-

For those who traveled outside the United States, the length of their last trip for work or research was typically one month or less: 22 percent traveled for less than a week and 43 percent for 7 to 30 days. Another 19 percent traveled for 1 to 6 months and 17 percent for more than 6 months. Biological sciences, chemistry, and physics/astronomy had the highest percentages traveling for more than 6 months (between 19 and 20 percent).

-

For those not working or conducting research outside the United States, the reason most often cited (39 percent) was “not relevant to my career.” Other principal reasons for not traveling were “family-related reasons” (37 percent) and “no time” (36 percent). Also about one-third said they were “unaware of funding available” for work or research outside the United States.

-

The reason most often cited for not working or conducting research outside the United States varied by field. Computer science doctorates were most likely to say they had “no time” (47 percent); psychology doctorates were most likely to say it was “not relevant” (45 percent); and computer, health, and biological sciences doctorates were most likely to cite “family-related reasons” (between 41 and 42 percent).

-

Only 16 percent of scientists and engineers who had not worked or conducted research outside the United States said they were deterred by a “lack of foreign language skills” or that they were “concerned about losing my place in U.S. job market.”

Work-Related Training

-

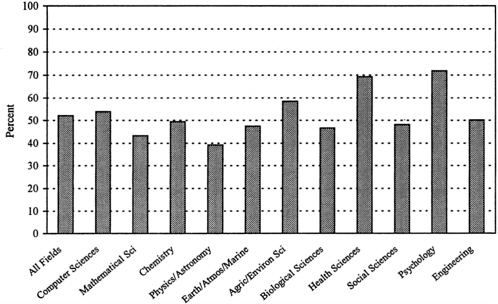

Fifty-two percent of science and engineering doctorates attended work-related workshops, seminars, or training in the year leading up to the survey (this excludes college courses or general sessions at professional meetings). By field, participation in work-related training ranged from a low of 39 percent among Ph.D.s in physics/astronomy to a high of 72 percent among psychology doctorates (see Table 40 ).

-

By and large, the training in which science and engineering Ph.D.s participated was technical training in their occupational field. This was tree for 78 percent of all who participated in work-related training, with variations by field from a low of 70 percent in physics/astronomy to 92 percent in psychology. Approximately 28 percent of those who attended training indicated they had attended management or supervisory training, a percentage that varied from a low of 17 percent for psychology to a high of 38 percent for chemistry.

-

The reason most often cited by doctorates for attending work-related training was to gain further skills or knowledge in their occupational field (92 percent). The second most frequent reason given for attending was that training was required or expected by their employers (33 percent).

FIGURE 17. Proportion of science and engineering Ph.D.s participating in work-related training between April 1994 and April 1995, by field.