Part 3

The New Definition and an Explanation of Terms

The provisional definition of primary care adopted by the IOM Committee on the Future of Primary Care follows:

Primary care is the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community.

Each term in the definition is summarized in the box below and is explained in the text following the box.

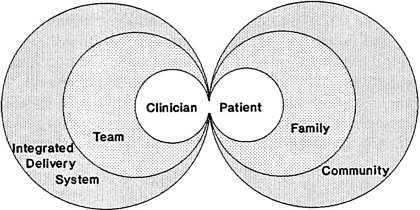

Although the new definition is based on the 1978 IOM definition, it recognizes three additional important perspectives for primary care: (1) the patient and family, (2) the community, and (3) the integrated delivery system. The 1978 IOM report addressed the first perspective, and the 1984 COPC report addressed the second. In recognizing the increasing importance to primary care of the integrated delivery system, this report addresses all three. The new definition thus stresses the importance of the patient-clinician relationship (a) as understood in the context of the patient's family and community, and (b) as facilitated and augmented by teams and integrated delivery systems.

The figure illustrates this committee's view that the patient-clinician relationship is central to primary care. The patient and primary care clinician interact with one another as appropriate and also with others in the community and the health care delivery system. The shaded areas in the figure are fields

|

DEFINITION OF PRIMARY CARE Primary care is the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community. An explanation of each term or phrase in italics follows. Page numbers indicate the beginning of the text discussion. Integrated is intended in this report to encompass the provision of comprehensive, coordinated, and continuous services that provide a seamless process of care. Integration combines events and information about events occurring in disparate settings and levels of care and over time, preferably throughout the life span (see p. 22). Comprehensive. Comprehensive care addresses any health problem at any given stage of a patient's life cycle (see p. 22). Coordinated. Coordination ensures the provision of a combination of health services and information that meets a patient's needs. It also refers to the connection between, or the rational ordering of, those services, including the resources of the community (see p. 25). Continuous. Continuity is a characteristic that refers to care over time by a single individual or team of health care professionals (“clinician continuity”) and to effective and timely communication of health information (events, risks, advice, and patient preferences) (“record continuity”) (see p. 27). Accessible refers to the ease with which a patient can initiate an interaction for any health problem with a clinician (e.g., by phone or at a treatment location) and includes efforts to eliminate barriers such as those posed by geography, administrative hurdles, financing, culture, and language (see p. 28). Health care services refers to an array of services that are performed by health care professionals or under their direction, for the purpose of promoting, maintaining, or restoring health (Last, 1988). The term refers to all settings of care (such as hospitals, nursing homes, physicians ' offices, intermediate care facilities, schools, and homes) (see p. 21). Clinician means an individual who uses a recognized scientific knowledge base and has the authority to direct the delivery of personal health services to patients (see p. 20). |

|

Accountable applies to primary care clinicians and the systems in which they operate. These clinicians and systems are responsible to their patients and communities for addressing a large majority of personal health needs through a sustained partnership with a patient in the context of a family and community and for (1) quality of care, (2) patient satisfaction, (3) efficient use of resources, and (4) ethical behavior (see p. 30). Majority of personal health care needs refers to the essential characteristic of primary care clinicians: that they receive all problems that patients bring—unrestricted by problem or organ system—and have the appropriate training to manage a large majority of those problems, involving other practitioners for further evaluation or treatment when appropriate (see p. 21). Personal health care needs include physical, mental, emotional, and social concerns that involve the functioning of an individual (see p. 21). Sustained partnership refers to the relationship established between the patient and clinician with the mutual expectation of continuation over time. It is predicated on the development of mutual trust, respect, and responsibility (see p. 20). Patient means an individual who interacts with a clinician either because of real or perceived illness or for health promotion and disease prevention (see p. 18). Context of family and community refers to an understanding of the patient's living conditions, family dynamics, and cultural background. Community refers to the population served, whether they are patients or not. It can refer to a geopolitical boundary (a city, county, or state), to members of a health plan, or to neighbors who share values, experiences, language, religion, culture, or ethnic heritage (see p. 18). |

Figure: The interdependence of primary care. The centrality of the patient-clinician relationship in the context of family and community and as furthered by teams and integrated delivery systems.

this committee newly emphasizes in this report. On the patient side, the family and community provide the context in which to understand and assist the patient. On the health care delivery side, the team and integrated delivery system provide the means for extending and improving the provision of primary care. One challenge that faces health care practitioners, policymakers, and administrators is how to foster and maintain such patient-clinician relationships in a complex, integrated delivery system. A correlative challenge is how to realize the potential benefits of these organizations and the interdependent work of health professionals in improving patients' health. The committee will address these issues in its full report.

Patient

By the term patient, this committee means an individual who interacts with a clinician either because of real or perceived illness or for health promotion and disease prevention. In primary care systems not all people are patients. People are usually patients at one time or another, but most of the time they are simply individuals going about their lives. They may need advice, information, or periodic physical examinations for preventive care. Wherever the term patient is used in this report, it is intended to mean individuals who seek care, whether or not they are ill at a given time.

Family

Some primary care systems may be organized to care for entire families over the span of life—infancy, childhood, adolescence, child-bearing years, maturity, and advanced ages. Other primary care clinicians, for example, pediatric nurse practitioners, care for patients of a particular age. Use of the term families in this report also acknowledges their caregiving roles, the concerns of family members, and the impact of family dynamics on health and illness. The phrase context of family and community in the definition refers to an understanding of the circumstances and facts that surround a patient, such as the patient's living conditions, family dynamics, work situation, and cultural background.

Community

The community refers to the population potentially served, whether its members are patients or not. Community can refer to a social group residing in a defined geopolitical boundary (a city, county, or state), to enrollees in a health

plan, or to neighbors who share values, religion, experiences, language, culture, or ethnic heritage. The use of the term community draws attention to the different perspectives that need to be addressed. On the one hand, primary care needs to be concerned with the care that primary care clinicians deliver to individuals. This more traditional and familiar area of primary care addresses the care and outcomes of individual patients. In its broadest sense, primary care must also be linked to the larger community and environment in which people work and live. This requires that primary care clinicians be aware of what may be happening in the community—such as occupational dangers, patterns of childhood injuries, patterns of lead poisoning or other environmental hazards, homicides, issues of domestic violence, and epidemics. This also requires that primary care clinicians know the major causes of mortality and morbidity for the community served.

Health care needs and objectives may not be the same for individuals and communities or for different individuals or different communities. Individuals have particular health care needs; the community has a broader perspective that emphasizes improving health status2 and reforming the way care is delivered. An integrated delivery system has the potential for melding both perspectives.

Prevention of illness and promotion of healthful lifestyles are critical components of good health. The benefit gained from these elements and from broader public health activities as compared to medical care can vary. For example, 10- to 24-year-olds are likely to gain much more in improved health and rates of survival by preventing injuries and damage due to violence, motor vehicle accidents, or substance abuse than they are from direct, episodic, medical care (IOM, 1994a).

Many barriers to better health are related to socioeconomic status, education, and cultural and behavioral components. At times these factors extend far beyond health care or health promotion and disease prevention in their usual sense. Primary care clinicians are not “responsible” for the environment, jobs, housing, or violence. Primary care clinicians do, however, need to know about the context of their patients' problems. Health promotion activities within the primary care setting should (a) incorporate information about the needs of the community and its health problems, and (b) provide information to the community and those involved in its public health efforts.

|

2 |

Health status refers broadly to physical, mental, and social function. Although health status is largely determined by environmental and personal variables, health services should, to the extent possible, contribute to improved health status. |

Clinician

The term clinician refers to an individual who uses a recognized scientific knowledge base and has the authority to direct the delivery of personal health services to patients. A clinician has direct contact with patients and might or might not be a physician. The committee's recommendations about who should provide primary care will be addressed in the full IOM report. Additionally, primary care clinicians might turn to other individuals both with and without health care training for their assistance and skill in particular areas. Examples of individuals other than primary care clinicians who can contribute to primary care might be physical therapists, nutritionists, and social workers. In Hispanic communities, primary care clinicians might turn to layworkers known as a promotoras for outreach and community education.

This committee has chosen to use the term clinician in contrast to other familiar terms such as provider. Provider is commonly used not only to refer to individuals who deliver care but also to denote facilities or organizations that provide health care, such as hospitals or health plans. In medical centers, a clinician refers to someone with direct patient care responsibilities; in using the term clinician, then, this report underscores the importance of a relationship between a patient and an individual who uses judgment, science, and legal authority to evaluate and diagnose patient problems and to manage them.

Partnership

The term sustained partnership refers to the relationship established between the patient and clinician with the mutual expectation of continuation over time. It is predicated on the development of mutual trust, respect, and responsibility. As an ideal, primary care occurs within the context of a personal relationship between a patient and clinician that extends beyond an episode of illness. Such a relationship, developed over time, fosters a sense of trust and confidence. The partnership relation facilitates tailoring a specific intervention or specific advice to the needs and the circumstances of a particular person. A bond to someone you trust may be healing in and of itself. This relationship is essential when guiding patients through the health system.

Although it denotes participation by both clinician and patient, the term partnership does not necessarily imply equal roles for clinicians and patients. In some cases patients desire and should have a large role in identifying health problems to be addressed or deciding how they should be addressed. In other cases a patient may prefer a relatively small role and delegates most decisionmaking to a clinician. A dependent relationship may be reassuring and even healing in some circumstances. The term partnership means that the patient

and clinician together agree on goals and the ways to reach them. It also implies that ideally the patient is treated as a whole person whose values and preferences are taken into account.

The committee that developed the 1978 IOM definition viewed the primary care clinician as a manager for a specific episode of care. The current IOM committee broadens that view considerably. It emphasizes the need for the primary care clinician not only to manage a given health concern and address issues of preventive health care, but also to act as an agent for the patient in a larger health system so that the patient knows who is making decisions and coordinating his or her care.

This personal relationship is more important to some people in some circumstances than it is to others. Although in many circumstances patients may feel quite comfortable knowing that information is in their medical record where all those involved in their care can find it, patients often prefer (when they can) to see a particular clinician. Challenges remain about how to structure a team so that personal relationships are supported, and the full IOM report will address these issues.

Use of the term partnership is also intended to convey the idea that both clinicians and patients have responsibilities. Clinicians are accountable as described below; patients are responsible for helping to sustain the relationship, for conveying complete and timely information to the primary care clinician, for aspects of their health that are affected by obtaining preventive care, for lifestyle choices, and for seeking care as appropriate, for following instructions, and observing treatment effects and side effects.

Health Care Needs and Health Care Services

The term personal health care needs includes reference to physical, mental, emotional, and social concerns that involve the functioning of an individual. The term health care services refers to an array of services that are performed by health care professionals or under their direction, for the purpose of promoting, maintaining, or restoring health (Last, 1988). The term refers to all settings of care (e.g., hospitals, nursing homes, clinicians ' offices, community sites, schools, and homes). Health care services address physical, mental and emotional, and social functioning. The last concept pertains to any health conditions that impede an individual 's ability to fulfill his or her social roles, such as ability to attend school, work at gainful employment, or perform as a parent.

Integrated

A key term used in this definition is integrated. It can be defined as “combining separate and diverse elements or units so as to provide a harmonious, interrelated whole” (see Webster, 1981; Random House, 1983). Integrated as used in this report is intended to connote multiple important concepts: the provision of comprehensive, coordinated, and continuous services that represent a “seamless” process of care. Those three terms from the 1978 IOM definition—comprehensive, coordinated, and continuous—are described below. The committee's use of the term integrated when describing personal health care services should not be confused with the widely used term as applied to horizontal and vertical integration in integrated delivery systems. To integrate primary care fully, however, primary care clinicians are likely to practice in teams and in such integrated delivery systems.

Some care settings are very small systems, for example, a solo clinician, nurse, one administrative person, and referrals as needed for specialty care. One can envision, however, the development of primary care networks using computers to link smaller systems of care into broader ones that are facilitated by information networks (IOM, 1991). Although such primary care networks might not include a full range of services, such developments would move small systems toward the sort of integration envisioned by the committee.

Integration might be fostered in other ways. An example would be linking specialist (e.g., dermatology, psychiatry) or subspecialist (e.g., gastroenterology, pulmonology, cardiology) services for a patient with a chronic illness with a primary care clinician (either within the subspecialty practice or elsewhere) who can continue to give primary care.

Comprehensive

First Contact. One element of comprehensiveness is sometimes referred to as first contact. In a well-developed and functioning system, primary care is the usual and preferred route for entry into the health care system (although not necessarily in all circumstances). In the simplest model, the primary care clinician receives patients regardless of the disease or organ system involved and addresses a given patient's problem. This function may require sorting out a mixture of ill-defined symptoms, or it may call for fairly straightforward treatment. This simplest of models, however, should be flexible enough to allow patients to enter at various points or to skip given steps (e.g., authorizations) based on their needs and safety as well as on efficiency considerations. The model is not intended to describe a regimented or restrictive processing system,

and indeed such a system would be antithetical to the committee's future vision of primary care.

First contact with a primary care clinician may lead to referrals to other resources—for example, to a nurse practitioner for diabetic counseling or to a cardiologist for subspecialty care. In some cases, self-referral by a patient may be appropriate—for example, for recurrent problems previously treated by another specialist or subspecialist or refractions for eyeglass prescriptions. Information about these encounters should be provided to the primary care clinician.

The descriptor first contact is not, however, a sufficient or unique attribute for defining primary care. It is not unique because some first contact events do not represent primary care—for example, those that occur through an occupational health service, an emergency room, or at a health fair booth for cholesterol screening. Such encounters can be integral to the patient 's health care, and information gathered should be communicated to the primary care practice.

Furthermore, first contact is not sufficient to define primary care. Insofar as it has come to imply the restriction of primary care to a triage function, it neglects the other characteristics of primary care included in this report, specifically, comprehensiveness.

A derivative term is gatekeeper. In many circles, the term gatekeeper has been used to describe the function of using the experience and judgment of the primary care clinician to determine whether diagnostic tests are necessary, whether a patient's problem can be handled by the primary care practice, or whether a person needs to be evaluated or treated by another specialist or subspecialist. Patients view gatekeeping with suspicion because they fear that efforts to control use of services and to manage costs may ultimately work to the detriment of their health. By contrast, many managers, benefits officers, and policymakers view gatekeeping with enthusiasm because they see it as a way of rationalizing, if not restricting, the use of health care resources. The term gatekeeper, therefore, has come to have a pejorative connotation when primary care is reduced to the function of managing costs and especially when it implies that the gate is kept closed most of the time. This committee categorically rejects the view that the primary care clinician acts mainly or exclusively as a gatekeeper.

The Scope of Primary Care. Comprehensive care is intended to mean care of any health problem at a given stage of a person's life. It includes ongoing care of patients in various care settings (e.g., hospitals, nursing homes, clinicians' offices, community sites, schools, and homes). Ideally, the primary care clinician listens to the patient, evaluates, makes diagnoses, manages, and screens for other health care problems. He or she educates and communicates with the patient and others who may be involved. He or she involves other specialists when

appropriate and assumes ongoing responsibility for maintaining contact with and care of the patient and assuring that the care provided is suitable. The IOM definition refers to a large majority of personal health care needs. That phrase refers to the essential characteristic of primary care clinicians: that they receive all problems that people bring—unrestricted by problem or organ system—and have the appropriate training to manage a large majority of those problems, involving other health professionals for further evaluation or treatment when appropriate, and continuing to act as advocates for their patients.

Primary care addresses a mixture of health problems along the spectrum of disease as they occur singly or in combination within a single individual. Ideally, primary care clinicians elicit the full range of patient concerns, whether physical or psychosocial, and are sensitive to the concerns and circumstances that accompany a patient's symptoms.

Not all patient problems represent deviations from normal health that require medical action. Thus, primary care clinicians have a special responsibility to be sensitive to those concerns that are appropriately labeled health problems and those that are not or that could be made worse by medical intervention.

Some portion of patient problems—based on a particular individual's needs, on safety, or on efficiency considerations—may not be manageable by the primary care clinician. Some portion may require the expertise of other health professionals, other specialists, or subspecialists. The distribution of problems that would be expected to be seen in a primary care practice will be studied by the committee and discussed in the full IOM report. The following categories of service are within the scope of primary care as defined by the committee:

-

Acute care.3 (a) Evaluate patients with a symptom or symptoms sufficient to prompt them to seek medical attention. Health concerns may range from an acute, relatively minor, self-limited illness to a complex set of symptoms that could be life threatening, to a mental problem. Arrange for further evaluation by specialists or subspecialists when appropriate. (b) Manage acute problems or, when beyond the scope of the particular clinician, arrange for others to manage the problem.

-

Chronic care. (a) Serve as the principal provider of ongoing care for some patients who have one or more chronic diseases, including mental disorders, with appropriate consultations. (b) Collaborate in the care of other patients whose chronic illnesses are of such a nature that the principal provider of care is another specialist or subspecialist. The primary care clinician manages intercurrent illnesses, provides preventive care (e.g., screening tests,

|

3 |

The usual distinction between acute and chronic is not always exact. Duodenal ulcers and depressive disorder are examples of conditions that may be neither clearly acute nor clearly chronic. |

-

immunization, counselling about life style), and incorporates knowledge of the family and the patient's community. An example would be managing the dermatitis, hypertension, or upper respiratory infection of a patient who is under the care of a rheumatologist for rheumatoid arthritis.

-

Prevention. Provide periodic health assessments for all patients, including screening, counseling, risk assessment, and patient education. Periodic health assessments are a natural part of primary care. Many major diseases have a typical course over time. Primary care must reflect an understanding of risk factors associated with these illnesses, including genetic risks, and of the early stages of disease that may be difficult to detect at their outset.

-

Coordination of referrals. Coordinate referrals to and from other clinicians and provide advice and education to patients who are referred for further evaluation or treatment.

Coordinated

Coordination ensures the provision of a combination of health services and information that meets a patient's needs and specifically means the connection within and across those services and settings—putting them in the right order and appropriately using resources of the community. The goal is to focus on interactions with patient and family and their health concerns, clarify clinical care decisions, advise hospitalized patients and their families, and help patients and their families cope with the social and emotional implications of disease or illness.

The primary care clinician will often be the principal clinician of inpatient care for certain conditions that require hospitalization (e.g., pneumonia) but not the services of other specialists or subspecialists. He or she follows hospitalized patients, even those whose principal clinician may be a another specialist or a subspecialist. The primary care clinician brings knowledge of a patient and family history and social perspectives to bear on that episode of care. He or she may also manage other aspects of the patient's care during hospitalization, for example, by continuing to manage the diabetes of a patient who is hospitalized for a hip fracture. The primary care clinician also coordinates a patient's transition between health care settings—for example, hospital and home, home and nursing home, or between clinicians' offices.

Teams. An individual may need the benefits of a set of activities that entail an array of services. The sorts of tasks required are varied and require efficient management of both care and available resources. The emphasis in this report on primary care teams acknowledges that we need not depend on a single person to organize and provide all expertise and care. Much primary care is rendered

by single clinicians, but increasingly teams are being required to manage the health problems presented to primary care practices.

A team is a group of people organized for a particular purpose. It may be organized to subdivide tasks, increase accessibility, extend the expertise of a health professional by drawing on several disciplines, or delegate tasks that do not require a clinician's level of training. The organization of health services for a defined population can be greatly facilitated by using teams with a mix of practitioners who together are best suited to meet the range of needs of a given patient or of a population. A pediatric practice may for instance have a group of pediatricians, a pediatric nurse practitioner, and a receptionist who work together giving general pediatric care. Other multidisciplinary groups might be organized for the care of those with particular problems, for instance, children who have been abused. Yet another case in point is a geriatric practice team that includes a social worker, dietitian, physical therapist, geriatric nurse practitioner, and geriatrician.

Team composition may vary by specialty, subspecialty, clinician interest, expertise, and resource availability. The population served by a team may vary by gender, age, health concerns, and social problems. The composition of primary care teams depends on the needs of the patients and the population served: The team involved in providing primary care services to a relatively healthy, employed group of people would be different from that needed to manage a group of elderly retired persons or patients with chronic illnesses. Both of those teams would be quite different from ones that are organized to care for patients with complex social and environmental problems such as domestic violence.

As indicated in the Figure, the committee views the team as an extension of the patient-clinician relationship, not as an alternative to it. Although primary care can be delivered by teams, exemplary primary care requires that one or more members of that team develop a close one-on-one relationship with the patient.

Interaction with Communities. The effective coordination of health care services requires an intimate knowledge of the communities in which those services are delivered. Such coordination requires:

-

knowledge of other health care agencies, resources, and institutions within the community (e.g., the availability of classes teaching cardiopulmonary resuscitation or of smoking cessation support groups);

-

an understanding of the financial concerns of patients and communities;

-

an understanding of the cultural, nutritional, and belief systems of patients and communities that may assist or hinder effective health care delivery;

-

an understanding of day-to-day life-style patterns of patients and in communities that may enhance or diminish coordination efforts (i.e., work, transportation, school, child care); and

-

a functional information system.

Continuous

The term continuous means “uninterrupted in time, without cessation; being in immediate connection or spatial relationship” (Random House, 1983). In this report, continuity is a characteristic that refers to care over time by a single individual or team of health professionals (“clinician continuity”) and to effective and timely communication of health information (about events, risks, advice, and patient preferences)( “record continuity”). It applies to both space and time. It combines events and information about events occurring in disparate settings, at different levels of care, and over time, preferably throughout a person's life span. Continuity encompasses patient and clinician knowledge of one another, and the effective and timely communication of health information that should occur among patients, their families, other specialists, and primary care clinicians. Some means of ensuring continuity are found in integrated delivery systems.

Clinician continuity, when achieved, is an effective way to provide continuity in primary care. The patient record is essential, but it does not substitute for clinician continuity because, for example, information such as family, sexual, or emotional problems is often intentionally excluded from the record because of concern that the information might not be kept confidential. Knowledge of a patient 's usual ways of dealing with symptoms such as pain is another example of how care can be dramatically altered by sustained personal relationships between clinicians and patients. A patient's story is dynamic, not static, and a primary care clinician who knows a patient understands when it is appropriate to use or disregard medical information from the patient's record because it is outdated, irrelevant, or wrong.

Given our propensity in the United States for moving and for changing employers, insurance plans, and household composition, however, such a goal of clinician continuity is not likely to be perfectly realized. At an earlier time in our nation's history, a general practitioner might care for a couple, deliver their babies, and see those children grow, marry, and have children of their own. The physician carried information about those individuals and families in his or her head. Now the amount and complexity of information that must be recorded about patients is steadily increasing. If continuity is to be an element of primary care, it will likely be achieved by ensuring that relevant, accurate information is available to all clinicians, even when the relevance of data is not immediately apparent, and this reflects the goal of record continuity.

Increasingly sophisticated clinical (as opposed to financial) information systems are being developed rapidly, and the progress of computer technology has led to efforts to aggregate health data from many sources such as hospitals, offices, pharmacies, and laboratories. Such data aggregation has tremendous potential for ensuring the continuity of medical information. Two IOM reports, The Computer-Based Patient Record: An Essential Technology for Health Care (1991) and Health Data in the Information Age: Use, Disclosure, and Privacy (1994b), have explored the benefits and risks of computer-based patient records and community-level information databases. Meeting the need for continuity of care is a significant element of computer-based patient records.

Continuity can apply to an integrated delivery system, a primary care practice or team, and a single primary care clinician. Although the ideal may be an individual seeing the same clinician at each visit, there may be trade-offs between continuity and access. Continuity of clinician may be more important for some people and in some circumstances than others. For example, for a patient with hypertension who makes appointments at regular intervals, it is particularly helpful to both the clinician and the patient to ensure continuity over a succession of visits so that progress and the need to adjust medications can be assessed. Continuity can also be a major source of satisfaction both to patients and clinicians as it fosters the long-term relationships that represent, for many clinicians, a significant reward of medical practice.

Sometimes, however, patients have an acute illness or injury and would prefer quick access to a clinician who might be known to them as a member of a team or practice or might even be a complete stranger at an urgent care center or emergency room. Balancing the competing values of continuity and access represents one of primary care's important challenges and one for which integrated delivery systems may offer some solution.

Accessible

The term accessible means “easy to approach, reach, enter, speak with or use” (Random House, 1983). It refers to the ease with which a patient can initiate an interaction for any problem with a clinician (e.g., by phone or at a treatment location). It includes efforts to eliminate barriers such as those posed by geography, administrative hurdles, financing, culture, and language.

Accessibility is also used to refer to the ability of a population to obtain care. For example, having public insurance coverage does not guarantee access to care if no local clinicians are willing to see individuals with that form of insurance. Accessibility is also a characteristic of an evolved system of which primary care is a basic unit. Potential enrollees of a health plan want to know whether they have “access” to other specialists or subspecialists, how to obtain that access, and

where they would need to go to be seen on a weekend or holiday, for example. Determining the level of accessibility that has been achieved is a judgment that is based on a community's needs and expectations as defined by members of the community and based on their experiences in obtaining the care they desire.

Clearly, no clinician can be accessible at all times to all patients. Integrated delivery systems seek ways to ensure timely care, to meet patient expectations, and to use resources efficiently. For example, integrated delivery systems may establish policies regarding maximum waiting times for an urgent appointment, periodic health examinations, coverage when a clinician is out of the office, and getting patients into substance abuse treatment programs on a weekend.

Primary care is a key to accessibility because it can provide an entry point to appropriate care. It is the place to which all health problems can be taken to be addressed. People do not have to know what organ systems are affected, what disease they have, or what kind of skills are needed for their care.

Accessibility also involves “user friendliness.” It also refers to the information people have about a health system that will allow them to navigate the system appropriately. It means directions for health plan members about where to call for certain information or how to get help in an emergency; the ability to get health information and information about self-care or community resources; use of computer technologies to obtain information; and obtaining one's own medical record. Access to guidance and data enhances patients ' ability to care for themselves and act responsibly in relation to their health care system.

Administrative barriers to accessing health services deserve special attention. Even when individuals have a benefit package that provides coverage for a given service, administrative hurdles may sometimes be so burdensome, whether by intention or not, that the service is effectively denied. For example, the approval process for obtaining mental health care is, in some organizations, so intimidating or personally intrusive that individuals may be unable to get timely assistance or even any adequate care at all.

Accessibility can also be increased by the use of telecommunication and information management technologies. For example, clinicians in rural practices can use telecommunication to obtain subspecialist consultations in the reading of diagnostic tests for heart function and for reading slides of pathology specimens.

Accountable

The term accountability in a general sense means the quality or state of being responsible or answerable. It also means “subject to the obligation to report, explain, or justify” (Random House, 1983). Like all clinicians, primary care clinicians are responsible for the care they provide, both legally and ethically.

Primary care clinicians and the systems in which they operate are, in particular, answerable to their patients and communities, to legal authorities, and to their professional peers and colleagues. They can be held legally and morally responsible for meeting patients ' needs in terms of the components of value—quality of care, patient satisfaction, efficient use of resources —and for ethical behavior.

Quality of Care

Primary care practices are accountable for the quality of care they provide. A 1990 IOM report, Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance, defined quality of care in the following way:

Quality of care is the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge [IOM, 1990, p. 21].

Focusing on outcomes requires clinicians to take their patients' preferences and values into account as together they make health care decisions. The phrase current professional knowledge in the above definition underscores the need for health professionals to stay abreast of the biomedical knowledge within their professions within their professions and to take responsibility for explaining to their patients the processes and expected outcomes of care. It includes the need to maintain high standards for licensure, certification, and recertification for all individuals and institutions that provide health care. In accordance with this definition, primary care practices must be able to address three fundamental quality-of-care issues in their assessments of quality and in the steps they take to improve it (IOM, 1990):

-

Use of unnecessary or inappropriate care. This makes patients vulnerable to harmful side effects. It also wastes money and resources that could be put to more productive use.

-

Underuse of needed, effective, and appropriate care. This is related to accessibility—that is, whether people get the proper preventive, diagnostic, or therapeutic services; whether they delay seeking care; and whether they receive appropriate recommendations and referrals for care. People may face geographic, administrative, cultural, attitudinal, or other barriers that limit their abilities to seek or receive such care. Within managed care environments, efforts to restrict access to some services may result in underuse of care.

-

Shortcomings in technical and interpersonal aspects of care. Technical quality refers to the ways health care is delivered—e.g., skill and knowledge in making correct diagnoses, and prescribing appropriate medications. Professional

-

competence is critical to high quality care, and inferior care results when health care professionals are not competent in their clinical areas. Interpersonal aspects of care are of particular importance in primary care. They include listening, answering questions, giving information, and eliciting and including patient (and family) preferences in decisionmaking. Interpersonal skills are also essential to primary care clinicians in their roles as coordinators—as members of a collaborative team and with other health professionals. The performance of systems must also be measured and improved. Indeed, greater attention will need to be focused on the failures of systems of care in which well-trained and well-meaning clinicians work.

The appropriate unit of assessment. To assess important attributes of primary care such as continuity, coordination, and the outcomes of and satisfaction with primary care, the appropriate unit is the episode of care whose beginning and ending points are determined, in principle, by the individual. An episode of care refers to all the care provided for a patient for a discrete illness. A particular episode of care begins when a patient brings a problem to the attention of a clinician (or when a clinician brings a problem to the attention of a patient), and that patient accepts the continuing care that may be offered (should it be needed). Because the beginning and ending points of an episode of care are defined in practice by a patient, the use of episodes of care to assess quality explicitly incorporates the patient's perspective whether those episodes last for a visit or two, for a year, or over a patient's lifetime. This means that structures for accountability must be able to measure episodes of care.

A change in focus from individual patients and clinicians to health plans and populations has other implications for quality measurement. The creation of reliable, uniform data systems and the collection of consistent data from a variety of sources means that quality assessment may become less dependent on review of individual cases. This changing unit of analysis from individual patients and clinicians to the performance of health plans might also result in less attention being paid to changes in the patient-clinician relationship. As policymakers shift attention toward systems of care, integration, and team approaches to health care delivery, it will be especially important to understand the relative risks and benefits to health outcomes and patient satisfaction of promoting or disrupting personal relationships.

Patient Satisfaction

An emphasis on satisfaction and information highlights the importance of patients' and society's preferences and values and implies that they should be elicited (or acknowledged) and taken into account in health care decisionmaking

(IOM, 1990). Knowledge about patient and family experiences in the health care system can be derived from patient reports—interviews and surveys of patients about their care. Patient reports on satisfaction can tell much about patient experiences in terms of access to and coordination of care, interpersonal and technical aspects of care, and understanding of instructions and follow-up advice. Although difficult to quantify, the “art of care” may influence outcomes of care, including satisfaction. The art of care includes clinicians' responsiveness to patient needs, their ability to elicit information about preferences for treatment alternatives, and generally their caring attitude.

Efficiency

In common parlance, efficiency is related to the organization and delivery of services so that waste and cost are minimized. Underuse of needed services (such as tests, therapies, or assistance) or overuse of services that result in unwarranted interventions or exposure to harm can hurt patients and waste resources—the time of patients and clinicians, their money, and access for other patients. Tests that must be repeated because results are lost or wrong are examples of inefficiency that are quality of care problems. Good primary care presupposes a careful effort to manage care to ensure the efficient use of resources including the effective use of other health and social services.

Ethical Behavior

Another form of accountability in primary care concerns the ethical behavior and decisionmaking by primary health care clinicians in relation to their patients, the community, and the health systems in which they practice. Primary care clinicians are responsible for care that respects and protects the dignity of patients and ensures that an individual's presenting complaint is dealt with or taken care of. Although the issues are not unique to primary care, clinicians need to be competent in managing events with significant ethical overtones, such as informed consent and advance directives, avoidance of conflicts of interest in financial arrangements, care of family members when goals are in conflict, reproductive decisionmaking and genetic counseling, privacy and confidentiality, and equitable distribution of resources. Primary care clinicians are accountable for their advice to and care of patients when they have financial or other incentives to use or not use certain resources.

Accountability of Patients

The committee acknowledges another aspect of accountability: that of the patient. Patients are responsible for their own health to the extent that they are capable—that is, that they have the knowledge and skills that allow them to participate in improving their health. Patients must also be responsible in their use of resources when they need health care. These issues go well beyond the committee 's purposes in this definition-oriented interim report, however, and will be explored more fully in the final report.