Irvine H. Page's group to discuss the formation of a National Academy of Medicine met for the first time on January 17, 1967, at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Although Page never realized his ambition to create such on academy, this group supplied the impetus that eventually led to the founding of the institute of Medicine. Top, left to right: Fay H. Lefevre, M.D.; J. Englebert Dunphy, M.D.; Carleton B. Chapman, M.D.; Francis D. Moore, M.D.; William B. Bean, M.D.; John B. Hickam, M.D.; E. Cowles Andrus, M.D.; Robert A. Aldrich, M.D.; Ivan L. Bennett, Jr., M.D.; and Stuart M. Sessoms, M.D.; Bottom, left to right: James A. Shannon, M.D.; Frederick C. Robbins, M.D. (who would later become the institute's fourth president, in 1980); Irving S. Wright, M.D.; Irvine H. Page, M.D.; Douglas D. Bond, M.D.; and Robert H. Williams. Photograph courtesy of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Fredrick Seiz, Ph.D., a distinguished physicist, created the Board on Medicine in 1967 during his tenure as president of the National Academy of Sciences (1962-1969). Photograph by Harris and Ewing, Washington D.C., courtesy of the National Academy of Sciences.

Walsh McDermott, M.D., a professor of medicine and public health at Cornell Medical School, chaired the Board on Medicine and played a leading role in the creation of Institute of Medicine. Photograph courtesy of The New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center Archieves.

Irving M. London, M.D., who was chairman of the Department of Medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in 1967, was a key ally of Walsh McDermott on the Board on Medicine. Photograph courtesy of Irving London.

Julius H. Comroe, Jr., M.D., director of the Cardiovascular Research Institute of the San Francisco Medical Center, tended to side with Irvine Page in the dedated over the creation of the Institute of Medicine. Photograph courtesy of the University of California at San Francisco.

James A. Shannon M.D., director of the National Istitutes of Health from 1955 to 1968, believed that the government's role in medical research. Photograph by Ralph Fernandez. courtesy of the History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine.

Robert J. Glaser, M.D., who was dean of Stanford's School of Medicine's heart transplant statement and chaired the Institute's Initial Membership Committee. He also served as acting president of the Institute until John Hogness took office in the spring of 1971. Photograph courtesy of Robert Glaser.

Irvine H. Page, M.D., who was head of the Research Division at the Cleveland Clinic from 1945 to 1967 and a leading expert on hypertension and heart disease, was a strong advocate for the creation of a National Academy of Medicine. He and Walsh McDermott engaged in spirited debated within the Board on Medicine. Photograph courtesy of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Philip Handler, Ph.D., a well-known biomedical researcher at Duke University who was president of the National Academy of Sciences from 1969 to 1981, played a key role in the creation of the Institute of Medicine and in its early development. His constant goal was to maintain the integrity of the Academy. Photograph courtesy of the National Academy of Sciences Archives.

Presidents of the Institute of Medicine

John R. Hogness, M.D. (1970–1974), was the Institute of Medicine's first president. He started the IOM Council and initiated many of the routines that governed the Institute's development.

Donald S. Fredrickson, M.D. ( 1974–1975), a distinguished biomedical researcher, stayed only a short time at the Institute before leaving to become director of the National Institutes of Health.

David A. Hamburg, M.D. (1975–1980), helped to bring the institute to national prominence. He established the divisions that still underlie the basic organizational scheme of IOM.

Frederick C. Robbins, M.D. (1980–1985), a Nobel laureate, brought his knowledge of medical research to the Institute, helping the organization to overcome the challenge posed by the Sproull report.

Samuel O. Thier, M.D. (1985–1991), energized the Institute and led a successful fund-raising effort. As a result of his work, IOM reached parity with the other components of the Academy complex.

Kenneth I. Shine, M.D. (1992–present), ushered the Institute into its second quarter century. Now in his second term, he is IOM's longest-serving president.

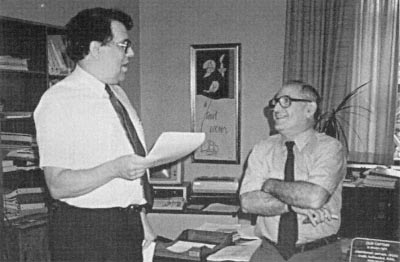

Karl Yordy (left), a durable and valuable member of the Institute's staff, served the IOM from the era of John Hogness into the era of Ken Shine, both as executive officer after Roger Bulger and as director of the Division of Health Care Services. Charles Miller (right) succeeded Yordy as executive officer, serving from 1983 to 1988—years that encompassed threats associated both with possible insolvency and the Sproull report, and then increasing financial security and expansion of the Institute's program. Photograph courtesy of Jana Surdi.

The Institute's first executive officer, Roger J. Bulger, M.D., was a close associate of John Hogness. He guided the daily operations of the Institute in its early years and went on to a distinguished career in medical administration, most recently as president of the Association of Academic Health Centers. Photograph courtesy of the Association of Academic Health Centers.

Enriqueta C. Bond Ph. D. Samuel Their relied heavily on Queta Bond to manage the day-to-day affairs of the Institute. She served in different capacities under a number of IOM presidents before assuming the presidency of the Burroughs Wellcome Fund in 1994. Photograph courtesy of the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Karen Hein, M.D., a former Robert Wood Johnson Health Policy Fellow, served as the Institute's executive officer from 1995 until 1998 before leaving to become president of the William T. Grant Foundation. Photograph courtesy of Karan Hein.

Susanne Stoiber, M.S., M.P.A., was named IOM executive officer in 1998. She came to the Institute from the Department of Health and Human Services, where she was deputy assistant secretary for planning and evaluation. In a previous stint at the Academy, she directed the Division of Social and Economic Studies. Photograph courtesy of Susanne Stoiber.

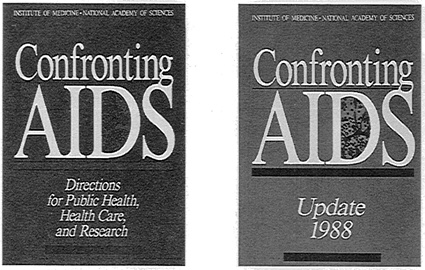

An M.D.-Ph.D. with a background in cardiovascular surgery and long a major figure at the Institute, Theodore Cooper chaired the study that produced Confronting AIDS: Update 1988. Photograph courtesy of Pharmacia & Upjohn.

Robert A. Derzon, M.B.A., a distingushed hospital administrator, followed his service as the first head of the Health Care Financing Administration with a period as a scholar in residence at the Institute. He was an IOM Council member during Fred Robbin's tenure and helped recruit Samuel Thier. Photograph courtesy of Robert Derzon.

Robert M. Ball, M.A., head of the Social Security Administration from 1962 to 1973, became a scholar in residence at the Institute and served as a confidante of IOM presidents from Hogness through Robbins.

Watergate —a national preoccupation from 1972 to 1974, and a word that became synonymous with political scandal—originated with a burglary that took place on the night June 17, 1972, in this fashionable Washington, D.C., office complex. In 1974, the institute moved into the 6th-floor offices that the Democratic National Committee had recently vacated. Its offives attracted tourists and others interested in the "stuff of history." Photograph courtesy of Elena Nightingale.

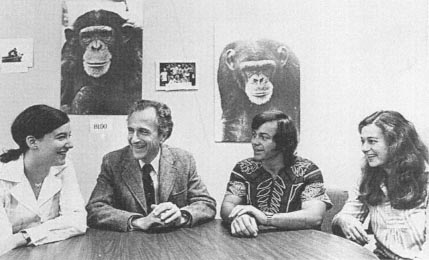

If one of the more unusual circumstances to affect the Institute, before David Hamburg could accept the presidency of IOM in 1975, he needed to negotiate the release in Zaire. He is shown here back in Stanford with (from left) Carrie Hunter, Steven Smith, and Emilie Bergman after their release in the fall of 1975. Photograph courtesy of David Hamburg.

Joseph A. Califano, Jr., LL.B., President Jimmy Carter's Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, worked closely with the Institute in the Hamburg era, and ultimately was elected an IOM member and a member of the IOM Council. Photograph courtesy of the History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine.

Robert Sproull, Ph.D., a well-knwon physicist and president of the University of Rochester, chaired a committee whose 1984 report advocated the transformation of the Institute into an academy of medicine and led to some particularly painful moments for the young organization. Photograph courtesy of the University of Rochester.

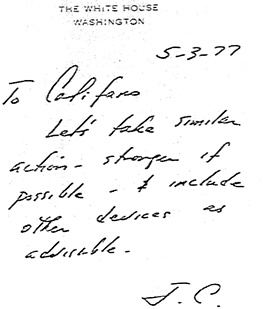

In early May 1977, a Washington Post article on the recently released IOM study Computed Tomographic Scanning caught President Jimmy Carter's eye. the study urged that hospital and physicians should not overuse the new technology and that local health planners should approve the installation of new scanners, as well as ensure that they operated efficiently. Carter wanted Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Califano to read the article as well.

Confronting AIDS (1986) commanded public attention and urged the nation to do more to combat this deadly epidemic. A follow-up report, Confronting AIDS, UPdate 1988, was used by President George Bush to help formulate government policy toward AIDS.

Preventing Low Birthweight attracted a great deal of attention in part because of the dramatic way in which it was released in the spring of 1985 during hearing conducted by Representative Henry Waxman(D-Calif.).

In recent years, the Institute has produced reports that grab a reader's attention visually as well as engaging them with substantive issues, as the covers of these reports shows—Growing Up Tobacco Free: Preventing Necotine Addiction in Children and Youths (1994, top left), Eat for Life: The Food and Nutrition Board's Guide to Reducing Your Risk of Chronic Disease (1992, top right), and In Her Lifetime: Female Morbidity and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa (1996, below), Such covers are strikingly different from the more ultilitarian documents that the Institute produced during its early years.

Current National Academy of Sciences President Bruce Alberts, Ph.D. (left), joins past NAS President Fredrick Seitz, Ph.D. (right), at the April 1995 dedication of a partrait of Frank Press, Ph.D. Press, a noted physical scientist from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, had been president Carter's science advisor prior to taking over as NAS president in 1981. Albert, a well-known biochemist and molecular biologist from the University of California at San Francisco, succeeded Frank Press in 1993. Photograph courtesy of the National Academy of Sciences.