6

Effective Communication with Families and the Community

Helping providers improve their delivery of immunization services is critical, but making sure that families receive and act on the message that they should seek immunization for their children also must be a concern. A variety of methods are needed to communicate with families, and the messages they receive must be meaningful to them. This concern is not new or unique to immunization. A variety of analytical tools such as the Health Belief Model (e.g., Rosenstock et al., 1959; Rosenstock et al., 1988) have been developed to help investigators understand what combination of knowledge and circumstances leads to a positive health action, such as having a child immunized. The model stresses the need for a parent to believe that his or her child is susceptible to one or more serious diseases that are preventable by effective and safe immunizations and that those immunizations can be obtained conveniently and inexpensively.

KNOWLEDGE AND ATTITUDES

An initial concern is whether families know about immunization. Although some families lack the most basic information about immunizations, most do know that they should immunize their children. Reports at the workshop on studies for CDC in Rochester, New York, and in inner-city areas of Philadelphia and Los Angeles showed that a large majority of families have some knowledge about the value of immunizations in preventing illness.

Many families, however, have difficulty keeping track of the immunization schedule or what vaccines their children have received. Lance Rodewald

reported at the workshop that 61 percent of parents in a Rochester, New York, study could not remember when their children needed immunizations, and 81 percent of the parents of underimmunized children thought that their children had received all scheduled vaccine doses.

Families also may not know that children with mild illnesses can be safely immunized. A study of families using Salt Lake City's immunization clinics found that 45 percent had delayed bringing a child in for immunization because the child was ill (Abbotts and Osborn, 1993). The authors concluded that most of those illnesses were not true contraindications to immunization.

Workshop participants suggested that, in some families, meeting the health care needs of well children may be given a lower priority than providing day-to-day necessities such as food and shelter. Providers encounter parents who have not taken the time to have their children immunized until school or day-care requirements prompt action. In his pediatrics practice, James Feist has found that even physicians ' children may not be immunized as recommended. The failure of many insurance plans to cover immunizations also may suggest that they (and other excluded preventive care measures) are not truly important.

Other parents are concerned about the safety of vaccines or object to immunization because it introduces substances into the body that parents perceive to be unnatural. Tracy Lieu noted that parental concerns about vaccine safety are not necessarily a deterrent to immunization; among families in the Northern California Kaiser Permanente HMO, children with parents worried about the safety of vaccines were less likely than other children to receive their immunizations late, suggesting a general parental concern for their children's health.

Unanticipated findings such as Lieu's suggest that “conventional wisdom” about parental attitudes should be tested to ensure that planning for immunization programs is based on accurate assumptions. Lance Rodewald and David Salisbury both noted that providers thought that parents would object to the simultaneous administration of multiple vaccines. When asked, parents were, in fact, willing to have all appropriate immunizations given at one visit.

Immunization programs are using a variety of incentives, penalties, and legal requirements to encourage families to have their children immunized. The scale of the positive or negative stimulus can affect the character of the response (e.g., Bandura, 1986; Fiske and Taylor, 1991). Large incentives or penalties can become so important in themselves that they deflect attention from their original purpose—encouraging immunization to protect a child's health, for example. Laws requiring immunization for school entry succeed in their immediate purpose but do not promote the message that children should be immunized at much younger ages or the intrinsic value of protecting one's child from preventable illness. In general, small incentives remain cues to take a particular action and do not become the main motive for action. All parents

who take a positive health action, for whatever reason, should receive credit for protecting their children against serious illness.

EDUCATING FAMILIES AND THE COMMUNITY

Workshop participants agreed on the need across the country for more and better efforts to educate families about the importance and safety of immunization and to encourage them to have their children immunized appropriately. The messages need to be delivered to individual families and to the community as a whole, and the messengers need to include individual providers, office and clinic staff, community groups, and public health officials.

The committee emphasized that this national public education campaign must be sustainable and sustained, in contrast to many of the valuable but short-term and highly focused efforts that developed in response to the measles epidemic. Immunization education for families and the community must become a continuing activity to reach a steady succession of families with newborn children and to reinforce the message that families must take repeated actions to have their children fully immunized.

Education and outreach programs must emphasize the value of immunizations and the importance of having very young children receive all the recommended immunizations at the recommended times. Families need to understand that their unimmunized infant or toddler is at risk of catching serious but preventable diseases. The community as a whole needs to be aware that its unimmunized preschool children increase the risk that children and adults who are not fully immune to these diseases will become ill. The emphasis in years past on up-to-date immunization for school entry seems to have overwhelmed the newer message that children need to receive most of their immunizations by the time they are 2 years old. For example, a study in Puerto Rico found that most of the immunization posters displayed in health clinics emphasized immunization requirements for school entry and identified special clinics providing those immunizations (Gindler et al., 1993).

Resources for Public Education

David Salisbury stressed how valuable the United Kingdom had found professional market research in guiding the public information elements of its immunization program. “Selling” immunization to the public is given the same thorough analysis and development given to selling commercial products. Salisbury showed three 30-second television spots to illustrate the messages and the recurring elements that tie all immunization program advertisements together. The British also have used the introduction of new vaccines as an opportunity

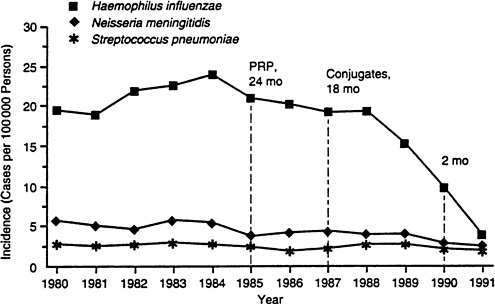

to revitalize their message to the public about the importance of all immunizations. The committee thought that much more could be done in the United States to publicize the success of vaccines in reducing serious illness. The dramatic decline in Haemophilus influenzae meningitis following the introduction of Hib vaccines provides an excellent opportunity to publicize a recent success (see box).

Anthony Robbins noted that the NVPO has begun working with professional advertising agencies to develop outreach materials for the President 's Childhood Immunization Initiative. Plans to promote greater awareness of the importance of immunization call for highly visible activities at the national level. NVPO also will be working with state and local groups to encourage the development of community coalitions and public-private partnerships that can participate in immunization education programs. Federal agencies such as the Cooperative Extension Service of the Department of Agriculture, which has offices in every county and a long history of community education, are participating in these activities. Independent efforts already under way, such as the National Immunization Campaign and the Every Child By Two campaign for early immunization and its Immunization Partnership project with the American Nurses Association, have brought a diverse array of companies, professional and civic groups, and advocacy organizations into immunization education activities.

States and communities will need to draw on the particular resources available to them and formulate programs that can reach their populations effectively. For example, David Smith observed that Dairy Queen ice cream stores, the one constant throughout rural Texas, have joined in the state's immunization education program. Public service announcements can be delivered by print (e.g., billboards and newspaper advertisements) and broadcast (radio and television) media. Carmen Paris, a health educator and Special Assistant for Community Relations in the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, underscored the importance of community outreach and education on immunization, and on health care services more generally. Limited funding for community outreach activities in a recent Philadelphia grant for immunization tracking led Paris to emphasize the need for adequate support for these activities.

Role of Health Care Providers

Health care providers and their staffs are well-placed to educate families about immunization and should be prepared to do so. Parents generally view them as an authoritative source of guidance on child care. Optimally, children should be seen in their medical home by providers who are familiar to the family and who have access to a child's medical history. Even when children are seen in a variety of settings, each provider can reinforce the immunization message.

Families may have more contact with office staff than with physicians or nurses and may find them more approachable. That gives office staff important opportunities to help educate families about immunization. Appointment

opportunities to help educate families about immunization. Appointment scheduling, for example, is an excellent opportunity to remind families when children need immunizations.

Workshop discussions also pointed to other approaches. Some clinics and special programs assign case managers or use visiting nurses to work with families. In the United Kingdom, community nurses visit families at home soon after the birth of a child to confirm the child 's enrollment in a computer registry. They also visit when children have not received scheduled immunizations. Immunization messages in the United States can be communicated through programs such as AFDC, Head Start, or WIC. Housing, job training, and counseling programs also can be used.

Christopher Koepke, from the Albert Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia, reported that his colleague Susan McCombie found that the introduction of immunization screening in Philadelphia WIC offices was associated with an improvement in immunization rates. Among children whose WIC participation ended before screening began, only 29 percent were up to date on their immunizations. After screening was introduced, 49 percent of children currently participating and 37 percent of former participants were up to date. Although the proportion of children whose immunizations were up to date remained far below the desired level, the improvement with screening was valuable.

Reaching the Community

Informing the whole community about the importance of immunization can help create an environment that encourages families to use the available immunization services. In some local health departments, official immunization representatives on the staff work with community groups. Within the community, influential leaders of organizations such as churches and civic groups can deliver positive messages about immunization that help overcome families' apprehensions and correct misinformation they may have received. At the neighborhood level, respected individuals able to communicate with families on a personal basis can provide information about immunizations and immunization services as well as encourage the use of those services. Immunization education will benefit from strong support from within the community to overcome distrust of government officials and programs or of messages received from outside the community.

Jeffrey Goldhaggen emphasized that the Cleveland All Kids Count project created a registry and tracking system not only as a tool to improve immunization rates but also as a way to link children to providers and strengthen the primary care system as a whole. Because the system relies on Touch-Tone telephone and fax communications, it is easily used by providers and families. The voice-mailbox given to every family creates a direct link to the health care

system as well as a personal communication resource. Appointment information and other messages from providers are transmitted through the voice-mailbox by calls the communication system places to a family 's home. Families without telephones must call their voice-mailboxes to receive appointment information, but the opportunity to receive messages from family and friends (as well as health care providers) gives them an incentive to use the system.

Cultural Appropriateness

Culturally appropriate messages and materials are an essential part of information and education programs. They must take into account not only the language generally spoken in the community, but also the community's beliefs and attitudes regarding immunization, health care, and the providers in the area. Magda Peck noted that one California community found that giving families vouchers for immunizations overcame their reluctance to accept free immunization services.

Similarly, outreach and follow-up activities must be culturally appropriate. Automated dialing devices, for example, can be programmed to deliver appointment reminders and follow-up messages in specific languages. Steven Black pointed out, however, that Kaiser Permanente and many other providers may need to add information such as a family's preferred language to their records to be able to deliver customized messages. Kaiser is beginning to use Spanish-language materials but has not yet developed materials in the several Asian languages spoken by their members. Some materials for Spanish-speaking populations may also be more effective if they are adapted for specific groups (e.g., Cubans, Mexicans, or Puerto Ricans).

RISK COMMUNICATION

The committee found that risk communication is a special concern. Although vaccines provide enormous benefit, they also carry small risks of adverse reactions (IOM, 1991, 1994a). In 1986, federal legislation mandated the development of materials—Vaccine Information Pamphlets (VIPs)—to inform children's families about possible adverse reactions to vaccines. Amendments to the legislation in 1993 call for revisions to the VIPs as a result of widespread concern that they had become one of the barriers to immunizing children. New VIPs are under development.

The pamphlets must be distributed at every immunization visit and may reinforce existing concerns about vaccine safety or create new ones. In their current form, the VIPs do not adequately balance the risks against the benefits of immunization. Generally, providers do not have ready access to quantified

estimates of disease risks that families can compare with the quantified risks associated with the vaccines that are described in the VIPs. 1

The committee agreed that families' fears and the small but real risks of adverse reactions to vaccines must be acknowledged, but that more needs to be done to communicate the benefits of immunization. James Feist suggested that providers such as himself who must use the VIPs should have a greater role in developing them. Providers also may benefit from a better understanding of the formal principles and techniques developed by risk communication specialists.

IMPROVING COMMUNICATION WITH FAMILIES AND THE COMMUNITY

Steps to Take in the Short Term

-

Importance of immunization by 2 years of age. Providers, public health officials, and the many others who have a role in immunization education need to deliver a clear message that children must have most of their immunizations before they are 2 years old. They need to counter the impression that requirements for full immunization for school entry mean that children do not need to be immunized until then.

-

Education by providers and office staff. All members of the health care system need to be able to educate families about their children's immunization requirements. Physicians and nurses are important sources of information and should be able to provide detailed guidance about vaccines and immunization schedules. Other office and clinic staff also provide important information to families and need to be informed contributors to immunization education efforts. They can help keep parents aware of their children 's immunization schedules and endorse the value of immunization for keeping children healthy. Understanding the values and culture of the families being served contributes to successful communication and education. Development of a lay version of CDC's

1

Providers' perceptions of how families view the VIPs need to be validated. A study published after the workshop was held found that 76 percent of the parents who received the pamphlets said that the information encouraged them to have their children immunized (Clayton et al., 1994). By comparison, only 38 percent of the parents whose children were immunized before the VIPs were introduced gave a similar response regarding the information they received. The study does not provide a complete picture, however. Because it included only parents whose children received immunizations, it does not reflect the views of any parents who may have chosen not to have their children immunized.

- Standards for Pediatric Immunization Practices (CDC, 1993b) might produce a valuable educational resource for families and providers.

-

Information on new vaccines and immunization schedules. Immunization education can help prepare the public and health professionals for impending changes in available vaccines and in the immunization schedule by informing them about the new vaccines and the new versions of existing vaccines that are under development. As new products are licensed, changes are likely to occur in the number of immunizations a child receives and when they are given. Families also may find that more providers disagree about which recommended immunizations are essential. Because the differences in providers' views may make it harder for families to know whether their children have received all the immunizations they need, better immunization education for families will be especially helpful.

-

Information about vaccine successes. The public health community can make a greater effort to inform the public about vaccine successes. The rapid reduction in meningitis produced by use of the Hib vaccine is a good starting point. Information about the effectiveness of a vaccine against a disease that many families have seen and know is a serious threat to a child can help balance apprehensions about the risks that may be associated with vaccines. Because vaccines have been so successful, families may never have observed how serious the diseases they prevent can be.

-

Presentation of risks and benefits. CDC can work with providers, professional organizations, state and local public health departments, and representatives of the public to revise the Vaccine Information Pamphlets so that they present a more balanced picture that weighs the benefits of a vaccine against the risks it may pose. The United Kingdom does not use quantitative estimates of vaccine risks in materials for families, but they may be necessary for materials distributed in the United States.

-

Vaccine Information Pamphlets. CDC needs to revise the Vaccine Information Pamphlets so that they are easier for families to read. Part of making them easier to read may include making them shorter.

Steps to Take in the Longer Term

-

Risk communication skills and resources. Providers, community educators, and health departments need better risk communication skills and resources to respond to concerns about the potential dangers of immunization. In particular, Vaccine Information Pamphlets should reflect the principles of risk communication.