2

Overview of the Older Americans Act Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program

Our nation has been conducting investigations, passing new laws and issuing new regulations relative to nursing homes at a rapid rate during the past few years. All of this activity will be of little avail unless our communities are organized in such a manner that new laws and new regulations are utilized to deal with the individual complaints of older persons who are living in nursing homes. The individual in the nursing home is powerless. If the laws and regulations are not being applied to her or to him, they might just as well not have been passed or issued.

—Arthur S.Flemming, former Commissioner on Aging, 1975

Concerns with the quality of nursing facilities, the care provided in them, and the government’s ability to enforce regulations in these facilities led to the creation of the long-term care (LTC) ombudsman program in the early 1970s. In contrast to regulators, whose role is to apply laws and regulations, the mission of ombudsmen was to help identify and resolve problems on behalf of residents, in order to improve their overall well-being. This chapter provides an overview of the program: how it evolved, its current status, and functions performed by its staff—the ombudsmen. It draws upon much of the work undertaken by the committee, including site visits, commissioned papers, testimony presented at the symposium, canvasses of key stakeholders, and a thorough literature review of secondary materials.

EVOLUTION OF THE LONG-TERM CARE OMBUDSMAN PROGRAM

Ombudsman Theory and Practice

Originally conceived by the Swedish parliament in 1809, the ombudsman was a government official with high personal prestige and independence who would listen to the complaints of individual citizens about the government and try to resolve them in an impartial manner. More broadly conceptualized, an ombudsman is a “public watchdog” or “citizen defender” who intercedes between a citizen and some form of authority. In addition to offering protection against the impersonality of bureaucracy, he or she also seeks to increase government’s responsiveness and accountability, provides a complaint processing system, and suggests ways to reorganize services in response to a pattern of complaints (Ziegenfuss, 1985).

In his analysis of social criticism, political philosopher Michael Walzer (1988) suggests that the role of the critic is to distinguish between and call attention to what we really are and what we most want to be. The critic is an insider, rooted in his or her society, who has obtained some critical distance. The ombudsman, as critic but also as activist, derives his or her philosophical authority from fundamental American beliefs in human rights and dignity. No matter their political persuasion, members of our society seem to recognize “the respect for life, integrity, and well-being, even the flourishing of others” as profoundly important moral concerns (Taylor, 1989).

In 1971, when the LTC ombudsman program was first proposed, the idea of the ombudsman was gaining increasing popularity in American government. In that same year, the Department of Commerce established the first ombudsman in a federal agency, and since that time a number of federal agencies, including the Internal Revenue Service, the Social Security Administration, and the Environmental Protection Agency, have followed suit. Additionally, many states, counties, and other jurisdictions have implemented ombudsman programs. Ombudsmen can also be found in unions, newspaper offices, colleges, universities, schools, and corporations. Many private hospitals and the Department of Veterans Affairs also employ patient representatives, who act in a similar advocate role on behalf of acute-care patients.

Although the classic characterization of the “ombudsman” stresses neutrality and mediation, the role of the LTC ombudsman is considered a hybrid, since it was designed for active advocacy and representation of residents’ interests over those of other parties involved. Additionally, classic ombudsman models involve intervention between the government and individual citizens. In the case of the LTC ombudsman program, however, intervention usually also includes a private third party—the nursing facility or board and care (B&C) home. The extension of this role is legitimized by the government’s substantial involvement, both as

a regulator and reimburser, with these industries. In this way, as an engaged critic of both government and private industry, the LTC ombudsman plays a unique role.

History of the Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program

Responding to growing concerns about the quality of nursing facilities, the care provided in them, and the government’s ability to regulate and enforce laws regarding these facilities, President Nixon proposed an eight-point initiative in 1971 to improve conditions in the nation’s nursing facilities. One of the eight points called for using “state investigative ombudsman units” to improve quality of care by focusing exclusively on the resident, thereby compensating for the limitations of regulations and other quality assurance strategies (Butler, 1975). In 1972, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW), Health Services and Mental Health Administration, awarded five contracts for states to implement nursing home ombudsman demonstration programs. The demonstrations took place in Idaho, Michigan, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Wisconsin.

During a DHEW reorganization in 1973, the Administration on Aging (AoA) received administrative responsibility for the demonstration programs. Assignment of the programs to AoA was consistent with AoA’s statutory responsibilities for advocacy and coordination on behalf of the elderly at the federal level. Additionally, the move placed the programs within the infrastructure of the “aging network” of state and area agencies on aging. This network of agencies is authorized, through the Older Americans Act (OAA), to foster the development and implementation of a vast array of supportive services for individuals 60 years of age or older.

The structure of the aging network consists of the AoA and 10 regional offices at the federal level; state units on aging (SUAs) in all states and territories; 670 area agencies on aging (AAAs); and thousands of direct service providers. When it first was formed in the late 1960s, few state and area agencies actually provided services directly. Today, however, SUAs and AAAs are deeply involved in the provision of community-based LTC (AoA, 1994b). (For a more complete description of the aging network, see Appendix A.)

In May 1975, then Commissioner on Aging Arthur S.Flemming invited all SUAs to submit proposals for grants “to enable the State Agencies to develop the capabilities of the Area Agencies on Aging to promote, coordinate, monitor and assess nursing facility ombudsman activities within their service areas.” The grants sought primarily to inaugurate, in as many areas as possible, community action programs dedicated to identifying and dealing with the complaints of older persons or their relatives regarding the operation of nursing facilities. All states except Nebraska and Oklahoma received grants the first year and hired nursing

facility “ombudsman developmental specialists.” Most of these specialists worked out of the SUA.

This strategy of establishing statewide coverage through the use of local programs, rather than through a single, central state program, influenced the evolution of the program significantly. The demonstration programs had indicated that a centrally located program with no local programs would encounter great difficulty in responding to the volume and variety of needs of individuals throughout the state. Therefore, the paid ombudsman developmental specialists were used to develop and support local programs, rather than personally provide complaint resolution. Given the limited funding available, the developmental approach was seen as the only means by which the goal of statewide ombudsman coverage could be attained (LRSE, 1977).

Existing citizen advocacy organizations and volunteers, as well as government agencies and employees, acted as sponsors of local programs, and these entities constituted a second, albeit more subtle, influence on how the program evolved. The use of these private entities underscored the notion that, in the nursing facility ombudsman program, the ombudsman was not meant to act as a neutral government agent. Many of these advocacy organizations had been founded in the era of the civil rights and women’s rights movements, and they naturally developed strong pro-resident advocacy missions. Many volunteers joined the program motivated by poor treatment of friends and relatives in nursing facilities (Holder and Frank, 1984). Although some nursing facility and B&C home providers believe that the original, and only legitimate, mission for LTC ombudsmen was to follow the classic, neutral, ombudsman model, in fact, the ombudsman program has always been designed to hold the residents’ interests as paramount. This misconception about the role ombudsmen should play, coupled with the great variation of models used by programs and individual ombudsmen, has caused many persistent misunderstandings among providers (Lusky et al., 1994).

The 1978 amendments to the OAA provided the ombudsman program with federal enabling legislation by requiring each state to establish an ombudsman program. SUAs were allowed to operate programs either directly or through subcontracts with public or private nonprofit agencies. The federal mandate instructed ombudsmen programs to investigate complaints; train and supervise volunteers; monitor the development of federal, state, and local laws, regulations, and policies; and provide public agencies with information about problems faced by LTC residents. The legislation and limited oversight by AoA, however, afforded individual states great flexibility in the actual operation of the program. As a result, state programs took on diverse tasks and emphases.

The charge of the ombudsman program grew considerably in 1981 when Congress added coverage of B&C facilities to the program’s mandated functions. The program’s name changed from “Nursing Home Ombudsman” to “Long-Term Care Ombudsman” to reflect more accurately its new responsibilities. Within

these B&C facilities, the ombudsmen’s charge is the same as their charge in nursing facilities. They are to investigate and resolve complaints, monitor regulations and policies affecting facilities, and provide information to public officials concerning residents in facilities. However, no additional federal funding accompanied this expansion. (This topic is further discussed in Chapter 3.)

In 1987, two major legislative changes greatly strengthened ombudsmen’s ability to reach and serve residents. The Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987 (Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987) mandated that nursing facility residents have “direct and immediate access to ombudspersons when protection and advocacy services become necessary.” Simultaneously, the 1987 reauthorization of the OAA charged states to guarantee ombudsmen access to facilities and patient records and provided other important legal protections. State ombudsmen were also given the official authority to designate local programs to carry out ombudsman functions. Duly authorized employees and volunteers of these programs could then be considered “representatives” of the state ombudsman with all the ombudsman’s rights and privileges accorded to them. Finally, amendments to the Act required the SUA to ensure the program had adequate legal counsel.

The 1992 OAA amendments highlighted the role of local ombudsman programs and the state ombudsman’s leadership role while reemphasizing each LTC ombudsman’s role as an advocate and agent for systemwide change. As a result, the LTC ombudsman program was incorporated into a new Title VII for “Vulnerable Elder Rights Protection Activities” of the OAA. This title (commonly referred to as “Elder Rights”) is designed to strengthen programs that assist older people in receiving the rights and privileges to which they are entitled. In addition to the ombudsman program, three other programs were authorized under Title VII: programs for the prevention of elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation; elder rights and legal assistance development programs; and benefits outreach, counseling, and assistance programs. Although each program retains its own distinctive features, the legislation also emphasizes the value of the four programs working closely to coordinate efforts.

STATUS OF THE CURRENT PROGRAM

Today the LTC ombudsman program operates in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. No single model can accurately describe these multifaceted programs. Variability in organizational placement, program operation, funding, and utilization of human resources has given rise to at least 52 distinctive approaches to implementing the program. Nonetheless, many commonalities do exist between these various approaches. For example, most

programs are housed within the SUA and utilize volunteers. A more in-depth examination of the variations and commonalities of the programs follows.

Organizational Placement

The Office of the State LTC Ombudsman is most often housed within the SUA (Table 2.1); this is the case in 42 states. The SUAs in these states themselves vary in their organizational placement. Half (21) are independent, single-purpose agencies that report directly to the governor. The other half are part of larger “umbrella” agencies, in which several other agencies report to a head office that in turn reports to the governor; in 9 of these states, the umbrella agency includes the agency responsible for licensing or certifying LTC facilities. Of the 10 state ombudsman programs that are not housed in a SUA, 3 reside in independent state-run ombudsman agencies and 7 reside completely outside state government (5 in legal services agencies, 2 in nonprofit citizen advocacy agencies).

Seventeen states operate their ombudsman program from a centralized office (some have regional offices). Thirty-five states have developed distinct local programs (sometimes referred to as “substate” programs). In FY 1993, 467 such local programs were in operation within these 35 states (Table 2.1). A variety of local organizations, most frequently AAAs, sponsor these programs. Of these 35 states, 12 place local programs only within AAAs, 2 house their local programs solely within nonprofit citizen advocacy agencies, 1 uses only legal service agencies, and 1 relies on state regional service agencies. The remaining 19 states employ a variety of AAAs, nonprofit agencies, and legal service agencies to house local programs.

Operation

How the program actually operates in a given state can be described as centralized, decentralized, or a combination of the two (Table 2.1). In 17 states the program is centralized, and the state ombudsman directly employs and supervises all paid and volunteer staff. Twenty-seven programs are considered decentralized; the state ombudsman has established local programs, which employ and supervise paid staff and volunteers. The remaining 8 states use a combination of these two approaches: part of the state is served by local programs and the rest of the state is directly served by state ombudsman staff.

TABLE 2.1 Organizational Placement and Operation of the Long-Term Care Ombudsman Programs, by State

|

State |

State Ombudsman Placement |

Number of Local Programs |

Local Ombudsman Placement |

Operation of Statewide Program |

Special Aspects of Program |

|

Alabama |

independent SUA |

13 |

AAAs |

decentralized |

|

|

Alaska |

SUA in umbrella agency w/o L&C |

0 |

none |

centralized |

|

|

Arizona |

SUA in umbrella agency w/o L&C |

9 |

variety |

decentralized |

Local programs are located in councils of government and county government agencies. |

|

Arkansas |

SUA in umbrella agency w/L&C |

8 |

AAAs |

decentralized |

|

|

California |

SUA in umbrella agency w/L&C |

35 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Colorado |

legal agency |

16 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Connecticut |

SUA in umbrella agency w/o L&C |

0 |

none |

centralized |

Ombudsman program is operated directly by the SUA. State staff who serve as regional ombudsmen are housed in freestanding regional offices. |

|

Delaware |

SUA in umbrella agency w/L&C |

0 |

none |

centralized |

Ombudsmen are located in two state offices. |

|

District of Columbia |

legal agency |

3 |

nonprofit agencies |

decentralized |

|

|

State |

State Ombudsman Placement |

Number of Local Programs |

Local Ombudsman Placement |

Operation of Statewide Program |

Special Aspects of Program |

|

Florida |

independent SUA |

0 |

none |

centralized |

Governor-appointed volunteer ombudsmen serve on 12 district councils across the state. The volunteer ombudsmen are recruited and trained by a paid district coordinator who is not an ombudsman. District coordinators are hired and supervised by the state ombudsman. |

|

Georgia |

SUA in umbrella agency w/L&C |

17 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Hawaii |

independent SUA |

0 |

none |

centralized |

All ombudsmen are located in the state office. |

|

Idaho |

independent SUA |

7 |

AAAs |

decentralized |

The Office on Aging is considered an independent SUA located in the governor’s office. |

|

Illinois |

independent SUA |

18 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Indiana |

SUA in umbrella agency w/o L&C |

17 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Iowa |

independent SUA |

0 |

none |

centralized |

Volunteer advocates serve on care review committees in each nursing facility in the state. The volunteer advocates are appointed by the SUA director and report directly to the state ombudsman. Thirteen care review coordinators in the AAAs recruit and train the volunteers, but are not considered local ombudsmen. |

|

Kansas |

independent SUA |

0 |

none |

centralized |

Ombudsmen are located regionally. |

|

Kentucky |

SUA in umbrella agency w/L&C |

15 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Louisiana |

independent SUA |

25 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Maine |

legal agency |

0 |

none |

centralized |

Regional ombudsman work out of two locations. |

|

Maryland |

independent SUA |

19 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Massachusetts |

independent SUA |

27 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Michigan |

nonprofit agency |

8 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Minnesota |

independent SUA agency |

1 |

nonprofit |

combination |

A nonprofit citizens’ advocacy agency serves one region; all other regions are served by state regional employees. |

|

Mississippi |

SUA in umbrella agency w/o L&C |

10 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Missouri |

SUA in umbrella agency w/L&C |

10 |

variety |

decentralized |

The SUA is responsible for L&C. |

|

Montana |

SUA in umbrella agency w/o L&C |

11 |

AAAs |

decentralized |

|

|

Nebraska |

independent SUA |

1 |

AAAs |

combination |

The state ombudsman provides services directly in one area of the state. |

|

Nevada |

SUA in umbrella agency w/L&C |

0 |

none |

centralized |

Ombudsmen are located in two state offices. |

|

New Hampshire |

SUA in umbrella agency w/o L&C |

0 |

none |

centralized |

Ombudsman staff and volunteers are assigned to specific geographic regions and facilities. |

|

New Jersey |

other state agency |

0 |

none |

centralized |

All ombudsman staff work out of the state office. A volunteer program is currently being developed in cooperation with the SUA. |

|

State |

State Ombudsman Placement |

Number of Local Programs |

Local Ombudsman Placement |

Operation of Statewide Program |

Special Aspects of Program |

|

New Mexico |

independent SUA |

4 |

AAAs |

combination |

The state ombudsman provides services directly in one area of the state. |

|

New York |

independent SUA |

43 |

variety |

combination |

Forty-three AAAs operate local programs, directly or by contract, through nonprofit agencies. The rest of the state is served by the state ombudsman. |

|

North Carolina |

SUA in umbrella agency w/L&C |

18 |

AAAs |

decentralized |

|

|

North Dakota |

SUA in umbrella agency w/o L&C |

3 |

regional service agencies |

combination |

Local programs are located in 3 state regional service agencies. The state ombudsman covers the two remaining regions. |

|

Ohio |

independent SUA |

12 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Oklahoma |

SUA in umbrella agency w/o L&C |

11 |

AAAs |

decentralized |

|

|

Oregon |

other state agency |

0 |

none |

centralized |

Oregon is divided into 21 district programs, which are supervised by teams of volunteer leaders. The state ombudsman, aided by 3 field officers, appoints and directs all program participants. |

|

Pennsylvania |

independent SUA |

52 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Puerto Rico |

independent SUA |

10 |

AAAs |

decentralized |

|

|

Rhode Island |

independent SUA |

0 |

none |

centralized |

|

|

South Carolina |

SUA in umbrella agency w/o L&C |

7 |

AAAs |

combination |

The SUA is located in the governor’s office. Seven local programs, operated by AAAs, serve 9 regions; the state ombudsman covers the remaining region. |

|

South Dakota |

SUA in umbrella agency w/o L&C |

0 |

none |

centralized |

The state ombudsman supervises the ombudsman function in 26 state regional agencies. |

|

Tennessee |

independent SUA |

9 |

variety |

decentralized |

Local programs are located in state regional service agencies. |

|

Texas |

independent SUA |

28 |

variety |

decentralized |

|

|

Utah |

SUA in umbrella agency w/o L&C |

12 |

AAAs |

decentralized |

|

|

Vermont |

legal agency |

0 |

none |

centralized |

Vermont Legal Aide sponsors the state ombudsman program and employs all local ombudsmen, who are located in AAAs. |

|

Virginia |

independent SUA |

8 |

AAAs |

combination |

Eight local programs are operated by AAAs; the rest of the state is served by the state ombudsman. |

|

Washington |

nonprofit agency |

10 |

variety |

combination |

Under state law, a nonprofit citizens advocacy agency operates the state ombudsman program. Some areas of the state are served by community action programs, some by AAAs, and the rest by the state ombudsman directly. |

|

West Virginia |

SUA in umbrella agency w/L&C |

1 |

legal services agency |

decentralized |

|

|

State |

State Ombudsman Placement |

Number of Local Programs |

Local Ombudsman Placement |

Operation of Statewide Program |

Special Aspects of Program |

|

Wisconsin |

other state agency |

0 |

none |

centralized |

The state ombudsman program is located in the statutorily created Board on Aging and Long-Term Care. Ombudsmen are state employees located in regional offices and supervised by the state office. |

|

Wyoming |

legal agency |

0 |

none |

centralized |

The state ombudsman employs a regional ombudsman in the western part of the state. |

|

SOURCES: National Eldercare Institute, 1993b; AoA, 1994c; and IOM study site visits. |

|||||

Target Population

The LTC ombudsman program serves older residents of nursing facilities and B&C homes. It is estimated that 1,365,873 residents over age 65 reside in nursing facilities. They represent 92 percent of all nursing facility residents. Although older residents constitute a smaller percentage of all B&C residents (only 52 percent), a sizable number of older individuals (216,020) live in such facilities (Sirrocco, 1994). The number of nursing facility and B&C beds provides a measure of the scope of the ombudsman programs’ mandate. As shown in Table 2.2, in 1992, there were 1,714,720 nursing facility beds and 618,704 licensed B&C beds in the nation.

Human Resources

Paid Staff

Recent estimates of LTC ombudsman staffing put the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) paid staff at 865 (see Table 2.3).1 Average state-level staffing (i.e., not including any local staff) is estimated at 2.6 FTEs per state. The number of paid staff of local programs (i.e., not including any state-level staff) ranges from 1 to 153. Kautz (1994) estimated the average statewide staffing (i.e., including both state-level and local staff) to be 15.7 FTEs. Because the mean figure is influenced considerably by a few states with high staffing levels, the median is probably the most indicative measure. Median statewide staffing is 10 FTEs. The ratio of FTEs to beds ranges from 1 to 128 in South Dakota to 1 to 28,370 in New Jersey. The nationwide ratio of FTEs to beds is 1 to 2,698.

The OAA requires states to employ at least one person as the “State LTC Ombudsman,” who “shall serve on a full-time basis.” All states have named such a person, although the committee found that, in several states, that person’s time is not devoted solely to the program. For example, since the enactment of the 1992 OAA amendments, several states have named or are considering naming their state ombudsman to lead or coordinate the Elder Rights (Title VII)

TABLE 2.2 Number of Nursing Home and Board and Care Home Beds, by State, 1992

|

State |

Nursing Homea |

Board & Careb |

Total |

|

Alabama |

23,025 |

3,678 |

26,703 |

|

Alaska |

1,033 |

495 |

1,528 |

|

Arizona |

16,719 |

5,116 |

21,835 |

|

Arkansas |

23,790 |

4,027 |

27,817 |

|

California |

130,955 |

138,194 |

269,149 |

|

Colorado |

20,106 |

6,327 |

26,433 |

|

Connecticut |

30,118 |

3,176 |

33,294 |

|

Delaware |

4,867 |

430 |

5,297 |

|

District of Columbia |

3,129 |

1,837 |

4,966 |

|

Florida |

71,162 |

61,086 |

132,248 |

|

Georgia |

39,923 |

11,473 |

51,396 |

|

Hawaii |

3,415 |

2,632 |

6,047 |

|

Idaho |

5,804 |

2,198 |

8,002 |

|

Illinois |

100,557 |

8,482 |

109,039 |

|

Indiana |

58,993 |

9,589 |

68,582 |

|

Iowa |

35,391 |

6,895 |

42,286 |

|

Kansas |

27,664 |

1,694 |

29,358 |

|

Kentucky |

23,145 |

8,902 |

32,047 |

|

Louisiana |

37,496 |

307 |

37,803 |

|

Maine |

10,236 |

3,921 |

14,157 |

|

Maryland |

27,587 |

5,179 |

32,766 |

|

Massachusetts |

52,828 |

5,681 |

58,509 |

|

Michigan |

50,961 |

44,091 |

95,052 |

|

Minnesota |

45,073 |

10,003 |

55,076 |

|

Mississippi |

16,051 |

2,302 |

18,353 |

|

Missouri |

61,922 |

17,695 |

79,617 |

|

Montana |

6,495 |

1,043 |

7,538 |

|

Nebraska |

19,492 |

4,689 |

24,181 |

|

Nevada |

3,563 |

1,643 |

5,206 |

|

New Hampshire |

6,966 |

2,342 |

9,308 |

|

New Jersey |

44,314 |

12,426 |

56,740 |

|

New Mexico |

6,783 |

2,614 |

9,397 |

|

New York |

106,124 |

34,803 |

140,927 |

|

North Carolina |

35,174 |

23,862 |

59,036 |

|

North Dakota |

7,084 |

1,215 |

8,299 |

|

Ohio |

91,580 |

10,383 |

101,963 |

|

Oklahoma |

34,581 |

2,858 |

37,439 |

|

Oregon |

14,758 |

12,986 |

27,744 |

|

Pennsylvania |

89,963 |

43,039 |

133,002 |

|

Puerto Rico |

— |

— |

— |

|

State |

Nursing Homea |

Board & Careb |

Total |

|

Rhode Island |

10,222 |

925 |

11,147 |

|

South Carolina |

16,125 |

8,324 |

24,449 |

|

South Dakota |

8,251 |

704 |

8,955 |

|

Tennessee |

35,450 |

4,848 |

40,298 |

|

Texas |

122,078 |

9,366 |

131,444 |

|

Utah |

8,025 |

1,178 |

9,203 |

|

Vermont |

3,645 |

2,200 |

5,845 |

|

Virginia |

29,328 |

35,016 |

64,344 |

|

Washington |

29,241 |

17,716 |

46,957 |

|

West Virginia |

10,236 |

2,542 |

12,778 |

|

Wisconsin |

49,737 |

16,000 |

65,737 |

|

Wyoming |

3,555 |

572 |

4,127 |

|

Total |

1,714,720 |

618,704 |

2,333,424 |

|

SOURCES: aDuNah et al., 1993, Table 1 ; bHarrington et al., 1993, Table 7. |

|||

programs. This work involves such unrelated activities as insurance counseling and monitoring all cases of elder abuse, including abuse that occurs outside of nursing facilities or B&C homes.

Salaries of LTC ombudsmen vary greatly. A recent study found that one state ombudsman made $18,000 per year, whereas another made $56,000 (NORC, 1994a). The median salary range of a state ombudsman is $30,000-$35,000. No correlations were found between the state ombudsman’s salary and the size of the program, the ombudsman’s education or experience, or the program’s reputation for quality. The committee found that salaries of local ombudsmen were considerably lower than those of their state counterparts; most commonly, local ombudsmen were paid in the low $20,000s. The committee also found that most state and local programs had very little, sometimes no, clerical support.

Volunteers

Volunteers perform a variety of functions in the ombudsman program. Many volunteers are designated official representatives of the program and are

TABLE 2.3 Long-Term Care Ombudsman Human Resources, Paid Staff and Volunteers, by State

|

State |

Number of Paid Staff (FTEs) |

Ratio of Paid Staff to Bedsa |

Number of Volunteers |

Ratio of Paid Staff to Volunteers |

|

Alabama |

12 |

1:2,225 |

0 |

— |

|

Alaska |

1 |

1:1,528 |

12 |

1:12 |

|

Arizona |

7 |

1:3,119 |

125 |

1:18 |

|

Arkansas |

13 |

1:2,140 |

43 |

1:3 |

|

California |

153 |

1:1,759 |

1,325 |

1:9 |

|

Colorado |

21 |

1:1,259 |

50 |

1:2 |

|

Connecticut |

10 |

1:3,329 |

29 |

1:3 |

|

Delaware |

6 |

1:883 |

40 |

1:7 |

|

District of Columbia |

3 |

1:1,655 |

60 |

1:20 |

|

Florida |

12 |

1:11,021 |

219 |

1:18 |

|

Georgia |

33 |

1:1,557 |

60 |

1:2 |

|

Hawaii |

2 |

1:3,024 |

0 |

— |

|

Idaho |

14 |

1:572 |

0 |

— |

|

Illinois |

15 |

1:7,269 |

283 |

1:19 |

|

Indiana |

13 |

1:5,276 |

8 |

1:1 |

|

Iowa |

8 |

1:5,286 |

0 |

— |

|

Kansas |

4 |

1:7,340 |

0 |

— |

|

Kentucky |

27 |

1:1,187 |

275 |

1:10 |

|

Louisiana |

37 |

1:1,022 |

375 |

1:10 |

|

Maine |

3 |

1:4,719 |

5 |

1:2 |

|

Maryland |

17 |

1:1,927 |

124 |

1:7 |

|

Massachusetts |

30 |

1:1,950 |

323 |

1:11 |

|

Michigan |

21 |

1:4,526 |

69 |

1:3 |

|

Minnesota |

15 |

1:3,672 |

121 |

1:8 |

|

Mississippi |

8 |

1:2,294 |

200 |

1:25 |

|

Missouri |

20 |

1:3,981 |

335 |

1:17 |

|

Montana |

18 |

1:419 |

10 |

1:1 |

|

Nebraska |

1 |

1:24,181 |

15 |

1:15 |

|

Nevada |

5 |

1:1,041 |

0 |

— |

|

New Hampshire |

7 |

1:1,330 |

94 |

1:13 |

|

New Jersey |

2 |

1:28,370 |

29 |

1:15 |

|

New Mexico |

7 |

1:1,342 |

100 |

1:14 |

|

New York |

31 |

1:4,546 |

575 |

1:19 |

|

North Carolina |

18 |

1:3,280 |

0 |

— |

|

North Dakota |

1 |

1:8,299 |

0 |

— |

|

Ohio |

44 |

1:2,317 |

205 |

1:5 |

|

Oklahoma |

13 |

1:2,880 |

263 |

1:20 |

|

State |

Number of Paid Staff (FTEs) |

Ratio of Paid Staff to Bedsa |

Number of Volunteers |

Ratio of Paid Staff to Volunteers |

|

Oregon |

3 |

1:9,248 |

300 |

1:100 |

|

Pennsylvania |

31 |

1:4,290 |

10 |

— |

|

Puerto Rico |

9 |

— |

30 |

1:3 |

|

Rhode Island |

1 |

1:11,147 |

0 |

— |

|

South Carolina |

5 |

1:4,890 |

0 |

— |

|

South Dakota |

70 |

1:128 |

0 |

— |

|

Tennessee |

11 |

1:3,663 |

152 |

1:14 |

|

Texas |

27 |

1:4,868 |

570 |

1:21 |

|

Utah |

12 |

1:767 |

19 |

1:2 |

|

Vermont |

5 |

1:1,169 |

5 |

1:1 |

|

Virginia |

10 |

1:6,434 |

42 |

1:4 |

|

Washington |

9 |

1:5,217 |

240 |

1:27 |

|

West Virginia |

9 |

1:1,420 |

11 |

1:1 |

|

Wisconsin |

7 |

1:9,391 |

0 |

— |

|

Wyoming |

4 |

1:1,032 |

0 |

— |

|

Nationwide |

865 |

1:2,698 |

6,751 |

1:8 |

|

aCalculations are based on the number of beds found in Table 2.2. SOURCE: AARP, 1994a. |

||||

given all the rights and responsibilities afforded to paid ombudsmen. Other volunteers serve as “friendly visitors” and assist the ombudsmen in maintaining a presence in the facilities, keeping residents informed of their rights and of the LTC ombudsmen’s services, and identifying problem conditions, which they refer to a paid ombudsman for resolution. Many programs believe that the use of volunteers adds authenticity to the program and helps to keep it focused on the resident in a way that a typical government bureaucracy cannot.

The number of volunteers has more than doubled since 1982—from 3,306 in 1982 to 6,751 in 1994 (Schiman and Lordeman, 1989b; AARP, 1994a). Thirteen states reported no volunteer activity; California, with 1,325 volunteers, reported the most (AARP, 1994a).

Volunteer efforts are not without their costs, however. Programs must spend much time recruiting, training, and supervising volunteers. Paid staff-to-

volunteer ratios average 1:8 nationally and range from 1:1 in four states to a high of 1:100 (Oregon) (AARP, 1994a).

Funding

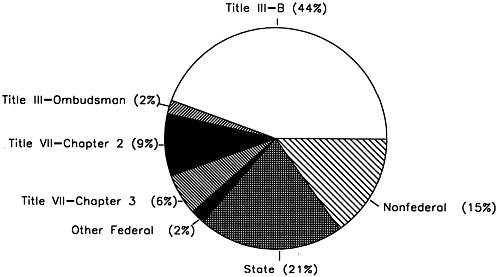

Funding for LTC ombudsman programs is patched together from multiple sources at the federal, state, and local levels (Figure 2.1 and Table 2.4). Most federal funding comes from Titles III and VII of the OAA: in FY 1993 this accounted for 61 percent of the total program funding of nearly $38 million. States are required to provide matching funds to their Title III allotment (at least 15 percent); no state match is required for Title VII allotments. Usually the states take this additional state funding from their own general revenues, but two states (Maine and Ohio) have instituted a nursing facility bed tax to help finance the program. The amount of funding contributed by states varies considerably: in FY 1993, for example, seven programs received no state dollars, whereas seven other programs received more than 50 percent of their budget from state funds. Overall, states’ contributions account for 21 percent of total program funding. Sources for other funding include AAAs, local governments, the United Way, and foundations. These other sources account for 15 percent of total program funding.

Several important factors govern the way that OAA monies for ombudsman activities are distributed to and within the states. Title III and VII monies are distributed to states through an interstate funding formula based primarily on the number of older individuals in the state. Within states, Title III monies are distributed to AAAs through an intrastate funding formula developed by the state that takes into account such factors as number of low-income minority older individuals, geographical distribution of older individuals, and number of older individuals with the greatest economic or social need. Title VII monies, however, are distributed at the discretion of the SUA through a different intrastate formula from Title III monies. Some states use formulas that rely on factors such as location and size of nursing facilities.

At the present time, SUAs and AAAs are required to expend, at a minimum, the same amount they spent on the LTC ombudsman program from all sources in FY 1991 (primarily Title III monies). Additional monies earmarked specifically for the ombudsman program became available in FY 1992 through an appropriation for Title VII, but states are prohibited from using these new monies to supplant funds that the program had before FY 1992 (when most funding for the ombudsman program came from Title III). Therefore, most states find the primary source of funding for the program in Title III monies. (See Chapter 6 for a discussion of the adequacy of program funding.)

TABLE 2.4 Long-Term Care Ombudsman Programs’ Amounts of Funding by Source, FY 1993, by State

|

|

Federal |

|

|||||||

|

State |

Title III Part B |

Title III Ombudsman |

Title VII Chapter 2 |

Title VII Chapter 3 |

Other Federal |

Total Federal |

State |

Other |

Total |

|

Alabama |

$57,744 |

|

$62,248 |

$8,752 |

$27,047 |

$155,791 |

$12,461 |

$190,707 |

$358,959 |

|

Alaska |

88,394 |

|

19,349 |

|

|

107,743 |

|

|

107,743 |

|

Arizona |

36,943 |

$53,302 |

20,220 |

|

|

110,465 |

116,000 |

|

226,465 |

|

Arkansas |

286,117 |

|

41,941 |

47,123 |

|

375,181 |

12,497 |

|

387,678 |

|

California |

1,130,353 |

339,993 |

361,495 |

413,191 |

|

2,245,032 |

2,019,256 |

1,742,938 |

6,007,226 |

|

Colorado |

420,550 |

|

25,228 |

|

9,582 |

455,360 |

26,222 |

43,896 |

525,478 |

|

Connecticut |

144,174 |

|

53,503 |

6,725 |

203 |

204,605 |

559,559 |

5,109 |

769,273 |

|

Delaware |

128,714 |

|

13,017 |

6,350 |

|

148,081 |

33,441 |

|

181,522 |

|

District of Columbia |

54,440 |

|

19,349 |

11,000 |

32,000 |

116,789 |

127,978 |

|

244,767 |

|

Florida |

314,995 |

|

239,803 |

269,431 |

47,921 |

872,150 |

19,733 |

470,045 |

1,361,928 |

|

Georgia |

611,709 |

|

77,484 |

87,058 |

|

776,251 |

401,385 |

63,708 |

1,241,344 |

|

Hawaii |

31,819 |

8,922 |

14,202 |

|

|

54,943 |

46,628 |

|

101,571 |

|

Idaho |

243,814 |

|

19,349 |

21,739 |

27,280 |

312,182 |

24,653 |

|

336,835 |

|

Illinois |

879,051 |

|

150,955 |

50,411 |

194,480 |

1,274,897 |

|

342,950 |

1,617,847 |

|

Indiana |

226,050 |

|

81,171 |

|

41,600 |

348,821 |

13,372 |

41,519 |

403,712 |

|

Iowa |

105,470 |

50,013 |

50,013 |

|

|

205,496 |

|

|

205,496 |

|

Kansas |

98,750 |

|

41,210 |

27,063 |

|

167,023 |

28,857 |

|

195,880 |

|

Kentucky |

365,649 |

|

56,579 |

63,570 |

|

485,798 |

110,125 |

191,713 |

787,636 |

|

Louisiana |

512,743 |

|

57,497 |

|

|

570,240 |

90,910 |

98,607 |

759,757 |

|

Maine |

55,181 |

|

20,110 |

|

|

75,291 |

48,465 |

3,246 |

127,002 |

|

Maryland |

125,000 |

|

61,631 |

|

|

186,631 |

|

|

186,631 |

|

Massachusetts |

1,668,004 |

|

98,661 |

|

136,676 |

1,903,341 |

97,980 |

|

2,001,321 |

|

Michigan |

53,360 |

|

141,229 |

|

40,549 |

235,138 |

448,167 |

209,006 |

892,311 |

|

Minnesota |

599,637 |

|

65,084 |

|

|

664,721 |

152,149 |

193,115 |

1,009,985 |

|

Mississippi |

334,888 |

|

30,692 |

11,616 |

26,009 |

403,205 |

29,147 |

30,525 |

462,877 |

|

Missouri |

376,477 |

|

57,099 |

75,770 |

|

509,346 |

107,322 |

153,818 |

770,486 |

|

Montana |

27,800 |

|

19,347 |

|

20,000 |

67,147 |

8,050 |

|

75,197 |

|

Nebraska |

26,696 |

|

27,327 |

|

26,939 |

80,962 |

9,535 |

|

90,497 |

|

Nevada |

$40,000 |

|

$12,646 |

|

$26,291 |

$78,937 |

$52,068 |

|

$131,005 |

|

New Hampshire |

96,422 |

$37,738 |

13,591 |

$11,260 |

48,757 |

207,768 |

50,358 |

|

258,126 |

|

New Jersey |

|

|

136,069 |

|

|

136,069 |

797,945 |

|

934,014 |

|

New Mexico |

146,996 |

|

19,889 |

22,346 |

|

189,231 |

76,042 |

$13,467 |

278,740 |

|

New York |

1,671,916 |

121,026 |

191,660 |

247,106 |

|

2,231,708 |

215,163 |

242,918 |

2,689,789 |

|

North Carolina |

627,838 |

|

93,161 |

97,391 |

|

818,390 |

105,091 |

82,669 |

1,006,150 |

|

North Dakota |

20,000 |

|

19,349 |

21,739 |

|

61,088 |

|

|

61,088 |

|

Ohio |

1,025,214 |

|

168,853 |

189,717 |

12,252 |

1,396,036 |

484,286 |

618,044 |

2,498,366 |

|

Oklahoma |

380,130 |

|

48,656 |

52,318 |

34,992 |

516,096 |

102,697 |

30,808 |

649,601 |

|

Oregon |

30,914 |

26,000 |

44,581 |

50,090 |

24,014 |

175,599 |

173,779 |

|

349,378 |

|

Pennsylvania |

1,033,199 |

|

288,397 |

|

|

1,321,596 |

182,327 |

249,001 |

1,752,924 |

|

Puerto Rico |

162,548 |

|

42,370 |

37,711 |

|

242,629 |

|

21,723 |

264,352 |

|

Rhode Island |

50,669 |

|

19,145 |

|

|

69,814 |

20,000 |

|

89,814 |

|

South Carolina |

77,850 |

|

45,926 |

965 |

|

124,741 |

7,161 |

14,322 |

146,224 |

|

South Dakota |

57,964 |

|

19,650 |

16,989 |

|

94,603 |

13,227 |

|

107,830 |

|

Tennessee |

455,417 |

|

73,635 |

82,734 |

|

611,786 |

|

75,615 |

687,401 |

|

Texas |

1,013,828 |

|

106,011 |

124,282 |

|

1,244,121 |

55,935 |

181,460 |

1,481,516 |

|

Utah |

25,754 |

|

27,174 |

19,374 |

22,887 |

95,189 |

21,095 |

30,586 |

146,870 |

|

Vermont |

164,334 |

|

22,792 |

6,974 |

24,000 |

218,100 |

3,921 |

2,808 |

224,829 |

|

Virginia |

123,157 |

|

61,426 |

24,544 |

629 |

209,756 |

78,407 |

177,004 |

465,167 |

|

Washington |

45,000 |

|

65,416 |

|

33,537 |

143,953 |

352,364 |

144,869 |

641,186 |

|

West Virginia |

126,035 |

|

33,183 |

36,745 |

|

195,963 |

233,659 |

1,734 |

431,356 |

|

Wisconsin |

65,000 |

|

40,000 |

|

12,900 |

117,900 |

353,100 |

|

471,000 |

|

Wyoming |

21,500 |

|

19,650 |

|

22,080 |

63,230 |

22,472 |

85,702 |

171,404 |

|

Total |

16,466,207 |

636,994 |

3,539,023 |

2,142,084 |

892,625 |

23,676,933 |

7,944,989 |

5,753,632 |

37,375,554 |

|

SOURCE: AoA, 1994c. |

|||||||||

FUNCTIONS OF THE LONG-TERM CARE OMBUDSMAN PROGRAM

The OAA legislates a wide-ranging scope of advocacy functions for the Office of the State LTC Ombudsman to perform both at the individual resident level and at the broader systems level. In performing these functions, the LTC ombudsmen must maintain relationships that are inherently full of tension. On the one hand, ombudsmen must often be highly critical of the facilities and agencies under their review; on the other hand, they must be able to work cooperatively with these parties to ensure that the resident is well served. Ombudsmen must also interact with an extensive array of program administrators and policymakers regarding extremely complex and often contradictory sets of laws, regulations, and policy and program instructions.

Resident-Level Advocacy

When working with individual residents, ombudsmen’s responsibilities include: ensuring residents have regular and timely access to the program, investigating and resolving complaints, working cooperatively with other agencies, and providing technical assistance and training to representatives of the program.

Ensuring that Residents Have Regular and Timely Access to the Program

The regular presence of persons from outside of facilities has been identified as an important factor in improving quality of care and quality of life in facilities (IOM, 1986; Barney, 1987; Feder et al., 1988; Glass, 1988; Cherry, 1991, 1993; Nelson, 1993; Arcus, 1994). Many LTC ombudsmen and other LTC professionals think that proactive, routine on-site presence is essential. They argue that it builds awareness of the program, establishes resident confidence, detects concerns about residents’ conditions before these become serious, and creates and maintains positive working relationships with the facility administration and staff. Such factors as increased percentage of residents with mental incapacities, isolation of residents from families, and difficult access to telephones strengthen the claim for continuous, predictable visitation by LTC ombudsmen.

States often set standards for how often a facility should be visited by an ombudsman or volunteer (Table 2.5). Kautz (1994) found that, of the 36 states he studied, 29 had instituted visitation standards, but only 18 of these states generally met their standard across all facilities. None of the states that had

instituted a weekly routine visit standard was able to achieve that goal across all facilities. In some states where ombudsmen are concentrated around certain large cities, the state reported that some areas achieved a 100 percent annual visitation rate but that others were not visited at all (AoA/OIG, 1993).

The frequency of visitation is closely related to the number of paid ombudsman staff and their proximity to facilities. In Kautz’s study (1994), of the 17 states with the highest visitation rate, 9 reported a staff of more than 0.75 FTEs per 1,000 beds; only 5 of the 17 states with the lowest visitation rate had this level of FTEs per bed. Kautz also reviewed the relevance of commuting distance and visitation rates. He found that 15 of the 17 states with the highest visitation rates reported that more than 80 percent of the facilities in the state had a certified ombudsman within a one-hour commute; by contrast, only 4 of the 17 states with the lowest rates had an ombudsman within one hour of 80 percent of all facilities.

A low routine visitation standard may not reflect the actual visitation rate or ombudsmen presence in LTC facilities (Chaitovitz, 1994b). Several state LTC ombudsmen stated that their overall visitation standard was low, but that they often visited certain problem facilities on a weekly basis for months in order to respond to complaints. Other visits were made but were not necessarily counted toward meeting the visitation standard, for example, visits to train facility staff and organize resident or family councils.

Kautz (1994) found that 9 states had instituted no nursing facility visitation standard at all, 6 only visited annually, 9 visited quarterly, 4 visited monthly, and 8 visited weekly or biweekly. B&C homes are visited far less frequently than nursing facilities; 13 states had no visitation standard at all, 9 only visited annually, 5 visited quarterly, 3 visited monthly, and 6 visited weekly or biweekly.

Investigating and Resolving Complaints

Throughout the nation, LTC ombudsmen advocate on behalf of residents of LTC facilities, including those who cannot speak for themselves, and work to empower all residents and their agents to be stronger advocates on their own behalf. However, state and local programs differ in the way this end is achieved. In many instances, individual ombudsmen within the same local program differ in the way they operate. Some programs and individual ombudsmen assume an aggressive and adversarial, or “contest,” approach to their work, whereas others take a more neutral, or “collaborative,” approach (Nelson, 1993).

Ombudsmen may play a variety of roles in their efforts to resolve complaints. These include four main types—friendly visitor, mediator, educator, and advocate (National Center for State LTC Ombudsman Resources, 1992).

TABLE 2.5 Visitation Standards, by State

Friendly Visitor. An ombudsman may simply provide companionship or social activity to a resident. Some providers feel that this is the most legitimate and helpful role an ombudsman can assume. By contrast, most ombudsmen, while acknowledging that the friendly visiting function may be an important step in getting to know residents and establishing trust, would hardly view this as their primary role.

Educator. An ombudsman may work to educate residents, families, facility staff, friends, and potential consumers about their rights and responsibilities in a facility. An ombudsman must, therefore, have a working knowledge of current federal and state residents’ rights in order to answer questions. Ombudsmen also may provide information to concerned individuals who wish to advocate for themselves, but do not know how to go about it. Handbooks (e.g., “How to Select a Nursing Home” or “Resident Rights Handbook”) can be used to provide supplementary information.

Mediator. An ombudsman may serve as a mediator between residents and staff, government agency, other residents, or family. In this role, the ombudsman may act as a spokesperson for the resident, communicating their concerns in an effort to resolve the problem. In this role, ombudsmen do not impose their own answers but help those involved to find and agree upon a mutually acceptable solution.

Advocate. An ombudsman may work actively on behalf of a resident in resolving complaints that have been substantiated and require specific strategies to alleviate the problem. Advocacy may mean negotiating with an administrator or other staff, filing a complaint on behalf of the resident, working with a residents’ council, representing the interests of residents before governmental agencies, or seeking administrative, legal, and other remedies. Although “advocate” is often used as the generic term for ombudsmen, in the context of roles it has a very different meaning and function.

The primary activity required of LTC ombudsmen by the OAA and clearly performed by the program is the identification, investigation, and resolution of individual complaints relating to the residents of LTC facilities. The total number of complaints received by LTC ombudsmen increased 94 percent, from 102,231 to 197,820, between 1988 and 1993 (Schiman and Lordeman, 1989a; AoA, 1994c). More than 154,400 people lodged complaints with the LTC ombudsmen in FY 1993. About 75 percent of all complaints were lodged against nursing facilities, 16 percent against B&C facilities, 3 percent against regulatory and reimbursement agencies, and 6 percent against others (such as family members). Many of the complaints dealt with resident care (35 percent) and resident rights (17 percent) (AoA, 1994c).

When numbers of complaints are analyzed in terms of the number of LTC beds served by programs, complaint rates vary widely across states (Table 2.6). Nationwide, ombudsmen received 85 complaints per 1,000 LTC beds; the median is 67; the range is 14 in Iowa and North Dakota to 743 in the District of Columbia.

The General Accounting Office (GAO) observed similar variation in the 1988 complaint data and concluded that ombudsman programs may operate quite differently in different states. The GAO found that the rate of complaints received may be determined by the use of volunteers, the number of B&C residents served by the programs, the emphasis placed by programs on reaching B&C homes, the varying definitions of complaints used by the states, and the aggressiveness of programs in seeking out problems and identifying residents with complaints (GAO, 1992b).

Kautz (1994) found a positive correlation between routine visitation rates and number of complaints per bed. Of the states with the highest one-third of complaints per bed, 81 percent routinely visited more frequently than once a year, whereas 67 percent of those in the middle third did so, and only 36 percent of those in the lowest third did so. Kautz found notable exceptions to these relationships, however. Ohio, where visits take place at a relatively high rate, receives only 35 complaints per 1,000 beds, whereas Delaware, where no routine visits take place, experiences one of the highest complaint rates (195 complaints per 1,000 beds) in the nation. Some ombudsmen believe that routine visitation may deter poor care and conditions and, thereby, decrease the number of complaints (Arcus, 1994). They also suggest that, where few human resources are available, ombudsmen place less emphasis on complaint activity and more often seek to carry out their missions by educating and empowering residents, and these efforts are not reflected in complaint data.

Working Cooperatively with Other Agencies

As in more traditional ombudsman models, much of the work done by the LTC ombudsmen involves working with government agencies to improve residents’ situations and the LTC system. Many governmental agencies are involved with regulating and reimbursing both nursing facilities and B&C homes and protecting the residents in both types of facilities. Such agencies include Health Care Financing Administration, SUAs, AAAs, departments of health, divisions of licensure and certification, adult protective services (APS), professional boards (e.g., Board of Nursing Home Administrators), police, and district attorneys. Advocacy organizations such as protection and advocacy systems (P&As), as well as citizens’ groups, are also involved in providing oversight and advocacy to residents in these facilities. The interactions between

TABLE 2.6 Long-Term Care Ombudsman Complaints per 1,000 Beds, by State

|

State |

Complaints |

Complaints per 1,000 Bedsa |

|

Alabama |

1,443 |

54 |

|

Alaska |

368 |

241 |

|

Arizona |

1,817 |

83 |

|

Arkansas |

443 |

16 |

|

California |

46,777 |

174 |

|

Colorado |

8,613 |

326 |

|

Connecticut |

2,261 |

68 |

|

Delaware |

1,034 |

195 |

|

District of Columbia |

3,691 |

743 |

|

Florida |

7,035 |

53 |

|

Georgia |

3,464 |

67 |

|

Hawaii |

274 |

45 |

|

Idaho |

934 |

117 |

|

Illinois |

4,329 |

40 |

|

Indiana |

2,648 |

39 |

|

Iowa |

611 |

14 |

|

Kansas |

2,856 |

97 |

|

Kentucky |

4,042 |

126 |

|

Louisiana |

2,517 |

67 |

|

Maine |

316 |

22 |

|

Maryland |

2,388 |

73 |

|

Massachusetts |

10,463 |

179 |

|

Michigan |

6,559 |

69 |

|

Minnesota |

2,658 |

48 |

|

Mississippi |

344 |

19 |

|

Missouri |

8,128 |

102 |

|

Montana |

809 |

107 |

|

Nebraska |

3,438 |

142 |

|

Nevada |

3,297 |

633 |

|

New Hampshire |

1,165 |

125 |

|

New Jersey |

3,781 |

67 |

|

New Mexico |

1,445 |

154 |

|

New York |

3,485 |

25 |

|

North Carolina |

2,323 |

39 |

|

North Dakota |

117 |

14 |

|

Ohio |

3,530 |

35 |

|

Oklahoma |

3,416 |

91 |

|

Oregon |

5,967 |

215 |

|

Pennsylvania |

6,696 |

50 |

|

Puerto Rico |

1,451 |

— |

|

Rhode Island |

1,079 |

97 |

TABLE 2.6 Continued

|

State |

Complaints |

Complaints Per 1,000 Bedsa |

|

South Carolina |

2,338 |

96 |

|

South Dakota |

405 |

45 |

|

Tennessee |

2,639 |

65 |

|

Texas |

11,302 |

86 |

|

Utah |

682 |

74 |

|

Vermont |

531 |

91 |

|

Virginia |

953 |

15 |

|

Washington |

5,497 |

117 |

|

West Virginia |

1,277 |

100 |

|

Wisconsin |

3,521 |

54 |

|

Wyoming |

663 |

161 |

|

Total/Average |

197,820 |

85 |

|

a The number of beds can be found in Table 2.2. SOURCE: AoA, 1994c. |

||

the ombudsman program and three of these programs—licensure and certification, APS, and P&As—are described in more detail below.

Licensure and Certification. The ombudsman program was created, in part, to address some of the limitations and shortcomings of the regulatory system. Initially, many ombudsman programs spent considerable effort in developing memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with regulators to clarify the responsibilities of each party. Over the years and continuing today, however, the relationship between ombudsmen and licensure and certification staff has sometimes been marked with frustration and even confrontation rather than understanding and clarity about the actions each should take (Buford, 1984; Chaitovitz, 1994b). Ombudsmen and others cite evidence that most surveys are inadequate, enforcement is rare, and information about specific facilities (the availability of which is required by law) is not easily accessible to ombudsmen or the public (IOM, 1986).

Because ombudsmen and regulators operate within differing organizational structures and under separate protocols for evidence and reporting, ombudsmen frequently encounter difficulties in obtaining the level of support for enforcement that they feel is warranted to remedy problems in the care and treatment of residents. For example, ombudsmen may witness poor care or conditions first

hand or their investigations may turn up clear evidence of violations. Yet when regulatory investigators respond to complaints, they may report finding no evidence and therefore cite no violations. Regulators point out that they must adhere to strict rules of evidence, and these often preclude citing a violation based upon an eyewitness report.

The 1987 legislative changes referenced earlier have strengthened links between the ombudsman programs and regulators. For instance, federal regulations require that regulators contact ombudsmen early in the survey of any Medicare or Medicaid facility so that ombudsmen may share information with surveyors on complaints and conditions in the facility.2 Because these visits are scheduled on short notice, the ombudsmen sometimes cannot rearrange their schedules to accommodate such sharing of information. Also, the ombudsmen’s data systems typically cannot retrieve facility-specific complaint data in the short time they are given to provide such information to surveyors. Additionally, federal law also allows ombudsmen to attend the exit conference as observers at the close of the survey. Several states report that staff and volunteer shortages curtail ombudsman involvement in this activity. For example, Kansas’ annual report (KDOA, 1993) noted that a representative of the program was able to attend none of the 600 exit conferences held in the state (Kansas has a FTE to bed ratio of 1:7,340).

A few states conduct joint training sessions with licensing agencies. In at least one state, the state ombudsman sits on the advisory board of the licensing agency and volunteer ombudsmen sit in on surveyors’ interviews of residents during the survey. In other states, the licensing agency is represented on the ombudsman advisory council and local ombudsmen hold regular meetings with survey agency staff.

Currently, survey data must be gathered from hard copies provided by cooperative regulatory agencies. Ombudsmen suggest that, when such data can be provided to ombudsmen in electronic form, they will be more capable of providing to the public clear explanations of facility track records. This is currently being done in Indiana: LTC ombudsmen are equipped with the same laptop computers as surveyors, and they have instant access to survey data for all facilities in the state. Another positive development has occurred in Massachusetts where the two programs have ended years of bitter opposition and have begun to work cooperatively. Complaints lodged by Massachusetts ombudsmen are now given priority for investigation by the licensure and certification agency. The state ombudsman and the head of licensing and

certification have made several joint visits to facilities and plan to continue to do so in the future.

Adult Protective Services. Although not federally mandated to do so, most states have APS units. These units generally investigate instances of abuse, neglect, and exploitation of anyone over age 18 and provide protective services to those who are found to be maltreated. How these various units operate throughout the country varies considerably from state to state. Some are operated by the SUA, others by the social service department. In at least four states, APS is expressly prohibited from investigating complaints about the residents of LTC facilities; in many others, the committee found their involvement in LTC facilities to be very limited.

Because both LTC ombudsman and APS workers receive complaints regarding abuse, neglect, and exploitation of vulnerable older people, the responsibilities of the two programs overlap somewhat. Their roles in resolving these types of complaints are quite different, however. APS workers act as agents of the state, whereas LTC ombudsmen act as agents of the resident. When the two programs interact, APS workers and LTC ombudsmen work jointly on cases, make referrals, and attend joint staff training and meetings. In the canvass conducted by Chaitovitz (1994b), 23 state LTC ombudsman programs (n=50), or about half, reported good relations with APS. Only one state LTC ombudsman cited a poor or hostile relationship. Being housed within the same agency frequently enhances good relationships: 13 LTC ombudsman programs are located in the same agency as APS, and 9 of these programs report close or excellent relationships (Chaitovitz, 1994b). In several states, some LTC ombudsmen also have APS responsibilities.

Protection and Advocacy Systems. P&As are established by federal law in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories to protect the legal and human rights of individuals with disabilities. P&As serve four distinct populations: (1) persons with developmental disabilities; (2) persons with mental illness; (3) persons covered by the Rehabilitation Act of 1978; and (4) through the 1992 amendments to the Rehabilitation Act, all persons with disabilities who are not eligible for services under the other three programs.

P&As investigate and negotiate problems faced by persons with disabilities (such as discrimination, denial of benefits, and abuse and neglect), providing information, legal counsel, and representation, and promoting legislative and administrative changes to benefit persons with disabilities. To date, much of their efforts have focused on younger persons with disabilities, particularly those who are mentally ill or developmentally disabled, rather than older disabled individuals. However, many individuals typically served by the program are aging, and since the P&As mandate was expanded under the 1992 Rehabilitation Act amendments, the number of older clients is growing. Of over 70,000

individuals served by P&As in FY 1992, nearly 6,000 (9 percent) were age 60 or older (NAPAS, 1992).

The OAA requires the Office of the State LTC Ombudsman to coordinate ombudsman services with these organizations since they share similar concerns and mandates regarding such matters as statutes and regulations affecting the disabled, inadequate care in LTC facilities, and resident rights issues such as improper discharges and placement of individuals in inappropriate environments (although there is no similar mandate for P&As to coordinate with ombudsmen).

The 1992 survey of 20 state ombudsman programs (AoA/OIG, 1993) revealed several methods for coordination, including joint meetings, MOUs, joint training, and referral by the ombudsman to the P&As. In Colorado, the state LTC ombudsman program resides within the same agency that houses the P&As. The Louisiana ombudsman has developed a unique relationship with its P&As, the Advocacy Center for the Elderly and Disabled, or ACED (Kautz, 1994). The SUA and Office of the State LTC Ombudsman contract with ACED for legal support for state and local ombudsmen and LTC residents. Local ombudsmen have access to an attorney who is a full-time employee of ACED and a specialist in nursing facility and elder law. Not only has ACED pursued various remedies on behalf of residents and assisted the program in legislative and administrative systemic advocacy, but the relationship has also facilitated coordination activities between ombudsmen and ACED staff attorneys working on behalf of mentally ill or disabled nursing facility residents.

Coordination and cooperation are not universal, however. Several ombudsmen report that the P&As in their states give priority to those who live in the community or to school-age children (Chaitovitz, 1994b). These P&As maintain little, if any, involvement with residents of institutions. In addition, differences in philosophy and strategies may make coordination less desirable, as some state P&As take a more adversarial and litigious approach to advocacy than do ombudsmen.

Providing Technical Assistance and Training to Representatives of the Program

To fulfill their responsibilities, ombudsmen must have a thorough and up-to-date knowledge of many topics—the laws and regulations governing nursing facilities and B&C homes, investigation and mediation techniques, geriatrics and the medical and emotional needs of persons with disabilities, and the like. Both state and local ombudsmen provide training—initial and ongoing—and technical assistance to ensure that program representatives are as well prepared as possible. Additionally, since 1988, AoA has supported a national resource center for the LTC ombudsman program (the National Ombudsman Resource Center) whose mission is to train, provide technical assistance, and disseminate information.

The center is currently sponsored jointly by the National Citizen’s Coalition for Nursing Home Reform and the National Association of State Units on Aging.

To ensure that ombudsmen have a core level of knowledge to carry out their responsibilities, in the 1992 amendments to the OAA, Congress mandated AoA to establish procedures for the training of ombudsman program representatives, including unpaid volunteers. At the time of this writing, no such procedures have been established, however (see further discussion in Chapter 3).

Systems-Level Advocacy

In addition to working on individual cases and complaints, ombudsmen must address and attempt to rectify the broader or underlying causes of problems for residents of LTC facilities. When working on the systems level, ombudsmen advocate for policy change by evaluating laws and regulations, providing education to the public and facility staff, disseminating program data, and promoting the development of citizen organizations and resident and family councils.

Evaluating Laws and Regulations

The OAA directs state and local ombudsmen to analyze, comment on, recommend changes in, and monitor the development and implementation of laws affecting residents. Ombudsmen typically achieve this requirement through legislative, judicial, or administrative advocacy.

Legislative advocacy. Most ombudsmen work directly with legislators to advocate on behalf of residents. For example, the West Virginia state ombudsman lobbied successfully for a new guardianship law. The law guarantees residents and others the ability to pursue the “least restrictive alternative” by allowing for the designation of “limited” services for guardians and conservators, who are appointed by the court to handle a person’s personal affairs. Ombudsmen also lobby on the federal level through their membership association, the National Association of State LTC Ombudsman Programs (NASOP). NASOP members worked extensively on the 1992 reauthorization of the OAA that led to the creation of the new elder rights title.

Judicial advocacy. Sometimes ombudsmen make use of the judicial process to advocate on behalf of residents. The District of Columbia ombudsman program, for instance, successfully sued the city government in order to end the practice of distinguishing between skilled and intermediate levels of care and to bring local laws regulating Medicare and Medicaid facilities into compliance with

the 1987 Nursing Home Reform Law. The Florida state ombudsman program employs a “legal advocate” who, although he has never directly filed a lawsuit on behalf of a resident, has written numerous amicus briefs and legal articles in support of residents’ rights.

Administrative advocacy. Less visible, but equally effective, systemic advocacy may occur within the administrative rule-making process or during policy implementation. In Oklahoma, for example, the ombudsman helped convene a series of meetings with six different state divisions to develop a system of intermediate sanctions for nursing facilities. The Connecticut state ombudsman worked with other agencies in monitoring the implementation of a law against Medicaid discrimination in nursing facility admissions. The Michigan ombuds-man program convinced the state Medicaid agency to change its reimbursement policy to cover either disposable or cloth diapers for nursing facility residents, at the resident’s choice, in order to protect the dignity and privacy of incontinent residents.

Providing Education to the Public and Facility Staff

Many LTC ombudsmen have invested considerable resources in disseminating information about LTC and raising public interest in quality of life in facilities. The Office of the Inspector General (1991a) found that the 12 programs it termed the most successful “make themselves very visible in the aging community” through the use of posters, brochures, toll-free numbers, community outreach efforts, media spots, and inservice training for facility staff. These programs also regularly inform new facility residents of their rights and of the role of the ombudsman. States with limited capacity to visit facilities often enhance their effectiveness by offering statewide telephone hotlines. Virginia, for example, answered 8,930 requests for information made to its hotline in 1992 (VDOA, 1993).

Many state and local LTC ombudsmen address public meetings and support groups. They use such appearances not only to discuss with the public the current issues in quality of care and quality of life but also to recruit volunteers for their programs. Moreover, they sometimes use public forums to develop support for legislative advocacy. LTC ombudsmen provide information on such subjects as how to select a nursing or B&C home, how to contact the ombudsman or regulatory agencies, new laws governing facilities, and state-of-the-art treatment practices such as reducing restraint use.

Training of nursing facility and B&C home staffs and hospital discharge planners is another of the educational activities of LTC ombudsmen. Such audiences have found ombudsmen helpful in developing an understanding of residents’ rights and in discussing creative means of improving care and living

environments. California hired a public relations firm to publicize its program and produced television commercials and public service announcements (OIG, 1991 a). Texas and Massachusetts recruited their governors and other well-known persons to appear in public service announcements about their programs (OIG, 1991a).

Disseminating Program Data