Becoming Real Readers

Kindergarten Through Grade Three

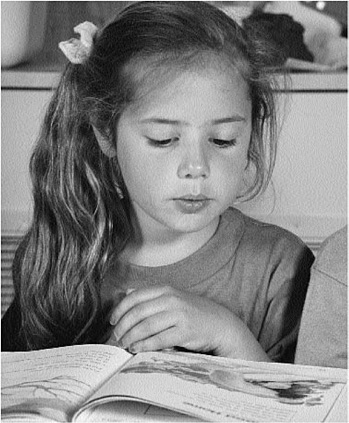

The mission of public schooling is to offer every child full and equal educational opportunity, regardless of the background, education, and income of their parents. To achieve this goal, no time is as precious or as fleeting as the first years of formal schooling. Research consistently shows that children who get off to a good start in reading rarely stumble. Those who fall behind tend to stay behind for the rest of their academic lives.

Supplementary tutoring and remedial instruction can help young readers who are doing poorly. But for all children indeed to have equal educational opportunity, then all children must have excellent curricula—right from the start—in their classrooms, from kindergarten through the primary grades. This chapter provides a view of children learning to read in kindergarten through third grade, using information from the latest research but made concrete through vignettes and activity examples. Our goal is to provide families and communities with a basis for understanding and helping out as teachers work with children who are becoming ”real” readers.

Individual Children

In any given classroom in America on any given day, there is a room filled with individual children who are likely to have very different educational strengths and weaknesses. All children simply do not learn everything at the same pace. Children also come to kindergarten and first grade with different kinds of preschool literacy experiences.

Most teachers are given a “scope and sequence” of curriculum skills that they should teach week by week—determined either by their districts or in

|

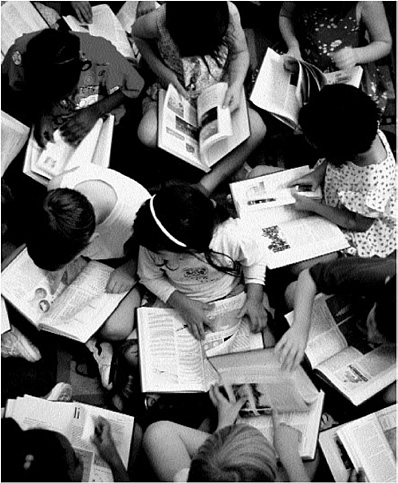

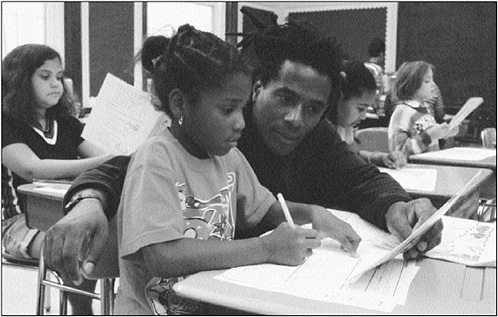

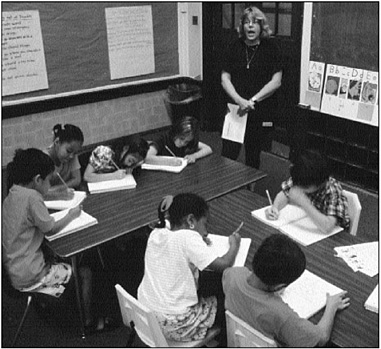

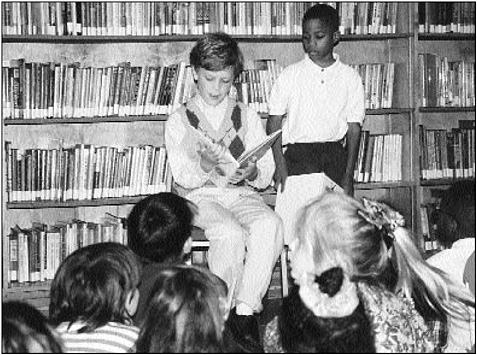

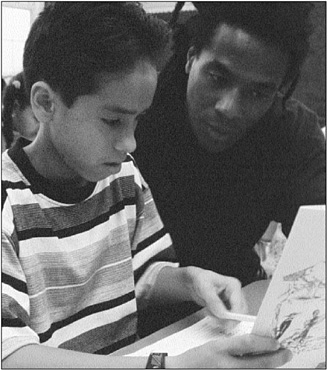

High-Quality Teaching: One Classroom To become real readers, children in kindergarten and the early grades need well-integrated instruction that focuses on three core elements: (1) identifying words using sound-spelling correspondences and sight word recognition, (2) using previous knowledge, vocabulary, and comprehension strategies to read for meaning, and (3) reading with fluency. Good teachers help children master these skills with an engaging variety of activities. In Mr. Carter’s first grade reading class, each student has a personal basket of books, chosen to match his or her abilities and interests. Bulletin boards offer children word attack strategies, with lists of spelling patterns and rhymes. Each child has a journal filled with interesting writing. Because this is a high-poverty population, the district has made a conscious effort to create small classes. This class has only 18 children—a good thing, considering that the children come from an array of linguistic backgrounds and cultures, including Somalia, the Philippines, Guatemala, and Vietnam. The room is bright and engaging, with various displays: photos of insects, alphabet letters, days of the week, colors, a tape recorder, and a little horticulture center with seeds and plants growing in the  |

|

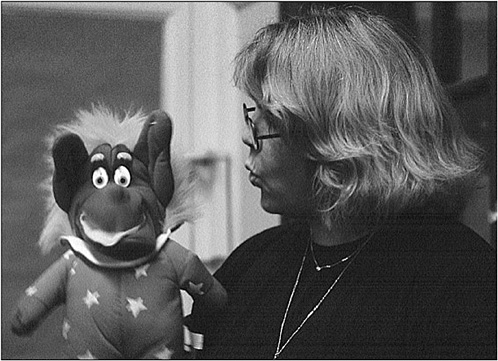

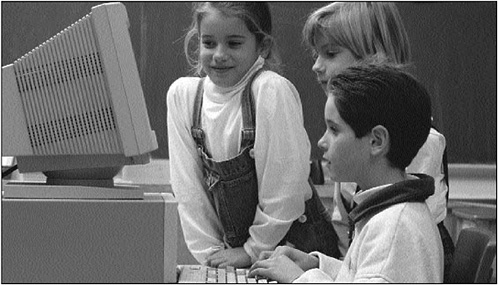

sun. Activity centers around the classroom are well organized, containing puppets, stuffed animals, props, paints, paper, and plenty of writing materials. But what is most inspiring is watching Mr. Carter teach. For about two hours during reading period, he tirelessly keeps the children moving in an upbeat and energized pace from one interesting and valuable activity to the next. When reading period begins, the children get their personal baskets of books and sit at their tables reading independently. Mr. Carter also has them read in pairs—shoulder to shoulder—or in small groups in circles on the floor. During this time, he takes the opportunity to move around the classroom and provide personalized attention. With one child, he reviews the previous day’s word attack lesson. With a small group, he sits down on the floor and begins asking questions, helping them make meaningful connections between the literature and their own lives. Now it is time for today’s word attack lesson. The children put away their baskets and gather around Mr. Carter at the board. Each child sits on the floor holding a personal eraser board and magic marker. Clearly these new tools bring an aura of importance to the small hands holding them. Perhaps it is the authoritative thick marker, or the teacher-like power to erase. Perhaps it is the power of having one’s very own tableau. Beyond being fun, the boards also give children privacy to make mistakes and easily correct themselves. Mr. Carter begins by reading a sentence he has written on the board. Certain parts of the words are covered up. When he comes to the word “kind,” he says it aloud, but what the children see is k___. He asks them to provide the missing letters. After various responses, correct and incorrect, he reveals the correctly spelled “kind.” He then asks children to write the words “find” and “mind” on their boards. He proceeds doing a similar exercise with a number of words. Now it is time for a class read-aloud time, in which children sit in a circle for two books, one fiction and the other nonfiction. Because it happens to be the end of the school year, both books are related to the theme of summer vacation. The students are engaged and eager to participate. They sit in an orderly way, enthusiastically raising hands to answer questions instead of calling out. (This is protocol that Mr. Carter requires.) Mr. Carter pauses frequently, asking questions about the characters, plot, and meaning of the text. He also makes time for the children to ask some questions of their own. At the beginning of the second hour, Mr. Carter gives a writing assignment. The children are to write a letter to a friend, describing their plans or hopes for summer vacation. When they are finished, they go to the computers to illustrate something from their writing. If time allows, they will then move on to their journals. Because the classroom has only six computers, he breaks the students into rotating groups. Mr. Carter moves easily among groups, checking on his students’ progress. Some children at the computer need encouragement. They don’t know how to go about illustrating their writing. He talks through some options with them. When working with the children who are writing, he praises efforts to logically sound out new spellings—even if their final product is incorrect. But when he sees students misspell previously introduced words, such as “find” (taught that very day), he is sure to make a correction. Casually picking up a book or a word card, he says, “Remember the last time we saw this word in a book, it was spelled this way.” For a student who is having trouble with the writing assignment because she obviously didn’t understand the story, Mr. Carter retrieves the book and asks an aide to read it again to the child. For another child, whose discomfort with the mechanics of holding a pen and writing gets in the way of even beginning to write, he assists by taking dictation. For children who have successfully completed the assignment before the others, Mr. Carter sets up groups of two, encouraging them to take turns reading to one another and polishing their newly finished creations. |

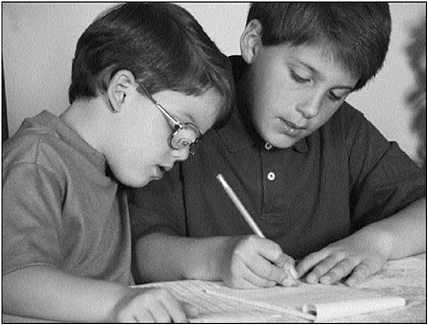

published reading programs. One major benefit of these materials is that they provide a year-long plan for instruction—an essential element for effective teaching. However, even the most well-equipped children may not move with equal ease through any preset sequence of lessons. Teachers must adapt and augment their lessons to meet the unique needs of every one of the individual children in their classrooms. Most children need a motivating introduction and a lot of repetition and practice in order for their emerging skills to become automatic.

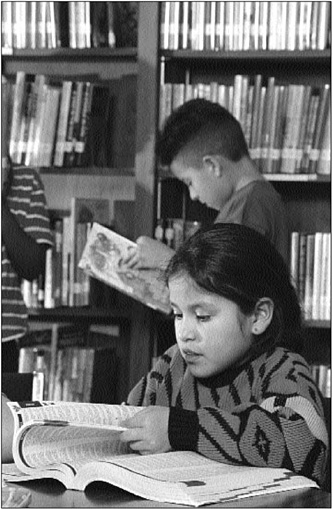

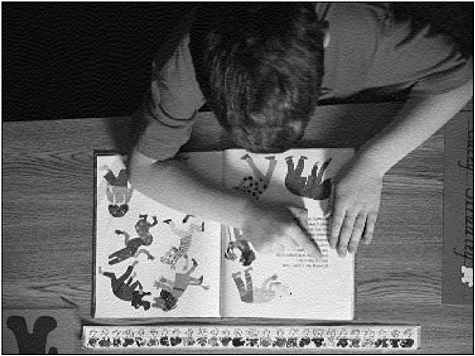

When children begin to read, they need the opportunity to read independently each day, choosing some texts themselves. These materials must be of high quality and of a difficulty level appropriate to the individual. Repeated readings of easy texts help children practice and assimilate what they’ve learned. Books that are more difficult give them a chance to move, and sometimes leap, ahead. Texts that appeal to their personal passions help them build a lifelong love of reading.

School leadership is responsible for making sure that reading instruction is coherent, that is, there is a consistent approach across the grades and that the teachers in the later grades know what the teachers before them have done.

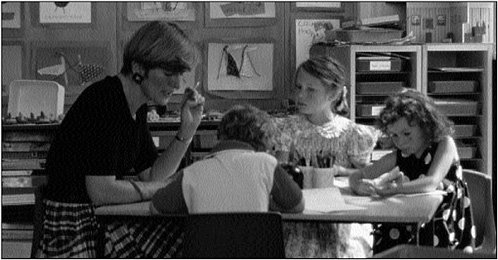

We teach in small groups, whole group, and one on one—depending on the needs of the kids. We read literature to the whole class. Then, when we do reading instruction, we may put three children together who need the same thing. It’s about finding out what children know and moving to the unknown.

Each child comes to school with a backpack. And in that backpack, each one has something different. Some have lots of experience with books and magnetic letters. Others have been living in an apartment with 15 people. What drives me to teach is watching what goes into those backpacks over the years.

—Emelie Parker

First grade teacher

Bailey’s Elementary School

Fairfax County, Virginia

The Kindergarten Challenge

One major goal of kindergarten has always been to help children become comfortable in a formal classroom setting. Indeed, it is a major adjustment. Five-year-old children who enter kindergarten must learn how to sit quietly, to share, to listen, to communicate cooperatively, and to do what is asked. Even in the most individualized class, they must make do with far less personal attention than they probably are used to. Helping children meet this emotional and behavioral challenge is extremely important.

But kindergarten must also prepare children to learn to read, and this must be a key priority. Children enter kindergarten with different preschool reading and writing experiences: some write with scribbling and others with letters; some have lots of storybooks in their past and recite them eagerly; for others, books seem pretty unfamiliar. Research consistently demonstrates that children need to enter first grade with good attitudes and knowledge about literacy. Otherwise, they will probably find first grade instruction inaccessible.

What Must Be Accomplished—Goals of Kindergarten

The delicate balance for the kindergarten teacher is to promote literacy in well-thought-out, appropriate ways. Two goals are paramount:

-

When children leave kindergarten, they should have a solid familiarity with the structure and uses of print. They should know about the format of books and other print resources. They should be familiar with sentence-by-sentence, word-by-word, and sound-by-sound analysis of language. They should achieve basic phonemic awareness and the ability to recognize and write most of the letters of the alphabet.

-

Kindergarten should help children get comfortable with learning from print, since much of their future education will depend on this. By the end of the year, kindergartners should have an interest in the types of language and knowledge that books can bring them.

In this following section we present activities for kindergarteners. As for the earlier sets of activities, the main purpose is to illustrate the concepts underlying reading instruction in kindergarten. We expect that the individual activities included will be helpful for most children; however, they are not a substitute for a comprehensive curriculum.

Activities and Practices For Kindergartners

In kindergarten, it is especially appropriate for instruction to be based in play activities. By singing songs and acting out stories and situations, children develop language skills, narrative abilities, and a comfort with using symbols, that is, the idea that one thing can “stand for” something else. These are key for learning to read. We describe a range of activities that teachers can use in their classrooms. Many of them incorporate play-based instruction.

Book and Print Awareness

To become successful readers, children must understand how books and print work. They should know the parts of a book and their functions and that the print on the page represents the words that can be read aloud. By kindergarten, they can begin to distinguish various forms and purposes of print, from personal letters and signs to storybooks and essays.

Activities

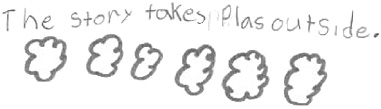

![]() Do dictation activities to help kindergartners understand that any thing spoken can be written. You can turn this into a major bookmaking project, collecting oral stories that children dictate, illustrate, and share with one another. And you can do frequent short dictations, writing down children’s captions or titles for their artwork, or writing their shopping lists for pretend play. As part of these activities, help children notice various aspects of how print works: text is read from left to right and top to bottom; words are separated by spaces; the end of a line is not always the end of a thought.

Do dictation activities to help kindergartners understand that any thing spoken can be written. You can turn this into a major bookmaking project, collecting oral stories that children dictate, illustrate, and share with one another. And you can do frequent short dictations, writing down children’s captions or titles for their artwork, or writing their shopping lists for pretend play. As part of these activities, help children notice various aspects of how print works: text is read from left to right and top to bottom; words are separated by spaces; the end of a line is not always the end of a thought. ![]()

Phonological Awareness

During the preschool years, most children spontaneously acquire some degree of ability to think about the sounds of spoken words, independent of their meanings: phonological awareness. In kindergarten, it is especially important to strengthen this initial insight, and especially to help children develop an awareness of the smallest meaningful units or phonemes that make up spoken words (a skill that is termed ”phonemic awareness”). This is a crucial step toward understanding the alphabetic principle (that phonemes are what letters stand for) and, ultimately, toward learning to read. ![]()

Activities

![]() Many of the activities described earlier for use with preschoolers (pages 47 and48) are also appropriate for kindergartners.

Many of the activities described earlier for use with preschoolers (pages 47 and48) are also appropriate for kindergartners.

![]() Play the game SNAP using shared sounds. It’s an excellent time passer during long car rides. One player says two words. If they share a sound, the other players say “snap” and snap their fingers. If the two words don’t share a sound, everyone is quiet. Take turns. Begin with first sounds and go on to middle and final sounds when the child can do the first sound well. For example,

Play the game SNAP using shared sounds. It’s an excellent time passer during long car rides. One player says two words. If they share a sound, the other players say “snap” and snap their fingers. If the two words don’t share a sound, everyone is quiet. Take turns. Begin with first sounds and go on to middle and final sounds when the child can do the first sound well. For example,

|

Player 1 says, “ball and bat.” |

The others say, “SNAP!” for the first sound. |

|

Player 2 says, “sand and book.” |

Everyone is quiet. |

|

Next player says, “run and tan.” |

The others say, “SNAP!” for the last sound. |

|

Next player says, “seed and beach.” |

The others say, “SNAP!” for the middle sound. |

Be prepared for things to get a little silly.

![]() Tell children that you are going to play a listening game with them. Give out four blocks or some other tangible item, like card chips or beads, that can be used for counting phonemes. Remember to count sounds, not letters. These are spoken words, not written ones.

Tell children that you are going to play a listening game with them. Give out four blocks or some other tangible item, like card chips or beads, that can be used for counting phonemes. Remember to count sounds, not letters. These are spoken words, not written ones.

-

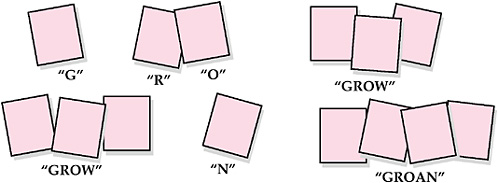

Say a two-phoneme word, such as “row,” and ask the children to repeat it. Then say, “I can divide the word ‘row’ into two parts: ‘r ’ and ‘o’. Let’s make this block stand for the ‘o’ part. We need both blocks together, ‘r ’ and ‘o,’ to make ‘row’.” Have the children do this with their blocks. In this exercise, whenever you refer to a particular phoneme, touch the block that represents that segment.

Next explain that a new word can be made by taking away the first block (the ‘r ’ part). Have everyone take away the first block, and ask what the remaining block “says,” namely the word “oh.” Then ask what will happen if the first block is put back. Help the children to realize that the blocks now represent the word “row” again.

-

Next explain that another word can be made by adding a new block in front of the “r.” This new block stands for “g,” so when “g” and “r” and “o” are put together, we get the word “grow.” Next, ask the children to add a block after the “o”; this new block stands for “n.” Help them to understand that the four blocks now represent the four phonemes in “groan.” Finally, have them remove the “n” block, leaving “grow” again.

-

After this introduction, tell children that you now want three blocks to stand for a different word, “lamb.” So now the first block is for the “l” part, the second block is for the “a” part, and the third block is for the “m” part. Now ask, “If I want to make the word “am,” should I take away one of the blocks or should I add another block? (Answer: take away the first block.) And if I want to make the word “lamb” again, what must I do? (Answer: put it back.) And if I want to make the word “lamp,” what should I do? (Answer: add a new block after the “m”.)

Repeat this exercise, sometimes first giving a word that requires removing a phoneme, and sometimes one that requires adding a new phoneme. Here are some words you can use:

|

Starting words |

Words requiring removal |

Words requiring addition |

|

late |

ate |

plate |

|

gray |

ray |

great |

|

pin |

in |

spin (or pinch) |

|

tore |

or |

store |

|

rice |

ice |

price |

|

care |

air |

scare |

|

rain |

ray |

train |

|

bad |

add |

band |

|

goat |

go |

ghost |

|

mall |

all |

small |

![]() Do a listening game in which you have children blend your pronunciation of onset (the first part of a syllable) and rime (the ending part) into a meaningful one syllable target word.

Do a listening game in which you have children blend your pronunciation of onset (the first part of a syllable) and rime (the ending part) into a meaningful one syllable target word.

-

Tell children that you are going to say a word broken into parts and that you need them to put the word back together. Begin by saying simple words aloud, pausing between the onset and the rime. At first, vary the onset and keep the same rime:

r … an

m … an

f … an

Then keep the onset and vary the rime. For example,

m … an

m … ice

m … ix

-

Expand the activity by saying a word and asking children to provide another that ends with the same sound—i.e., rhymes.

Language, Comprehension, and Response to Text

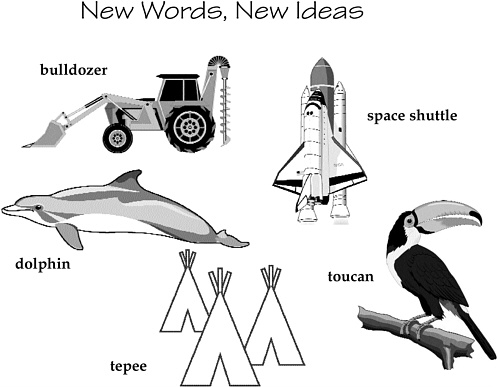

Texts can give us great ideas, entertaining stories, knowledge, information, and countless other riches. But children who lack vocabulary and a useful repertoire of general knowledge can barely take the first step toward the most basic understanding of the texts they encounter. How can they understand a science book about volcanoes, a fairy tale about silkworms, or a short story about Inuits if they don’t understand the words “volcanoes,” “silkworms,” or “Inuits”? What if they know nothing of mountains, caterpillars, or snow and cold climates? Kindergartners need the chance to build their general background knowledge and language if they are to understand and profit from the texts they will encounter.

Another important factor in understanding text is interest. Children need to be interested in books and print, if they are going to read enough to get good at it. One important goal of kindergarten is to motivate children to relate to books and print as a meaningful and worthwhile part of their lives.

Rich classroom discussions, thoughtful question-and-answer periods, fun, engaging activities connected to texts, high-quality storybook readings—all these have an important place in helping children move, day by day, toward understanding what they read, enjoying it, and becoming real readers. ![]()

Activities

![]() Help children develop the knowledge and vocabulary they will need to become successful readers.

Help children develop the knowledge and vocabulary they will need to become successful readers.

-

Take children on excursions and field trips to interesting places that will give them new domains of knowledge and vocabulary. For example, a class visit to a farm can be introduced and followed with rich class discussion about food and farming, in which you and the children use new words and concepts, such as “tractor,” “milking,” “plow,” “fields,” “planting.” Also, elicit individual conversations in which children have a chance to describe what they have seen.

-

Set up a sharing time when children can bring in objects or concepts of interest to them for discussion. Create an enriching conversational environment by responding to the sharer and expanding on his or her thoughts, inviting other children to participate.

Use the above opportunities to inspire classroom discussions—both in a one-to-one and a whole-class format. Affirm children in their efforts to express themselves, but also gently nudge them to be more precise in their vocabulary and syntax. Enhance their syntactic abilities beyond the usual “and then, and then, and then,” by asking questions that encourage them to use words like “because,” “after,” “since,” and “while” in their responses. If a child says, “I ate a red lollipop,” you might help him or her be more precise by saying, “But there could be two different red lollipops. Did you have strawberry or cherry?”

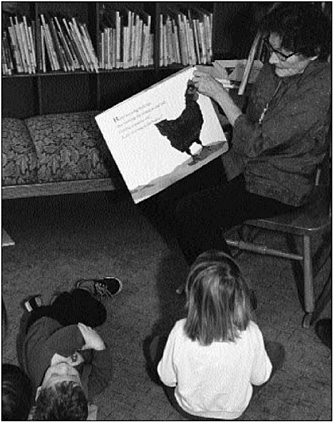

![]() Choose books and stories to read aloud that are about many different creatures, places, and things. Augment each selection with pictures, discussion, and especially other books and stories that allow the children to revisit and extend their new knowledge.

Choose books and stories to read aloud that are about many different creatures, places, and things. Augment each selection with pictures, discussion, and especially other books and stories that allow the children to revisit and extend their new knowledge.

![]() Sociodramatic play activities give children a chance to develop language and literacy skills, a deeper understanding of narrative, and their own personal responses to stories. Encourage children to retell, reenact, or dramatize stories or parts of stories they have read.

Sociodramatic play activities give children a chance to develop language and literacy skills, a deeper understanding of narrative, and their own personal responses to stories. Encourage children to retell, reenact, or dramatize stories or parts of stories they have read.

The possibilities for sociodramatic play are limitless and need not be related only to fiction. For example, one class decided to embark on a dinosaur dig after reading about dinosaurs. They cordoned off a small grassy area outside the school and began digging. One after another, children would finds sticks and stones that they would proclaim to be remnants of dinosaurs, such as triceratops or tyrannosaurus. The teacher helped them incorporate literacy by making signs for the digging area (“Dinosaur Dig—Do Not Disturb”) and by labeling the children’s findings. The endeavor led to further book reading about dinosaurs, discussions about science, and rich conversations.

Here are some tips for successful sociodramatic play:

-

Prepare the environment. Make sure children have the necessary materials, such as puppets, stuffed animals, building blocks, props, and writing materials (so they can use print in their play). The best classrooms usually offer thematic centers that appeal to student interests—such as a nature area, a puppet theater, a sand table decked out as a beach—along with books, stories, and trips related to the theme.

-

Provide ample time for children to create scripts and scenarios. Develop their background knowledge for the play setting

-

Encourage and guide rehearsals of dramatic retellings. Take part in the action yourself, demonstrating for children ways in which dramatization works.

-

Guide children in dramatizations that involve print—for example, a restaurant scene that requires a menu and a pad to write down food orders—reinforced by explanations of how menus work.

![]() Help children develop listening skills by offering books on tape and by playing games in which you call out oral directions and instructions for them to follow. You might also try call-and-response songs, such as the classic recording “Follow the Leader” by Ella Jenkins, in which children are asked to clap and beat out rhythms to music in various ways.

Help children develop listening skills by offering books on tape and by playing games in which you call out oral directions and instructions for them to follow. You might also try call-and-response songs, such as the classic recording “Follow the Leader” by Ella Jenkins, in which children are asked to clap and beat out rhythms to music in various ways. ![]()

![]() Good storybook reading is an interactive process that helps children explore language and develop many skills. Offer a variety of texts, nonfiction as well as fiction. Here are some effective techniques for reading aloud:

Good storybook reading is an interactive process that helps children explore language and develop many skills. Offer a variety of texts, nonfiction as well as fiction. Here are some effective techniques for reading aloud:

-

Have children ask their own questions about the story and respond to classmates’ questions.

-

Encourage them to follow the text with movement, mime, or choral reading.

-

Draw children’s attention to the forms of print, such as punctuation, letters, the space around words, chapter title placement, the line length differences between prose and poetry.

-

Provide repeated readings of the same story so children can gain mastery of the narrative, ideas, and language.

-

When reading chapter books to children, ask them to summarize before and after you read each chapter. “So where are we so far?” you might ask at the beginning of the session. And then at the end, “So what happened in this chapter?”

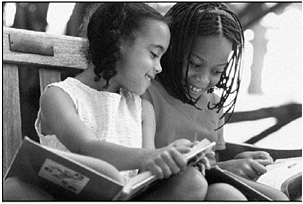

![]() Pair or group children together for shared book experiences. Or put children who have the same interests together and start book clubs in your class. In the book club format, help them read the same or similar books and discuss them with one another. Teachers might use parent volunteers to come in and help with reading or discussions in the clubs. Or children can bring home books to be read with parents and report on them the next day in their book clubs.

Pair or group children together for shared book experiences. Or put children who have the same interests together and start book clubs in your class. In the book club format, help them read the same or similar books and discuss them with one another. Teachers might use parent volunteers to come in and help with reading or discussions in the clubs. Or children can bring home books to be read with parents and report on them the next day in their book clubs.

![]() Give children access to a wide variety of reading materials.

Give children access to a wide variety of reading materials.

|

Connecting to Books It is the day before Thanksgiving break, and the kindergartners gather in a circle for story time. Whereas a few months ago, the children in her class had trouble sitting still, now they listen attentively, ready to answer Mrs. Harris’s questions. Today’s book is about a child whose grandmother has come from another country to visit for Thanksgiving. Much is made of the enormous hug that she gives her grandchild at the airport. Mrs. Harris pauses from the story. “Does anyone have relatives who like to give hugs when they come an visit?” Her purpose is to help children learn to connect information and events in texts to real life. Half a dozen hands shoot up eagerly. One by one, she hears accounts of hugging relatives—Mae, whose grandmother squeezed her tight when she went to Vietnam; Andre, whose aunt hugged him when she came from Guiana; Molly, whose grandfather hugged her when he came from Minnesota. After each child speaks, Mrs. Harris repeats the response, often asking the child to elaborate in some way, or add more detail. Finally, after listening to six or seven accounts, Mrs. Harris remarks, “Isn’t it interesting that so many families from so many different places all like to hug their kids. You seem to have something in common with the child in this story. Okay, let’s go back and read the rest,” she says and resumes reading. The children are quiet again, hanging on to her every word.  |

-

Give children guidance and suggestions for choosing appropriate reading materials that appeal to their interests and reading ability. Give them a chance to choose their own books in their class library, their school library, and their local public library. Help them to develop familiarity with a number of books and authors. For example, if they like a certain book, suggest that they look for another by the same author, or on a similar theme.

-

Help children develop familiarity with a number of types or genres of texts. Stock your class library center with a variety of materials, including storybooks, nonfiction, poems, newspapers, and magazines.

-

Other activity centers can include print from everyday life, such as take-out menus, this week’s cafeteria menu, seasonal toy catalogs, and class rosters that are kept current.

“At the beginning of the school year, one of the first things I do is send applications for library cards home with my students. Each child is issued a card, and I take the children to the library. I give parents a list of approved books. Many parents tell me they don’t know how to read well. If they can’t read to the child, I tell them to find someone who can.”

—Ethelyn Hamilton-Frezel

Kindergarten teacher

Dr. Ronald E. McNair Elementary School

New Orleans, Louisiana

Letter Recognition, Decoding, and Word Recognition

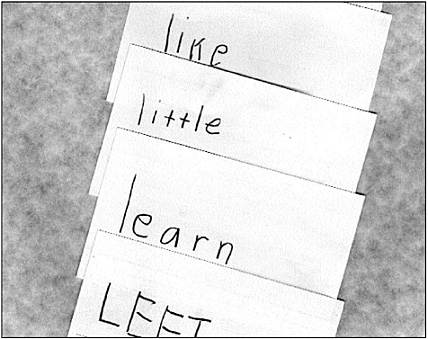

By the end of kindergarten, children should be able to name most of the letters of the alphabet, no matter what order they come in, no matter if they are in uppercase or lowercase. And they should do it quickly and effortlessly. They should begin to learn about letter-sound correspondence and to decode simple words. They should begin to recognize some very common words by sight. ![]()

Activities

![]() Establish a routine so that each child in the class has a day that is his or her Letter Day. On a given child’s day, put up his or her initials on a part of the bulletin or chalk board. For example, on Aaron Smith’s day, the teacher puts up the letters “A” and “S.” All day long, the children are to be on alert for words in their environment containing “A’s” or “S’s.” When they find one, they should whisper it to an adult. The adult will then make an announcement at the appropriate moment, saying something like “Jessica sees a letter ‘A’ in the science area. The word she sees is ‘ants’.” The teacher can then point to the poster of ants, then write the word on the chalk board.

Establish a routine so that each child in the class has a day that is his or her Letter Day. On a given child’s day, put up his or her initials on a part of the bulletin or chalk board. For example, on Aaron Smith’s day, the teacher puts up the letters “A” and “S.” All day long, the children are to be on alert for words in their environment containing “A’s” or “S’s.” When they find one, they should whisper it to an adult. The adult will then make an announcement at the appropriate moment, saying something like “Jessica sees a letter ‘A’ in the science area. The word she sees is ‘ants’.” The teacher can then point to the poster of ants, then write the word on the chalk board.

![]() Help children get increasingly comfortable with recognizing and naming all uppercase and lowercase letters of the alphabet. One fun way to do this is to play an adaptation of the old favorite game, I Spy. Reuse some piece of text that all children can have in front of them, for example, a photocopied paragraph in a book that matches one of the teacher ’s big books. Ask all children to focus on the text. Start the game by saying, “I spy with my little eye, seven small letter ‘t’s’.” In this way, challenge children to locate all the small letter ‘t’s’ in the passage. (Remember, they are not supposed to be reading the text, just looking for the letter and getting comfortable with recognizing it in uppercase and lowercase forms.) Allow children to take turns being the spy.

Help children get increasingly comfortable with recognizing and naming all uppercase and lowercase letters of the alphabet. One fun way to do this is to play an adaptation of the old favorite game, I Spy. Reuse some piece of text that all children can have in front of them, for example, a photocopied paragraph in a book that matches one of the teacher ’s big books. Ask all children to focus on the text. Start the game by saying, “I spy with my little eye, seven small letter ‘t’s’.” In this way, challenge children to locate all the small letter ‘t’s’ in the passage. (Remember, they are not supposed to be reading the text, just looking for the letter and getting comfortable with recognizing it in uppercase and lowercase forms.) Allow children to take turns being the spy.

![]() Show children that the sequence of letters in a written word matches the sequence of sounds they hear when the word is spoken.

Show children that the sequence of letters in a written word matches the sequence of sounds they hear when the word is spoken.

-

On the board, write a simple word that begins with a consonant. Direct the children to sound, blend, and identify the word. Swap the initial consonant with another consonant and ask them to say the new word. Demonstrate the sounding and blending of the letters for them. Repeat this exercise often. After children have mastered swapping the initial consonant, try replacing the final consonants. On any given day, however, it is best to focus on one letter position at a time. After children have had some experience, try the harder task of switching the vowel sounds.

|

Initial consonant swap: |

bat, cat, hat, mat, pat, sat, vat |

|

Final consonant swap: |

fit, fin, fib, fig |

|

Vowel sound: |

pat, pet, pit, pot or bit, bat, bet, but |

Tip: Don’t forget Dr. Seuss books, such as Green Eggs and Ham and One Fish Two Fish, which offer lively and fun prose filled with rhymes and word play that you can integrate into your lessons.

![]() Help children build their sight vocabulary. Try this word card game, a version of the parlor game Concentration. Make or gather two copies of 6 word cards, for a total of 12 cards (2 cards for each of 6 words). Shuffle the cards and lay them out in rows of three by four, face down. The first player turns over two cards and read each word that is turned over. If two cards match, the player takes the cards and gets another turn. If they don’t match, the player must put them back exactly in the same place, face down. Then the next player tries. Using his or her memory about the cards previously

Help children build their sight vocabulary. Try this word card game, a version of the parlor game Concentration. Make or gather two copies of 6 word cards, for a total of 12 cards (2 cards for each of 6 words). Shuffle the cards and lay them out in rows of three by four, face down. The first player turns over two cards and read each word that is turned over. If two cards match, the player takes the cards and gets another turn. If they don’t match, the player must put them back exactly in the same place, face down. Then the next player tries. Using his or her memory about the cards previously

revealed, he or she gets to turn over another two cards, trying to get a match. Play until all cards have been matched. Read all the words after the game. Play more than once to practice words. Add new words. Words like the following are good to start with, because they will be encountered frequently in books and are somewhat irregular in their spelling:

the

one

two

says

said

have

|

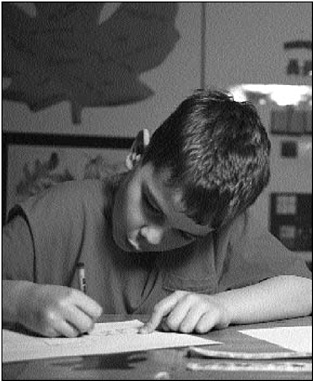

Writing Time  It is writing time, and the kindergartners are sitting in chairs with paper and pencil before them. Their assignment: to write about the weather that day. Mrs. Miller is moving about the classroom, coaching individual children in this endeavor. “Read to me, Amir.” Amir is now looking out of the window at the clouds. He picks up his writing and reads,“Today is cloudy. I hope it will snow.” On his paper is printed: Toda iz clody I hop it wil sno “Good,” says Mrs. Miller. She points to the word “toda,” and says. “I can figure this word out; this one is almost like how I spell it. She points to the word ”Today” on the blackboard. “What would you do if it snows?” she asks. “Make a snowman,” replies Amir instantly. “Why don’t you write that down and some other things you like to do in the snow. Then draw a picture to go with it. Make sure you put yourself in the story and in the picture. I want to see you in the snow.” Intrigued, Amir leans over his paper and continues working. |

![]() Help children learn to recognize common but irregularly spelled words such as “the,” “have,” and “two.” One excellent way is through familiar nursery rhymes. For example, write on the board and recite:

Help children learn to recognize common but irregularly spelled words such as “the,” “have,” and “two.” One excellent way is through familiar nursery rhymes. For example, write on the board and recite:

Hickory dickory dock.

The mouse went up the clock.

The clock struck one. The mouse ran down.

Hickory dickory dock.

Have children join in on the rhyme, and point to each word as it is read. Then write the word “the” and “The” on the board. Point to one line at a time and call on children to come to the board to touch the word “the” if it appears. Tell them that the word “the” is a word they see a lot when they read. Put the word on the wall with other words like ”the” that will occur freqently in text. These words should be taught as sight words so they are recognized instantly.

Spelling and Writing

Children need ample opportunity to write. Stock the kindergarten classroom with a variety of paper, writing utensils, and materials for book-making (glue, tape, stapler, book covers). Early in the kindergarten year, some children may still be scribbling and drawing pictures. By the end of the year, they will be independently writing most uppercase and lowercase letters, using invented spellings for many words, and working on a growing repertoire of conventionally spelled words. ![]()

Activities

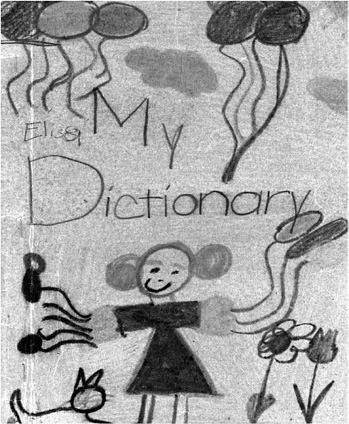

![]() Have children make their own letter dictionaries. Each child will need his or her own notebook, pencils, pens, crayons, markers, old magazines, safety scissors, and paste or tape. This is a year-long project.

Have children make their own letter dictionaries. Each child will need his or her own notebook, pencils, pens, crayons, markers, old magazines, safety scissors, and paste or tape. This is a year-long project.

-

Gather each child’s notebook and print each letter of the alphabet on the head of a single page—skipping some pages between each letter. Remember to print both uppercase and lowercase letters. When you are ready to proceed, pass out the books to the children, telling them that these books are going to become their personal letter dictionaries.

-

Have the children find conventionally spelled words to copy on the appropriate page. Encourage them to draw a picture of the thing, if possible, or to paste in a picture from an old magazine.

-

Use the dictionaries as a way to reinforce class activities and lessons with letters and words. For example, when it is Zakary Feinstein’s letter day, you might write some “z” or “f” words on the board and ask the children to copy them on the appropriate page in their dictionary.

Accomplishments of the Kindergarten Student

Kindergarten is a great time of preparation for the challenge of real reading. Toward this end, we list a particular set of accomplishments that the successful learner should exhibit by the end of kindergarten. Because of their importance, we present them in full, as published in Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children (National Academy Press, 1998). As with the list of accomplishments for the preschool child, this list is neither exhaustive nor incontestable, but it does capture many highlights of the course of literacy acquisition. Although the timing of these accomplishments will vary among children, they are the sorts of things that should be in place when children enter first grade.

|

Kindergarten Accomplishments

|

First Grade: An Important Year

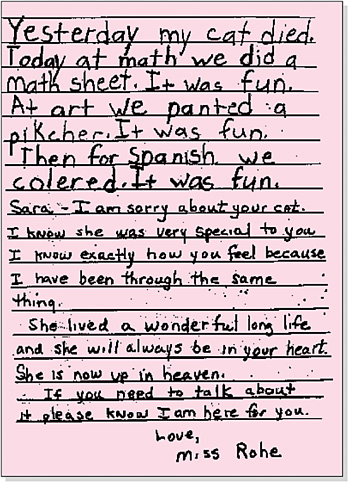

“I don’t think there is one best method of teaching reading or one best program. What I have done over my 27 years is pick what I think works and incorporate it. Every day, the children need to hear reading, and they need to be involved in the reading process. I do a lot of phonemic awareness with songs and games, as well as exposing them to a lot of print with labeling in the room. I do believe phonics is important. We also have a daily chit chat in which we talk to one another through writing. They write to me about their pets, their families, what they saw on television. Then the next day, I give them back a written response. It becomes an ongoing correspondence.”

—Susan Derber

First grade teacher

Sandburg School

Springfield, Illinois

Although becoming literate is a lengthy process that begins in babyhood, first grade is a most important year. First graders enter school expecting to learn how to read on their own. Their parents and teachers expect this as well.

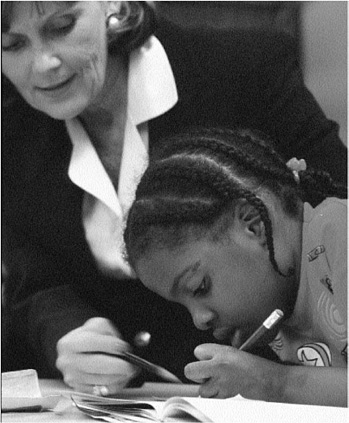

Anyone who has witnessed good teaching can attest that it is nothing short of an art, requiring remarkable talent, skill, and devotion. Teaching this age group, in particular, presents major challenges. In just about every school in America, some kids enter the first grade reading on a third grade level, whereas others are not able to reliably recognize all the letters of the alphabet. Teachers, most of them faced with more than 20 children, have to find ways to make sure that each child makes progress each day.

How do successful teachers accommodate the individual learning of so many very different first graders?

Sometimes they team with each other, even across grade levels, for small-group instruction suited to the abilities and interests of their students. Sometimes they set up groups within a class: the children benefit from working together, and the teacher is able to move around, focusing on a single group or taking time for one-on-one instruction with a struggling child. Sometimes teachers bring in volunteers or specialists to help challenge more advanced students or give individual help. Or they use whole-class activities designed to be interesting and successful even in classes with the most diverse mix of abilities.

All of these approaches—and many others—can work, so long as teachers avoid turning groupings into self-fulfilling prophecies that limit children. Always, teachers must sensitively monitor students’ needs and progress to keep up the challenge and feed their students’ curiosity, while avoiding frustrations and labels that can cause them to give up on themselves.

First grade is the time when children bring together the many language and literacy skills they have been attaining—book and print awareness, phonemic awareness, letter and word knowledge, background information about different topics—and start getting comfortable and quick with the conventions of associating letters and sounds. Ultimately, teachers must ensure that each child will not only read well, but also will enjoy reading and rely on it to learn new things as they move on with their lives. This is the year most children become “real” conventional readers, and most children depend strongly—some entirely—on teachers to guide this transition.

As in the previous section on kindergarten, in the following section we present activities for first graders in order to illustrate for family and community members, concepts underlying reading instruction. Many of the activities presented are ones expected to take place in the first half of the year. We expect that the individual activities included will be helpful for most children; however, they are examples rather than comprehensive curricula in themselves.

Features of Success

From parents to policy makers, an urgent question is: What does a good reading program look like?

There is no single answer, as each day, millions of children all over the country successfully learn to read under a great variety of approaches. What we do know, however, is that the most effective reading programs share certain common features, and that there are certain activities that all first grade children should be doing.

For a child to read fluently, he or she must recognize words at a glance, and use the conventions of letter-sound correspondences automatically. Without these word recognition skills, children will never be able to read or understand text comfortably and competently. Teachers help children with this hurdle by providing intense and intentional instruction on the structure of oral language and on the connections between phonemes and spellings.

In addition, first graders need intensive opportunities to read, each and every day, meaningful and engaging texts, both aloud with others and independently. In first grade and throughout the early grades, teachers should include explicit instruction on comprehension strategies, such as summarizing the main idea, predicting, and drawing inferences. In addition, first graders must have ample encouragement to write, even when this means using creative or inventive spelling.

|

First Attempts There’s a birthday in the family today. Larry’s little brother Evan has turned four. In the usual family tradition, everyone has gathered in the kitchen for a pancake breakfast. After the dishes are cleared, Evan is ready for birthday presents. “Happy birthday, Evan,” says Evan’s father, putting down two wrapped boxes before him. Evan makes a grab for his presents—ready to tear at the wrapping paper. “Hey, Evan—what about the card?” asks his mother. Evan tears open the envelope. After a struggle, he pulls out a birthday card.  “Hey, it’s a picture of a train!” he calls out. “I like trains.” Then he points to a few letters he knows. “There’s a ‘B.’ There’s an ‘O’.” Then, while looking at the words on the inside of the card, he rapidly sings the Happy Birthday song to himself. “Want me to really read the card?” asks his six-year-old brother. “I can read that card to you,” says Larry, who takes the card and unceremoniously begins to read in a slow, halting tone, sounding out almost every word, getting help from Mom with some words. “Ha…ppy B..irth…day and m..a..ny more. Can h…ard..ly believe…you are four!” “Why, Larry!” reply both his parents simultaneously—they had never seen Larry do anything like this before. They eye one another with shock. This is the first time that Larry has ever volunteered to read something. In the past, they’d wondered if he was really reading books or reciting them. But he has never seen this card before, and so now they are sure: he has become a real reader. Evan sets about tearing open his presents. One of his new treasures is a train set, the other is a book. Evan turns to his brother and says,“Hey, Larry—will you read my new book to me?” |

Finally, to help children understand the books they will encounter, reading classes—and all curricula in the primary grades—should help build their background knowledge and vocabulary in a rich variety of domains—from animals and the solar system to the ordinary workings of life, such as supermarkets and subways.

ACTIVITIES AND PRACTICES FOR FIRST GRADE CLASSROOMS

Continuing Phonemic Awareness, Letter Knowledge, and Book and Print Awareness

By first grade, many children have acquired some experience with phonemes in spoken language and with written letters, and they have a growing understanding about the uses and purposes of books and print. For children who need additional practice in these areas, some of the activities described in earlier sections of this book can be adapted with special content for first graders. Note that many of the following activities can be woven casually into daily first grade life, as children and teachers get to know each other. ![]()

Activities

![]() In this activity, you will have the children “break apart” and “put together” the syllables of words.

In this activity, you will have the children “break apart” and “put together” the syllables of words.

-

Tell children you are going to play the Name Game. Go around the class, saying children’s names, clapping and pausing with the syllables. For example, say “Sophia.” Then say it with pauses between the syllables, “So…phi…a,” while clapping once for each syllable. Do it again and ask children to join in. Go around the classroom, clapping out the syllables to various children’s names. Count the number of claps and point out that some names get just one clap, and other names have many. Do a few children’s names each day, during whole-class time.

-

Just as important, make sure that children also can put words back together from their syllable parts. For example, say “So…phi…a,” and ask the children to put the name back together. They should say, “Sophia.”

![]() When the children are confident and competent about the syllable-level activities, do similar activities working with phonemes, the

When the children are confident and competent about the syllable-level activities, do similar activities working with phonemes, the

smallest units of speech. Have children break apart and put together the separate phonemes of simple one-syllable words.

-

Try connecting this activity to the personality of classmates. For example, use picture cards that represent simple one-syllable words and have each child pick a favorite card. Now, call on a child to hold the picture card up while you say the word. Then say it again, but this time with pauses and claps between each phoneme. For example, Sophia has a picture of a star. You say, “star,” then you say each phoneme, “s…t…a…r,” with a pause and clap for each. Let the class repeat it after you, or let Sophia pick other children to break the word apart.

|

The Beauty of the Alphabet “It’s not just drill and practice so kids can learn how to read good stories,” says Ms. Jones, a first grade teacher for more than 10 years. “Sure, I love reading with children—it means the world to me. But the alphabetic principle is wonderful thing too, in and of itself.” She is talking to a young woman, a student teacher who appears about 20 years old. This is her first week on the job. Fresh from college, she has a passion for children’s literature, and a respect for the necessity of spelling and phonics lessons—but hardly a love of it. One suspects she sees the alphabetic principle as a sort of medicine that has to be swallowed, rather than something that could be celebrated and loved. “Imagine,” says Ms. Jones. “First, you’re just a young child and all the language you hear is a mysterious swirl of sound, and the words in your picture book are just little black marks. But then one day, you notice that there are some small sounds—phonemes—that you hear over and over again in different ways in different words around you. Take for example the “m” sound. It keeps coming up. You hear it in ‘mommy’…‘mailman’…‘milk’.” “Then you start to realize that you can manipulate phonemes yourself to make up all kinds of words. You can switch ‘bat’ into ‘cat’ and ‘cake’ into ‘bake.’ Now you’ve got phonemic awareness.” “Then you learn the letters of the alphabet. You’ve got these 26 lovely figures to record all these small sounds. Now you’ve got spelling or orthography. Even more thrilling: you can use those letters to recover the sounds that someone else recorded for your reading. Now you’ve got decoding and phonics.” “What an amazing system our alphabet is—and no one even really knows who invented it! But with the alphabet, everyone can read what anyone else has written, even people who do not know each other.” “That’s some way to look at it,” replies the student, clearly dazzled. “You’re darn right it is,” says the teacher. “This is the gift I give children—the alphabetic principle. And that’s why I love being a first grade teacher.” Ms. Jones walks off to her next class, leaving the student teacher standing amazed and a bit wide-eyed, listening anew to the sounds of children’s language echoing through the hallways around her. |

-

On another day you and the child might keep the picture concealed at first. Together, say the phonemes, “s…t…a…r,” with pauses between them. Ask the classmates to put the word together, rewarding them by showing the picture. Eventually, work on elaborations by getting the children to identify their mystery word in a sentence. For example, say “I looked up and saw the first s…t…a…r of the evening,” and Sophia should answer by saying “star,” and showing her picture.

![]() As an elaboration of the letter dictionaries described in the kindergarten section, have each child make a personal alphabet file with 26 folders—one for each letter of the alphabet. They can make the files with folded construction paper. Have them write the letters, both upper- and lowercase, on index cards in each file. (The files can be kept in a box in the child’s desk or cubby.) Over time, have them put names, other words, and pictures into the appropriate letter file. When new words come up in vocabulary lessons, reading, or other activities, ask the children to add them to their files. (An alternative to this is the use of an index card box. Each child has an index card box with dividers for each letter of the alphabet. Children put words, names, pictures on cards and file them under the appropriate letter.)

As an elaboration of the letter dictionaries described in the kindergarten section, have each child make a personal alphabet file with 26 folders—one for each letter of the alphabet. They can make the files with folded construction paper. Have them write the letters, both upper- and lowercase, on index cards in each file. (The files can be kept in a box in the child’s desk or cubby.) Over time, have them put names, other words, and pictures into the appropriate letter file. When new words come up in vocabulary lessons, reading, or other activities, ask the children to add them to their files. (An alternative to this is the use of an index card box. Each child has an index card box with dividers for each letter of the alphabet. Children put words, names, pictures on cards and file them under the appropriate letter.)

-

Check each child’s ability to recognize and print the letters. Create activities to send home daily for any child who is still having trouble.

-

Build enthusiasm by treating the words as collectibles. Give children words or pictures for the files as rewards. Ask children to bring in a favorite word from home (one that a family member helps them write and illustrate) and add it to their folders. Set up a bank for children to trade or borrow words or pictures for their files.

-

Use the files in your lessons. For example, try a hunt, asking each child to find all the animal words or pictures in their file that begin with “m” or all the toys that begin with “b.” Have the children make an index sheet for their file, writing on it all the words they have that match the hunt’s criteria. Pair the children up and let them find a few words they can trade with each other to copy into their file and put on their index sheet.

![]() Have a different child each day help you pick something to read to the class.

Have a different child each day help you pick something to read to the class.

-

Gather many different kinds of written texts to choose from: a book (or part of one) from the class library or from home, a “wordy” comic book, an entry from a children’s encyclopedia, the school lunch menu for the week, the weather report from the daily paper, an article from a children’s magazine, the riddles from the Sunday comics, the Saturday morning listing from a TV guide, the monthly event calendar from the school or some other community organization, a menu from a local favorite restaurant, a recipe, a shopping list, a story written by a child, directions for playing a board game, a class roster, a report card form, a preprinted standardized test.

-

Ask questions that will help the children discuss the meaning of what is read but also to notice the different structures and conventions. For example, you are supposed to get all the food items mentioned on a shopping list, but not on a menu! How do you know what day the 11:30 listing in the television guide is for? What kinds of printed material tell you who wrote it and where is this information shown? What’s the same about a riddle and a test? What is different? Which kinds of printed materials are only a part of a whole, and how do you find that out? How does the table of contents work? What is supposed to be fact and what is fiction, and how do you tell?

![]() Make a copy for each child of some text you have just read to the class, but put on the top a direction like “Find and underline all the

Make a copy for each child of some text you have just read to the class, but put on the top a direction like “Find and underline all the

words that use the letter ‘w’.” Give them a chance to talk about the different ways the letter is printed, noticing the differences between uppercase and lowercase and the different design or fonts that appear. Then, have the children circle the words that begin with the target letter and put their finished and corrected copies in their alphabet files for that letter, ready to be used for hunts and trades along with the other words in folder for that letter.

Decoding, Word Recognition, and Oral Reading

During first grade, the emphasis is on moving from pretend reading to conventional reading, relying less on others to read, and more on oneself. By the end of the year, every first grader should be able to read aloud with comprehension and reasonable fluency any text that is appropriately designed for the first grade, at least on a second reading. A book that is appropriately designed for the first half of first grade should be read with reasonable fluency and comprehension the first time through. By now, they are decoding accurately any phonetically regular one-syllable word, and they are able to rely on the alphabetic principle to attack unknown words. They also should be able to recognize common, irregularly spelled words by sight (e.g., “have,” “said,” “where,” “two”).

Across the days and weeks of the school year, there should be a clear plan for when new curriculum elements will be introduced—with sufficient time for intentional and intensive treatment by the first grade teacher. Just as important, children need ample time to explore and practice, so that what they have learned becomes easy and automatic.

Books and kits, as well as district-, school-, and teacher-made materials, offer many activities for first graders. As always, different children may be concentrating on different elements at different times. (The following are examples of valuable whole-class activities that can easily complement any teacher ’s approach to literacy instruction.)

Activities

![]() Making Words—Give each child a set of 26 letter cards, with corresponding uppercase and lowercase letters printed on either side (vowels in red, consonants in black). Here’s how to work with them:

Making Words—Give each child a set of 26 letter cards, with corresponding uppercase and lowercase letters printed on either side (vowels in red, consonants in black). Here’s how to work with them:

-

You announce and display the letters for the day: one or two vowels and three or more consonants.

-

The children pull the same letters from their own set of cards.

-

Now you call out words for the children to make—at first a simple two-letter word, and then succeeding words with more letters. In this way, children practice spelling and reading 12 to 15 additional words each day. One at a time, the teacher displays the correctly spelled word, taking care to point out letter-sound correspondences and spelling patterns.

-

The highlight of this routine is the mystery word—one that the children must discover on their own by using all the preselected letters. As part of the activity, the teacher helps children explore new words, sorting by various spelling or phonetic features, such as word families, rhymes, common vowel and consonant combinations.

Call out words

an

in

at

rat

Nat

tan

tar

tin

ran

ant

art

rain

Mystery word:

train

Making words is a fun and engaging activity that also gives teachers the opportunity for explicit instruction on specific spelling-sound relationships and the alphabetic principle in general. As each new word is displayed, children can correct themselves by comparing their spelling with the teacher ’s. Struggling children benefit from working with a limited number of letters at one time. Also, the activity is inherently motivational: children at all levels can experience both success and instructional challenge as the lessons get more complex.

One study found that first grade children who used these activities showed significant improvement in their reading abilities. ![]() Some students were even able to read fifth and sixth grade passages. This is particularly noteworthy, since teachers and parents alike often worry that whole-class instruction will slow down higher-achieving students. This clearly need not be the case.

Some students were even able to read fifth and sixth grade passages. This is particularly noteworthy, since teachers and parents alike often worry that whole-class instruction will slow down higher-achieving students. This clearly need not be the case.

![]() Word Wall—Select five words each week from a phonics lesson, a new book, or from the children’s writing. These words are posted on the word wall and, as a whole group, the children practice reading and spelling them with daily chanting, clapping, and writing routines. Save time for the children to add the words to their alphabet files. New words are added weekly, maybe at the suggestion of different children.

Word Wall—Select five words each week from a phonics lesson, a new book, or from the children’s writing. These words are posted on the word wall and, as a whole group, the children practice reading and spelling them with daily chanting, clapping, and writing routines. Save time for the children to add the words to their alphabet files. New words are added weekly, maybe at the suggestion of different children.

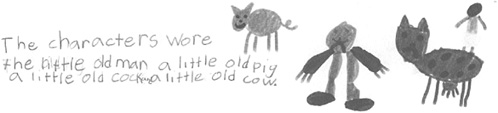

Language, Comprehension, and Response to Text

By the middle of the school year, first graders should be readily talking and writing about new texts they are reading. They are learning how to summarize, how to locate the main ideas, and how to make connections, both factual and emotional, to life and to other reading. They are beginning to draw inferences from text—understanding what is not stated explicitly, why something is funny, and what will probably come next. In short, they are becoming readers—building an interest in various types of books, as well as increasing comfort with the ideas, information, enjoyment, and language that print can bring them in their everyday lives.

By the end of this year, first grade children should be reading and comprehending both fiction and nonfiction that is appropriately designed for first-grade level. They have an expanding language repertoire, and they should be spending at least 10 minutes reading aloud to someone each day.

Research shows that, with daily encouragement to read, practice, and enjoy books, students can improve their fluency, word recognition, and comprehension skills. They also gain motivation. For these purposes, children need high-quality materials, including a range of texts selected for their unique interests and abilities. ![]()

Activities

![]() Give children the chance to thoroughly master more difficult texts through repeated readings. Most first graders love to read the same books over again, particularly if they are good ones, so don’t be afraid of repetition.

Give children the chance to thoroughly master more difficult texts through repeated readings. Most first graders love to read the same books over again, particularly if they are good ones, so don’t be afraid of repetition.

-

Choose books that children know and enjoy and set up various rereading arrangements such as whole-class, small-group, and individual rereading assignments. Remember to treat various small groups sensitively, depending on the ability of the students. For example, proficient readers can take turns reading parts of the book in a “round robin.” A slower group can read an easier book “round robin” style, or a teacher or aide can read the same book aloud, letting the children take turns reading the last word of each sentence.

-

You also may wish to send children home with a book to reread with a parent, older sibling, or other caregiver. So that the child has a trophy for her efforts, ask the caregiver to write a note back, for example, with comments about what he or she liked about it. The next day, during whole-class time, have the children do a choral reading. Ask them, “What did the people at home think of this story? Were you surprised at their reaction?” Draw them out on their impressions.

|

Bringing It All Together with Hot Cross Buns “What does lukewarm mean?” asks Alex. “Something that is between hot and cold,” replies Ms. Cane. “That’s just plain warm. I want to know about lukewarm.” “Well, it’s a special kind of warm …” “Where is it on the thermometer?” “Umm, well, really, you feel it on your skin and …” “Why? and why not just say warm?” Today is hot cross buns day in Ms. Cane’s first grade class, and Ms. Cane loves it. She loves the controversy over the word “lukewarm.” She loves the enthusiasm that the project stirs. And she loves the fact that in this single activity she can integrate so many of her first-grade reading goals. The recipe forces the children to explore syntax. It helps them build their vocabularies. It requires word attack strategies. It demands their comprehension. And finally, hot cross buns give the class a chance to work as a team on creating something wonderful together—all thanks to their reading skills. Soon, the classroom looks something like a bakery. Ms. Cane has brought in a stack of cookbooks, measuring spoons and measuring cups, mixing bowls, flour, sugar, and other ingredients. The children are gathered around in a circle and each has a copy of the recipe. Some children have volunteered to read the ingredients, while others get to hold the cooking equipment, showing how they would carry out the recipe’s instructions. Not long after the class is resolved on the issue of “lukewarm” comes a spirited discussion about “flour” versus “flower.” In both instances, Ms. Cane settles the issue to her satisfaction, but makes a note to herself that she must casually bring these words up again later to be sure that the children have understood. Now it is Julie’s turn to read a sentence of the recipe. “Beat throughly,” she says. Ms. Cane congratulates her on reading the word “beat” correctly. At her prompting, the class chants, “When two vowels go a walking, the first one does the talking.” “But Julie, let’s take a look at the second word of that sentence,” says Ms. Cane. “It’s not ’thr’ like in ’three.’ Look more closely. There’s a vowel between ’th’ and ’r.’ Ms. Cane reads the word “thoroughly” in the conventional way, exaggerating and slowing down the sounds. The class repeats it after her. “Any idea what it means?” The class offers a lot of guesses about beating speed, but finally, Julie says,“All the way through.” “Exactly!” praises Ms. Cane. “Now let’s figure out what it means to beat something all the way through.” The class now talks about mixing something so well that you can’t see the separate ingredients. One person misses this part of the discussion. It’s Julie, who is looking away with a pout, quietly muttering “Throughly. Like I said. All the way through.” She says it over and over, unwilling to let go of her original word. A few minutes later, the class reads the recipe once again. This time, Julie says the word correctly. About two hours later, Julie encounters the word again. This time she reads the word correctly, confiding to Ms. Cane,“The first time I saw this word, I thought it was like ‘three.’ But there’s an ‘o’ before the ‘r’. See?” “Oh, very good, Julie,” replies Ms. Cane, who graciously treats this as a new and valuable revelation. |

|

Hot Cross Buns 2 packs active dry yeast 1/3 cup lukewarm water 1/3 cup warm milk 1/2 cup oil 1/3 cup sugar 3/4 teaspoon salt 3 1/2 cups flour 1 teaspoon cinnamon 3 eggs 2/3 cup currants 1 egg white 1 cup special sugar Put the yeast in water until it gets soft. Meanwhile, mix together the milk, oil, sugar, and salt. Sift together the flour and cinnamon. Stir the flour mixture and the milk mixture together to make dough. Crack the eggs. Beat thoroughly. Add eggs to the dough. Beat thoroughly again. Add yeast and currants to the dough. Cover up the bowl and put it in a warm place to rise until the dough is two times as big as it started … |

![]() Surround class reading sessions with discussion and activities to help children develop their comprehension and vocabulary skills.

Surround class reading sessions with discussion and activities to help children develop their comprehension and vocabulary skills.

-

Prereading Activity Help children develop background knowledge and vocabulary they need to understand the text they are about to read. Find related text and information to share with them and have them do projects and other activities that will enrich their understanding of the concept, setting, or topic of the new text.

Look for new, unusual words in a story and discuss them together. Ask children to use the new words in another sentence. Talk about words that are synonyms or antonyms of the new words. Ask, “Could you say the same thing another way?” “How would you say the opposite?” Put the new vocabulary words on your word wall or in the children’s alphabet files.

-

Reading While the class is reading a story, be sure to orchestrate pauses for questions and discussion that will help comprehension.

-

Make children feel comfortable enough to ask their own questions. Some of the conventions of written language can cause problems for a young reader. Imagine the child who has just learned to tell time and then encounters the

-

sentence, “The family waited three long hours.” “Isn’t an hour always 60 minutes?” he asks. “How can one hour be any longer than another?” During the class reading, the teacher can take a moment to lead the children to explain that the author added the word “long” to tell us how the family felt while waiting. And yes, an hour always contains 60 minutes.

-

Teachers don’t have to hold off to the end of the story to ask their questions either. Help children build their comprehension skills by encouraging them to

-

compare and contrast

For example, “Toad was worried about his garden. But how did Frog feel about it?”

-

predict

For example, “What do you think Toad will do next?”

-

ask why and how

For example, “Why did Frog and Toad want to tie up the cookies with string?” Or “Why did they give their cookies to the birds?”

-

check their understanding of the sequence

“What happened after Toad woke up from his dream?”

-

-

After Reading

-

Summarize: discuss issues of plot and lead children to summarize what happened in the story. With children’s input, make a list of all the plot points on the board. For nonfiction, make a list of all the major facts or ideas that the text contained.

-

Develop character understanding: ask questions about the motives, interests, and concerns of real or fictional characters in their texts. For example, “Even though Toad was doing great and wonderful things in his dream, he was unhappy. Why?” Children may answer, “Because he missed his friend, Frog.” Help them to go further. Ask what this tells us about Toad. (That he is a character who cares about friendship more than glory.)

-

Relate texts to their own lives: encourage children to make connections between the texts and themselves, their homes, their neighborhoods, their feelings and aspirations. If children read an illustrated essay about animal tracks, ask them to talk about the animals and birds in their backyard or neighborhood, and what sort of tracks they might see. The discussion can go in many personal directions from here. You might ask children what traces they leave behind when they take a walk. Or the class might consider the lives of scientists who study animal tracks and whether or not this might be an interesting field of work.

-

Give children a writing or drawing assignment connected to what they have read. They can do this in groups, in class, or at home. You might have children do a book review, or ask them to write a letter to the author, explaining any feelings or insights about the author ’s work. To get children started, ask them if they think the author expressed himself or herself very well and why. Ask if the story could have been improved and if there was something else they wish the author had added to his or her work.

Another creative approach is to have students write and illustrate an advertisement about the book, designed to appeal to the next year ’s class. Ask the class if they think other children might like the book and why, and suggest that they include this information in their advertisement. Help them to come up with slogans and a dramatic or enticing scene from the book that would work well for illustration in their advertisement.

“Kids are natural question askers. But they don’t always know how to ask the nitty gritty questions you need to ask to understand the meaning of literature. They’ll ask superficial questions, like what color a character’s dress was. With the reciprocal teaching approach, I model for them and show them the kinds of questions they need to ask. I might start with sequence, asking what happened first in a story. Then I move on to comparisons, asking what is similar or different between past stories and the one we’re reading now. With fairy tales and nursery rhymes, I ask them to find similar themes. If you don’t show them, they never learn. They need to hear it, see it, and try it themselves.”

—Susan Derber

First grade teacher

Sandburg School

Springfield, Illinois

Spelling and Writing

By the end of the year, first graders should be correctly spelling three- and four-letter short vowel words. They are composing fairly readable first drafts, paying some attention to planning, drafting, basic punctuation, and correcting. Also, they are increasingly comfortable with a wide variety of writing formats: stories, descriptions, letters, and journal entries, as well as illustrations and graphics.

It is important for parents and teachers to understand that invented spelling is not in conflict with correct spelling. On the contrary, it plays an important role in helping children learn how to write. When children use invented spelling, they are in fact exercising their growing knowledge of phonemes, the letters of the alphabet, and their confidence in the alphabetic principle. A child’s “iz” for the conventional “is” can be celebrated as quite a breakthrough! It is the kind of error that shows you that the child is thinking independently and quite analytically about the sounds of words and the logic of spelling.

Yes, first grade children should be expected to correctly spell previously studied words and spelling patterns in their final writing products. But experimenting with spelling in the primary grades provides an invaluable opportunity for new readers to understand and extend their lessons on letter-sound and sound-spelling relationships. The combination of invented spelling and well-designed instruction over time ensures that their independent spellings of new words will become increasingly correct even as it makes studied words easier to remember.

Activities

![]() At the beginning of first grade, the challenge of writing something all by oneself is brand new to many children. Start them out with a topic that is familiar and manageable. Tell children they are going to write a book about themselves. Explain the concept of a work in progress, and provide each child with paper and a folder in which they will keep their work. Tell the students that, when all the pages are finished, they will put them together to make a book. Show them where you are keeping the files when they are not in use.