1

Overview of Existing Offshore Structures and Removal Regulations

In 1946 the first exploratory well was drilled on the outer continental shelf (OCS) of the Gulf of Mexico, about 30 miles south of Morgan City, Louisiana. In 1947 the first commercially successful well was drilled from a fixed platform in about 16 feet of water, 12 miles south of Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana. The platform was built of timbers and wooden pilings. Today on the U.S. Gulf of Mexico OCS there are about 3,800 platforms in water depths ranging from less than 10 feet to nearly 3,000 feet.1

This report concerns the removal of platforms in OCS waters. It does not include the removal of more than 1,000 structures in state waters off the coast of Louisiana and Texas, almost all of which are installed in water depths of less than 35 feet. Most of these are small structures that support one to four wells and are relatively inexpensive to remove.

The platforms in use on the OCS today range from a simple vertical caisson (a single pile with a minimal deck) supporting one well in shallow water to the tension-leg platform Auger, located in 2,860 feet of water in the western Gulf of Mexico. A typical OCS platform supports numerous individual wells drilled directionally from the platform to bottom-hole targets thousands of feet away.

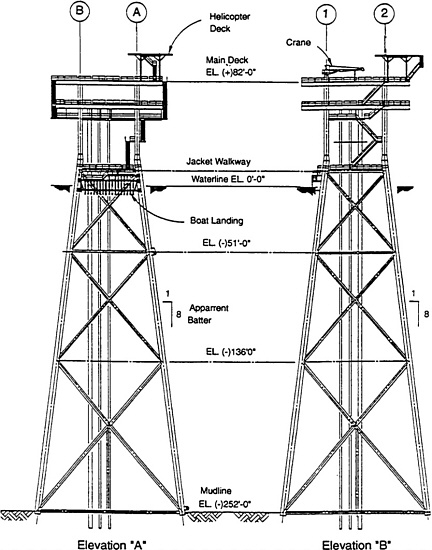

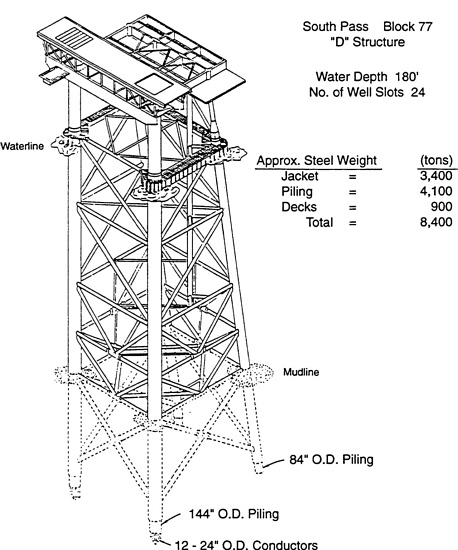

Conventional platforms are secured to the seafloor by steel pipes called piles (or pilings) driven through the legs of tubular frames called jackets. Only the upper portions of the jacket are visible above the water surface. The deck portion of the platform rests on top of the jacket. Most decks are multilevel structures that support drilling rigs, production equipment, crew quarters, and serve various other functions. The deepest conventional fixed platform is Shell 's Bullwinkle platform, which is located in 1,350 feet of water in the central Gulf of Mexico.

EXISTING PLATFORMS

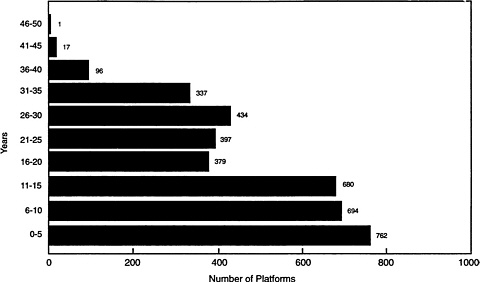

The focus of this report is the removal of older platforms in relatively shallow water (less than 300 feet). Figure 1-1 shows the age distribution of existing platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. Approximately one-fourth of the platforms in the OCS region of the Gulf of Mexico are more than 25 years old and have reached or exceeded their design life. These older platforms, and some newer platforms in short-lived fields, will require removal in the near future. Larger platforms in deep water (more than 300 feet) will require highly sophisticated removal methods; but they are few in number, and most of them are not expected to be removed for many years.

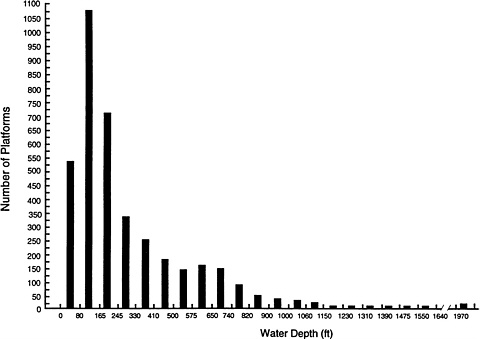

To date (through 1995) the only platforms removed from federal waters have been in the Gulf of Mexico. Because there are no existing platforms on the Alaska OCS or the Atlantic OCS, and only 23 on the Pacific OCS, this study is focused on platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. Figure 1-2 charts the distribution of existing platforms, including free-standing caissons, by water depth. Both caisson and other platform removals have been catalogued since 1985. Of the 900 or so platforms removed, approximately 30 percent were caissons (MMS, 1994); more than 95 percent of these caissons were in 100 feet of water or less. About 70 percent of the total were in 100 feet of water or less.

Platform Types and Configurations

The types of platforms and range of configurations vary widely. Platforms are designed to be used under specified environmental conditions and operating loads. In shallow water, the intended use may be simply to provide protection for a single well, as with a single-well caisson or multipile well-protector platform. Oil and gas produced from single caissons and well protectors are transported through in-field flow lines to gathering platforms where they are metered, processed, separated, and sold. In deeper water, a single large platform may be used to support both drilling and production of several wells. Platforms may also be used to house production personnel, gas compressor stations, oil storage tanks, or

|

1 |

Technical note: The U.S. offshore oil and gas industry and associated support industries use the U.S. customary measurement system for water depths (feet) and equipment diameters (inches). In this report, this system (feet and inches) is used in all discussions and data. |

pipeline junction and metering facilities. The overwhelming majority of platforms are intended for drilling and production.

Environmental factors that influence platform design include water depth; soil strength; and wind, wave, and current loads. Operating loads include the weight of production equipment for processing oil or gas. If platform rigs are required, drilling loads must also be taken into account.

Although it is difficult to sort all platform configurations into categories, most platform types may be characterized as follows:

-

free-standing caissons with well(s)

-

well-protector jackets

-

braced caissons with wells

-

conventionally piled platforms with wells

-

conventionally piled platforms without wells

-

skirt-piled platforms

-

special application platforms (e.g., mud slide resistant, wells in legs, deep-water structures)

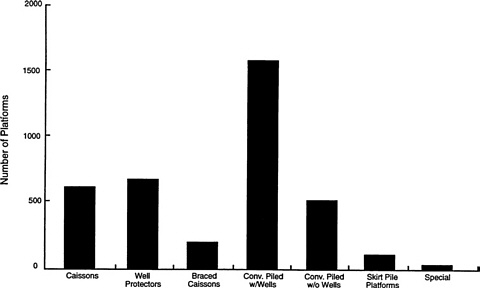

The distribution of platform types presently standing in OCS waters is shown in .

Free-Standing Caisson with Well(s)

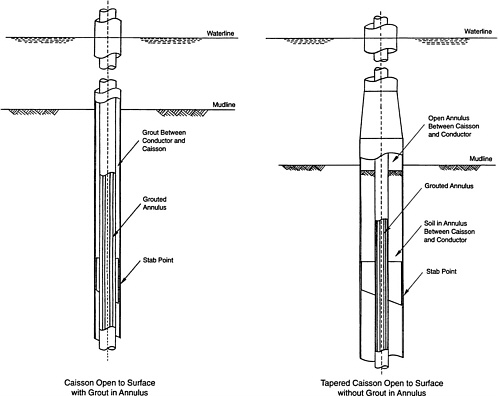

There are more than 600 free-standing caissons with wells, which comprise 16 percent of the platforms on the Gulf of Mexico OCS. Most are located in 100 feet of water or less. The purpose of most caissons is simply to protect wells from damage. Most free-standing caissons are single-diameter steel pipes that range from 36 inches to 96 inches in diameter. The caisson is driven into the soil to a sufficient depth to support itself and to resist environmental loads under storm conditions. The thickest section of the steel pipe is at or slightly below the sea floor at the point of greatest stress from wave and current loading. Wells are inside the caissons and consist of a variety of casing strings that may or may not be cemented together. Figure 1-4 shows an example of a caisson with a well with three casing strings. In smaller-diameter caissons the annulus between the well and caisson are cemented, but in larger-diameter caissons (60 inches to 96 inches) annuli are not usually cemented.

Another type of free-standing caisson is the tapered caisson (also figure 1-4). In deeper water these caissons may be 14 feet in diameter at the mudline and tapered to 6 feet at the water surface. Tapered caissons may support three wells or more. At these depths, tapered caissons usually have 2-inch to 3.5-inch-thick walls at and below the mudline. The procedures for removing a 36-inch-diameter caisson in 25 feet of water are different from the procedures for removing a 14-foot-diameter caisson with three partially cemented wells in 200 feet of water.

Well-Protector Jackets

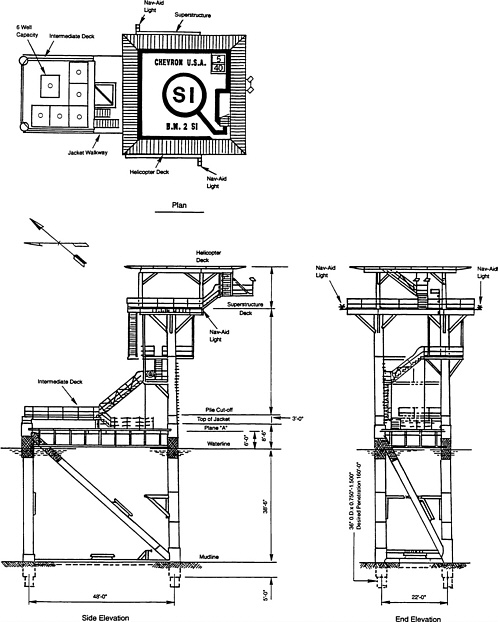

Well-protector jackets comprise a second type of platform. These platforms are multipiled jackets, with or without decks, that do not support drilling or production equipment (figure 1-5). The pilings are generally small in diameter (up to 30 inches) and are used in shallow water (up to about 100 feet). Well-protector jackets are used to protect wells (generally no

FIGURE 1-3 Distribution of existing platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. Source: MMS (1994, 1995).

FIGURE 1-4 Examples of caissons with wells. Source: Courtesy of Twachtman Snyder & Thornton, Inc.

more than four or six). The wells are often outside the piling, but they may be drilled through the piling. The oil and gas from well-protector jackets are transported through flow lines connected to a production platform. There are 650 well-protector jackets remaining on the Gulf of Mexico OCS, most of them in 100 feet of water or less (MMS, 1994, 1995). Well-protector jackets comprise 17 percent of the platforms remaining in the Gulf of Mexico.

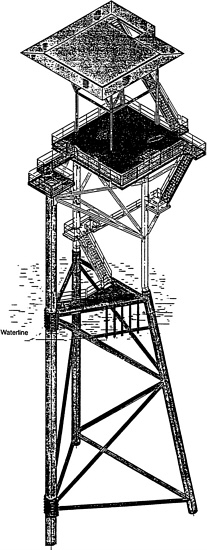

Braced Caissons with Well(s)

“Braced caissons with well(s)” is a term that describes most minimal platforms. Minimal platforms are useful for developing some economically marginal fields. In some minimal platforms, the well or caisson is used as one leg of a tripod; the other two may be conventionally piled legs (figure 1-6) or skirt piles that terminate below the water surface (figure 1-7). Skirt piles are almost always grouted to the skirt pile sleeve. Braced-caisson platforms can support a few wells, generally no more than three or four, and can be used in water up to 300 feet deep. Most braced-caisson platforms are in 50 to 200 feet of water. More than 200 have been built and installed since 1986; very few have been removed.

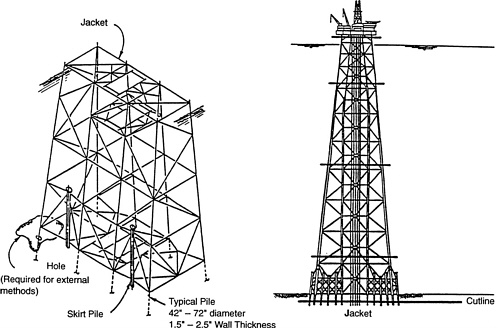

Conventionally Piled Platforms with Wells

The most common type of offshore structure in the Gulf of Mexico OCS is the conventionally piled platform with wells. In these structures, the pilings are driven through the legs of the jackets into the seabed. The number of piles can vary from three to eight or more (figure 1-8). The pile diameter can be as small as 24 inches (or smaller) or as large as 96 inches, depending on design requirements. The pile-to-jacket annulus in conventionally piled platforms is sometimes grouted. Mud mats near the bottom of a jacket provide temporary support until the piles are installed. In many cases the jacket is installed over one or more exploratory wells; several more development wells are then drilled through conductor slots in the jacket. There can be as few as one or two wells or as many as sixty. There are approximately 1,600 platforms of this type remaining in the Gulf of Mexico at all water depths. Conventionally piled platforms comprise 42 percent of the total.

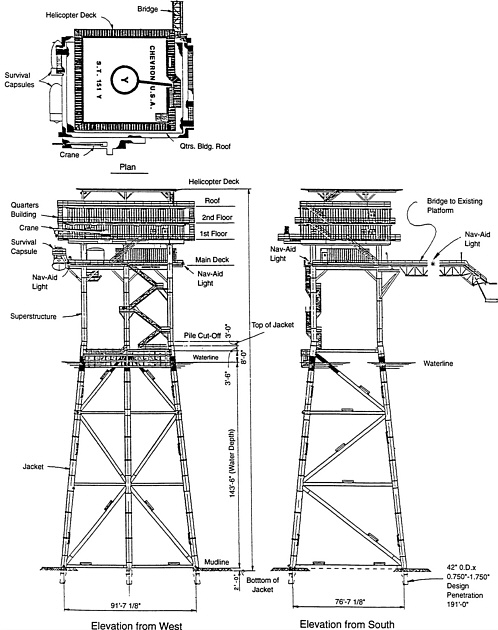

FIGURE 1-5 Well-protector platform. Source: Courtesy of Chevron U.S.A., Inc.

Conventionally Piled Platforms without Wells

Conventionally piled platforms without wells are used to house personnel (figure 1-9) and to support gas compressor stations, production equipment, oil storage tanks, or pipeline junction or metering facilities. Although no wells are located on these platforms, the design considerations are similar to conventionally piled platforms with wells. Platforms without wells are usually located in water less than 300 feet deep. There are about 500 of these platforms, approximately 13 percent of the total.

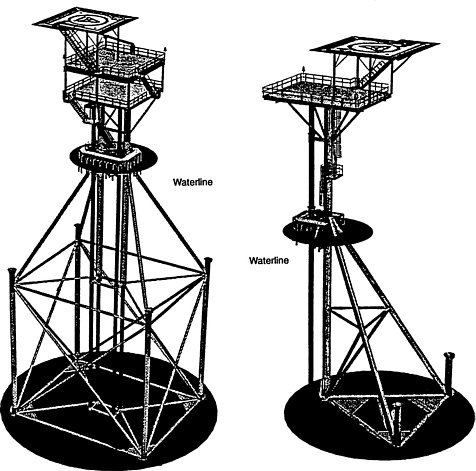

Skirt-Piled Platforms

Skirt-piled platforms have skirt piles driven through sleeves that terminate under water 50 to 100 feet above the seafloor (figure 1-10). This type of platform may also have conventional piling in the jacket legs in addition to skirt piles. Skirt piles may be from 36 inches to 84 inches in diameter. Like some of the minimal platforms described above, the piles are grouted to the sleeves. Skirt piles provide additional axial and lateral load bearing without adding much surface area, which minimizes wave loading. This type of platform is

FIGURE 1-6 Braced caisson with conventional piles (MOSS I). Source: Courtesy of CBS Engineering, Inc.

generally installed in more than 200 feet of water. There are about 150 skirt-piled platforms in the Gulf of Mexico, only 4 percent of the total. However, because they are concentrated in deep water, they will be expensive to remove.

Special Application Platforms

There are several types of special application platforms. For example, around the mouth of the Mississippi River, where the upper layer of sediment is very soft and thick, downslope movement of sediment, or mud slides, can be triggered by hurricanes. Mud slides exert tremendous lateral force on platform pilings. Consequently, pilings and jacket legs of platforms installed in areas subject to mud slides are large (12 feet or more in diameter) and thick (4 to 6 inches). Jacket legs in areas prone to mud slides commonly extend 50 to 75 feet below the mudline, and wells are drilled through the vertical legs of the platform (figure 1-11). There are relatively few of these platforms in the Gulf of Mexico, but removal costs will be very high.

CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT USED IN PLATFORM REMOVALS

In general, platforms are removed in the reverse order of installation: first the deck is removed, then the conductors, the piling, and the jacket. The components of a platform are often large and heavy. Jackets in 100 feet of water can weigh as much as 600 tons and in 300 feet of water more than 2,000 tons (NRC, 1985). Decks can weigh from 100 to more than 3,000 tons. Conductor weight varies with the number and size of casing strings and water depth; conductors usually weigh from 20 tons to more than 150 tons. Soil shear resistance on the pipe, depending on the depth of the cut, can add several tons to removal forces.

Construction equipment used to decommission platforms, plug and abandon (P&A) wells, and remove platforms varies from small lift-boats to large derrick barges. Lift-boats, which are limited to water 100 feet deep or less, are self-propelled, self-elevating vessels with three or four legs connecting a lower mat to the upper hull. The mat is lowered to the seafloor, where it serves as a shallow foundation supporting the upper hull, which is jacked up above the water surface. The hull dimensions are generally 70 feet by 120 feet or less. Lift-boats can house from 10 to 25 people. When outfitted with cranes, lift-boats have a capacity of 10 to 70 tons. They can be used to P&A wells, set cement plugs, and remove production tubing. Lift-boats are not equipped to remove wells with multiple casing strings and are used only to remove very shallow, lightweight platforms.

Derrick barges are large, floating, ocean-going vessels with either ship-shaped or rectangular hulls. Some are self-propelled, but most are towed by tugboats. Although a few derrick barges are dynamically positioned and hold station by means of thrusters, most are anchored at platform sites, with as many as eight drag-embedment anchors and up to a mile of large (1.5 inches to 2.5 inches in diameter) anchor wire per anchor. Derrick barges are equipped with revolving cranes that are built into the hull of the vessel. Crane capacity on a small derrick barge (240 feet by 70 feet) ranges from 150 to 300 tons. Larger hull vessels (350 feet by 100 feet) have crane lift capacities of 600 to 800 tons. A few large derrick barges

FIGURE 1-7 Braced caisson with skirt piles (Seahorse). Source: Courtesy of Atlantia Corporation.

in the Gulf of Mexico have 1,600- to 4,000-ton lift capabilities. (Some vessels based in the North Sea have more than 10,000-ton lift capacities.)

Derrick barges have quarters and support facilities for 50 to 200 people and carry tugs, cargo barges, crew boats, and helicopters as part of the construction equipment. Personnel includes surveyors, divers, welders, riggers, crane operators, mechanics, cooks, and supervisors. The operational people are supported by engineers, estimators, logistics personnel, and others to plan and perform each job as safely and efficiently as possible in the hostile offshore environment.

REGULATIONS, LAWS, AND PERMITS

Since 1953, the U.S. Department of the Interior has managed the development of OCS oil and gas resources. Within the department, the Minerals Management Service (MMS) issues and manages OCS oil and gas leases. Among other responsibilities, MMS ensures that when production ends, sites are abandoned in a manner that minimizes damage to marine life and the environment. MMS ensures that the responsible party plugs abandoned wells to prevent leaks, removes platforms, and clears the lease site of obstructions that might be hazardous to commercial fishers, shrimpers, and other shipping.

The MMS has a comprehensive progam to regulate platform removals. As new issues and concerns arise, the MMS reviews existing regulations and issues revised regulations or notices-to-lessees with additional requirements or procedures. Two examples of this revision process are the U.S. Department of Commerce's National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) Observer Program and the Site Clearance Verification Program. The former provides a 48-hour observation period to ensure that there are no sea turtles or marine mammals in the vicinity of a platform before it is removed. The latter program requires that the area be trawled with a special net after a platform is removed to ensure that there is no remaining debris. The MMS has also been active in developing and promoting the Safety and Environmental Management Program concept with operators and contractors to improve the safety and environmental aspects of offshore operations and facilities.

FIGURE 1-8 Conventional 4-pile platform with wells. Source: Courtesy of Pinnacle Engineering.

Federal Laws and Regulations

A number of laws and regulations that apply to the removal of offshore platforms are summarized in this section. A detailed description of applicable laws appears in appendix D.

Outer Continental Shelf Lands Acts

The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA) requires the secretary of the interior to administer mineral leasing, exploration, and development on the OCS. Objectives of OCSLA include balancing the development of resources with protection of the environment and encouraging the development of new and improved technology that will eliminate or minimize damage to the environment. OCSLA also mandates that the secretary of the interior require the use of the best available and safest technologies.

National Environmental Policy Act of 1969

Under the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA), all federal agencies, including MMS, are mandated to promote efforts to reduce damage to the environment. Under NEPA, agencies must study alternative courses of action when a recommended action might have significant adverse effects on the environment.

Endangered Species Act

The Endangered Species Act requires, among other things, that federal agencies consult with the secretaries of commerce and the interior to ensure that no action taken to remove OCS platforms jeopardizes any endangered or threatened marine species. For example, the NMFS (Commerce) and MMS (Interior) formally agreed on measures for protecting endangered sea turtles in the Gulf of Mexico when oil and gas structures are removed using explosives.

Marine Mammals Protection Act

The Marine Mammal Protection Act prohibits the “taking” of marine mammals except as approved under the act by the secretary of commerce. The term “taking” means “to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.” “Harassment” is defined as “an intentional or negligent act or omission that creates the likelihood of injury to wildlife by annoying it to such an extent as to significantly disrupt normal behavior patterns that include, but are not limited to breeding, feeding, or sheltering.”

“Harm” is defined as “an act that actually kills or injures wildlife. Such an act may include significant habitat modification or degradation where it actually kills or injures wildlife by significantly impairing essential behavioral patterns, including breeding, feeding, or sheltering.” MMS also addresses the effects of abandoning OCS leases on marine mammals in environmental impact statements and environmental studies.

Other Laws and Regulations

Other federal laws and regulations that affect platform removal operations include the Magnuson Fisheries Conservation and Management Act, the Clean Water Act, the National Fishing Enhancement Act, U.S. Coast Guard regulations, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration regulations. State laws include the Louisiana Artificial Reef Initiative Act and the Texas Artificial Reef Act.

Platform Removal Permit Process

The permit process for removal of an offshore platform in federal OCS waters requires the following steps:

-

The operator submits an application with the appropriate form and information to the MMS (the same form is used for explosive and nonexplosive platform removals). Prior to submitting this form, the operator must

FIGURE 1-10 Examples of skirt-piled platforms. Source: Courtesy of Shell Offshore, Inc.

-

have already properly abandoned the well(s) per applicable MMS regulations.

-

MMS consults with NMFS and the Marine Mammal Commission to ascertain compliance with the Endangered Species Act, Section 7, and the Marine Mammal Protection Act and to identify protective mitigation measures and monitoring requirements for the permit. If the removal plan involves the use of explosives, but less than 50 pounds per charge, a generic Incidental Take Statement is prepared. If explosives involve a single charge of more than 50 pounds, the applicant, in consultation with NMFS, must submit a detailed Incidental Take Statement.

-

When the platform removal is scheduled, the operator notifies the MMS district office prior to commencing removal operations. If explosives will be used, NMFS observers are notified to go offshore. NMFS observers must be on site for 48 hours prior to the use of explosives.

-

After platform removal, the operator performs the final site clearance operations, which include removal of obstructions on the seafloor and verification by trawling in depths of up to 300 feet. In depths of more than 300 feet, the operator must verify site clearance by a means approved by the MMS.

-

The operator submits a completion report to the MMS detailing the removal operation and certifying that the site has been cleared.

Rigs-to-Reef Program

If the operator elects to participate in a state rigs-to-reef program, either by placing the structure at an approved reef site or by leaving it in place (after obtaining MMS approvals to remove the platform), application must be made through the appropriate state agency:

-

In Louisiana, the operator submits an application to the U.S. Department of Wildlife and Fisheries; in Texas, to the Texas Department of Parks and Wildlife.

-

The appropriate state agency applies for a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers permit. The Corps has jurisdiction over the explosive removal of the structures (they do not have purview over nonexplosive removals). The operator informs the Corps whenever a platform removal is planned, and the Corps then takes the following course of action: (1) if the removal is in inland state waters, the Corps reviews the application and recommends approval for the removal but sends the

FIGURE 1-11 Mud-slide-type platform. Source: Courtesy of Chevron U.S.A., Inc.

-

application to the NMFS for final approval; (2) if explosive removal is planned and the structure is in open waters, the Corps informs the NMFS and asks if NMFS observers will witness the platform removal. The NMFS then decides whether to implement the observer program and informs the Corps, which in turn notifies the operator.

-

If the platform is to be left on the lease site, the operator must obtain from the MMS a waiver from the lease abandonment regulations, including site clearance requirements.

International Laws

International laws relevant to the removal of offshore structures include the Convention on the Continental Shelf and the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, which require that abandoned or unused installations be removed. International Maritime Organization guidelines also call for the removal of abandoned offshore structures. There is no definition of the depth of removal, except that the structure should be “entirely removed” and not interfere with navigation. Exceptions are granted to coastal nations for reusing structures if they deem it beneficial.

REFERENCES

MMS (Minerals Management Service), Offshore Data Services. 1994. Gulf of Mexico Platforms Installed–1947 to Present. New Orleans: U.S. Department of the Interior.

MMS, Offshore Data Services. 1995. Gulf of Mexico Field Development Report 9:1 (January 30). New Orleans: U.S. Department of the Interior.

NRC (National Research Council). 1985. Disposal of Offshore Platforms. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.