coordination among nations and scientific disciplines; (c) multidisciplinary research on the links between global climate change and human health; (d) improved environmental health training for health professionals; and (e) an outreach program to inform and educate the public about the effects of global climate change on human health. In the face of current fiscal constraints, these efforts must be based on identifying and linking together existing activities, facilities, organizations, and funding agencies.

BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW

In October 1994, following a meeting with concerned scientists and medical experts (Eric Chivian, Bob Shope, and Mary Wilson), Vice President Gore asked the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) and the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) to organize a conference on the potential human health risks posed by global climate change, and strategies to address them—such as global health surveillance, public outreach, and education. Members of the NSTC, OSTP and CEQ formed a working group to develop a preliminary agenda for the conference and later requested that the IOM join in planning, organizing, and conducting the conference. (Appendix A presents a list of the sponsoring agencies, the IOM steering committee, and conference organizing staff.)

The purpose of the conference was twofold:

-

To bring together a diverse, interdisciplinary group of experts to address the potential effects of global climate change and ozone depletion on the current and future incidence of disease, heat stress, food and water supplies, and air pollution; and

-

To discuss initial strategies for improving research and development (R&D), global health surveillance systems, health care and disease prevention, medical and public health community education, international cooperation, and public outreach.

It is important to note that the focus of the conference was human health. Presenting evidence of whether or not global climate change is, has, or will occur, was not the primary focus. Participants were asked rather to work within an “if/then” type of scientific exercise: If global climate change occurs, what are the potential adverse human health effects and what strategies should be developed to address them?

The first day of the two-day conference was filled with scientific presentations and a plenary discussion on the current state of knowledge about global climate change and its potential risks for human health (see the agenda, Appendix B), including a presentation by Vice President Gore (see Box 1). On the second day, participants discussed health policy implications and potential intervention strategies in a series of panels. Each panel's findings were presented and discussed by the conference participants in a final plenary session. Approximately 300 scientists, health care providers, policymakers, academicians, federal and state officials, industry representatives, and others attended the conference and participated in developing the strategies (see Appendix C).

|

BOX 1. The Interplay of Climate Change, Ozone Depletion, and Human Health * Albert Gore, Jr. Vice President of the United States I've spoken before about the radical changes that have occurred in our environment just in my lifetime. As is often the case, when a fundamental change takes place, one can't point to a single causal factor to explain it. In this case, I've come to believe that this radical change in the relationship between civilization and the Earth has come about because of the confluence of three factors at the same time, the first being the population explosion, which is now adding the equivalent of one China's worth of people every 10 years. The second change is the scientific and technological revolution, which has dramatically magnified the average impact that each of the billions of people on Earth can potentially have on the Earth 's environment. And the third factor, the most subtle in some ways but the most important in other ways, . . . there has been a change in thinking about our duty to consider the future consequences of our present actions and a sometimes willful assertion that we can 't possibly have any meaningful impact on the Earth's environment, therefore we shouldn't think about it much less worry about it or study it in detail. Together, these three elements have combined to produce what some of you would call a discontinuity: a fundamental change in the relationship between human civilization and the earth. There is a scientific consensus on the most salient issues, a revisionist few not withstanding: We know that human activities are causing the atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases to increase dramatically in the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide has increased nearly 30 percent since the industrial revolution, methane has more than doubled, and nitrous oxide has gone up by 15 percent. We also know that the current trends are leading to an even more rapid accumulation of greenhouse gases and that, as this trend continues, the concentration of greenhouse gases will continue to mount. Now, in addition to the greenhouse gases, human activities have increased the atmospheric concentrations of sulfate aerosols—the key ingredient in acid rain—especially over industrialized areas in the Northern Hemisphere. In just the last century, the Earth's temperature has risen by about 0.5°C, or 1°F. The nine warmest years this century have all occurred since 1980. There are plenty of other measures—from the tree-ring record to the record in land-based glaciers—that all demonstrate that the current period is by far the hottest that we have been able to measure. And the evidence is getting ever stronger that this warming now under way is not due to natural variability, but to human activities. The real question is: “What will happen in the future?” Without climate change policies that limit global emissions of greenhouse gases, there is no doubt that the Earth's climate will change. It 's not a question of will it change, it is a question of when, by how much, and where. The question of when is now being answered. It has already begun to change significantly. And the best evidence is consistent with a prediction that, in the lifetimes of people now living, we will commit the world to an increase of up to 3° and 4°C—up to 8°F. The scientists warn us that change is coming. |

*Excerpts from remarks at the Conference on Human Health and Global Climate Change, September 11, 1995.

|

How will global warming affect us? There are clearly profound implications at the regional level for food security, water supplies, natural ecosystems, loss of land due to sea level rise, and human health. A temperature increase of 2° to 8°F is projected to double heat-related deaths in New York City and triple the number of deaths in Chicago, Los Angeles, and Montreal. And an increase of 8°F may be correlated with an increase in the heat/humidity index of 12° to 15°F. The very young, the elderly, and the poor will be the ones most at risk. So will those with chronic cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. The past summer's stunning number of deaths in Chicago—over 500 in just a few days—make these hypotheses all too real. Changing temperatures and rainfall patterns are predicted to also increase the spread of infectious diseases. Insects that carry disease organisms may now move to areas that were once too cold for them to survive. These new breeding sites and higher temperatures may also speed reproduction. Diseases we had hoped were just a memory in this country are suddenly a renewed threat. Cholera is resurgent in our hemisphere. After years of being contained in much of the world, Dengue Fever has returned to countries that had not seen the disease in 50 years. Malaria, too, is a global concern, and some of the new strains are more troubling than any that have been seen. Malaria already infects several hundred million people each year —mainly in the Tropics. But this July, for the first time in 40 years, more than 100 people contracted malaria in a Russian city. And besides the return of old diseases, there are new ones on the U.S. scene, such as the hantavirus in the Southwest. Unfortunately, ignoring the news does not make it better. Closing your eyes to a problem doesn't make it vanish. You can't simply wish ozone holes away. So it astounds me, in light of all the data that has been collected over the years, that some are once again challenging the fact that there is ozone depletion. And what's even more amazing is that some people are listening. Ladies and gentlemen, we have an extraordinary international consensus: We have thousands and thousands of atmospheric measurements linking manmade CFCs to global ozone depletion. We all know that depletion of the ozone layer increases the amount of UV-B radiation that reaches the Earth. And so now we have to confront the fact that the observed depletion of ozone of 5–10 percent in summertime, when people are outdoors a lot, will increase nonmelanoma skin cancer in fair-skinned populations by about 10–20 percent. In addition, there will be an increase in the incidence of cataracts and other eye lesions, and cataracts are already the third-largest cause of preventable blindness in the United States. These numbers would be much higher yet were it not for the success of the Montreal Protocol. We must not forget though, that even with that world-wide action, it will be until the middle of the next century before the ozone layer recovers. Well, for the past 25 years, the United States has been committed to the bipartisan effort to protect the environment. . . . President Clinton has . . . fought to make sure that the United States is at the forefront of a global environmental movement. We're striving to return greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by the year 2000. We're striving to convince others to make as much progress as is possible. We're engaged in international negotiations to address this global problem. We're helping to develop treaties not only for the protection of our own nation, but for the health and welfare of the world community of which we are a part. We know that science is essential to our understanding of global problems. Ladies and gentlemen, the role of the scientific community in articulating clearly the best accepted understanding of what we know and what we can say with sufficient confidence to enable the American people to take prudent measures to safeguard our future is absolutely critical. |

Greenhouse Warming

Without the naturally occurring “greenhouse effect,” Earth would be too cold to sustain life as we know it. The greenhouse effect results from water vapor, carbon dioxide, and other trace gases in the atmosphere that trap solar heat as it is reradiated from the Earth's surface. The net effect is to keep the planet about 33°C (60°F) warmer than it would be otherwise. In the past century, however, human activities have added substantially to this effect by releasing additional greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, primarily through combustion of fossil fuels. Carbon dioxide concentrations have increased nearly 30 percent, nitrous oxide about 15 percent, and methane approximately 100 percent. The principal source of the emissions that produce the atmospheric concentrations has been the burning of fossil fuels (coal, oil, and gas), although agriculture and deforestation contribute a share.

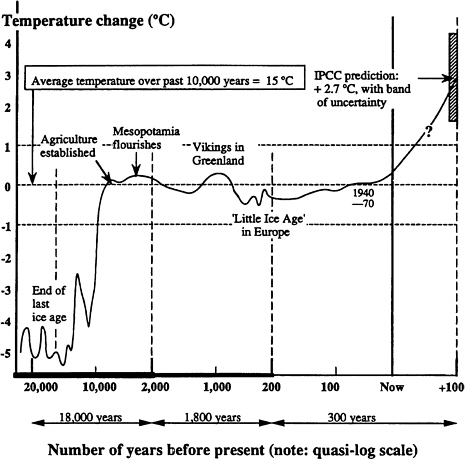

There is a growing consensus in the scientific community that the increase in greenhouse gases has contributed to a warming of the earth's surface by between 0.3° and 0.6°C (0.5° and 1.1°F), on average, over the past 100 years (see Figure 1). In some regions, particularly in the industrialized areas of the Northern Hemisphere, this warming has been masked by increased concentrations of air pollutants such as sulfate aerosols, which reflect solar radiation (and thus serve to counter-balance, in part, the warming that might be seen otherwise). Nevertheless, the nine warmest years in this century have occurred since 1980, and there is considerable evidence to support this warming trend (see “References and Further Reading, ” p. 28): decreases in Northern Hemisphere snow cover and Arctic sea ice, the retreat of glaciers in all of the world's mountain ranges, and a measurable rise in average sea level—10 to 25 centimeters (4 to 10 inches) over the past 100 years—mainly due to thermal expansion of water.

While emissions of greenhouse gases will certainly continue in the future, the exact amounts will depend on population growth, economic development, energy technologies, and policy variables. Nevertheless, according to the participants, it seems reasonable to expect that global emissions of carbon dioxide will rise in the short term from the current level of approximately 6 billion tons of carbon per year, to between 8 billion and 15 billion tons per year in 2025, and could range from 5 billion to 36 billion tons per year by 2100. This would mean that atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide—which were 200 parts per million (ppm) during the last ice age and about 280 ppm in preindustrial times—could rise from today's 350 ppm to anywhere from 500 to 900 ppm by 2100.

The scientific community has growing confidence in the ability of computerized general circulation models to predict the climate impacts of such changes in greenhouse gases. These models, which provide an increasingly good fit between theory and observation of past global climate changes, indicate that, in a world with approximately twice the current concentration of carbon dioxide, the global mean temperature will increase by 1° to 4°C (2° to 7°F), with significant regional variations (e.g., somewhat less warming in the Northern Hemisphere due to air pollution). Average evaporation will also increase, and hence average precipitation, again with regional variations (more rain in some places, especially in winter, less rain in others, especially in summer). Sea level will rise by another 15 to 90 centimeters (6 to 35 inches) over the next 100 years.

Participants noted that the impact of such changes on natural and human systems will be mixed. Increased carbon dioxide concentrations would have a “fertilizer” effect for some plants, but not for others, leading to changes in natural plant communities and ripple effects on animal species. Overall, the balance would probably be tilted in favor of “weedy” species—those with higher rates of reproduction and dispersal—to the detriment of biological diversity. Tropical forest communities will be affected, and there will probably be some die-off in boreal forests as well. Temperature-related changes in the oceans will affect the world's coral reefs and ocean fisheries. Global agricultural production may be unchanged, although increased production in northern latitudes might be offset by decreases in tropical regions where many populations are already malnourished. Coastal populations may be dislocated by changes in sea level, and there will likely be increased numbers of other “ecological refugees” as well.

Ozone Depletion

A thin layer of ozone high in the atmosphere (the stratosphere) protects life on earth, shielding the surface by absorbing much of the ultraviolet radiation from the sun. However, surface ozone (in the lower atmosphere or troposhpere) is a major component of urban smog and can also serve as a

FIGURE 1. Variations in average global temperature over the past 20,000 years and predictions for the next century. (McMichael, 1993)