2

Funding Graduate Medical Education in the Year of Health Care Reform: A Case Study of a Health Issue on Capitol Hill

Oliver Fein

In the beginning, there was the Clinton Health Security Act (Clinton HSA). Toward the end, there was the Mitchell bill. Then there was nothing. The year was 1994. Graduate medical education (GME) funding was merely a sideshow in the unfolding drama of health care reform. But it was the crucible in which academic medicine forged its relationship to President Clinton's plan for health care reform. This paper traces the evolution of this health policy issue in the U.S. Senate (see Figure 2.1 on how a bill becomes law) as witnessed by one participant-observer. As the paper follows the peregrinations of GME reform through the Senate, it will focus on the sources of information that shaped the final bill and its outcome.

THE CLINTON HEALTH SECURITY ACT

On January 3, 1994, when I started my Robert Wood Johnson Health Policy fellowship in the Office of Senator George Mitchell, Democratic Senate Majority Leader from Maine, I was handed a 1,362-page document labeled S.1775 (the Clinton HSA). The Clinton HSA had been dropped (legislative lingo for introducing a bill) in the Senate on November 22, 1993. I was told that the Clinton

legislative drafters had written the bill so that the Senate parliamentarian would assign it to the Labor and Human Resources Committee, headed by Democratic Senator Edward Kennedy from Massachusetts, who was felt to be sympathetic to its content. Democratic Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan from New York objected, however, declaring that his committee, the Senate Finance Committee, had jurisdiction because there were Medicare amendments. The Majority Leader, Senator Mitchell, settled the controversy by assigning the bill to both committees, promising to reconcile whatever differences might result from dual assignment by authoring a Mitchell Bill that would be the final product introduced on the Senate floor. One of my first tasks was to review Title III on Public Health Initiatives, which contained the GME sections of the bill. The Clinton HSA did the following:

-

Created an all-payer fund for GME and academic health centers (AHCs) of $40 billion over 5 years by pooling GME funds from the Medicare trust fund with a new 1.5 percent assessment on private health insurance premiums (Tables 2.1 and 2.2).

-

Established physician workforce policies (Table 2.3),

-

including a statutory mandate that 55 percent of all residents must complete their training in primary care specialties (family medicine, general internal medicine, general pediatrics and obstetrics-gynecology) and;

-

including a National GME Council to reduce the total number of residency training positions so that the total number ''bears a relationship to the number of individuals who graduated from medical schools in the United States."

-

-

Distributed the "direct" GME* dollars on the basis of a "na-

TABLE 2.1 Proposed Sources of GME/AHC All-Payer Funds, 1996-2000 (in billions of dollars)

|

Proposed Source |

Medicare, No Change a |

Clinton HSAb |

Senate Laborc |

Senate Financed |

Mitchell Bille |

|

Medicare IME |

$29 |

$10 |

$15 |

$25 |

$26 |

|

Medicare DME |

$8 |

$8 |

$9 |

$9 |

$12 |

|

1.5% of private premiums |

$22 |

$35 |

$32 |

$29 |

|

|

Total |

$37 |

$40 f |

$59 f |

$66 f |

$67 f |

|

Medicare savings |

|

$19 |

$13.9 |

$3.3 |

$2.5 |

|

a HCFA projections for the period 1996-2000, based on Medicare/IME payments at the 7.7 percent level. b Congressional budget office (CBO) projections for the period 1996-2000, based on Medicare/IME payments at the 3.0 percent level. c Congressional budget office (CBO) projections for the period 1996-2000, based on Medicare/IME payments at the 5.2 percent level. d Congressional budget office (CBO) projections for the period 1996-2000, based on Medicare/IME payments at the 7.7 percent level. e Congressional budget office (CBO) projections for the period 1996-2001, based on Medicare/IME payments at the 7.7 percent level. f These totals may differ from those in Table 2.2 since they are based on CBO projections rather than specified in legislation. |

|||||

-

tional average per resident (trainee) amount," subsequently estimated to be $55,000 per trainee.

-

Made GME payments directly to "the approved physician training program."

All four of these proposals were a major departure from existing policies:

-

GME had only been supported by Medicare, not private insurance.

TABLE 2.2 Proposed Uses of GME/AHC, All-Payer Funds, 1996-2000 (in billions of dollars)

|

Proposed Use |

Clinton HSA |

Senate Labor |

Senate Finance |

Mitchell Billa |

|

Academic health centers |

$17 |

$42 |

$42 |

$42 |

|

Graduate medical education |

$23 |

$23 |

$25 |

$25 |

|

Graduate nurse education |

$1 |

$1 |

$1 |

$1 |

|

Medical schools |

$0 |

$2 |

$2 |

$2 |

|

Dental schools |

|

|

$0.25 |

$0.25 |

|

Public health schools |

|

|

|

$0.15 |

|

Total |

$41 |

$68 |

$70.25 |

$70.4 |

|

aFor the period 1997-2001. SOURCE: Amounts specified in reported bills. Amounts are rounded. |

||||

-

In 1992, only 33 percent of residents were expected to complete their training in the primary care specialties, and the total number of residency positions was 43 percent higher than the number of U.S. medical school graduates; that is, they were filled by international medical graduates. In addition, there was no national GME council to allocate resident positions (Kindig and Libby, 1994).

-

Direct GME payments varied from $32,358 to $183,369 per trainee. (Association of American Medical Colleges, 1993).

-

GME funds were distributed only to teaching hospitals, not to residency training programs.

The Impact of Expert Panels

Where did President Clinton come up with these new ap-

TABLE 2.3 Workforce Proposals in 1993-1995 National Health Care Reform Bills

|

Policy |

Clinton HSA |

Labor Committee |

Finance Committee |

Mitchell Bill |

|

Mandate percentage of generalists |

55% |

55% |

No |

55% |

|

No. of residencies in relation to no. of U.S. medical schoolgraduates |

Bear a relationship |

Bear a relationship |

No |

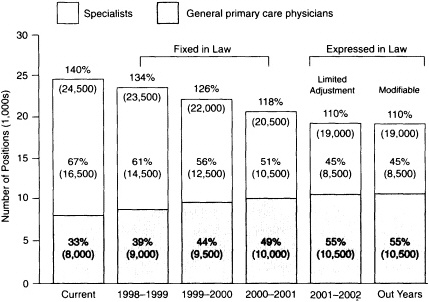

See Figure 2.2 |

|

National council establishes allocation system |

Yes |

Yes |

No National |

Yes |

|

Payment method |

National average per resident amount |

Phase-in "national average" to level of 50% |

Medicare historical payment method |

Phase-in "national average" to level of 50% |

proaches? Table 2.4 lists the expert panels from government, foundations and professional associations that first proposed these changes. Over the years, an impressive base of information and recommendations had been assembled. For example, the Council on Graduate Medical Education (COGME) was created by the U.S. Congress in 1986 and consisted of 17 members drawn from the private sector and government. With the exception of the provision that payments be made directly to residency programs, its Third Report (Council on Graduate Medical Education, 1992) has all the essential elements of the Clinton legislation. COGME states, "All payers should contribute to GME, including Medicare, Medicaid, private insurers, self-insured employee plans, and HMOs [health maintenance organizations] and other managed/coordinated care systems." By including obstetrics-gynecology (OB-GYN) as a primary care specialty (as advocated by Hillary Rodham Clinton), the Clinton HSA proposed 55 percent primary care output, compared to COGME's 50 percent. Rather than adopting COGME's recommen-

TABLE 2.4 Recommended Approaches to Workforce Reform

|

Expert Panels |

Support for 50% Primary Care |

Support for Reduction in Total No. of Residents |

Support for All-Payer Pool |

|

Council on Graduate Medical Education |

X |

X |

X |

|

Physician Payment Review Commission |

|

X |

X |

|

Prospective Payment Assessment Commission |

X |

|

X |

|

Pew Health Professions Commission |

X |

X |

X |

|

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation |

X |

|

|

|

Macy Foundation |

X |

X |

X |

|

American Medical Association |

|

|

X |

|

Association of American Medical Colleges |

X |

|

X |

|

American Academy of Family Physicians |

X |

X |

X |

|

American Board of Internal Medicine |

X |

X |

X |

|

American Osteopathic Association |

X |

X |

|

dation to limit the total number of entry residency positions "to the number of U.S. allopathic and osteopathic medical school graduates plus 10 percent," the Clinton HSA did not use a fixed percentage.

What was the source of the provisions about direct GME payments, in particular, the proposal to make payments to "the approved physician training program"? Again, a congressionally established commission had suggested the language. The Prospective Payment Assessment Commission (ProPAC), which was established to monitor the Medicare program, had recommended a uniform national average per resident (trainee) payment, adjusted for differences in regional wages. ProPAC had also recommended that direct GME payments be made to the residency training program rather than the teaching hospital to encourage more out-of-hospital ambulatory care training. When I arrived in Senator Mitchell's office, the phrase—payment to "the approved physician training program"—was causing substantial agitation among teaching hospitals. It meant that Medicare direct GME payments would be made to training programs, which could then negotiate with teaching hospitals, community health centers, and other sites as training locations. It put the money in the hands of the program directors rather than the chief executive officers of teaching hospitals.

Several outside observers told me that Senator Mitchell's office had played a role in keeping payment to the teaching program language in the Clinton HSA and in excluding a provision that GME funding go through medical school-based consortia. Since the state of Maine has only one small osteopathic medical school, if medical school-based consortia became the only source of GME funding, then medical schools outside of Maine might control GME funding for teaching hospitals in the state. Even though GME consortia were not included in the Clinton HSA, maintaining the provision for direct payment to programs was good insurance against this kind of proposal.

Therefore, I was not surprised to find Dick Knapp from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the Council of Teaching Hospitals (COTH) in my office in January with alternative language to the payment to the teaching program approach: GME payments should be made to "the entity that incurs

the cost," which sounded a lot like the status quo—that is, teaching hospitals. Over the spring of 1994, compromise language was crafted in which GME funding went to "the qualified applicant" rather than a specified training program, teaching hospital, or consortium. This appeared to resolve the problem.

It is a testimonial to the significance of private and quasi-governmental expert panels that so many of their recommendations are incorporated into legislative first drafts. The real test of their power, however, is to measure how many of their recommendations survive into enacted legislation. With the failure of the 1994 health reform effort, this ultimate measure of legislative influence cannot be applied.

The Administration as an Information Source

Information from the Clinton Administration was also critical in shaping the issue within Congress. On January 12, 1994, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH) released a briefing memo entitled Academic Health Center and Workforce Policies. It laid down the rationale for all-payer GME financing in terms that sound quite familiar today: "Private insurers now pay major teaching hospitals 25% to 30% more than community hospitals. In a more competitive environment, health plans will not pay additional amounts the way traditional indemnity insurers do today. In a reformed payment system, we need to provide funds to preserve physician training and quality of care at academic health centers" (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1994). This became the justification for the enormous subsidy for AHCs provided through GME in health reform legislation.

In addition, the Clinton Administration couched its argument for GME reform in a scheme to reduce Medicare spending on GME. The Administration estimated that without the HSA, Medicare would spend a total of $37 billion on GME and AHCs over 5 years. With HSA, this total amount would rise to $40 billion over 5 years, but the Medicare share would drop to $18 billion, resulting in $19 billion of savings for the Medicare program over 5 years (see Table 2.1).

The difference would be made up by assessments on the privately insured—a win-win situation for academic medicine and government alike.

Committee Hearings

This was the lay of the "GME-land" when the Senate Finance Committee worked out its schedule of hearings. In fact, congressional hearings rarely change anyone's mind, least of all the senators themselves. They do, however, create a forum for constituency expression and serve to legitimize the ultimate legislative product, whether or not it embraces the testimony. The Finance Committee held 22 hearings on health care over 5 months, a veritable course in health policy. Looking back, however, the marked up bill was not significantly influenced by the hearings.

Finance Committee staff played the dominant role in determining who to invite to present testimony. Senators on the committee could suggest witnesses, but the ultimate choice was made by Chairman Moynihan and his staff. Selections appeared to be based on at least two criteria: the constituency represented by the witness and the witness's home state. The first Senate Finance Committee hearing on GME was held on March 8, 1994. Each of the four witnesses had been carefully selected. Peter Budetti, a pediatrician and lawyer, was director of the Center for Health Policy Research, which is based in Washington, D.C. He did not come from a committee member's state. He was clearly the staff's witness. Jack Colwill, professor and chair of family medicine at the University of Missouri, appeared on behalf of COGME. Debra Folkerts, a family nurse practitioner, represented the American Nurses Association, the American Association of Nursing Colleges, and the National Nurse Practitioner Coalition. It was no coincidence that she came from Kansas, home of the Senate Minority Leader, Robert Dole. Finally, Clayton Jensen, dean of the University of North Dakota School of Medicine, represented community-based medical schools, which produce graduates, more than 50 percent of whom choose primary care. This witness was a bow in the direction of Democratic

Senator Kent Conrad, the committee member from North Dakota. In sum, this hearing was designed to make the case for workforce reform and primary care.

It is a testimony to the effectiveness of Peter Budetti's presentation (as well as his reputation and experience) that, even though he was an advocate for primary care, he was subsequently hired by the Senate Finance Committee to help with the legislative review of issues relating to GME, malpractice, antitrust, and other physician-associated topics.

About 1 month later, on April 14, the committee scheduled the hearing to make the case against workforce reform and primary care, entitled Academic Health Centers under Health Care Reform. Again, the witnesses reflected a variety of constituencies, with a disproportionate number of witnesses from Chairman Moynihan's state of New York. Spencer Foreman, from New York's Montefiore Hospital and Medical Center and past president of the AAMC represented the AAMC. Paul Marks, a personal friend of Chairman Moynihan and president of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, represented subspecialty and scientific medicine. Raymond Schultz, director of the Medical Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, represented teaching hospitals. Stuart Altman, a Brandeis University economist and chair of ProPAC, was the staff's witness.

There was one anomalous witness at the second hearing. Daniel Onion, director of the Maine-Dartmouth Family Practice Residency Program. Although he had an academic affiliation with Dartmouth, Dr. Onion seemed out of place. As he said, "I feel like an onion in the petunia patch," since he was a family physician among high-powered leaders of academic medical centers. The primary reason that Dr. Onion appeared was that he came from Maine, the state of Majority Leader Mitchell. He went on to steal the show with the hearing room audience, if not with the senators, describing how he and a nurse provided cardiopulmonary resuscitation to a ski accident victim while a urologist and orthopedist stood around unable to turn their specialist skills to the general emergency need of the moment. Dr. Onion spoke for establishing a target of 50 percent primary care, in the context of reducing the number of residency

positions to 110 percent of the number of U.S. medical school graduates. He also advocated direct payment of GME monies to residency programs.

It was only after the hearing concluded that it was realized how deeply held Chairman Moynihan's views on workforce reform were. When Dr. Onion was reviewing the transcript of his testimony he came across a Moynihan remark that none of us had heard on the day of the hearing: "I do note that under the guise of simplicity he [Dr. Onion] argues that his plain, simple half herbal teachings cost half again as much as [training] at Sloan-Kettering." We all knew that Chairman Moynihan had to defend his New York constituency, which trained 15 percent of the nation's residents, even though it has only 7 percent of the nation's population. This bias in attitude toward primary care was widely shared by those closely allied with the nation's top academic medical centers.

THE MARK-UP

The Finance Committee markup of HSA took place in the last week of June 1994 and extended into the Saturday of the July 4th weekend. The markup was conducted in the context of the Labor and Human Resources Committee's release of its final bill on June 9, 1994. Senator Kennedy was viewed as a friend of academic medicine and had reported out a bill that was extremely favorable to academic health centers and that specifically created a new funding pool for medical schools.

The Labor and Human Resources Committee bill provided more funds for GME and AHCs than Clinton's HSA—a total of $68 billion over 5 years, compared with Clinton's $41 billion (see Table 2.2). This included Kennedy's creation of a medical school funding pool that was worth $2 billion over 5 years. The origin of this medical school fund dates back to an October 1993 Saturday morning meeting at the White House of 13 deans from the most prestigious, research-intensive medical schools in the United States. This group, which dubbed itself "the Saturday Morning Working Group," was organized by Michael Johns, dean at Johns Hopkins School of

Medicine, and Herbert Pardes, dean at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons. They had formed the group because they felt excluded from the Health Reform Task Force and underrepresented by their traditional lobbyist, the AAMC, and so they hired their own lobbyist (Capitol Associates, Inc.). It was clear that the proposal for a $2 billion medical school fund was a product of their efforts.

Senator Kennedy seemed to recognize that if these huge sums of money were to go into physician training then they needed to be accompanied by a workforce policy that emphasized primary care. So the Kennedy bill included the 55 percent goal for primary care and a national council to reduce the number of residency training slots without a specified target. The result of markup in Senator Moynihan's Finance Committee was essentially identical to that in Senator Kennedy's Labor and Human Resources Committee with respect to GME funding levels, but there were no workforce goals for primary care or for reducing the number of residents.

The vote on GME financing in the Finance Committee was tense. Republican Senator Malcolm Wallop from Wyoming, on the basis of the popular Republican platform of opposition to any new taxes, introduced an amendment to eliminate the premium surcharge that was the source for all new funding for GME, AHCs and medical schools. The committee had 20 members—11 Democrats and 9 Republicans. If the Republicans stuck together, it would take only two Democrats to swing the vote in favor of the amendment, and all new funding for GME and AHCs would be dead. The voting always started with the Democratic majority and the ranking member, Democratic Senator Max Baucus from Montana. Like Senator Wallop, he had no medical school in his state, and with no workforce provisions in the bill, Senator Baucus voted in favor of the amendment. Democratic Senator Jay Rockefeller from West Virginia was the wild card. He had always said, ''No money for GME/AHCs without workforce reform." However, he voted against the Wallop amendment. Ultimately, only one Democrat voted for the Wallop amendment and three Republicans opposed it. Financing for GME and AHCs was saved, but without workforce provisions.

THE MITCHELL BILL

On Saturday, July 2nd, hours after the Finance Committee had completed its markup, Senator Mitchell gathered his health care-related staff: John Hilley, chief of staff; Bobbie Rosen, his tax man; Lisa Nolan, his budget specialist; Christine Williams, his health care-related legislative assistant; Parashar Patel, a detailee from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; and myself. Mitchell said, "When I referred this bill to two committees, I promised my colleagues I would put together my own bill. You have three weeks" (G. Mitchell, pers. com., July 1994). He instructed us to work with staff from both committees and outlined the broad principles he thought we ought to follow.

As we learned later, there was one problem with these orders. The chief of staff of the Finance Committee forbade his staff from meeting with us when members of the Labor and Human Resources Committee staff were present. This contributed to some of the tensions that subsequently developed around GME.

In many respects, the Labor and Human Resources and the Finance Committees had reported out similar GME financing bills. As can be seen on Table 2.1, the dollar amounts for AHCs and GME were the same in both bills. However, the amount of savings for Medicare was substantially larger in the Labor and Human Resources Committee bill compared with that in the Finance Committee bill, since the Labor and Human Resources Committee reduced the Medicare indirect GME adjustment factor from 7.7 to 5.2 percent, whereas the Finance Committee maintained it at the 7.7 percent level that existed then. ProPAC had advocated reducing the indirect GME adjustment factor to 5.2 percent and the Clinton HSA had reduced it to 3.0 percent. Those preparing the Mitchell bill decided not to buck Moynihan on GME financing and accepted the Finance Committee's funding levels.

However, the big difference between the bills was in workforce provisions. The Senate Finance Committee had no workforce provisions, whereas the Labor and Human Resources Committee bill followed the Clinton HSA in recommending 55 percent of residents in primary care and a national commission to establish a system of

allocating residency positions (see Table 2.3). The Labor and Human Resources Committee bill also copied the Clinton HSA with a provision that the number of first-year residencies "bear a relationship to the number of U.S. medical school graduates," but did not specify a percentage, like COGME's 110 percent. The Labor and Human Resources Committee departed from the Clinton HSA, which suggested that direct GME be allocated on a "national average per residency (trainee) amount," by recommending a phase-in of the national average to 50 percent of the historical rate and 50 percent of the national average over 4 years. This was a concession to states like New York that historically had direct GME rates that were much higher than the national average.

Moynihan's opposition to workforce provisions was based at a minimum on his need to be responsive to the teaching hospitals and academic medical centers in New York. Every other committee that had reported out a health care reform bill had workforce provisions. How could such a large government subsidy of GME and teaching hospitals be legislated without accountability for the outcome, particularly since many analysts ascribed a substantial part of medical inflation to the overproduction of doctors?

The staff preparing the Mitchell bill, tried to craft a bill that still had workforce integrity, but that would phase in workforce goals more gradually and loosen the legislative constraints on any national commission in the fourth and fifth years, so that there could be flexibility to respond to the unintended consequences that might result from adherence to rigid percentages (see Figure 2.2). Mitchell's staff worked closely with Labor Committee staff and received substantial help from Senator Rockefeller's staff. Mitchell's staff tried to work out compromises with the Finance Committee staff, but it was difficult without being able to get everyone in the same room. Frankly, Mitchell's staff felt that the GME and AHC funding components of the legislation were in jeopardy without the workforce provisions and thought that Senator Moynihan would ultimately see it that way also.

The Clinton Administration's control of data was also significant. As Mitchell's staff rewrote the GME financing sections of the

FIGURE 2.2 A flexible proposal to reduce first-year residency training positions. SOURCE: The Mitchell bill.

Mitchell bill, they were interested in the impact of workforce reform provisions, particularly on rural states and New York State. With this information Mitchell's staff might have been better able to speak to Senator Moynihan's fears of an adverse impact on New York. It turned out, however, that these data were viewed as political dynamite by the Clinton Administration, because they showed the wide disparity under existing Medicare formulas in the distribution of GME funds between states (e.g., for every GME dollar spent in North Dakota, $217 was spent in New York). What was worse from the Administration's perspective was that the Mitchell bill increased this disparity (e.g., for every GME dollar spent in North Dakota, $368 would be spent in New York). Thus, the Administration held back on releasing the data until mid-August, when it was too late to influence most senators' positions.

The Senate Floor

The Mitchell bill was introduced in the Senate on August 8th. Senators Moynihan and Kennedy were assigned as floor managers for the bill. When Senator Moynihan vigorously protested the GME and AHC sections of the bill, Senator Mitchell decided to drop the provision on reducing the number of trainees to a percentage of U.S. graduates from the second version of the Mitchell bill.

This did not mollify Senator Moynihan, however, who rose on the Senate floor on Saturday, August 13th, and railed against the remaining workforce provisions, saying: "This invites the wrath of the gods ... this is a sin against the Holy Ghost." He also added, "There is a staff member somewhere who wants this. And no matter what we do, we keep getting it" (U.S. Congress, 1994). I was floored. Yes, there were many staff members who favored regulation of the physician workforce. There was also the weight of 20 years worth of information molders: private and government expert panels, the record of the other committees in the U.S. House of Representatives that had reported out health reform legislation, and the opinions of multiple senators and representatives, all of whom favored workforce provisions, not to mention the political calculation that if academic medicine wanted $70 billion worth of support (almost twice what it presently received from Medicare) then it would have to accept some accountability for the workforce product.

Senator Moynihan was unyielding. He drew up an amendment that stripped the Mitchell bill of all workforce provisions. As the debate proceeded on the Senate floor, amendments to the Mitchell bill began to be entertained. Amendments alternated between Republican proposals and Democratic proposals. At first, each side offered amendments in which the outcome was clear. This avoided votes that were meaningful in terms of estimating the ultimate support for the bill. Everyone recognized that the Moynihan amendment was different. It was not clear whether the Democrats would stick together in opposing the Moynihan amendment and how many Republicans would support it. If workforce provisions were stripped from the Mitchell bill, would there be majority support for GME

and AHC funding? For the Democrats, the Moynihan amendment was a meaningful, defining amendment. Within the Democratic leadership there was substantial debate about when to introduce it. Just at the point that it appeared that a decision had been made to put forward the Moynihan amendment as the next Democratic amendment, the House voted and passed the Crime Bill. Senator Mitchell decided to suspend debate on health care and move the Crime Bill to the Senate floor. Although there was considerable negotiation with the Mainstream Coalition* over the ensuing weeks, the Mitchell bill never made it back to the Senate floor. On September 27, 1994, Senator Mitchell announced to the press that health reform was dead.

CONCLUSION

Senator Mitchell often pointed out to his staff that if health reform did not pass in 1994, one consequence would be that everyone would know how to make cuts in Medicare and Medicaid in the future. He predicted that the next Congress would just cut Medicare and Medicaid without expanding coverage for the uninsured. So it was not surprising that Medicare GME funding was on the congressional cutting table all through the 104th Congress. No doubt it will be one of the first items on the agenda for cutbacks in the 105th Congress.

Can anything be learned from the saga of health care reform in 1994? Certainly, the information provided by expert panels and commissions is a significant force in shaping health care legislation. In addition, the role of the Administration's control of the flow of information is important. However, these forces may frame the issue, but they pale in significance compared to the role of interest

groups. It is striking how much interest groups shape the final product. The deans' Saturday Morning Working Group was able to take the opportunity of national health care reform and insert entirely new support for medical schools. The New York academic health centers were able to exert enormous influence to maintain the status quo, even if it jeopardized enhanced funding for the total enterprise. When these forces combine with the ideological preferences of a powerful member of Congress, then politics overwhelms policy.

In a recently published book, Theda Skocpol (1996), professor of government and sociology at Harvard University, dismisses most conventional explanations for the Clinton failure in health care reform. She feels that President Clinton should have gone for a less regulated system requiring higher taxes. "I conclude," she writes "that President Clinton should have been less worried about pleasing the deficit and budget hawks. He should have done what his conservative critics falsely charged him with doing—acted more like a Democrat in the New Deal tradition, by combining new Federal regulations with generous subsidies to those affected" (Skocpol, 1996, p. 182). Ironically, when it comes to GME funding, the Mitchell bill would have done precisely that. It increased taxes (through an assessment on private health insurance premiums), provided generous subsidies to academic medicine, and established flexible new federal regulations in workforce policy. Academic medicine will not fare as well for the foreseeable future.

POSTSCRIPT

Was any of the "information" generated for the 1994 health reform effort carried over into the 104th Congress? With the Republicans in control, the 104th Congress was looking for ways to slash the domestic budget. The Clinton health reform effort had shown where $19 billion of Medicare savings could be found over 5 years—in GME. GME seemed like a perfect target. Congress could cut GME without perceptibly reducing benefits to individual Medicare enrollees.

The long shadow of Senator Moynihan still hung over the Senate Finance Committee, and the addition of Republican Senator

Alfonse D'Amato from New York only enhanced its effect. The Senate Finance Committee ultimately passed only minor changes. GME funding cuts were limited to $9.9 billion over 7 years and were taken only from indirect GME payments (by reducing the indirect medical education adjustment factor from 7.7 to 4.5 percent), not from direct GME payments, which remained untouched. These cutbacks were ameliorated by a carve-out of GME payments to managed care companies who enrolled Medicare patients into health maintenance organizations, but refused to contribute to the expense of training residents. Workforce policy encouraging primary care or discouraging international medical graduates was not included.

In the House, the Ways and Means Committee was much more radical than the Senate. It cut Medicare's GME support substantially, replacing some of it with funding from general revenues. This maneuver was accomplished by borrowing another Clinton health reform concept, the creation of a GME and an AHC Trust Fund. The GME and AHC Trust Fund received contributions from Medicare and from federal government general revenues instead of Clinton's 1.5 percent assessment on private health insurance. By eliminating payments for trainees beyond first board eligibility, the Ways and Means Committee implicitly adopted a workforce policy that discouraged subspecialty training. By phasing out all funding for non-U.S. citizens, they were essentially limiting federal GME funding to American medical graduates, a much more radical policy than Clinton's.

Of course, all of these proposals were stopped by President Clinton's veto of the Balanced Budget Act of 1995. It is likely, however, that the 105th Congress will revisit these issues earlier rather than later in 1997. Therefore, it is instructive to summarize what the joint Senate and House conference committee adopted and what it rejected. The GME provisions adopted included

-

AHC and GME Trust Fund—not an all-payer trust fund, but one that reduces Medicare's contribution by partially replacing it with general revenue funding;

-

cap on the number of residents at the August 1, 1995, level;

and

-

reduction of GME payments to 25 percent for trainees after first board eligibility. This primarily effects subspecialty fellowships.

The conference committee rejected

-

limit on non-U.S. citizen international medical graduates;

-

carve-out of GME funds from Medicare payments to Medicare health maintenance organizations; and

-

formation of an Advisory Panel on Reform in Financing of Teaching Hospitals and GME.

Anticipating 1997's congressional debate, the AAMC testified before the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Health on June 11, 1996. AAMC supported creation of a GME Trust Fund and called for a "shared responsibility approach," another way of saying all-payer financing; limitation of Medicare GME to U.S. medical graduates; and expansion beyond hospitals of the entities that may receive GME payments, such as medical schools, multispeciality group practices, GME consortia, or other entities that incur the costs of training (but not training programs directly), to remove the barriers to training physicians in non-hospital-based ambulatory settings. These will be the GME issues that face the 105th Congress. They all surfaced in the 1994 health care reform effort, and Congress is all the more sophisticated because of it.

REFERENCES

Association of American Medical Colleges. 1993. GME Census. SAIMS Database. Washington, D.C.: Association of American Medical Colleges.

Council on Graduate Medical Education. 1992. Improving Access to Health Care through Physician Workforce Reform: Directions for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration.

Kindig, D.A., and D. Libby. 1994. How will graduate medical education reform affect specialities and geographic areas? Journal of the American Medical Association 272:37-42.

Skocpol, T. 1996. Boomerang: Clinton's Health Security Effort and the Turn Against Government in U.S. Politics. New York: W.W. Norton.

U.S. Congress. 1994. Congressional Record 140(113):S11667. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1994. Academic Health Centers and Workforce Policies. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Washington, D.C. January 12. Memorandum.