2

Choices or Constraints? Factors Affecting Patterns of Child Care Use Among Low-Income Families

THE ISSUE IN BRIEF

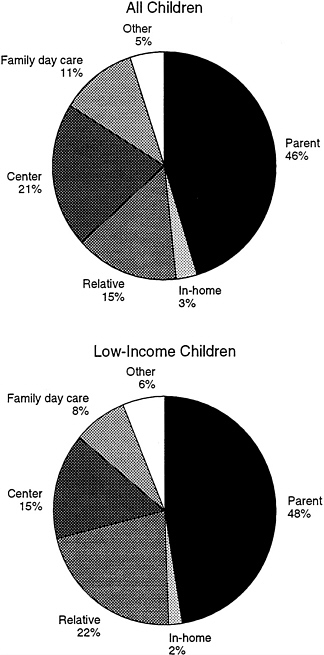

Low-income families tend to rely more on some types of child care and less on others, compared with families with greater financial resources. Specifically, they are more likely to rely on relatives and less likely to rely on center-based arrangements (Figure 1). Grandparents are an especially prominent source of child care for low-income, preschool-age children: 17 percent are cared for mainly by grandparents; 29 percent get some care from a grandparent. The child care arrangements of low-income families also vary greatly by household type and parental employment status (Table 1). Single employed mothers rely to a much greater extent on nonrelative arrangements (notably family day care homes and centers) than do other types of low-income families. In addition, among low-income families, about 24 percent of children under age 5 are in more than one supplemental arrangement on a regular basis (Brayfield et al., 1993). Reliance on multiple arrangements varies, however, from 14 percent of low-income preschoolers with two parents to 31 percent of those in single-mother families and 45 percent of those in employed, single-mother families.

Some argue that these disparate patterns reflect income-based preferences for different forms of care. Others contend that, although preferences may play a role, the child care choices of low-income families are seriously constrained by financial and other factors. Low-income families

FIGURE 1 Main child care arrangements of all children and low-income children under age 5.

Source: Adapted from Hofferth et al. (1991) and Brayfield et al. (1993). Reprinted with permission.

Note: Percentages total more than 100 due to rounding. Figures include children with employed and nonemployed parents.

TABLE 1 Main Child Care Arrangement of Low-Income Children, by Household Type for Children Under Age 5

SOURCE: Adapted from Brayfield et al., 1993. Reprinted with permission.

face much more limited child care options than higher-income families. Furthermore, prospects that low-income families' reliance on child care may effectively be mandated by federal and state welfare reform initiatives have raised concerns regarding parents' ability to place their children in care arrangements that they feel assured are safe, nurturing, and supportive of their children's growth and development while they strive to meet work requirements.

What is known about the child care preferences of low-income families? Do they define “good” child care differently from middle- and upper-income families? What influences impinge on the capacity of low-income families to match their preferences with their actual child care arrangements, and do they differ from those that affect other families? Is there evidence that the child care choices of low-income families are constrained? These questions were addressed by several of the presentations at the workshops.

SUMMARY OF RESEARCH PRESENTED

Patterns of Child Care Use

Low-income families resemble other families in the considerations that guide their child care preferences and choices. Like all families, they balance perceptions of what will benefit their children with the demands of their jobs, financial limits, and need for convenient arrangements. Their views of good child care are also similar to those of families with greater resources, emphasizing the need to protect their children's sense of security and well-being. At the same time, the translation of these considerations into preferences for various types of care appears to differ somewhat for low-income and other families.

The National Child Care Survey (a telephone survey of a nationally representative sample of households with a child under age 13), reported by April Brayfield,1 examined what low-income families with annual incomes below $15,000 are using for child care and why they are using it. Approximately 48 percent of low-income children under age 5 are cared for mainly by their parents; an additional 10 percent are cared for exclusively by their parents. Only 22 percent of children with two employed parents and 8 percent of children with a single employed mother are cared for solely by their parents (15 percent of children whose mothers are in education and training programs are exclusively in parental care).

Of those relying on nonparental care, the distribution of preschool-age children across types of care varies greatly by the household type and employment status of the mother. Care by a relative is especially prevalent for low-income preschoolers with single mothers (26 percent), employed mothers (28 percent), and mothers in education and training programs (23 percent). Children under age 5 in families headed by employed single mothers are also heavily reliant on family day care (21 percent) and center-based care (27 percent) (see Table 1).

The National Child Care Survey also asked parents why they chose their current child care arrangement and found discernible differences by family income. Families with incomes under $15,000 were most likely to state a preference for relatives as caregivers (35 percent), whereas families with higher incomes were most likely to cite quality of care as the pre-

|

1 |

Workshop participants are identified by their full names when they first appear in the text. For a complete listing of participants and affiliations, see the workshop agendas in the appendix. |

dominant concern (37 percent of the middle-income sample and 47 percent of the high-income sample cited quality, compared with 26 percent of the low-income sample). “Quality,” in turn, was most often defined as a feature of providers—whether they are warm and loving, their reliability, and their experience with children, features that many low-income families appear to equate with relative care rather than with the generic response choice of “quality.” Low-income families were also four times more likely to mention cost (affordability) as a factor that affected their child care choices than other families (16 percent versus 4 percent for high-income families).

Among a subsample of low-income families with children under age 5 who expressed a desire to change arrangements, however, 70 percent cited quality of care as the major reason. Indeed, poor quality was cited slightly more often by low-income parents seeking to change than by parents of all income levels who sought a change, 60 percent of whom mentioned quality concerns. By way of comparison, only 3 percent of low-income families mentioned burdensome child care fees as a reason for preferring alternative arrangements. It is possible, of course, that parents may prefer to tell interviewers that quality is more important than other factors, such as cost (see Hofferth and Wissoker, 1992). But there is now a substantial literature that replicates the findings of the National Child Care Survey regarding the salience of quality considerations.

|

“CONCERN FOR THE SAFETY OF CHILDREN IN THESE SETTINGS OFTEN TAKES PRECEDENCEOVER EVERYTHING ELSE.” Siegel and Loman, 1991 |

Looking across a range of studies, Mary Larner elaborated on these survey findings. Low-income parents, particularly those receiving public assistance, appear to place a premium on considerations of safety and trust, followed by a concern for nurturance and educational opportunities when searching for child care. These findings need to be placed in the context of the high-crime, inner-city areas in which many of these families are raising their children. They also raise issues of who is trusted to provide child care by families who have traditionally relied on relatives as their primary support system, and who are likely to have experienced prejudice in the broader society. It is not surprising that these considerations of

safety and trust lead some low-income families to prefer care by relatives; for others, center-based care, with its public visibility, is viewed as offering greater protection. Seldom preferred is care by unfamiliar adults in home settings, either for preschool or school-age children (Larner and Phillips, 1994; Mitchell et al., 1992).

In sum, the evidence presented at the workshop suggests that all parents report a primary concern with the well-being of their children when choosing and rearranging child care for their young children. Characteristics of the provider are viewed as the primary factor in seeking good child care. In addition, low-income families appear to place a special emphasis on basic issues of safety and trust in the provider. Concern with other aspects of quality may be a luxury to families whose neighborhoods are far from safe havens for childrearing and whose lives are highly precarious.

Levels of Satisfaction

Data on parents' satisfaction with child care provide an important link between their stated preferences and their patterns of use. If parents are largely satisfied with their arrangements, one might assume that they are successfully obtaining care that matches their choices. If they are dissatisfied and seeking to change providers, choice becomes a matter of their capacity to bring the care that they are using more in line with what they want. Some note, however, that it may be difficult for some parents to acknowledge to interviewers that they are dissatisfied with their child care, particularly if they believe that it may stigmatize them as “bad parents” and call attention to their own concerns about the well-being of their children.

Across studies, virtually all parents who use child care indicate that they are satisfied with their current child care arrangements. Even among low-income families, about 95 percent of those using care for children under age 5 say they are satisfied or highly satisfied (Brayfield et al., 1993). These summary data, however, camouflage the complex portrait of parental satisfaction that is now emerging from research.

According to the National Child Care Survey, low-income single mothers were substantially less likely to indicate high levels of satisfaction (67 percent) than were low-income two-parent families (84 percent). There was no significant difference in satisfaction between parents relying solely on themselves as caregivers and families using some supplemental care.

Respondents were also asked, “Assuming you could have any type or combination of care arrangements you wanted for your youngest child, would you prefer some other type or combination of types instead of what you have now?” Across all income groups, 26 percent indicated that they wanted to change arrangements. The figure for low-income families was 27 percent. The group most likely to desire a change was employed single mothers, 43 percent of whom indicated a preference for care that differed from what they were using. Preferences for alternative arrangements also varied with the current type of care. Families using centers were least likely to want to change; those using in-home providers were most likely to desire a change. Half of those seeking a change wanted to switch to child care centers, the form of care many prefer as their children grow older.

A number of smaller studies, reported at the workshop, have also attempted to assess whether low-income parents would like to change their child care arrangements. In Marcia Meyers's sample of 225 single mothers participating in California's welfare-to-work program (called GAIN), one of three mothers indicated that she would have preferred a child care arrangement different from the one she was currently using (Meyers, 1995). Gary Siegel and Anthony Loman's interviews with mothers receiving Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) in Illinois revealed that mismatches between care preferred and care used are especially prominent among those seeking center-based care. In that study, 44 percent of the parents who were using some form of child care indicated a preference for child care centers, yet only 19 percent were using them (Siegel and Loman, 1991). Alternatively, most of those who preferred care in their own home or a relative 's home were using this type of care. In a related finding, 65 percent of the respondents who had worked or gone to school in 1990 reported difficulties finding care that they were confident was safe, and a comparable share reported difficulties finding care “that is good for my child.” Other studies of low-income families have also reported that one-third or more of mothers express a desire to switch arrangements (Kisker and Silverberg, 1991; Sonenstein and Wolf, 1991).

In sum, low-income single mothers who are combining work and childrearing with neither the financial nor the social resources to facilitate access to suitable child care indicate substantially lower levels of satisfaction and stronger desires to change arrangements than do other mothers. Among low-income families, for example, two-parent dual-employed families are over twice as likely to rely primarily on the parents for child

care (and half as likely to use family day care and center care as their main arrangement) than are employed, single-parent families (Brayfield et al., 1993) (see Table 1 ). Families that rely on arrangements made informally with friends and relatives are also disproportionately likely to indicate that they wish they could change their arrangements.

Factors Affecting Patterns of Use

Low-income parents, like all parents, undoubtedly choose the child care that they most prefer given their current circumstances and limitations. It is reasonable, however, to ask whether these choices are best for the children and whether giving these families more resources for child care might help them chose a more preferred alternative that better meets their needs. The workshop participants inquired specifically about the degree to which the child care choices of low-income families are constrained.

Several lines of research presented at the workshop have attempted to discern whether there are constraints on families' use of child care, and whether these constraints disproportionately affect working low-income families. The evidence suggests that the answer is “yes ” to both questions, with work schedules and cost of services figuring prominently among the constraints on working low-income families ' ability to obtain the child care that best meets their needs and that they perceive as safe and beneficial for their children.

|

“ALL FAMILIES ARE CHALLENGED BY MANEUVERING IN THE CHILD CARE MARKET, BUTESPECIALLY LOW-INCOME FAMILIES. THE AFDCPOPULATION HAS TO MANEUVER BOTH THECHILD CARE AND THE LABOR MARKET.” Bobbie Weber (comments at the workshop) |

Structure of Low-Wage Work. The structure of low-wage work and its lack of fit with the structure of more formal child care options restricts the access of low-income families to child care centers and many family day care homes. Data from the National Child Care Survey indicate that one-third of working-poor mothers (incomes below poverty) and more than one-fourth of working-class mothers (incomes above poverty but below

$25,000) worked weekends (Hofferth, 1995). Yet only 10 percent of centers and 6 percent of family day care homes reported providing care on weekends. Almost half of working-poor parents worked on a rotating or changing schedule, further restricting these families ' child care options to more flexible arrangements made with relatives, friends, and neighbors. These features of low-wage work also appear to promote reliance on multiple providers as a way of patching together child care to cover parents' nonstandard and shifting work hours (Siegel and Loman, 1991). Meyers added that irregular and unpredictable work schedules led to disruptions in child care for the families in her study of the California GAIN program (Meyers, 1995).

Cost of Child Care. The cost of child care also constrains parents' choice of child care arrangements. In 1993, the average weekly expenditure on child care among those who paid something for that care was $54 for families with a monthly income less than $1,500 and $61 for those with monthly incomes from $1,500 to $2,999 (Bureau of the Census, 1995). These numbers camouflage the wide disparities in the proportion of family income that these groups spend on child care. The $54 paid weekly by very low-income families constitutes 24 percent of their household income, compared with the 6 percent of income that is spent per week on child care by families with monthly incomes of $4,500 or more.

These numbers are remarkably similar to those found in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care reflecting expenditures on care for 6-month-old infants (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 1995). Families earning under $1,250 per month paid, on average, $261 per month for child care, or 33 percent of their family income. Families earning over $3,750 per month paid $417 per month for care, or 6 percent of their income.

Because costs of care vary systematically by type of care, as does the likelihood that a provider will offer care free of charge, the range of financially viable options varies systematically with a family's disposable income. Across all families, in 1993, for example, approximately 90 percent of those using center-based and family day care arrangements paid for care; 17 percent of those using relative care paid for care (Bureau of the Census, 1995).

When AFDC recipients in Illinois were asked about practical constraints on their child care choices (Siegel and Loman, 1991), the cost of

care was the most frequently cited barrier and led many to rely on care by relatives. Over 80 percent of those who worked or were in school reported problems with the cost of care. Despite the strong preference for center care in this sample, few could afford the full cost of this form of care ($83 per week, or 78 percent of the average cash income of the families in the study).

Data from the National Child Care Survey confirm this local portrait: families in poverty with a child in a center-based program are highly likely to be receiving financial assistance (Hofferth, 1995). The survey data show that 9 out of 10 nonworking-poor families and almost half (42 percent) of working-poor families with a child in a center-based program reported receiving financial assistance.

For parents with limited resources, one option is to rely on free child care. Among employed mothers with a preschool-age child, 42 percent of those with an annual family income under $15,000 paid for child care, compared with 70 percent of those with an annual income of $50,000 or higher. However, among low-income families, those headed by a single employed mother were the most likely to pay for care (57 percent).

Availability of Care. The availability of various child care arrangements is often cited as a third constraint on parents' ability to choose the child care they most want. The evidence on this issue is complicated. Analyses of parental report data from the National Child Care Survey indicate that differences in the availability of care options cannot explain income-linked patterns of reliance on different types of care. However, the limited number of programs that offer sliding-scale fees or accept subsidized children was found to restrict access for low-income children (Hofferth, 1995). This issue is elaborated in Chapter 5.

Relatives and friends who can provide child care may also be less readily accessible to families who need child care than many assume. Siegel and Loman reported that 67 percent of the families in their AFDC sample had no friend or relative, inside or outside their immediate household, who could provide child care; only 25 percent lived in households in which there were other adults present.

Transportation issues and city codes that prevent the establishment of child care centers in public housing projects were also cited by those who study AFDC populations as limiting the child care options that are accessible to low-income parents. Finally, irrespective of income, the low supply of center-based care for infants, toddlers, and school-age children, as

well as the severely restricted share of arrangements that care for children with disabilities or special health care needs, was noted repeatedly during the two workshops.

|

“PARENTS, AS A GROUP, ARE THE BEST TRUSTEES OF THEIR CHILDREN; THEY MUSTHAVE REAL CHOICES.” Jim Nicholie(comments at the workshop) |

In sum, when selecting child care, many working-poor and low-income families must chose from a seriously constrained set of options. They face a set of obstacles that derive primarily from the structure of low-wage jobs and from the meager incomes that these jobs provide. Their low incomes enable them to afford only free care by relatives and friends or very inexpensive care; their nonstandard and often rotating work hours restrict them to arrangements with flexible and weekend or evening hours of operation. These factors may also lead to greater reliance on multiple providers and expose young children to shifting child care arrangements.

When the portrait of dissatisfaction with child care among low-income parents is combined with this evidence of the difficulties that low-income families face as they attempt to combine work and child care, the compromises that many of these families must make become clear. Although low-income families' disproportionate reliance on relatives, for example, may reflect their most preferred choices given limited income and other factors, it may also reflect the only available option given financial, scheduling, and other constraints that are pervasive in these families' lives.

Taken as a whole, the data presented at the workshops suggest that, when informal arrangements are available, work well, and are dependable, they can offer working low-income families reassurance about their child's safety and the trustworthiness of the provider, as well as the low fees and flexibility that their jobs demand. When these arrangements prove difficult or unreliable, and as children grow past infancy, many of these parents shift (or want to shift) to formal arrangements —notably child care centers and preschools—that are often beyond their reach due to a variety of constraints. A shift from the irregular and part-time schedules of job training or school to the demands of full-time work can pose added burdens to the somewhat fragile, often part-time arrangements that are made with rela-

tives and friends. Other low-income parents whose first choice would be to place their children in a child care center or more formal family day care home cannot avail themselves of these options due to their higher costs and standard hours of operation.

The question this raises for public policy is whether these inequities in access to various child care options should continue given the probable costs associated with addressing them, or whether something should be done to provide working-poor and low-income families with the same range of child care options that families with higher incomes have and that may afford them access to the arrangements they feel are best for their children. At a minimum, it is important to determine whether the current structure of public child care subsidies reduces or aggravates the constraints that presently impinge on the child care choices of low-income families. These issues are examined in Chapter 5.