1

Introduction

OIL POLLUTION ACT OF 1990

Following the grounding of the Exxon Valdez in March 1989 when more than 11 million gallons of crude oil spilled into Prince William Sound in Alaska, Congress moved quickly to pass the Oil Pollution Act (OPA 90) in August 1990. Two goals of OPA 90 were to reduce the occurrence of future oil spills through preventive measures, such as improved tanker design and operational changes, and to reduce the impact of future oil spills through heightened preparedness. The act calls for far-reaching efforts to reduce oil pollution by mandating major changes in the way tank vessels transport oil in U.S. waters and by specifying which vessels can carry oil. For the first time, Congress effectively recognized that although vessel casualties1 cannot be prevented entirely, improvements in the design and operation of oil-transporting vessels can minimize the amount of oil spilled in the event of a casualty. OPA 90 addressed a number of areas of concern, including oil pollution liability and compensation, spill response planning, and international oil pollution prevention and removal.

Other preventive measures addressed are alcohol and drug abuse, licensing and registry, manning standards, vessel traffic services, the periodic gauging of the plating thickness of commercial vessels, overfill and tank monitoring devices, pilotage, and the establishment of double-hull requirements for tank vessels.

|

1 |

The definition of casualty in the context of this report refers to incidents such as groundings, collisions, allisions, or structural failure, in which the vessel is damaged. It should be noted that a casualty may or may not result in an oil spill, depending on the extent and the location of the damage. Also, vessel casualty and vessel accident may be used interchangeably in this report. |

Because parts of the act would have a dramatic impact and could result in significant changes in the economics and structure of the industry, Congress required a review after five years of implementation of the last requirement of the act, “establishing double hull requirement for tank vessels ” (Section 4115).2 The review would assess the effects of operational and structural changes on the safety of the marine environment and on the economic viability and operational makeup of the maritime oil transportation industry. Thus, the goal of the current study is to review the preventive measures mandated by Section 4115 and to ascertain their effect on pollution prevention, safety, economics, and the composition of the marine petroleum transportation industry in U.S. waters.

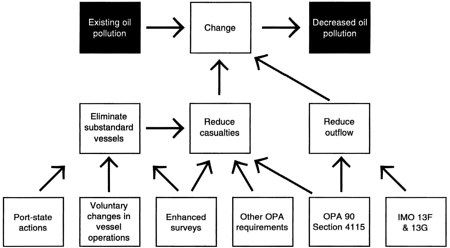

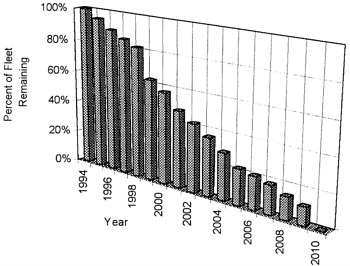

Preventive measures are spelled out in Section 4115 of the act. Although these measures constitute only a portion of the OPA 90 requirements, as shown in figure 1-1, they mandate fundamental changes in the design characteristics of vessels that transport oil in U.S. waters. The act mandates the replacement of preOPA 90 single-hull tankers that call at U.S. ports with double-hull tankers, according to a prescribed phase-out schedule. In addition, Section 4115 requires that the U.S. Coast Guard develop regulations pertaining to structural and operational measures to reduce the outflow of oil from existing single-hull tankers until these vessels are retired. The rationale behind this mandate is the presumption that double-hull tanker designs and significant changes in the structure and operational procedures of existing single-hull tankers will reduce the risk of oil spills from tanker casualties or will minimize the amount of oil spilled from such casualties. The effect of the phase-out schedule on the world fleet of single-hull vessels is shown in figure 1-2, which indicates the number of single-hull vessels remaining at the end of each year. This estimated percentage is based on the size and the age of existing tankers and on the schedule specified in OPA 90 for phasing out single hulls of various sizes and ages.

The effect of this phaseout on oil pollution depends on the effectiveness of the double-hull design in preventing the flow of oil following a casualty. In a 1991 NRC study on double-hull tankers, a committee concluded that double-hull vessels would reduce the outflow of oil in the event of a casualty, resulting in fewer or less severe oil spills than single-hull tankers (NRC, 1991). Expected reductions in oil pollution would then follow the pattern shown in figure 1-2, and the amount of oil pollution would be reduced in proportion to the percentage of single-hull vessels retired.

In addition to the construction and operational impacts of OPA 90, the tanker industry was forced to reevaluate the manner in which it carries oil, in light of the strict liability provisions for oil spills and the increased costs of operation in case of accidental oil spills. These increased costs come at a time when both the market

|

2 |

Although Section 4115 of the act is entitled “establishing double hull requirements for tank vessels,” it also establishes requirements for developing interim measures for the single-hull fleet until all these vessels have been phased out under the mandates of the section. |

FIGURE 1-1 Relationship of Section 4115 to the Oil Pollution Act of 1990.

for tankers and oil shipping rates are emerging from a depressed period when income was often insufficient to cover the costs of operation and capital investment. Section 4115 of OPA 90 adds to the economic variables of the maritime oil transportation industry by mandating changes in the configuration of vessels the industry uses to transport oil. The costs associated with these changes will have to be borne by the industry in terms of higher expenses and, perhaps, by the public in terms of higher prices for oil products.

A number of difficulties in assessing changes in the marine petroleum transportation system have emerged as a result of OPA 90. First, the effects of Section 4115 are only beginning to be felt in the market because the first mandated

FIGURE 1-2 Percent of remaining world tanker fleet tonnage based on OPA 90 single-hull tank vessel phase-out schedule. Note: Exceptions for lightering and deepwater ports will extend the trading life of single-hull vessels to 2015. Data include accidents involving tank ships and tank barges. Compiled using data from Clarkson Research, Ltd. (1995)

retirements took place in 1995 and tankers constructed after the promulgation of OPA 90 are just entering service. Second, other parts of OPA 90, such as increased liability provisions and the potentially high cost of oil spills, have combined to force internal changes in the way vessel owners and operators run their vessels to lessen the risk of vessel casualties. Changes in the international regulatory environment, enhanced surveys, the increased vetting of vessels by charterers, and increasing port state control activities are also affecting the safety of ships carrying oil. Finally, the act may affect the number of vessels calling on U.S. ports because of new operational requirements, such as hydrostatic loading and increased under-keel clearance, as well as changes in lightering patterns resulting from double-hull exemptions. These factors affect the safety of the overall fleet, either by preventing casualties that could result in oil spills or by decreasing the number of vessels subject to casualties. Figure 1-3 depicts the interrelationships of the various factors affecting the safety of the oil transportation system. The influence of Section 4115 on safety improvement is clearly intertwined with other factors; thus, the effects are difficult to isolate. The significance of major factors is discussed below.

FACTORS AFFECTING SHIP SAFETY AND POLLUTION PREVENTION

International Regulatory Regime

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) regulates international shipping through adoption by its members of a number of conventions, including the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as amended by the Protocol of 1978 (MARPOL 73/78) and the International Convention on Safety of Life at Sea, 1974 (SOLAS 74).

In November 1990, the United States submitted a proposal to the 30th session of the IMO Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC30) to establish an international requirement for double-hull tankers. This proposal eventually resulted in the adoption of Regulation 13F of Annex I of MARPOL 73/78 on March 6, 1992.

Regulation 13F specifies hull configuration requirements for new tankers contracted on or after July 6, 1993, of 600 DWT 3 capacity or more. Oil tankers between 600 DWT and 5,000 DWT must be fitted with double bottoms (or double sides), and the capacity of each cargo tank is specifically restricted. Every oil tanker of more than 5,000 DWT is required to have a double hull (double bottom and double sides) or the equivalent. These requirements are compared with those of OPA 90 in table 1-1.

The IMO regulation specifies that other designs may be accepted as alternatives to double hulls, provided they give at least the same level of protection against oil pollution in the event of collision or grounding and they are approved, in principle, by the MEPC, based on guidelines developed by the IMO. The guidelines employ a probabilistic methodology for calculating oil outflow and a “pollution prevention index” to assess the equivalency of alternative designs.

In addition, IMO Regulation 13G addresses existing single-hull vessels in the world fleet. This regulation applies to crude oil tankers of 20,000 DWT and above and oil product carriers of 30,000 DWT and above and specifies a schedule for retrofitting (with double hulls or equivalent measures) or retiring existing single-hull tank vessels 25 or 30 years after delivery. The differences between the Regulation 13G and the OPA 90 schedules are shown in table 1-2.

Tankers not fitted with segregated ballast tanks (SBT)4 or fitted with SBTs that are not protectively located (PL) must designate protectively located double-side (DS) or double-bottom (DB) tanks or spaces upon reaching 25 years of age. In appropriate locations, SBTs would be acceptable as protectively located spaces. Regulation 13G also acc epts hydrostatic loading5 and other alternatives (operational or structural) to protectively located spaces. Tankers built in compliance with Regulation 1 (2G) of MARPOL 73/78 have protectively located ballast spaces and require no modifications until reaching 30 years of age. Upon reaching 30 years of age, all tankers must convert to double hulls.

|

3 |

Deadweight tons (DWT) is a measure of the cargo capacity of a ship. |

|

4 |

Segregated ballast tanks (SBTs) are tanks designated for ballast only. |

TABLE 1-1 Comparison of Requirements of OPA 90 and IMO Regulation 13F for New Vessels

|

Size |

Hull requirements |

Enforcement date |

|

|

OPA 90 Section 4115 |

<5,000 GTa |

Double containment systems |

Building contract placed after June 30, 1990 Delivered after January 1, 1994 |

|

>5,000 GT |

Double hull |

Building contract placed after June 30, 1990 Delivered after January 1, 1994 |

|

|

IMO Regulation 13F |

<600 DWT |

Not applicable |

|

|

600–5,000 DWT |

Double hull or double sides |

Building contract placed after July 6, 1993 New construction or major renovation begun on or after January 6, 1994 Delivered after July 6, 1996 |

|

|

>5,000 DWT |

Double hull or equivalent |

Building contract placed after July 6, 1993 New construction or major renovation begun on or after January 6, 1994 Delivered after July 6, 1996 |

|

|

aGross Ton (GT) is a measure of the registered tonnage and is not directly related to cargo capacity. |

|||

The United States has reserved its position on the 13G loading and structural provisions applicable to existing single-hull tank vessels and, at the writing of this report, the U.S. government had not issued regulations under OPA 90 for existing vessel structural modifications or hydrostatic balance. Regulation 13G also imposes a program of enhanced inspection during periodic, intermediate, and annual surveys for all subject vessels.

The impact of these international regulations will be analyzed by the committee in conjunction with Section 4115 of OPA 90.

|

5 |

Hydrostatic loading means that the level of cargo (e.g., crude oil) is limited to assure that the hydrostatic pressure at the tank (and ship) bottom is less than the external sea pressure at that point. Thus, if the tank is breached, sea water flows in. |

TABLE 1-2 Comparison of Requirements of OPA 90 and IMO Regulation 13G for Existing Vessels

|

Size |

Hull requirements |

Enforcement date |

|

|

OPA 90 Section 4115 |

<5,000 GT |

Double containment systems |

After January 1, 2015 |

|

>5,000 GT |

Double hull |

Per schedule starting in 1995 |

|

|

>5,000 GT |

Structural operational and structural measures |

No date set |

|

|

IMO Regulation 13G |

Crude carriers >20,000 DWT |

Double hull or equivalent |

30 years after date of delivery |

|

Product carriers >30,000 DWT |

|||

|

PL/DS or PL/DB or PL/SBT or hydrostatic balance loading or equivalent |

25 years after date of delivery |

||

|

Code: PL/DS–protectively located tanks, double side PL/DB–protectively located tanks, double bottom PL/SBT–protectively located tanks, segregated ballast tanks |

|||

Other Domestic and International Actions

Port state inspection programs, enhanced surveys by classification societies, and increased vetting6 by charterers are the three major initiatives that have been undertaken since the adoption of OPA 90. Because the OPA 90 provisions concerning single-hull tank vessels under consideration in this report have not yet been implemented, and double-hull requirements have only recently been incorporated in new construction, consideration of these inspection and survey developments may elucidate the changes in spill patterns since the passage of OPA 90.

Port State Effects on Ship Safety

Port state control efforts have increased substantially in the past few years. Historically, port states (nations that have vessels calling at their ports) have not exercised substantial control over vessels that use their ports, delegating the responsibility to flag states (nations in which vessels are registered) to ensure that

|

6 |

Vetting is the quality assessment review of the history of a particular vessel conducted by a charterer prior to entering into a chartering agreement. |

vessels meet all levels of soundness. Traditionally, this role has been left to vessel owners, flag states, and ship classification societies. Because of a concern that substandard vessels are still operating and that a growing number of vessel owners are registering ships in nations that do not meet their flag-state obligations, the IMO, regional organizations, and individual nations have taken action to increase port state control.

In 1994 more than 40,000 port state control inspections were conducted in Europe, Scandinavia, Canada, Australia, South America, and the United States. Currently, three regional Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) have been signed to coordinate port state programs: the Paris MOU (1982), the Tokyo MOU (1993), and the Acuerdo de Viña del Mar (1992). (See table 1-3.)

The IMO recently adopted port state control regulations that include criteria for qualifications and a code of conduct for port state control officers.7 Compliance with the International Safety Management Code (ISMC) and revisions to the Convention for Standards for Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping (STCW) will become additional points of review for port state control programs.

In the United States, the U.S. Coast Guard has adopted a more aggressive posture as a port state. Like Australia, which published a list of the “Ships of Shame,” the United States is targeting vessels for port state surveillance and is making that information available to the public. A key feature of the regional MOUs and the U.S. and Australian programs is the sharing of information among port states.

Enhanced Ship Surveys and Increased Vetting by Charterers

Enhanced surveys of vessels have been mandated by IMO Regulation 13G. The surveys, which take place every five years, require increasingly strict inspections as vessels age. The program is intended to prevent the operation of substandard ships that could cause oil spills due to structural failure. The more prominent classification societies (members of the International Association of Classification Societies) have begun aggressive programs to ensure that vessels under their classification meet or exceed present requirements.

Major charterers have developed sophisticated vetting programs, including vessel inspections, flagging patterns, and ownership and management qualification requirements, prior to chartering vessels. An indirect result of the adoption of OPA 90 has been the increased emphasis on safety in these programs.

This report, representing the first phase of a two-phase effort to review the implementation of Section 4115 of the act, evaluates the sufficiency of available data for analyzing changes resulting or expected from implementation of OPA 90

|

7 |

IMO Resolution A. 787 (19), Procedures for Port State Control, adopted at the 19th session of the assembly, November 23, 1995. |

(Section 4115). This report represents the judgment of the committee regarding the availability and adequacy of data for answering the following questions:

TABLE 1-3 Main Features of Regional Port State Control Agreements

|

Agreement |

Paris MOU |

Acuerdo de Viña del Mar |

Tokyo MOU |

|

Authorities that adhere to the MOU |

Canada, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom |

Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Uruguay |

Australia, Canada, China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Papua New Zealand, Russian Federation, Singapore, Vanuatu |

|

Authorities that have signed but have not yet accepted the agreement |

Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Venezuela |

Fiji, Philippines, Solomon Islands, Thailand, Vietnam |

|

|

Cooperating authorities |

Croatia, Japan, Russian Federation, United States |

||

|

Observer authority |

United States |

||

|

Target inspection rate |

25% annual inspection rate per country within 3 years from effective date |

15% annual inspection rate per country within 3 years from effective date |

25% annual regional inspection rate by the year 2000 |

|

Governing body |

Port State Control Committee |

Port State Control Committee |

Port State Control Committee |

|

Secretariat |

provided by the Netherlands Ministry of Transport and Public Works (Rijswijk) |

provided by Prefectura Naval Argentina (Buenos Aires) |

Tokyo MOU Secretariat (Tokyo) |

|

Database center |

Centre administratif des affaires maritime (CAAM) (Saint-Malo) |

Centro de informacion del acuerdo latinamerico (CIALA) (Buenos Aires) |

Asia-Pacific Computerized Information System (APCIS) (Ottawa) |

|

Official language |

English, French |

Spanish, Portuguese |

English |

|

Signed |

January 26, 1982 |

November 5, 1992 |

December 2, 1993 |

|

Effective date |

July 1, 1982 |

November 5, 1982 |

April 4, 1994 |

-

Has Section 4115 of the act been effective in reducing the amount of oil pollution entering U.S. waters from tank vessel casualties?

-

Have the provisions of Section 4115 of the act had an effect on the economic condition of the maritime oil transportation industry operating in U.S. waters and, if so, to what extent?

-

Have the provisions of Section 4115 of the act changed the operational makeup of the industry transporting oil in U.S. waters (i.e., who carries oil in what kind of vessels and to which ports)?

-

What changes have occurred in the design and construction of double-hull tank vessels as they become the required design, rather than the exception? What are the implications for the safety of maritime oil transportation?

The report also identifies gaps in available data and methods for closing them. In areas or cases where gaps cannot be filled, the report assesses the consequences of insufficient information on the committee's ability to review the implementation of OPA 90, Section 4115.