2

Problem Identification

Will the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program be able to identify problems well enough and early enough to be useful in relation to the goals of the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS)? Will the program be able to develop information to determine which trust resources are deteriorating or improving on a national, regional, or local scale? What criteria will be used to evaluate the condition of resources and to decide whether they are improving or becoming degraded? These questions are addressed in this chapter.

HOW DOES THE PROGRAM ADDRESS PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION?

As discussed in Chapter 1, the program's detailed plan (FWS, 1993) calls for four sampling networks:

-

Identification of specific contaminant problems on FWS trust lands, applying the protocol in the 1993 operations manual (Rope and Breckenridge, 1993) at the local level.

-

Determination of magnitudes of exposure and response to contaminants that affect key trust species at the regional level.

-

Determination of the status and trends of contaminant impacts on FWS trust lands within a sampling network consisting of a combination of ecoregions, habitats, and hydrologic units.

-

Determination of the status and trends of contaminant impacts on the habitats of key species at the regional and national level.

The first two are the problem-identification portion of the sampling network. The second two are the status-and-trends portion of the sampling network. Figure 1-1 illustrates these components.

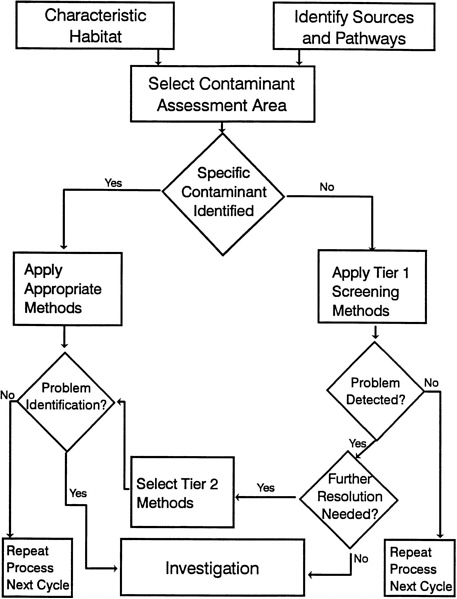

Sampling will involve all ecosystem levels (local, regional, national) and multiple lines of evidence based on analytical chemistry, bioassays and toxicity tests, biological markers, and indicators of population and community status or condition. Sampling will involve a hierarchical (tiered) approach to the intensity of sampling as illustrated in Figure 2-1.

According to the detailed plan, data generated by the program will be entered into the Contaminant Information Management and Analysis System (CIMAS), which is to be developed for this purpose. CIMAS will be supported by a geographic information system (GIS). Substantial interagency coordination, especially with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Environmental Monitoring and Assessment Program and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) National Water Quality Assessment Program, is expected to provide compatibility among databases.

WILL THE PROGRAM BE ABLE TO IDENTIFY PROBLEMS WELL ENOUGH AND EARLY ENOUGH TO BE USEFUL IN RELATION TO THE GOALS OF FWS?

Several general issues are involved in evaluating the adequacy of the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program to identify existing and emerging problems on trust lands and in trust species. The first is the definition of the specific populations, communities, and ecosystems to be monitored and evaluated. Different spatial scales on which problems will be identified (e.g., individual refuge versus a trust species' habitat) must also be distinguished. The rationale for selecting indicators and methods for detecting existing and emerging problems must be assessed. Finally, information must be integrated in a manner that allows decisive and effective management actions to be taken.

Identifying Problems

Throughout the analysis, it is important to remember that the program consists of the dual tasks of short-time diagnostic needs to address immediate problems quickly and long-term diagnostic modeling to prevent future problems. As currently defined, the program deals only with toxic substances and only with trust lands and trust-species habitats. As suggested by Table 2-1, the committee believes that FWS cannot escape dealing to some extent with other stresses that affect trust lands and trust resources.

Few biological responses are unambiguously attributable to toxic chemicals in environmental toxicology. The effects of toxic substances on trust resources cannot be evaluated without consideration of other natural and anthropogenic influences (there is additional discussion of this in Chapter 3). Toxic substances are not the cause of all observed adverse trends in resource condition. Information on such stressors as nutrient enrichment, habitat alteration, nonnative-species invasion, and overuse of trust lands and other resources is needed to identify adverse conditions that most likely are not related to toxic substances.

Table 2-1: Adequacy of Status-and-Trends Monitoring for Different Land-Ownership Categories

Issues of Scale

Monitoring and assessment approaches that are practical on the scale of a local refuge might be impractical on the scale of a region or an entire nation. Orians (1981) pointed out the problems associated with scaling and suggested why more attention should be paid to issues of scale. At least three aspects of the scale problem are relevant to the program. First, the spatial heterogeneity of any region increases as its size is increased. Designing a sampling scheme to

encompass all FWS lands is more complex than designing a scheme for a single refuge; the complexity becomes even greater if non-FWS lands (e.g., rangelands managed by BLM and land in national parks) are included. Second, the types and causes of variability in ecosystems differ on different scales. On the scale of an individual region, the most important influence might be caused by short-term, local phenomena, such as annual rainfall variation and local pollutant discharges. On regional and national scales, local variation tends to average out, and the important causes of variability are likely to be long-term climate changes and large-scale pollutant inputs (e.g., acid deposition and atmospheric transport of mercury and PCBs). Third, the cost of implementing a monitoring scheme is directly proportional to the number of samples collected. It is not economically feasible to sample with the same intensity (as to types of samples, spatial distribution of samples, and temporal frequency of sampling) for a regional or national problem as for a refuge-specific problem. The program cannot be effectively implemented beyond single refuges without consideration of these scaling issues.

The process of identifying local contaminant problems is the only aspect of the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program that has been developed in detail. Hazard identification will be performed on the local level because each refuge will probably have a unique array of contaminant issues. Sampling will be biased toward sites where contaminant impacts are believed to exist; this is reasonable and cost-effective, given the focus of identifying specific contaminant problems and locations on each refuge. It would be technically feasible to develop a region-based classification of trust-species habitats and to use it to develop sampling strata for a contaminant-effects monitoring program. However, implementing such a scheme would require cooperation and resource commitments from other organizations to collect data consistent with the program's detailed plan; no such agreements exist.

Proposed Indicators and Methods on Trust Lands

The difficulty with using a local-scale observation technique is that such a screening program is not truly predictive, because it is incapable of identifying problems before they emerge. In addition, the program has not yet developed a training method for the volunteers or field personnel who will identify potential problems. But the process is capable of categorizing the severity of emerging problems before they become crises.

Four categories of environmental indicators (results of analytical chemistry, results of bioassays and toxicity tests, indicators of organism health, and population and community indicators) will be used to detect contaminant problems on refuge lands. This approach, which attempts to integrate multiple lines of evidence of environmental damage, recognizes that no type of indicator is best suited for all monitoring purposes. A reliance on multiple lines of evidence offers the potential for a more reliable assessment of habitat condition than do many previous monitoring programs.

The ecological indicators identified in the detailed plan are heavily biased toward wetland and aquatic ecosystems. Some refuges have considerable amounts of upland habitat that is important for the maintenance of populations of trust species and other key species. Thus,

additional ecological indicators beyond wetland and aquatic ecosystems applicable to terrestrial habitats seem warranted.

A hierarchical or tiered approach is proposed to maximize the cost effectiveness of the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program. Tier 1 methods have been selected to provide a general screening to identify sites with potential contaminant problems. More intensive sampling would follow at such sites to confirm the existence of contaminant impacts and to suggest causes. Methods used for this purpose (Tier 2) must be diagnostic for a specific contaminant or trust species. Diagnostic methods are more limited in their scope of use and are often more expensive to perform than the screening methods in Tier 1.

Conceptually, the tiered approach is logical and follows from similar developments in the field of ecotoxicology. However, the proposed classification scheme fails to recognize that categories of indicators are not equally suitable as screening and diagnostic indicators. Community-level indicators sometimes provide useful assessments of ecological condition (and are good Tier 1 indicators) but are generally not very diagnostic (and are poor Tier 2 indicators). For example, fish and benthic macroinvertebrate community indexes are sometimes used by regulatory agencies as indicators of pollutant impacts on aquatic ecosystems. There is no reason why all four categories of indicators must always be used in both tiers. The categories of indicators proposed all include a wide variety of methods, so multiple independent lines of evidence can come from one category, as well as from different categories.

Ability to Detect Emerging Problems

The early-warning capability of past monitoring programs has typically been low because sampling focused principally on the biological end points of interest, e.g., populations of environmental or economic interest. A more effective approach to environmental management is to take action before attributes of interest have been affected. This sort of management requires the use of early-warning indicators, changes that are related directly to attributes of interest. Early-warning signals of environmental deterioration include increases in the concentration of a toxic chemical above that known to elicit an unacceptable response in trust species or other key species, changes in physiological indicators that are related to organism and population status, and changes in populations and communities of organisms that have short life cycles. Although systematic monitoring is necessary for documenting contaminant-related problems, observations by refuge personnel that spend time on trust land observing trust species are critical for successful problem identification. Historically, problems have usually been identified by people in the field. Good observations can identify new problems and document variability and long-term trends.

Information Integration and Use in Decision-Making

Making a determination that a habitat has suffered an impact and that remediation is warranted requires an appropriate benchmark or control for comparison and a threshold for action. The Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program proposes the use of reference sites for comparison and ecological action levels (EALs) for decision-making.

Site selection and comparison procedures need to be discussed in greater detail. Comparison of the magnitude of an indicator between reference and affected sites is an important part of the data-interpretation process (p. 76 of the detailed plan). It is important that reference sites be similar to affected sites in all respects except the presence of the contaminant of interest. Rarely is it possible to find such comparable sites, nor is it likely that two identical reference sites will be found. Therefore, when one is estimating the degree of difference between reference and affected sites, it is essential that an estimate of background variability among reference sites be included. The magnitude of background variability will determine the sample size (i.e., number of sites) required to show that a particular deviation from the nominal condition is statistically significant.

Ecological Action Levels

Decision-making in the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program will be driven by EALs. These thresholds will be based on available water-quality criteria and biological effects. As ecological information is accumulated both within and outside FWS, EALs will be developed over time to determine the magnitude of contaminant problems and to develop site-specific remediation plans (p. 78 of the detailed plan).

The process for developing EALs for different indicators requires a research program that is not included in the detailed plan. It appears that management decisions at the refuge level will be based largely on EALs. However, the process by which EALs will be determined is not specified. It might be appropriate to derive EALs for specific contaminants from existing water-quality criteria, but available databases on biological-effect thresholds are not suited to FWS purposes. Some state and federal criteria for population and community thresholds (e.g., changes in diversity index) have little scientific usefulness because of their subjective nature.

The development of thresholds that correspond with specific magnitudes of ecological change is difficult. However, because of the importance of these thresholds to the program, the revised detailed plan should specify ways to use existing and developing databases to derive EALs for different types of indicators in a scientifically defensible manner. As EALs are derived, they should be subjected to outside peer review; for reasons of credibility, it is not sufficient that EALs only be “internally consistent.” It should be determined in advance how often EALs will be revised and how changes in EALs will affect decisions based on past screening efforts.

Collecting and Analyzing the Data

Several aspects of the proposed sampling design are inadequate. There is virtually no discussion in the detailed plan or the operations manual about suitable experimental designs and statistical procedures for testing hypotheses. Sampling must be designed to allow statistical comparisons to be made among sites with a known level of statistical power. Data collection should be designed to test specific hypotheses concerning exposure-response relationships. The detailed plan provides no rationale for selecting specific indicators at different sites or for integrating information from different indicators. The operations manual proposes the development of unambiguous, site-specific monitoring objectives that would drive data-collection efforts. These monitoring objectives would be developed on the basis of results of the initial ecological characterization of a refuge and could serve as the basis for the formulation of falsifiable hypotheses. This process must be included in the revised detailed plan.

The proposed screening process will require the collection and analysis of large amounts of data at each refuge. The use of personnel for qualitative and quantitative assessment of environmental change and problem identification has not been developed in the screening process. Evaluation of observation and screening data by and from these personnel needs to be part of the program. At some point, costs must be considered, i.e., whether available funding will support the proposed level of sampling efforts. Thus, cost is another reason for adopting a phased approach, and the question of cost suggests why it is important to depend on people in the field for problem-identification screening. Observations by these personnel of qualitative and quantitative change in processes, habitat, and species are important to establish short-term and long-term trends.

The program will need both short-term and long-term diagnostic modeling to identify problems. This aspect is addressed primarily in Chapter 3 in the subsection on models. However, it is also important to mention here that scientifically sound models of the flows of anthropogenic contaminants through the known pathways of ecosystems are needed to link with the causality models described in Chapter 3. The program also needs to consider both the short-and long-term uses of its data and the integration of these models.

Problem Identification for Trust Species

The rationale for this program component is that FWS has a legal mandate to protect species listed under the Endangered Species and Migratory Bird Treaty Act throughout their geographic ranges, not just on FWS lands. This emphasizes the need, as discussed earlier, for a region-based approach. In these cases, several types of ecosystems need to be evaluated for a representative species. The trust-species component of the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program proposes to select specific “key” trust species representative of the full range of species included in the FWS mandate and to monitor the exposures and responses of these species to toxic substances throughout their ranges.

Criteria for key-species selection are provided on pp. 28-29 of the detailed plan, but no details concerning the information to be collected are provided in the document. It might be

presumed that relevant information would be of the same kinds as collected in the refuge-specific problem-identification component: exposure estimates derived from information on environmental contamination of soil, air, and water; toxicity-test data on the key species or surrogate species; body-burden estimates and biological-marker data; and population characteristics (growth rates, age and size distributions, and sex ratios).

The detailed plan identifies trust species as a focus of the program; however, which trust species or how monitoring will be achieved is vague. More information and development are needed.

WILL THE PROGRAM BE ABLE TO DEVELOP INFORMATION TO DETERMINE WHICH TRUST RESOURCES ARE DETERIORATING OR IMPROVING ON A NATIONAL, REGIONAL, OR LOCAL SCALE?

Two components of the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program deal with status and trends of FWS trust lands and status and trends of key-species habitats. The rationale for the FWS trust-lands component is provided on p. 25 of the detailed plan:

Statistically sound assessments of the contaminant condition and changes in this condition on Service lands will help identify emerging contaminant issues and provide quantitative measures with known confidence levels for distinguishing contaminant-associated change from natural fluctuations.

The trust-lands component was included as a separate program element because data collected from the problem-identification component are inherently biased by their emphasis on lands known or thought to be affected by contaminants.

A rationale for the status and trends of key-species habitats component of the program is provided on p. 30 of the draft detailed plan:

To adequately evaluate the hazards that contaminants pose to trust species, habitats that support them must also be evaluated. For some classes of contaminants, the only way to prevent or measure effects is to focus on habitat instead of the organism. Degradation of habitat by contaminants can have dramatic impacts on biota and may be observable before adverse effects on populations of Trust species.

This component is expected to use the same “key species” used for the component related to exposure and response of trust species. Habitats for the key species will be defined, mapped, and stratified and then sampled randomly with selected Tier 1 measures.

The following pages evaluate the status-and-trends programs in terms of each of the program elements.

Table 2-2 summarizes the possible status-and-trends components in the program defined on the scales of trust lands, trust-species habitats, and all DOI lands. Biological properties—such as biodiversity, ecological processes (e.g., primary production and nutrient cycling), and habitat structure (Table 2-2)—are important aspects of ecosystem sustainability and ultimately determine the ability of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems to support trust resources on FWS-managed refuges. Both structural and functional aspects of ecosystems vary with time as a result of natural processes and have been greatly modified by other human activities besides the production of toxic substances. Human processes now dominate many landscapes, and that makes determination of relationships among processes increasingly complex. To provide useful information on impacts of toxic substances, the program must be able to distinguish between natural and human-induced sources of variability and between variability due to contaminants and other human impacts.

As illustrated in Table 2-2, the committee concludes that, rather than just trust resources, which are the sole focus of the detailed plan as defined by FWS, impacts of toxic substances on biodiversity, ecological processes, and habitat changes are equally important and should be addressed by the program's problem-identification component. In general, the committee concludes that the status and trends component is conceptually inadequate for ecological processes, such as primary production and nutrient cycling that cannot be measured by investigating single species, and for most species that are not specifically managed by FWS.

As Table 2-2 suggests, the committee believes that the status-and-trends components of the program will be much easier to implement for FWS's existing wildlife-refuge system than for habitats of wide-ranging trust species. Moreover, if the program were expanded to include other lands managed by DOI, new habitat classifications and new suites of indicators would be required.

Status and Trends on Trust Lands

The trust-lands component is to be a stratified random-sampling scheme that will provide regional and national assessments of the contaminant condition of FWS lands and statistically sound analyses to distinguish contaminant-induced changes from natural fluctuations. Condition measures are to be drawn from the same lines of evidence used in the problem-identification component: analytical chemistry, toxicity tests, biological markers, and community structure-function relationships.

Measures of successful implementation of this component include categorization of all FWS lands into consistent and mutually exclusive ecogeographical groups; detection of problems and environmental changes at early stages; selection of groups of indicator variables based on relevance, sensitivity to contaminants, and relationship to hypothesized contaminant-related impacts; development of a decision framework for use in determining actions to be taken when adverse conditions are identified; and data-quality objectives for the suite of indicators selected.

Table 2-2: Adequacy of the Program's Proposed Problem Identification for Different Land Ownership Categories

This table describes how well the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program addresses problem identification for different land-ownership categories. “FWS trust lands” are owned by the federal government and managed by FWS. “Trust-species habitats” are lands occupied by species or ecosystem types for which FWS has management responsibility, regardless of land ownership. “All DOI lands” are lands owned by the federal government and managed by any agency within DOI. Column 1 indicates possible issues that the problem-identification component either is now addressing or could be addressing. Columns 2, 3, and 4 indicate the committee' s judgment about how well the program can address these issues for different land-ownership categories. The shaded blocks provide advice on areas that are not currently addressed by the program but that might be addressed in the future by the NBS.

|

The critical issues of variable selection and statistical design are hardly addressed in the detailed plan. As noted above, the Tier 1 measures are not clearly distinguished from the Tier 2 measures. Costs and sampling variability differ greatly between the different types of measures. Moreover, there is no validly comparable set of biological indicators that can be applied regionally or nationally. The committee does not believe that it is appropriate to use a comprehensive suite of indicators developed for site-specific application as part of a regional or national program. Research is needed to develop a small number of useful, inexpensive indicators that would serve regional and national evaluation purposes and that can be used for more intensive data collection if problems are found. The specific kinds of followup on data to be obtained can be determined from the pattern of adverse conditions detected and specific a priori hypotheses concerning patterns of change that are expected to be caused by toxic substances.

Status and Trends of Key-Species Habitats

This component is subject to the same problems as the trust-lands component with respect to indicator selection, sampling design, etc. However, because of its broad scale, it is not clear that the problems are tractable at all. Many of the trust-species habitats are on non-FWS, non-DOI, and even non-U.S. land. It is clear from the plan and from presentations made by FWS staff at the committee's meetings that external partners will be relied on for some part of the data to be included in this component. Statistical rigor and appropriate survey design are required to detect trends “with known confidence ” and to “distinguish contaminant-induced changes from natural fluctuations, ” as now suggested in the plan. Furthermore, data currently being collected by potential partners might even be unsuitable for the needs of the program. The draft detailed plan does not evaluate the utility of the data being collected by these partners. There is a need to develop agreements with them.

Presumably, random sampling of key-species habitats over the full range occupied by the species would be required to assess overall species condition and exposures. Contaminant-exposure and biological-effects data would need to be coordinated and collected with consistent sampling protocols on large spatiotemporal scales. The committee is not aware of any monitoring programs that collect exposure and effects information on this scale. The Great Lakes Herring Gull Program is in many ways similar to the trust-species component of the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program, but the former's objectives are much more tightly focused than the latter's. The Great Lakes Herring Gull Program was implemented after a problem was detected, and it is used to monitor changes in toxic chemicals in the environment; this is different from what the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program proposes-broad-scale monitoring not related to hypothesis-testing.

A more circumscribed approach focusing on well-defined populations that occupy restricted ranges might be feasible. A national program focusing on a few well-selected biological indicators indicative of contaminant exposure would be feasible and within the scope of the current National Contaminant Biomonitoring Program. It is not possible to assess every impact on every trust species or habitat; hence, a matrix should be developed to determine how

priorities and limited resources can be used most effectively in a hypothesis-testing framework. Positive evidence of exposure could trigger more detailed studies involving a wider range of indicators but a more restricted suite of species and geographic ranges.

CONCLUSIONS

The biological-assessment approach as described for the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program should be an important tool for examining the extent of toxic-substance problems with FWS trust resources. In addition, the success of management or policy changes in mitigating or reversing toxic-substance problems on the local, regional, or national scale could be tested by the program. However, broad-based monitoring and measurement cannot be substituted for direct field assessments and hypothesis-testing. The fundamental core of the program must be on-site observations to develop and test a hypothesis. Several biologically based federal monitoring programs already exist. Although sharing of data and coordination of efforts might strengthen all programs, the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program should be grounded in hypothesis-testing and analysis of how policy modifications influence toxic substances on trust resources.

In principle, the program should be adequate for identifying local contaminant problems on FWS lands. However, several methodological questions remain unanswered, and many of the proposed screening procedures will undoubtedly need to be refined. As written, the detailed plan provides little basis for evaluating their efficacy. Evaluation would be based on the operations manual referred to in the detailed plan. 13

The draft detailed plan and operations manual discuss critical issues of study design, including selection of indicators, analytical methods, evaluation of toxicity data, and statistical design, but specific decisions about these issues are left to “professional judgment” by refuge technical staff. Most FWS field staff do not have the training or technical support needed to make such judgments.

Given the above problems, the phased approach to implementation of the program should be continued. Many of the screening procedures appear marginally developed or untested. Current pilot studies have focused principally on the evaluation of sampling techniques and not on hypothesis-testing. Additional studies are required to evaluate site-selection procedures, hypothesis development, candidate indicators, and data-analysis procedures. Phasing should proceed in such a way that the results of previous pilot studies are used to refine methods to be used in later studies and to streamline and develop cost-effective sampling protocols.

The committee concludes that the trust-species exposure-response component of the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program should not be implemented now. Partnerships with other organizations could be sought to provide information outlined in the plan, but it would be more feasible and cost-effective to expand the current National

|

13 |

The committee reviewed the operations manual as originally written by the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory (INEL), not as later modified by the NBS, because it was not provided to the committee until after deliberations were completed. |

Contaminant Biomonitoring Program to include a broader range of contaminant exposure and effect indicators.

The committee concludes that a status-and-trends program is worth while and should be designed and implemented for the FWS lands and trust species but that such a program should be part of a broader environmental framework administered by the NBS and involving the broad partnership of federal, state, and local organizations, as described in the National Research Council's proposal for the NBS (NRC, 1993).

The committee concludes that the component of the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status an Trends Program concerning status and trends on trust lands as proposed in the draft detailed plan is not viable because

-

Problem detection relies on massive sampling.

-

Some of the measures proposed cannot be usefully defined on a regional or national scale.

-

A cost-effective status-and-trends component will require much greater attention to statistical design, program management, and coordination with other environmental monitoring programs than has been demonstrated in the current plan for the program.

If this component is to be retained, a detailed plan must be developed that includes the following:

-

Hypotheses or conceptual models that link specific types of contaminant exposures to adverse changes in exposed species or ecosystem types.

-

The habitat-classification scheme that will be used to stratify the sampling program.

-

Explicit statistical criteria for determining acceptable confidence intervals for status measurements and trend detection.

-

The supporting information (e.g., results of toxicity tests and use of biological markers) needed to test hypotheses concerning the causes of adverse changes.

Before full program implementation, pilot studies of each of the above plan components must be performed to confirm their technical feasibility and to develop implementation-cost estimates.

All the above requirements apply equally to the component concerning status and trends of key-species habitats; for this component, however, the issue of data required from potential partners is of overriding importance and must be addressed before any pilot studies are undertaken. The component must identify specific measurements and statistical design criteria for data to be obtained from potential partners. The data actually being collected from potential partners must then be matched against these specifications.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 2-1: A more general procedure should be developed for detecting problems affecting FWS trust resources through and observations by volunteers, nongovernment organizations, and field personnel. The program should be directed toward characterization of existing conditions, natural biological variability, and the effects of human perturbations.

Recommendation 2-2: The tiered bioassessment indicator scheme used to assess the presence and affects of toxic substances on trust resources should be revised to distinguish clearly between general-condition indicators (Tier 1) and diagnostic indicators (Tier 2).

Recommendation 2-3: Suitable indicators should be developed for trust resources other than wetlands or aquatic ecosystems, such as uplands.

Recommendation 2-4: The draft detailed plan should be revised to incorporate sound monitoring-program design principles, including

-

Testing of specific hypotheses regarding contaminant exposures and effects.

-

Defining and characterizing of reference sites.

-

Developing statistical-power criteria for determining sample sizes, spatial sampling intensities, and temporal sampling frequencies.

-

Specifying statistical methods.

Recommendation 2-5: The Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program should be implemented through a phased approach that thoroughly tests all aspects of the program at a few sites before adding new sites.

Recommendation 2-6: A rigorous research program should be implemented for development and validation of ecological action levels of biological indicators, such as biochemical markers and population and community indexes.

Recommendation 2-7: A support infrastructure should be developed that will provide FWS personnel with training in critical study-design issues—such as indicator selection, analytical-methods selection, toxicity-data evaluation, and statistical design—and offer specialized technical support to refuge managers charged with implementing the program.

Recommendation 2-8: The current National Contaminant Biomonitoring Program should be upgraded to include a broad range of contaminant-exposure and -effect indicators, which should then be folded into the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program.

Recommendation 2-9: A detailed sampling network plan for the status and trends of contaminants on trust lands should be developed, as outlined in this report. In particular, the plan should describe the habitat-classification scheme used to stratify the sampling program, the

specific measures of resource condition to be used, and the criteria to be used to distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable resource conditions.

Recommendation 2-10: Before full implementation, pilot studies of all program components should be conducted to confirm technical feasibility and to develop implementation-cost estimates.

Recommendation 2-11: Before implementation of the sampling network for the status and trends of key-species habitats, specific measurements and statistical-design criteria for data to be obtained from partners should be identified. Implementation should proceed only if partners are willing to provide data according to specifications provided to them by the Biomonitoring of Environmental Status and Trends Program.

Recommendation 2-12: The program needs to integrate its data collection so that both short- and long-term diagnostic needs can be addressed.