Response to Jo Ivey Boufford

Alan R. Nelson

Dr. Boufford has elegantly described the role and “culture” of primary care training and delivery in the British National Health Service. I have been asked to comment on primary care in the United States in the context of changes that appear to be on the horizon, what needs to be done to ensure that Americans have the right kind and amount of primary care services available to them, and the roles and responsibilities of the private sector and government in setting and achieving sensible goals in the mix of the medical work force.

We should begin by agreeing on some definitions. Primary care is a term that means different things to different people. Dr. Philip Lee has called primary care “an idea in search of a paradigm.”1 The Institute of Medicine (IOM) in a 1978 reportils 2 concluded that “primary care is distinguished from other levels of personal health services by the scope, character, and integration of the services provided.” The IOM study described five attributes that are essential to the practice of primary care: accessibility, comprehensiveness, coordination, continuity of services, and accountability. I will use for the purposes of my discussion the definition developed by the Council on Graduate Medical Education (COGME) in its report issued in October 1992. According to COGME, primary medical care is characterized by the following elements:

-

First-contact care for persons with undifferentiated health concerns.

-

Person-centered, comprehensive care that is not organ or problem specific.

-

An orientation toward the longitudinal care of the patient.

-

Responsibility for coordination of other health services that relate to the patient's care.

Physicians who provide primary medical care are trained as generalists. Their training, practice, and continuing education involve the following competencies:

-

Health promotion and disease prevention.

-

Assessment/evaluation of common symptoms and physical signs.

-

Management of common acute and chronic medical conditions.

-

Identification and appropriate referral for other needed health care services.

When the elements and competencies of primary care are defined clearly, the physician specialties that constitute the primary care specialties become evident—those trained, certified, and practicing in the specialties of family practice, general internal medicine, and general pediatrics. 3

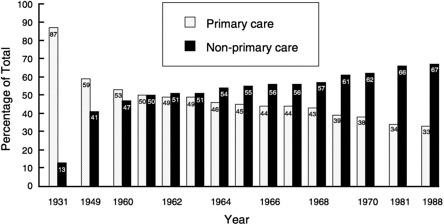

As Dr. Boufford stated, the United States has a comparatively small proportion of physicians practicing in primary care specialties. Other industrialized countries have 50 to 75 percent of their physicians practicing in primary care, whereas in the United States the proportion of non-primary-care specialists is about 67 percent (Figure 1).

The United States has about 20 practicing physicians per 10,000 Americans (a ratio somewhere below the median for developed coun-

FIGURE 1 Decrease in primary-care M.D.s as compared with other specialties.

tries). However, only one-third of physicians are in primary care specialties, divided among general internal medicine with 13.9 percent, family practice with 12.9 percent, and general pediatrics with 6.7 percent.3

Policymakers have targeted this disparity as data have become available suggesting that specialists in technologically intense fields contribute to an overuse of high-tech and high-cost procedures and services —apparently confirming the old suspicion that if one's only tool is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

Of even greater concern are the trends that show that the mal-proportion of primary care specialists is worsening. The worry is compounded by the fact that it takes a decade before any measures to influence students' career choices have an impact on the market because of the length of the training periods involved.

Data from studies of medical school seniors' specialty preferences conducted by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) show that the proportion favoring primary care dropped from 36 percent to 14 percent in the last 10 years, and the decline was spread across the board, from 50 to 77 percent.4

If that was not bad enough, the number of slots in internal medicine programs that are for transients, the preliminary positions, increased by 133 percent.5 These positions were filled by graduates who intended to stop off in internal medicine for a year or two while they waited to be accepted into anesthesiology, emergency medicine, or another program that better suited their expectations as a career choice.

What are these expectations? Some are related to a more controllable life-style such as regular hours. Some are linked to the explosion of knowledge and the desire of many to master a smaller subset of the field rather than struggle to maintain competence across a broader range. Some expectations are fueled by positive role models encountered during a student's clinical years. But students today also understand economic realities.

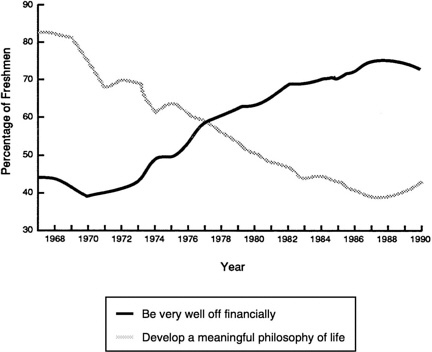

In a 25-year longitudinal survey of college freshmen cited by Colwill in his New England Journal of Medicine article,6 Astin documented a profound change in the responses to two questions that may serve as proxy indicators of changing values among students. 7

The proportion of freshmen who felt that a meaningful philosophy of life was very important dropped from 82 percent in 1966 to 40 percent in 1986. Conversely, the proportion of students who thought being financially well off was very important nearly doubled, from about 40 percent to almost 80 percent (Figure 2). During this period, interest in business as a career increased markedly and interest in education declined. According to Colwill, many who work with medical students believe that their attitudes mirror those of society in general.6

FIGURE 2 Motivational factors for college freshman in making career selections.

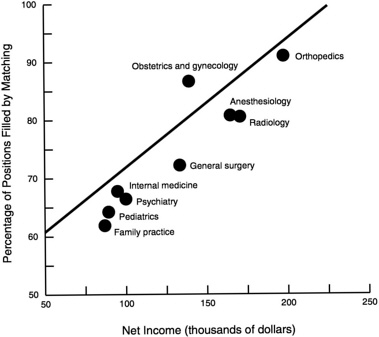

The matching of graduating students and available residency slots reflects the desirability of the field of practice. Colwill cites a study of the correlation between income derived from practicing a particular specialty and the percentage of available residency positions filled by matching. A straight-line correlation is striking (Figure 3).

As a final note, although only 55 percent of physicians in traditional internal medicine training programs were filled with U.S. medical graduates in 1992, the number of international medical graduates in those programs increased dramatically, to 1,400 from 1,007. And, not necessarily related, the number of Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Fraternity members selecting primary care has declined, supporting arguments that the quality of students selecting primary care may also be declining.

To summarize the major factors responsible for the decline in the attractiveness of primary care as a career choice for students, the AAMC Task Force on the Generalists Physician cites “the increasing ability of non-generalist practitioners to diagnose and treat many heretofore untreatable conditions, the inherent appeal of the astonishing technological

FIGURE 3 Desirable fields of practice.

advances that have occurred in several specialized areas, the desire to gain mastery over a well defined and circumscribed field, the prospects for greater financial rewards, and the perception that many of the non-generalist fields permit greater control over one 's professional life, thus allowing adequate time for one's family and other interests.”8

The academic community should accept blame for a bigger piece of the problem than they reflect in their statement.

They have not adequately provided opportunities for students and residents to experience the real world of primary care practice by including mentorships in which trainees can see firsthand the rewards of longitudinal relationships with patients who also become friends. Neither have they uniformly provided residency training that teaches the necessary skills for confident and fulfilling primary care practice. Relegation of primary care to a triage role diminishes its attractiveness to any bright, motivated, modern young man or woman.

I would like to quote a letter from a young woman internist, Dr. Carol L. Bowman, from Joppatowne, Maryland. It was published in the January issue of the American Society of Internal Medicine's (ASIM) publication The Internist: Health Policy and Practice:9

I have been a practicing internist for two weeks. In my office I have an internal medicine text and an ambulatory care text that I madly read as the unsuspecting patients sit in my exam room.

Why don't I know how to treat sinusitis?

Why didn't I know that there are actually algorithms to follow to work up hematuria, abnormal liver function tests and proteinuria?

The problem is not that internists make less money or have less prestige. The problem is the training programs.

We needed exposure to internists who are practicing quality internal medicine with compliant patients in the community. We need to know that patients are not the enemy—that they can actually be quite nice when you have a few moments to spend with them.

Above all, we need to be trained. The internal medicine “training” has prepared me for acute myocardial infarction, congestive failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pneumonia. We still need to know WHAT TO DO! We need to learn how to be internists and to feel the thrill of learning and mastering a subject, just as other specialties do.

People involved in internal medicine training programs have to be responsible for exposing students and house staff to the mastery and joys of internal medicine.

I have been describing the reasons for the declining interest in primary care because there are no simple solutions for the problem. We must avoid reductionist thinking. Simply mandating a certain proportion of primary care specialists is not going to solve the problem. The American people do not like mandates, and at this point, we still value highly the right to choose a career and the place where we live. I firmly believe that we must understand the problem so that we can provide workable and practical incentives to overcome it.

The supply of primary care services is determined not only by the inflow of new practitioners but also by the expansion and contraction of the existing pool and by the rate at which providers of care leave the pool.

The U.S. system has unique features that expand the capacity of the system to provide primary care beyond the number of primary care specialists. The most important feature is the fact, desirable in my view, that medical subspecialists provide a lot of primary care —much of it high-quality and cost-efficient care.

I know of no data on the percentage of primary care provided by medical subspecialists, but a few years ago, an ASIM survey showed that 75 percent of internist subspecialists also did some primary care. As an endocrinologist, I would certainly provide routine primary care services for my diabetic patients. (To send them to a gynecologist only for a Pap smear, for instance, would be inconvenient for them and wasteful. When a thyroid patient called to see me because she discovered a breast lump and her primary care physician's first opening was in 6 weeks, I exam-

ined her that day, doing whatever follow-up care was necessary. I was an internist first and an endocrinologist second.

The future availability of primary care services is also influenced by an increasing supply of women physicians and employed physicians. Data from the American Medical Association show that women work fewer hours per week and fewer weeks per year than their male counterparts. Finally, as more physicians take salaried positions, the productivity of each physician probably will decrease because salaried physicians see fewer patients, on average, than their self-employed colleagues.

Projections of physician supply must also take into account the exit of physicians from the work force. Very little is known about burnout and its contribution to early retirement or to a decision to change specialties. From all that I hear, I have strong suspicions that burnout is increasing in importance, being fanned by hassles, professional liability fears, decreasing income, and the desire for a less demanding professional life.

Let me conclude with what we do not want to happen, what we do want to happen and some measures that we can take that will help to ensure that we end up with what we want rather than what we do not.

First, we do not we want to lose a unique and valuable component of the U.S. health care system: continuity of care by the same primary care physician across a range of settings. Our system, which permits a primary care physician to provide much of the hospital care that a patient requires, is superior because it allows for the coordination of the care provided by additional consultants or surgical specialists in the out-patient or long-term-care setting as well. My patients expect me to run things for them in the hospital because “I know them” and I am “their doctor,” even though an invasive cardiologist might do their angioplasty or a surgeon might take out their gallbladder. The adequacy of information transfer across different care settings is much better in this country than in the examples in the United Kingdom that I have seen. Further, I believe that my patients are willing to pay more to have me around, even though another consultant is participating in their care.

Second, we do not want to have primary care as a career relegated to a “last-resort” role by a public policy that calls for any kind of body in the slot. That is why I feel so strongly about providing the right kind of incentives to get the right kind of people into primary care and to keep them there.

Third, we do not want to embrace central planning with insensitive feedback. Experience with government's involvement in manpower (to use the old terminology) in the past is not particularly reassuring. Neither was our experience with the Health Planning Act. I agree with the legitimate role of government in setting goals and providing incentives, but I am not convinced that government can enforce quotas, and I have

grave concerns about proposals to control distribution by central edict. The rest of the world, after all, is moving away from central planning and toward free markets.

What we do want to happen is this: We should seek to achieve curriculum reform to make training relevant to our patients' needs, including a large dose of humanism as part of the training and mentorships of the right kind at the right time. Faculty should be properly rewarded to ensure high-quality role models.

A 50 percent goal for primary care as a percentage of the total physician population seems reasonable, but it will take time to achieve this goal even under the best of circumstances.

We should identify and seek to correct the factors causing premature departure from primary care practice. Losing an experienced and qualified physician because of burnout is wasteful and sad.

We should provide undergraduate financial incentives, including loans and scholarship programs, to train more generalists and fewer non-primary-care specialists and subspecialists.

We should provide higher stipends for primary care residencies compared with those for other residencies to lessen the education debt burden and provide loan forgiveness for those who practice in areas with a shortage of primary care physicians, even though the record of retention is spotty.

The most important changes must come in the practice environment. The economic incentives to enter generalists' fields must be increased, and the incentives to enter specialties must be reduced. We can do this by extending the resource-based relative value system to all payers and by speeding up the transition to full implementation of the Medicare payment reform process. Medicare's geographic cost adjustments must be based on actual costs, and a single volume performance standard and conversion factor should apply to all specialties. The most important way to enhance the attractiveness of primary care is to value it and pay for it properly.

The environment in which primary care is practiced must be more friendly, less hassled, without the billing headaches that come from the multiple-patient-contact environment, and without conflicting and uncertain Medicare carrier policies. Payment denials for concurrent care, provided at some sacrifice in an effort to fulfill an unwritten obligation to a loyal patient, drive physicians crazy. Mentorships are not going to work if the mentor is complaining all of the time, and many of them have a lot to complain about, with the need to cope with a flood of regulations accompanying, for example, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the American with Disabilities Act, and limiting charge exception reports.

A single-payer system would not be simpler. Our experience with Medicare tells us that government cannot do it simply.

We are entering what George Lundberg has called the Golden Age of Medicine, and it is a message that we must continue to send as we go through the fundamental reorganization of the way in which health care is financed and delivered in this country. George quotes Dizzy Dean, who, when the bases were loaded and nobody was out, used to say, “The ducks is on the pond.” He believes the bases are loaded with resources and opportunities. If we manage our resources properly, we will be successful. Will we be able to achieve a goal of adequate numbers of well-trained and competent primary care practitioners? I am as optimistic as that other great American philosopher, Yogi Berra, who said, “They said it couldn't be done, but sometimes it don't always work out.”

REFERENCES

1. Lee, P.R. 1992. Address at the National Primary Care Conference, Washington, DC, March 29.

2. Institute of Medicine. 1978. A Manpower Policy for Primary Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

3. Council on Graduate Medical Education. Third Report. Improving Access to Health Care Through Physician Workforce Reform: Directions for the 21st Century. October 1992. Washington, DC: Council on Graduate Medical Education.

4. Petersdorf, R.G. 1992. Report to the Federated Council for Internal Medicine. October 29. Washington, DC: Federated Council for Internal Medicine.

5. Altus, P., et al. 1992. Declining interest in internal medicine. Archives of Internal Medicine 152:1374–1375.

6. Colwill, J.M. 1992. Where have all the primary care applicants gone? New England Journal of Medicine 326:387–393.

7. Astin, A.W. 1991. The American freshman: 25 year trend. Los Angeles: University of California.

8. Association of American Medical Colleges. 1992. Task Force on the Generalist Physician. October 8. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges.

9. Bowman, C.L. 1993. Inadequate training. The Internist: Health Policy in Practice, January:28.

DISCUSSION

IGLEHART: Now it is the audience's turn to ask the panelists questions and to comment on the presentations.

SHINE: Dr. Boufford, you described the “fundholding” approach as being used in terms of the general practitioners in Britain. You said they buy hospital services. Does that mean that the primary care provider must become part of a group? Can an individual practice individually? How would they buy hospital services? The flip side of that is a question for Dr. Nelson, namely, if you are a terrific patient advocate and the pri-

mary care provider, why not capitate you in the same way that the British are talking about for their general practitioners?

BOUFFORD: The fundholding system is open to any GP practice with a list of over 11,000 (generally a two- to three-person practice). They tend to be the larger practices. While the traditional GP has the ability to buy laboratory and radiology diagnostic services from the hospitals and limited specialty outpatient consultants, fundholders now buy all elective services, including day surgery and elective medical and surgical work, both outpatient and inpatient. In some areas, they hold a very large segment of the district's money. The policy dilemma is that they are free to negotiate with the hospitals in their area for the prices and the consultants that they want, the data exchange that they want, and the timeliness of the visit. They are called “wild cards” in the reform because they are doing their own thing outside of the district structure. In some parts of the country, the GP fundholders hold as much as 40 percent of the district's budget for services in the aggregate. Yet, unlike the district, the GP fundholders have no responsibility for the health of the population. The district is essentially losing a percentage of its flexible money which is going into the pockets of the GP fundholders, who only need to concern themselves with the medical care of those from their list who seek services. That is a policy tension that will probably get worked out by putting some kind of responsibility on the community health dimension.

SHINE: It sounds like a macro health net organization.

BOUFFORD: The individual fundholders apply to the region and the Secretary of State for Health to be designated. But it is not a net. There are examples yet of GP fundholders developing consortia, but it is inevitable. That would be the logical first step toward a real managed care template.

NELSON: I have no argument at all with capitated systems. As a matter of fact, I think that the best system is a pluralistic system with the right to choose. I was careful in practice to not let my clinical judgments be overly affected by my risk pool. As a matter of fact, I had some concerns because my ophthalmologic colleagues were telling me that they were not receiving appropriate referrals for diabetic retinopathy, for instance, because the primary care practitioners at that time were at risk in a capitated system. But I had a simple way of dealing with that as a practitioner: I just never opened the periodic information that was provided on how I was doing with my risk pool. I told the business manager at the end of the year that if I owed them a lot of money to pay it. But I practiced lean medicine, and I did not want to have my clinical judgment adversely influenced.

SHINE: This is the blind trust approach.

NELSON: Anyone who is tracking trends understands that capitated

systems and managed competition are likely to be very important. On the other hand, I am struggling to find out how small groups of internists or solo internists in rural settings are going to fit into that new network. Enthoven and Kronick and others have not explained that well enough to me yet.

QUESTION: Would both of you comment on the roles of nurse practitioners, physician 's assistants, and nurse midwives in England and under health care reform in the United States? And then, finally, Dr. Nelson, if you could comment on retooling subspecialist internists into primary care physicians if the incentives were right.

BOUFFORD: There is an historical network of nurses—community health nurses, home visitors, and nurses for chronic care and some specialties like cancer—that are now increasingly managed through community health service trusts. The trusts are run as organizations that sell their services to GPs and to acute care hospitals that provide home care. There are a variety of allied health professionals, and occupational and physical therapists in those community trusts, along with optometrists, podiatrists, and dentists. The nurse practitioner role is developing slowly. The notion of nurse practitioners and physician's assistants has not been embraced very actively. A lot of the GP practices tend to develop “practice nurses” who perform many of the functions that you and I would recognize as being the roles of nurse practitioners. There is not an official job description yet. This has created a tension in the nursing profession, not surprisingly, in that these jobs are growing up within general practice, not within nursing, and there are questions about what their role should be and what kind of certification they should have.

QUESTION: Midwives?

BOUFFORD: Midwives are very active, but not as much as I suspected, interestingly. A major Parliamentary Select Committee report recently came out in favor of the use of midwives for routine maternity care, saying that the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists was being overly restrictive in its policies toward midwives. This caused a major flap that resulted in the resignation of one of the vice presidents of the Royal College because the college refused to adopt the findings of the report. So there is tension in the air.

NELSON: The trend toward the use of nurse practitioner services will likely increase. As a matter of fact, I think that the baby boomers' values are going to be reflected in a whole host of additional nontraditional care provisions, some of them scientifically based and perfectly valid, such as nurses as primary care providers, and some of them off the wall. Because I think that society is going to go through a decade of wanting to pick its own poison, to make its own choices and to reject

paternalism, the notion that “doctor knows best” is not going to sell. One of the ramifications may be that as each new cohort of care providers market their services, costs may increase because additional layers of services, not available in the past, would be provided. That is obviously speculation.

As far as retooling is concerned, I do not know that it is possible to retool. I thought that the trends for gastroenterologists would be for them to do more noninvasive procedures. I thought that cardiologists would decide that they had better learn how to treat tennis elbow so they could take care of a patient who came in with a pain in the arm and is afraid that it is a coronary. When found out that it is tennis elbow, instead of sending him or her halfway across town for a $75 shot from an orthopedist, the cardiologist could simply treat the tendonitis and take care of the problem. But I do not see that happening. That is why I tried to make a case for some fundamental restructuring of the medical curriculum so that at least even subspecialists who are relatively restricted in their scope of usual activities can provide enough of a range of patient care so that patients are not forced into a peripatetic bouncing from one part of the city to another.

QUESTION: I am a nurse practitioner. I have been a primary care specialist since 1965. Currently, there are about 30,000 nurse practitioners. There are almost 600,000 registered nurses. As nurse practitioners coming out of a baccalaureate program, we complain about costs. I guess the policy question is not how to shove and push doctors into primary care but whether it is cost-effective.

NELSON: I hope that I made it clear that I respect nursing practice as a valid and scientifically based discipline.

QUESTION: Something Dr. Boufford did not touch on that I would like to put on the table—because I think it is part of the future of health professional reform—is the matter of Medicare's very substantial investment in health specialist training, which is, I think, the sleeping giant of the health professions' or medical education's dilemma. The Bureau of Health Professions, which is the custodian of those great programs of the 1970s designed to fund primary care, provides about $150 million in programs supporting primary medical care education. In 1992, the Health Care Financing Administration spent $5.2 billion for direct and indirect general medical education (GME) subsidies to acute care hospitals for GME activities. The larger figure actually is the indirect subsidy, which is $3.6 billion. The direct subsidy is about $1.6 billion. Spokespeople for the hospital sector rise up in anger when one raises the issue of the indirect payments. They feel, with some historical accuracy but by no means clarity, that those funds are provided by Congress to offset other kinds of

payments, intensity of care, etc. Nonetheless, those funds are delivered to a hospital on the basis of the number of residents that it has trained, and a hospital can increase its take by increasing its number of residents on both the direct and indirect sides. If you take that $5.2 billion and divide it by everybody in training, every house officer in the country, and all the fellows—over 80,000—it comes out to about $70,000 per house officer. And if you are a house officer and never set hands on an adult patient, let alone a Medicare recipient, hospitals are still reimbursed for direct and indirect costs on average—and I say average, because it varies from hospital to hospital—$70,000 per year per house officer. That is a very substantial amount of money and it has been managed totally by policy, and the best-case policy is neutral from a primary care perspective. If one is working in a budget-neutral environment, which I certainly believe we are, there are funds in the system that could be used in a variety of ways to move residents toward primary care. This will require a crosswalk between the traditional focus of medical education in the Public Health Service and HCFA and the committee on Capitol Hill that controls them. It will require the creation of a new relationship.

BOUFFORD: As I mentioned, New York State is addressing this issue by taking a segment from the indirect pool in New York State and redirecting it to up-weight the reimbursement for primary care residents. I think the plan for next year is to stop allowing hospitals to claim the costs of fellows over a 3-year period and use that money to reinvest in the hospital, and, further, to increase the weighting to 1.5 for primary care physicians and give weights of 1.0 for internists and 0.9 for other specialty residents.

NELSON: I will take it even one step further. If there are set goals, such as those of the Council on Graduate Medical Education, and if those goals become fairly firmly accepted, whatever contribution government makes to medical education, including the research budget, can be utilized for leverage if that is what it takes.

QUESTION: As a fourth-year medical student, I have just recently become aware of these discussions on primary care. I am rather surprised to see that very similar discussions had been going on in the 1970s and the 1980s—and they are still going on. What is different now? Are citizens beginning to feel the crunch in their pocketbooks or is it because of Senator Harris Wofford's election campaign? What is different, and can we expect real change?

BOUFFORD: It feels like it did in 1979, but maybe it is better.

NELSON: One thing that is different is that studies are showing that high technology costs more and we are budget driven for good reasons. Another is that people do not like fragmented care; they want somebody

in charge in this country. I think that they are being forced to confront a situation in which they get shuttled from subspecialist to subspecialist without having the confidence of continuity and somebody being in charge. That is being reflected in the attitudes that are governing some of these changes.

QUESTION: As dean of a medical school I often hear students say the reason that they go into non-primary care specialties is because of the enormous debts that they have to pay back. If this is the case, why do we not do more of what we did in the past with the National Health Service Corps funding? Is that a way to help reshift this ratio of primary care physicians?

NELSON: It certainly should be public policy to continue to try that, but I do not know whether it will work by itself.

BOUFFORD: It certainly should work, and many states are taking that initiative. One of the conflicts, it seems to me, about the National Health Service Corps—maybe it is less true now—was people using it as a loan forgiveness mechanism rather than because they were really interested in primary care; as a result, their willingness to stay in practice after their commitment was over was often quite limited. There needs to be balance in terms of having enough other loan forgiveness programs, payback service programs, or other mechanisms so that the National Health Service Corps does not become the only route to paying medical school debts.

QUESTION: Dr. Nelson, it is hard to share your optimism given your figures. In 1980, 40 percent of the medical students were looking for primary care residencies; in 1991, that figure was 14.6 percent and everything seems to be going away from primary care. On the other hand, you argued against a central plan. I hope that means that you are not for a personnel policy in this country. We put $5.2 billion of Medicare money into the universities, and we put in a lot of money from the National Institutes of Health into universities. It seems to me that we ought to have some accountability in terms of what is produced, if we should have national health reform in this country. It does not appear as if we can really give access to every individual—and that means people in the innercity and in isolated rural communities —if we do not have an adequate number of primary care physicians. We are not going to reach that goal unless we have a national health policy.

And Dr. Boufford, could you comment on medical students? I had the opportunity of going to the University of Toronto and McMaster University, and as you know, Canada has reversed that specialist trend of the 1950s and 1960s and now has a pretty even mix of specialists and generalists; but the students seem to be very enthusiastic about primary care, and

it is not, as it is in this country, a profession that is looked down upon by the medical establishment. Unfortunately, I think the prejudice of medical schools against primary care is pretty strong. That, in my estimation, is one of the reasons why we do not have as many people going into primary care.

NELSON: I certainly do not resist or oppose the concept of a national medical work force policy. I think it is high time we had one. I expressed some concerns about constructing one in which primary care would get only second-class citizens because the incentives were not there or one in which you could force somebody to go to a particular area until their spouse said that he or she did not want to live there anymore. I rode once with a family practitioner in South Africa, and he had worked up in Kruger Park. He said that it was wonderful, that he took care of hippopotamus bites and lion attacks. He was there for 7 years. He then moved to a nice resort area. He said that he loved it and would have been there forever, but when his wife promised to follow him to the ends of the earth, she did not say for forever.

BOUFFORD: An important issue in the United Kingdom is the historical differentiation and clarity about the referral system; there is a real interdependence between specialists and GPs, and both are needed to make the system work. That is very powerful in terms of mutual respect and colleagueship. Personnel planning that limits the number of consulting posts means that a number of medical students go toward general practice because they know the waiting time to get a consultant post in another specialty is quite long. But the 50 to 60 percent who enter general practice is not necessarily by default by any stretch of the imagination. There is a media image that people who advise the government are GPs and specialists; the Queen has a physician who is a generalist; these are very big messages that get sent out. All patients have a GP who is their first line of contact; they trust that GP, and that is probably more powerful than anything else.

SHINE: I have to make one editorial comment. I was in the medical education residency training business for a long time, and while I agree with the necessity of dealing with the future of health professions training to better address our nation's needs, please do not forget that these students are very smart. They know how to work the system, and they know where they want to go. So the issue is still what kind of life-style they are going to have and what the reward system is. One of the reasons that capitated systems in which the primary care providers or the capitated players may be important is that it places control, authority, prestige, and everything else in a way that rewards the primary care provider. That is a very important message. I would submit that you can do this. I am not arguing that one may not need to change residency education, but

again, the doctors and the students will figure out a way to get around that if they believe that the ultimate outcome should be something different, unless the rewards are there for the long term. We must not lose sight of the question of what is the ultimate standing of the primary care provider in the society. In this society, it is measured by either dollars or control, unfortunately. We have to be very clear on how we are going to accomplish change.