Lessons from HealthPASS and Oxford Health Plans

David Snow, Jr.

Managed care is a subject for which I have a tremendous passion and I apologize up front for any biases I may bring to the table, because I truly believe that managed health care is an outstanding vehicle for the delivery of care to vulnerable populations if the health plans are set up properly.

Although the topic tonight is managed care and all vulnerable populations, I am going to focus specifically on Medicaid recipients as a type of vulnerable population. I think the things we talk about here can also be applied to Medicare, but since I have a 15-minute time restriction, I will limit my comments to Medicaid and I will try to give you an overview. I hope that through the question and answer session later, we can go into greater detail.

I have organized my presentation into three key components. First, I am going to talk a little bit about my experiences operating a Medicaid managed care program in two urban settings, Philadelphia and New York City. Again, take my comments for what they are worth. They are oriented toward urban settings. Ask someone else about the application of Medicaid managed care programs in rural settings. That is not where my experience lies.

Next, I will outline for you some of the lessons I have learned from my Medicaid managed care experience over the past six years.

Then, in closing, I will describe some of my concerns about health care reform as it is envisioned under Clinton's proposal. While the reform plan does not specifically deal with vulnerable populations at this time, there are important issues on the table for public policymakers as they grapple with alternative approaches. It is my hope that through such discussion we can avoid some serious pitfalls that could reverse the improvements to date in how we deliver health care to vulnerable populations.

The Philadelphia HealthPASS Program, for those of you who are not aware of it, is an 82,000-member health insuring organization that is exempt through grandfather clause from the federal 75/25 rule. * HealthPASS serves Medicaid recipients only. HealthPASS has had a controversial history, mostly because it was one of the pioneers in the early eighties, taking aggressive action to move Medicaid recipients out of the traditional fee-for-service Medicaid system into a managed care environment. Many political and operational mistakes were made in the early eighties. However, today I consider the HealthPASS Program to be one of this nation's state-of-the-art programs.

HealthPASS is a mandatory Medicaid managed care program in south and west Philadelphia. Traditional fee-for-service does not exist for Medicaid patients in the HealthPASS demonstration area. There are approximately 110,000 Medicaid recipients in the demonstration area, and there are three health plan options that a Medicaid recipient can choose: two commercial HMOs and the HealthPASS Program, which is a state-owned program managed by a private contractor.

The HealthPASS Program is also the default HMO, meaning that if a Medicaid recipient does not voluntarily choose one of the two HMOs, they are automatically placed into the HealthPASS Program. The private contractor for the HealthPASS Program (which was Healthcare Management Alternatives or HMA when I was there) is at full risk.

For those of you who have a preconceived notion that managed care is only successful if it skims the healthy population for membership, I should tell you that HealthPASS, because it was the default HMO, could not skim membership. By the way, I do not believe that HMOs

|

* The 75/25 rule is a federal statute that states that any federally qualified HMO serving Medicaid patients must have at least a 25 percent private pay enrollment. |

skim the population either, but by definition, HealthPASS took all comers. HMA's Medicaid membership composition was 53 percent AFDC recipients, 8 percent SSI/aged, 14 percent SSI/disabled-blind, and 25 percent general assistance.

As most of you know, when you enroll beyond the AFDC population, which is the healthiest of the four categories, you are enrolling sicker, far more vulnerable individuals. For example, within the general assistance population, HMA had 5,000 homeless individuals under their care.

In New York City, my experience is a little different. I currently work for a company called Oxford Health Plans. Oxford is a commercial HMO with Medicare and Medicaid lines of business that were added within the past two years. Oxford currently has 255,000 members, of which 20,000 are Medicaid. Oxford has set up its Medicaid line of business as a totally separate and distinct cost center. That is extremely important if one is really going to make a difference when serving Medicaid recipients and if one is really going to be accountable.

In New York, Oxford currently markets to Medicaid recipients in Brooklyn in two distinct program environments. Certain zip codes in Brooklyn are included in a state- and city-sponsored mandatory enrollment demonstration program. The remaining zip codes in Brooklyn are voluntary enrollment zones, where Oxford must hire sales representatives and aggressively go out and market. One spends a lot more money in a voluntary marketing environment.

I personally think the mandatory approach is much more sensible; however, politically it is a very difficult thing to get approved by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) at this point in time, what with the waivers and other requirements. Again, Oxford in New York is at full risk for serving the enrolled Medicaid population.

In Philadelphia, HMA was paid 86 percent of fee-for-service to operate the program. That is because it was a mature program and had been operating for more than eight years. Both New York and Philadelphia implemented Medicaid managed care programs for five specific reasons:

-

Rapidly increasing health care costs,

-

Limited and decreasing access to services,

-

Incentives for inefficiency,

-

No focus on preventive care, and

-

Worsening health status of recipients.

As regards lack of access, New York City Medicaid recipients could not get care from private practitioners anywhere because fee schedules had deteriorated so badly that an office visit was reimbursed at $12 and yet it cost the physicians more than $12 to collect the fee. As a result, recipients had to go to Medicaid mills, hospital emergency rooms, or hospital clinics, if they could go anyplace at all. Lack of access to preventive care drives costs upward owing to increased need for acute interventions later in the disease process.

Tremendous incentives for inefficiency do exist in the fee-for-service Medicaid programs in most big cities. There is absolutely no focus on preventive care and, despite increasing expenditures in the Medicaid program, the health status of the population has been deteriorating in the fee-for-service programs. Tuberculosis is getting worse. AIDS is on the rise. Infant mortality is increasing, not decreasing. Pennsylvania and New York City felt it was very important, not only for cost efficiency but also for reasons of quality and access, to give Medicaid managed health care a chance.

It is my personal opinion that all of the Medicaid managed care models out there today are better alternatives than the traditional fee-for-service system, across the board. States throughout the country are implementing various models of Medicaid managed care with outstanding results. In contrast to the fee-for-service system, with managed care one is able to:

-

Foster more cost-efficient health care delivery,

-

Increase access to appropriate services and ensure access to care,

-

Foster continuity of care,

-

Better control the costs of care without reducing benefits to Medicaid recipients, and

-

Better assure that high-quality care is provided.

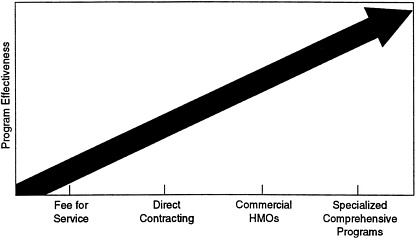

FIGURE 1 The continuum of Medicaid managed care solutions.

Having said that, I wish to point out that certain managed care models are better than others. There is really a continuum of managed care models. Let's look at Figure 1. As we travel out on the horizontal line, we see various types of managed care programs, starting from fee-for-service programs, which in this graph are the least cost-effective, moving to direct contracting, or the primary care case management model (e.g., KenPAC), continuing out to commercial HMOs, which manage the Medicaid population within the framework of their commercial population. Then farthest out on the line of effective managed care models is the specialized comprehensive program, whether it be a Medicaid-only managed care program or a commercial HMO that has isolated the Medicaid line of business and whose employees focus on the unique needs of the Medicaid population, giving them as much attention as others give their commercial population.

I have consulted with a number of HMOs that merge Medicaid and commercial populations together in the same model, thinking that the needs of both populations are the same. Typically, the results have been disastrous. At best, they have been far less effective than health plans that tailor their programs to the unique needs of vulnerable populations.

The best practices, the ones that are furthest out on that line, tailor their programs to meet the needs of Medicaid recipients. First of all, they are sensitive to the fact that there are all sorts of barriers, beyond the financial, that prevent Medicaid recipients from accessing care. Language is a big barrier that most fee-for-service programs do not deal with. Twenty-four hour, seven-day-a week translation service and multilingual staff for big-volume populations is critical. Materials printed in the appropriate language are absolutely essential. In addition, education levels are a barrier. Commercial HMOs that do not know the literacy levels of Medicaid recipients often hand out the commercial population literature to their Medicaid recipients, not recognizing or acknowledging that the material should be written at a third or fourth grade reading level if the material is to hit home. We have convened many focus groups on this and we learned that you completely miss your audience if you do not recognize their reading levels and cultural issues.

One must recognize that, for generations, Medicaid recipients have used emergency rooms to access care. Basically, they have been persona non grata in the private health care system. We must make specific efforts to prove private care is available by performing outreach, pulling individuals into the system, so that they know they are welcome in settings other than emergency rooms and Medicaid mills. We must eliminate Medicaid mills so they are not even an option. The whole educational process is absolutely key to eliminating barriers. One must invest money up front to change behavior and get people to be comfortable with the system.

Infrastructure is always a problem in the inner cities. There are not enough practices where the largest densities of Medicaid recipients live. So, even though you increase fee schedules and you improve the environment for physicians to practice, you often do not have enough physicians to meet the total demand that occurs when all of the Medicaid recipients are moved into a private managed care system. The best practices go out and seed practices in areas of need. They invest money in infrastructure. They purchase practices. They do what they have to do in order to make care available in the communities in which Medicaid recipients live. And that does not happen unless the health plan achieves critical mass, meaning at least 20,000 to 30,000 Medicaid recipients within the program.

Transportation is another barrier. One must pay for transportation if the health plan wants the recipient to treat preventive health care as a priority.

Lack of a social service orientation can diminish a health plan's effectiveness and create barriers to care. Social service activities are absolutely mandatory to serve Medicaid populations. For a Medicaid population, health care is not the top priority. Often, concern about having a roof over one's head, heating one's house, or putting food on the table for one's kids are priorities that make vaccinations and checkups seem unimportant. The only way to elevate consciousness regarding health status is to deal with some of these other high-priority items. So, effective managed care programs that link with community agencies and fund programs that deal with these traditionally non-health-care issues are the ones that ultimately save health care dollars, and in addition successfully elevate the quality of life and the health status of the vulnerable population they are serving.

Programs I have been involved with have been very aggressive in the area of community outreach and health education. We cannot just pay physicians more and make them accessible and expect Medicaid recipients to change their lifestyles and patterns of behavior. We must physically identify vulnerable populations within a Medicaid program and pull them into the system.

Some of the best practices of Medicaid managed care are as follows:

-

Eliminate barriers to access, including:

-

language barriers,

-

educational barriers,

-

cultural barriers,

-

habitual access patterns,

-

infrastructure, and

-

transportation problems.

-

-

Provide a social service (non-health-care) component.

-

Provide extensive, tailored health education and community outreach, including:

-

an infant mortality initiative,

-

a lay home visitors program,

-

school-based health centers,

-

an immunization initiative, and

-

an asthma initiative.

-

-

Provide specially trained member service representatives who will be available 24 hours a day.

-

Tailor quality assurance programs.

-

Tailor case management programs.

-

Apply extensive fraud and abuse prevention technology.

-

Act as a community catalyst.

A focused initiative, for example, includes the whole area of infant mortality. All women who are pregnant are identified and programs that bring them to an obstetrician in the first trimester are developed. In Philadelphia, we funded what we called the Lay Home Visitors Program, which basically was similar to the barefoot doctor concept in China, where physicians and nurses trained lay people. These lay people were culturally part of the community, were trusted, and could overcome the many barriers listed earlier. They would identify pregnant individuals in the program, so that they could be counseled about nutrition and about the importance of prenatal care in the first trimester. The lay people could also identify high-risk lifestyles and high-risk medical problems that should be addressed immediately.

If I were to go into many of the communities I serve, I would not be trusted. I would not be listened to. In many cases, I would not be understood. You must identify and train people who are trusted within the community. A Lay Home Visitors Program is very expensive. A health plan cannot do it when it has a base of only 5,000 members, but as Medicaid managed care programs get larger, it is amazing what creative activities are going on out there in the country. Also amazing is the willingness of the private sector to invest in the health care

infrastructure of poor communities. These things are not feasible in the fee-for-service system.

Another example of outreach initiatives we funded was the development of school-based health centers. In a middle school in Philadelphia 80 percent of the students were members of the HealthPASS Program. We saw tremendously high levels of teen pregnancy, substance abuse, and learning deficits as a result of violence in the community, unstable family structures, and other problems that made it very difficult for students to learn. This investment in school-based health will bring tremendous positive results to the west Philadelphia community.

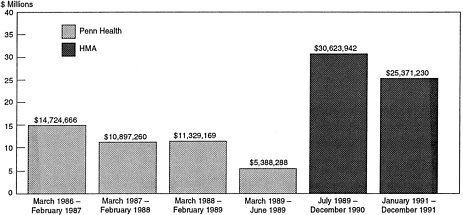

Figure 2 shows savings under Maxicare's management and HMA's management of the HealthPASS Program. These are savings to the state and federal government only. The sources of savings came from the following areas:

-

Earlier intervention,

-

Reduced emergency room utilization,

-

Reduced pharmaceutical fraud and abuse,

-

Use of appropriate alternative settings, and

-

Reduced inpatient days.

Table 1. Fee-for-Service Versus Managed Care, Observed Patient Days per Thousand

|

Payer Category |

Fee-for-Service |

Managed Care |

|

Commercial Medicaid |

495 |

360 |

|

AFDC |

1,020 |

580 |

|

Medically Needy |

6,200 |

3,400 |

|

SSI |

5,400 |

2,800 |

|

HealthPASS |

2,600 |

1,500 |

Table 1 shows that patient days per thousand are cut by half under a managed care structure. This is not so because care is being denied. It is so because we are actively intervening early in the health care process (preventively), so that those acute, expensive beds are not needed later in the disease process.

A few final comments on President Clinton's reform plan and its impact on vulnerable populations are important. We all know that one of the thoughts is to integrate Medicaid recipients into health alliances. It is a great idea in that the Medicaid stigma will be removed across the country and physician payments would be improved across the country. Also this plan would eliminate many of the problems related to loss of Medicaid eligibility.

However, I want to put several concerns on the table. If you cannot identify a Medicaid recipient, if you do not know out of the thousands of people in your system who is poor, it is very hard to tailor a program to meet the unique needs of vulnerable populations. We have already seen that Medicaid recipient health outcomes are not optimized when the recipients are treated as commercial enrollees. I am concerned that the best practices outlined earlier in this talk will be impossible to implement in a massive health alliance environment. Another concern is whether these massive health alliances will be able to determine who is serving vulnerable populations well and whether they will be able to measure performance in this area. If you do not know who a Medicaid recipient is, it is going to be hard to hold plans accountable for the populations they serve.

A final concern is that a massive push for national reform could actually stall the Medicaid managed care revolution taking place at the state level while we wait for federal initiatives to be implemented. Federal action may have some positives, but I think that hands-on knowledge is crucial. We should not lose ground and forget what we have learned over the past ten years when we move to some kind of federally-legislated plan.

Lessons from Medica in Minnesota

Lois Wattman

My interest in health law evolved through my medical assistance work in the Minnesota State Senate in the early 1980s. I had graduated from law school and did not find an area of the law that interested me until I got into the medical assistance field. From that interest has evolved 10 to 12 years of working in health care generally. But as we look at reform and as I look at health law, I must say that Medicaid is my passion. So, I am absolutely delighted to be able to talk to you about how vulnerable populations are going to fare under health care reform.

I was struck by the topic for this presentation: striking the right balance between access and efficiency. The topic implies a need to pit access against efficiency and I do not think that is necessary. Managed care, for example, may be a more efficient form of health care delivery, but it also can bring improved coordination of services, additional services, special programs, and enhanced access. Access and efficiency need not be mutually exclusive.

Let me describe Medica because we are a plan that differs somewhat from the plan that you heard described by David Snow. Medica is a large, nonprofit health maintenance organization with over 550,000 enrollees and revenues in excess of $1 billion annually. We have 90,000 Medicare members and 47,000 medical assistance enrollees. We are an independent practice association (IPA) model HMO, and have

close to 5,000 physicians. If a physician wants access to our 500,000 enrollees that are not on medical assistance, they also have to see our medical assistance enrollees. We require all of our providers to see our medical assistance populations. We are located primarily in the metropolitan Twin Cities area, although we have some offices in other counties throughout the state of Minnesota.

In this presentation I would like to discuss three topics: Medicaid managed care in Minnesota, Medica's evolutionary involvement in that program, and what an organization like Medica views as major concerns in looking at health care reform and vulnerable populations.

My work in medical assistance started, as I said, in the early 1980s and involved designing the first Medicaid demonstration project. Minnesota was one of the early pioneers in medical assistance managed care, and in the early and mid-1980s we designed a program that was considering enrolling the AFDC population in Medicaid demonstration projects. The kind of controversy that we are seeing today at the national level was exactly the kind of controversy we had ten years ago in Minnesota as we started to put the program together. What people said at the time is echoed in the current debate over health care reform:

-

The special needs of certain populations cannot be met in a managed care environment.

-

The financial incentives in managed care to the underserved are such that needs will not be met.

-

Access to needed mental health and substance abuse programs will not be adequately met in a managed care environment.

-

Integration with the public health system and other important social services will not occur in a Medicaid managed care model.

Now, either those of us who were designing the program at the time were very naive, or else society has changed a lot since the eighties, but we started with the fundamental assumption that the AFDC population could be treated as a commercial population. We were wrong. Those of us who are now, ten years later, trying to retrofit a program to meet their needs have just realized how terribly wrong we were. Despite the fundamental error in our assumption, however, the state has continued its commitment to managed care. By 1995, Minnesota will have 50 percent of its Medicaid enrollees in managed care. Currently about 20 percent of the Medicaid population, or 82,000 people, are enrolled. It is

now a mandatory program in two counties. Medica does not actually market for its share of the Medicaid population. The county describes the managed care options that are available to individuals when they enroll in medical assistance.

Medica became involved in managed care for Medicaid recipients in the mid-1980s with the other health plans. We viewed it as part of our mission. Our mission has been to be the leader in improving the quality, affordability, and accessibility of health care, and not simply for easy-to-serve populations. We are currently involved in two counties: Hennepin, the largest county in Minnesota (where Minneapolis is located), and Dakota, a suburban county just south of Minneapolis. In 1989, we had 12,000 medical assistance enrollees and as of today, we have 47,000. They comprise 9 percent of Medica's membership and 12 percent of our revenue. Of the 47,000 enrollees, 5,000 are elderly and the rest are on AFDC.

When I arrived at Medica a couple of years ago, the Medicaid and Medicare programs were part of our product line. We had the Medicaid product and the Medicare product, but it was not working. What problems were we encountering? First, we had some difficulty because of our large provider network. That meant that we attracted large numbers of enrollees. Approximately 65 percent of all the Medicaid recipients in Hennepin County were enrolled in our plan and the providers were not amused. They were very unhappy. Further, at the time we had no special ability to take care of that population. Second, our administrative systems were unresponsive to the needs of a medical assistance population with respect to billing and enrollment. We have to be flexible. We have to be able to do retroactive determinations and deal with enrollees whose eligibility turns off and on over short periods of time. That is not the kind of billing and administrative system that a normal commercial HMO has. Third, we absolutely lacked the ability to handle populations who did not speak English or who did not have a middle-class understanding of either the health care system or managed care, and who often had very special access needs. Fourth, as an organization, we lacked an understanding of the public health system and the local social services networks and the interactions between those two. Finally, we lacked a connection with the communities of which these members were a part.

We knew something was wrong. The community was telling us. The advocates were telling us. The providers were saying, “You better

fix this, Medica.” So, what did we do? Well, as large corporations often do when they have a problem, we formed a task force. We had three meetings in our offices out in the suburbs overlooking a beautiful wooded area. We sat on the tenth floor and after about the third meeting, we looked at each other and said, “How dare we? Who are we to sit here in a lofty environment and talk about what is wrong with our medical assistance population and medical assistance programs?”

So, we came up with what I think was a novel idea, at least for us. We said that we needed to go out and ask the medical assistance members what they would like, what they need out of a program. With that began a journey and for those of us who worked on it, a very loving journey.

We commissioned a study. It was a six-month study involving over 2,000 people who were asked to respond to mail, phone, or personal interviews. Not only did we ask these people to respond, we asked them to help design the survey. And in designing the survey and in the survey process, we probably learned more about the needs of the population than from the survey results.

Let me give an example. As you know, ear infections are very common among children. In most cases it is easily treated with a medication—pink stuff—that needs to be refrigerated. Well, people were showing up in the emergency room because they did not have refrigerators to keep the pink stuff in. So, we thought of a good survey question: “Do you have a refrigerator?” You know what response we got from the community? You can't ask, “Do you have a refrigerator?” You have to ask, “Do you have a refrigerator where you live that will keep the medicine cool?” Think about it. That one question has three elements that are critical when you deal with underserved populations: “Do you have a refrigerator? Is it located where you live? And does it work?” Now, if we have to take a simple question like that and break it into multiple components, we have an idea of how complicated it may be to explain managed care. We learned so much about how to communicate and work with the population by having to struggle through the basic questions that we wanted to ask in our survey.

Not surprisingly, we learned in our survey that most of the barriers to health care had nothing to do with health care, but were, in fact, related to nonmedical issues such as transportation, language, daycare, and other social needs. We also learned that the responses and the needs of the population varied significantly by cultural subgroups.

When we talk about the medical assistance population, we are not talking about one population. We are talking about multiple populations that use the system and access the system very differently.

For example, there is a large population of Southeast Asian immigrants in the metropolitan Twin Cities area. A large number of them are Hmong and come from a region in Laos. The Hmong view health care very differently. Their society is run by elders and they have a shaman, who is a spiritual leader. The Hmong view pediatric immunizations as letting the spirit out of their child. Obviously, this presents a real challenge. Here we have parents who are trying to protect their children by not getting immunizations.

Another particularly telling survey result related to emergency room use. We learned that, yes, the medical assistance population uses the emergency room at basically the same rate as our commercial population. But then we asked, “Have you ever been hospitalized after you have been in the emergency room?” Straight across all the population subgroups—Native American, Russian, Vietnamese—about 20-23 percent were saying yes, which is close to the percentage for our commercial groups. However, among the Hmong population, 75 percent were admitted to the hospital, which says something about how they use the health care system. They avoid it until the point at which they are forced to enter the system, and then they enter it at a higher cost and at much greater risk to themselves.

We have to deal with each population according to their culture or orientation. At Medica we have implemented a series of programs with the goal of allowing medical assistance recipients to be like the middle class when they use the health care system. When they need services, we make sure they have transportation. Translation assistance is available and we are working on daycare. We try to remove the kind of discrimination that may occur because of social and economic barriers. Currently our multilingual staff has embarked on its own cultural diversity training.

I would like to mention a special program called the Pathways Asthma Program. It was designed specifically for our medical assistance enrollees, for whom the leading cause of missed school days and the fourth most common reason for emergency room visits was asthma. We initiated a series of home visits, but the real thrill came last summer when Medica funded 39 medical assistance kids for a ten-day camp stay, staffed by health care professionals who helped them learn how to control

their asthma. We are now doing a study to see whether that intervention has had any effect on the utilization of health care resources.

What are some future challenges? We have to figure out how better to work with the public health system, more clearly defining the major responsibilities of all parties, and, more importantly, determining where and how responsibilities should be shared as more emphasis is placed on population-based health. We also need to more effectively work with community organizations and focus on community issues that are not related to health care.

In closing, I would like to mention two of my concerns about health care reform. First, to not recognize the difference in providing health care services to vulnerable populations is to ignore reality. If we cannot identify and respect the special needs of these populations, we will not be able to meet those needs.

Second, funds must be available to meet special needs. If, for example, the medical assistance recipients say that the primary barriers to access within the system are not medical but, in fact, involve social factors, transportation, language, and daycare, we must figure out a way to finance those services. We should not continue to keep the social system and the medical model system isolated from each other.

A Perspective from Academic Medicine

Thomas L. Delbanco

Tonight I am going to wear my doctor's hat, which I have been doing more and more recently. I find it is probably the most relaxing and most rewarding part of my week. With my doctor's hat on, I will try to make three points to you, and make them as graphically as possible.

The first point is that the nice thing about health care reform apparently is that once you announce that it is going to happen, it does happen. Therefore, you have an opportunity to study it as it happens so that you can plan for it when it formally happens. The second point is that much of the health care reform rhetoric depends on a technology that I think is still in the Model T stage of development and this scares the hell out of me. I will give you an example of that. The third point is that if you think there have been perverse incentives before, just watch what might happen if we are not careful.

To make these points, I am going to talk about an Ethiopian patient, a man who just had a heart transplant, and a sulky young sophomore from Boston University, all of whom I saw for the first time last week. I will also talk about another patient, a patient who is probably dying on the wards right now and is making me feel very guilty for being here today. They illustrate some of the points I am going to make.

There is a tremendous upheaval going on right now in the issue of who takes care of whom, as you know. I have been enlarging my panel of patients in the past six months, and I have seen about 60 new patients. I would say that 90 percent came to me for primary care because someone told them to do so because of changes in their insurance status.

Let me get back to the three patients I saw last Wednesday afternoon. One was a young Ethiopian man who couldn't speak a word of English but came with a translator. He was delighted to have a doctor in America, but he represents all the cultural challenges that Lois Wattman alluded to earlier. I think he is depressed. I think the depression he has is manifested by headache, which started when he went to Somalia suddenly seven years ago and has not gone away since. But I have no idea how to treat depression in Ethiopians, and I am going to have to learn quickly how to do it.

The second patient is a patient who actually has 14 doctors. He is the husband of someone who works in our hospital. The reason he has 14 doctors is that he has a new heart that was given to him by an institution exactly a hundred yards away from us that we don't talk about anymore, since it merged with another institution a little further away. The reason he needs me as a primary care doctor is that the insurance company told him he has to have a primary care doctor and his wife's coverage doesn't cover anyone in that neighboring institution because they only do tertiary and quaternary care. So, my job with him will be to write as many letters as possible to his other doctors to authorize him to go on seeing them.

The last patient was a sulky young woman from Boston University, who was sent over by a health service nurse because she, too, needed a primary care physician, although she was quite sure what she needed was a surgeon right away because her right upper quadrant was hurting a lot. Indeed, she was right. She had gallbladder troubles, she should probably have gone to a surgeon first before she saw me, and she was furious that she had to come through me.

On the other hand, I am thrilled at the notion, as a primary care doctor, that continuity of care and my role as a coordinator, the role that Joel Alpert clearly defined for us twenty years ago, is really going to happen. Although this is stimulated by external pressures, I want to take full advantage of it. But I am afraid there could be problems.

This brings me to the “Model T” technology and that thing called capitation. I don't know how much capitation is actually going to happen. I don't know how inextricably intertwined with managed care, or managed competition, capitation will prove to be. If we are really close to depending on it happening, we are in big trouble. The reason is that, while the phrase rolls off the lips with a great sound, we just don't know how to do “managed care.”

The Health Security Act, the plan that has been promulgated by President Clinton, says that the proposed health alliances, or whatever form the large payers will adopt, will pay “a fixed premium for each individual or family that enrolls, adjusting the total payments to plans to reflect the health status of that plan's participants.” That is what health alliances are giving to each enrollee: a fixed premium. And the size of the premium will be risk adjusted according to each individual's projected needs.

The trouble is we don't have a clue about how to do that. We don't have a clue how to predict, unless you have enormous populations, what is going to happen to whom in a given year. And that brings me to Mrs. B, who I think is dying.

Mrs. B has been my patient for 21 years. She was very healthy on January 1, 1993. In April, she came to see me with accelerated hypertension, which came out of the blue. Until then, I was seeing her once a year. Now I had to begin to see her with great frequency. And then followed a cacophony of disaster. Every organ system in her body is failing. To this day we don't know why, and all the best and brightest at our place are trying to figure out what is going on.

Mrs. B has been in and out of the hospital. She is a single mother, living in South Boston, covered by a Medicaid managed care program. She has four kids. When I called one on the phone to talk about his mother, he said, “Doc, I can't talk right now. Give me five minutes. I am just shooting it in. Once it is in, I will feel better, and we can talk about what is happening to my mother.” He is a heroin addict who is having trouble getting into a methadone program and isn't quite sure he wants to. Think about what she costs now, and think about what it is to capitate her now for a year.

How about the diabetic man (new onset) whom I saw for the first time last week? He just left his wife, has a belly that hurts, and is depressed. How much should someone pay me per year to care for that man in a proactive way?

Now, you say, okay, no sweat. The Harvard Community Health Plan is just down the street. They have hundreds of thousands of patients. They will spread risk, and you will take care of a few people who are very sick, but they will be offset by all those people who pay premiums and never show up.

But what about the hospital-based doctor in a small group practice, which is what I happen to be? What about the other doctors in small practices in and around our nation? I am already getting subtle— and not so subtle—messages from my administrative colleagues, those who help to determine what I will bring home and whether my program will be in business at the end of the year. They are suggesting we really have to reach out more and more to those who are not so sick and achieve access for them. Furthermore, are we sure we have to see these very sick people quite as often as we do? Could we not make more room for new patients?

Now, in our practice we take care of 500 people with HIV infection. We think it is important to do so. We have a lot of help at hand and probably can even take cost-effective care of these patients. But the question my administrators pose, as capitation comes along, is this: Will we really get a fair shake for these people? Risk adjustment for ambulatory care is still in an infancy stage.

But given that, look at the problem we have had with diagnostic related groups (DRGs). We have been using them now for many years. They continue to creep, to expand and overlap. They creep inexorably and, in fact, now there is talk about changing them all and starting over.

DRGs look like a piece of cake compared to severity adjustment, or case-mix adjustment for ambulatory patients. The prospect of telling office-based doctors that we can predict the experience they and their patient will have in a given year is a daunting one intellectually. I am worried that we will end up with card-carrying patients who are actually medically homeless. Now, you say, Tom, you are talking about “cream skimming.” You are right. I am. But who has been doing it before? The insurance companies. Those are the bad people. If you work in an insurance company now, you make up for the money you make by slouching around and covering your head and hiding. They are the bad guys. Everyone is dumping on them.

I worry that most of the proposed reforms will transfer to doctors the same perverse incentive to market to the healthy and to avoid the ill:

If I am told, “We will give you money now to care for X number of patients,” I will have a strange set of perverse incentives.

There is a solution. I think you should salary doctors. You can give me modest incentives to enlarge my panel and see more patients, but basically I should be salaried to take care of one and all. We have existing systems that work well.

Let me give you one more example of what I am worried about. If everyone has a health security card granting equal access to care, it will not matter where a provider takes care of people. Right? In fact, providers will even reach out to the underserved. What is my hospital doing right now and what are others doing? They are marching like mad into Lexington, Massachusetts, where I live, and setting up primary care programs in well-heeled communities. I do not see them rushing headlong into Roxbury or Dorchester where the underserved are. I am not saying they are bad people. But they can count, and they are afraid of a capitated reimbursement system. They know the burden of illness that poor people carry. They know it is larger than for those who have been getting care over time and are not poor. They know it is likely over time, if capitation is the linchpin, that they will do better taking care of those who are well and who have resources. So far, they would rather not take care of those who are ill and underserved. Capitation makes them think that way. It may work some day. So far, it is not ready. I do not want doctors to be tempted to turn away from those in need. It is not what we are—or should be—about.

DISCUSSION

JEROME GROSSMAN: Thanks, Tom. You have, indeed, pointed out some important problems.

What we have heard tonight is a very interesting mix of perspectives. There are those who say you can do Medicaid capitated managed care and do it well. Others, like Tom, are worried about the ability to do it effectively within the existing framework. I wonder whether either of our two first speakers have a response to Tom's dilemma.

DAVID SNOW: I think Tom's concerns are well founded. Just as managed care or HMOs have worked out problems and conflicts through slow evolution, so too physicians may be forced headlong into an environment in which they are completely uncomfortable. It has been shown through the Medicare program, looking at the average adjusted per capita cost (AAPCC) methodology, that he is absolutely right. I don't even think we are at the “Model T” stage yet in terms of rate setting and accurately reflecting the risks of a population.

While I think Tom's comments are valid, I do not think they are justification for trying to slow down our current rate of Medicaid managed care evolution because everything I see is a positive evolution. I think that as physicians accept that the environment is changing and start putting some of their creative talent into working to help us further refine the way we do business, we can work through a lot of Tom's concerns. But it means two-way communication and a joint commitment to meeting the needs of the population. It won't happen overnight.

LOIS WATTMAN: We not only function on a capitated basis at Medica with our Medicaid population, we also have 45,000 enrollees in our Medicare program who are also capitated. However, we treat these two groups very differently. In our Medicare population, our physicians are in fact capitated and manage the risks themselves, whereas in the medical assistance program, our physicians are paid on a fee-for-service basis.

So, while we are capitated, the physicians are not. I think that as we start talking about budgets and capitation, we tend to think of capitation at the physician level, which is not necessarily where it has to be. It could be at a much larger level.

As to the concern that was mentioned on the AAPCC: I must say that in Minnesota the concern is that conservative states will be penalized. In fact, the methodology rewards the fatter systems, and those of us who have been conservative through the years struggle with the AAPCC calculations. In terms of a national budget, that is a very real concern for us. In New York and New Jersey, the AAPCCs for 1994 came out and our rates were significantly below theirs. The Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) have been wonderful in the last few months, working with us to put together a demonstration project that looks at some new approaches for how we can deal with these kinds of issues.

But, I agree, our ability to perform the appropriate kind of risk adjustment, as well as to set the appropriate methodologies, is in the early stages, but I do not think we necessarily have to push all the risks onto the provider.

GROSSMAN: Now let us turn to the audience.

COMMENT: I am Joe Newhouse from Harvard. I would like to say I agree with Tom's diagnosis, but I don't think his therapy is efficacious because I think the problem is at the plan level. If the plan is fully capitated, the administrators of the plan can still send signals to salaried physicians that they do want certain kinds of patients or they don't want certain other kinds of patients. In my opinion full capitation probably isn't going to work well. There has to be some mix of capitation and actual reimbursement for services at the plan level.

QUESTION: I wonder whether you could comment on the quality of professional services available to vulnerable populations. We have known for a long time that fewer physicians are available to vulnerable populations and those that do serve the poor are often less trained and less qualified.

Related to that is the question of available treatment settings. We have a long history of institutions of lesser quality being available to indigent populations and other vulnerable populations. So, the combination of quality in providers, hospitals, and related institutions is crucial to our being able to solve this problem.

THOMAS DELBANCO: I think separate but equal has never worked very well in this country. The implicit part of your question is: As long as systems are separate, are you going to get comparable quality? I have been working for more than 20 years to get a one-class system of care for ambulatory patients.

Let me tell you about a remarkable paradox. I am in a fight right now with our secretary of state and our governor. Why? Recently we have received missives from the governor's Medicaid people saying, “We really think you should not take care of poor people anymore in the Beth Israel primary care practice because you are so expensive! ” So, I have closed the clinics and attracted those with means to the same settings that the poor seek out. I build a one-class, first-class system of care for

all—and am told to stop taking care of the poor—those who have the most need!

WATTMAN: A couple of responses. First of all, one of the tenets of our network, as we have defined it, has been that the providers who serve our commercial population also serve our medical assistance populations. We believe this is working well.

So, from a quality standpoint we are not differentiating and from a credentialing standpoint we are not differentiating between how we treat our populations. Our struggle right now is that we are not sure that this is right. We are struggling with this issue from the possibility that our traditional base of providers may not be very well equipped to meet the special needs of these populations. So, we may, in fact, be better off looking at a smaller network of providers that, in fact, have the capability of bringing together the social services, the linguistic services, and the like to meet the needs of the population.

I stated in my presentation that our physician network was ready to explode with the large increase that we had in our medical assistance population. So, we put a cap on it. We went to the county and said we have to cap the number of enrollees we have. We ended up penalizing the providers who wanted to care for the population because this strategy was artificial. It wasn't targeting the areas in which we wanted to serve the people. So, now we are struggling with the issue of how to take the whole concept of essential community providers and integrate them into a system in which they perhaps may be the best able to meet the needs, without creating a two-tiered system.

I think that is the challenge.

SNOW: In greater New York, Oxford has within its system some 11,000 physicians and over 100 hospitals. All of the hospitals and most of the specialists for our commercial members are also available to our government programs (Medicare and Medicaid). Right now, Oxford is licensed to serve Medicaid only in Brooklyn. Our primary care network in Brooklyn is very extensive; it has over 120 primary care physicians.

As Lois mentioned, our network is composed of additional providers beyond those who serve our commercial population. We also bring in other providers who only serve Medicaid and meet our credentialing criteria, such as community health centers and hospital-sponsored primary care centers. As to quality: we do not compromise our credentialing process to serve the Medicaid population. If physicians

don't meet our credentialing criteria, they don't come in. So, we have elevated the game when it comes to serving the Medicaid population. And we have expanded significantly the options for where Medicaid recipients can receive their care.

I would say generally that this situation holds true for most of the Medicaid managed care programs I am familiar with throughout the country. They have really expanded and elevated the game (the availability of care for Medicaid recipients).

QUESTION: Would you say the same thing for hospitals?

SNOW: Yes, I would. I would say that without question more hospitals are available because HMOs will make arrangements to transport Medicaid recipients for specialty services as needed to “centers of excellence. ” Recipients are not stuck in a community where the only option is the indigent care hospital. For example, Oxford in New York does not contract with the public city hospitals (Health and Hospitals Corporation or HHC). Members go to the private not-for-profit hospitals. The reason Oxford does not contract with HHC is that HHC has no ability to interface with managed care whatsoever. In addition, HHC in New York right now is fraught with tremendous problems of quality.

DELBANCO: To the degree there are data, most of the evidence points to the fact that poor people get less high-quality care than people who are not poor. We have been doing studies from the patient's perspective, asking patients about their experiences with care in this country and in other countries. We find that people who have fewer resources encounter more problems with care than those who have more resources.

WATTMAN: But if I could comment on that, I think the question is: Is that the medical system's failure or is it the supporting system's failure? I mean, if we look back at the medical assistance survey that Medica did, the barrier to access was not the delivery system itself, but rather the fact that people couldn't get to it, and if they got there, they couldn't understand the language or the providers couldn't articulate the language. So, there were social barriers as opposed to medical barriers.

KENNETH SHINE: A quick question for each person.

Mr. Snow, I don't understand how the Health Care Financing Administration can say it is more expensive to take care of Medicare

patients in an HMO than in a fee-for-service program and yet you are offering services for a high-risk population at 86 percent of the fee-for-service rate. Help me understand how that happens.

Ms. Wattman, I don't understand how you can take care of the kind of population for whom you need language translation services and the like in an IPA setting. And how do you know whether the individual provider in an IPA gives that 10 percent of patients the same kind of care that he or she gives the other 90 percent.

And Dr. Delbanco, what is wrong with expanding your market to Lexington, to the affluent suburbs? If it expands the base of individuals who are relatively low risk and increases the patient population that is cared for and doesn't cost so much, doesn't that provide an environment in which there is a higher probability, rather than a lower probability, that your hospital will be able to take care of poor people?

SNOW: In reference to the announcement that HCFA was not confident that managed care contained costs for Medicare, I do not believe that those comments accurately reflect either HCFA's opinion or the facts. I do know that when you move a population from one system to another, you are more likely, when you give people an option, to attract those people who are not currently ill because they are more willing to accept change. If I am currently ill and I am going to a certain doctor in a certain hospital, I am not going to go join somebody else and have my current care interrupted. So, it is true, in the early implementation of any program, you are likely to get a healthy population.

Does that mean those other alternatives are not working? The answer is no, because clearly you give that health plan some time, and the population they attracted who were healthy when they enrolled will ultimately start looking like the overall population. It is a timing issue. A snapshot in time taken early in the evolution of Medicare managed care might give a skewed view of managed care's effectiveness. The conclusion one draws from this immature data is not necessarily “let's stop enrolling people into managed care.” My answer—and, again, I am biased—is move everybody over. Then skimming can't happen and I guarantee we will save money. I guarantee we will have an efficient system.

WATTMAN: How can we deliver these services through an IPA model of close to 5,000 physicians? It is a challenge. We view our responsibility as a health plan as trying to remove the barriers so that

when the medical assistance patient presents at the physician's office or at the hospital, that patient presents as any other patient.

So, that means we have arranged the transportation with a multilingual staff. We have arranged for the interpretative services. We are working on how we arrange for daycare. We are going to be hiring social workers on our staff so that our physicians can, in fact, access those social workers to deal with the multiplicity of needs that are presented when that individual comes into the office. So, we try to replicate at the plan level the kinds of services that are necessary.

The question of how to guarantee that, in fact, all of our physicians are providing the kind of service or attention that is necessary to deal with those issues, I think, is at the heart of where we go with our network. We don't know what to do right now. We are seriously considering downsizing our network and working with those providers who want to serve the population. There is a real danger in doing that. When you start to lose the kind of access that has been part and parcel of our proposal, you start to develop the kind of two-tiered system that we are trying to move away from.

But if, in fact, someone presents themselves at a point of service and they are not welcome, that is not exactly what we want to be doing in health care reform. So, how do we balance the issue of access, ensuring that everyone has a societal responsibility to care for all populations, with making sure that when someone interacts with the system there is somebody who can meet their needs?

DELBANCO: I will tell you what is the problem with going to Lexington. I happen to live in Lexington, less than a mile away from our new facility. In fact, it is a sign of my basic masochistic tendencies that I don't practice there, because I drove into the hospital today in 6 degrees on the ice before I came down here. That was 17 miles, and I could have driven less than a mile.

Many of my neighbors are now going to our Lexington practice. They love it. For some, it means they get a third opinion, instead of a second opinion, on trivial ills. For many, it means that instead of driving half an hour to get to Beth Israel, they are going right next door. We spent $7 million on a new building in the center of Lexington. You know what $7 million for a new center in Roxbury would have meant to people who have no access to care now? A heck of a lot!

QUESTION: Oliver Fein from Columbia University in New York and a Robert Wood Johnson Health Policy Fellow this year here in Washington.

I was disturbed when David was talking. On the one hand, I saw myself as a young idealistic individual presenting a program and presenting it in its really pure, pristine form. I hope none of you here go away with the illusion that all managed care for Medicaid is, in fact, run the way David has described it.

I just talked to my wife, a pediatrician who works in New York City in a Health and Hospitals neighborhood family care center in Brooklyn. In the last week she had three patients who were enrolled almost without their knowledge in some managed care outfit in Brooklyn, thereby severing their relationship to her and at the same time being unable to get any form of service during this period of time. They had been brought into a program with absolutely no understanding of what they were getting into. So, the whole process of enrollment in HMOs is an enormously complex thing. And some say that, indeed, it is not the plan's problem to market, as Lois said, but rather is handled by the welfare authorities, which I am sure is what occurs in New York City. I am not saying this is a fault of your program, but one should recognize that that is a major problem.

John Eisenberg, now head of medicine at Georgetown University Medical School, used to always say to me that when he was in HealthPASS there were addicts whom he would see once a year, and it was delightful because he would get all the capitation payment for that patient and, yet the cost for that patient was extremely low. So, vulnerable populations have this paradox about them, that if one, in fact, delivers good service to them, they do cost more, but, indeed, frequently if you look at their use pattern, which sometimes is the best predictor actually of the cost of services from a risk assessment point of view, you will find that they underuse services and the result is that they are the low-cost group.

This becomes very interesting in terms of the paradoxes and the problems that arise. To make the comparison to fee-for-service, it seems to me, is also a major problem. Tom knows this. To some degree, those of us in a fee-for-service environment at the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center, I think, have in fact replicated and perhaps done just as well, if not better, than you have, David, in your managed care environment, in delivering services to a population, a vulnerable

population in Washington Heights, a group that is very sick that now does have 24-hour access to a physician. Our plan does provide continuity of care.

There is nothing intrinsic to the fee-for-service system that necessarily says that you can't do that. It is just that you are correct, if you are going to compare managed care to Medicaid mills, managed care, I hope, will do better, although I am not sure in every instance.

Finally, I would like to ask a few questions.

David, I was wondering: in your outcome studies, did you control in any way for severity of illness, to make the argument that managed care, in fact, does all of the things that you described, particularly influence mortality? Did you control for, in fact, whether those two groups were equally at risk in terms of their health status? I suspect you didn't.

Secondly, Lois, I was really interested in how we get managed care organizations to deal with the vulnerable populations if they are not paid more? You said that 10 percent of the population was enrolled in managed care, but they are 12 percent of your budget. So that already they are, indeed, costing more and I think there is a real dilemma if we go into health care reform and everything costs the same.

Finally, for Tom, is it possible that one could think of risk adjusting along a parameter called socioeconomic status? Not necessarily health status, which of course would give us a much finer predictor, but if we risk adjusted by socioeconomic status, could we, in fact, make your administrators a little bit more interested in serving that population?

SNOW: A couple of comments. I will answer your question, too, but one interesting point is that Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center in New York, as well as Columbia University, have enrolled all of their employees in Oxford. We have about 8,000 Columbia Presbyterian and University employees within our system. I think we have a very good relationship and we are currently in the process of discussing expansion into Harlem, working hand in hand with Columbia Presbyterian to do exactly the things we talked about.

I am familiar with the implementation problems that were referred to in Brooklyn. There is a specific HMO that had its hand slapped by the City of New York because they enrolled without fully educating members, which may be an argument for the government controlling the enrollment process to make sure people are adequately informed of their choices.

I will admit that in a voluntary enrollment situation, the incentives are a little bit dangerous. I prefer a mandatory situation. We make sure in our plan everyone is fully informed, but you cannot control that. Just as hospitals are different in how they handle opportunities to educate recipients, I think HMOs are different. You cannot lump them all in the same basket.

As it relates to the study in Philadelphia, I think I mentioned that an independent third party did the study. This third parry was hired by HCFA and the Department of Public Welfare for the State of Pennsylvania as part of the ongoing quality audit of the HealthPASS program.

The populations compared were identical. They lived in the three districts of Philadelphia not part of the mandatory demonstration program with environments identical to south and west Philadelphia. So, the acuity levels within those populations and the eligibility categories were compared apples to apples. And the results, although not scientific, can lead one to believe that over time, as people get used to a managed care system, they are better off.

I think more should be done to study better the outcomes from care delivered through managed care entities, especially to vulnerable populations. No truly scientific studies have been done up to this point in time. Some of what we talk about is from gut reaction and some is from superficial fact. However, the report that I talked about was a fairly extensive study and I would be happy to show that to you if you would like.

WATTMAN: I would just echo the comments on the marketing issue in the mandatory versus voluntary system. When the demonstration project was created in Minnesota in the mid-eighties, it was a voluntary program with a third of the population and we had a nightmare in terms of enrollment and selection issues. People were assigned to plans and did not know to which plan they had been assigned.

Now, a mandatory situation controlled by the county is a much more reasonable approach. Everyone is much better informed. I have to say, though, that, back to the study, remember, about the refrigerator, this is how naive we were as a health plan. We were sending out all of our packets of materials. How many people here read their health care contracts?

I am a lawyer. I write the health care contracts. And I don't read the health care contracts. If you get a contract an inch thick from your

health plan and you don't speak English, what do you do with it? You throw it out. So, at least we have progressed to the point where we have multiple languages on the envelope that says here is how you call for an interpreter. Let us know.

But, to answer the second comment and then response to your question on plan participation. There is no accountability in a fee-for-service system because a fee-for-service system is not a system of care delivery. That is the fundamental difference between a managed care option and fee for service.

Who is accountable in a fee-for-service system when the immunization rate is not achieved? The public? The public health infrastructure? Society? I know who is accountable in my plan. Our plan is held accountable when our immunization rates for the medical assistance population are not what they are supposed to be.

The key difference between what we have today and a reformed system is that we are talking about systematized delivery of care, where there is accountability not only for costs, but for outcomes associated with delivering that care.

In response to the question on how do we get other plans to all take their fair share: We have a statutory requirement in Minnesota that says all plans that take care of state employees, that participate in worker's compensation, that deal with the risk pool for the uninsurable—you name it—all plans that are hooked into the state have to provide health care coverage under the medical assistance program. We have not implemented it yet. So, our largest carrier in Minnesota—Blue Cross and Blue Shield—does not participate in medical assistance. Our staff model health plan—Group Health—which has about 580,000 enrollees, has 2,000 medical assistance enrollees.

We are challenging our sister plans to say come on in. It is an interesting experience. We are saying there is a societal responsibility that we have as managed care organizations to care for this population, and if we believe in managed care, then managed care doesn't just work for the self-insured companies and the healthy populations. The tools of managed care can be used effectively to meet the needs of the vulnerable population.

DELBANCO: I have to say, Lois, that, while I have written lots about the problems of fee-for-service populations and practices, in my practice, which is fee for service, we have high immunization rates and we clobber each other with regularity when we are not giving high

quality of care. So, I think there can be accountability in a fee-for-service system.

A quick response to Dr. Fein about adjusting for socioeconomic mix: Yes, that is a possibility. In England, Brian Jarman, who was the first professor of primary care there, developed the “Jarman Index. ” He counted how many people live in an apartment, for example, as one measure of socioeconomic mix. Some of the capitation in England is based on that. There are many ways of doing it. We just have to get better at it, and we are still in the early stages.

COMMENT: I am Joel Alpert, pediatrician, and I have spent most of my career in the inner city, the last 21 years at Boston City Hospital.

What I am taking away from the passion of this evening, and I am going to put myself under that umbrella—it is a passionate debate—is that I wish we had more data to support some of the things that we are saying. I am impressed, for example, that you have recognized and found in your programs the special, enriched efforts that it takes to care for at-risk populations.

We have no magic bullet for violence and teenage pregnancy and drugs and the other issues we are struggling with, and so long as we have families who have to choose between heat and eat, none of us are going to succeed. I do not take from this discussion that managed care is the answer, but rather the recognition of the special needs of the populations that we are caring for. They might be disabled. They might be ventilator-dependent children. And they are going to take extraordinary efforts on all of our parts.

This leads me to the one major point I want to make, which is a plea for us not to loose sight in Washington, D.C., of the single-payer option, which, after all, will render the financing side of this more or less moot, as far as I am concerned, and will let us all then conduct our various demonstrations.

Another comment about the managed care option and at-risk populations: based on my considerable experience, I don't know whether the number is 75 percent, 80 percent, or 85 percent of families in the inner city are every bit as middle class, and have the same aspirations, as every one of us sitting in this room, and we must not lose sight of that as we talk about the at-risk nature and the special populations that we are talking about.

One last comment. I promised my mother something today because she said to me that she didn't want me to make this trip because she is 92 and critically ill. I have learned that the way to make a point in Washington these days is to tell an anecdote. My mother has a malignancy and the malignancy has spread widely. And because she has a malignancy, she has gone into hospice, and because she has gone into hospice, her care is paid for under Medicare.

And she looks at the wonderful Connecticut hospice and she asks, “Who is paying for this?” And I am able to say to her, “You are. Because my dad worked his whole life, because of Social Security, because you are entitled to it.” But if she didn't have cancer and she were 92 years of age and she had to go into a nursing home because she could no longer live independently she would probably have to use all her life savings and end up impoverished and on Medicaid.

That is a choice that no one in this country should have to make, forced into poverty by the nature of their illness. Here I am straying into a geriatric problem as a pediatrician, but after all, it is my mother and I am entitled to do that. And besides I told her that I would tell everyone here tonight that she was a great lady and she would feel good about the fact that I came down.

But just think about that. The fact that she has a malignancy means that her dignity is preserved and she can be covered under Medicare, which comes closer to a single-payer system than anything else that we have in this country, only in this case only for those over 65. And I think we should keep that in consideration as we try and figure out in this country how we are to remove as many of the barriers to access as people need removed.

QUESTION: My name is Janet O'Keefe. I am with the American Psychological Association.

Most of what we have talked about tonight in terms of vulnerable populations has focused on the poor. There is another concern about managed care, a major concern for another type of vulnerable population. The previous speaker just alluded to them—they are people with disabilities. I am speaking not only of those people with mobility impairments, but also persons with low prevalence diseases about which general practitioners may not be as knowledgeable as specialists.

There is a lot of concern among the disabled community about lack of access to specialists, lack of access to specialized services, very

low benefits for things like rehabilitation, durable medical equipment, and the long-term services that these people need. They feel that managed care, by definition, will not meet those needs because of a lot of problems. One is just the low level of basic benefits for these services, as well as the incentives within the capitation model not to refer to specialists.

I would like it if you would address those concerns.

SNOW: I can speak from both my Philadelphia and New York experiences. The benefits offered in both cases were far more than the fee-for-service Medicaid systems that the enrollees originally were in. For example, in New York they have what they call utilization thresholds, which cap the number of encounters you may have with a provider each year. You are allowed 12 office visits per year. If you are a home-relief recipient, you cannot get any more care after that. They have these artificial thresholds for accessing the system.

When you join the managed care program, you have unlimited access to care. At Oxford, when a person is diagnosed with a catastrophic or chronic illness that clearly requires specialist care, we do not make our member go to a primary care doctor every single time they need to access that specialist. We link that member to a specialist and that specialist keeps the primary physician informed because, should that member develop an unrelated illness, you want the primary physician in the loop. We recognize that a “gatekeeper” under certain circumstances can be a barrier to care, especially for those who have difficulty with transportation.

As far as mental health and disabilities are concerned, I know that, especially in the mental health and substance abuse community, there is tremendous fear of managed care. Mental health and substance abuse providers are advocating a carve out for their specific diagnoses, so that if you have a mental illness or a substance abuse problem, you no longer are in the managed care plan. You come back out and you go back to the old fee-for-service system.

I am very much against that because that encourages lack of continuity. That flies in the face of what we are trying to accomplish. I think what needs to happen and what we are trying to do is that we work with those specialty groups that have unique capabilities so that we can, in fact, develop systems that augment people's access when they need it. That, really, when you look at Medicaid, is the name of the game: making sure you have access early, at the onset, because the real

value in the system is when you can avoid the unnecessary use of the most expensive settings within our health care system.

I think that the groups you have talked about have been so concerned about managed care that they haven't sat down and tried very hard to work with the managed care providers. It is starting to change now because they see reform and realize it is time to change.

QUESTION: I am going to piggyback on the same issue. I am Alan Bergman with the United Cerebral Palsy Association.

As we have looked at the research and the data—and perhaps we didn't have yours—most of the managed care programs in this country that have operated under Medicaid specifically have excluded SSI recipients because the managed care system didn't have the research base, didn't have the data, didn't want to get into the risk business to see how much more on the average these folks were going to cost.

So, I think we have great trepidation about saying that in one wholesale sweep on January 1, 1996, the typical person with chronic conditions or severe disabilities is going to get thrown into a system that has historically rejected it for a variety of reasons. And, also, that system has no database (and we are hearing that confirmed here) to say whether it is a capitated rate or a capitation with an extension beyond it for chronic conditions.

Again, I don't know Oxford, but I know in a lot of the places that we have contacted, if we do not have a pediatric cardiologist available, if we do not have an orthopedist who specializes in pediatric orthopedics, if we do not have the allied health professions, the occupational therapists, the physical therapists, the speech language folks available, then we are going to potentially expose our constituency to some real disasters.

WATTMAN: One quick comment with respect to that: I think the reason that we don't have some of the populations covered by managed care is not because of the managed care plans' unwillingness to do so, but because of the political tough fight that we have just heard talked about in the last couple minutes with respect to populations who do not want to be included in managed care organizations because of the concerns that have been articulated.

From the standpoint of a managed care organization, we believe that we have some unique resources that can be brought to the table. I do agree with you however, that a learning and adjustment time is needed

for managed care organizations to respond in the most effective, high-quality way to the needs of the populations we have just been talking about.

You heard me describe the evolutionary process that we went through with some of the special needs populations that we serve. That is a sound way to proceed.

GROSSMAN: Thank you all for a very informative discussion period.