Development and Diffusion of Medical Technology in Europe

Annetine C. Gelijns and Kathleen N. Lohr

In the previous chapter, Jan Blanpain has presented a thought-provoking picture of the evolution of European health care systems. His remarks indicate how widely health and health care still vary in a European continent that is steadily, although hesitantly, moving toward greater homogeneity in politics and finance. Consider, for instance, the variation in health patterns: Middle-aged Northern Europeans are three times more likely to die from coronary heart disease and cancers than their European counterparts in the south. By contrast, liver cirrhosis and traffic accidents tend to dominate mortality statistics in all of southern Europe. In a cultural sense, indeed in terms of health and disease in day-to-day life, one is struck by the deep contrast between Henrik Ibsen's world of the north and the very different world of Federico Fellini in the south. Despite such diversity, European health care systems are similar in some fundamental respects. Moreover, with the inclusion of health as a formal responsibility of the European Commission in December 1991 at the Maastricht Summit, these similarities will no doubt increase.

In this commentary, we consider some of the implications of Jan Blanpain 's observations specifically for medical technology and medical innovation. In particular, we address two key questions. First, how does health care in Europe affect the diffusion of medical interventions, the assessment of medical technologies, and the propensity to generate new interventions? Second, to what extent is the European experience relevant for the United States? Unfortunately, very little cross-national research moves beyond the more general comparisons of health care sys-

tems. As a result, this response is more exploratory and tentative than based on systematic analysis.

How should we look at technological change in the European context? Historically and politically, most European nations define health care as a social good; they reject individual ability to pay as a means for rationing health care. This is reflected in the fact that all European governments that were members of the Council of Europe signed the 1961 Social Charter of Turin, which codified the public obligation of the state to provide health care. Subsequently, the majority of European nations have incorporated health care as a human right in their constitutions. Thus, they provide universal access, rely on public finance to a much greater extent than does the United States, and focus on systemwide interventions or macromanagement. 1

Table 1 shows that Europeans use public planning and regulatory tools to provide, limit, or distribute the supply of health care resources (i.e., hospital facilities, advanced medical technologies, and medical personnel). Demand-side strategies include publicly determined global budgets for hospitals and legally binding fee schedules for those providers who are compensated on a fee-for-service basis. As Uwe Reinhardt has observed, such public macromanagement differs from the American tendency to micromanage physicians and patients, especially in the private market, through both fine-tuned financial incentives and direct interventions in clinical decisions.2

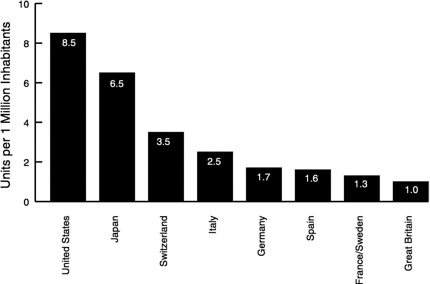

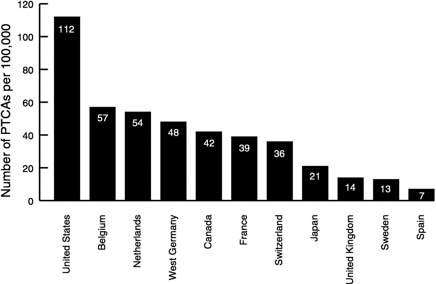

What are some of the consequences of the difference between macromanagement and micromanagement for the diffusion of medical technology in Europe and the United States? Figure 1 and Figure 2 and Table 2 show

TABLE 1 Alternative Cost-Containment Strategies in Health Care

|

Strategy |

Micromanagement |

Macromanagement |

|

Supply |

Encourage efficiency in production of medical treatments through economic incentives Put legal constraints on ownership of health care facilities |

Plan and regulate health care resources |

|

Demand |

Convert patients to consumers through cost sharing |

Set global budgets for hospitals and expenditure caps for physicians |

|

Market as a whole |

Supervise decisions of doctors and patients |

Use price controls |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Reference 2 |

||

TABLE 2 Pharmaceutical Consumption in the European Community, 1987

large international variations in the use of three kinds of technology. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a form of capital-intensive equipment; its diffusion per population demonstrates a better than eightfold difference between the United States and the United Kingdom. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) is a common clinical procedure, yet utilization rates are stunningly different. Pharmaceuticals present an even more complex situation.

In short, the available data suggest that Europeans probably consume more pharmaceuticals than Americans but that in general, Europe has less capital-intensive equipment and lower utilization rates for surgical procedures than the United States.5,6 Importantly, these same studies also show that these variations across the Atlantic cannot be explained by differences in disease prevalence.

What factors, then, do play a role? The answer is not clear. Clinical uncertainty is definitely important; it may be reasonable to assume for the moment that such uncertainty is more or less equal on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Cultural variables, including patient preferences and physician attitudes, should not be overlooked. In Denmark, for instance, liver and heart transplantations were not introduced until 1990 because the criteria for brain stem death were not accepted until then.7 Medical

tradition, of course, is another factor. With Russia again in Europe these days, one might reread Anton Chekhov's short story “A Case of Medical Practice ” to glimpse the power of tradition. Moving a bit more toward the West, we now know that the German and English medical communities perceive the etiology of cardiovascular disease very differently. 8 This difference in perception results in large variations in the use of cardiovascular drugs as well as in medical innovation. For example, it is no coincidence that beta blockers emerged in the United Kingdom, whereas calcium channel blockers found their origin in Germany. Beyond cultural variables and medical tradition, the specific character of the health care system is another critical factor. In other words, one must understand the ramifications of the way in which countries manage the supply of health care resources, including technology, and the demand for medical interventions.

On the supply side of the equation, European governments strongly influence the supply of medical technology, either indirectly or directly. With regard to indirect effects, medical technology, hospital capacity, and personnel are closely interrelated. For example, the introduction of amniocentesis and other prenatal tests required an infrastructure of genetic centers and specialized personnel. Once these centers, geneticists, and lab technicians were in place, they created demand for the use of their technologies. Thus, the deliberate mechanisms that European nations use for planning the need for medical personnel as well as facilities exert a strong indirect influence on the use of technology.

With regard to direct interventions, Europeans regulate the introduction of drugs and devices, although perhaps not as rigorously as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States does. With the possible creation of a European FDA—as its opponents call it—and a process of so-called binding mutual recognition, the dynamics of product development will undoubtedly change considerably.5 In addition to these existing and future premarketing controls, many European countries now require hospitals to obtain a public license for expensive devices and procedures, such as neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and genetic screening. In general, these supply-side mechanisms are directed chiefly at high-technology interventions.

Even as far back as the 1970s, policymakers began to realize that focusing mainly on high technology could be misleading, as the more commonly applied technologies often had equal or more significant effects on health care costs. In the 1980s, therefore, European nations began to pay particular attention to how their payment systems affected the demand side of the equation. For example, as Jan Blanpain has observed, The Netherlands, France, and Germany introduced elements of budgeting systems for hospitals or for ambulatory care physicians. Nations with

national health systems, such as the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Spain, already had global budgets at the national or regional level. These budgetary caps have an interesting characteristic: they have provided a framework that forces choices among technologies. In the United Kingdom, for instance, decisions on capital spending occur at the regional level. That is, National Health Service administrators may have to decide whether to buy an MRI for one major center or to purchase fluoroscopic radiographs for, say, seven district hospitals, and this says nothing of the trade-offs between diagnostic and therapeutic technologies that they must make. These trade-offs have succeeded in dampening the overall rate of diffusion. Similar results were observed in New York State, where an experiment in hospital budgeting showed that ceilings on operating and capital costs decrease diffusion, whereas an all-payer diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) scheme with capital pass-through promotes the duplication of technology.9

Yet, budgets by themselves do not mean that the most effective or cost-effective technologies are necessarily in use. In a recent volume of Medical Innovation at the Crossroads, Alan Williams argues that a prerequisite for the rational allocation of resources within a fixed regime is information on the relative effectiveness and costs of medical interventions.10 In practice, this detailed information is not available. Consequently, medical and professional priorities often drive the system without overt regard for cost. According to Williams, concerns about costs are left to managers in health authorities or hospitals, who, because they have little information, make rather arbitrary decisions about increasing or decreasing capacity to balance their publicly set, fixed budgets.10 In short, at the heart of the priority-setting process is the information void that Jan Blanpain discussed in the previous chapter.

Moreover, many European health authorities have concluded that budgetary systems may not necessarily contain serious incentives for efficiency. These deficiencies have led Europeans to scan the U.S. health services horizon and borrow U.S. concepts. For example, the United Kingdom and The Netherlands recently introduced elements of managed competition in an attempt to increase efficiency without reducing equity. The general idea is that providers will compete with each other for contracts from health authorities or the sickness funds and that they will choose the provider that offers the best deal. This requires these purchasers of care to assess the needs of the populations that they cover and the performance of providers, which leads us back to that information void.

Consequently, almost all European nations have begun to invest more heavily in technology assessment, outcomes research, and the like. This is reflected in new European Community programs from Brussels and the many new national assessment organizations across Europe. An in-

teresting example, in which assessment activities have been directly linked to the reimbursement process, can be found in The Netherlands. The Dutch Sickness Funds Council, the Department of Health, and the Ministry of Science and Education have established a fund to support cost-effectiveness research of certain technologies, and such research has been classified as a precondition for their eventual inclusion in the benefits package. The resulting assessments, for instance, influenced the Sickness Funds Council to cover heart transplantation but to exclude liver transplantation from coverage.

So much for some current changes in the management of European health care and their likely impact on the diffusion and assessment of medical technology. Taking a longer view, these changes will self-evidently affect the evolution of technology or medical innovation. Constraints on the diffusion of certain technologies and price controls might reduce economic incentives for innovation. Of course, the decision to invest in research and development depends not only on the marketability or demand for new technology but also on advances in knowledge. This means that both the size and the quality of the local scientific community are essential to innovation. In this respect the United States has a real advantage over Europe. For example, the United States is more prolific in terms of publications and citations than the entire European Community.5 Moreover, one could argue that the cultural propensity to innovate is stronger in the United States.

Because insight into the factors driving medical innovation is especially weak, two questions deserve examination. First, which continent stimulates a higher rate of medical innovation? One would expect the answer to be the United States. Still, one should bear in mind that some European countries have successfully implemented public policies to counterbalance the innovation-suppressing effects of excessive regulation. For example, it is well-known that most Europeans regulate their drug prices, as shown in Table 2, but it is less well-known that the British National Health Service and the French Government retain explicit incentives for innovation in their pricing formulas. The second question concerns the direction of innovation. Has the cost-consciousness of European nations stimulated a focus on the development of cost-effective technologies as explicit research and development targets? It is instructive to note that laparoscopic cholecystectomy, PTCA, and the lithotriptor, which all provide alternatives to costly major open-surgery procedures, originated in Europe.

In conclusion, Europe, if you like, by now has 44 states and a population of more than 600 million. The United States has 50 states and a population of more than 250 million. The European trends that Jan Blanpain described, and especially the implications of these for medical

innovation and diffusion, can be relevant to the United States. They provide the United States, both the “united” part of it and each of the states themselves, with an unprecedented set of examples of different macromanaged systems and their effects on medical technology, health outcomes, and expenditures. When new experimental health care structures are contemplated—and as we know, many are being contemplated at both the state and federal levels of the United States—no better public laboratory exists than the many states of Europe. They can document a wide variety of potential solutions and their proven benefits and drawbacks. A much greater level of interaction, however, would be needed between the federal and state agencies of the United States on the one hand, with at least a couple of European countries and the European Commission on the other, to render such contacts productive in terms of new concepts and initiatives.

Of course, the United States can be of great value to many European systems as well. Much of the information and data that are often so dramatically lacking in Europe can be foundin the United States. Europeans, for example, can learn tremendously from the many research initiatives in outcomes, clinical practice guidelines, and health status assessment now being conducted in the United States. Also, the lagtime of Europe's learning from the United States could be significantly shortened if a more intensive interaction across the Atlantic were to materialize.

A final note of caution: The differences that we outlined are not without roots; the evolution of micromanagement structures in the United States, and macromanagement systems in Europe did not occur in a vacuum. Although the two sets of societies may look alike in many ways, their fundamental premises may be very different. It is beyond the scope of this response to elaborate this point, but we might summarize the basic difference this way: Deep down in the United States, the rights of the individual (and his or her responsibilities) are paramount, and government comes second. In Europe, deep down, government comes first and the individual second. As Lester Thurow recently observed in Head to Head when he compared the prospects of Germany with those of the United States: the fundamental difference is between the communitarian German economy and the individualistic American economy.11 It is logical to expect such basic differences to be reflected in the medical technology structures of public macromanagement and private micromanagement that we described above. Attempts, therefore, to bring about fundamental convergence of these approaches would probably founder on historical and political rocks. Nevertheless, both conglomerates of states, in our opinion, could cross-fertilize each other much more productively in the field of technological innovation and diffusion in medicine.

REFERENCES

1. Wennberg, J.E. 1992. Innovation and the policies of limits in a changing health care economy . Pp. 9–33 in A.C. Gelijns (ed.). Technology and Health Care in an Era of Limits. Volume III. Medical Innovation at the Crossroads>. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

2. Reinhardt, U. 1989. Respondent: What can Americans learn from Europeans? Health Care Financing Review, Annual Supplement:97–104.

3. European Coordination Committee on the Radiological and Electromedical Industries (COCIR). 1991. Brussels: COCIR.

4. Goodman, C. 1992. The Role of Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty in Coronary Revascularization: Evidence, Assessment, and Policy. Stockholm: SBU.

5. Burstall, M.L. 1991. European policies influencing pharmaceutical innovation. Pp. 123–140 in A.C. Gelijns and E.A. Halm (eds.). The Changing Economics of Medical Technology. Volume II. Medical Innovation at the Crossroads. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

6. Hutton, J. 1991. Medical device innovation and public policy in the European Economic Community. Pp. 141–154 in A.C. Gelijns and E.A. Halm (eds.). The Changing Economics of Medical Technology. Volume II. Medical Innovation at the Crossroads. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

7. Bos, M.A. 1991. The diffusion of heart and liver transplantation across Europe. In B.A. Stocking (ed.). A Study of the Diffusion of Medical Technology in Europe. London: King's Fund Centre for Health Services Development.

8. Vos, R. 1989. Drugs Looking for Diseases. Groningen, The Netherlands: C. Rogenboog.

9. Griner, P.F. 1992. New technology adoption in the hospital. In A.C. Gelijns (ed.). Technology and Health Care in an Era of Limits. Volume III. Medical Innovation at the Crossroads. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

10. Williams, A. 1992. Priority setting in a needs-based system. In A.C. Gelijns (ed.). Technology and Health Care in an Era of Limits. Volume III. Medical Innovation at the Crossroads. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

11. Thurow, L. 1992. Head to Head: The Coming Economic Battle Among Japan, Europe and America. New York: William Morrow & Co.

DISCUSSION

IGLEHART: We have time for questions or comments for Dr. Gelijns and Professor Blanpain.

QUESTION: What is the impact of private insurance markets in European countries?

BLANPAIN: There is a two-pronged movement going on. First, a number of the reformers at the national level are introducing, if they did not already exist, complementary private insurance on top of the basic entitlement. The French have had a long tradition of permitting physicians to bill extra for some services. This was covered by special insurance. Cost sharing expenditures also is covered by private insurance. There is a drive to increase that and to make it a compulsory private insurance, which is a contradiction in terms.

Second, the insurance market is being freed throughout Europe. This is already the case for life and fire insurance, for example. There is still discussion of whether that market will be free and whether, for instance, a private health insurance fund will move into another country. Yet, in my case, my own health insurance gives me access to Blue Cross and Blue Shield and Japanese health insurance; I have access to all of these private groups. So, yes, this thing is moving very rapidly, and the big companies are positioning themselves strategically. Blue Cross is already on the European continent. For example, one private fund from the United Kingdom has moved into Spain, Greece, and Hong Kong and is now in Red Square (Moscow).

GELIJNS: As you know, in The Netherlands there is enormous radical change going on in the health care system, in which they are basically changing from a private and public system of insurance to providing a basic health care package for the whole population, and then the population can privately insure themselves for other elements of care that are not provided in the basic package. The interesting question that is posed by such change is how to determine what will fit into the basic health insurance package. For instance, in The Netherlands, they have set up four criteria; the first and second criteria are effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, which are rather technical; but then there are two social criteria. One of them is what is society considers appropriate and the other is care that individuals can pay for themselves. Thus, one of the debates going on now in The Netherlands is whether to throw in vitro fertilization out of the basic insurance package because society would not consider that necessary care and whether to exclude homeopathic medicine and adult dental care on the assumption that individuals would be able to pay for that themselves.

BLANPAIN: We took the birth-control pill out of the package last week.

QUESTION: Some in the United States argue that we will not have medical reform without tort reform. To what extent does malpractice play a part in European reform movements?

BLANPAIN: It does not play the same role in Europe as it does in the United States. There is an upsurge in the number of liability cases being brought to court in Europe. The Swedes and Scandinavians have installed a no-fault system, whereby things are settled administratively and few cases go to court. There are those who predict that we may end up in an American situation because liability premiums are going up, but still, it is not comparable. My wife pays $77 a year for liability insurance.

QUESTION: In the United States we are seeking some relationship between the way we finance health care and our capacity to control costs.

Granted, there are many differences between Europe and the United States in terms of culture, of the relationship of people to government, and so forth. But are there any lessons to be learned in regard to the ways in which particular governments or portions of countries have attempted to control the rate of growth of health care costs when a specific intervention has been clearly shown to affect such costs in a predictable way independent of all these other variables? Can we learn something from even portions of these systems that might be relevant?

BLANPAIN: That is a good but very complicated question. There has been kind of a merry-go-round of identifying various culprits thought to be responsible for the cost escalation. The hospitals came first; they were the ones that were responsible. That has led to measures to stop further hospital expansion and to reduce the number of hospital beds, which took a long time. The British never started building new hospitals, and their health service rationalizes that it needs only three beds per 1,000 population. In Belgium we were building hospitals. So that was the first thing, control hospital supply. Then it was realized that the physicians were the major determinants of health care expenditures and service utilization. And so the question was how to control the numbers of physicians, because the more physicians you have the more utilization there will be. Most countries moved to control medical school enrollment, with the exception of Belgium. That is why we have so many unemployed physicians. Then came technology. Technology became the culprit, and most countries, with very little study, began rationing the use of certain technologies. If there was a king—and some countries still had a king—then it was up to the king to decide whether you could have a machine. The Belgian king went so far as to issue a zero lithotripter norm, which meant that no one could have one. All of these forces have been at play. Together with strict price controls, pharmaceutical industries also are now being taxed on their marketing portfolio. If they have a marketing effort of $100 million, they had to pay a $20 million tax to the government. That was raised to $30 million last week. It is not always logical, but it works.

SHINE: You just told us that all of these systems are in some form of crisis in terms of their cost problems.

BLANPAIN: Yes, but the crisis now is basically that it is not a crisis of cost containment. It is a crisis of coping with what they want beyond cost containment. It is a crisis of ongoing inefficiency and of quality and inequality. We could be doing more than we are; that is what is driving reforms now. It is no longer a question of keeping costs in line with growth. Most countries do that. They are already beyond that problem.

GELIJNS: Through their macromanagement, European countries have basically installed very strong institutional and decision-making

frameworks that force choices among technologies and lead to a more orderly introduction of technology, although they also have problems in terms of delays, waiting lists, and so on. The biggest problem is that the countries have a very weak analytical capability to make decisions. Vice versa, you could say that the United States has a very strong analytical capability but does not have a very strong institutional or decision-making framework that forces choices among technologies within its health care systems. That will be an important learning point.

BLANPAIN: It is fair to say that in many cases in Europe, the analytical activity is a justification of a decision already made.

QUESTION: Dr. Blanpain said that there were possibly 1,400 physicians who were on unemployment insurance. Is this something that is happening in other European countries as well, and if so, what is the impact on the medical schools and/or federal policies and interventions?

BLANPAIN: Yes, it is happening in many European countries, and to some extent it is also happening in The Netherlands and France; unemployment is serious in Spain, and it is out of control in Italy. Even if a country has stringent policies for controlling entry into medical school, EC regulations allow students free access to other schools. Belgium does not block access to medical schools by its own nationals, so it cannot block access by other EC nationals. Among the first-year students at Leuven University are some 200 Belgians and 500 Dutch. Thus there is a serious problem. The Belgian government tried to stop that by making non-Belgian students pay the full cost, but that was overruled by the Court of Justice. The Court ruled that if your own students do not have to pay the full cost, no other national does. This is already perverting the practice of medicine. We now have all kinds of weird practices and therapies being marketed. My wife is bombarded with courses in all kinds of alternative modes of therapy, and they try to get them covered by the health insurance system. The United Kingdom has had the best control of their health professions workforce.

QUESTION: There is a philosophical word that appears in European health policy discussions that is almost never used in American health policy discussions. What does “solidarity” mean?

BLANPAIN: “Solidarity” goes back to the Middle Ages, when in small guilds or workshops people would contribute to a small fund that could be used if there was a case of sickness. Out of that grew the first health insurance program in Germany under Count Otto von Bismarck. Everyone could contribute to a sick fund that probably would be used for someone else. The principle of solidarity is still very, very high. So there is no premium on the basis of your illness but on the basis of the fact you are just a member of the solidarity group. Now people are increasingly

protesting and saying, “Wait a minute, why do I have to pay for this lung cancer? He should have stopped smoking.” In Norway, for example, if you were a smoker and you needed bypass surgery, you went to the bottom of the waiting list because you were a smoker. It is not fair and it is not just, but I think the procedure has now stopped. So the concept of solidarity is being reassessed. If people neglect their own health, are they entitled to receive care? If people do not wear safety belts, should they be covered fully?

QUESTION: One of the issues of discussion in the past was how much actual rationing of care there was in Europe, and if there is rationing now, where is it carried out? What financial impact does it have?

BLANPAIN: I would like to more carefully define the meaning of rationing. I do not see rationing in the sense that Webster's Dictionary does, which is as an equitable distribution of resources. What I do mean is that someone is denied access to care on demand, and must wait. Part of patient dissatisfaction and the request for reform relates to having to wait for care. Three years ago in the United Kingdom, a Labour parliamentarian was attacked by the Conservatives in parliament. They wanted to know why he had gone to a private hospital for his glaucoma and for his cataract operation? He hesitated and then said, “well, I'm 72, if I have to wait another 3 years that is my life. ” There is a lot of rationing, and there is even a lot of it on the continent, but not so much as in Scandinavia and the United Kingdom. Why is there so much rationing in Scandinavia and the United Kingdom? I personally believe that it is a cultural phenomenon.

QUESTION: One of the transformations that is going on in the United States is the movement from inpatient acute care to outpatient care and the creative use of the ambulatory environment. That is literally a result of the changes in the method of reimbursement by the government. Is that happening in Europe as well, and is it solely attributable to cost pressures?

BLANPAIN: I think it has three sources. It is cost containment because hospitals cost more than the alternatives. But it is also because of a reduction in hospital supply. There are not enough beds for more patients. It is also a result of technology. Limited invasive technology is allowing us to do things on an ambulatory basis or in another setting. These three forces are working together. But it is big business in Europe today.

QUESTION: So it is in some way a response to what has been happening in the United States?

BLANPAIN: Yes.

GELIJNS: In the United States, as you said, the reimbursement system drives people and their behavior to get out of the more strictly controlled setting of the hospital. That does not happen in Europe as much, and I think that there is less movement to ambulatory care, freestanding surgical units, diagnostic centers, and home care than you see in this country.

BLANPAIN: I think we will catch up in just a couple of years.