APPENDIX C

REPORT OF THE PANEL1 ON FACILITIES AND RESEARCH AT THE RENO RESEARCH CENTER

FACTUAL DATA ON THE RENO RESEARCH CENTER

The Reno Research Center (RERC) was created in 1920 by moving a center originally in Denver and then at the Colorado School of Mines in Golden to the campus of the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR). The original building (7,500 ft2) was supplied by the university, and the program largely involved rare and precious metals. In 1954 a new building (63,000 ft2) was constructed adjacent to the UNR campus. The current staff, after some reductions in the past few years (from a high of 100), has 79 members, including 48 scientists and nine UNR students. In contrast to the Salt Lake City Research Center (SLRC), the RERC' s most recent director did not hold an adjunct appointment at UNR but did serve on the Advisory Board of the Mackay School of Mines and on the research council of the Generic Center for Mineral Industry Waste Treatment and Recovery. A healthy fraction of the bureau staff attends classes at UNR, either in pursuit of degrees or as continuing education.

The programs of the RERC have changed substantially over time. For some 30 years or more, starting with the Zadra cell for electrolytic refining and the ability to recycle activated charcoal for gold recovery, through the development of processing techniques for refractory gold ores, the heap leaching concept and the methods for agglomeration with cement, the U.S. Bureau of Mines was the single most important contributor to the increase in Nevada's gold production by a factor of 30 or so in the past 15 years. (Nevada produces approximately 60% of U.S. gold.) A recent policy

|

1 |

The Panel on Facilities and Research at the Albany Research Center consisted of the following committee members: Harold W. Paxton, Panel Chair, Carnegie-Mellon University; Robert Ray Beebe, Tucson, AZ; Donald C. Haney, University of Kentucky; Frederick C. Johnson, National Institute of Standards and Technology; Dale F. Stein, Michigan Technological University; and Jonathan G. Price, NRC staff. In addition, Sharon K. Young (Magma Copper Company) participated as a guest panelist. |

decision to cut back on work in this area has meant fairly drastic changes in the research program to emphasize biotechnology and pollution prevention and control.

Although a full evaluation was not possible, the panel had some doubts as to how well all the current RERC staff have been able to adjust to new areas and in particular to be fully aware of relevant work elsewhere. Some new hires have helped, although the quality of the new personnel is not as high as the director had once hoped (a “ world-class” scientist who was being recruited declined for family reasons). An increased budget for training has helped but is still somewhat marginal.

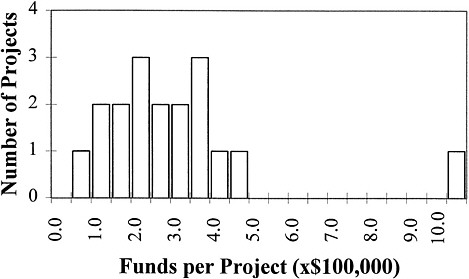

The RERC's budget for FY1994 is $5.39 million (including some funds from outside the bureau), which is not significantly different from FY1991-1993 but only because of the injection of certain one-time funds; FY1995 may well be very strained. Minerals and Materials Sciences (MMS) remains the largest contributor with 67% and Environmental Technology (ET) provides 30%. A small project comes from Health, Safety, and Mining Technology (HSMT) and the remainder comes from a variety of sources, including CRADAs. This budget supports 18 major projects (Table C.1), ranging from $50,000 to $1,000,000 in FY1994 funding, with an average size of $281,000 (Figure C.1).

Under the “Reinventing the USBM” plan, the RERC will be a satellite to the “Pollution Prevention and Control Center” at SLRC. The exact plan is not final at this time, and the resulting uncertainty cannot be good for morale, although employees made few explicit comments to the panel. In discussions with working scientists they were much more positive than SLRC employees in acknowledging receipt of feedback on proposals from the bureau's Washington headquarters.

RESEARCH PROGRAMS

Historically the RERC has been dedicated to metallurgical and materials processing. In the past several years, however, the center has taken upon itself development an internal strategic plan, which is a reorientation of the original focus of the center's research. Development of the RERC plan was independent of bureau headquarters, which developed the program review document with little or no input from the RERC director's staff. The RERC is to be commended in taking the initiative of developing a strategic plan that has a mission statement, goals, objectives, and approaches to achieving these. Obviously, implementation of the strategic plan will require time, but important first steps have been taken.

In the current organizational structure at the RERC, research projects are organized into two divisions—Metallurgical Processing and Chemical Processing

Figure C.1 Funding for Reno Research Center projects, FY1994.

(Table C.1). These appear to be somewhat arbitrary divisions because there are projects that could just as readily be placed in either division. The project division was based sometimes on the reporting desires of certain researchers; in other cases projects were placed in a division to balance the funding. Currently, the projects are not organized programmatically.

On the basis of project objectives and summaries provided to the panel, it is evident that there is no overall coherent programmatic approach. For example, projects such as “In-Place Leaching Chemistry ” and “Thiosulfate as an Alternative to Cyanide for Refractory Gold Ores, ” both of which are in the Chemical Processing Division, are closely related to several Metallurgical Processing Division projects, such as “Heap, Stope, and In Situ Leaching Lixiviants” and several tasks of the project “Fundamental and Applied Aspects of Mineral Bioprocesses.” The research director at RERC is aware that the projects are not categorized programmatically and the intent of the RERC Strategic Plan is to change this.

As at SLRC, the methods used by the bureau appear to be counter to developing programmatic approaches at its research centers. Proposals are submitted by staff researchers from the centers to the three headquarter divisions (ET, MMS, and HSMT). The current method of project selection is conducted at headquarters with inadequate communication or input from the centers, leading to poor overall programmatic focus. The problem is further compounded when project funding comes from

TABLE C.1 Research Projects, FY1994, Reno Research Center

|

Divisiona |

|||||

|

Minerals Research ($3,369,000; 24.9 FTEs) |

|||||

|

Fundamental and Applied Aspects of Mineral Bioprocesses |

MET |

||||

|

Purification of Aluminum Scrap |

CHEM |

||||

|

New Solvent Systems for Recycling Advanced Materials |

CHEM |

||||

|

Thiosulfate as an Alternative to Cyanide for Refractory Gold Ores |

CHEM |

||||

|

Recovery of Ancillary Metals from Mill Tailings |

MET |

||||

|

In-Place Leaching Chemistry |

CHEM |

||||

|

In Situ Leaching–Solvent Investigations |

CHEM |

||||

|

Hyperaccumulator Farming/Mining of Cobalt and Nickel |

MET |

||||

|

Anode Reactions to Decrease Energy Consumption |

CHEM |

||||

|

Recovery of Platinum-Group Metals from Catalytic Convertersb |

CHEM |

||||

|

Environmental Technologies ($1,495,000; 12.3 FTEs) |

|||||

|

Effective Closure Methods for Metallurgical Processing Operations |

MET |

||||

|

Chemical Treatment of Wastewater |

MET |

||||

|

Advanced Leaching Systems for Detoxification of Lime Sludge |

CHEM |

||||

|

California Mine Seal Assessment |

MET |

||||

|

Natural Minerals for Wastewater Treatment Systems |

CHEM |

||||

|

Extractive Metallurgy of Wastes |

MET |

||||

|

Treatment of Midnight Mine–Acid Mine Drainage Water |

MET |

||||

|

Environmental Impacts of Backfill–Cyanide Fatec |

MET |

||||

|

Western Arctic Coal–Drainage Qualityd |

MET |

||||

|

Health, Safety, and Mining Technology ($200,000; 1.6 FTEs) |

|||||

|

Lixiviant Development in Stope Leaching |

CHEM |

||||

|

Heap, Stope, and In Situ Leaching Lixiviants |

MET |

||||

|

a At the RERC, projects are managed under one of two divisions: Metallurgical Processing (MET, with 22.7 FTEs) and Chemical Processing (CHEM, with 16.1 FTEs). b Completed in 1993. c Conducted in conjunction with the Spokane Research Center. d Conducted under Cooperative Agreement with Arctic Slope Regional Corporation and Arctic Slope Consulting Group. |

|||||

the three separate divisions, each with seemingly overlapping program objectives, review of proposals, and selection of the projects for funding. Examination of titles, objectives, and summaries of RERC projects indicates that in some cases there is very little difference between projects funded by ET and MMS, for example. This suggests that (1) there is little communication among division chiefs or among Washington office staff engineers from the three headquarter divisions and (2) there is no overall mission that is being adhered to in terms of research goals and objectives.

A project selection process that involved the chief of each headquarters division and the center directors could eliminate this overlap of project funding and lead to a better programmatic approach for research at the centers. This would have the additional benefit of eliminating a layer of management at headquarters, which would simultaneously release more funds for research and streamline the proposal selection process. The current oversight of projects by the Washington office staff engineers also appears to result in micromanagement of small projects.

The panel reiterates that the bureau could benefit from an external advisory group consisting of users of bureau technology and other stakeholders including, especially for RERC, land-use and mined-land reclamation organizations. The advisory group could assist in maintaining a focused bureau mission as well as guiding and understanding the bureau's overall programs.

On a positive note, the RERC is to be commended for implementing and evaluating the Self-Directed Work Team (SDWT) concept. This is a powerful mechanism for improving morale and efficiency. If SDWT were coupled with a programmatic approach that allowed redirection of funding to successful projects, the panel believes the centers could generate work products of higher technical quality. SDWT would have the added advantage or removing another layer of management, thereby releasing funds for additional research.

The lack of a programmatic approach to research by bureau headquarters has resulted in fragmented funding of short-term projects that are inadequately developed for application by user groups. Grouping projects into a focused program at the centers where the research directors have authority for moving funds would have several advantages:

-

different approaches to solving a problem could be evaluated simultaneously;

-

communication among researchers would be enhanced, resulting in higher-quality work;

-

the merits of each approach could be evaluated annually;

-

funding could be reallocated to successful approaches, and unsuccessful approaches to solving a problem could be abandoned at the discretion of the center director; and

-

economic considerations for technology implementation by users could be used as one of the criteria for selecting one project over another.

In some research areas, perhaps most notably in biotechnology, which is a thrust area that was initiated in metallurgical processing and environmental technology in the late 1980s, it is questionable that RERC has qualified people to successfully direct the current staff in this leading-edge research program. RERC searched nationally for a world-class researcher several years ago but failed to attract or acquire the services of an individual with the credentials and qualifications to initiate and accomplish credible research consistent with the center's objectives to strive for research excellence. The failure to attract such an individual is a real handicap to RERC 's sincere commitment to do quality work.

The relevancy of bureau research projects to the end users at times is questionable. Because there is apparently no direct feedback by technology users to the Washington office staff engineers, who select projects, there is a danger that projects selected for funding are irrelevant to user needs. Currently, interactions with technology users appear to be limited to researchers at the bureau's centers. Whereas this interaction is highly commendable and should be encouraged, this personal contact is likely to occur only with those researchers who actively enjoy these types of interactions; not all researchers have the personality to communicate freely with users. The panel stresses that more formal mechanisms for interactions with technology users need to be implemented. Closely tied to the selection of relevant research programs and supporting projects is distribution of information to potential users. There is strong evidence that technological results are not reaching potential users. To get timely and relevant feedback from users and to enhance the dissemination of bureau-generated information, the bureau researchers need to actively participate at industrial association and interagency workshops, task forces, and committees. Specific examples include:

-

the California Mining Association Environmental Committee,

-

the USGS Mine Drainage Interest Group, and

-

the EPA committees and task forces on environmental issues related to mining (e.g., revision of the leach test for solid wastes and sediments).

Similar committees and task forces exist for environmental concerns and metallurgical processing within the Nevada Mining Association, Northwest Mining Association, Colorado Mining Association, New Mexico Mining Association, and other organizations.

FACILITIES, SUPPORT, AND STAFF

The RERC is located at a convenient and excellent 4.5-acre site on the edge of the UNR campus. The 57,000 ft2 facility was expanded to 63,000 ft2 in 1994. The building is clean and well maintained. The panel found the facility to be appropriate for the research activities being conducted. It provides a good working environment and adequate laboratory space for the present level of research.

Research equipment is fairly modern and well maintained and appears to be adequate for current research programs. Relatively modern analytical equipment includes atomic absorption spectrophotometers, inductively coupled plasma (ICP)-atomic emission spectrometers, x-ray diffraction and x-ray fluorescence, and a scanning electron microscope. Continuous acquisitions and upgrading of equipment are occurring (based on a bureau-wide plan for the purchase of expensive analytical equipment). An ICP-mass spectrometer is being obtained for use at the RERC.

Support in the areas of secretarial services, drafting and graphics, and technicians seems adequate to serve needs. A technology transfer team of two engineers who are each devoting about 50% of their time on a temporary basis has been appointed. Should the RERC become a satellite of the SLRC, as planned, this function could be managed for the RERC by the SLRC.

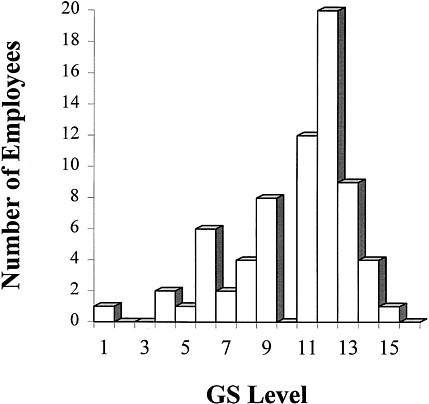

The Reno Research Center has a total staff of 79 persons, 48 of whom are scientists or engineers. As shown in Figure C.2, the range in grade is GS-1 to GS-15, with approximately 50% of the permanent staff at the full performance level (qualified to be a principal investigator on a research project at GS-12 or higher). This distribution of persons appears generally adequate to accomplish the mission of the RERC, although the weaknesses mentioned above might suggest the need to recruit two or three senior researchers as opportunities arise.

The center's mix of employees is provided in Table C.2. The largest groups of technical personnel are chemical engineers and chemists. In view of the research being conducted at the RERC, a preponderance of persons with these backgrounds would seem appropriate.

The ratio of researchers to supervisors and managers is 2.2 to 1. By industry standards, this ratio is out of balance. A ratio of 10 to 15 is common in industry. With a reduction in the number of supervisors, more personnel would be available to conduct research.

The ratio of researchers to technicians plus tradesmen is 7.6 to 1. This ratio is also out of balance by industry standards. Commonly, one technician per researcher is present in some industry research laboratories.

The ratio of researchers to administrative staff (clerical support staff and managers) is 4.0 to 1. This is a ratio that would be found in many research organizations.

Figure C.2 Distribution of general schedule grades of RERC employees.

Table C.2 Disciplinary Backgrounds of RERC Employees

|

Number |

|

|

Technical Staff |

|

|

Chemical engineer |

22 |

|

Chemist |

16 |

|

Physical scientist |

4 |

|

Metallurgist |

3 |

|

Biologist |

2 |

|

Geologist |

1 |

|

Support Staff (includes computer specialists, technicians, and tradesmen) |

10 |

|

Students |

9 |

|

Administrative Staff |

12 |

|

TOTAL |

79 |

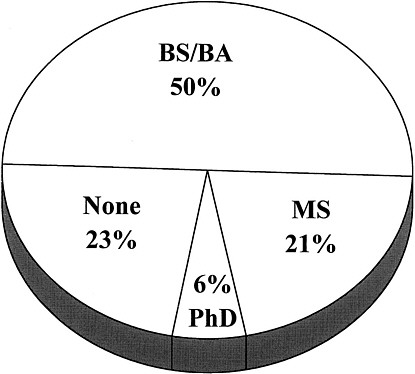

Figure C.3 Distribution of highest degrees held by RERC employees.

The distribution of highest degrees held by RERC employees is given in Figure C.3. As shown, about 27% of the employees have advanced degrees. Among GS-12 and higher employees, 45% have advanced degrees. This distribution of degrees is generally appropriate for the applied research that is being conducted.

TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER

Several mechanisms are used for the transfer of technology developed by the RERC. These include internal publications, Reports of Investigations, Information Circulars, publication of journal articles and proceedings papers, patents, open industry briefings, short course training, and presentations at technical meetings.

The Internet has just been introduced into the RERC, and personnel at the center are becoming more familiar with electronic communication. Ultimately, users in in-

dustry, academia, and government will have access through the bureau 's Gopher to bimonthly lists of publications, the Technology News letters, Technology Transfer updates, and information on CRADA opportunities and all areas of bureau research.

Table C.3 Number of Publications and Presentations, October 1990 to June 1994

|

Transfer Mechanism |

Number |

|

Report of investigation |

15 |

|

Information circular |

0 |

|

Peer-reviewed journal paper |

6 |

|

Proceedings paper |

27 |

|

Oral presentations |

77 |

|

Open industry briefing |

4 |

|

Patent |

1 |

To assess the use of the various mechanisms of technology transfer by the RERC, oral presentations and written publications were analyzed. These data are provided in Table C.3. From this information it is apparent that major emphasis has been placed on technology transfer through oral presentations. While this is valuable, it should not be done at the expense of permanent recording of technology. As can be noted, in this nearly four-year time period, a combined total of 48 bureau Reports of Investigations and outside publications were published, with over 50% being papers in symposium or conferences proceedings A downside of publication in proceedings volumes is the limited audience that has access to these publications. It is strongly urged that greater emphasis be given to publishing in technical journals and bureau Reports of Investigations.

With regard to the number of papers published, 28 research scientists published these 48 reports and papers between October 1990 and June 1994. This amounts to about one publication every two years per researcher. This is far from adequate for full time researchers.

USER COMMENTS

Five users or potential users2 with the bureau discussed with the panel their thoughts about the bureau's research programs. The comments below have been aggregated rather than attributed to specific people.

Cooperation by relevant parties with bureau researchers is generally fine, especially at the researcher-to-researcher level. Cooperation at a higher level is not always good (e.g., between higher levels in the USGS and the Bureau of Mines). The panel believes that, in particular, there should be more communication between the bureau and the USGS on the status of activities in mining-related areas, especially in work on acid mine drainage, mine dewatering, and pit-lake chemistry.

The external scientific and engineering community (outside the Bureau of Mines), either in industry, other parts of government, or academia, is not normally involved in the review of bureau work, except for review of those manuscripts that bureau researchers submit for publication in refereed journals. This external community is rarely involved in review of internal bureau publications (Reports of Investigations, Information Circulars, etc.), review of miniproposals or proposals for research (even informally), or review of ongoing work (except perhaps by CRADA partners). The panel believes that the bureau should involve the external scientific and engineering community more in the whole process of internal bureau research, from communication before miniproposals are submitted, through communication of preliminary results, to peer review of bureau publications.

The bureau is too limited in its travel policy. Its interpretation of the Department of the Interior's policy limiting total travel to any particular technical or professional meeting to $5,000 is a severe limitation on technology transfer capabilities and on professional development, because so much of what the bureau does is applicable to a few key professional meetings (e.g., Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration; The Minerals, Metals, and Materials Society).

The better students graduating with B.S. degrees tend not to go to work for the Bureau of Mines, except under extenuating circumstances (such as when a spouse has a job in the same town as a bureau research center). This is largely because salaries for entry-level employees at the bureau are considerably lower than those available

|

2 |

The following guests participated in discussions with the panel: Thomas Fronapfel, chief, Bureau of Air Quality (former chief, Bureau of Mining Regulation and Reclamation), Nevada Division of Environmental Protection, Carson City; James Hendrix, dean, Mackay School of Mines and director of the Generic Center for Mineral Industry Waste Treatment and Recovery, University of Nevada, Reno; Robert Blank, soil scientist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Reno; Carol Boughton, hydrologist, U.S. Geological Survey, Water Resources Division, Carson City; and Robert Vicks, chemist, Nevada State Health Laboratory, Reno. |

in industry. Graduates with a B.S. degree in relevant engineering fields are currently being offered $36,000 to $42,000 per year by industry.

CONCLUSIONS

-

The project selection system in its present form distorts the ability to carry out research effectively, especially at the smaller bureau centers such as RERC. If the projects selected indeed originated from the center, this is not so bad, but if a program is assigned from the Washington office, the availability of skilled and knowledgeable people may be stretched beyond reason. A project selection process that involved the chief of each headquarters division and the center directors could eliminate this overlap of project funding and lead to a programmatic approach for research at the bureau's centers. This would have the additional benefit of eliminating a layer of management at headquarters, which would release more funds for research and streamline the proposal selection process. The panel recognizes that changes in this direction are being considered by the bureau.

-

Communication between the bureau and other government agencies (EPA, USGS, etc.) is very spotty. In many cases this causes redundant or misdirected activities. A similar situation exists with mining operators and industrial associations. A concerted effort from all levels of the bureau would produce a quick payoff.

-

The panel believes that the bureau should involve the external scientific and engineering community more in the whole process of internal bureau research, from communication before miniproposals are submitted, through communication of preliminary results, to peer review of bureau publications. A formal mechanism to include more external reviewers in the program definition would help to maintain relevance and standards. It would also serve to improve communication on bureau projects and may attract more tangible interest in CRADAs and other cooperative efforts.

-

The RERC director appears to try to get people to professional meetings where they can interface with a broader group, but the established policies of bureau headquarters (and the Department of Interior) are often self-defeating in this area.

-

Personnel policies cause the quality of new hires to be marginal in too many cases. The regional characteristics noted at SLRC are also present at RERC; some of this is desirable and unavoidable, but a leavening of people with other backgrounds is essential. Few make it (or are likely to) through the recently installed peer review system, and thus the system itself loses credibility, especially the concept of a dual-ladder advancement system. If a better set of role models were available to everyone, the expectations would be clearer. As a minimum, there should be a cadre of people

-

who could earn tenure at a good university. This is true of many government labs, but so far the panel has seen few at the bureau who would qualify. The bureau may be well advised to look for people at government laboratories that are candidates for downsizing even though many candidates might not be familiar with problems in the mining industry.

-

The panel believes that greater emphasis needs to be given to publishing in technical journals and bureau Reports of Investigations. The panel received a long list of publications by RERC researchers, from which it appears that only six were in peer-reviewed journals. Six peer-reviewed papers from 48 scientists and engineers in nearly four years is not adequate performance.

-

The development of the annual program from individual suggestions permit many good ideas to be made. However, the broader strategic issues cannot be developed by this process, and in too many cases miniproposals are submitted in a vacuum. Much greater use could be made of the center directors in the development of their program; they are the most experienced in the needs of their “customers” and know the capabilities and limitations of their staffs. If there is a serious desire to eliminate two layers of management (an idea with which the panel concurs), the staff engineers would then be unnecessary. (If some training purpose were served with this as a rotating position for a couple of years, without the management function, this may be desirable. The panel does not yet have adequate information to make a judgment). The second layer of management could come by increased use of self-directed teams. The initial efforts with these in Reno are encouraging and once the concept is accepted, it could be a real plus for the bureau as a whole. The panel also urges that more discretion be granted to center directors in reprogramming funds during a fiscal year—perhaps 10 to 20% of the budget as factors change with successes and problems. They are in the best position to make adjustments.