1

THE BUREAU'S RESEARCH MISSION

|

Public Law 179 (May 16, 1910) Section 2. That it shall be the province and duty of said bureau and its director, under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, to make diligent investigation of the methods of mining, especially in relation to the safety of miners, and the appliances best adapted to prevent accidents, the possible improvement of conditions under which mining operations are carried on, the treatment of ores and other mineral substances, the use of explosives and electricity, the prevention of accidents, and other inquiries and technologic investigations pertinent to said industries, and from time to time make such public reports of the work, investigations, and information obtained as the Secretary of said department may direct, with the recommendations of such bureau. |

Since its establishment by Congress in 1910, the U.S. Bureau of Mines (hereafter “the bureau” or USBM) has had mining and minerals-related research (see box) as one of its major missions. The definition given this mission was deliberately broad, covering everything from research and development related to safety in mines and mills and preservation of workers ' health, to advances in metals and materials. Over the years, the bureau's research mission has evolved as science and technology have changed, so that in its budget justification for FY1995 the bureau states its mission as “to ensure that the Nation has an adequate and dependable supply of minerals to meet its defense and economic needs at acceptable environmental, energy, and economic costs.”

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

For more than 50 years the bureau was a peer of leading universities and research laboratories at home and abroad in its fields of interest, boasting a long list of

research accomplishments. These ranged from coal mining and utilization to the production of refractory and rare metals. In a number of instances bureau research led directly to the initiation of new industries that produced goods as diverse as reactor-grade zirconium, iron from taconite, and gold from ores long thought to be too poor in grade to be economic.

Despite such successes, by the 1970s the bureau had begun to lose ground to more specialized federal research organizations, especially those charged with advancing national priorities regarding defense, aerospace, and energy. Certainly, the bureau could not have undertaken all or even much of this work, but there were significant portions (requiring new bureaucracies and facilities created in other cabinet departments) that could have been performed competently in USBM laboratories. That this did not happen may have been due, in part, to the association of the bureau with an industry—mining—that had a worsening public image. Another reason, perhaps more valid, may be the historical placement of the bureau within the Department of the Interior (DOI). Long a leading department in peacetime, DOI in successive cold war administrations lost ground, not only to other existing cabinet functions but also to new departments and independent agencies. Taken together with the awkward relationship between the bureau's mission to assist in the exploitation of resources and DOI's charge to maintain, manage, and preserve public lands, a decline in the USBM was perhaps unavoidable.

Despite the negative trends affecting the bureau, Congress passed several bills in the 1970s and 1980s that should have had positive influences on its research mission. Among these were the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 (expanded upon in the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977), the Mining and Minerals Policy Act of 1970, the Surface Mining Act of 1977, and the State Mining and Minerals Resources Research Institute Program Act of 1984. This latter piece of legislation is important, as it expanded the so-called mineral institute programs at eligible universities; established a mechanism to coordinate research in federal, state, and private laboratories; and created a Committee on Mining and Mineral Research reporting to the secretary of the Department of the Interior. Congress specified the sectors to be represented on this committee and charged it to, among other things, develop a “national plan for research” on mining and minerals resources topics. The Committee on Mining and Mineral Research was also to recommend to the secretary an annual program to implement the national research plan.

Although the mineral institutes and generic research centers established by this act and related legislation were of some benefit to the universities, the Committee on Mining and Mineral Research found itself in difficult circumstances from the start. For example, its government members rarely supported the concept of the committee, its co-chairman was an assistant secretary of DOI, and its recommendations failed to

garner the necessary political support at department and administration levels. In general, successive DOI secretaries chose to omit funds for the committee's operation, making it a “poor relation” of USBM, on which it was dependent for even routine support services. In response to budget cuts from DOI, the bureau usually omitted requests for appropriations to support the mineral institutes and generic centers as well, and the universities fell into the dubious habit of lobbying Congress to restore the funds. In this respect the bureau and the universities became competitors for parts of what was already a small and shrinking portion of the federal research pie.

From its inception the Committee on Mining and Mineral Research was exempted from the requirement to hold open meetings, as mandated by section 10 of the Federal Advisory Committee Act. While the committee was never particularly secretive about its activities, the Competitiveness of the U.S. Minerals and Metals Industry report 1 contended that the exemption limited public participation and worked against public support for a coordinated federal-academic-private plan for mining and mineral research. It is not surprising that by the early 1990s the committee was increasingly viewed as irrelevant, core congressional support for the mineral institutes had eroded, and the bureau itself had come to believe that, without proper funding and better integration with USBM research, the program should be abandoned.

Any review of the historical context in which USBM operates would be incomplete without mention of the numerous external reviews the bureau and its research programs have undergone. The more recent of these include a series of visitations and reports by the Mining and Metallurgical Society of America 2 and the 1990 National Research Council (NRC) Competitiveness report. In addition, the American Mining Congress's Subcommittee on Technology and Mining Research recently (September 1991-June 1992) visited all the bureau's research centers in a series of information exchanges. The important distinctions that set the present NRC effort apart from previous studies are:

|

1 |

National Materials Advisory Board, National Research Council, National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., 1990, 140 pp. The bureau has implemented all but one of the recommendations in this report; the last of these, an outside advisory committee reporting to the director of the bureau, has been approved and should be in place in early 1995. |

|

2 |

Report on U.S. Bureau of Mines Research Center Visits by the Mining and Metallurgical Society of America Metallurgical Evaluation Teams, letter report to bureau from Mining and Metallurgical Society of America dated February 17, 1988, 6 pp. (also six center specific reports). |

-

The current committee is intended to establish an ongoing system of review and assessment of the bureau's research, similar to that established by the NRC for the Commerce Department's National Institutes of Standards and Technology and

-

The work of the committee is being conducted concurrently with a major “reinvention” of the bureau and reorganization of its management.

These factors make it likely that the current committee's work will have a more lasting impact on the bureau than some previous efforts have.

USERS

The principal user of the bureau's research is the domestic mining industry, defined in broad terms to include not only the production of commodity metals and minerals but also the health and safety of those engaged in the industry, the development and production of advanced metals and materials, and pollution minimization and remediation of environmental damage, from both past and current operations. Less obvious but significant users include the Departments of Defense, Energy, Labor, and Agriculture; agencies such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA); a number of state governments; and a variety of federal activities with interests in trade and foreign relations. The list would be even longer if the bureau's substantial activities in information and analysis were included. As discussed more thoroughly later in this chapter, DOI itself is increasingly becoming a major customer of the bureau's research.

Traditionally, most users of USBM research have had a nonspecific interest, using research results without having a role in the choice of topics and without paying a share of the costs. In other cases, industrial and government users have been able to influence the research directions being taken without paying any costs, and these users have sometimes come to expect pertinent responses from the bureau even though they have not financially supported the work. Where such work is parallel to identified bureau research missions, there is little harm done, but the bureau has been widely and frequently criticized for doing research too narrowly focused on the interests of a single industry segment, a single government entity, or even a single company. For this reason, in an era of declining budgets the bureau has been trying for some time to engage users in cooperative agreements to spread costs, facilitate USBM missions, and improve relevance and the bureau's image among budget makers in Washington.

Until now, the bureau's cost sharing has, in general, been quite favorable to users

in terms of their share of the costs, as well as in whether certain “in lieu” contributions are accepted in place of cash. At the same time, the search for cost sharing has been conducted on a fairly broad front by most USBM research facilities. Under the “reinvention” scheme to be discussed more fully in a subsequent section, this broad emphasis will change. Certain research will be done only if cost sharing can be arranged, while other topics will be recognized as falling within the boundaries of the bureau's national research missions. This is not to suggest that cost sharing in these mission areas will not be sought, but specific research directions may be less open to influence by users.

It is no surprise that traditional mining companies have been slow to avail themselves of USBM research cost-sharing opportunities. What is surprising is that other government entities, state and federal, seldom pay for USBM research that they suggest and even specify. In some cases this is a recognized and desirable means of carrying out federal research missions, as exemplified by relationships such as that between the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) and USBM in the areas of occupational health and safety (as established by the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977). Such arrangements allow the bureau to receive appropriate credit for its work at budget time. In other cases the bureau may be happy to receive partial contributions from governmental partners if the work being performed furthers USBM priorities and therefore might have been done even without partners. Certainly there are many similar instances involving industrial partners who leverage contributions to work that broadly conforms with bureau programs.

Depending on the connection to the bureau's overall mission, costs for a given project might be shared on a sliding scale, although contribution levels as high as the 50 percent now being posited for materials partnerships could lead to a loss of identity for the research as a bureau product. USBM research laboratories are not “job shops,” and they should not be available to do such things as routine analyses and tests that would otherwise be sent to the private sector.

The “reinvention” and management reorganization plans so far available do not propose specific cost-sharing standards bureau-wide, but they imply that the DOI will become an important, if not the most important, “customer ” of the bureau. It is not clear whether certain costs would be shared by sister agencies within the DOI.

EXISTING RESEARCH STRUCTURE

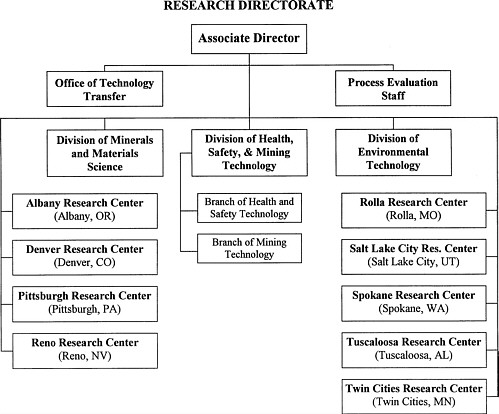

As the USBM presently exists (Figure 1.1), it is headed by a director, who is a presidential appointee, a deputy director (currently a career civil servant but could be a presidential appointment), and three associate directors who are senior civil ser-

vants. The associate director for research manages three major research programs: Health, Safety, and Mining Technology (HSMT); Minerals and Materials Sciences (MMS); and Environmental Technology (ET). Other programs and support activities fall under other associate directors.

FIGURE 1.1 Existing research structure (Source: Draft, U.S. Bureau of Mines Proposed Organizational Structure, by the Organizational Issues Team, August 3, 1994, p. B-18).

Research administration is accomplished through division chiefs in Washington, one for each major program. They operate through nine center directors in the field with the assistance of staff in Washington. The present organization places four layers of management between an individual researcher and the bureau director—namely,

a group supervisor, a research supervisor, the research center director, and the associate director of the bureau. To these should be added one of the three division chiefs and the Washington office staff engineers, who appear to largely control research priorities, project selection, and budgets.

Bureau headquarters, as presently constituted, should have the largest role in establishing broad research directions and goals, measuring progress toward those goals, and making “midcourse” corrections as requirements and budgets change. Yet in this role, headquarters—in the eyes of many bureau researchers—seems remote, arbitrary, noncommunicative, and possibly out of touch with the mainstreams of research. Even without “reinvention” of the bureau, reforms at headquarters are probably overdue.

In the field, at the research centers where research is presently conducted, considerable emphasis is given to the system of “miniproposals ” under which researchers can put forward their own ideas for projects. In practice, however, the miniproposals are handled somewhat differently at different centers, and in Washington they may be accepted, rejected, modified, or sometimes even allocated to different centers. Although modifications are not made unilaterally, researchers can and do feel excluded from the selection process. Here again, the existing system could be modified to help researchers understand it better. Well-defined priorities and goals, clearly communicated from headquarters and center directors, could help channel miniproposals into more fruitful areas.

From the perspective of the individual researcher, there may be too many layers of management in the existing structure. Some researchers noted, however, that competency of research management is a more disturbing issue. A few researchers, in fact, argued that they should be allowed to continuously pursue their own particular specialties, relying on peer review and collegial discourse to link their work with the larger aims of the bureau. It may prove easier to change the bureau's organizational structure than to attempt to change the personalities and skills of the bulk of the people who actually do the research.

REINVENTION PLANS

The National Performance Review initiated by the Clinton Administration in March 1993, had as its aim making the federal government work better, cost less, waste less, and function through a smaller bureaucracy. As directed by the DOI, the USBM conducted a program review that was essentially completed in time for the bureau's FY1995 budget request. Passage of the FY1995 Interior Appropriations Bill by the appropriate House and Senate committees essentially validated the bureau's

program review at the budget and employment levels recommended in the administration's budget request. The bureau's FY1995 budget is approximately $20 million below that of FY1994, and the full-time employee (FTE) level is approximately 211 positions (roughly 10 percent) less.

Implementation of Program Review

The program review and its attendant management reorganization cannot be accomplished in a single year; instead, it is planned for phased implementation extending at least through FY1996. There will be far-reaching effects throughout the bureau, but because the mission of this committee is limited to research, nonresearch effects will be discussed in this report only to the extent they may affect research performance, selection, and quality.

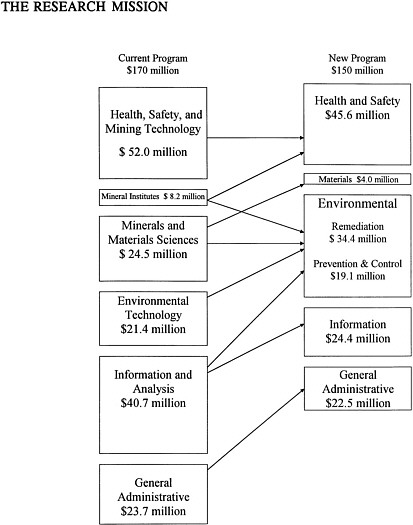

Clearly, the most significant effect on research will stem from changes in research emphasis and resulting budget redirection. By referring to Figure 1.2 and the bureau's written summary of the program review, several inferences can be drawn, including:

-

That health and safety research, which will continue to include some work on safer mining technologies, has its FY1995 budget reduced by about 10 percent and

-

Environmental technology, including both remediation and pollution prevention and control, receives about a 25 percent budget increase after allowances for materials partnerships.

Materials partnerships, the name now applied to the bureau's research on metals and advanced materials, is specifically addressed in the program review. Continuance of this program is made contingent on the availability of matching funds from outside sources, presumably other federal and state agencies as well as industry. Such a 50 percent match is considerably larger than typical match the bureau is able to obtain today and could result in what might basically become contract research. Since materials research is essentially irrelevant to other DOI programs, the tactics being followed in the program review may represent a shift of responsibility for this program, staking its future on outside resources.

The current minerals and materials science program, after removal of materials partnerships, is further reduced under the bureau's program review and redirected to pollution prevention and control. Emphasis is placed on research aimed at extraction, separation, and recycling technologies, provided that such work is primarily related to pollution prevention and control. The program review relegates research on com-

FIGURE 1.2 Changes in the bureau's research program, FY1994 to FY1995 (Source: Reinventing the USBM, Draft Report of the U.S. Bureau of Mines Program Review, December 7, 1993, p. 3).

petitiveness of commodity-specific activities to phased out if not cost shared. This position fails to take into account that most minerals-related pollution arises from the mining, processing, and recycling of a handful of very large tonnage commodities and that the technologies employed are indeed commodity specific.

A further discontinuity arising from the program review's plans for pollution prevention and control research has to do with cost sharing of commodity-specific work for which no federal budgets exist. The program review mentions such cost sharing several times but fails to allow any budgetary flexibility for its accomplishment.

Under the program review, the existing environmental technology program is directed toward remediation almost entirely, and its budget is significantly increased. The new program is expected to work closely with the Abandoned Mine Land Program, and to demonstrate techniques at sites selected with land management agencies, but no mention is made of cost sharing with these other agencies or with industry.

With respect to health and safety, the program review argues that progress toward such goals as removing workers from the most dangerous workplaces would not be accelerated by committing more resources to research and so cuts the budget for such work. The program review also recommends a small cut for occupational health and a much larger one (nearly 20 percent) in programs aimed at short-term gains in worker safety. In the latter case the program review makes specific reference to the bureau's hope for financial help from outside sources and states that USBM should lead in forming partnerships with industry, labor, and the MSHA. Since health and safety research is necessarily a notoriously political area, and one rather far from DOI's core interests, the bureau may have great difficulty in dealing with the subject.

Closures and Consolidations

Research activities at the Rolla (Missouri) and Tuscaloosa (Alabama) research centers are slated for closure during FY1996, together with the Alaska Field Operation Center. Downsizing, albeit modest, is also planned for Washington headquarters and the Denver Research Center. These and other changes are summarized in Table 1.1, Table 1.2, and Table 1.3.

Consolidation of research activities, as set forth in the program review, will begin during FY1995. Although reorganization will not be completed until the end of FY1996 at the earliest, the proposed geographical and management structure of the bureau after its reorganization is shown in Figure 1.3.

Management Reorganization

If the new structure of USBM research is the most important aspect of the bureau's program review, the next most important is the bureau 's management reorganization plan. Referring to Figure 1.3, its most significant features from the standpoint of research include:

-

The Management Council, which will include the seven program directors, four program support directors, the budget director, and the director and deputy director of USBM;

Table 1.1 U.S. Bureau of Mines FTE Levels

|

Facility |

FY1994 Ceiling |

Projected FY 1994 After Buyout |

FY1994 End-of-Year Count |

FY1995 Target |

|

Washington, DC |

494 |

446 |

420 |

403 |

|

Pittsburgh, PA |

374 |

358 |

341 |

367 |

|

Denver, CO |

333 |

331 |

315 |

243 |

|

Amarillo, TX |

208 |

207 |

195 |

192 |

|

Twin Cities, MN |

194 |

188 |

178 |

193 |

|

Spokane, WA |

184 |

188 |

174 |

169 |

|

Albany, OR |

131 |

125 |

117 |

158 |

|

Salt Lake City, UT |

113 |

106 |

98 |

112 |

|

Reno, NV |

79 |

77 |

71 |

79 |

|

Rolla, MO |

70 |

65 |

56 |

0 |

|

Tuscaloosa, AL |

60 |

55 |

44 |

0 |

|

Anchorage/Juneau, AK |

32 |

32 |

31 |

0 |

|

Unallocated |

-- |

-- |

-- |

145 |

|

Total |

2,272 |

2,179 |

2,040 |

2,061 |

|

SOURCE: Letter to Congressman Sidney R. Yates (Chairman, Subcommitteeon Interior and Related Agencies) from Bonnie R. Cohen (AssistantSecretary, Policy, Management, and Budget, DOI) dated May 31, 1994. |

||||

-

the Office of Program Planning and Coordination, charged with developing long-range plans for all current technical programs and candidate long-range plans for emerging issues, coordinating all implementation activities, and monitoring programmatic progress and accomplishments; and

-

the Office of External Affairs, with responsibility for gathering information for a base continuing evaluation of USBM programs.

The Management Council will have responsibility for strategic planning. The bureau's view of how this will operate, as taken from the August 3, 1994, draft proposed organizational structure, is as follows:

In the proposed bureau of Mines organization, the strategic planning process starts with the mission and general goals and objectives which are defined and articulated by the Secretary of the Interior, the Assistant Secretary, and the Director of the Bureau of Mines. The Management Council, which includes the bureau Director, Deputy Director, Office, Division and Center Directors, is responsible for translating that broad guidance into a strategic vision, i.e., program direction for the Bureau of Mines. The Management Council then communicates the strategic vision to all elements of the Bureau of Mines. The Program Centers and Divisions and the headquarters Program Support Offices then develop long-range plans for their activities to be submitted to the Management Council for consideration during the strategic planning process.

TABLE 1.2 Possible U.S. Bureau of Mines FY 1995 Scenariosa

TABLE 1.3 U.S. Bureau of Mines FY 1995 Scenarios (dollars in millions)

|

One-Time Cost of Closure |

|||||

|

Facility |

FY1994 Funding |

Relocation |

Other Costs |

Minimum Cost to Keep Center Open in FY1995 |

Savings in FY1995 with Early Closure |

|

Alaska Field Operations Center |

3.1 |

0.40 |

0.59 |

3.0 |

2.0 |

|

Rolla Research Center |

4.1 |

0.75 |

1.09 |

3.3 |

1.5 |

|

Tuscaloosa Research Center |

4.3 |

0.60 |

1.10 |

3.1 |

1.4 |

|

TOTAL |

11.5 |

1.75 |

2.78 |

9.4 |

4.9 |

|

SOURCE: Letter to Congressman Sidney R. Yates (Chairman, Subcommitteeon Interior and Related Agencies) from Bonnie R. Cohen (AssistantSecretary, Policy, Management, and Budget, DOI) dated May 31, 1994. |

|||||

The Management Council concept will be extended to program centers, divisions, and field offices, as shown in Figure 1.3. This structure is intended to link program managers with the directors, who themselves provide the next up-link to the Management Council itself. The necessary down-links are still being developed, and details of the management substructure are not available at this time.

It should be made clear that the bureau's new management structure is still undergoing internal review, and its final form may not be available and approved until late 1994. In particular, the role of the Office of Project Planning and Coordination is still open to considerable debate. The questions of how research priorities will be established and projects agreed upon also are unanswered.

Future of the Mineral Institutes Program

While the intent of program review is to phase out the mineral institutes program, including the generic mineral technology centers, over five years, the bureau recognizes that some of the university research is both worthwhile and consistent with USBM's new research priorities. Accordingly, the bureau could replace some of the program with specific research contracts at selected institutions. Univerity-based research would be drawn closer to the bureau and its research priorities and would be funded by and more closely coordinated with the bureau.

Research Partnerships

Just as reinvention of the bureau is in line with the administration 's National Performance Review, so too should its research partnerships be in line with the aims of the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) of making industry a full partner, and even the leader, in such partnerships. It is unreasonable to expect funding comparable to that available for industry partnerships through the committee on Civilian Industrial Technology (CIT). The CIT, one of eight NSTC committees, is chartered with ensuring close communication with industry, designing federal technology programs to meet industry goals of improved profitability and global competitiveness, and focusing on critical industry sectors. Mining and minerals are not ordinarily considered parts of the manufacturing, electronics, or advanced materials industries on which CIT concentrates, but there are other NSTC committees that reflect the missions of DOI and the bureau and on which both organizations are represented. Progress is being made: a draft memorandum of agreement linking USBM and DOE national laboratories has been prepared, and contacts with industry are being expanded. There are even hopes that, under the umbrella of NSTC, the EPA may join the federal group.

USBM's program review contemplates research partnerships in several different forms. In the first of these, covering materials, it is stated that work will continue only if 50 percent cost sharing is achieved. In another, partnering is expressed in the form of a hope that outside sources, presumably other agencies as well as industry, may be willing to make up budget shortfalls. Finally, there are references to partnerships in areas such as pollution prevention and control but without specific budget allocations to cover the USBM share. This latter can, of course, be made good if there is sufficient flexibility in bureau budgets or if funds can be redirected into partnerships.

Considering the very low levels of partner contributions so far achieved by the bureau, it is difficult to criticize any lack of emphasis on research partnerships in the program review. There is, however, another factor that may work against partnerships and that concerns the relationship between DOI and the bureau. The program calls for “relevance” of USBM programs to the aims and missions of the department, and that is entirely as it should be. Indeed, DOI includes several agencies that have special need for the expertise and facilities of the bureau. At the same time, this makes DOI a “customer” as well as proposer of the bureau 's budgets. This could result in DOI and its other agencies having a preferred position, with the potential for “squeezing out” other potential partners.