3

Analysis of Effectiveness of Past Efforts to Build Geriatrics

INCREASE IN NUMBER OF GERIATRICIANS

As reported in Table 1, the number of certified geriatricians in internal medicine, family medicine, and geriatric psychiatry continues to rise. Nevertheless, several important trends must be noted. First, in internal medicine and family practice, the number of geriatricians who have been certified has increased at a steady rather than an increasing rate over the last two examinations. Whether a sharp increase will occur in 1994, the last year for which admission to geriatric medicine certification under the practice pathway is available, remains to be determined. Second, the number of geriatricians who have received formal training has remained relatively constant at each biennial examination. This number is quite close to the number of trainees in geriatric fellowship programs that would be expected to graduate over a 2-year period. These figures suggest that, given the current training levels, a steady state of approximately 200 physicians with formal training in geriatric medicine will be taking the examination every 2 years. This is far short of the recommendations made by the Institute of Medicine (Institute of Medicine, 1987).

Although the current number of certified geriatricians (6,784) exceeds the recently projected needs for the number of geriatricians who will be needed to provide clinical care for older people under all scenarios except for steady economic growth (Reuben et al., 1993b), certification in geriatrics is limited by time. Accordingly, physicians who became certified in 1988 and 1990 will have to be recertified within the next few years. The vast majority of these geriatricians were not trained on fellowships and many of them are older physicians (Reuben and Robertson, 1987). By the year 2000, a number of these geriatricians will have retired, and it is likely that others will have decided not to renew their certifications. Therefore, the actual number of geriatricians may fall by the end of the decade.

INCREASE IN NUMBER OF GERIATRICS FACULTY

Accurate information on the historical and current supply of geriatrics faculty has been difficult to obtain. The results of an accreditation survey by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) from 1991 to 1993 indicated that there were 621 faculty members nationwide with primary responsibility for teaching geriatric medicine (LCME, unpublished data, 1993). From 1969 through 1989, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) recorded 215 faculty appointed in geriatric medicine. During that same time period, 36 faculty in geriatric medicine were recorded as being deactivated (Brooke Whiting, AAMC personal communication, 1993). In 1992, the AAMC faculty roster listed 42 family physician faculty members as having geriatrics as a specialty, 169 internist faculty as having geriatrics or geropsychiatry as a specialty, and 20 psychiatrists as having geriatrics as a specialty (Association of American Medical Colleges, 1992). Because of poor response rates and other factors, these figures are regarded in the geriatrics community as being quite low.

Additional insight may be obtained from a 1988 survey of geriatrics training in residency programs in family practice and internal medicine (Reuben et al., 1990b). In that survey a 33 percent random sample of programs was employed, and the response rate was 100 percent. Internal medicine residency programs reported an average of 2.8 full-time geriatrics faculty available, and family practice programs reported an average of 2.3 geriatrics faculty available. When extrapolated to include all programs, estimates of the number of full-time geriatrics faculty might be as high as 869 in family practice and 1,176 in internal medicine. Although that study examined only physician faculty who were teaching at the residency level, it is likely that many of these faculty were also teaching at other levels of medical education (e.g., undergraduate and fellowship levels). These figures may also be high, because it is possible that faculty could be teaching in more than one residency program or across specialty disciplines.

As part of a contract to the Health Resources Services Administration, the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), School of Medicine and RAND conducted a study of the adequacy of geriatrics faculty and surveyed geriatrics faculty. Survey results were adjusted for sampling and for response rate to provide national projections of the number of geriatrics faculty in U.S. medical schools and residency programs. The number of faculty was multiplied by an adjustment factor that was the ratio of the number of students (or residents) nationwide to the number of students (or residents) in schools (or programs) responding to the survey. That study estimated the following numbers of current geriatrics physician faculty at U.S. medical schools ( Table 3): internal medicine, 909; family practice, 574; neurology, 267; psychiatry, 438; and physical rehabilitation and rehabilitation, 86 (Reuben et al., 1993a).

TABLE 3 Geriatrics Faculty (M.D.s) Available and Currently Needed as Determined by Two Estimation Methods

|

Estimation Method |

Internal Medicine |

Family Practice |

Neurology |

Psychiatry |

Physical Medicine |

|

Method 1 (advisory panel) |

|||||

|

Minimum no. of faculty needed to sustain a divisiona |

2,407 |

1,866 |

867 |

1,143 |

558 |

|

No. of faculty available |

909 |

574 |

267 |

438 |

86 |

|

Faculty deficit (no.) |

1,498 |

1,292 |

600 |

705 |

472 |

|

Method 2 (teaching needs) |

|||||

|

No. of faculty needed (FTEs)b |

1,102 |

846 |

257 |

467 |

149 |

|

Current distributions of teaching between M.D.s and non-M.D.s (%) |

74 |

69.7 |

79 |

67.3 |

—c |

|

FTEs needed |

2.82 |

3.18 |

4.94 |

3.89 |

2.12 |

OUTCOMES OF MIDCAREER TRAINING PROGRAMS

From 1984 through 1988, The John A. Hartford Foundation supported 29 physicians in academic medicine who decided to redirect their careers toward geriatric medicine by participating in a 1-year midcareer faculty development program. Robbins (1993) recently reviewed the experiences of these trainees and found that 87 percent now spend a significant amount of their time training others in geriatrics. Fifty-eight percent published at least one peer-reviewed article as a result of work completed during their fellowship year. The most commonly related disadvantages to the program were the burden of relocation for a year, the lack of academic support after returning to their home institution, and the fact that a 1-year training period was too short (Robbins, 1993). The Bureau of Health Professions funded nine physicians in 1-year retraining programs from 1989 to 1992. All nine accepted faculty positions subsequent to completion of their faculty retraining program (Susan Klein, Bureau of Health Professions, personal communication, 1993).

INCREASE IN NUMBERS OF GERIATRICS FELLOWSHIP PROGRAMS

The number of geriatric fellowship training programs almost tripled from 1980 to 1987, from 36 in 1980 to 103 in 1987. A survey of geriatric fellowship programs done by investigators at UCLA revealed that 262.5 positions were available in geriatric medicine and geropsychiatry in the 1986 academic year, and 88 percent of these positions were filled (Vivell et al., 1987).

In 1988, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education began accrediting geriatric medicine fellowship programs in internal medicine and family practice. Initially, 62 internal medicine programs were accredited (as of July 1988). By January 1994, 84 geriatric medicine fellowships had been accredited by the Residency Review Committee in Internal Medicine. Initially, 16 family medicine programs were approved by the Residency Review Committee in Family Practice; this number rose to 17 by January 1994 (Karen Lambert, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Evaluation, personal communication, 1994). In addition, there are other nonaccredited programs in geriatric medicine. To date, there have been no accredited geriatrics psychiatry fellowship programs, although a process for accreditation was approved in September 1993. In other specialties of medicine, there is no process for accreditation of geriatric medicine programs.

The American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry has maintained an inventory of geriatric psychiatry fellowship programs. In 1992, the inventory listed 55 programs in 26 states and the District of Columbia. The majority of the programs (74 percent) were started in the 1980s. Assuming a maximum capacity of two positions per program per year and a minimum training duration of 1 year, the maximum capacity of the nation's geriatric psychiatry fellowship programs would be 106 board-eligible

fellows per year (Small et al., 1988; Jeffrey Foster, American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, personal communication, 1993).

The American Geriatrics Society published directories of geriatrics fellowship programs in 1987 and 1990 (as well as an update in 1993) that listed geriatrics programs in geriatric neurology, geriatric psychiatry, as well as accredited and unaccredited geriatric medicine fellowships in the United States and Canada. In 1987, the directory listed 125 fellowship programs, anticipated programs, and residency programs. By 1990, this number had risen to 145, and by 1993, 7 new fellowship programs had been added and 1 fellowship program had been discontinued (Melissa Silvestri, American Geriatrics Society, personal communication, 1993).

NUMBER OF UNFILLED FELLOWSHIPS SLOTS

Statistical information on graduate medical education in the United States is collected annually by the American Medical Association (AMA) Department of Directories and Publications. Information on the numbers of geriatric medicine fellowship positions that are filled has been available only since 1990. Only accredited programs are surveyed. Table 4 presents the number of positions offered, the number of positions filled, and the percentage of positions filled for the years 1990 –1992. Although there was a 17 percent rise in the number of geriatric medicine fellowship positions offered in internal medicine from 1990 to 1992, the percentage of positions filled declined over the 3-year period. In family practice, the number of geriatric medicine fellows remained constant over the 3 years, while the number of positions available increased by 52 percent.

These figures are particularly disappointing when they are compared with the trends in other fellowships in internal medicine (Table 4). Over the same 3-year period, cardiology fellowships have been overfilled twice, despite a 35 percent increase in the number of fellowship positions offered. The rates that pulmonary fellowships were filled was 96 percent or greater in each year, despite a 21 percent increase in the number of positions offered. In nephrology fellowships, the fill rates fluctuated over the 3-year period (between 75 percent and 94 percent), but the number of positions available increased 23 percent. Data from the National Study of Internal Medicine Manpower (NaSIMM) provide different figures but indicate similar trends. From 1981 to 1992, the number of cardiology fellows increased from 1,556 to 2,627, while the number of geriatric medicine fellows increased from 74 to 230. The increase in the number of cardiology fellows is due in large part to changes in the duration of training and the increased number of fellows in advanced years of fellowship training. Between 1976 and 1992, the number of first-year cardiology fellows increased by only 19 percent. Nevertheless, in 1992 the ratio of first-year cardiology fellows to first-year geriatrics fellows was 13.6:1 (Kohrman et al., in press).

TABLE 4 Geriatric Medicine, Cardiology, Pulmonary, and Nephrology Fellowship Positions Offered and Filled, 1990–1992a

|

1990 |

1991 |

1992 |

1993 |

|||||||

|

Discipline |

No. of Positions Offered |

No. of Positions Filled |

% Filled |

No. of Positions Offered |

No. of Positions Filled |

% Filled |

No. of Positions Offered |

No. of Positions Filled |

% Filled |

No. of Positions Offered |

|

Internal medicine (geriatrics) |

170 |

153 |

90 |

259 |

181 |

70 |

270 (180)b |

199 |

74 |

299 (142)b |

|

Family practice (geriatrics) |

31 |

15 |

48 |

49 |

17 |

35 |

47 (35) |

16 |

34 |

42 (21) |

|

Cardiology |

1,537 |

1,677 |

109 |

1,948 |

1,925 |

99 |

2,057 |

2,079 |

101 |

2,180 |

|

Pulmonary |

756 |

725 |

96 |

918 |

881 |

96 |

915 |

911 |

100 |

953 |

|

Nephrology |

470 |

417 |

88 |

639 |

482 |

75 |

580 |

544 |

94 |

614 |

|

a Includes all years of fellowship training. b Number of first-year positions is indicated in parentheses. For previous years, these numbers are unavailable. SOURCE: American Medical Association, Department of Directories and Publications. |

||||||||||

In addition to the less than optimal fill rates of geriatric medicine fellowships, the quality of applicants for these positions can be questioned. A 1992 survey of the Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs (ADGAP) indicated that among 46 program directors of academic programs in geriatric medicine who responded to this item, they considered only 46 percent of the applicants to be acceptable (Jerome Kowal, ADGAP, personal communication, 1993). The survey results also ranked “the lack of qualified applicants” (ranked by 16 percent of 70 responders) as the most important negative factor affecting the ability to attract trainees.

In 1991 and 1992, NaSIMM asked program directors to designate the factors important in planning the number of future fellowship positions (Kohrman et al., in press). The number of qualified applicants was mentioned by 86 percent of the program directors when planning geriatrics fellowships, whereas it was mentioned by 56 and 64 percent of directors when planning cardiology and pulmonary fellowships, respectively. Furthermore, when asked about their recent ability to attract more or fewer qualified applicants to their programs, 54 percent of geriatric fellowship program directors reported attracting fewer (34 percent) or significantly fewer (18 percent) qualified applicants. In contrast, 58 percent of cardiology, 67 percent of gastroenterology, and 50 percent of pulmonary fellowship program directors reported attracting more qualified applicants. Anecdotally, many geriatric fellowship program directors have indicated that their candidates for fellowship positions are not among the top graduates of internal medicine and family practice residency programs, so recruitment remains a major obstacle.

GERIATRICS IN RESIDENCY TRAINING

Although the number of established academic units offering geriatric residency training increased from 28 to 40 between 1979 and 1984, this was in sharp contrast to the 442 residency programs in internal medicine and the 380 programs in family practice that were accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (Vivell et al., 1987).

More recent insight into geriatrics education during residency training can be obtained from two surveys of medical education at this level conducted in the late 1980s. In 1988, Reuben et al. surveyed a random sample of 33 percent of all 378 family practice and 420 internal medicine training programs accredited in the United States. They found that 80 percent of the family practice programs, but only 36 percent of internal medicine programs, reported having curricula in geriatric medicine in place. In internal medicine 61 percent of the curricula were required, and in family practice 92 percent of the curricula were required. Current curricula in both specialties were, on average, approximately 5 weeks long, and about three fourths of the time was spent in clinical experience (Reuben et al., 1990b).

As part of a contract to the Bureau of Health Professions, Friedman and

colleagues (Trustees of Boston University, 1989) surveyed residency programs in 10 specialties in 1989. For six specialties (otolaryngology, orthopedic surgery, neurology, psychiatry, urology, and physical medicine and rehabilitation), a 100 percent sample of the training programs was used. For the remaining four specialties (obstetrics and gynecology, general surgery, family practice, and internal medicine) a random 50 percent sample was obtained because of the large number of training programs in these disciplines. The overall response rate to the survey was 72 percent and the range was from 61 to 83 percent. Training programs in only five specialties (internal medicine, family practice, neurology, psychiatry, and physical medicine and rehabilitation) offered specific geriatric medicine rotations for residents. The percentages of training programs that required a geriatric medicine rotation varied widely among the specialties. Fifty-five percent of family practice residency programs required a geriatric medicine rotation whereas only 2 percent of neurology residency programs did. Elective rotations in geriatric medicine were offered by up to one quarter of the training programs in the five specialties. In no specialty did more than half of the eligible residents take the elective. The study estimated that 62 percent of family practice residents, 26 percent of internal medicine residents, 17 percent of physical medicine and rehabilitation residents, 48 percent of psychiatry residents, and 3 percent of neurology residents had taken either a required or an elective rotation in geriatrics (Trustees of Boston University, 1989). The discrepancies between the 1988 and 1989 surveys conducted by UCLA and Boston University may be due to differences in sampling, the definition of a “required” rotation or curriculum, and the response rates.

NUMBER OF MEDICAL SCHOOLS WITH REQUIRED COURSES IN GERIATRICS OR GERONTOLOGY: CHANGE OVER TIME

In 1976, 2 U.S. medical schools required undergraduates to take courses in geriatrics or gerontology, and only 15 medical schools had separate educational programs in geriatrics or gerontology. By 1984, a UCLA survey reported that 54 percent of the departments of internal medicine, 30 percent of the departments of psychiatry, and 37 percent of the departments of family practice reported that they sponsored at least one clinical program in geriatric medicine (Vivell et al., 1985).

According to the 1988–1989 AAMC curriculum directory, only 13 medical schools required courses or clinical experiences in geriatrics or aging (Association of American Medical Colleges, 1988-1989). By the 1992–1993 academic year, only 9 of 142 schools (including Canadian medical schools) required a separate course (Brownell Anderson, AAMC, personal communication, 1993). The LCME reports somewhat different figures, indicating that 14 U.S. medical schools taught geriatrics as a separate required course (Joanne Schwartzberg, American Medical Association, personal communication, 1993). According to the LCME, 102 of 126 reporting medical schools also taught geriatrics as part of a required course (e.g., medicine

clerkship); AAMC data indicate that 121 of 142 schools (including Canadian schools) taught geriatrics as part of a required course during the 1992–1993 academic year. Although the information from these two sources is not in complete agreement, both sources concur that there have not been substantial changes in the geriatrics curriculum over the past several years.

The 1983 graduation questionnaire conducted by AAMC reported that 3.2 percent of the graduating class for that year had had clinical experience in geriatrics. In 1988, 3.5 percent of the graduating class reported having taken an elective in geriatrics, but this percentage declined from 1988 to 1993. Among 1992 graduates, only 2.9 percent had taken an elective in geriatrics (Wendy Colquitt, AAMC, personal communication, 1993).

STUDENT RESEARCH OR OTHER PARTICIPATION IN GERIATRICS

Since 1989, the John A. Hartford Foundation has been sponsoring summer student research projects under the auspices of its Academic Geriatric Recruitment Initiative awards. The number of students participating in summer research in geriatrics and aging and presenting the results of that research at American Geriatrics Society (AGS) annual meetings increased from 49 in 1990, to 55 in 1991, and to 82 in 1992 (Patricia Reineman, University of Michigan, personal communication, 1993).

Between 1985 and 1991, the Dana Foundation in collaboration with the American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR) supported 90 medical students in geriatrics experiences; these were usually of 1-month duration at Centers of Excellence. Under its medications program and in collaboration with AFAR, the John A. Hartford Foundation has supported 43 medical students in geriatric pharmacology projects.

From 1986 through 1992, the Boston University School of Medicine and AGS offered a Summer Institute in Geriatrics for medical students, who were usually in their third or fourth year of medical school. Except for 1987 and 1993, when the program was not offered, between 16 and 20 medical students participated each year. The total number of participants was 111. The number of applicants was quite variable from year to year. In 3 years (1986, 1988, and 1989), the number of applicants was more than twice the number of available positions. In the other years, the program did not fill the available slots. In 1993, however, 27 applicants applied for 20 positions, but the program lost its funding (Anita Landry, Boston University, personal communication, 1993).

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION

Continuing medical education programs are one main link in the transfer of new

knowledge about treatments and technology from the laboratory to community-based practices. The majority of practicing physicians, especially those whose formal training ended before 1985, has never been exposed to organized geriatric training in medical school or during residency training. A study conducted by UCLA found that continuing medical education programs in geriatrics were not reaching practitioners. It was estimated from a survey for 1984 and 1985 combined that no more than 8,000 physicians attended at least 1 day of continuing medical education devoted solely to geriatrics. This was of a total population of 450,000 patient-care physicians in the United States at that time (Vivell et al., 1989). In 1986 Schneider and Williams observed that only 1 percent of continuing medical education courses dealt with geriatric medicine, despite the development of much new information and clinical technology in the field.

Since 1984, the Bureau of Health Professions has provided geriatrics education to physicians through its Geriatric Education Centers program. From 1984 to 1990, 21,440 allopathic or osteopathic physicians participated in programs of fewer than 40 hours' duration, and 879 participated in training programs of 40 or more hours. Moreover, the rise in the number of participants has been steady, from 274 in 1984 to 9,087 in 1990 (for fewer than 40 hours of training). The number of enrollees in programs of 40 hours or more increased dramatically from 1984 (9 physicians) to 1987 (177 physicians) and has remained within a range of 177–225 since that time (Ann Kahl and Susan Klein, Bureau of Health Professions, personal communication, 1993).

The advent of the joint certification examination of the American Boards of Internal Medicine and Family Practice for the Certificate of Added Qualifications in Geriatric Medicine, and subsequently in Geropsychiatry, has led to a virtual blossoming of continuing medical education efforts in the field. The American Medical Association compiles a semiannual guide called Continuing Education Opportunities for Physicians. These guides are based on continuing medical education programs that are sent in for publication in the Journal of the American Medical Association's listings and are not a comprehensive inventory of courses. From September 1992 through August 1993, 29 courses in geriatrics were listed in the guides (American Medical Association Division of Continuing Medical Education, 1992, 1993).

OTHER MEASURES OF GROWTH IN GERIATRICS

Other measures of growth in geriatrics include increases in the number of people who attend the AGS annual meeting and an increase in the number of abstracts submitted to that meeting. In 1983, attendance at the AGS annual meeting was 200. By 1987, this number had risen to 709, and by 1992, 1,786 people attended the AGS annual meeting (Angie Legaspi, AGS personal communication, 1993). Similarly, Landefeld (1993) noted a rise in the number of abstracts submitted to the AGS

annual meeting from the early 1980s to the early 1990s. This came at a time when the overall number of submissions to the American Federation for Clinical Research, the American Society for Clinical Investigation, and the Association of American Physicians have fallen (Landefeld, 1993). Furthermore, sections on aging have been established for the spring meetings of the three societies, reflecting additional growth in research on aging.

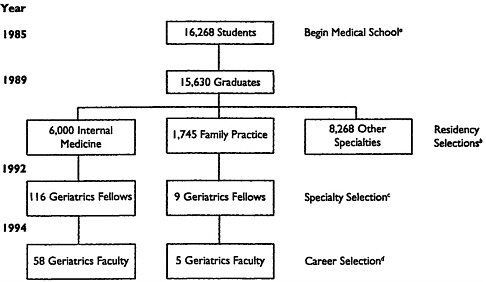

OBSTACLES AND CONSTRAINTS TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF ACADEMIC GERIATRICS

A number of studies have been conducted by UCLA and by the ADGAP over the past decade. Those have focused on the constraints in developing educational programs in geriatric medicine. While the emphasis on the various constraints that have been raised has changed over time and occasionally a new constraint has appeared, the constraints of a decade ago are still perceived to be the major obstacles to implementation of geriatric educational programs today. The most pressing obstacle impeding the development of academic programs in geriatrics appears to be recruitment into the field and the consequent lack of adequate numbers of faculty. As noted above, the ADGAP survey identified the lack of qualified applicants as the most frequently mentioned factor that negatively affects recruitment. A striking demonstration of the problem is presented by following the cohort of students entering medical school in September 1985 (Figure 1). These students are now at the point when they could be completely first-year fellowships in geriatrics. As noted in Figure 1, 0.8 percent of entering medical students eventually select fellowships in geriatrics medicine. This figure is inflated because it also includes foreign medical graduates; on the basis of the results of the AAMC longitudinal tracking survey, only 0.2 percent of 1989 U.S. medical graduates began geriatrics fellowships in 1992 (Robert Haynes, AAMC personal communication, 1993). The 1991–1992 NaSIMM survey (Table 2) indicated that 37 percent of graduates of geriatrics programs went directly into full-time academic positions and another 15 percent continued their training (Kohrman et al., in press). On the basis of the assumption that half of the graduates of fellowship programs in geriatric medicine pursue academic careers, it is obvious that the field is able to attract only a very small number of physicians. To place the recruitment problem in perspective, one's chances of surviving stomach cancer for 5 years are 10 times greater than the chances of a beginning medical student entering academic geriatrics.

Traditionally, faculty in geriatric medicine are recruited from the primary care disciplines of internal medicine and family practice, where they were trained. Since 1981, the percentage of students who participate in the residency matching program and opt for internal medicine has fluctuated from a low of 34.6 percent (in 1981) to a high of 37.6 percent (in 1988). The most recent match (1993) identified 36.3 percent of participants entering internal medicine. Similarly, family practice has

FIGURE 1 Yield of faculty trained in geriatric medicine from the medical school class entering in 1985. The total number of residents (16,013) includes some foreign medical graduates and thus is greater than the number that graduated from U.S. medical schools in 1989 (15,630). SOURCES: aSection for Student Services, Association of American Medical Colleges; bNational Resident Matching Program; cAmerican Medical Association Department of Directories and Publications, adjusted to estimated number of first-year fellows on the basis of the continuation rate of 70 percent from the first to the second year (does not include geropsychiatry training) (Kohrman et al., 1989); and destimated from historical trends.

represented a fluctuating proportion of the match, ranging from 10.3 percent (in 1992) to 13.1 percent (in 1981). In 1993, 11.8 percent of those who participated in the matching program entered family practice (Association of American Medical Colleges, 1993; Paul Jolly, AAMC, personal communication, 1993). However, on the basis of the NaSIMM projections from 1989 to 1990, an estimated 60 percent of internal medicine graduates enter subspecialty training (Andersen et al., 1992). Furthermore, this trend toward increasing specialization has been progressive and substantial. In 1982, 36.1 percent of graduating medical students planned to practice a general specialty of family practice, general internal medicine, or general pediatrics. By 1992, this percentage had fallen steadily to 14.6 percent (Medical School Graduation Questionnaire, Section for Educational Research [Association of American Colleges, 1993]).

TABLE 5 Possible Reasons for the Decline in Interest in Internal Medicine

|

Financial Considerations Reaction to cost-containment strategiesa Lower income potentiala The Practice of Internal Medicine Difficult lifestylea The straggle against chronic diseasea Problem patientsa Medical Education The hospital-based medical clerkshipa Out-of-date residency programsa Distant faculty role models The threat of AIDS Desire to limit areas of competencea Lure of other specialtiesa |

|

a Indicates possible reasons for lack of interest in geriatric medicine. SOURCE: Schroeder, 1992. |

Schroeder (1992) has identified possible reasons for the decline in interest in internal medicine (Table 5). Many of these also apply to a lack of interest in geriatric medicine. Financial considerations may be a major factor. Data from the 1992 Medical School Graduation Questionnaire administered by the AAMC Section for Educational Research (Association of American Medical Colleges, 1993) indicate a mean educational debt of indebted graduates (80.5 percent of medical school graduates have some debt) of $55,859 overall and an indebtedness of $69,479 for those who graduated from private institutions. According to the 1989 Survey of Total Compensation of U.S. Physician Employees, geriatricians earned approximately $81,000 per year, the lowest paid specialty area (AHA News, 1990). Furthermore, as implemented, the Resource-Based Relative Value System does not recognize either the ages or the medical complexities of geriatric patients in its reimbursement scheme.

The perceived need for faculty in geriatric medicine has remained largely unchanged over the past decade, and it is clear that the need as perceived by medical schools and their affiliated institutions far exceeds the capacity of the system to train faculty in geriatric medicine. There is a general perception that the training of faculty in geriatric medicine has emerged as an important medical education and health policy priority.

Clinical training sites are a second limiting factor in the development of academic geriatrics (Vivell et al., 1987). From repeated surveys, they appear to be

insufficient in number and often inadequate in quality, although there appears to have been an improvement in quality over time. The training sites that have been identified have included geriatric evaluation units in hospitals or ambulatory care clinics, geropsychiatry units, nursing homes of adequate quality, and a whole host of other available clinical sites which are largely community based; nevertheless, there continues to be a paucity of training sites. The lack of appropriate training sites appears to be related to the reticence of many academic medical centers to take on additional peripheral responsibilities away from their immediate physical locations. In part, this reluctance may be due to the lack of profitability of these sites. For example, Part A Medicare graduate medical education funds do not reimburse hospitals for the time spent by residents in home care, office, and nursing home settings. It is also of note that the use of institutional long-term-care settings as teaching sites has clearly improved over the past decade, but it also appears that some educational programs may regard the nursing home clinical experience as a sufficient exposure to geriatric medicine. This is clearly incorrect since nursing home care is only a relatively small component of the field.

A third major obstacle limiting the development of academic geriatrics is the overcrowding of the medical education curriculum. This problem has consistently been reported as a highly important one whether it relates to the undergraduate curriculum or that of residency programs. Other worthy courses or disciplines compete for medical students ' time, and it is an important issue for the undergraduate curriculum. In addition, other factors which have contributed to the inadequate expansion of curricular time are quarrels among family practice, psychiatry and internal medicine over responsibilities for geriatric medicine curriculum development, debates over the necessity of special courses in geriatrics medicine, and limited financial resources. Not all medical schools have encountered these problems, and in some, they are felt much more keenly than in others. In terms of the core training in internal medicine and family practice, it is important that, given the current and projected amounts of time that family practitioners and internists devote to the primary care of older people, a process for setting new educational priorities in residency training be developed. There must also be a willingness to reduce the time spent in other clinical experiences or to eliminate certain other clinical experiences currently in the residency programs. Otherwise, residencies must be lengthened.

It is difficult to implement structural changes to increase geriatrics training in the undergraduate curriculum and residency programs in part because of the attitudes of deans and departmental chairs. Interestingly, in a survey carried out by UCLA, internal medicine faculty ranked the importance of geriatric training lower than family physician faculty did. Furthermore, within internal medicine, program directors and/or departmental chairs ranked geriatrics lower than geriatricians did (Reuben et al., 1990b).

A fourth obstacle is the poor levels of reimbursement for the clinical activities of faculty in geriatric medicine. The current evaluation and management Common Procedural Terminology codes allow approximately $115 (including copayment) for

a visit of high complexity with a new outpatient; a follow-up visit of moderate complexity (approximately 25 minutes) is reimbursed at a total rate of $55 for an established patient (Sheila Kopic, UCLA Medical Center, personal communication, 1993). Other insurance systems for younger patients (including capitated contracts) reimburse providers at far higher rates. Although there are no systematic data that support the view that the low levels of reimbursement for the care of the elderly patients may be an obstacle to adequate levels of recruitment into the field, there is a perception based on anecdotal evidence that the reimbursement issue is a major factor leading to the lack of attractiveness of geriatrics as a career track. This intensifies the shortage of faculty by two mechanisms: (1) inadequate recruitment into the field and (2) excessive use of faculty time to generate clinical income to bring faculty salaries to a level comparable to that of faculty in other disciplines.

Other obstacles in the academic environment that relate to the lack of attraction of geriatrics to faculty include the roles that academic geriatricians must assume. The rapid growth in numbers of programs in geriatric medicine must be tempered invariably by the fact that growth and quality may not be synonymous. There is evidence that many of the fellowship programs may not be of optimal quality; in a UCLA survey (1987), fewer than 15 percent of the programs at that time could be considered strong (Vivell et al., 1987). Weaker programs are less attractive to students at all levels, including the fellowship training level. Academic leaders in a field must have credibility in research, teaching, and clinical service or in a combination of these domains. In addition, those who have real credibility in research can only do the research if they are effective in acquiring extramural funding. However, in geriatric medicine other qualities of leadership have emerged. These include management and program development expertise and skills at relating with other academic departments and disciplines, and with community-based ambulatory care facilities, nursing homes, and other caregivers. These qualities, taken together with the complex medical needs of the elderly, may be more than one could expect to find in more than just a few extraordinary individuals. It suggests that the development of several types of leaders in geriatric medicine may be a more rational objective than what has been attempted to date.

Finally, the limited academic success of geriatricians as physician-scientists and clinical investigators has been an obstacle to the development of academic geriatrics. There is a convincing body of evidence that indicates that faculty must have been involved in extensive research training beyond that of the traditional 2-year fellowship for success in research. Data from several sources suggest that the median duration of research training lies between 3.5 and 4 or more years. Success in research is determined by a variety of criteria, including the ability to acquire independent funding through the investigator-initiated RO-1 award or comparable mechanisms (Oates, 1982).

Of note, other obstacles that were perceived to be major ones a decade ago—such as the lack of professional recognition in geriatrics—have now been solved and no longer appear to be major.