2

Presentations and Discussions

ORIENTATION TO WORKSHOP GOALS

Welcome

Welcome Dave Clark, Polar Research Board

On behalf of the Polar Research Board of the National Research Council, it is my pleasure to welcome you to this workshop1 concerned with NOAA's Arctic research initiative. The principal focus of this workshop is to develop a series of suggestions that the NOAA will find useful in guiding the next phase of the Arctic Research Initiative.

Today, as I have watched people file in this room, I thought that things have changed in the Arctic in the last few years. Thirty years ago all of those in the U.S. who were concerned with the Arctic would have fit in just one comer of this room. Yet this year alone, I have attended five Arctic research meetings, most of which included different people than are here today (and the last meeting had 200 in attendance). People like Garry Brass and others here have probably attended even more Arctic-related meetings with different people.

This is good because it represents a dramatic shift in research emphasis in this country. We recognize new problems in the Arctic, problems that we want to address today. During the past 30 years, we have developed new techniques to solve some of the old problems. Perhaps most important is that the funding available now for research to solve some of these Arctic problems is at a more substantial level than it has ever been. The really good news is that with so much activity in the Arctic now, many of the problems that we worried about for years are being addressed and addressed in a good fashion. And of course, we are learning more about this intriguing and strategic part of the earth than we hoped to learn 30 years ago.

The bad news for those of us who have been involved for a long time is that we no longer have a monopoly on Arctic research. This includes the annoying fact that our manuscripts are criticized more heavily and we don't get as much money for our personal research because there are so many more people working in the area. Nonetheless, the fact that Arctic research is moving forward is a great thing, and the Polar Research Board, among many other groups, is very appreciative of NOAA's initiative.

Today we have a specific objective and only a few hours allotted to accomplish it. We have many speakers scheduled and, more importantly, many issues to discuss. The proceedings of this workshop will be published by the National Academy Press, and we hope that our discussions will be useful in guiding NOAA's Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research in defining and pushing forward their Arctic Research Initiative. Just how good these proceedings are and just how useful they are to NOAA depends, of course, upon the full participation of each of you in attendance. So, we are ready to go. I will ask Walt Oechel, who is serving as the chairman of the workshop, to define our specific plan of action for today's activities.

Workshop Structure and Goals

Walter Oechel, Polar Research Board

I think this is a fantastic opportunity to have some formal input into NOAA's contaminant research program. What we would like to do today is review the key gaps in areas requiring research in Arctic contaminants, review what NOAA has done up to this point, and what it is doing now. After that what we will try to identify the areas where NOAA is best able to make a contribution, and this includes looking at what other agencies are doing and what NOAA's unique capabilities are.

So, we should consider NOAA's capabilities, the possible synergism with other agencies and institutions, and try to identify major gaps in contaminants research. As we use the term here, contaminants research is fairly broadly defined. We want to help NOAA build a coherent program, something that is identifiable and can move the field ahead.

The structure of today's workshop is to briefly review NOAA's Arctic Research Initiative and, also, hear a bit about the U.S. Arctic contaminants research meeting from Fairbanks last August. Jim Baker, NOAA's top administrator, will talk about "the big picture" and how the issue of contaminants and the Arctic Research Initiative should fit into that larger context. We'll then have a series of talks reviewing various NOAA programs and how they contribute to our understanding of contamination in the Arctic. We will also look at perspectives from outside NOAA to make sure that what NOAA is doing fits in the broader context. All this will easily take all morning. Before we break for lunch, we will have a general brainstorming session to look at the large research questions and try to identify additional research points that we may want to discuss in the breakout groups. Then during lunch we will ease into the breakout discussions, and after

lunch have focused discussions on the three major research questions. We'll return here for a plenary discussion and reports from the breakout groups.

Time is very limited and we have a very ambitious agenda for one day. PRB member Gordon Cox has volunteered to be the timekeeper. So, he has a large hook, and will be ruthless in its application.

Your meeting books contain a description of the Arctic Research Initiative, which you'll note focuses on the Bering Sea region and Western Alaska. The main elements within the program have been a study of natural variability and studies of anthropogenic influences, including contaminants transport and fate plus issues like Arctic haze, ozone, and UV changes. NOAA has been very interested in the impacts on ecosystem structure and function. So, those are the major issues that we want to talk about today. We need to ask not just what research is need but where can NOAA make the largest contribution? How can NOAA best work with other agencies' programs and in the end come up with a coherent, well-focused program.

So, with that I would like to ask Joe Friday to give us a general introduction. Joe Friday is the Assistant Administrator for OAR, for anyone who doesn't know.

Welcome

Joe Friday, NOAA's Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research

I have been the Assistant Administrator for NOAA's Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR) for only two weeks now, but I wanted to welcome you because this is an area that I am looking forward to with great enthusiasm and great interest. I am not a newcomer to the Arctic issues. I served as the Department of Defense representative to the Interagency Arctic Research Coordinating Council back when I was Director of Environmental and Life Sciences as a young, dashing Air Force colonel. That is many years ago unfortunately, 1979 through 1981.

At that time, some of you may remember one of the things that we were involved with doing in that time period was trying to evaluate the physical plants and everything else that should be there, and this was the time frame in which the Navy recognized it was probably cheaper to deploy from the lower Forty-Eight than it was to maintain the full capacity up at NARL (Naval Arctic Research Laboratory). As a result, it phased down some of the activities up at Barrow.

During the 16 years that I spent in the National Weather Service, I visited every one of our Alaskan sites in January or February because I didn't want the folks to think that I just went up there to do salmon fishing. I have never been salmon fishing in Alaska, as a matter of fact, but I have visited every one of the sites there. I participated in a joint review of the high Arctic sites in the Canadian Environmental Service, Alert, Eureka, Resolute, Mould Bay. When we landed at Mould Bay our plane contained 14 people, and we tripled the population of the entire island.

I am looking forward to understanding the current state of the science in the Arctic. I don't want to run afoul of the timekeeper or take time from Alan Thomas because he will be giving you the directions and expectations from OAR's perspective, but I would say one thing. I like the point of view that this is a short meeting. Short meetings are better than long meetings, I think, but we have to remember what we are trying to accomplish. I am in the process of preparing our quarterly management reviews, and as I went through the various things that were listed as accomplishments in the last quarter there were several meetings listed.

I, personally, do not view a meeting as an accomplishment. Descartes' definition of management may be ''I meet, therefore, I am,'' but I think that is wrong. What we have to do with meetings is really try to focus and accomplish something, as both Dave and Wait pointed out earlier. I think Alan is going to be carrying the same message. We really want to come away from here with a direction to go.

I probably won't be able to contribute much to the breakout sessions because my database is too stale, but I am looking forward to understanding what the issues are and the status of things. And again, I welcome everyone here.

I'm not one to be accused of micro management, except occasionally, and I don't intend to micro manage the laboratories and the activities in OAR either. I do want to understand what is going on, and I do want to be able to focus on what the real issues are and make sure that we are contributing in real ways. Again, I am glad that you are all here, and I hope you have a productive meeting.

PRESENTATIONS

NOAA and Arctic Contaminants Research

Alan Thomas with Eddie Bernard, Dave Hofmann

I will be sharing my time with Eddie Bernard and Dave Hofmann, but let me just start by talking a little bit about the context; context is important because you always have to know the agency's mission. One of the points I keep making is that there are lots of things we can do, but somehow we have to relate it back to what it says on that sign on our door.

In general, NOAA has a lot of interests in the Arctic. Probably the primary two are forecasting and warning of the weather in the Arctic and fisheries management. We have other programs like the role of the Arctic in climate, but one of the things we have found very hard is to find an integrating way of handling activities in the Arctic. One of the things that is clear to me is that when we look at some of these research issues, we have a kind of an integrator. One of the things that I am particularly interested in is how do Arctic activities relate together, and one of the reasons it is a problem is that our missions tend to be global or very large scale, and the Arctic is one component of a much

larger mission area, whether it is forecasting the weather globally or climate or fisheries management.

This frustration on how you coordinate within an agency was one of the rationales behind us setting up the Cooperative Institute for Arctic Research (CIFAR) a number of years ago. One of the things we found in our interactions is that many times universities, where they have certain loci themselves, allow a lot of people to come together in a way that it is hard here in Washington. At universities, you start with the substance, and then you worry about the policy.

So, that the context of what we are doing. The Arctic Research Initiative has been driven by a lot of activities. Garry Brass and the Arctic Research Commission have been very interested in NOAA and our opportunities. Also, the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program (AMAP) is one of the main driving forces, and I want to just recognize Ed Myers from NOAA who has worked hard on a very skimpy amount of resources to try to coordinate AMAP activities throughout the federal agencies and at least do something from the U.S. side. So, for a lot of reasons we have arrived at having the opportunity to implement a small, but hopefully useful new program, the Arctic Research Initiative (ARI).

We took this opportunity driven by a number of forces, and it came to focus fairly quickly last year. To implement the ARI, NOAA initially reached out to the universities and hopefully down the road to the international community. The ARI received $1 million its first year. That's not a lot, but there are many significant things you can do for a million dollars. We started with having this cooperative institute. We asked Gunter Weller, Patricia Anderson, Ted DeLaca and others to help pull together the first makings of this program. I talked to the Polar Board about a year ago that we were going to do something. Hopefully, today we can report on what we have done in year one.

In setting up the first year of the Arctic Research Initiative we invited input from key NOAA players. Fisheries Service was represented by a couple of people from their Seattle-Alaskan Fishery Center and NOS and NWS and I talked to Walt Planet about NESDIS input.

Because of the short time frame available to plan the first year we dealt largely with University of Alaska scientists. We had a good turnout; there were a number of others from the state and, through Garry Brass, we had input from the Commission. We advertised the availability of support through NSF.

ARI funds did not go only to the University of Alaska; although because of the process we used a lot of the support there. The kind of criteria that we put on is that we wanted to build partnerships between NOAA scientists and university scientists, and that would be a good way of trying to get both very high-quality science and mission-relevant activities.

We also paid attention to ongoing activities so that we could add value to some of the activities that are ongoing. We obviously stayed within our mission but we tried to address some of the Arctic policy issues and concerns that were coming out of AMAP.

I think we now have a better idea what AMAP is proposing, and so one of the things that we wanted advice on today is how can we put that into our plan, and, also, how we focus on achievable results. We actually have a process going. We have some research ongoing, and that is moving forward.

Now, in terms of the focus, both this past year and a general sense in the future, NOAA is very interested in natural variability. That is one of the things that we have done for a long while, and that is very important. We think it is important that when we look at contaminants we still look at the natural variability in the environment, particularly because the polar regions have enormous natural variability. Also, and Walt referred to this, contaminants is a very broad area.

Last year, for example, if you look at points four and five on the list of research themes, No. 5 is really marine contaminants, and there is a lot of effort on that within NOAA, and that certainly is one of the areas in which there is a lot of attention. But we also are going to look at Arctic haze and UV, and I think in the broader sense carbon flux is really going to be something that is important from a climate perspective. So, I wanted to emphasize that we view this in a very broad context of what needs to be done, and so, we hope that you look at it in that sense.

Then just very quickly, the two really major areas were one, the Bering Sea green belt and processes in ecosystem production. That has been a focus of some interest to our Fisheries Service, interest to our research program and other parts of NOAA, and we were able to add, I think, value to some of the activities that are going on, as a part of our study of the variability in the Bering Sea and Western Arctic. The other major activity was anthropogenic influences on the Western Arctic and Bering Sea. So, those are the two larger topics that will be addressed later.

Before I turn this over to Eddie Bernard and Dave Hofmann to talk in more detail about what was supported, let me add that what we did last year was to run a process that actually ended up getting implemented in FY 1997. That was one of our goals: to show that we could manage a successful program, one that included an open process for input from other universities and agencies.

We intend to run a process that has an international dimension and tries to leverage the resources that we have here since we want to be able to do our part in terms of upholding the U.S. role in things like the Arctic AMAP program and the International Arctic Research Center program as well as some of the other international activities.

As I said before, monitoring and data collection in terms of contaminants in the traditional sense is certainly one of the things that we are interested in because of the fisheries and the native populations and the interests around Alaska. But the broader issue of UV and related stratospheric ozone depletion is also important and in fact there was a major program up there this year, the Polaris program that had NASA, the universities, NSF and NOAA participation. And then there is climate change, which we did not fund this year but I think is of ever-increasing importance.

In terms of our expectations, we are looking for how can we improve the ARI; what is the best way of going about broadening the program, recognizing that we probably can expect somewhere in between 1 and 2 million dollars this year.

You have to think about what you can do for that kind of money, and in NOAA we want results because we are a mission agency. We want the science to be as relevant as we can to the issues addressed by our Fisheries Service, National Ocean Service, the Weather Service, or our climate program. In that context I think I would be remiss to say that I believe that we have not focused on the Arctic from a climate perspective as much as we need to. We have spent a lot of time in the tropical oceans and topical areas over the last 10 years. So, we ought to try to see what we can do within the Arctic with the resources we have. Any questions?

Questions/Discussion

PARTICIPANT: Alan, you mentioned a one-to-two million-dollar level of effort. Do you envision this to be a long-term NOAA program that would eventually be part of the NOAA base effort?

DR. THOMAS: That is always our hope. We don't give up easily.

DR. OECHEL: Alan, what was the process by which you got to the Bering Sea area and Western Alaskan Arctic as a geographic focal point?

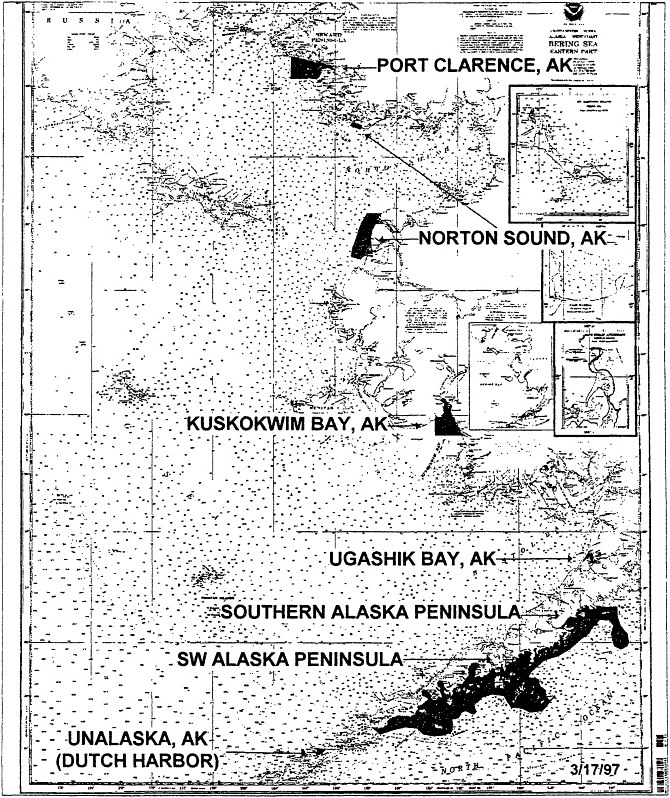

DR. THOMAS: Internal to NOAA we have a number of activities. The Bering Sea is very important for the Fisheries Service. We have done work on fisheries oceanography in that area, the donut hole problem on the international side.

Also, there is some evidence that was presented at our workshop that there are some climate signals like the North Pacific Oscillation and others that we need to pay attention to, some very large changes in that area, and you know, Alaska is an enormously productive area. So, we are driven by our mission to work there. Also, that is not to say that we wouldn't work in the Arctic Ocean because in fact, we have a monitoring station at Barrow. That is a very important area for us, and if you look at the haze and the UV, there is an interest, but for us Alaska is the Arctic. It is the first order, that we do work in Fram Straits and various other parts. We do, and we would like to, but if you look at it from a practical sense, our support comes from working on fisheries management, weather forecasting, climate and things like that.

DR. OECHEL: But to understand contaminant impacts, even in the Bering Sea, it seems like large-scale transport processes are extremely important, and yet I don't necessarily see those reflected in the program right now.

DR. THOMAS: Probably not at the million-dollar level. Ultimately we would like to model that, because certainly large-scale processes are relevant. But our program, for now, is rather small for that. As time goes on, I think we will work with the Weather Service and the university in looking at atmospheric transport, and this is an outgrowth of things like looking at volcanic and other activities. For now, though, the question is what can you do usefully for $1 million?

DR. OECHEL: I guess my question was about the process, but it sounds like it is almost more obvious within NOAA that that was the area to go rather than opening it up and then coming down to that area.

DR. HILD: My name is Carl Hild. I am with the Rural Alaska Community Action Program. The question I have, the Department of Commerce does have an American Indian Alaskan Native policy. How was that applied last year for the expenditure of $1 million, and how do you anticipate it is going to be applied for this coming year?

DR. THOMAS: We are going to try to get input. We will have workshops as we did in Fairbanks. We sought input probably not as broadly this year as we should but we are going to try to find out who and try to invite interested parties to the workshop. I think we supported some work ultimately in areas of interest to the native population of Alaska as I believe through one of the proposals. So, we have gotten a little bit, and I am just saying that that is one of the issues in front of us; how do you broaden this participation.

DR. HILD: Would it be possible to put something in the announcement of opportunity that you anticipate people should reflect this policy because it is a Department of Commerce policy?

DR. THOMAS: Right. One of the other issues that I think we talked a little bit to Garry Brass on the sustainable development, Arctic sustainable development activity, and certainly that is a part of what NOAA is interested in.

I would like now for Eddie Bernard to come up to talk about the first area of natural variability and then Dave Hofmann will talk a little about the contaminant area.

Eddie Bernard

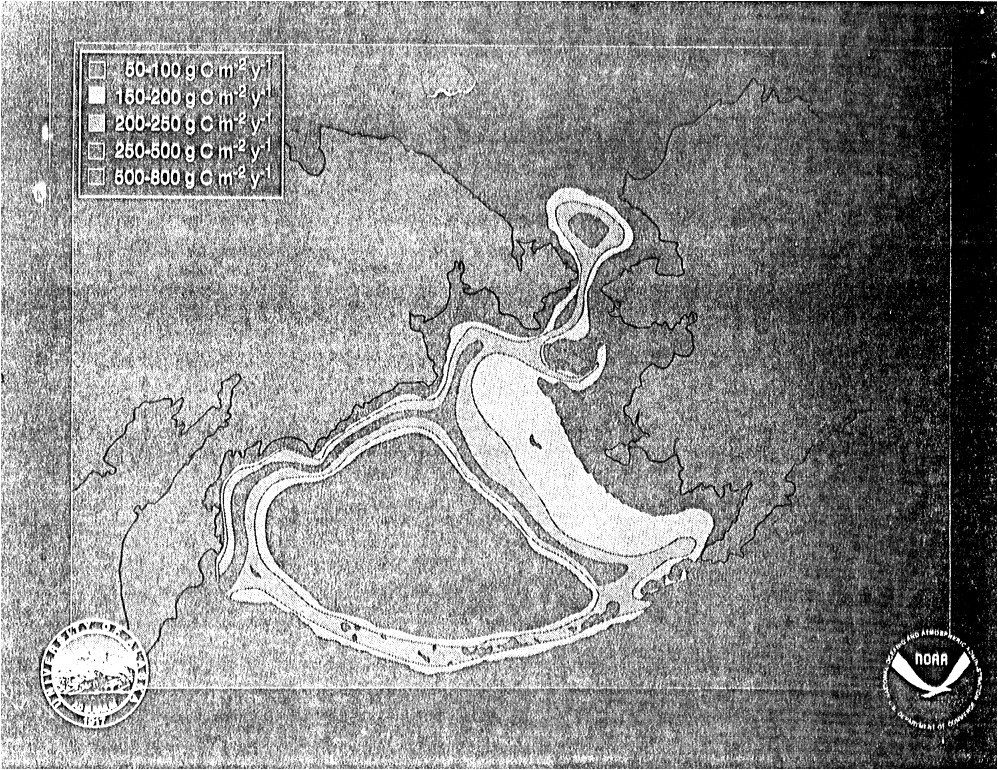

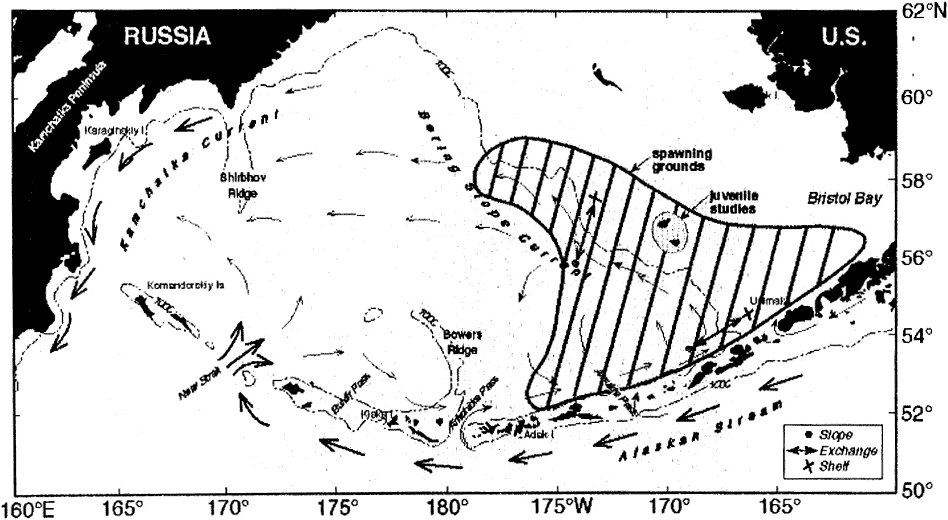

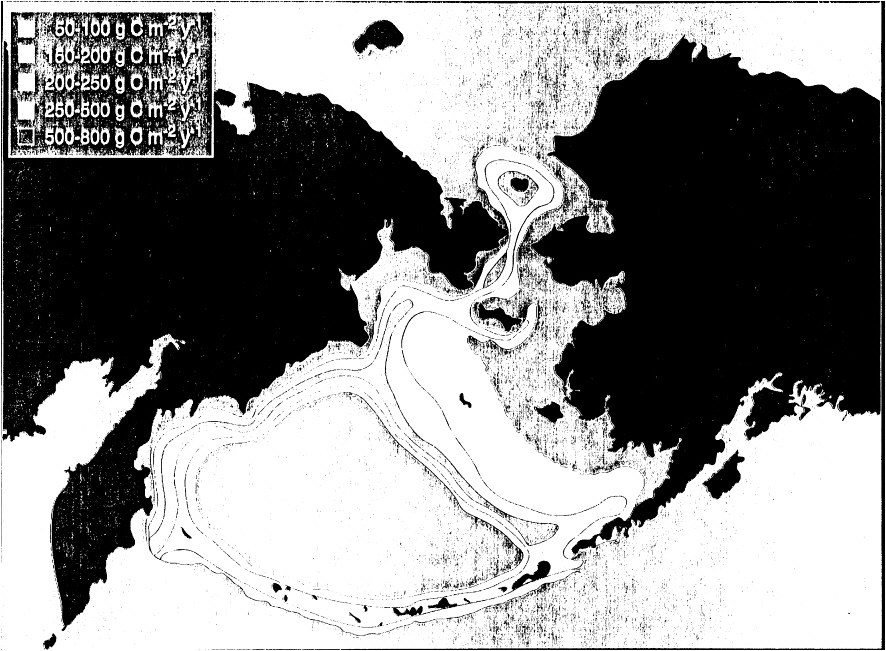

As Alan indicated, nine of the 15 proposals were associated with natural variability. The motivation for this is to understand the existing productivity of the Bering Sea. This is a composite of numerous years of investigation, and it identifies a high zone of productivity along this shelf.

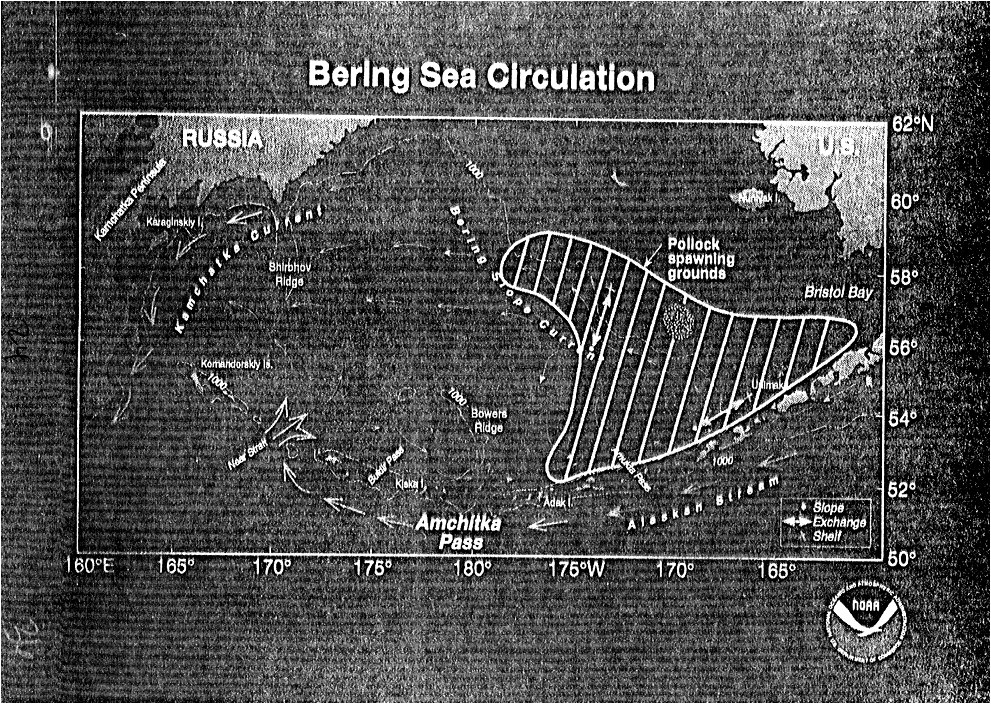

This is the topography of the Bering Sea. This is a deep basin by this wide shelf here, and so, as a result of this high productivity the United States derives about 40 percent of its tonnage of fisheries from this body of water, and actually about 10 percent of the entire biomass of the planet is actually produced in this area. One of the questions is why such high productivity, and over years of investigation we have come up with a schematic concept of the way the circulation works in this area. There are lots of detailed mechanics involved in this that we need to talk about in order to understand some of the variability.

NOAA's interest, as Alan said, is in fisheries and because the fisherman are out there, of course, the Weather Service wants to provide good forecasts so that when vessels ice up and when they hit big storms we don't lose lives unnecessarily.

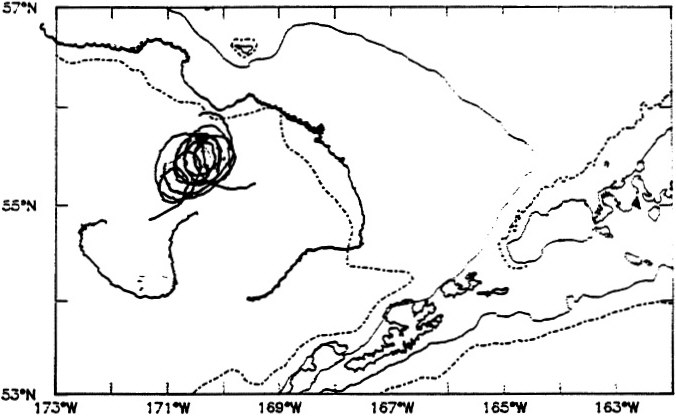

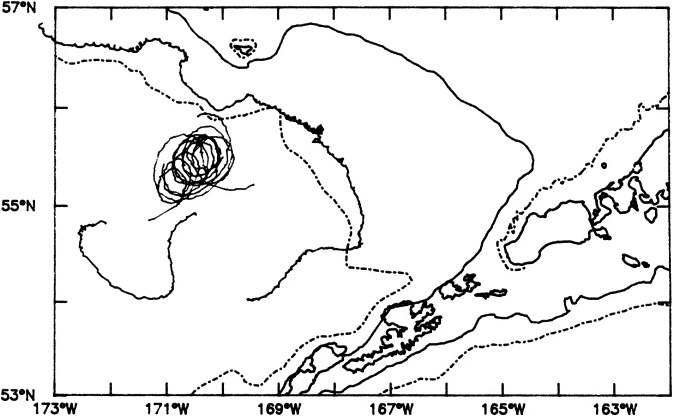

So, this is the general circulation pattern. There is a big gyre that goes in the basin and then as this gyre follows the contours of the bathymetry that gives rise to a lot of interaction. That is the key right there, this confluence of high productivity with these physical mechanisms seems to be one of the products that we want to focus on. And just to give you an idea in terms of natural variability, there were two studies in the Bering Sea ecosystem that focused on bioindicators. One is the analysis of seal hunting up in the Chukchi Sea area to look at hunting for 50 years from 1920 to 1970. Since 1970, there has been pretty good population dynamics but to use the indigenous people of Siberia to sort of understand how their hunting went up and down. A second bioindicator is a spotted seal study that is done by the Alaska Fish and Game Department in which they tagged 21 seals from 1991 to 1993, and these data are being analyzed to see what the correlation is between ice pack and fluctuations in the marine mammal populations.

Okay, so, those are sort of gross bioindicators of what is going on. The other projects that are funded are process studies, and the hypothesis driving this is that there is a lot of interaction fight here and in order to take advantage of some NOAA activities, the Coastal Ocean Program is sponsoring a program called the Southeast Bering Sea Carrying Capacity. They had several cruises lined up for this spring to collect data in this green belt.

Now, although the green belt image I showed you earlier is a composite of many data, no one has actually gone and systematically surveyed this area until the first cruise in May, and so, let me just show you some preliminary results of that cruise. First of all, the first cruise went out and deployed some moorings and some drifters, and this was all money that was supplemental to the Coastal Ocean Program Southeast Bering Sea carrying capacity. Investigators included several people who were looking at both the nutrients and the physical transport.

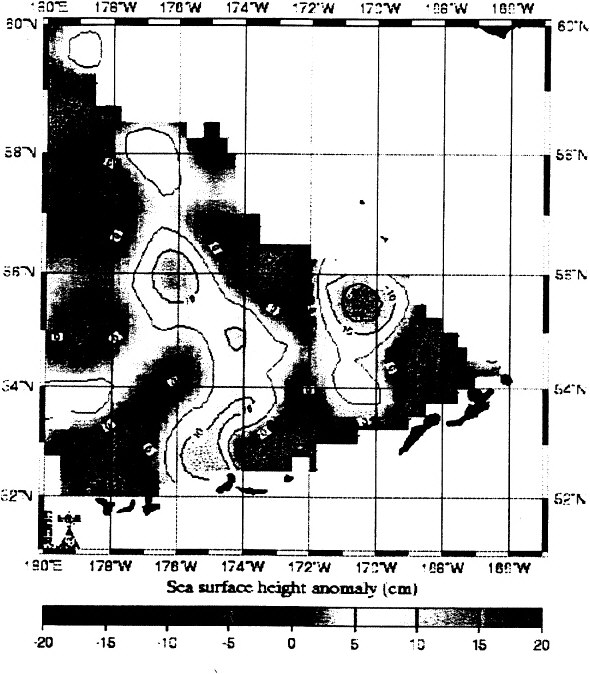

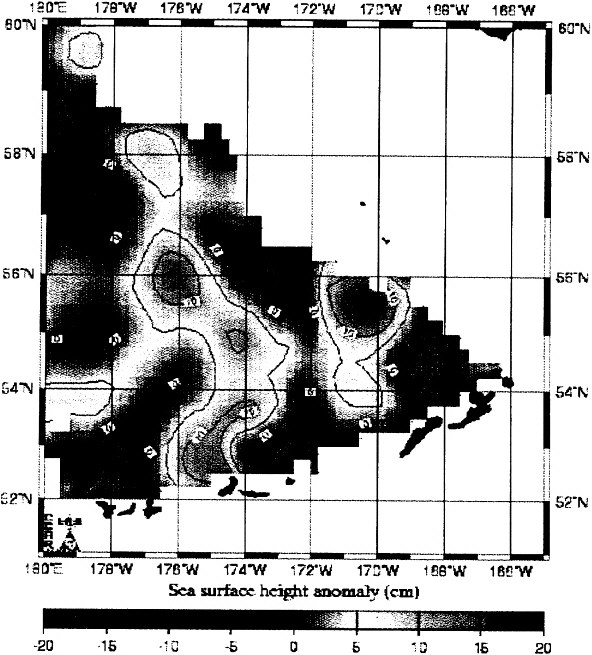

There is a web page in Colorado that puts out near real time altimetric measurements, and this is the Aleutian Archipelago here and this is the Bering Sea covered here. What you are looking at here is a high elevated area here that represents an eddy, and it seems like these features, these eddy features, are a dominant mechanism in which transport takes place from the deep ocean, nutrient-rich waters to the shelf where it supplies food that sustains this high productivity.

This information is brand new. This collaboration didn't exist before the Arctic program was under way, and now, after a few discussions this is available over the web page.

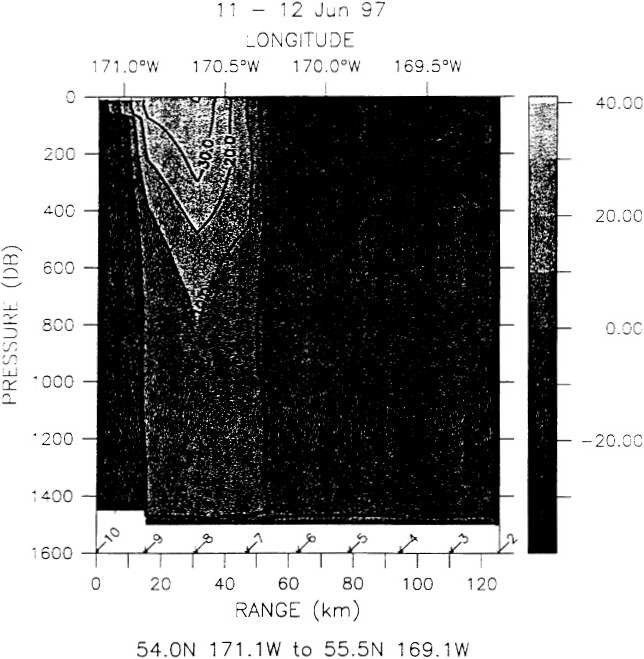

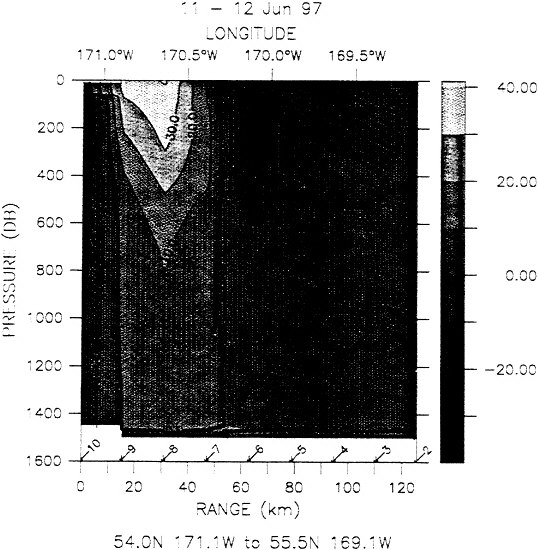

We took our ship fight out to the middle of this because it was under way, made surveys in real time of the current velocities and what you are looking at here is a cross section.

Let me guide you here. You are looking at a cross section through this eddy, fight through the middle, okay? This is a circulation pattern, and there is a clockwise eddy. So, the flow is coming out of the page and into the page, but notice that this eddy is not symmetrical. It is distorted toward the shelf side, and in measuring chlorophyll inside the eddy and outside the eddy we found that it was greatly intensified inside the eddy. So it

looks like this eddy stretching mechanism is actually acting as a vertical flux in bringing nutrients from the deep ocean up to the shelf and supporting the nutrients, and this is the first data we have that actually supports this hypothesis that has been advanced, and we are very excited about it.

In addition to making direct measurements we also seeded this eddy with drifters, and there you see the drifters. It is hard to tell from this, but they are going in a clockwise direction, and these drifters have chlorophyll measuring devices on them. So, you can actually track the chlorophyll inside the eddy. As we would expect, these are high.

This one that got pulled out of the eddy is low. So, what we see here from the preliminary results is that it looks like the eddy structures are very important in transporting nutrients from the deep ocean basin up to the shelf which supports sustained productivity.

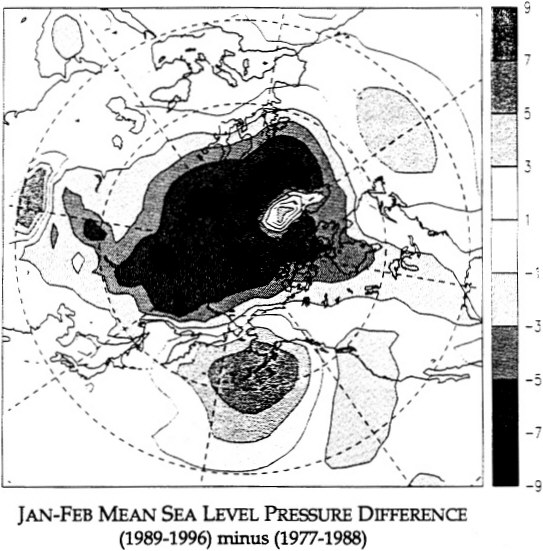

In addition to the oceanographic features that cause these eddies, what supports them is a study of the meteorological programs, and we are studying the natural variability by looking at the changes in the Aleutian low and one pattern that has emerged is that it looks like if you take a look at some long period fluctuations in climate you will see that the Aleutian low actually seems to prefer two modes.

One mode is in the Gulf of Alaska, and the other mode is in the Bering Sea. If you look at the time period between 1989 and 1996, versus the 1977 to 1980 time frame, it looks like over that period there have been some shifts in sea level pressure, and for the non-meteorologists in this area this represents a rising of the sea level pressure which would depress, would suppress the intensity of the Aleutian low, and then this would be lowering in this area the high pressure system. So, in effect, this is lowering gradient and lowering some of the intensification that is taking place in the high Bering Sea. For us simple oceanographers it seems like the obvious thing that is going on here is that when you have an intense low pressure system that sits here it brings up warm air from the south, and it creates lots of mixing, and it is a very energetic system.

When it is in this system, when the Aleutian low sits over here, it is bringing in cold air. It is less intense. There is not as much misting, but them will be more ice because of the cold. So, these are the natural variabilities that we are studying. We are, also, studying the planetary boundary layer at Barrow, Alaska to see what changes have taken place.

So, all of this is loosely woven together. Like Alan said, all of these programs are linked to other programs, and probably about one-third of the funding from the Arctic program is actually being supplied for all the science that is being accomplished.

Dave Hofmann

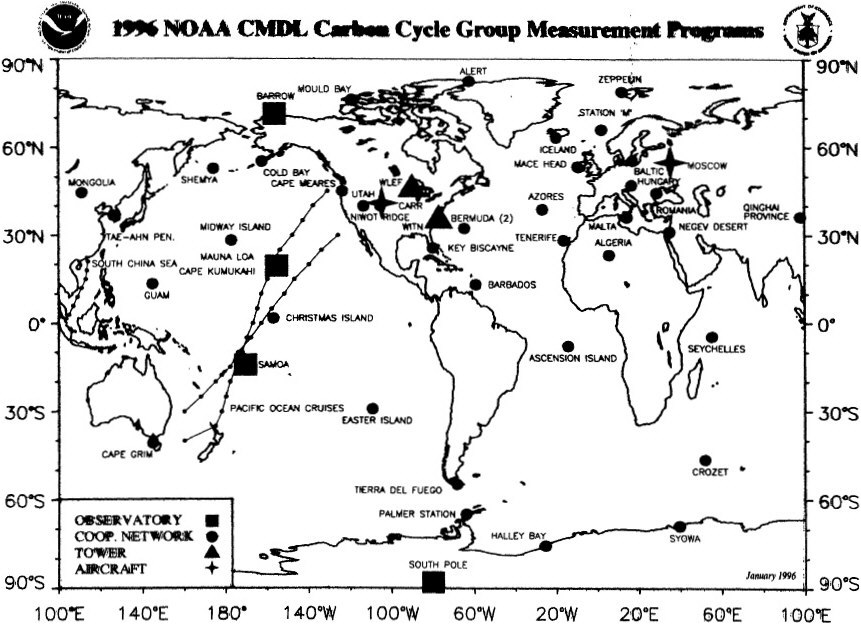

That was an overview of the ocean part of the Arctic Research Initiative. I am going to say just a little about the air part. There are actually four laboratories that are either involved at the present time or are going to be involved in the Arctic research involving atmospheric research. There is the Aeronomy Lab doing stratospheric ozone work with the Polaris mission at the present time, and the Air Resources Lab doing surface energy balance and flux. The Environmental Technology Lab develops instruments which will be applied in the Arctic through various programs, and then I am associated with the Climate Monitoring Diagnostics Lab, which has been in the Arctic for a long time. I am going to say just a little bit about how the research that we have been doing in the past 25 years in Barrow has played a role in the new initiatives.

NOAA has been in the Arctic for a long time through various programs. This is just an example of the carbon cycle group's measurement program here in Alaska, the main observatory in Barrow, and we, also, collect samples at a number of other locations for our climate carbon cycle studies.

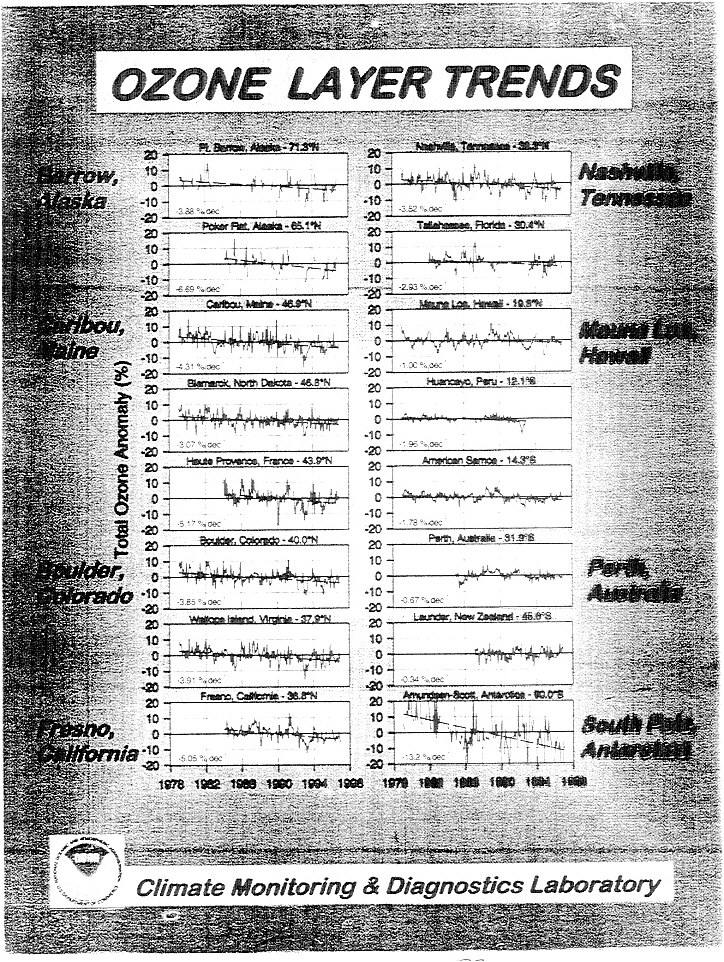

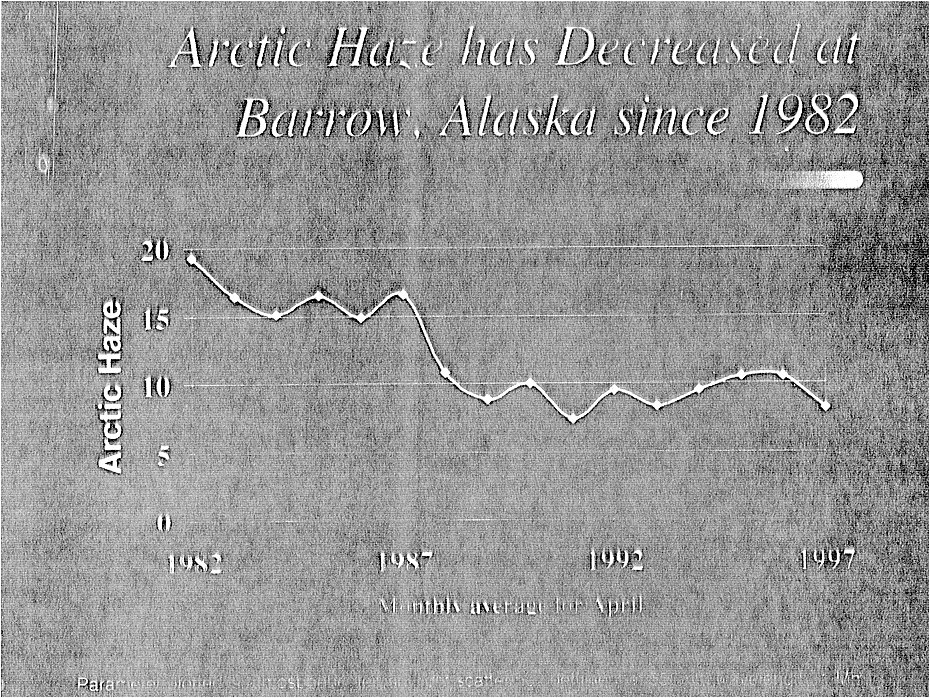

We have been doing research in the Arctic for a long time, and three of the programs that were funded under the Arctic Research Initiative involve long-term trends in arctic haze, measurements of UV radiation in the Arctic, and we do actually have a program aimed at climate change in the Arctic. I am going to focus in on that one because it seems to be related to this issue which is one that is very well known and that is arctic haze.

Back in the eighties it was a big deal. Arctic haze was very obvious. It was considered a product of transport of industrial emissions, some thought from Russia but probably Eurasia. Our monitoring at Barrow suggested that over the years this is the scattering that you would get if you brought this air into a box and shined a light on it. So, it tells you how many particles are in the atmosphere.

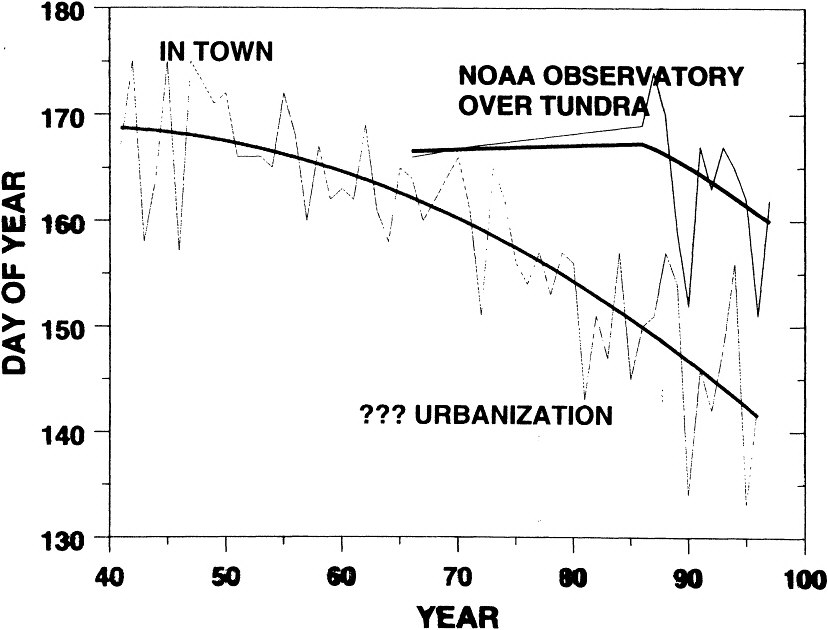

Along about in the late eighties this thing leveled off and is now rather constant and the first idea that was put forward was that it was because of the Soviet Union's economy changing and things like that. But there are other indications that things are changing in the Barrow area. One of these is the history of Barrow snow melt date. This is in town where it is obvious snow is melting earlier in the year by a week or two, which suggests climate change.

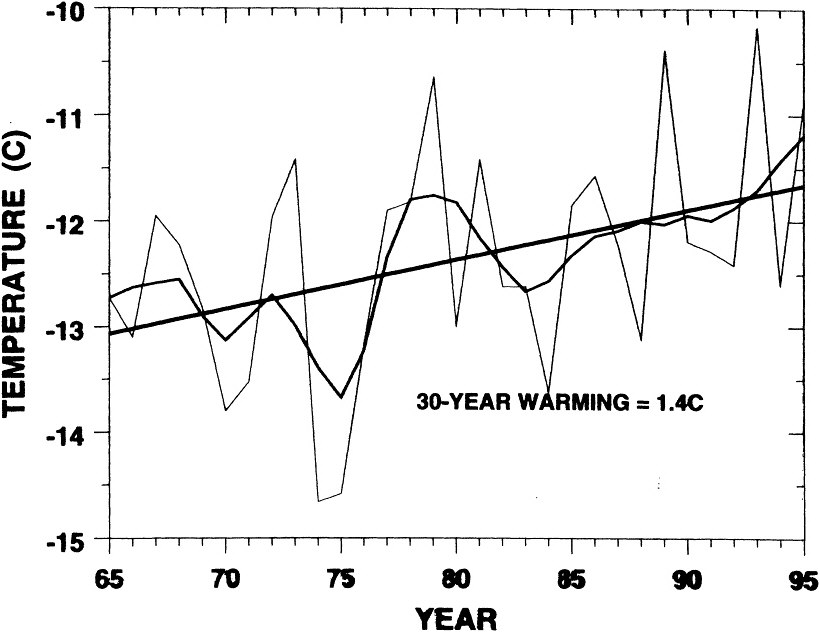

Our observatory is somewhat out of town over the tundra, and while they were in reasonably good agreement back then, they are now quite a bit different. The snow melts in town quite a bit before it does out at the observatory, and while both seem to be getting earlier, this difference seems to be getting greater. So there is a question: is there some effect of urbanization? Perhaps the most interesting thing is the actual climate trend measured at the observatory over the last 30 years: in the last 30 years average temperatures for the year increased by about 1.4 degrees C, which is substantial, and one of the research programs is specifically looking into explaining this, and it seems not to

be related to increases in greenhouse gases. While that may be a component of it, that is not the driving force.

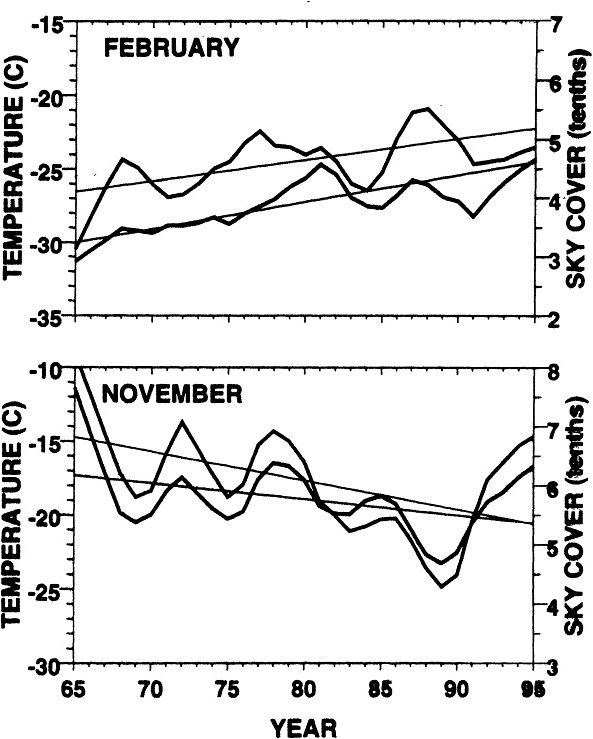

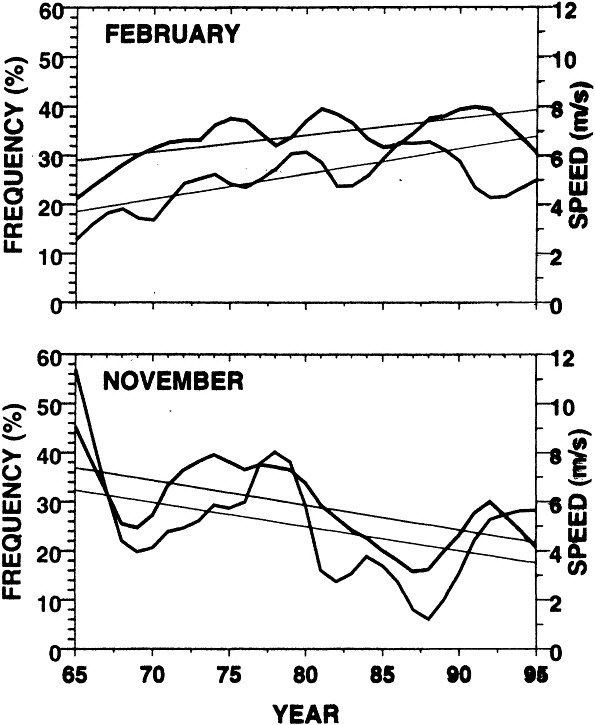

If we look at, for example, by month, in February we definitely see this is getting warmer, and we also notice that it is correlated with cloud cover. So, as it has been getting warmer, it has been getting cloudier over the last 30 years. But if we look at another month, in November, we see a completely different picture. On average it is getting colder, and it is getting less cloudy. So, it is not a simple change in climate as you might expect from greenhouse forcing. It is a much more complicated situation, and we have been looking at, for example, the question of this transport changing, is circulation in the Arctic changing, and if you look at some of the obvious things like the frequency that southwest winds occur, and you see, also, the correlation both in the speed of the winds. In February, when it is getting warmer the frequency of southwest wind is increasing, and the wind speeds are increasing slightly, while in November when it is getting colder the frequency of southwest winds is decreasing.

So, at least initially it clearly looks like it is a transport phenomenon, a change in the general circulation. This could even be related to large-scale changes. So, this one program is going to look at this in more detail and try to pin down why climate is changing.

The NOAA CMDL Carbon Cycle Group maintains 4 measurement programs. In situ measurements are made at the CMDL baseline observatories: Barrow, Alaska; Marina Loa, Hawaii; Tutuila, American Samoa; and South Pole, Antarctica. The cooperative air sampling network includes 45 fixed sites and 3 commercial vessels. Measurements from very tall towers and aircraft began in 1992. Presently, atmospheric carbon dioxide, methane, carbon monoxide, hydrogen, nitrous oxide, sulfur hexafluoride, and the stable isotopes of carbon dioxide are measured. Group Chief: Dr. Pieter Tans, Carbon Cycle Group, Boulder, Colorado, (303) 497-6678. ptans@cmdl.noaa.gov.

Questions/Discussion:

DR. FRIDAY: I wanted to give a glimpse of some kinds of activities I think aren't reflected here—such as a couple of projects at the Fisheries Service and the university. I hope Fisheries will have 5 minutes, and I hope that we can get input on that contaminant program.

DR. COX: I have a general question. There is a document that we were provided called NOAA Backgrounder pertaining to the ARI, and it is interesting that in this backgrounder some key performance measures were identified for the Arctic Research Initiative for year 1, 2 and as the program moved forward. Can you comment on whether or not the year 1 performance measures were met or are in the progress of something being done for them?

MS. ELFRING: This is a document that the Board got as background when we were preparing. So, you might want to tell what that performance measure is because other people don't have that document. (This document is reproduced in Chapter 3.)

DR. THOMAS: Ed Myers is here, and he wrote the backgrounder, I believe. I don't want to put it all on his shoulders. This is a 3-year-old document, I think. Obviously from a practical standpoint, that was something we set out a number of years ago. What I think we started is a much more modest effort. Instead of an MOU we have brought some people together, and we intend to extend that including the state and we have tried to work with other agencies through programs that are up there. The ARM program, for example, a number of the projects build on ARM, and SHEBA and things like that. So, we haven't formally gotten to there, but you are right, that was one of the things.

DR. COX: One other important measure here that none of the awarded studies addresses is the involvement of the Alaskan Native community. There is a measure in the initiative of formal accords and other arrangements for involvement in the initiative of the North Slope and other regional organizations.

DR. THOMAS: We don't have formal arrangements. It is our intention to make it more formal. That was discussed as part of the planning process, and it seems to me there is a proposal that has cooperation in it.

DR. COX: I was very impressed with the amount of work and planning that went into developing the ARI and the call for proposals, but when I looked at what was eventually awarded there seemed to be a bit of a disconnect in terms of meeting some of the key objectives of what was originally developed in the planning process.

DR. THOMAS: All I would say there is it was recognized that we built ongoing and natural variability more this year than ultimately we probably will, partly because the nature of what was available was more developed, that is we, one of the reasons we actually got involved and asked the PRB to come is we need I think more program development, more planning in the area of what should we do in the contaminant part of the program broadly defined, and that is partly why we are here. That was discussed at the time. Given the time line we took the best things, and so, we probably allocated more on the natural variability.

The Big Picture: A CENR Perspective on Contaminants Research and Remarks from the NOAA Administrator

D. James Baker

When Alan and I talked about asking the PRB to organize this workshop, our goal was to get more action in the Arctic in research. I wanted to get the PRB involved because I have a special place in my heart for the Polar Research Board. It was the first Academy committee I was ever on, and it was one of the places where I learned how one operates in an Academy committee. It showed me one of the major purposes of the National Research Council, which is to bring able scientists together and talk about issues and generate ideas; it lets young scientists meet famous old scientists and learn from each other.

Larry Gould was the Chairman of the Board when I served in 1972, and he must have been 80 years old then. He looked like he had just come back from the Antarctic. Back then, most of the members of the Board were Antarctic explorers and scientists who had been on Antarctic expeditions, and in fact, I think that was one of the criteria. There was a strong Antarctic slant to the membership.

The Board, a committee then, was known as the Polar Pals, and I remember Gould, with his gravelly voice, welcoming me to the Committee. I think I was one of the first oceanographers to be on the Committee, and he said, ''Well, what are you going to do on the Committee?'' I was just appointed, and I didn't know what you do on Academy committees, and he said, "Well, you are going to be Chairman of the Subcommittee on Oceanography."

I said, "I am?" And so slowly various members explained to me what I should be doing. It was a great experience, and we wrote a document called "Southern Ocean Dynamics: A Strategy for Scientific Exploration 1973-1983," and out of that we did the International Southern Ocean studies experiment. Our input was critical in making that happen.

These are not just rambling comments, but I am leading up to what I wanted to talk about. Having outside communities involved with federal research planning is something we have been trying to push very hard on the Committee on Environment and Natural Resources (CENR), and I think we are making some progress. Let me just say a little about what we are doing on CENR and why I think this kind of community interaction is so important.

If you watched the federal process over the years, there have been various attempts to coordinate federal research activities. In the Bush Administration there was the FCCSET, Federal Coordinating Counsel for Science, Engineering and Technology, a group of federal agencies coming together to do planning. One of the things that the Clinton Administration asked is how do you build on the FCCSET and try to make it even more comprehensive than before. To do this the Administration formed the National Science and Technology Council. The point of the Council is to cover all science and technology issues, and try to coordinate those across the Federal Government. Under the

Council was established a set of committees that would cover all the different subjects in science and technology.

Under the NSTC, we have nine committees, and one of the committees is the Committee on Environment and Natural Resources. This committee is a follow-on to the previous Committee on Earth and Environmental Sciences, the CEES. I have cochaired that Committee with the person who is the Associate Director for Environment in OSTP. That was Bob Watson and is now Jerry Melillo. We have tried to have that Committee look at what is being done in the Federal Government across all of the areas of the environment and natural resources, not just environment and not just natural resources, but looking at the whole thing. There are about 15 agencies that are involved in these subjects. We then put together seven or eight committees, plus a couple of cross-cutting committees, to focus on some specific initiatives that we could accomplish in the Administration.

As we have gone forward with that process there have been a number of things that we have been able to accomplish. We put together a national environmental technology strategy and a program for national earthquake loss reduction.

We organized a big conference on climate impacts on human health. We launched a North American research strategy for tropospheric ozone, the NARSTO program, and we have continued a very strong emphasis on global change and on natural disasters.

So, through our efforts, we have been able to continue some important initiatives and get some focus in the budget process. We have in this past year picked up five areas that we are trying to focus on as we look forward, and the National Science and Technology Council has actually endorsed those five initiatives for the 1999 budget process.

Endorse means that OMB sends a message out to all the agencies and says that these are things that you should be supporting, and if you do support these areas we will look favorably on that in the budget process. Global change is one that we continue to have as a very high priority, and some of the things that you talk about in the Arctic are related to that. Natural disasters is another issue that we are pushing very hard, and we are looking there for a large new initiative, large in terms of dollars. We also are going to continue the North American research strategy for tropospheric ozone, the NARSTO program.

Finally there are two that I think are of special interest in relation to the Arctic and Arctic contaminants. One is the environmental monitoring initiative and the other is the endocrine disrupters. These are both subjects that the community and the agencies have felt are important areas where we need to do something new.

If you look at the environmental monitoring, one of the things that I think we all felt is that we need to build up our environmental monitoring on the ecological side to be as good as we are doing on the physical climate side. We know that we still have some real problems in terms of ecological monitoring, particularly terrestrial ecological monitoring; how do we handle that? So, this idea of a national environmental monitoring initiative is something that Jerry Melillo and others have pushed very hard. Some of you

have been involved in this. Also, this relates to the Vice President's idea of having some kind of report card on the health of the environment that would be produced roughly in the year 2000 or 2001. So, the idea on the national environmental monitoring initiative is to see if we can put in place a monitoring system which will allow us to monitor both the ecological and biological side of earth as well as we are doing with the physical and climate side. With that, we can start to get some real indicators about how things are changing.

The other initiative relates to endocrine disrupters, those estrogen-like compounds in the environment that causes problems with reproductive cycles. We are seeing more and more evidence of the problems caused by these compounds. Obviously, this is related to the whole contaminant problem.

So, we will be looking at those two areas that will be of particular importance. We have in this past few months, reduced the number of committees that we have in the Committee on Environment and Natural Resources. We now just have five, each one focused on what we see as one of our major initiatives. We have the Global Change Committee headed up by Bob Corell. We have a Natural Disaster Reduction Committee headed up by Bill Hooke from NOAA, Bob Hamilton from USGS, and Bob Volland from FEMA. We have an Air Quality Committee. We have an Ecological Systems Committee and then a Toxic Substance and Risk Committee. Under these five committees, we are looking at ways that we can both identify major new initiatives, ways that we can coordinate with lesser amounts of money, and activities that we think need attention but don't require any new funds. We are trying to put together a kind of pyramid of initiatives. I don't have viewgraphs today, but this is all up on the home page for the Committee on Environment and Natural Resources, and you can get there through www.WhiteHouse.com or OSTP.com. All of that is kept up to date so you can see reports, the initiatives, and where we stand in terms of funding.

Let me say a word about the issues that we see facing these federal committees because this is really the important thing. We are into the balanced budget mode where it is very hard to find money. Roughly half the money in the federal budget is in entitlements and those are things that tend to grow rather than go down. Then the other half is divided into three parts. One is national defense. One is interest on the national debt. And the other is everything else in the federal budget. So, we are down in the 16th percent of everything else, and even as the economy gets better and better, as it has been doing, the government and the public expects us to live within a limited budget. So, we have to find a way to do that, and it means that whatever we want to put forward we have to have a very strong case for it.

The other thing that I am trying to do, and this is a kind of meeting that exemplifies it, is to get outside input to government agency planning. Now, this is not as easy to do as one would think. It seems like a logical thing to do, but some federal agencies don't really welcome it.

The academic community tends to think on longer time scales than the agencies, which tend to think on yearly budget cycles. So, you have different time frames between

the government and academia. You have cultures that are not used to being mixed up. During one of my first meetings with the Committee, I said, " I propose that we have some academic people come in here and sit with us and help with the planning," and I thought everybody was going to say, "Yes, great." But, the reaction was more negative than positive, "Why do we want to do that?" I think we are now at a place where this kind of joint meeting should be more the norm than the exception. I am now trying to work some formal arrangements so that we can have the outside community, the academic community, private industry and environmental groups, come in and be part of the planning process. We have found that the more we engage the stakeholders in the planning process the better job we do of doing planning and of making sure that everybody understands what we are trying to do.

So, stakeholder involvement is very important. Then the final thing is that we are continuing to try to make sure that the President and the Vice President are aware of the issues. If you have seen recent speeches by the President, you will hear him speak about global change, about environmental monitoring, about the importance of the environment in general, and this is because of the process of the National Science and Technology Council, which is headed by the President and has Jack Gibbons as the person directly responsible. This puts us at a higher level in the process, and as we've worked through the first four years, I think we are seeing some progress.

Questions/Discussion:

MR. MYERS: I am Chuck Myers representing the Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee. I was particularly interested in your two priority areas, environmental monitoring and endocrine disrupters. Environmental monitoring has been a topic for the Arctic for the past seven years, and in fact, we have in the several agencies been contributing to the Arctic monitoring and assessment program. They have just published a report, State of the Arctic Environment. So, we are actually four years ahead of the overall federal effort. the second area you mentioned was the endocrine disrupters. This is a major part of the U.S. Arctic research plan. We have a section on the assessment of risks to environment and peoples in the Arctic. The question is, how do we translate this planning, which has been going on for several years, into actual resources through the CENR?

DR. BAKER: This meeting is one example and another is the Arctic Research Initiative in NOAA; both are examples of how to work the process. There have been lots of committees and there are lots of good reports that have been written about what is to be done. What we need to do is to turn those reports into some real new resources. The way we do that is by convincing Congress that this is a good thing to do.

We do have a number of important members of Congress who have a special Arctic interest. Senator Ted Stevens, Chairman of the Appropriations Committee is from Alaska. He has an automatic interest in polar arctic issues, and thus it is important that he and his staff and other people continue to be aware of the things that can be done.

We are trying to make the best possible case for environmental issues as we go forward in the federal budget process. So, in our 1999 budget in NOAA you will see requests for things that are basically built on the initiatives that you and Garry Brass and other people are putting together. Your planning helps us make things happen.

DR. COX: Is there some kind of listing of what the nation's priorities are with respect to science and engineering needs, science and technology needs?

DR. BAKER: Yes, every year the National Science and Technology Council puts out what is viewed as the priorities both for this year and then for the long term. In fact, there is a White House document just out called Science and Technology Priorities for the 21st Century. It has a very nice section on the environment and reflects all of the priorities of the Committee on Environment and Natural Resources. I am sure it is pretty widely distributed.

Once again, you can pick that up on the White House home page, go to the National Science and Technology Council and you will see those priorities there. I would expect that most of you had an opportunity to comment on those, and that is something that we are continuing to try to do is to make sure that we have this kind of joint process as we go forward.

DR. WEATHERHEAD: Betsy Weatherhead, University of Colorado. In talking about your priorities I thought it was very interesting that you had no mention of AMAP, the Arctic Monitoring Assessment Program, which seems to lead straight into the priorities that you were talking about, setting up a report card and doing environmental monitoring in addition or in conjunction with the physical monitoring. The U.S. involvement with AMAP has been so terrifically low I think it is noted in the first AMAP report that data from the U.S. is lacking on a variety of subjects.

Can you comment on what you see as the reason for the lack of U.S. involvement and what might be the future for U.S. involvement in this sort of activity?

DR. BAKER: I was trying hard not to mention any specific program because there are lots of very good arctic programs that have been put forward that are woefully underfunded. I believe the U.S. needs to do a better job in standing up to its responsibilities here. The whole point of looking at arctic contaminants as we have here in this workshop and then trying to broaden out an initiative is something I am very interested in trying to do.

AMAP is a program that was discussed with me when I first came in as NOAA Administrator. Alan Thomas and Ned Ostenso gave me some very good briefings on that, and we have been looking for ways. In fact, I think the conversation that we had was, "This is a good program. We have to figure out how we can get this funded," and we are continuing to try to address the issues that you are mentioned.

This is a first step here as we look at priorities how we can handle funding; if we can continue to make a strong case, hopefully we can do better. There is a dilemma: you have responsibilities and needs and new things that ought to be done, but budgets which are flat at best. How do we make things fit? How can we get enough attention on arctic issues now?

There is new technology. There is sympathy in Congress. There is enough interest that we can make something happen. The problems in the Soviet Union with nuclear waste and the attention this has brought has alerted some people; this may help eventually get resources onto these problems.

It is difficult, but I think AMAP has done a good job in terms of identifying what should be done. Hopefully we can do better in participating.

A View from the National Ocean Service

Jawed Hameedi

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Most of you know that Dr. Nancy Foster is the new Assistant Administrator for National Ocean Service. Coincident with her appointment there are likely to be some significant changes in the structure of the organization and probably will affect the way we do business. I do not know what those changes are going to be. Dr. Foster could not be here in person.

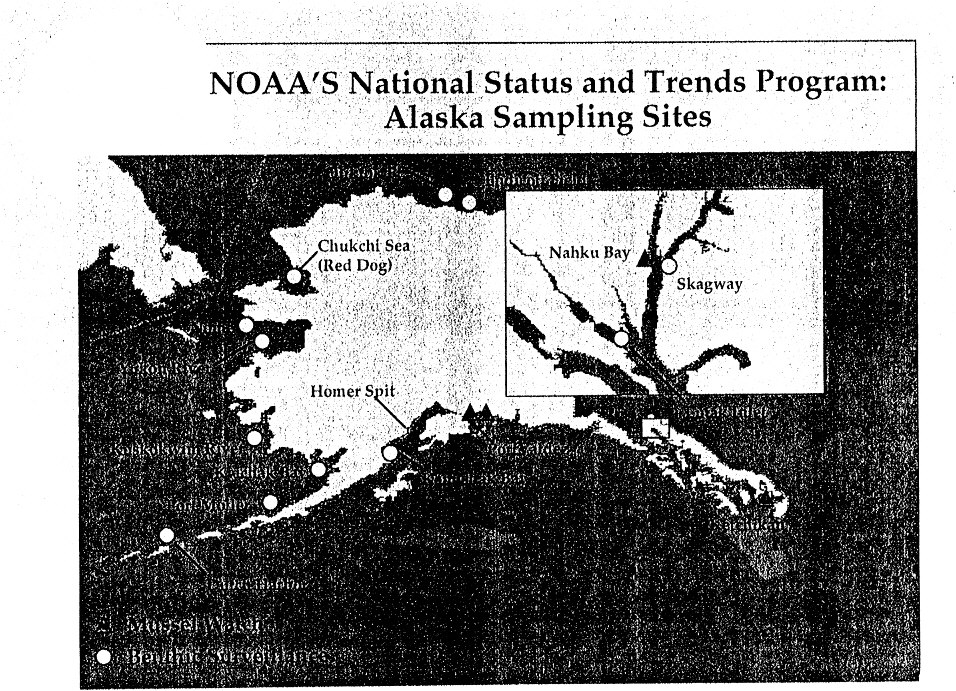

My name is Jawed Hameedi. I have been associated with NOAA's National Status and Trends Program for about 4 years. Before that I was associated with the Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program for about 12 years in Alaska and before that I did some marine acoustics work in the Chukchi Sea and before that I taught oceanography at the University of Washington. If somebody asked me to write the vision and mission statements for the National Ocean Service it would read something like that.

There is a very strong connection between the economic well-being of the country and the quality of the environment, and if you read the mission statement that I have listed here, the concept of environmental quality or conversely that of environmental contamination sort of pervades through all of these items.

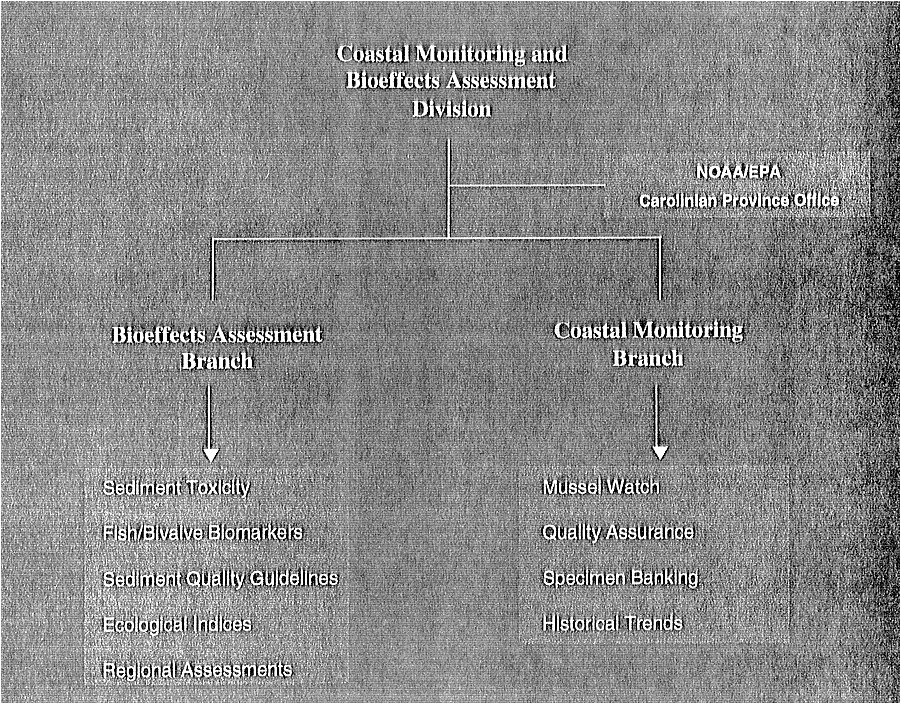

We do a number of things in the National Ocean Service that deal with the environmental contamination. Most is done in the Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment, and most significantly in the National Status and Trends Program where we monitor contaminants in the coastal areas to identify spatial and temporal trends, define spatial extent and severity of sediment toxicity and in situ changes in biota and ecosystems.

What we do is national in scope. The Arctic is an important part of our efforts only in the sense that there are some new emerging problems in the Arctic relative to contamination. The Arctic still is regarded as a pristine environment that is very rich in natural resources. There is very extensive petroleum development and production operation going on the North Slope of Alaska and we know that there is widespread occurrence of contaminants in nearly all aspects of the arctic ecosystem; more recently, we found some evidence of new generation pesticides widely distributed in the air, fog, seawater and the surface layer in the Bering Sea and Chukchi Seas.

I would like to address three issues relative to contaminants in the Arctic and what we have done about it. One important consideration is the occurrence of radionuclides,

particularly in animals of subsistence use in the Arctic. We have found that the typical consumption of caribou meat would add a very small amount of radiation dose, which is 0.0045 milliSievert. This is very small compared to what the natural radiation brings to the humans and, also, from some other anthropogenic source such as x-rays.

Now, this was based on the terrestrial food chain. In the case of the marine food chain, the impact from the consumption of subsistence foods is really minimal, almost negligible. We have also found that global fallout seems to be the primary means of distributing radionuclides in the Arctic.

Metal contamination is a quite different issue because it is very complicated. Here is an example of very large amounts of accumulated cadmium in the kidneys of walruses; this number, 147 to 204 parts per million, far exceeds an amount that is known to cause renal disruption which is about 50.

Now, if you look at this data there is obviously magnification in the food chain, and again, this number is fairly high compared to what we find across the country. We don't have data from the Chukchi Sea and very few data from the Beaufort Sea. One explanation proposed is that there is a zinc mine which is being developed in the Chukchi Sea and that probably provides a lot of cadmium. We do not have the sort of information that we would like to have to really know if this is the case.

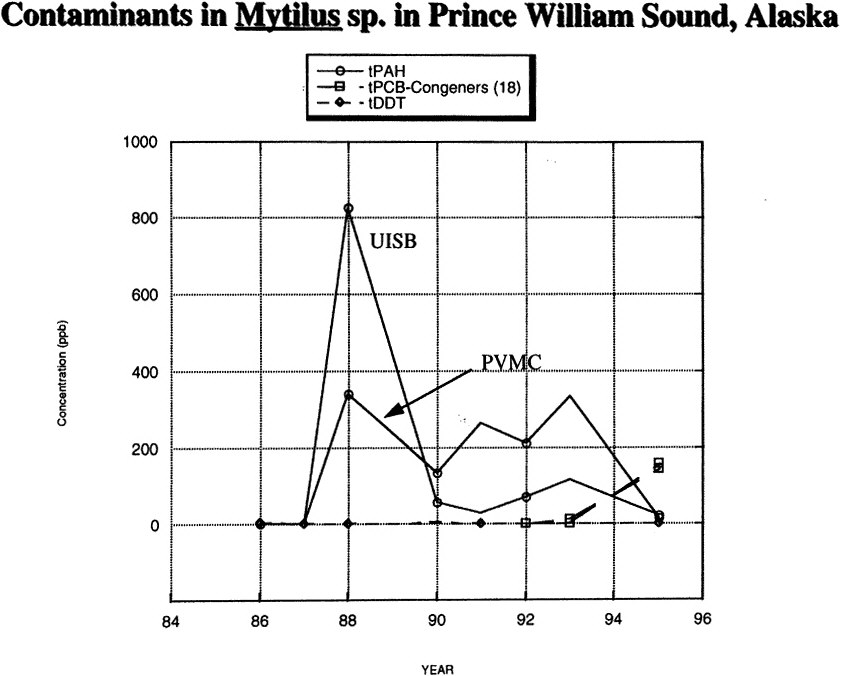

The third issue is very difficult only in the sense that we do not have adequate data on it, and that has to do with persistent organic pollutants. As Betsy Weatherhead mentioned, if you look at the AMAP report you will find essentially vacuums and gaps wherever there is supposed to be information about Alaska and the U.S. Arctic. However, where observations have been made we have found that there are PCBs and there are isomers of hexachlorocyclohexane, which is an insecticide in small amounts. But, if you look at the concentration in marine mammals in Alaska it is quite appreciable, but the levels are not very high. The question sometimes arises when people are looking at the concentrations of contaminants in other parts of the Arctic and then not relating to how the contaminants really are comparable or not comparable to the Alaskan area. Often they are making the connection that if terrible things are happening elsewhere, they ought to be happening here as well.

I think fisheries people have a lot more to say about this than I do. A few years ago there was a very large article in the Anchorage Daily News about the contaminants in the subsistence foods, but it was very realistic. Now, I am hearing that some terrible possible problems are going on. I think it behooves NOAA and other resource management agencies to try to relate as to what the real scientific data are and what the implications might be.

I have only shown five of many overhead transparencies included with this talk, but most of them are self-explanatory. You've asked each of us to say what we think NOAA ought to do: one of the important things that I would really like NOAA to set up a long-term multiparametric (meaning various contaminants) and multimedia (meaning air, water, sediment and biota) monitoring program in the Arctic. I have been proposing that for the last 5 years, so far with no success.

Questions/Discussion:

DR. OECHEL: How does this program interface or how should it interface with the Arctic Research Initiative?

DR. HAMEEDI: When the Arctic Research Initiative was developed 2-1/2 years ago, Ed Myers and I worked together. I was the one who put together the information from all the various NOAA elements in that draft that was then distributed. So, we are very involved in this one from the point of view of planning and so on.

Now, the other side of the coin is that in the last go-round of the Arctic Research Initiative funding, that had to do with these kinds of questions that I talked about, was zero. So, we sort of are there but sometimes not there.

DR. OECHEL: All that is lacking is money, right?

DR. HAMEEDI: I don't think so. I think it is a little more than just money.

Vision:

Healthy, safe and economically productive coastal and oceanic environments for present and future generations

Mission:

-

Protection of life, property and the environment

-

Effective management of the coastal zone and sustainable use of its resources

-

Assessment of the condition and productivity of coastal ecosystems

-

Reduced costs of pollution abatement and monitoring

NOS — Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment (ORCA): Missions

Provide Improved Capabilities and Information for Use in Coastal Management

-

Monitor Contaminants in Coastal Areas to Identify Spatial and Temporal Trends, Define Spatial Extent and Severity of Sediment Toxicity, and Describe in situ Changes in Biota and Ecosystems

(NOAA's National Status and Trends Program)

-

Provide Scientific Support to Manage the Cleanup of Spills and Discharges of Hazardous Materials

-

Evaluate Damages to Natural Resources from Spill and Discharges of Hazardous Materials

-

Conduct Comprehensive Strategic Assessments of the Multiple Uses of the Coastal Zone

NOAA's National Status and Trends (NS&T) Program

Long-Term Goals

-

Assess the status and trends of environmental quality in relation to levels and effects of toxic contaminants, radionuclides, and other sources of pollution in US marine, estuarine, and Great Lakes environments;

-

Develop diagnostic and predictive capabilities to determine effects of toxic contaminants, radionuclides, and other sources of environmental degradation on coastal and marine resources

US Arctic

-

Widely regarded as a pristine environment that is very rich in natural resources: oil and gas, fish, timber, coal, hard minerals, and wildlife; rapidly expanding non-exploitative activities, such as tourism

-

Continued petroleum production and development at a very high level (Prudhoe Bay, Kuparuk, Endicott, North Star, Liberty, Badami, and Alpine)

-

Widespread occurrence of contaminants, particularly ''persistent organic pollutants'' in all components of coastal ecosystems [long-range transport; "cold trapping" or "global distillation" hypothesis; scarcity of the hydroxyl radical]

-

Recent evidence of "new generation pesticides" [e.g., triazines, organophosphates] in air, fog, seawater, and surface microlayer in Bering and Chukchi seas

-

Heavy reliance on subsistence use of animals; 40 different species are harvested (marine mammals, caribou, anadromous fish, and eiders predominate)

Petroleum Hydrocarbon Pollution

NOAA's Involvement in OCSEAP, 1974-92

Fairly Good Information

-

Spilled Oil Trajectory Calculations — Diagnostic, Probabilistic and Real-Time Modeling

-

Spilled Oil Weathering Routines

-

Environmental Sensitivity Index [Spilled Oil Retention Potential] — Beaufort and Chukchi Seas

-

Movement of Oil in the Presence of Sea Ice

-

Knowledge of Environmental Constraints to Technology, e.g., Sea Ice, Permafrost, Seismicity

-

Exposure Characteristics, i.e., scale and timing

-

Nature of Biological Effects — Laboratory and Microcosm Experiments

-

Diagnostic Measures to Infer Petroleum Hydrocarbon Sources, e.g., LALK/TALK, PRIS/PHYT, N/P, FFPI, etc.

Radionuclides in Animals of Subsistence and Ecological Value

-

We have recently demonstrated that in the Barrow area:

-

Typical consumption of caribou meat, having 24-36 Bq/kg of Cesium-137, adds a very small amount (0.0045 mSv) to the average annual effective dose equivalent of ionizing radiation from natural (3.0 mSv) and other anthropogenic sources, such as x-rays, consumer products, and air travel (0.6 mSv)

-

Subsistence foods derived from marine food chains pose much smaller and negligible radiation dose; radionuclides in blubber, muscle, kidney, and liver of marine mammals are below detection or extremely low, less than 0.5 Bq/kg dw of Cesium-137

-

Global fallout appears to be the only significant source of radionuclides in the region

-

Cadmium in the Arctic Environment and Biota

|

|

Ag, |

As Cd, µg/g dw |

Zn |

||

|

(Sediment) |

|||||

|

SE Bering Sea (n=12) |

|

0.08 |

|

||

|

Off Yukon River (n=4) |

|

0.03 |

|

||

|

Norton Sound (n=13) |

|

0.09 |

|

||

|

Chukchi Sea |

|

No data |

|

||

|

North Slope (n=4) |

|

0.29 [NS&T "high" 0.54; ERL 1.2] |

|

||

|

(Walrus, n=509, prey species) |

|||||

|

Mya sp. |

|

6.8 [NS&T "high" 5.7] |

|

||

|

Serripes sp. |

|

0.7 |

|

||

|

Mactromeris sp. |

|

1.3 |

|

||

|

Tellinids |

|

2.7 |

|

||

|

Echiurus worm |

|

2.7 |

|

||

|

(Walrus kidney) |

|||||

|

1981-89, mean values |

|

147-204 |

|||

|

(Mammalian kidney) |

|||||

|

Renal disruption |

|

50 [LMW proteinuria] |

|||

|

Correlation with age? |

|

very possible, only weak correlation found |

|||

Persistent Organic Pollutants

-

A very sparse, almost inconsequential data base suggests that POPs (notably PCBs and HCH isomers) are widespread in the US Arctic; no discernible pattern can be surmised

-

POP concentrations in marine mammals is appreciable (e.g., ca. 0.5 µg/g of PCBs in seals and 5 µg/g polar bear) but considerably lower than reported high values elsewhere in the Arctic (e.g., 4 µg/g in seals off Russia, and 50 µg/g in polar bears in Svalbard). {Note: Mean level of PCBs in human adipose tissues is about 1 ppm, and ca. 4 ppm in those involved in electrical equipment repairs}

-

A somewhat muted concern in Alaska about the presence of POPs in subsistence food species three years ago (see Anchorage Daily News, June 19, 1994) has now blown into a major hyperbole (based on possibility of hormonal dysfunction, immune-suppression, porphyria, cancer)

What NOAA Should Do to Succeed:

-

Restate its policy and institutional commitment to addressing Arctic contaminant issues on a sustained basis

-

Develop a mechanism to ensure equitable participation by pertinent NOAA line offices and programs; given item #1 above, NOAA must establish a long-term, multi-parametric and multi-medium monitoring site — an "index site" — treat Barrow.

-

Build on its reputation of scientific excellence and trust in reporting of scientific results to the public — Reach Out and Communicate

-

Seek and implement collaborative interagency efforts that would be mutually beneficial

-

Take an active role in fostering bilateral and international accords, such as:

-

Assisting Russians in settling up a scientific program for prudent development of oil and gas resources in the Arctic

-

Seeking collaborative efforts with Norwegians on POP measurements

-

Ensuring effective and best available representation at international fora

-

Benefits of Comprehensive Environmental Monitoring off Barrow

-

Demonstrate NOAA's leadership in orchestrating a multi-disciplinary environmental monitoring program

-

Demonstrate feasibility of a comprehensive approach to environmental contaminant monitoring

-

Implement NOAA's existing quality assurance and quality control procedures in a multi-agency context

-

Provide opportunity to residents of the Arctic to participate in research and monitoring to assure them on the region's environmental quality, well-being of their traditional food resources, and health of the ecosystems they depend on for subsistence

-

Effective use of the region's facilities and talent in cooperation with State of Alaska and local government agencies

-

Serve as an important US contribution to AMAP, and fill a key void in existing contaminant monitoring sites in the Arctic

A View From The National Weather Service

Robert Reeves

I am Bob Reeves with the Office of Meteorology in the National Weather Service. You heard Dr. Friday's opening remarks. He has a lot of history with Arctic and polar issues. Unfortunately I cannot claim that same long history, although fortunately, maybe for the length of this presentation. I am counting on our people in the Alaska region for major contributions in the arctic contaminants area.

The NWS role with respect to arctic contaminant research is primarily one of data collaboration and support, and of course, there will be users of end products. There are some activities specific to the Arctic and I will highlight some from the Alaska region.

Ice pack location, density analysis and 3-day forecasts for all Alaskan marine areas are being done in the Alaska region. The analysis is based heavily on visible microwave and infrared digital satellite imagery from NOAA and defense polar satellites. The second one, high-resolution sea surface temperature analysis for the ice-free areas of the water in that region, and the hydrologic forecasts of the Jokulhalups which is the sudden release and flood of water from glacier-dammed lakes during the summer melt season. Moving right along to activities related to contaminant issues, and this may be a little bit of a stretch for us, is transport of contaminants in water bodies, and thus there is an interest in the ocean sea circulation.

NCEP is indirectly involved with contaminant transport and fate issues through its contribution of ice modeling efforts. Bob Brombine is here from NCEP. I am not going to try to review these because he will be here through the rest of the day to address those specific topics.

The Alaska region also supports some of the Department of Energy research along the arctic coast and the central interior. They are measuring atmospheric constituents, looking at contaminants and arctic haze in stratus. We receive some of their data from their meso networks and low-level wind profilers.

Stratospheric ozone monitoring—our people at the Climate Prediction Center are involved in that. I believe Walt Planet is here, and I will defer any comment or discussion about that area to Walt. And of course, a routine prediction of volcanic clouds is made in the Alaska region in our operations there.

Regarding key research strategies related to the Arctic, one of the things that Jim Kemper raised was long-term temperature variations and Dave Hofmann and Eddie Bernard have whetted our appetites with some of their illustrations this morning.

I would like to see a lot more of this kind of work. We talk about global warming and again there is some question about whether some of that is anthropogenic and whether in the rural areas you are actually seeing some of that warming. Some people feel that the tundra is dying. The permafrost is melting. Glaciers are melting, and there is a tremendous impact on animals and humans.

When you look at the total percentage of CO2 absorbed, the tundra takes 25 percent according to our people. So if the tundra is dying it is going to have some effect

on CO2 absorption. The NWS offices in Alaska are collaborating with staff at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks under a common initiative to work on mesoscale modeling in the Arctic. A couple of the models are being run there. They feel that much more needs to be done in modeling the Arctic atmosphere and boundary layer for such things as ice, snow, water cover tundra cover and permafrost layers.

Also, they feel to the extent that the course or grid models tend to miss mesoscale features which are recurring then this can have a negative feedback on our estimations of climate change. So, mesoscale modeling is an important area. The primary role for the Weather Service, when I use the term ''monitoring'' here, I am talking about observations, atmospheric observations primarily; mesoscale model development to help with the transport problem and data integrity. The issues of data quality and continuity I think are very important. Where we can have an impact in those areas is ensuring that these things are carried on and that maintenance of instrumentation is kept up, and that is my presentation.

Questions/Discussion:

DR. OECHEL: You mentioned the tundra dying, and I am not sure how accurate that is. Climate change will cause replacement of tundra by other vegetation types and species, but I don't know if dying is really an appropriate way to look at it. You are aware that the tundra historically in the recent geologic past has been a sink for carbon and that carbon is stored in the soils; the amount of carbon stored is about 300 billion metric tons. So, it is significant relative to the atmospheric CO2 levels; Over the last couple of decades it has shifted from a sink to a source, and the size of the source varies seasonally, but virtually every year for Alaska every year since the early eighties the tundra appears to be a source of CO2 to the atmosphere rather than a sink. So, it has shifted from that significant ongoing long-term sink now to a source.

DR. FRIDAY: Walt, are the quality of measurements on the changing from a sink to a source enough to indicate trends of any consequence, because this is one of the doomsday scenarios on global warming that has been postulated in the past, and I am curious to know if the data really support it yet.

DR. OECHEL: My personal opinion is that the data on long-term carbon accumulation are pretty good. They are spotty, but they are pretty good because they are based on C14 analysis and P profile. I think the data on measurement of fluxes that were made during IBP are quite good. Then from the eighties to current, we have a pretty good indication of the trend, the UV variability and carbon flux, and what all those data show together is that the long-term history is a sink of one-or-two-tenths of a gigaton per year for the Arctic.

In the seventies it was at least that or maybe a bit more. By 1982, areas that were measured were a source and through the late eighties it was source along the haul road, and comparisons were made at Barrow which I think were quite solid. That was a major effort and fairly sophisticated approaches in 1991-92, and there what you see is 1971-72

through 1974-75 was a strong sink; 1991-92 was a seasonal source just during the summer, and then if you add the winter losses of carbon, then the source is even larger.

I think we have enough data to say that the long-term pattern is one of a sink. The seventies it was a strong sink. The eighties to nineties it has been a variable source. The remaining questions include things like what is the ecosystem acclimation; what is the potential for ecosystem acclimation; how much ecosystem acclimation have we already seen; and what can you do with the record that we have of 10 or 15 years now to project into the future, and that is a big uncertainty.

DR. OECHEL: I gather from your presentation that there is more handshaking between the Arctic Research Initiative and your program than maybe some of the other programs; is that true?

DR. REEVES: I don't have a good feel for that. I just got a sense from Jim Kemper that he was wondering where the meteorology fit in from last year, but what I see in the guide from the booklet that was handed out, there is a lot of room for atmospheric involvement in this program.

NOAA's Arctic Contaminants Research

The NWS role with respect to Arctic contaminant research is primarily one of collaboration and support

Responsibilities of the NWS in the Arctic

Ice pack location, density analysis, and 3-day forecasts for all Alaska marine areas: Bering Sea, Bering Strait, Cook Inlet, Bristol Bay, Chukchi Sea, and Beaufort Sea, based primarily on satellite imagery.

High resolution sea surface temperature analysis for open water in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska, including Cook Inlet, Bristol Bay, Prince William Sound, and southeast Alaska.

Hydrologic forecasts of Jokulhlaups

Activities Related to Arctic Contaminant Issues

Transport of contaminants in the water bodies, thus there is an interest in ocean and sea circulation in the Bering, North Pacific, Beaufort Sea, and Chukchi Sea.

NCEP is indirectly involved with contaminant transport and fate issues through its contribution of ice modeling efforts (for shod and medium range forecasting), and forecast surface winds and surface currents that could be used for hazardous spill forecasts

-

Sea ice drift model —

-

Automated sea ice analysis —

-

Full sea ice model —

-

Sea ice thickness assimilation research with NASA —

-

Effects of ice on atmospheric circulations —

The Alaska Region support of Department of Energy research in Alaska along the Arctic coast and in the central interior. Arctic haze and stratus. NOAA special rawinsonde releases. DOE mesonets and low level wind profilers located near Barrow.

Stratospheric ozone monitoring using ground-based and satellite measurements No. Hemisphere Winter Bulletin published annually in April

Volcanic Cloud Predictions

Key Research Issues Related to Arctic Contaminant Inputs, Transport, and Effects from Natural Variability and Anthropogenic Influences

Long-term temperature variations impact vegetation and animal life dramatically in the Arctic. Because Alaska is warming, which causes the tundra to die, the permafrost to melt, and glaciers to melt, there is tremendous impact on animals and humans.

Improved Mesoscale Modeling

The NWS offices in Alaska are collaborating with the meteorology staff at the UAF under a COMET initiative to work on mesoscale modeling in the Arctic. Jeff Tilley is adapting the NCAR MM5 model to Alaska and is successfully running very early versions of the model on the UAF Cray and HP workstations. Peter Olsson is adapting the Colorado State RAMS to Alaska and is running it on the Cray. It is these projects we had in mind for support coming from the CIFAR.