2

The Center's Long-Term Strategic Plan

The Center requires a range of strategies to fulfill its mandate. Responding to management objectives and information needs demands flexibility. Long-term monitoring, by contrast, requires stable strategies for measurement and data management, while research programs should encourage innovation and creativity (Holling, 1998). Effective communication of scientific results depends on sound strategies for social learning and group decision-making (Gunderson et al., 1995; Lee, 1993; Walters, 1997).

These different types of strategies also require different types of evaluation (Mastrop and Faludi, 1997; Mintzberg, 1990; Mintzberg and Waters, 1998; Mintzberg et al., 1998; Westley, 1995). Monitoring plans lend themselves to formal evaluation of goals, protocols, and outcomes. Research programs require peer review. Evaluating the contributions of science to adaptive management is even more complex and may involve participant observation and surveys, as well as broad interdisciplinary reviews.

An overarching strategic challenge for the Center is thus to articulate the relationships among all these Program elements. Coordination is especially important in complex ecosystem-level programs. A strategic plan enables participants to envision common goals and agree on ways and means to achieve them. Where objectives compete with one another, it guides the collection of information on the likely consequences of alternative courses of action. It helps ensure that participants understand program goals, how those goals are to be achieved, and how unexpected

events and surprises can be addressed. In an adaptive management program, a strategic plan should articulate management goals and alternatives, providing a framework for interpreting experimental outcomes and evaluating trade-offs and compromises among alternative management actions.

This chapter reviews the general strengths and weaknesses of the Center's Long-Term strategic plans to address whether the Plan will be effective in meeting requirements specified in the Grand Canyon Protection Act, the Glen Canyon Dam Environmental Impact Statement, and the Record of Decision. It draws upon knowledge in the field of strategic management (Mastrop and Faludi, 1997; Mintzberg, 1990; Segal-Horn, 1998) and upon committee members' views.

THE CENTER'S STRATEGIC PLANS

The Center has prepared two long-term strategic plans. The first was written in May 1997 and adopted later that year. The second was drafted in November 1998 but not adopted. Debates about the revised Plan arose in part from policy issues that had been delayed until the Adaptive Management Program was established. Adoption of the 1997 Strategic Plan and rejection of the 1998 Plan may be indicative of changes within the Adaptive Management Program, as well as unresolved issues in the strategic plans.

The 1997 Strategic Plan aimed to "implement the adaptive management and ecosystem science approaches" called for in the Grand Canyon Protection Act, the Glen Canyon Dam Environmental Impact Statement, and the Record of Decision. It also proposed to "build upon the rich history of monitoring and research investigations developed by the Bureau of Reclamation and other organizations" (Center, 1997). The 1998 Strategic Plan stated some related aims: (1) to describe Center programs, (2) to develop the programs cooperatively with the Adaptive Management Work Group, and (3) to provide a guidance document for annual plans. Both documents included introductory chapters on institutions and the adaptive management paradigm (Table 2.1). They mentioned the Grand Canyon Protection Act, Glen Canyon Dam Environmental Impact Statement, and the Record of Decision that mandate the Adaptive Management Program, as well as the "Law of the River'' and other laws that constrain the Program (cf. Harris, 1998, for a broader inventory). The 1997 Strategic

TABLE 2.1 Structure of the Center's Strategic Plans

|

1997 Strategic Plan |

1998 Strategic Plan |

1999 Final Plans |

|

CH 1: History of Monitoring and Research in the Grand Canyon (6 pp) |

CH 1: Introduction— Purposes and Background (6 pp) |

CH 1: Introduction |

|

CH 2: GCMRC Program Justification and Mission (3 pp) |

CH 2: Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program (16 pp) |

CH 2: Philosophy of Monitoring |

|

CH 3: Science Programming within Adaptive Management (16 pp) |

CH 3: Management Objectives and Information Needs (7 pp) |

CH 3: Monitoring and Science Programs |

|

CH 4: Strategic Research Planning under Revised Paradigm and Institutional Constraints (12 pp) |

CH 4: Scientific Philosophy of Monitoring (11 pp) |

CH 4: Schedule and Budget |

|

CH 5: Defining Stakeholder Objectives and Management Information Needs (3 pp) |

CH 5: Monitoring and Science Programs (85 pp) |

|

|

CH 6: Monitoring and Science Programs (72 pp) |

CH 6: Schedule and Budget (3 pp) |

|

|

CH 7: Schedule and Budget (8 pp) |

Literature Cited |

|

|

Appendices |

Appendices |

|

Plan refers briefly to some aspects of federal trust responsibilities related to Indian tribes (cf. Tsosie, 1998, for broader treatment). Both documents address the Adaptive Management Program's geographic scope.

Chapters in the Strategic Plan on the Center's monitoring and research programs changed substantively from 1997 to 1998. The 1998 Strategic Plan gave less attention to the adaptive management paradigm and more to a "philosophy of monitoring," which indicated a growing emphasis on monitoring programs. The 1998 Strategic Plan combined cultural and socioeconomic programs under the heading of sociocultural resources in an effort to develop a broader and more integrated approach to assessing the social effects of dam operations. The 1998 Plan gave less attention to contingency planning than did the 1997 Plan, which seems unwise in light of the importance of preparing for "surprises" in adaptive management. Both the 1997 and 1998 Plans concluded with a brief chapter on schedule and budget. Neither plan included a discussion of staffing, management, or organizational strategies.

When the Adaptive Management Work Group removed Chapters 1–3 of the 1998 Plan—leaving only the chapters on philosophy of monitoring, resource programs, and schedule and budget—it raised both a potential problem and an opportunity. Separating science and adaptive management plans could increase problems of coordination and seems to run counter to the aim of coordinating science and policy. In the short term, however, separating the two sections presents an opportunity for stakeholder groups to clarify policy issues while the Center refines its monitoring and research programs. A draft outline of a "Guidance Document," prepared by the Technical Work Group in collaboration with the Office of the Solicitor, seems promising. It is planned to be more comprehensive and detailed than the Center's treatment of institutional issues (Technical Work Group, 1999; cf. Rogers [1998] on adaptive management programs).

In 1996, the National Research Council recommended that a planning group be established separate from the ecosystem study group to implement the Adaptive Management Program. The Transition Work Group (1995–1996) prepared plans separately from the Glen Canyon Environmental Studies. That separation of planning and study responsibilities dissolved during the Center's first two years, but may reassert itself with preparation of the Adaptive Management Program Guidance Document and the Adaptive Management Program Strategic Plan. When they are complete, however, the Guidance Document,

Adaptive Management Program Strategic Plan, and Center Strategic Plan must fit closely and interact well with one another.

STRENGTHS OF THE PLAN

Center scientists report that they have used the Strategic Plan to guide annual planning. Interviews with members of the Adaptive Management Work Group and Technical Work Group (the stakeholder groups) yielded a range of views of the Strategic Plan's utility. Some found it a useful reference and consulted it before meetings; others regarded it as overly expansive in scope and length; still others attached little importance to it. Aside from specific points of criticism, discussed later, there were no clear patterns of use and evaluation by different stakeholder groups.

The Center's efforts nonetheless have established the salience of strategic planning. Controversy over the 1998 Strategic Plan, while rooted in deeper unresolved policy issues, has had the positive effect of bringing those issues to the surface where they are now being addressed. Although the strategic plans rightly referred to policies that both enable and constrain the Center, the decision to move Chapters 1–3 to a Guidance Document would allow a more complete treatment of those chapters. Indeed, some branch of the Adaptive Management Program should undertake continuing institutional analysis. Previous National Research Council reviews of the Glen Canyon Environmental Studies included chapters on institutional issues that affect ecosystem monitoring and research, such as interagency relationships, policy changes, external reviews, and the roles of funding (Ingram et al., 1991; NRC, 1987, 1996a; cf. NRC, 1996b). Institutional and legal analyses are not explicitly incorporated in the Center's plans for adaptive management, socioeconomic research, or external review. The strategic plans were likewise on firm ground in attempting to situate monitoring and research within the broader context of adaptive management.

Strengths of the 1997–98 strategic plans to date are thus their roles in guiding annual plans, their attempts to coordinate science and adaptive management, and their salience in raising unresolved issues for discussion. Until recently, the entire responsibility for developing strategic plans fell on the Center. Although perhaps reasonable initially, a broader distribution of responsibility for preparation of strategic plans with

the Technical Work Group would enable the Center to focus more on monitoring and research.

WEAKNESSES AND ALTERNATIVES

The strategic plans have five general weaknesses: (1) insufficient definition of the Center's key strategic priorities to be addressed in the next five years, (2) inadequate discussion of geographic scope, (3) neglect of medium- and long-term time scales, (4) insufficient attention to the public significance of monitoring and research, and (5) omission of organizational and resource issues (e.g., staff and coordination).

Defining Key Strategic Priorities

The plans describe proposed monitoring and research programs without appraising: (1) what has and has not been accomplished, (2) challenges that stand out for the next five years, and (3) how proposed programs would build upon accomplishments and address failures. The committee recognizes there are many ways to articulate planning strategies, but considers these three elements crucial (cf, Mintzberg, 1998; Westley, 1995).

The 1997 Strategic Plan summarized the legacy of the Glen Canyon Environmental Studies, but did not analyze it or use it to justify the proposed Plan. Similarly, the 1998 Plan did not discuss what has and has not been accomplished since the Center was founded in November 1996. Among other things, the transition from the Glen Canyon Environmental Studies to the Center was completed. Charters were written, staff hired, adaptive management meetings convened, protocols defined, research grants awarded, a conceptual model built, logistics centralized, and a split of Lake Powell monitoring responsibilities negotiated. Stakeholders reported that the current situation is more collegial and promising than earlier, although some perceive that aspects of the process sometimes threaten to break down.

At the same time, monitoring programs have developed slowly. Although informal reasons were offered to explain the lack of implementation, these reasons could be addressed more explicitly in the Strategic Plan. The resource programs follow different approaches that are not well

coordinated. Although different approaches may be needed, a coordinating strategy is essential. Relations with stakeholder groups have proven time-consuming and sometimes difficult; program scope and responsibilities remain contested.

These accomplishments and problems define the Center's current situation. They indicate the challenges that must be addressed and suggest precedents, analogues, and alternatives for addressing them. The main challenge when the 1997 Plan was written was to establish the Center and define its programs. Now that the Center is established, what are the main challenges for the next five years? The 1998 Plan has elements of a "problem statement" in a section on current science needs and chapter on the philosophy of monitoring, but that chapter is more a list of factors to consider than strategic challenges to address.

Based on the committee's review of the strategic plans, the Center may wish to give greater attention to the following key challenges:

(1) implementing a long-term monitoring program, (2) clarifying the scientific basis of the existing adaptive management experiment, (3) coordinating monitoring and research in the resource program areas (and with related agency programs), (4) resuming socioeconomic research and decision analysis, (5) increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of Center participation in stakeholder processes, (6) implementing information management, and (7) contingency planning for environmental and policy surprises.

Although the Center may decide that other issues have even higher priorities, the point here is that it should identify the top strategic priorities for the next five years.

The aims and methods of strategy formulation are changing in ways that have a bearing upon the Center's plans. During the 1960s and 1970s, strategic planners emphasized optimization methods and measurable goals and outcomes as formal criteria for evaluating program performance. That formal approach may still be appropriate for monitoring programs where one wants to know whether wise choices have been made about what to measure, whether those measurements are accurate, complete, and systematically recorded, and whether a systematic plan has been established and followed to implement the monitoring program. By the 1980s, however, many formal strategic plans failed to materialize, or they constrained organizational changes necessary to improve perfor-

mance. Similarly, comprehensive plans for water development in the Colorado River Basin fell behind changing public attitudes and demands. Greater emphasis has subsequently been placed on strategies for adapting, learning, positioning, and envisioning (Mastrop and Faludi, 1997; Mintzberg, 1998; Westley, 1995)—all of which resonate closely with adaptive environmental management as it is developing in the Grand Canyon.

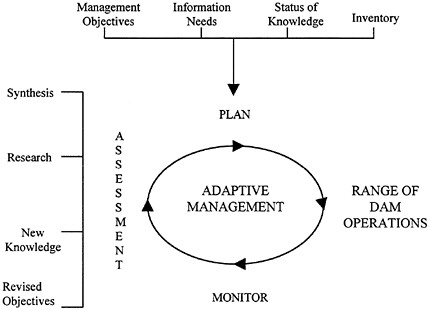

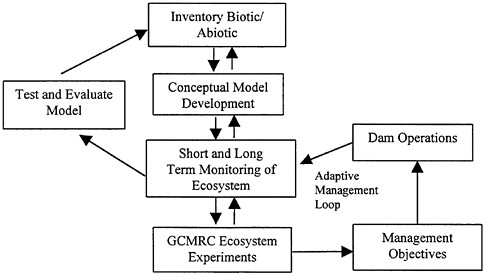

Westley (1995) distinguished "planning," "visionary," and ''learning" strategies, and stressed the importance of managing changes and cycles among these strategies. The Glen Canyon Environmental Studies had a visionary aspect that was later followed by greater emphasis on planning and learning through adaptive management. The overarching strategic challenge now is to coordinate these "planning," "visionary," and "learning" strategies (Mintzberg, 1998). The lack of clear coordination among the resource programs and adaptive management activities is evident in graphic representations in the strategic plans (Figures 2.1 and 2.2). These diagrams do not clearly depict the relationships among Program elements, processes, roles, and functions. Refining these graphic diagrams could help clarify a strategy for coordinating the Center's monitoring, research, and adaptive management roles. Other diagrams might focus on coordination of the five resource programs—physical resources, biological resources, cultural resources, socioeconomic resources, and information technology—that presently follow different outlines and approaches.

Geographic Scope

The geographic scope of the Adaptive Management Program has generated debate. Some stakeholders want sharper "sideboards" (boundaries), while others seek to include geographic linkages with upstream, downstream, and tributary processes.

The mandated focus of the Adaptive Management Program is on the effects of the Secretary's actions at Glen Canyon Dam on downstream resources. The Strategic Plan describes the Program's scope as the Colorado River ecosystem within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

and Grand Canyon National Park, which is defined as "the Colorado River mainstem corridor and interacting resources in associated riparian and terrace zones, located primarily from the forebay of Glen Canyon Dam to the western boundary of Grand Canyon National Park" (Center, 1998). The Program's lateral extent of the monitoring effort is defined by processes and conditions associated with dam discharges and river flows in connection with the Record of Decision. While this is defined "as the maximum regulated discharge and the inundated area for the annual predam peak flows," it is also noted that "it is prudent in some areas of the Colorado River ecosystem to include elevations above the stage associated with flows of 100,000 cfs" (all quotes from Center, 1998). The Programmatic Agreement for cultural resources management has included surveys that extend laterally to the 256,000 cfs "old high water zone" flood stage.

The strategic plans left the door open for selected studies in Lake Powell, tributary watersheds, comparable river reaches elsewhere in the basin, and Lake Mead, if they are related to effects on downstream resources. That openness, along with its implications for budget and management, became a source of controversy.

The first test case involved water quality monitoring in Lake Powell. Negotiation of a five-year Lake Powell monitoring program led to an agreement known as the "Lake Powell split," which divided monitoring responsibilities into the following categories (see also Appendix G):

-

"White"—Adaptive Management Work Group Management objectives and information needs that relate to downstream (below Glen Canyon Dam) effects and include monitoring and research activities conducted downstream of Glen Canyon Dam. They are funded by the Adaptive Management Program budget, with the scope of work reviewed by the Adaptive Management Work Group and Technical Work Group.

-

"Gray"—Adaptive Management Work Group management objectives and information needs that relate to downstream effects, but include monitoring and research activities conducted upstream of Glen Canyon Dam. These are part of the Adaptive Management Program and use its procedures, they are funded by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation or through the operation and maintenance budget or other sources, and the scope of work is developed by the Center and coordinated with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and other agencies.

-

"Black"—These are not directly related to downstream effects and include monitoring and research conducted upstream of the

-

Glen Canyon Dam. They are funded by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, other agencies, or other funding sources, and they are not formally a part of the Adaptive Management Program.

This classification indicates that the key issues are: Is there a physical connection between dam operations and downstream resources? Who conducts the research and monitoring and with what science protocols? Who pays for the research and monitoring? By addressing each of these issues, the three-category "Lake Powell split" moves beyond simple binary, but ecologically and institutionally flawed, distinctions between what is "inside or outside the box." It also represents a good example of adaptive management because it accommodates important resource linkages without losing geographic focus (U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, 1995). But it does not indicate how future decisions about geographic linkages will be made, or whether different criteria should be used for decisions about monitoring and research.

After reviewing these issues, the committee concluded that:

-

The Lake Powell split provides a useful model for addressing issues of geographic scope that will regularly arise in the future.

Issues related to the boundaries of the Adaptive Management Program will surely recur. These issues include interactions with the old high-water zone and upslope areas, seeps, and springs; tributary inputs of water, sediment, organic matter, and biota; interactions between the Grand Canyon riverine and Lake Mead delta ecosystems; regional hydroclimatic linkages with dam operations and their joint resource effects; comparisons with other dam-operation experiments, species recovery programs, and analogous reaches in the Colorado River Basin; and interregional comparisons of adaptive management experiments. By anticipating issues that will surely recur and by designing ways to efficiently address them, the Program could build upon experience gained with the Lake Powell split and address relevant resource linkages without losing its focus on the river ecosystem.

The Strategic Plan could make better use of previous National Research Council reviews and recent geographic and ecosystem management research on boundaries. The 1987 National Research Council review described boundaries similar to those currently proposed as "unnecessarily

and unreasonably restrictive" (NRC, 1987), while the 1996 review criticized the expansion of scope under Glen Canyon Environmental Studies Phase II as "unstable and expansive" (NRC, 1996a). These are the twin pitfalls of an overly narrow or broad geographic scope. The 1996 review also presented three criteria for defining geographic scope: management options, resources, and the ecosystem concept. The Lake Powell split succeeded by using all three criteria, but it also indicates that defining common stakeholder interests constitutes a fourth criterion.

The committee thus concluded that:

-

Rigid geographic boundaries will not serve the Adaptive Management Program well. After clearly defining the Program's geographic focus, decisions about geographic linkages must be made on a case-by-case basis, taking into account management options, ecosystem processes, funding sources, and common stakeholder interests.

Individual stakeholder concerns extend in many geographic directions, but adaptive management may help identify common concerns associated with dam operations and downstream resources. Tribal reports commissioned by the Glen Canyon Environmental Studies, for example, raise important questions about linkages between the Grand Canyon river ecosystem and wider landscapes (Ferguson, 1998; Hart, 1995; Roberts et al., 1995; Stoffle et al., 1994). Although these views have not been taken up in planning documents, they may be more widely shared by stakeholder, public, and scientific groups than is presently recognized (Frederickson, 1996; Morehouse, 1996).

On a scientific level, the Center has collaborated effectively with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientists on the implications of the 1997 El Niño for dam operations and downstream resources (cf. Pulwarty and Redmond, 1997).

The committee concluded that:

-

The Strategic Plan could use the Center–National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration collaboration as one model for research on regional geographic linkages that have effects on downstream resources, and for interagency coordination. Other models include co-financing of research on events and phenomena that, when combined with dam operations, have joint downstream effects relevant for adaptive management.

Research on geographic boundaries and ecosystem management indicates that no boundary satisfies all functions or purposes (Forman, 1996; Keiter, 1994; Morehouse, 1996; Prescott, 1987). It is not likely that a single boundary rule will be appropriate in all policy or management contexts, and it would constitute poor science and management to allow a predetermined rule to rigidly constrain the scope of science and monitoring. Rather, a procedure is needed to decide individual issues on their merits and their relevance for understanding the effects of dam operations on the Grand Canyon ecosystem. Boundaries help focus a program, but they should be used to guide the manner in which resource linkages are investigated rather than preclude investigation. A procedure and criteria for managing boundary issues could help the Center move beyond "expand–contract" struggles to a more efficient and scientifically reasonable treatment of resource linkages that arise. In addition to whether or not the proposed research falls within the Adaptive Management Program, and who is to pay for it, the procedure should indicate who decides and how the decision is made. Local boundary issues that arise in research proposals might be delegated to the Center and peer review panels, while regional research and monitoring activities might involve higher levels of oversight and approval.

It is encouraging to note that the draft outline for the Technical Work Group's Guidance Document (Technical Work Group, 1999) refers to adaptive management in other parts of the Colorado River Basin and in other regions of North America. The Center should maintain an awareness of experiments in related and comparable basins to ensure a broad range of alternatives and lessons from past experiences when planning for Grand Canyon ecosystem management. This should include the Upper Colorado River Basin Recovery Implementation Program, the San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation Program, and the Multispecies Recovery Program in the Lower Colorado River, since all fishes of interest in the Grand Canyon are under management both up- and downstream from Lake Powell in the Green, San Juan, and Colorado rivers. It should also include a strategy for drawing lessons from adaptive management and dam operations in other regions, such as the Columbia River Basin, the Everglades, and the Upper Mississippi River Basin (Gunderson et al., 1995; Independent Scientific Group, 1996; Independent Scientific Group, 1996; Lee, 1993; NRC, 1996b; Sit and Taylor, 1998; Volkman, 1997; Walters, 1997; Walters et al., 1992). Individual Center scientists currently follow

these other experiments, but there is nothing in their job descriptions, mission statement, or budget to sustain those personal commitments.

The committee concluded that:

-

The Strategic Plan should indicate how the Center would draw insights from adaptive management in other regions, especially those involving water resources management.

A large program of comparative research is not envisioned, but rather a creative strategy and modest resources for drawing practical lessons from related experiments. Leading experts spoke and led the second Adaptive Management Work Group meeting in January 1997, and also lead the conceptual modeling project. These are good examples of communication that helps maintain a creative flow of ideas and avoids common pitfalls in adaptive management.

Medium and Long Time Scales

The Strategic Plan spans five years, which may be "long" for administrative purposes, but it is too short for ecosystem management. The 1998 Plan lists time scales from hourly to interannual and "pre-dam versus post-dam time periods." Although this last time scale is longer than the strategic planning period, the Plan does not explicitly discuss decadal or multidecadal time scales, nor does it address the "perpetuity" for which Grand Canyon National Park was established. These medium and long time scales are relevant and essential for planning, ecosystem monitoring, and adaptive management.

The multidecadal life span and population dynamics of fish species such as humpback chub and razorback and flannelmouth suckers, for example, influence the design of monitoring programs today. As Lee (1993, p. 63) states, "The time scale of adaptive management is the biological generation rather than the business cycle, the electoral term of office, or the budget process." Monitoring of long-lived species and decadal ecosystem processes entails decades of data collection and design of experiments of similar duration. Social changes over the same time scales are analyzed in histories of western water management but rarely considered in the design of monitoring programs (Lee, 1993; NRC, 1968; Pisani, 1992). To understand how changes in downstream resources are

experienced and evaluated, those social effects must be monitored and analyzed.

Major institutions also change on decadal time scales. The 1998 Strategic Plan was criticized for straying into policy issues related to the Grand Canyon Protection Act, the Glen Canyon Dam Environmental Impact Statement, the Record of Decision, and the Law of the River. But these issues and changes bear directly on Center programs. During the course of this review, for example, the U.S. National Park Service considered wilderness designation for as much as 94 percent of Grand Canyon National Park, which would affect the conduct and costs of monitoring and research; biological opinions for endangered species were reviewed; and stakeholders debated the relative importance of sections 1802, 1804, and 1805 of the Grand Canyon Protection Act.

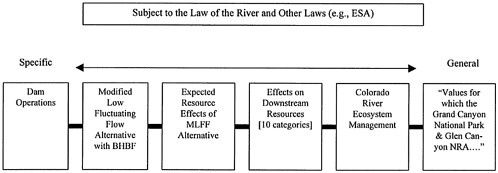

Section 1804 of the Act focuses on "the Colorado River downstream of Glen Canyon Dam." Section 1802 refers more broadly to the "values for which Grand Canyon National Park and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area were established, including, but not limited to natural and cultural resources and visitor use," and section 1805b to the "effect of the Secretary's actions on the. . .resources of Grand Canyon National Park and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area." In the short-term (inter-annual), these might be regarded as competing principles, but a longer-term, decadal perspective would reveal how they are logically related to one another (see Figure 2.3, and see discussion in Chapter 3).

Similarly, a historical perspective on the Law of the River indicates that major changes have occurred on a decadal frequency during the twentieth century (e.g., Harris, 1998). To design a long-term monitoring system without considering the likely occurrence and uncertain implications of such social and institutional changes and trends could reduce the Program's robustness and flexibility.

The committee concluded that:

-

The Strategic Plan should relate five-year planning to multidecadal planning, ecosystem monitoring, and adaptive management.

Public Significance of Center Programs

The Strategic Plan should consider the broader public context and

significance of Grand Canyon monitoring and research. Official stakeholders encompass a complex array of local to national interests, including federal agencies, Indian tribes, basin states, power consumers, and nongovernmental organizations. Public interests in "science" itself are not explicitly represented. The growing emphasis on science in adaptive management involves a broader, nationwide public movement to address resource management problems as science-policy experiments (Lewis, 1994; Tarlock, 1996).

The potential significance of these science-policy experiments includes and extends beyond the concerns of officially recognized stakeholders. In addition to its status as a national park held in trust for the citizenry of the United States, the Grand Canyon is a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site with international and global significance. At every level of adaptive management, from ad hoc committees to the Secretary's actions, an aim of the scientific monitoring and research programs is to clarify and secure the "common interest" in the Grand Canyon ecosystem (Brunner and Clark, 1997).

The Center's strategic plans give little attention to public interest in science-based approaches to resource management. They are certainly open to public involvement, outreach, and education, but they have not explicitly made plans or budgets to respond to or encourage these activities. Although this is not surprising for a new program, a long-term strategic plan should anticipate the prospect of expanding public interest and involvement. An example is underway in the Upper Mississippi River Basin, where a program of "citizen science" (i.e., public education and museum activities) is envisioned to lay the foundation for broad social decision-making in future decades (S. Light, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, personal communication, 1998).

The committee concluded that:

-

The Strategic Plan should explicitly recognize and speak to public interests in Grand Canyon monitoring and research and should anticipate programs of public education, outreach, and involvement.

Over the long term and therefore in its Strategic Plan, the Center should also strive to use monitoring and research to clarify common interests in downstream resources. While the Adaptive Management Work Group is responsible for articulating the common interest in man

agement of Glen Canyon Dam and the Grand Canyon ecosystem, the Center is responsible for stewarding emerging public interest in science-based approaches to dam and ecosystem management.

Organizational Resources as Strategic Planning Issues

The strategic plans include brief chapters on ''Schedule and Budget," but do not include discussions of the staffing, administration, or budget needed to achieve the plans' goals. These omissions contribute to ambiguity in how plans will be implemented and to continuing concerns about budget increases, which results in uncertainties for programs and personnel. The lack of sufficient cost and administrative information was a criticism voiced in a National Research Council review of the initial draft long-term monitoring plan (NRC, 1994).

The inclusion of anticipated resource needs for the Center in its Strategic Plan is very important. The 1997 Plan was more explicit on this point than the 1998 Plan. Neither of the strategic plans discusses staffing issues and needs, which are critical issues for both the Center and Adaptive Management Program. Questions of what the Center should do are inextricably linked with questions of who should do it (and how many staff are necessary) and should therefore be addressed. Some attention should also be paid to securing longer-term funding and contingency planning to eliminate the negative impacts of uncertain funding cycles on new and continuing science programs. For example, in the fiscal year 1999 budget cycle, the Upper Colorado River Recovery Implementation Program sought appropriations of $46 million to be spent over the next five-year period. At the same time, contingency planning is needed to respond to environmental and policy surprises (e.g., tributary flood events, and the proposed wilderness designation for Grand Canyon National Park).

SUMMARY

The question of whether the Strategic Plan will be effective in meeting the requirements specified in the Grand Canyon Protection Act, the Glen Canyon Dam Environmental Impact Statement, and the Record of Decision can be addressed in a preliminary way from the evidence above. The strategic plans indicate that Center scientists have a keen ap-

preciation of these requirements. They cite relevant policy documents and grasp their logic, spirit, and limits. The strategic plans have been designed to fulfill those requirements, and the committee concluded that they have a good chance of success.

How well they meet those requirements, however, depends upon how clearly the plans define the Center's most pressing challenges for the next five years. This depends upon a wise combination of focus and flexibility when addressing issues of geographic scope, building upon previous experience when possible. It requires a broader view of time scales and the emerging public interest in scientific monitoring and research. It depends upon a pragmatic strategy for marshalling organizational resources in a turbulent environmental and policy context. Finally, and perhaps most important, it depends upon an innovative strategy for assuring independent scientific inquiry in a program of adaptive management.