition policy and direct investment. Several specific examples are discussed in Chapter 5. For example, stronger multilateral rules on competition policy could help address Japanese private sector practices such as tight links between distributors and manufacturers that have hindered the ability of new entrants to access Japanese distribution systems. Private-sector conditions and practices are also largely responsible for the continued difficulties that foreign and other new entrants have in accessing the Japanese market through direct investment.17 In a multilateral context, progress in these areas will help ensure better returns to U.S. innovators from today's emerging markets than what was possible during Japan's high-speed growth period.

The task force also believes that Japan and the United States will share common interests on an increasing number of global trade issues. In promoting adherence to multilateral rules by developing countries and working to develop common approaches to emerging issues such as trade and the environment, the United States and Japan can contribute to further positive development of the world trading system. This is of major importance to both countries.

Intellectual Property

Intellectual property protection and its relationship with market participation deserves special focus and attention. Improving intellectual property protection for U.S. inventions will be a key determinant of whether the United States gains adequate returns on its investments in innovation. International intellectual property policies are formed through several fora. Harmonization of national intellectual property laws is pursued through the World Intellectual Property Organization. Trade-related intellectual property provisions were included in the Uruguay Round, where developing countries agreed to implement intellectual property protection on a predetermined timetable. Regional trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement and the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation forum have established or are discussing intellectual property provisions. Agreements also have been concluded with individual countries, including Japan.

Pursuing U.S. interests in this area will be complex and difficult but nonetheless very important.18 U.S. innovators experience greater difficulty in gaining intellectual property protection in Japan than in the United States and Europe.19 Particularly for small high-technology companies, market entry can be difficult or impossible without enforceable intellectual property protection.

A few lessons from the Japan experience are clear. To begin with, the situation has improved over recent years, for several reasons. Perhaps most importantly, efforts to strengthen U.S. intellectual property protection over the past several decades, including unification of appellate jurisdiction under the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, have given U.S. innovators a stronger hand in dealing with Japanese counterparts. Trade provisions that allow for blocking importation of products utilizing components or processes that infringe on a U.S. patent make it more likely that Japanese companies will recognize the rights of U.S. inventors, since most high-technology products are developed for a global market. In 1994 the United States concluded two intellectual property agreements with Japan aimed at ameliorating several of the most difficult problems U.S. inventors face in the Japanese system.20

Another lesson of U.S. firms' experience with Japan regarding intellectual property protection is that implementation and enforcement are at least as important as written policies. This has been the case with China as well, where U.S. intellectual property rights complaints center on China's lax enforcement of its own laws.

U.S. policies to improve global intellectual property protection for U.S. inventions will probably continue to be multifaceted in coming years, taking the form of multilateral, regional, and bilateral agreements and steps to monitor and enforce agreements and patent harmonization. In addition to steps already being taken, the task force has developed an additional initiative. This comes from the observation that gaining intellectual property protection in Japan has been particularly difficult for some fundamental inventions, such as the integrated circuit patent of Texas Instruments. Since these sorts of inventions have a relatively high impact on the U.S. economy, taking steps to ensure global protection for key innovations would be worth exploring. The task force suggests that the U.S. Trade Representative and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office jointly set up a system to monitor patent applications for key innovations in Japan and perhaps other large markets where U.S. innovators have experienced difficulties.21 U.S. inventors could request that the progress of their Japanese applications and post-grant enforcement be monitored. If the invention does not achieve timely and effective protection, government-to-government talks could be initiated, with the possibility of WTO or other action if satisfactory results are not realized.

Lessons and Imperatives for U.S. Companies

The Japan experience provides a number of lessons for U.S. companies seeking to participate in markets and build technological capabilities worldwide, particularly in Asia. Attention to the following elements may help ensure that U.S. companies establish strong positions in Asian markets and manage the risk of creating potential competitors:

-

US. innovators should protect intellectual property carefully, particularly in the United States. Although protecting intellectual property in Japan and other countries has been and is likely to remain difficult, U.S. companies such as Texas Instruments and IBM have found that the effort is well worth it. In addition, because potential competitors are likely to seek access to U.S. markets, effective protection of intellectual property rights in the United States is a critical element in ensuring that products based on infringed technologies do not pose a threat in the U.S. market.

-

Where possible, build market participation "tollgates" into technology transfer deals. Although transfer of know-how may be a requirement for entering some rapidly growing Asian markets, care should be taken to ensure that partnerships build a long-term position in the market. For example, Motorola's deal with Toshiba reportedly made given levels of technology transfer to Toshiba contingent on Motorola reaching specified sales levels in Japan.22

-

Cultivate host country allies. In a historical example, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) played a key role in pressuring the Japanese government and soft drink companies such as Kirin to allow Coca-Cola's entry into Japan in the 1950s because MHI stood to benefit as a licensed manufacturer of Coca-Cola bottling equipment.23

Maintaining U.S. Capabilities in Science, Technology, and Innovation

Another key priority for the United States will be to maintain capabilities in science, technology and, innovation, including manufacturing. A favorable environment for innovation has a number of elements, including a dynamic market (as discussed above), supportive policies in areas such as capital formation and regulation, as well as public-and private-sector investments in science and technology.24

Federal Role in Science and Technology with Commercial Applications

Although the task force recognizes that all the elements of a favorable innovation climate are important, issues related to the federal role in technology research and development with commercial applications were the focus of particular task force deliberation because U.S. policy changes in this area have partly been prompted by the competitiveness challenge that emerged in Japan. Japan is now making significant changes in its own government approach to supporting science and technology. Several lessons can be drawn from this experience.

The United States has undertaken a number of new initiatives and policy changes since the early 1980s to improve industry-university-government collaboration in civilian technologies with the aim of improving the return on U.S. R&D investments. These include the Bayh-Dole

Act (1980), the National Cooperative Research Act (1984), the Engineering Research Centers program of the National Science Foundation (1985), the Federal Technology Transfer Act (1986), SEMATECH (1987), the Advanced Technology Program of the U.S. Department of Commerce (1991), the High Performance Computing and Communications Initiative (1991), and the Partnership for a New Generation of Vehicles (PNGV) (1993). The task force believes that U.S. innovation is stronger as a result of these efforts. The evidence confirms that the federal government should play a strong role in investing in long-term, high-risk research that provides an R&D platform for next generation products, particularly where agency or broader national interests are directly engaged. For example, Ford credited PNGV-derived technologies in its recent announcement of a prototype ultra high mileage, environmentally friendly vehicle.25 In many cases the social returns to such R&D programs, in terms of improved U.S. economic performance and improved ability to address other national imperatives, will justify public investment in R&D that would not clear the hurdle rate for expected returns for a private company.

Although there are differences of perspective on the task force regarding the appropriate size and emphasis of particular programs and activities, the members agree that government, industry, and universities must continue to work together to improve the effectiveness of existing technology partnerships and to develop new approaches. Japan and a number of emerging techno-industrial powers are seeking to improve their capabilities through higher investments in R&D and more effective industry-government-university links. Japan has traditionally focused relatively more public effort than has the United States on science and technology investments explicitly aimed at enhancing the technology levels and capabilities of firms operating in commercial markets. Although more recent Japanese efforts have had mixed results, there are several examples of success, and a number of experts have pointed out that the value of these initiatives goes beyond sales generated directly by the research results of R&D consortia.26

In light of these experiences it would appear that a pragmatic non-ideological approach should be utilized to improve U.S. capabilities in the future. It will be necessary to monitor and evaluate programs and policies with the long-term view of fostering effective innovation.

Foreign Participation

Another issue considered by the task force is foreign participation in government-funded R&D, particularly in programs targeted at commercial or potentially commercial areas. Several recent reports have addressed this issue.27 Currently, the United States and other countries have a variety of policies for regulating foreign access to national technology programs. There are no multilateral disciplines, except for R&D subsidies that are trade distorting above a significant threshold.28 A number of U.S. programs contain nondiscriminatory performance requirements

mandating that resulting products be substantially manufactured in the United States. In addition, several programs include reciprocity provisions that require the home governments of foreign based participants to grant U.S.-based companies access to similar programs.

The task force agrees that in the future tapping the capabilities of foreign-based companies will sometimes be required to meet the national goals pursued through government R&D programs. However, there are differences of perspective over how the issue should be addressed by the United States in the short term.

Several members point out that there is no evidence that reciprocity requirements advance national interests or actually lead to greater reciprocity. Barring access to otherwise qualified foreign-based companies may deprive a project of important capabilities. In addition, reciprocity requirements go against long-standing U.S. commitments to the principle of national treatment. According to this perspective, the United States should drop reciprocity requirements where they exist today and not include them in future programs. Reciprocal access to foreign government programs should be pursued through the formulation of multilateral rules. The underlying ability of U.S.-based firms to participate effectively in foreign R&D programs should also be pursued through multilateral rules covering competition policy and direct investment, as outlined above. Finally, some members would retain nondiscriminatory performance requirements focused on ensuring that corporate participants retain full-spectrum capabilities in the United States, including R&D and manufacturing.

Other task force members believe that in the absence of multilateral rules reciprocity is a perfectly reasonable condition to insist on where publicly-funded research might result in benefits to companies based outside the United States and to foreign citizens. This is particularly true in the case of Japan. Japanese companies and citizens already enjoy broad access to U.S. R&D conducted at universities and national laboratories. Survey and anecdotal reports indicate that Japanese companies make strategic and targeted use of this access.29 Because of the relatively greater difficulty experienced by U.S. industry in participating in the Japanese market, as described above, U.S.-based companies generally have less ability to participate in Japanese publicly funded R&D. In addition, Japanese and U.S. approaches to formulating commercially oriented technology programs are quite different. While the United States tends to rely on transparent competitive procedures for developing programs, Japan often develops initiatives through informal consultations some time before projects are funded.30 In recent years, foreign companies have sometimes been invited to participate in Japanese programs based on their capabilities. Some task force members believe that at least in Japan's case reciprocity requirements may be warranted for some programs until opportunities to access Japanese programs can be ensured.