5

Research Restructuring and Assessment at Xerox

John Seely Brown

I must confess that this is the first time I have been on a panel where I am the fourth speaker and feel as though I represent a start-up company. It is usually the other way around. But after IBM, AT& T, and Ford, I represent the little new guy—Xerox. We did not get into this issue of restructuring corporate research because of budget issues. Seven years ago, there was a book published called Fumbling the Future: How Xerox Invented, Then Ignored, the First Personal Computer (Smith and Alexander, New York, 1988). It made us realize that we needed to “get our act together” and to do our own restructuring and our own measurements before somebody asked. So, we have been looking at these issues for some time, and I am going to have a slightly different view than the prior speakers.

ORGANIZATION OF RESEARCH AT XEROX

I would like to begin with our organizational context. It helps to illustrate some of the interesting issues in the management of research and technology and some of the measurement problems. We have eight business divisions and a group called Corporate Research and Technology (CR&T), headed by Mark Myers. The CR&T group comprises a very small strategy and innovation group, three technology platform centers, and three fundamental research centers. I call this out initially because the performance measurements of the technology platform centers are going to be somewhat different from the performance measurements of the fundamental research centers.

The second thing worth noting is that we have only a partially centralized R&D group. The entire Corporate Research and Technology operation represents about 25 percent of the R&D dollars inside Xerox, which means that 75 percent of all of development is done in the business divisions. Why did we not push everything into the business divisions, or why did we move from a place that was almost all centralized to spreading a lot more of it out in the business divisions?

One of the interesting things that makes this decentralization work is our Technology Decision-Making Board, which meets once a month. The eight business division presidents, the heads of the technology platform centers, and the heads of research all sit on this board. The chairman is Mark Myers, who is a member of the head corporate office. We are not allowed to send substitutes, which means the business division presidents must learn to traffic in technology issues and, equally important, the heads of research have to learn how to have interesting, useful conversations with the business division presidents. Mark has perfected the processes of running this Technology Decision-Making Board over the last couple of years. This board is now a very successful mediating device where we really do put our cards on the table. That is a big change. In the past, we hid a lot, but we are beginning to realize the value of exposing ourselves more. If there happen to be conflicts that cannot be resolved by the board, Mark Myers can bring the issue to the corporate office.

TABLE 5.1 Some Significant Shifts in Research

|

Old Research Paradigm |

New Paradigm |

|

|

Invention |

→ |

Invention plus innovation |

|

Isolation from business |

→ |

Deep awareness of business strategies |

|

Opaque organizational structure |

→ |

Clear line of sight Technology markets Internal workings of Corporate Research and Technology |

|

Creating new technologies |

→ |

Creating new technologies Creating new businesses Creating new business models Identifying and nurturing new core competencies Creating destabilizing events |

|

Obscuring responsibility |

→ |

Embracing responsibilty |

|

Ivory tower |

→ |

Ivory basement |

Part of the purpose of still having some centralized R&D is to create synergy among the business divisions. If you break a company up into business divisions, in what way is the whole a sum of the parts? One of the ways is by having a small centralized research group create common technology platforms that can be used by multiple business divisions. So, one of our measures is the number of technology platforms we create and how many of these get shared across business divisions. If you can show real shareability, then you have a synergy factor that justifies some centralization. Also, by creating platforms that are shared by several business divisions, you get an implicit corporate architecture across the various product platforms, and this may be the best way of getting an architecture accepted in a corporation. So, there are some subtle cultural or social issues that come out of this measure.

What I want to do is to discuss a set of shifts that we have been going through over the last three to five years. These are summarized in Table 5.1.

I want to talk a little bit about the theory underlying some of these shifts, but before I do that, I need to mention that what we are really talking about is a cultural shift. It is not just a cultural shift of research; it is also a cultural shift of the corporate world at large. So the question is, How do you bring about cultural changes in the research community? That is done partly by measures, but it also is done by basically changing the language, by reframing some of the distinctions of research and technology transfer.

What I am going to talk about is how we have been changing our discourse and some of the techniques for that which turn out to be as important as the measures themselves. In fact, although measures are important, we feel that if our success is going to turn on measures alone, we will have already lost the game! Measures, without having established the credibility of the research organization, are not going to change the perception of our credibility.

A major issue is how to establish that credibility. Then, against that backdrop, measures have quite a different tone and purpose— indeed, they then become a tool we can use for ourselves for self-improvement as much as a “monitoring” tool used by others. So, how do some of these shifts change the way we see ourselves?

The first is the recognition that our jobs as researchers are not just to produce the invention, but also to share some of the responsiblity for making it into an innovation. By “innovation,” we mean implementation of the invention. Perhaps one of the reasons top-level management often comes out of research is because we quickly learn that, often, as much creativity goes into the innovation part of the invention as into the invention itself. Why is that important? Because it transforms the arrogance of researchers. Researchers need to learn that they are not the only creative people and that, in fact, the amount of creativity it takes to unfreeze the corporate mind and to get a radical new idea accepted requires some innovative “out-of-the-box” thinking, just as the original invention did. Although this is an obvious business goal, it actually starts to change the way we, as researchers, view ourselves.

The second shift—and this has been talked about a great deal this morning—is the sense of moving research from being totally isolated from business to being much more deeply aware of business issues. Although we are not trying to turn researchers into general managers per se, we do want them to be participants in a broader set of conversations and to be able to hold their own in those conversations.

A third shift for us was to view corporate research and technology, especially corporate research in this case, not just as creating new technologies, but also as taking on the task of creating, in addition to technologies, new businesses and new business models. This may seem bizarre, but new business models have to be invented, which is another aspect of innovation. This is very important in a rapidly changing world. Not only do we as researchers have to be prepared to have multiple careers, but the corporation itself also has to be prepared to have multiple new core competencies emerge. Who is going to determine what those core competencies are? Who is going to nurture them, and who is going to make them catch on? It is going to be research. So, corporate research needs to be responsible for the renewal of the technology capability of the corporation, as opposed to just the technologies themselves (as are our universities). To actually develop those core competencies, it is necessary to infiltrate the structure of the organization, not just remain in research.

Another shift has to do with creating our own destabilizing events; that is, how do we completely transform our industry or our market? The reason I bring this up is because Jim McGroddy was talking about one of his measures having to do with the IBM business divisions ' satisfaction with research. It is very important to realize, however, that if you are in the process of creating destruction, a particular business division may not be very happy with you, especially if you are doing a great job.

Thus, customers may be fairly tricky, because if it is not going to be research that is leading to creative destruction, who is it? You cannot just ask business divisions how happy they are with you. Obviously, there is a way around that problem because, for example, you also can measure how many new business divisions you have created, how rapidly they are growing, et cetera.

The fifth shift, which is one of the hardest cultural transformations, is how we move from obscuring responsibility to embracing responsibility. It is all too easy for us in the research center to talk about “ those idiots” out there that could not adopt a new idea, and we could easily become very cynical about just how closed minded everybody else is. It is an interesting move when you say, the responsibility stops here. If we cannot get these ideas accepted, whose fault is that? It is a collective fault. How do you turn this into a useful, reflective experience?

The final shift is how we think of ourselves as moving from, if you like, an ivory tower to an ivory basement. What do I mean by that? I think one of the things we have learned is that the classical distinctions of basic versus applied research really harm our ability to have useful dialogues with each other as researchers and with the business divisions.

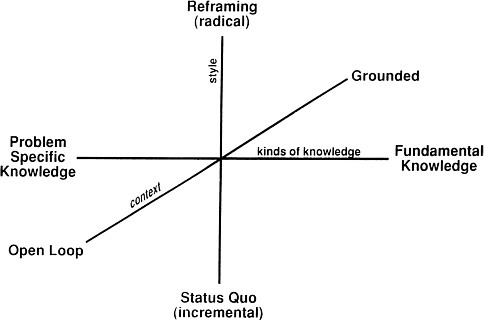

Figure 5.1 presents a framework that we have been pursuing for some time, which we call pioneering research—pioneering research meaning doing both radical and grounded research. We go back to the etymology of the word “radical,” meaning going to the root of the problem, as well as the popular meaning of “radical.” Radical research to us means that you go to the root of the problem and then, you are willing to reframe the problem when necessary.

“Grounded” means that you are deeply immersed in the class of real-world problems you are trying to crack. That is not “mission-oriented” research. It is completely different from mission-oriented research. Grounded research is going to the root of a class of problems when you know intuitively why those problems are important and you can be fluent in explaining why they are important. We have identified three dimensions of research having to do with the context, style, and kinds of knowledge that come from it. We no longer think of a particular research project as being basic or applied, but rather as being a trajectory in this three-dimensional space. The dimension that I am going to focus on is the one called context—the context of open-loop research versus grounded research.

At the founding of NSF almost 50 years ago, there was a sense that the scientific community unquestionably produced a great deal for our money, perhaps because so many of the researchers we were funding had come through the Depression and World War II and had for years confronted a class of real-world problems, but had not had the opportunity to step back and go to the root of those problems. When NSF was founded, I believe most researchers were deeply grounded, but that, through time, we have become increasingly disconnected from that grounding context, so that we have almost moved into an open-loop situation, where basically we are working on problems that our colleagues tell us are important. That may be too strong a statement, but it is at least interesting to think about.

FIGURE 5.1 Framework for pioneering research.

One last comment on this is that if you think about this notion of pioneering research, there is a slight paradox. I am suggesting that you start out very connected to a set of real-world research problems, then you pull back and become disconnected as you go to the root of those problems, and then you reconnect when you have solved the fundamental problem that you are going after. The reason I think this is important is that a corporate research organization must have the freedom to disconnect as well as connect, and this is only likely when research is separated from the daily crises of creating products in a business division.

Let me mention another change having to do with technology transfer. As a caricature we have all understood that research used to invent something, “throw it over the transom,” and then expect these poor developers to do something with it. This, of course, is a nice recipe for everything except success! What we have been looking at—and partly this is a function of our Technology Decision-Making Board—is the formal processes as well as a set of informal processes for managing technology transfer. It is the coupling of the formal with the informal that I think is the secret. If you leave everything up to an informal process, then you must rely on measurements or charisma to prove your worth. If you are trying to do everything formally, however, you get cookie-cutter recipes that do not do justice to the individuality of each situation. Ideally, you would like to keep the formal processes elegantly minimal and have them structure the conversations of the informal processes.

A major part of our formal process concerns contracting. Let me briefly describe this. It is one form of measurement, but it was done for several reasons. Probably the biggest one was that our chief executive officer asked us how much he should spend on research. Is there any way you can tell from an a priori argument how much we should be spending on research?

We had to answer, of course, that we did not really know. In fact, I now have a small research project trying to answer that. We are trying to look at research as one of the critical elements in enhancing the adaptability of the organization in a rapidly changing world.

As an underlying metaphor, you might think about research as providing the genetic variance in a species. If you do that, you can use some mathematics from population ecology to show how increasing the genetic variance

helps you adapt in a more rapidly changing landscape. This is a new form of argument that we are working on, but it is at best a form of argument.

A more empirical approach is the following. We have put in place a contracting mechanism, in which the company allocates a certain amount of money for the business divisions to contract with the CR &T over a multiyear period. This is an attempt to put in place over time some kind of process to see what the alignments really are, what the collective judgments are, and so on. The business divisions are allowed to go outside the company to buy their own technology. If they keep doing that rather than use our research output, that will tell the head corporate office something.

Finally, let me say that in all this discussion about change there is a certain irony. We as researchers want to be at the cutting edge, but we are still deeply conservative. Several times in Jim McGroddy 's presentation, he talked about the joy of researchers engaging in deep market connection, but then he kept talking about their insecurity. If you think about it, we are not worth much as researchers if our intuitions are not honed, and honing intuitions takes time. So, there is, I think, a good reason to expect that the research community should be fairly conservative.

ASSESSING RESEARCH AT XEROX

Measures of research productivity are very important to us, even without asking how it connects to creating business value. Table 5.2 shows the results of a recent survey, a rating of U.S. research institutions in the physical sciences over a 10-year period by the impact of their publications, determined by the total number of citations divided by the number of papers. This is a well-accepted metric, and it turns out that under this metric, two groups that you might not think of as having the world's best physics operations come out on top, namely AT&T and Xerox.

The difference between Xerox and AT&T is indistinguishable really, but it is strange that both would lead all the universities. How can that be? If you think about it a moment, you realize that researchers in industry do not have to publish to be promoted. We tend to write papers only when we have something that we really believe is worth publishing, and so it is not surprising that those get cited more. Even well-established metrics can have interesting side effects. Nevertheless, we are increasingly convinced that the classical measures of research having to do with papers, citations, and citation impacts have some value, but they are far from the whole story. Patents are at least as important a measure because they become a critical part of how we create cross-licenses.

The traceable research contributions and new products are another measure, but it is always going to be arguable. There are infinite ways to double count, and so such a method will always lack credibility. If we do not have independent credibility, these measures will be unconvincing at best.

TABLE 5.2 Top Ten U.S. Research Institutions in the Physical Sciences, 1981-1991, Ranked by Citation Impact

|

Rank |

Name |

Papers |

Citations |

Impacta |

|

1 |

Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton |

1,462 |

25,538 |

17.47 |

|

2 |

Xerox Corporation |

1,619 |

26,516 |

16.38 |

|

3 |

AT&T Corporation |

10,340 |

169,031 |

16.35 |

|

4 |

Harvard University |

7,049 |

110,760 |

15.71 |

|

5 |

Princeton University |

5,593 |

85,423 |

15.27 |

|

6 |

University of California, Santa Cruz |

1,541 |

22,963 |

14.90 |

|

7 |

IBM Corporation |

8,929 |

127,092 |

14.23 |

|

8 |

University of California, Santa Barbara |

4,583 |

64,744 |

14.13 |

|

9 |

Caltech (including Jet Propulsion Laboratory) |

9,160 |

128,919 |

14.07 |

|

10 |

University of Chicago |

4,781 |

65,203 |

13.64 |

|

a Total number of citations divided by number of published papers. SOURCE: Institute for Scientific Information, Science IndicatorsDatabase, 1981-1991, Philadelphia. |

||||

Thus, measures and credibility must go hand in hand in this particularly murky world. Perhaps equally important is that we as researchers are going to have to stop kidding ourselves about the significance of our own work. I remember I got all the researchers at the Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) together, and one young researcher from the computer science lab asked in frustration, “John, what does it take to convince you that my work is really important?”

I said that was the wrong question. What does it take to convince yourself that your research will really pay off? I said we are all skilled at writing those last paragraphs in grants that explain why our project is so critical, but those paragraphs tend to be disingenuous. How do you move from that to a place where you really believe that you have made the right judgment call yourself, especially if you are willing to go beyond just looking at your community for concurrence?

Again, I stress that establishing credibility is at least as important as the measures themselves. As researchers, we must start to take a more active role in shaping the discourse about how research pays off.

Perhaps one of the most critical questions is how we, as representatives of different research communities, get our own act together so that we can speak with a clear, single voice. If we do not do that, we are going to be torn to shreds by the competitive desires of the business divisions. What we have done at Xerox is create a laboratory manager's laboratory. It is a laboratory for laboratory managers to reflect on their own practices. There is no leader. I happen to be just a member of that group, although I am their official boss. What we are trying to do is to leverage the diversity of the different laboratory managers in order to facilitate our ability to triangulate on better measures, on errors we have made, and on things we did not understand correctly. We hold weekly two-hour sessions and quarterly off-site meetings.

Related to this, John McTague made the comment that communication is one of the biggest problems in a large corporation. It is also true in little start-ups like Xerox. Is it not curious that both of us talk about communications as a major barrier in making our corporations more effective, yet neither of us funds basic research into how to create shared understanding across the organization?

I will conclude with five suggestions for the National Science Foundation:

-

Encourage the scientific communities to become as conversant in issues of commerce as they are in national defense.

-

Get the various scientific communities to set their own priorities with an eye to the above.

-

Consider a new kind of partnership between universities and industry for creating overlapping communities of practice: (a) industry with universities (refreshing skills), and (b) universities with industry (grounding of research).

-

Turn the issue of measurements into an ongoing research topic for the various research communities, to improve our understanding of them.

-

Change the funding discourse from one of rights to one of privileges.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

DR. BABA: Thank you, John, for a wonderful presentation that I really enjoyed. I especially liked your comments about researchers being connected, then disconnecting for a time, and being reconnected again. I want to pursue that with a question for you. I am a program manager at the National Science Foundation. Many of my colleagues view the research community as their customers; they are really trying to serve the research community. That is where the ideas come from and the real fundamental knowledge is developed. So you cannot really think about the NSF without thinking about those research communities in the universities, their position in society, and how connected they are. Are they isolated from the rest of society, or are they connected, so that they have that problem-specific knowledge and they have a deep understanding? Have you at Xerox thought about how to position researchers in universities in a state of connection with industry and then also have them connected with Xerox?

DR. BROWN: First of all, you might even reframe your initial question in terms of NSF being the coupling element impedance matcher to the real customer, which is the taxpayer. So you help researchers get connected to the customer and then you provide multiple kinds of resources, as I provide resources for my researchers—not just

money, but also an ability to help them take their ideas and have a greater impact on the world. Our researchers do not think of us doing that, but we help amplify the impact of their ideas. NSF could think of itself in that way, too.

You obviously have gotten my point about the language we have used. We have flipped the issue around with amazing success. Instead of asking our fundamental researchers what have they done for the company, we ask them how they have leveraged the company to advance their own ideas. As soon as researchers start thinking about that, they realize that these other corporate people are allies and they ought to start learning their language. What are their problems, and what fundamental research ideas can help them?

In going back to mathematics, one of our most theoretically gifted researchers is now in Rochester working with our engineers in finding new ways to build scheduling software for a critical part of our copier machines. On his own, he found this connection and the problems are causing him to extend his constraint algebras into dealing with temporal logic in new ways, and he is turning out incredibly good theoretical work. He is getting fundamentally new ideas, plus the corporation is winning. That is the sense of excitement that is possible if you can flip this whole question around. Universities do not do very good software engineering, nor do corporations. But university researchers do not even know what a software engineering task is, by and large, because they have not trafficked in real problems of building and maintaining large commercial systems. Yet the people who are doing software engineering do not know what a theoretically elegant idea is in software design. We ought to be able to bring these two communities of practice together and have a win-win situation.

DR. LINEBERGER: An issue related to all of that is, in many ways, what you have described as a mapping process, where you have talents, problems, and the ways in which cross-fertilization takes place. A related question that faces the National Science Foundation, and obviously faces you in the restructuring of your laboratories, is, What should be in this pool that you are mapping? If, for example, one has to give more or less emphasis to various areas, how do you decide that specialization in Nubian mummies is something that is terribly important to the future of the corporation or the National Science Foundation? That is an important question because, in effect, if at some level the skills that one cares about are not in this pool that you are thinking of mapping, the idea never comes to you.

DR. FROSCH: To address this problem, you can make a list of the business problems you want to solve and what kind of knowledge is necessary to solve them. Two things happen. One is that you discover a much richer set of answers than people normally have. The second is you discover that the problems are hierarchically organized—that is, mathematics does not appear as the competitor of combustion chemistry. For instance, you need combustion chemistry to design an engine. In order to work in combustion chemistry, you need mathematics, and so forth. You can show this as a matrix, or a whole logic tree of things you would like, but you may never find out about Nubian mummies that way. In fact, there is probably no way to find out about Nubian mummies, except by increasing the collision cross section of apparently unrelated ideas. You need an inelastic collision cross section of researchers for business problems. That is what is being discussed here.

DR. LINEBERGER: One has to find a boundary. It is easy once one ascertains that, but in fact, it is not an easy question.

DR. BROWN: Let me give you an idea of how we probed the boundaries. One of the things that we have found incredibly profitable is having a very aggressive summer intern program. The primary purpose of bringing the interns in is to challenge us. I meet with them on the day they arrive, and I also meet with each one during the summer. I tell them that their job is to hassle us and to point out what we are not seeing out there. This is different from the classical notion of bringing in scientific advisory boards, who already “know” what is (or was) important. It has helped remove some of the dogma at PARC. We used to have our own private programming language. After about the fifth year of being attacked by these graduate students, the researchers themselves said that maybe we were doing something wrong. We finally threw it out.

DR. McTAGUE: That is another point. At Ford, we do not say, “I am an engineer making an engine, and I want to make sure that the laboratory has somebody working on Nubian mummies.” What we do is make sure that the person who is working on Nubian mummies can convince himself or herself that there is a reason for being at Ford. We ask for self-certification.

DR. FROSCH: There are all sorts of devices. You can purposely hire a small fraction of people from unlikely specializations, and just throw them into the pool and see what happens. What always happens is they find some problem that somebody was working on and could not solve, or they invent problems. Frequently, they are very important problems.

DR. BROWN: I think another key part of it is how much of our time is spent challenging background assumptions. How much is set aside at NSF for people who want to challenge fundamental background assumptions? Do you set aside money to probe the fringes, especially cross-disciplinary ones? The peer review system is not going to do it. Researchers are conservative.

DR. GOLDSTON: That is something that is more at the intersection of NSF problems than of industry ones. Everyone says one of the trends in industry is going more outside the industry labs for research. When industry goes to universities for research, it is acting somewhat like NSF, albeit for a different purpose. What kinds of things are you funding in the universities? How do you evaluate whether they are what you need? Do you do something different when you are going outside your labs than when you are staying inside?

DR. BROWN: We do not provide that much funding to universities. We have several institutes—for example, at Cornell—where we work jointly with the computer science department. One of the most surprising high-payoff benefits has come from taking a professor at a university and funding that person full-time as a Xerox employee while he or she is still a full-time professor. The catch is that they only get to keep four months of their salary for themselves, with the other eight months of funding going to anything they want in the way of supporting students that they could not ordinarily fund, or paying students to work with them at PARC in the summer. They get to make the judgment call. They know that at the end of five of six years, we are going to step back and ask whether this has paid off or not. But there is no peer review. It is really placing the burden on them.

DR. McTAGUE: We have several ways of funding research in universities. One of them is a central fund. Actually, I have a central fund that solicits proposals that must be cosponsored by somebody at Ford, not necessarily in terms of working together, but by someone in operations, research, or advanced engineering saying, “I like the ideas that this person is proposing to work on, and I am going to be the person who acts as an interface with this individual. My name is attached to this in that sense.” We have a group that evaluates these proposals worldwide, which involves people in research—people in all of the technical organizations. We have a concern that this supports work that may be “too obviously relevant.” So there is a separate set-aside of money for riskier, less obvious work about which I personally make the decisions. Then we have other efforts. A local plant may interact with someone who is working on manufacturing engineering at a nearby university; it funds that directly. Sometimes we have a hard time finding out what is going on. We try not to be rigid. We do not want to have a structure inside the company with a checkpoint that you must go through, which could stifle creativity. We have many different ways of funding things that go on in universities, not the least of which is bringing people in for the summer, having graduate students do their theses in our lab, and having professors spend sabbaticals there.

DR. BROWN: Creating overlapping communities.

DR. McTAGUE: And actually, at the other extreme, getting back to education, we also have high school teachers and students spend the summer in the research lab. You have got to do a full spectrum of things.