2

Background

NEED FOR A REDESIGNED PROCESS FOR PROGRAM ELIGIBILITY

The Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program (Title II of the Social Security Act [the Act]) and the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program (Title XVI of the Act) are the two largest federal programs providing cash benefits and medical assistance to blind and disabled persons. Title II is an insurance program providing payments for disability to persons based on their previous employment covered under the Social Security program. Title XVI is a means-tested income assistance program for the aged, blind, and disabled regardless of their prior participation in the labor force. It provides financial assistance to individuals who have limited income and resources regardless of their previous work history. The definition of disability and the decision process for assessing disability are the same for both programs.

The Social Security Act defines disability (for adults) as “… inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months…” (Section 223 [d][1]). Amendments to the Act in 1967 further specified that an individual's physical and mental impairment(s) must be “… of such severity that he is not only unable to do his previous work but cannot, considering his age, education, and work experience, engage in any other kind of substantial gainful work which exists in the national economy, regardless of whether such work exists in the immediate area in which he lives, or whether a specific job vacancy exists for him, or whether he would be hired if he applied for work” (Section 223 and 1614 of the Act).

Although the existence of a medically determinable impairment is a necessary condition, it is not a sufficient condition for receipt of benefits. The definition makes clear that this program deals with work disability. The applicant is considered to be “disabled” (as defined by the Act) not just because of the existence of a medical impairment, but because the impairment precludes gainful work (Hu, et al., 1997). However, determination of disability is a complex process, inescapably involving some interpretive judgments about capacity for work (GAO, 1994). Therefore, it is impossible to know precisely the extent of imperfection in the determination of disability, as evidenced by the lack of agreement observed in an examination of rater reliability as measured by the variations within and between states in the allowance rates by examiners (Gallicchio and Bye, 1980).

Over the years statutory amendments and judicial construction of eligibility criteria have extended the scope of the program. Many other factors have also contributed to the growth of the programs: incentives to apply for benefits affected by changes in the structure of alternative public and private income support programs for persons with disabilities, economic conditions, structural shifts in the labor market, and changes in the composition and characteristics of working age population (Lahiri, et al., 1995; Hu, et al., 1997). At the same time SSA has faced reductions in its administrative resources. As a result SSA has been faced with large workload increases in the disability programs and consequent backlogs in claims and appeals. These increases, however, have not been matched by increases in personnel. A study conducted by SSA (1993) of the disability claim and appeal processes found that the processing time for a claim from the initial inquiry through receiving an initial claims decision notice can take up to 155 days, and through receipt of hearing decision notice, can take as long as 550 days. However, the actual time during this period that employees devote to working directly on a claim was found to be 13 hours up to the initial decision notice and 32 hours through receipt of hearing decision notice. Delays in the receipt of required medical evidence at each level and consultations, the movement of paper, and the wait at each workstation because of missing information as the case is developed, account for a considerable portion of the claims processing time (SSA, 1994a). Increases in litigation combined with major reductions in staff resources have also contributed to the claims backlog.

Errors in making denial decisions by the state disability determination service (DDS) adjudicators, backlogs in appeals, and inconsistencies in decisions reached by the DDS adjudicators and the administrative law judges (ALJs) are also a matter of concern (DHHS, 1982; GAO, 1995, 1997b). The decision-making standards and procedures used by the ALJs are not always the same as those followed by the DDS adjudicators. The inconsistent decisions result mostly from differences in the assessment of residual functional capacity. The number of decisions being appealed for reconsideration and then approved at the higher level has increased. Over time the process has become lengthy, fragmented, confusing, and burdened by complex policies applied at different adjudicatory levels. It is hardly surprising that many have complained that the Social Security claims process takes too long, is confusing, complicated, and fragmented, resulting in inconsistent decisions often based on subjective criteria (GAO, 1995, 1997a; SSA, 1994a).

In the early 1990s, the National Performance Review identified improvement of the Social Security Administration's (SSA) disability process as one of the key service initiatives for the federal government. SSA realized that significant improvements could not be achieved without fundamentally restructuring the entire claims process. In view of these numerous concerns and the agency's recognition of the need to improve the quality of the service in the disability claims process, SSA decided to develop an ambitious long-term strategy for reengineering “… the disability determination process that would be simpler than the existing one, deliver significantly improved service to the public, remain neutral with respect to program dollar outlays, and will be more efficient to administer” (SSA, 1994a, p. 46).

As outlined by SSA (1994a), the basic goals of the reengineered claims process are that it should be:

-

user-friendly to the claimant and those who assist them;

-

prompt, that is, decisions are made quickly;

-

accurate, that is, the correct decision is made the first time;

-

efficient; and

-

conducted in a work environment satisfying for employees.

DISABILITY DETERMINATION-STRUCTURE AND PROCESS

Disability Claims Process

The Social Security disability claims process1 starts at the state disability determination service where most disability decisions are made for SSA at the initial and reconsideration levels. Briefly, the claims process proceeds through a series of four stages or levels: (1) applications for benefits and preliminary screening are made at the SSA district offices; (2) disability determinations are made in state DDS agencies using federal regulations and SSA guidelines and procedures; (3) claimants whose applications are denied can have their claims reconsidered at the DDS level; and (4) if benefits are denied during the reconsideration, the claimant may request a hearing before an ALJ at the SSA. Further appeals options include a request for review of the denial decision by SSA's Appeals Council, and then review in the federal courts.

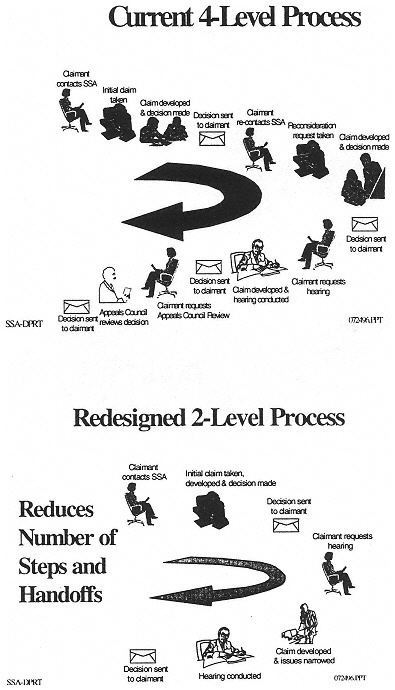

SSA envisions that the reengineered claims process will make efficient use of technology, eliminate fragmentation and duplication, and promote flexible use of resources. Claimants will be given understandable program information and a range of choices for filing a claim and interacting with SSA. They will deal with one contact point and will have the right to a personal interview at each level of the process. Also, the number of levels in the new claims process prior to Appeals Council review will be consolidated from four to two, and the issues for which appeals will be allowed will be more focused. Finally, if the claim is approved, the initiation of payment will be streamlined. The current and the proposed claims processes are illustrated in Figure 2-1.

Successful reengineering depends on a number of key initiatives of a new claims process. SSA's original plan depended on a large number of initiatives which together were intended to make the reengineered claims process function efficiently. Since then the agency has reassessed many of the reengineering initiatives and developed a revised plan that focuses on eight major areas for priority attention. Four of these initiatives are testing efforts (single decisionmaker, adjudication officer, full process model, and disability claims manager), and four are developmental activities that SSA calls “critical enablers” (systems support, process unification, simplified decision process, and quality assurance) (SSA, 1998b). Thus the redesign of the disability decision process is one, but only one, of the process changes proposed by SSA to achieve reengineering of the disability claims process.

Evaluation of Eligibility for Disability Benefits

The disability decision process has been referred to as a gatekeeping function for the SSDI and SSI programs (Lahiri, et al., 1995; Hu, et al., 1997). The statute defines disability but does not define the standards for evaluating disability claims. The process for evaluating disability claims is specified in SSA's implementing regulations (20 Code of Federal Regulation, parts 404 and 416, subparts P and I) and in written guidelines that describe a series of sequential decision points and criteria for determining whether or not a claimant meets the statutory definition of disability.

The purpose of developing the sequential decision process was to provide an operationally efficient definition of disability with a degree of objectivity that can be replicated with uniformity throughout the country. The objective was to adjudicate claims as consistently, expeditiously, and cost effectively as possible. As stated earlier in the chapter, however, over the years this decision process has become complex, inconsistent, and difficult for the claimant to understand.

The Current Decision Process for Initial Claims.

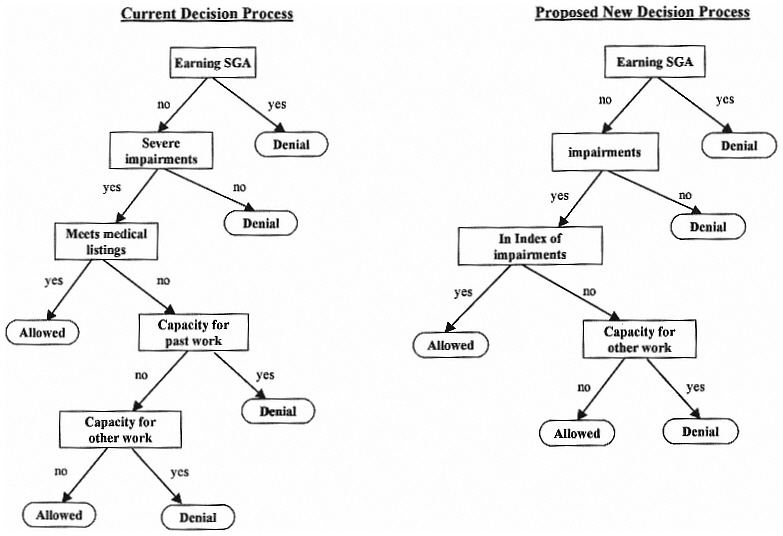

The disability decision process for initial claims involves five sequential decision steps (SSA, 1994a). SSA's field offices and the state disability determination service make the initial decisions on applications for disability benefits.

-

In the first step, or point of decision, the SSA field office reviews the application and screens out claimants who are engaged in substantial gainful activity (SGA).

-

If the claimant is not engaged in SGA, step two determines if the claimant has a medically determinable severe physical or mental impairment. The regulations define severe impairment as one that significantly limits a person's physical or mental ability to do basic work activities.

-

During the third decision step, the documented medical evidence is assessed against the medical criteria to determine if the impairment meets or equals the degree of severity specified in SSA's “listings of impairments.” A claimant whose impairment(s) meets or equals those found in the listings is allowed benefits at this stage on the basis of the medical criteria.

-

In the fourth decision step, claimants who have impairments that are severe, but not severe enough to meet or equal those in the listings, are evaluated to determine if the person has residual functional capacity (RFC) to perform past relevant work. Assessment of the RFC requires consideration of both exertional and nonexertional impairments. If a claimant is determined to be capable of performing past relevant work, the claim is denied.

-

The fifth and final decision step considers the claimant's RFC in conjunction with his or her age, education, training, and work experience, commonly referred to as vocational factors, to determine if the person can perform other work that exists in significant numbers in the national economy.

Proposed Redesigned Decision Process

As stated above, the redesign of the disability decision process is only one of the many process changes proposed in the reengineered disability claims process. SSA has stated that such a redesigned decision process should:

-

be simple to administer;

-

facilitate consistent application of rules at each decision level;

-

provide accurate and timely decisions; and

-

be perceived by the public as straightforward, understandable, and fair.

SSA aims “… to focus the new decision-making approach on the functional consequences of an individual's medically determinable impairment(s)” (SSA, 1994a, p. 21). According to SSA, in the proposed redesigned disability decision process the presence of a medically determinable impairment will remain a necessary requirement for eligibility, as required by the current law. SSA, however, proposes to focus directly on developing new ways to assess the applicant's functional ability or inability to work as a consequence of the medical impairment and to rely on these standardized functional measures to reach decisions. Medical and technological advances and societal perceptions about work capacity of a person with disabilities appear to support a shift in emphasis from the current focus on disease conditions and medical impairments to that of functional inability. For example, people with disabilities are able to function with personal assistants and assistive devices.

The redesigned disability decision process, as conceived by SSA, will involve four sequential steps for deciding if a claimant meets the definition of disability as defined in the Act.

-

The first step is the same as in the current process. It involves screening out applicants who are engaged in substantial gainful activity.

-

If the claimant is not engaged in SGA, the second step evaluates if the applicant has a documented medically determinable physical or mental impairment. Under the proposed revision, however, a threshold “severity” requirement will no longer be needed.

-

The third step assesses if the person's impairment is included in an index of disabling impairments (yet to be developed). The index will replace the current listings of impairments. It will contain a short list of impairments of such severity that, when documented, they can be presumed to result in loss of the person's functional ability to perform substantial gainful activity without the need to further measure the individual's functional capacity and without reference to the person's age, education, and previous work experience.

-

If the claimant's medical impairment(s) is not in the index, the fourth and final decision step will evaluate if the individual has the functional ability to perform any substantial gainful activity. These individualized assessments of functional ability will also take into consideration the effects of the vocational factors in determining the demands of the individual's previous work. Functional assessment instruments will be designed to measure an individual's abilities to perform a baseline of occupational demands that include the primary dimensions

-

of work and that exist in significant numbers in the national economy (SSA, 1994a).

The final decision step of the proposed decision process subsumes both steps four and five of the current decision process. According to SSA, this step reflects the most significant change from the current decision process. SSA has assumed that under this proposed decision process, the majority of claimants will be evaluated at this point using a standardized approach to measuring functional ability to perform work. Conceptually, standardized measures of functional ability that are universally acceptable would facilitate consistent decisions regardless of the professional training of the decisionmakers in the decision process.

The sequential disability decision process as it exists today and the proposed new process are illustrated in Figure 2-2.

COMMISSIONER'S CONCLUSIONS

In 1994 the Commissioner of SSA accepted the proposal for a plan to reengineer the disability claims process with the understanding that redesign of the decision process would require extensive research and testing to determine whether it could be implemented. She stated that “Because those aspects of decisional methodology [sic] that deal with functional assessment, baseline of work, and the evaluation of age require much study and deliberation with experts and consumers, we are making no conclusions about their ultimate place in the disability process.” (SSA, 1994a, p. i).

The proposed reengineering of the claims process is in various stages of implementation. In response to the commissioner's directive, however, SSA has not yet implemented the disability decision process element of their total reengineering proposal. The agency is now engaged in a multiyear research effort to develop and test the feasibility, validity, reliability, and practicality of the redesigned disability determination process prior to any decision on its national implementation. SSA has developed what it refers to as the “research plan” for the disability decision process and a timeline for its completion (SSA, 1996, 1997b).

The agency requested the National Academy of Sciences to conduct an independent and objective review of, and make recommendations on, its current and proposed research that relates to the proposed redesigned disability decision process, including all aspects of the complex, multiyear Disability Evaluation Study. (See the Appendix for the study mandate.)

This second interim report is limited to a preliminary review of SSA's research plan for developing a new disability decision process and the timeline for its completion.