WORKING GROUP SUMMARIES

The conference featured six working groups. Each group focused on one of the following topics: gasoline; paint; ceramicware glazes; industrial and occupational health; food, water, and waste disposal; and techniques for improved lead surveillance and monitoring. Each working group was charged with identifying specific action steps that could be tailored by participants to regional, federal, or local needs, as required, to reduce human lead exposure in the hemisphere. The members of each working group met for six hours over a two-day period. The following statements summarize the deliberations and conclusions of the six groups.

WORKING GROUP I

GASOLINE

MODERATOR: JACOBO FINKELMAN*

RAPPORTEUR: ELLEN SILBERGELD**

Working group participants included representatives from government and the petroleum and other industries. The group summarized its deliberations according to the following construct:

|

What to do: |

Phase out lead in gasoline. |

|

How to do it: |

Restrict the use of lead by consensus regulation, while ensuring the appropriate supply of sufficient substitutes to meet octane requirements (without excess environmental impact). |

|

Who is to do it: |

Refining industry (private and public sector). Auto industry, by producing vehicles engineered to operate on unleaded fuels. Governments, by ensuring adequate inspection and maintenance and by providing subsidies for refining and price preferences for consumer purchasing of unleaded gasoline. Consumers, by demanding unleaded gasoline and avoiding misfueling with leaded gasolines. |

|

What incentives: |

“Supporting” refinery capacity, tax preference for unleaded gasoline, and subsidies for engine retrofit, if necessary. |

|

What additional benefits could accrue, and for whom: |

|

|

Improved public image for the refining industry, as well as the ability to export in the world gas market; production of automobiles using nonleaded gasoline would provide potential products for the world market; improved health and food quality. |

|

|

* |

Pan American Health Organization, Guatemala |

|

** |

University of Maryland Medical School, Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A. |

DATA NEEDS

The working group concluded that no further research on lead in gasoline as a source of environmental contamination or human exposure is needed. Nevertheless, members recommended compiling a database on the extent of production and use of leaded gasolines in the Americas. The following country and regional data would be essential to a useful database:

-

permissible levels of lead in gasoline (national standards);

-

actual use of lead in leaded gasoline;

-

market allocation of leaded/unleaded gasoline (national and regional, by grade; as relevant);

-

fuels refining capacity, total and by type of unit (barrels/day);

-

other vehicle fuels in use, type and percent of market (ethanol, diesel, and the like);

-

vehicle fleet (number, age, rate of change to new vehicles, performance, catalytic converter equipped);

-

inspection and maintenance policies and practices for vehicles;

-

price of fuels;

-

trends in these factors.

REDUCING LEAD ADDITIVES IN GASOLINE

The working group agreed that there is general progress toward the phasing out of tetraethyl/tetramethyl lead additives in gasoline in the Americas. Nevertheless, a national policy of lead reduction in motor fuels as a goal for air quality improvement requires considerably more information to be both effective and to achieve public acceptance. The motor vehicle fleet in a given country represents a range of octane requirements in the fuels that power it. This diversity in octane requirement arises largely from engine design, compression ratio, mileage accumulated (a more precise indicator for octane requirement than vehicle age), prior fuel usage history, maintenance level, and operator expectations of performance. Meeting this octane requirement usually involves a combination of unit refining processes that upgrade hydrocarbon molecules to those of higher octane value and the use of additives. Where the use of additives such as lead is restricted and there has been no adjustment in octane requirement, the burden falls heavily on the fuels refinery. Making up the difference involves capital expenditures, possible export and import issues, changes in the distribution system

(additives can be blended in at many points, high-octane molecules normally only at the refinery), and a decrease in the efficiency of conversions of crude oil to motor fuel.

The introduction of additives other than lead as an option to meet octane requirements was not endorsed by the working group. Some additives, such as those based on manganese or other metals, make their own contribution to air quality problems. Other additives, such as oxygenates, including alcohols and ethers, may produce tail pipe emissions that raise significant health questions when used in cars without catalysts.

It is clear, therefore, that determining the rate of lead phasedown in motor fuels in a given country or region involves the interaction of many economic, technical, social, and demographic factors. There is also the one-time problem of purging an entire system for handling leaded fuels to be able to handle unleaded fuels. Of particular concern is the major task of cleaning the sludge from storage tanks that had been used for leaded gasoline. This sludge tends to be high in lead content; if it is not removed, can easily contaminate unleaded fuel introduced into the tanks. In an ideal configuration, capital investment by refiners and auto manufacturers, subsidies for conversion and retrofits, consumer education, clear enunciation of possibly conflicting goals, and realistic timetables should all be part of the decision process.

WORKING GROUP II

PAINT

MODERATOR: KATHRYN MAHAFFEY*

RAPPORTEUR: DAVID JACOBS**

The United States is the only country in the hemisphere where lead-based paint has been clearly identified as a major source of childhood and occupational lead poisoning. While that has important lessons, it is impossible to extrapolate the experience of the United States to Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean Basin, or Latin America, because the current use and extent of lead-based paint cannot be reliably determined at this time. Each country of the Americas, however, has unique housing, infrastructure, and regulatory characteristics that must be understood before the context or use of lead-based paint can be determined.

The working group developed recommendations on how to fill important data gaps. Only after these gaps have been eliminated can rational, cost-effective lead-based paint policies built on a firm scientific foundation be developed. The group found there was sufficient evidence in the United States and anecdotal evidence in other countries in the hemisphere to warrant two actions:

-

systematic collection of data;

-

certain preventive measures regarding current and future use.

The working group noted during the plenary discussions that the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) has already collected important data indicating that lead-based paint is an important potential source of lead poisoning throughout most of the Americas. In the United States, the U.S. Public Health Service regards lead-based paint, and the contaminated dust and soil it generates, to be the principal source of elevated blood lead levels in 1.7 million U.S. children between the ages of 1 and 5 years.

|

* |

Environmental Criteria and Assessment Office, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S.A. |

|

** |

National Center for Lead Safe Housing, Columbia, Maryland, U.S.A. |

Lead-based paint represents a difficult challenge after use because it is a source that is both highly concentrated and widely dispersed, necessitating control measures that are decentralized and relatively costly. Controlling leaded gasoline and lead in food and beverage cans, although difficult, is relatively simple compared with painted surfaces, because the source and associated control measures are generally more centralized.

The working group determined that the extent of lead-based paint exposure could be analyzed by collecting data on the amount of:

-

lead used in the production of new paint (residential and commercial);

-

old lead-based paint already existing in housing;

-

lead-based paint used on toys, furniture, and other consumer items;

-

lead-based paint used in nonresidential settings, principally bridges and other steel structures.

Two principal ways in which such data could be acquired are:

-

examination of production records, specifications, and import/export data, some of which have already been assembled by PAHO;

-

carefully designed field measurements of a small number of randomly selected representative housing units, steel structures, and consumer items to estimate the magnitude of lead-based paint as an exposure source in the country or region assessed.

The working group felt that both strategies could be pursued simultaneously at relatively low cost. Field surveys provide information on lead present in paint already applied to surfaces, and production records and import-export data could be used to assess the extent of leaded paints currently in the marketplace. The working group recognized that the quality of records is likely to be highly variable, with many records incomplete or suspect.

In designing field surveys, the working group concluded that it is essential to determine how the surveys are to be used and how small-scale pilot projects will be conducted. Preliminary assessment of the design of these pilot studies should be carried out by small focus groups. This would permit adaptation of survey designs to local conditions. Previous experience in the United States indicated that it is possible to design a survey of approximately 300 housing units to estimate the prevalence of lead-based paint hazards in an entire nation's housing stock, characterizing prevalence by region, kind of housing, age of housing, and type of building

component coated with lead-based paint. Such survey findings have helped policymakers to formulate programs that were carefully targeted to make the wisest uses of scarce inspection and control resources.

The implementation of field surveys should be done regionally or along national boundaries using already established measurement techniques. The surveys would need to be designed to account for variations, for example, in housing stock, cultural differences, geographic location, and ownership patterns. This effort should be considered a preliminary step in the development of a primary program aimed at source control. Primary prevention, however, cannot entirely replace secondary prevention (blood lead screening) or tertiary treatment of lead-poisoned persons.

Failure to determine whether or not lead-based paint is an important source of exposure could lead to significant public health problems. The working group agreed that the decision to permit the widespread use of residential lead-based paint in the United States before 1978 has resulted in literally millions of cases of childhood lead poisoning and widespread lead poisoning in construction and housing rehabilitation and construction workers, as well as very serious economic pressures on affordable housing for the poor. Working group participants agreed that other countries in the hemisphere should develop policies and programs aimed at avoiding this experience by setting goals to prevent the use of lead-based paint, both in the residential and commercial settings. Members concluded that the International Labour Organization (ILO) treaty prohibiting the use of white lead in residential lead-based paints, signed by several countries in the 1920s, while visionary, did not generally lead to enforced regulations in the few Western Hemisphere signatories.

The working group also agreed that it is important to estimate the presence of lead in other building materials, not just lead-based paint. The use of glazed tile as a floor and wall construction material, for example, suggests that new analytical methods may be needed, since current analytical methods are aimed at estimating ingestion of lead from glazes using leaching techniques. Little is presently known about the weathering or aging of lead-glazed tiles, although there is evidence that leaded dust on floors is among the strongest predictors of children's blood lead levels. Another building practice that should be examined is the use of scavenged waste materials, such as old battery casings or tires.

The working group suggests that preliminary surveys can be carried out most cost-effectively by using portable X-Ray Fluorescence ( XRF) lead-paint analyzers, which can screen many surfaces reliably, and relatively inexpensively. Laboratory-based paint chip testing techniques are likely

to be far too expensive, while chemical spot-test kits are likely to be too unreliable to provide usable data. The group recognized that widespread implementation of lead-based paint surveys (either regionally or nationally) would require significant technical assistance and training, and this would require the collaboration of such entities as PAHO or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Technical assistance of this kind has yielded benefits in Mexico, where lead-based paint prevalence was assessed in two neighborhoods. A technical manual on a variety of paint, soil, and dust sampling methods was also developed by the Pan American Health Organization (ECO/OPS, 1995). Establishment of centers to train lead-based paint hazard inspectors, similar to those funded by EPA in the United States, would provide an important forum for manufacturers, public health professionals, housing personnel, and transportation professionals to interact to develop response measures, if surveys determine that lead-based paint use was, or is, widespread. Government purchasing authority should also not be ignored as a way of limiting the use of lead-based paint.

The working group felt that a literature search of both published and unpublished studies on the distribution and extent of lead-based paints should be conducted, along with a review of occupational exposure data, to determine if building construction workers, painters, and workers in paint manufacturing facilities have had significant exposures to lead.

Finally, the group noted that substitutes for lead-based paint are readily available for both residential and commercial uses at about the same cost, and that it would be far more costly to permit the continued use of lead-based paint, with the consequent hazard controls needed in later years. While such control measures have been shown to be effective in reducing children's blood lead levels, it would be far more inexpensive to avoid use of leaded paints in the first place. The U.S. government currently has grant programs totaling several hundred million dollars to abate and control lead-based paint hazards. Experience has shown that these expenditures would have been unnecessary had use of lead-based paint been proscribed in the first place.

The working group recommended that new paint produced not contain more than trace amounts of lead-based paint (600 ppm in the dried paint film). Old, already applied paint should not exceed 5,000 ppm or 1 mg/cm2, although standards for each country may vary.

In summary, the working group concluded that data on the prevalence of lead-based paint in the Americas is inadequate to determine if it constitutes a primary source of lead exposure. Specific steps should be taken to eliminate this data gap if rational control policies are to be developed.

WORKING GROUP III

CERAMICWARE GLAZES

MODERATOR: GUSTAVO OLAÍZ FERNÁNDEZ*

RAPPORTEUR: MAURICIO HERNÁNDEZ-AVILA**

The group noted that there is little information published in scientific journals about the extent of use of lead-glazed ceramics (LGCs) in the Americas, nor is there epidemiologic data that would permit assessment of the importance of LGC as a source of human lead exposure in the Americas. For example, there are no data about the proportion of the glazed ceramic that leaches lead or about the numbers of people exposed to this source.

Published information on the impact of the use of LGC on blood lead concentrations does exist for a few, select population samples in Mexico, the United States, and Canada. Levels of exposure appear to differ by country and sample studied. For example, LGCs appear to represent a minor problem in Canada and the United States, except for a number of Hispanic populations. In Mexico and Ecuador, LGCs are an important source of lead intoxication for large segments of the population. In these two countries, LGCs are part of cultural tradition and used by a large number of families. In Mexico City, for example, it is estimated that 30 percent of families cook and store food in LGCs with some regularity.

The use of LGC is well-documented as an important source of lead for women of reproductive age in Mexico. In a study reported recently, women who used LGC for cooking and storage of foods had blood lead levels 3 µg/dl higher than a similar group that did not use LGC (Hernández-Avila et al., 1991). Also, other studies in Mexico have documented higher levels in children who live in households where food is prepared in LGCs (Romieu et al., 1995).

For most countries in the region, there is no information about regular use of LGCs, and it is likely that use varies from country to country. In the United States and Canada, the working group noted that there is more information available about the risks associated with artisans' use of LGCs, and that these data have resulted in a decline in the use of lead glazes

|

* |

Environmental Health, Ministry of Health, Mexico City, Mexico |

|

** |

Center for Public Health Research, National Institute of Public Health, Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico |

in this sector. There is also evidence of a decline in the use of LGCs in Mexico. Given that this kind of ceramic has been used for many generations in Mexico and is strongly linked to tradition, however, producers and users still generally do not identify LGCs as a threat to health. Thus, adequate control of LGCs remains lacking. Mass information campaigns have not yet been developed in most countries of the Americas; where it has been attempted, work has been impeded by governmental institutions.

Why is this? Working group members agreed that governmental and nongovernmental institutions in Mexico, for example, are opposed to mass campaigns for the public because they seek to protect those who make their living from production of LGCs. It is estimated that between 5,000 and 10,000 families would suffer economically from a decrease in public demand for LGCs. Also, cultural institutions are concerned that this tradition, which has existed in Mexico for many centuries, may disappear when consumers appropriately link LGC use to lead intoxication.

In the United States and Canada, a more organized ceramic industry predominates, and this characteristic allows for a greater degree of consumer protection in these countries. In general, large and well-established industries are more likely to comply with legislative norms. Across the Americas, however, there are also artisans and artists who cannot comply with existing norms for economic reasons, and who also are not adequately informed of the risks involved. In such circumstances the working group recommends that frits –a fused or partially fused material used as a basis for glazes or enamels –containing lead be taken off the market or that the technique for use of lead-based frits not be included in the curriculum of schools that train in the ceramic arts. The working group recommends that there also be concerted attempts through education to minimize the recreational use of lead glazes by individual or home potters.

In Latin America, producers of LGCs are predominantly microindustries, which are frequently family businesses in which the entire family is involved in the production process, and it is this householdwide participation that makes these industries economically viable. The involvement of family members in production activities and the high levels of lead contamination of the home environment seen in many instances, however, puts women and children at particular risk of chronic lead poisoning. One working group member noted that in a study carried out in communities involved in pottery production in Mexico, the highest concentrations of lead in blood were detected in women and children. Unfortunately, it was also reported that in these same communities, government interven-

tions are generally distrusted for a variety of historical reasons. As a result, working group members concluded that home technologies would not prove successful initially. In addition, there is little possibility that this sector of the industry will comply with U.S., Canadian, or Mexican norms. For example, the cost of certifying that a product is lead-free in Mexico is higher than the price of the finished product; therefore, small-scale producers would not make a profit if mandatory lead testing were required. In any case, effective government regulation is unlikely to occur in Mexico. As in many other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, artisans are geographically scattered and not easily accessible. Also, the markets in which many home products are sold are often in small, unregistered stores, which are typically mobile, and thus difficult to regulate.

The working group concluded that even large-scale industries that produce LGCs in Latin America and the Caribbean Basin would be difficult to regulate because of a lack of adequate legislation; even more important is the absence of the human and physical infrastructure required to ensure compliance with established norms. The working group, therefore, recommended that increased attention and resources be directed toward developing the minimum core of laboratories and trained personnel in each country needed to help monitor the workplace safety standards that are established.

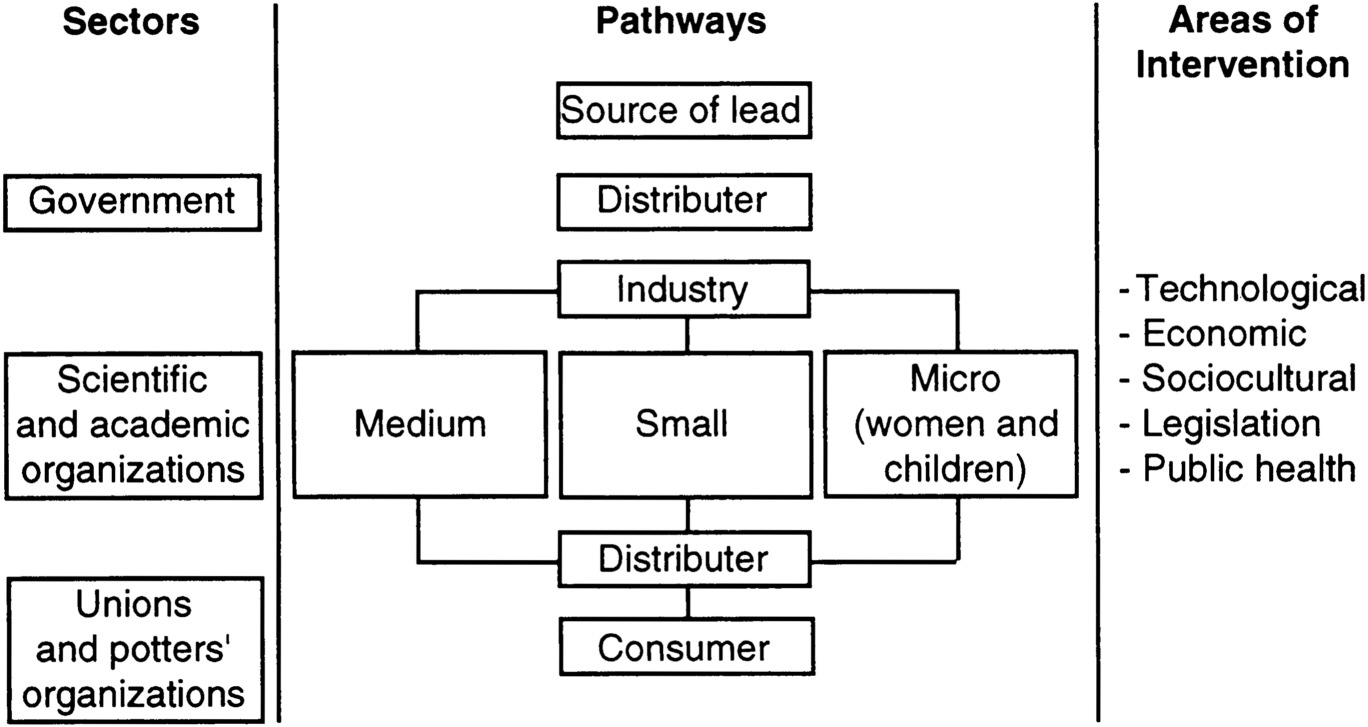

In order to successfully reduce the manufacturing and use of LGCs across the Americas, the working group agreed that all interested or affected parties should participate in decisionmaking. Figure 4-1 lists the actors involved in ceramic production and some of the potential cross-sector interventions that could be applied. Several steps are required before substitution of lead-based frits can take place. As a first step, industries that produce lead frits should be contacted by public health authorities to evaluate the possibility of substituting lead with alternatives such as boron strontium and lithium. Lead frits are not an important source of revenue for these companies; therefore, economic incentives in the form of short-term industrial subsidies should be introduced into negotiations to stimulate a rapid transition to lead-free frits.

A problem that may arise with the substitution of lead is that the current alternatives—boron strontium or lithium—may not work well under the fabricating conditions of most microenterprises or cottage industries. In these companies, ovens are often primitive and do not reach the temperatures required for the new materials to “take” (the low temperature compliance of lead is the main reason for its popularity as a glaze additive). Research is needed to better understand the possibilities of substitution

Figure 4-1. Actors involved in the fabrication, commercialization, and use of ceramics.

and to evaluate, under real conditions, the performance of potential alternatives. At the same time, the working group agreed that it is important for health educators to work with unions and artisans to increase their knowledge of lead and the health risks it poses to the worker, his family, and the consumers of his product.

An additional point noted by the working group is that the substitution of alternative substances for lead creates a need to restructure the traditional modes of production, recognizing that past experiences in other domains has demonstrated that cultural traditions are very refractory to change.

Several issues were raised in relation to the safety of the new alternatives. The working group agreed that research should be conducted to evaluate the safety of potential alternatives to lead by investigating the amount of the substance that can be expected to leach to food and its potential for negative health effects.

The working group concluded that there is a need for interventions that guarantee the permanence of cultural values attached to LGCs and recognize the intrinsic value of the artisans' activity, yet promote a safe, lead-free product for consumers. These interventions should be carried out with the participation of all sectors involved, including public health institutions, artisans, government, and unions. Interventions identified for the short term include substitution of lead in the frits and, in the long run, the transfer of technology for the development of kilns that function at higher temperatures with the use of more efficient fuels.

WORKING GROUP IV

INDUSTRIAL AND OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH

MODERATOR: ROBERT MCCONNELL*

RAPPORTEUR: JULIETA RODRÍGUEZ DE VILLAMIL**

Working group participants agreed that in order to properly address the issues of lead in industrial and occupational health, it would be necessary to complete a preliminary inventory of industries and economic activities associated with occupational exposure to lead with a focus on Latin America and the Caribbean.

The preliminary inventory prepared by the working group included manufacturers and recyclers of batteries; manufacturers of bronze articles; manufacturers of leaded cables; chemical operations; building demolishers; gasoline attendants; primary and secondary smelters; manufacturers of leaded ceramicware glazes and ceramics; manufacturers of bullets and lead-containing weapons; concerns that melt and cast leaded products; the jewelry trade; mining operations; manufacturers of steel; plumbers; industrial and house painters; stained-glass makers; manufacturers of leaded pigments; chimney cleaners; soldiers; shipbuilders; manufacturers of lead tetraethyl; manufacturers and repairers of radiators; automobile repair concerns; general construction operations; waste disposal concerns; artisans working with lead (religious figurines, lead soldiers); the plastics and metal industries; and manufacturers of refrigeration, lightbulbs (spotlights), and cosmetics.

For each of these industries or occupational activities, it is necessary to consider the size of the company (large, medium, small, or micro-industry) in order to establish the following determinants of lead exposure:

-

intensity of exposure;

-

number of workers exposed;

-

trends in exposure;

-

potential preventive and control activities, such as industrial hygiene.

|

* |

Pan American Center for Human Ecology and Health, Pan American Health Organization, Metepec, Mexico |

|

** |

Occupational Health, Ministry of Health, Colombia |

Using estimates of lead exposure by occupational category and drawing from Dr. Isabelle Romieu's plenary presentation, “Prevalence of Exposure and Quality of Information, ” the working group ranked the potential for lead poisoning among different categories of workers and identified needs for additional etiologic studies and intervention strategies for prevention and control in each case.

As a first step, the working group agreed on the need to extend the preliminary survey conducted by Dr. Romieu and colleagues. Acknowledging the difficulties in collecting information on the extent and severity of lead poisoning in many countries of the Americas caused by a lack of existing data or data collection systems, the working group recommended that a national intersectoral group be organized in each country for the purpose of collecting requisite data in a consistent and ongoing manner. Data collection should be supported through country visits by international researchers with expertise in surveillance and monitoring of lead exposures in the population.

The working group identified a number of potential strategies for reducing population lead exposures, with the following emerging as themes:

-

the substitution of lead in industrial processes and the reconversion of corresponding industries;

-

standardization or technical normalization of biological and environmental monitoring in the workplace; education and training in support of “the right to know, to participate, to transparency”;

-

the necessity of technical support to implement prevention and control activities in industrial hygiene, infrastructure of occupational health, communication of risk, and human resources;

-

provision of incentives, training, and financing for standardized research on prevention and control of lead poisoning across the Americas;

-

improvement of conditions of work in microindustries and reduced paraoccupational exposure to lead;

-

expansion of training of experts in occupational health in order to strengthen human resources, especially in the Caribbean Basin and Latin America.

The working group concluded that reducing occupational exposure to lead will require the involvement and commitment of a broad range of players, including government, employers, workers, unions, and nongovernmental organizations (NGO's).

Government should design and implement national and international occupational health policies in order to control or eliminate lead exposures. In some countries of the hemisphere, legislation in support of the fulfillment of norms and regulations will require modernization of the workplace in accordance with the developmental stage of that country. National governments should provide the financial support necessary to encourage industrial control or elimination of lead exposures. Lead exposure reduction in the industrial sector should be a priority in discussions with international donors. The working group recommended that government also provide adequate health care for workers exposed to lead; it was recognized that an organized strategy is required to support step-by-step modification of the structure of occupational health services and other relevant, longer-term occupational health objectives.

The working group agreed strongly that employers must assume the responsibility of risk resulting from worker exposure to lead. Members recommended that employers organize occupational health services that include, for example, blood screening, protective equipment, and areas to wash hands to control exposure to lead in the work environment. It was also felt that it is the role of the employer to ensure better health and work conditions for workers, even in instances where lead cannot be substituted in the workplace. In addition, it is the responsibility of individual employers to follow regulations and standards controlling exposure and the use of lead.

Working group members acknowledged that workers also have a role in ensuring the safety of their workplace. For example, workers should be willing to collaborate with employers in the implementation of rules for controlling exposure, including accepting and adopting safe places to work with lead. It is the responsibility of the individual to comply with the recommended preventive measures, to avoid unsafe habits and lifestyles—for example, cigarette smoking—and prevent paraoccupational exposure of lead within the family. Unions should educate their workers to ensure that these responsibilities are fulfilled.

NGOs can assist in this process by communicating the risks of working with lead through training of exposed workers, their employers, and the community in general. All actors and sectors involved should guarantee the sufficient availability and allotment of human and financial resources to allow for alternative solutions to lead where they exist. A Job Exposure Matrix that ranks occupational settings on the basis of the extent of lead exposure should be developed to guide occupational prevention, control,

and monitoring activities. Special attention should be given to the evaluation of these programs with respect to their success in preventing or controlling occupational lead exposures.

The working group recommends development of standardized occupational and environmental policies on lead poisoning prevention that are standardized across the Americas. Policies should be directed toward primary prevention, identification, and timely treatment of lead poisoning when it occurs, and toward appropriate compensation for cases of incapacitation from lead poisoning. Industries should also guarantee relocation or retraining of lead-poisoned workers as needed.

The following are general conclusions and recommendations of the working group:

-

Government, in alliance with workers and employers, should develop the capability to monitor the health of workers (and their families) in small and microindustries where lead is utilized;

-

International standards for surveillance and monitoring, worker safety training, and laboratory quality control should be developed and applied in all countries of the hemisphere;

-

National and international campaigns should be developed in order to increase awareness of the adverse effects of lead on health and of the benefits of prevention and control. One example might be the creation of a “World Lead Day;”

-

Interventions for handling workers exposed to lead should include options for retirement, job relocation after the withdrawal of the exposure, and adequate compensation in case of disability;

-

Workers as well as employers have a responsibility to implement and maintain a safe workplace.

WORKING GROUP V

FOOD, WATER, AND WASTE DISPOSAL

MODERATOR: LEN RITTER*

RAPPORTEUR: TANIA TAVARES**

This working group profited from the contribution of representatives from industry, government, academia, nongovernmental organizations, and trade unions from five different countries of the Americas.

The pathways of lead contamination of water and food are multiple and interrelated. Strategies to reduce lead exposure through these pathways will, therefore, require interrelated solutions.

WATER

The main sources of lead contamination in water identified by the working group were: lead in water pipes and plumbing fixtures; residue from lead shot in rivers, lakes, wells, and other outdoor sources of drinking water; industrial and lead pesticide runoff; leaching from industrial and urban landfills where lead-containing wastes (such as batteries and paint) are dumped; deposition from atmospheric emissions deriving from leaded fuel and industrial activities; and social practices such as the collection of rainwater for drinking in high-density traffic or industrial areas. Remediation through addition of phosphate to water sources, a common intervention, was considered useless as it merely changes soluble lead into particle form, which can be ingested as well. The new practice in Japan of lining old lead pipes with plastic tubing was brought to the attention of the group, but there are yet insufficient data on the cost-effectiveness of this method to warrant a recommendation for adoption.

FOOD

The main sources of lead in food are leaded solder in food cans; lead glazes used on foodware; leaded fuel and industrial emissions that can reach food

|

* |

Canadian Network of Toxicology Centres, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada |

|

** |

Federal University of Brazil, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil |

from atmospheric dry and wet deposition, contaminated irrigation water, or lead-contaminated soil; and leaded pesticides. The extent of information on the distribution and use of leaded pesticides in the Americas was viewed as extremely limited. The working group, therefore, did not focus discussion on this source. It did, however, recommend that attempts be made to determine the importance of leaded pesticides as a source of lead poisoning in the hemisphere.

STRATEGIES

The working group focused on identification of strategies to reduce lead exposure from food, water, and waste sources. Four strategies that have proven successful in one or more countries of the region were identified in the hope that they may be adopted by other countries of the hemisphere.

-

The first strategy involves elimination of lead solder in canned foods through replacement of lead-soldered joints with electrically welded joints. Canning industries in Mexico and the United States that have refitted accordingly have realized the following benefits: a 3–5 percent reduction in raw materials, resulting from the smaller welded joint; no net additional costs from retooling, because materials costs most often offset equipment costs; a smaller welded joint provides a larger surface area for advertising; a decreased risk of liability; and potential for increased market share. The working group concluded that to be successfully undertaken in most countries of the Americas, this initiative requires support from both industry and government in the form, for example, of government subsidies available to the manufacturer, legislative regulation, and enforcement.

-

The second strategy is directed toward the elimination of lead in fuels. This, in turn, will reduce lead contamination of air, food, and water. The working group did not address this issue in depth, given that it was the focus of another working group.

-

The third strategy is targeted toward reduction of point source lead emissions, including cottage industries. The working group felt that initial progress toward this end could be achieved first through an inventory of such potential sources. Strategies for reducing lead exposures from specific categories of sources could then be addressed as a first option by collaborative alliances among industry, government, community-based action groups, and labor unions. Involvement of

-

industry in source inventory and identification of potential solutions will help encourage industry to follow through on reduction, abatement, and remediation measures. The incentives for industry to participate in this process are improved public image, decreased liability costs, increased market share, and long-range economic gains. The working group recommends that support for involvement of the necessary multiple players should come from industry, government (through subsidies, legislation and enforcement, technical support, and information), the Pan American Health Organization, the World Bank, foundations, and other NGOs.

-

The fourth strategy to reduce exposure to lead in food and water is by improving household family practices (domestic hygiene). The working group concluded that the responsibility for reducing lead exposures in the home environment lies with the community itself, specifically the individual households. The extent and effectiveness of domestic hygiene practices could be increased through community and individual education, local empowerment (that is, “train the trainer”), and widespread implementation of such practices as handwashing, peeling food, sweeping and cleaning of the house at regular intervals, and not collecting rainwater for drinking in lead-lined containers. Local health units and levels of government, community organizations, NGOs, and charitable foundations should be encouraged to develop and provide these public education programs to increase awareness of the hazards of lead and knowledge of effective preventive measures.

WORKING GROUP VI

TECHNIQUES FOR IMPROVED SURVEILLANCE AND MONITORING OF LEAD EXPOSURE

MODERATOR: HENRY FALK*

RAPPORTEUR: HOWARD FRUMKIN**

The working group participants agreed on the conventional definition of public health surveillance as applied to lead: the systematic, ongoing collection, analysis, and dissemination of information on lead exposure or lead toxicity, with the ultimate goal of preventing toxicity.

The following were identified as important factors in surveillance programs:

-

Surveillance is important, not for its own sake, but to provide information to support prevention. The goals of surveillance programs may vary depending upon local needs and priorities. In any case, goals should be set at the beginning of the program and may include case-finding, monitoring population trends, evaluating the efficacy of interventions, generating data to persuade policymakers, and education.

-

Both biological sampling and environmental sampling may be important components of lead surveillance programs. Traditional public health approaches have relied heavily on biological sampling; because lead enters the body through various routes that may be difficult to measure, and lead absorption, even at low levels, requires prompt medical and public health response, biological sampling continues to be a mainstay of lead surveillance. This is the case-finding function. In addition, biological sampling helps to evaluate the success of prevention efforts and to monitor overall population trends. Environmental sampling may be equally or even more appropriate in some circumstances, however, and is often overlooked, particularly for monitoring sources of lead exposure. When resources are scarce, careful consideration should be given to the relative importance of each approach.

|

* |

Division of Environmental Hazards and Health Effects, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.A. |

|

** |

Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.A. |

-

It is essential to target surveillance to the greatest extent possible given search resources in most countries of the Americas. For biological sampling, high-risk populations should receive priority. For environmental sampling, environments with a high probability of substantial lead exposure should receive priority. The working group discussed results from the recent NHANES III (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) in the United States, and although members praised the precision and generalizability of the results, they agreed that a general population survey like NHANES would not currently be a high priority in most countries of the Americas because of cost and feasibility. In contrast, the members agreed that occupationally exposed populations, communities with exposure to point sources, communities with other high-level exposures (such as to lead-containing ceramics), and susceptible subpopulations such as children and pregnant women should be a high priority for lead surveillance. The choice of a population or potential exposure to be targeted may be made based on various kinds of information, such as screening questions, published literature on patterns of lead use, and information from previous surveillance.

-

There is a critical need to provide more laboratories and train technical personnel throughout the countries of the Americas. During the workshop, Dr. Robert Jones of the Centers for Disease Control described the CDC lead testing proficiency program, which is free to participating laboratories. Dr. Henry Falk, also of the CDC, discussed possible CDC support for training laboratory personnel in at least one lead testing facility in each country or subregion of the Americas. Perhaps this could be combined with outside support, if available, for the acquisition of lead testing equipment in these labs. This effort might be coordinated by the Pan American Health Organization.

-

Successful surveillance programs should be simple and inexpensive, and to the extent possible should take advantage of existing programs and facilities. For example, lead testing might be added to programs that test children for other health conditions, or laboratory-based reporting might be required.

-

Lead surveillance programs need certain guidelines and procedures to function efficiently and equitably. Examples discussed in the workshop included reference levels for lead in food, water, and other media; in the occupational setting, workers who are tested must be guaranteed that their medical confidentiality will be protected, and that the finding of an elevated blood lead level will result in removal from exposure,

-

treatment if necessary, and maintenance of wages, but in no case dismissal or retribution; and in both the environmental and the occupational setting, any surveillance program must include provisions for follow-up of elevated blood lead levels, including removal from exposure, treatment if necessary, and abatement of an ongoing hazard.

-

Surveillance programs provide an invaluable opportunity for education of people exposed to lead. It is essential to link education with surveillance.

Surveillance programs, while often planned and implemented by specialized public health personnel, should involve other health care providers in planning, implementation, interpretation of results, and follow-up actions. Groups of special importance in this regard are practicing pediatricians; occupational health physicians; and state, local, and provincial public health authorities.