1

Introduction

Background

In May 1998 the National Institutes of Health asked the National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council to assemble a group of experts to examine the scientific literature relevant to work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the lower back, neck, and upper extremities. A steering committee was convened to design a workshop, to identify leading researchers on the topic to participate, and to prepare a report based on the workshop discussions and their own expertise. In addition, the steering committee was asked to address, to the extent possible, a set of seven questions posed by Congressman Robert Livingston on the topic of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. The steering committee includes experts in orthopedic surgery, occupational medicine, epidemiology, ergonomics, human factors, statistics, and risk analysis.

This document is based on the evidence presented and discussed at the two-day Workshop on Work-Related Musculoskeletal Injuries: Examining the Research Base, which was held on August 21 and 22, 1998, and on follow-up deliberations of the steering committee, reflecting its own expertise. We note the limitations of the project, both in terms of time constraints and sources of evidence.

Although reports on the number of work-related musculoskeletal disorders vary from one data system to another, it is clear that a sizable number of individuals report disorders and lost time from work as a result of them.1 For example, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (1995) has reported that in one year there were 705,800 cases of days away from work that resulted from overexertion or pain from repetitive motion. Estimated costs associated with lost days and compensation claims related to musculoskeletal disorders range from $13 to $20 billion annually (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 1996; AFL-CIO, 1997). The multiplicity of factors that may affect reported cases—including work procedures, equipment, and environment; organizational factors; physical and psychological factors of the individual; and social factors—has led to much debate about their source, nature, and severity. In light of the ongoing debate, an extensive internal review of the epidemiological research was recently done by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (Bernard, 1997). That study is part of the work that was considered by the steering committee.

The charge to the steering committee, reflected in the focus of the workshop, was to examine the current state of the scientific research base relevant to the problem of work-related

musculoskeletal disorders, including factors that can contribute to such disorders, and strategies for intervention to ameliorate or prevent them. Approximately 110 leading scientists were invited by the steering committee to participate in the workshop, and 66 were able to attend. The attendees represented the fields of orthopedic surgery, occupational medicine, public health, epidemiology, risk analysis and decision making, ergonomics, and human factors (see Appendix A). Several attendees presented prepared papers; many others presented oral and written responses to the papers or comments on the field of inquiry. Two criteria guided the selection of invitees: that they are involved in active research in the area and that the group, overall, represent a wide range of scientific disciplines and perspectives on the topic.

In designing the workshop, the steering committee considered several approaches to framing the topics. After careful consideration, we chose not to have the presentations focus on specific parts of the body and associated musculoskeletal disorders. Rather, we organized our examination of the evidence—and the workshop discussions (see agenda, Appendix B)—to elucidate the following sets of relationships between factors that potentially contribute to musculoskeletal disorders: (1) biological responses of tissues (muscles, tendons, and nerves) to biomechanical stressors; (2) biomechanics of work stressors, considering both work and individual factors, as well as internal loads; (3) epidemiological perspectives on the contributions of physical factors; (4) non-biomechanical (e.g., psychological, organizational, social) factors; and (5) interventions to prevent or mitigate musculoskeletal disorders, considering the range of potentially influential factors. Our belief was that this approach would provide a framework for reviewing the science base for each set of relationships, as well as the wider interactions among the sets. This approach allowed us to take advantage of both basic and applied science and a variety of methodologies, ranging from tightly controlled laboratory studies to field observations. As a result, we considered sources of evidence that extend well beyond those provided by the epidemiological literature on which the public discussion has focused.

Discussions in each of five of the topic areas (all but topic 4) revolved around a paper commissioned for the workshop and comments of invited discussants; a panel format was used to address the epidemiology of physical factors (topic 4), given the availability of recent reviews of literature on this topic.

The next section presents a conceptual framework integrating the factors thought to be related to the occurrence of musculoskeletal disorders. We used this framework to select and organize topics covered in the workshop.

Framework of Contributors to Musculoskeletal Disorders

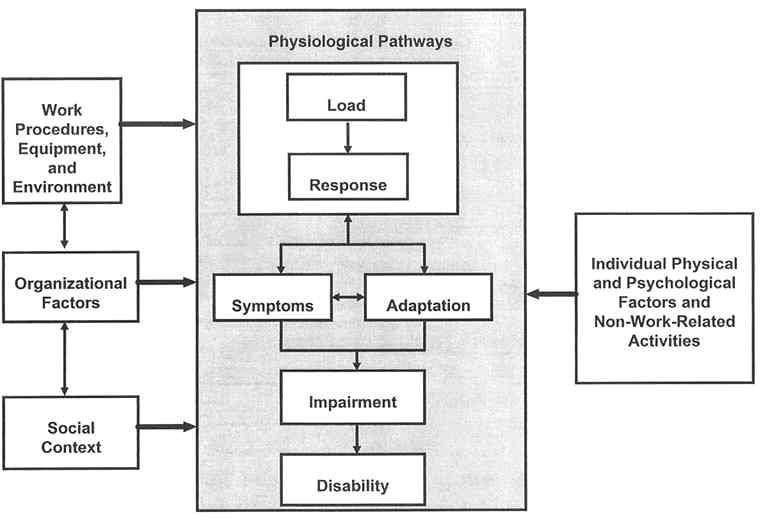

Figure 1 outlines a broad conceptual framework, indicating the roles that various work and other factors may play in the development of musculoskeletal disorders. This framework serves as a useful heuristic to examine the diverse literatures associated with musculoskeletal disorders, reflecting the role that various factors—work procedures, equipment, and environment; organizational factors; physical and psychological factors of individuals; non-work-related activities; organizational factors; and social factors—can play in their development. Its overall structure suggests the physiological pathways by which musculoskeletal disorders can occur or, conversely, can be avoided.

The central physiological pathways appear within the shaded area of the figure. It shows, first, the biomechanical relationship between load and the biological response of tissue. Imposed loads of various magnitudes can change the form of tissues throughout the day due to changes in fatigue, work pattern or style, coactivation of muscle structures, etc. Loads within a tissue can produce several forms of response. If the load exceeds a mechanical tolerance or the ability of the structure to withstand the load, tissue damage will occur. For example, damage to a vertebral end plate will occur if the load borne by the spine is large enough. Other forms of response may entail such reactions as inflammation of the tissue, edema, and biochemical responses.

Biomechanical studies can elucidate some of these relationships. Biomechanical loading can produce both symptomatic and asymptomatic reactions. Feedback mechanisms can influence the biomechanical loading and response relationship. For example, the symptom of pain might cause an individual to recruit his or her muscles in a different manner, thereby changing the associated loading pattern. Adaptation to a load might lead individuals to expose themselves to greater loads, which they might or might not be able to bear. Repetitive loading of a tissue might strengthen the tissue or weaken it, depending on circumstances. The symptom and adaptation portions of the model can interact with each other as well. For example, symptoms, such as swelling, can lead to tissue adaptations, such as increased lubricant production in a joint. These relationships can be described in mathematical models that distinguish external load (e.g., work exposure) from internal (dose) load and illustrate cascading events, whereby responses to loads can themselves serve as stimuli that increase or decrease the capacity for subsequent responses.

The responses, symptoms, and adaptations can lead to a functional impairment. In the workplace, this might be reported as a work-related musculoskeletal disorder. If severe enough, the impairment would be considered a disability, and lost or restricted workdays would result.

To the left of the shaded area in Figure 1, the framework shows environmental factors that might affect the development of musculoskeletal disorders, including work procedures, equipment, and environment; organizational factors; and social context. For example, physical work factors (reaching, close vision work, lifting heavy loads) affect the loading that is experienced by a worker's tissues and structures. Organizational factors can also influence the central mechanism. Although little studied, hypothetical pathways also exist between organizational influences and the biomechanical load-response relationship, as well as the development of symptoms. For example, time pressures to complete a task might induce carelessness in handling a particular load, with consequent tissue damage. The organizational culture can also create an incentive or a disincentive to report a musculoskeletal disorder or to claim that the impairment should be considered a disability. Social context factors, such as a lack of means to deal with psychological stress (e.g., no spousal support), might also influence what a worker reports or even the worker's physiological responses.

To the right in Figure 1, the framework shows the influence of individual physical and psychological factors, as well as non-work-related activities, that might affect the development of musculoskeletal disorders. For example, psychological factors can affect a person's identification of a musculoskeletal disorder or willingness to report it or to claim that the impairment is a disability. Physical factors might involve reduced tissue tolerance due to age or gender or disease states, such as arthritis, which can affect people's biochemical response to tissue loading.

This framework can accommodate the diverse literatures regarding musculoskeletal disorders by characterizing the pathways that each study addresses. For example, an epidemiological investigation might explore the pathways between the physical work environment and the reporting of impairments or the pathway between organizational factors and the reporting of symptoms. An ergonomic study might explore the pathways between work procedures and equipment and the biomechanical loads imposed on a tissue. This framework also focuses attention on the interactions among factors. For example, the combination of a particular set of work procedures and organizational factors might produce an increase in disorders that neither would alone produce.

Looking at the evidence as a whole provides a sounder basis for understanding the overall dimensions of the problem of work-related musculoskeletal disorders than restricting an examination to any one factor or kind of evidence. It also places individual studies in context, by showing the factors and pathways that they do and do not address.