CHAPTER FIVE

What Does TIMSS Say About School Support Systems?

Just as curriculum and instruction affect student performance, the broader culture of a school and a society matters as well. Aspects of this culture include the preparation and support of teachers; attitudes toward the profession of teaching; the attitudes of teachers, students, and parents toward learning; and the lives of teachers and students, both inside and outside school. The TIMSS achievement tests, questionnaires, and case studies of the educational systems in Japan, Germany, and the United States all make the same point: these elements of the broader educational system and society can have an important influence on what students learn.

Many aspects of this broader culture are outside the control of teachers, school leaders, and policymakers. Nevertheless, the results of TIMSS point to differences among countries in school cultures that can be altered. These results suggest that school cultures are not given but are created and re-created by the decisions

that teachers, administrators, students, and others make about how to organize teaching and learning.

As with the curriculum and instructional practices, the national standards in mathematics and science emphasize the importance of school support systems embedded in the broader culture. The science standards have separate sets of standards for science education systems and for the professional development of science teachers, which are both key elements of school support systems. Similarly, the volume Professional Standards for Teaching Mathematics (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 1991, p. 2) is based on two premises: "(1) Teachers are key figures in changing the ways in which mathematics is taught and learned in schools. (2) Such changes require that teachers have long-term support and adequate resources."

This chapter does not present particular aspects of the school culture as either good or bad. Rather, it describes a range of options across various dimensions of this culture. The aim is to bring these options to the attention of those responsible for making systemic informed attempts to improve school systems and academic achievement.

This chapter also is selective in its examination of school support systems, examining four particularly important influences on teaching and learning. The first section looks at time—primarily the structuring of teachers' time on a day-to-day level and its impact on collegiality among teachers. The second section examines teacher learning, including preservice preparation, new teachers' experiences, and ongoing professional development. The third section considers cultural influences on teaching, both at the school level and more broadly. The fourth section focuses on students' attitudes toward mathematics and science.

TEACHERS' TIME

For teachers across all countries, time is both a resource and a constraint. Through the TIMSS questionnaires, teachers outlined how they spend their time during the school week. The case studies of the educational systems in the United States, Germany, and Japan flesh out the picture of teachers' uses of time. While TIMSS did not draw conclusions about the uses of time in U.S. schools, the study demonstrates significant differences among countries that may bear closely on student achievement.

Time Pressures

The nature of teachers' work differs from country to country and among schools, but teachers everywhere say they are very busy.

According to questionnaire responses, teachers routinely spend time outside the formal school day to prepare and grade tests, read and grade student work, plan lessons, meet with students and parents, engage in professional development or reading, keep records, and complete administrative tasks. Fourth-grade teachers in the United States, for example, spent an average of 2.2 hours each week outside the formal school day preparing or grading tests, as well as 2.5 hours planning lessons. Similarly, each week on average their Japanese counterparts spent 2.4 hours on tests and 2.7 hours on lesson plans outside the school day.

|

QUESTIONS RELATED TO TEACHERS' TIME

|

Recordkeeping and administrative tasks also took the U.S. teachers more than 3.5 hours each week and their Japanese peers just over 4 hours outside school (Martin et al., 1997, p. 137).

The TIMSS case studies reveal sharp contrasts among Germany, Japan, and the United States in the organization of school time, both daily and yearly (Table 5-1). Of the three, Japanese teachers have the longest official workday (8 to 9 hours, despite a slightly later average start time each day) and the longest work year (240 days). U.S. teachers put in longer official days than their German counterparts (7 to 8 hours in the United States and 5 to 5.5 hours in Germany) but have comparable work years (180 and 184 days, respectively).

Teachers also spend their time in school in somewhat different ways. Japanese teachers fulfill a broader range of in-school responsibilities than do German and U.S. teachers. For example, not only do they take turns supervising the playground, they also supervise lunch in their homerooms and the cleaning of a portion of the school each day (Stevenson and Nerison-Low, 1997, pp. 127–133).

Time to Collaborate

One of the most significant distinctions between Japanese and U.S. teachers' days is how much time they have to collaborate with colleagues (Tables 5-2a and 5-2b). Compared with Japanese teachers as a whole, U.S. teachers across all grade levels spend more of their assigned time in direct instruction and less in settings that allow for professional development, planning, and collaboration. As noted above, Japanese teachers also spend more time at school over the course of the day, which offers additional opportunities for collaboration. In addition, Japanese teachers often have the opportunity to observe each other's classes throughout the day (Kinney, 1998, pp. 223–227).

In Japan, teachers' time is structured in ways that enable collaboration. For example, in Japan, even brief breaks between classes become occasions for conversation. Instead of the 5 minutes between classes allowed in many U.S. schools, in Japan there might be 10- and sometimes 15-minute breaks between classes (Kinney, 1998, p. 225).

For the Japanese teachers observed in the case study, the boundaries between personal life and professional time often were not clear (Kinney, 1998, pp. 190–194). Many were heavily involved in school life not only in formal ways but also through informal study groups and other networks that strengthened their professional ties. While some Japanese teachers had

TABLE 5-1 Typical Features of a Teacher's Schedule in Japan, Germany, and the United States

|

|

Japan |

Germany |

United States |

|

School days per year (approximate) |

240 |

184 |

180 |

|

Begin school day |

8:00 a.m. |

7:30 a.m. |

7:30 a.m. |

|

Classes end |

3:30 p.m. |

12:00 or 1:30 p.m. |

2:45 p.m. |

|

End of day at school |

4:00 p.m. or later |

12:30 to 1:30 p.m. |

4:00 p.m. or later |

|

Do schoolwork at home |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Staff meetings |

|||

|

Daily |

Yes |

— |

— |

|

Weekly |

Yes |

— |

Varies |

|

Monthly |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Supervise |

|||

|

Lunch |

Daily in homeroom |

— |

Rotating |

|

Playground |

Rotating |

Rotating |

Rotating |

|

Opportunity for collegial interaction |

|||

|

Teachers' workroom |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Lounge and hallways |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Source: Stevenson and Nerison-Low, 1997, pp. 127–128. |

|||

family obligations that bounded their work day, for many, teaching, study, research, travel, and hobbies blended together and reinforced each other.

In contrast to Japan, Germany structures school time in ways that tend to isolate teachers from one another (Stevenson and Nerison-Low, 1997, pp. 131–132). Schedules in Germany require that the vast majority of teachers spend only the morning at school. Teachers normally go home soon after the students at midday, and they are expected to accomplish much of their planning and professional development outside the school day. In addition, with 23 to 27 periods per week in those half-day sessions, the schedule is packed, leaving teachers little time for the exchanges that punctuate Japanese teachers' days. While many Japanese teachers build lesson planning, grading, and other school-related work into their time in the building, German teachers typically reported doing their out-of-class work at home.

TEACHER LEARNING

Preservice teacher education and later professional development are important factors contributing to the learning environment of students. Countries vary markedly in how they balance preservice and in-service education, where they locate professional development opportunities, whose expertise they consider most important to professional development, and the ways in which teacher learning unfolds, both formally and informally.

TABLE 5-2a Reports from Teachers Responsible for Teaching Science at the Fourth-Grade Level on How Often They Meet with Other Teachers to Discuss and Plan Curriculum or Teaching Approaches

|

|

% of Students Taught by Teachers Who Meet with Their Colleagues |

|||

|

Country |

Never or Once/Twice a Year |

Monthly or Every Other Month |

Once, Twice, or Three Times a Week |

Almost Every Day |

|

Australia |

7 |

32 |

51 |

10 |

|

Austria |

19 |

23 |

36 |

22 |

|

Canada |

33 |

34 |

27 |

6 |

|

Cyprus |

13 |

13 |

64 |

11 |

|

Czech Republic |

3 |

13 |

31 |

52 |

|

England |

4 |

12 |

75 |

13 |

|

Greece |

32 |

26 |

26 |

16 |

|

Hong Kong |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Hungary |

2 |

13 |

45 |

41 |

|

Iceland |

16 |

13 |

69 |

1 |

|

Iran, Islamic Republic |

4 |

26 |

54 |

16 |

|

Ireland |

46 |

42 |

7 |

5 |

|

Israel |

10 |

42 |

41 |

7 |

|

Japan |

5 |

14 |

61 |

20 |

|

Korea |

17 |

24 |

41 |

18 |

|

Kuwait |

7 |

1 |

75 |

17 |

|

Latvia (LSS) |

14 |

28 |

32 |

26 |

|

Netherlands |

36 |

33 |

29 |

2 |

|

New Zealand |

10 |

17 |

60 |

13 |

|

Norway |

4 |

7 |

82 |

7 |

|

Portugal |

10 |

62 |

17 |

11 |

|

Scotland |

9 |

37 |

40 |

14 |

|

Singapore |

11 |

64 |

21 |

4 |

|

Slovenia |

4 |

33 |

31 |

32 |

|

Thailand |

62 |

23 |

13 |

1 |

|

United States |

19 |

21 |

49 |

11 |

|

Source: Martin et al., 1997, p. 139. Note: In most of the TIMSS countries, primary school classes are taught by a single teacher who is responsible for teaching all subjects in the curriculum. However, in a minority of countries, primary school students have different teachers for mathematics and science. In both Tables 5-2a and 5-2b, countries shown in italics did not satisfy one or more guidelines for sample participation rates, age/gender specifications, or classroom sampling procedures. A dash indicates that data are not available. |

||||

Teacher Preparation

The length of teacher training varies widely from one country to another. For population 1 and 2 teachers, required training in different countries ranges from only two years of postsecondary schooling to as many as six years (Martin et al., 1997, p. 129). Some countries require university preparation, others prescribe preparation in a teacher training institution,

TABLE 5-2b Reports from Mathematics Teachers at The Eight-Grade Level On How Often They Meet with Other Teachers in Their Subject Area to Discuss and Plan Curriculum or Teaching

|

|

% of Students Taught by Teachers Who Meet with Their Colleagues |

|||

|

Country |

Never or Once/Twice a Year |

Monthly or Every Other Month |

Once, Twice, or Three Times a Week |

Almost Every Day |

|

Australia |

10 |

50 |

30 |

9 |

|

Austria |

20 |

37 |

36 |

6 |

|

Belgium (Fl) |

48 |

28 |

21 |

3 |

|

Belgium (Fr) |

22 |

34 |

38 |

7 |

|

Canada |

38 |

25 |

31 |

6 |

|

Colombia |

24 |

30 |

42 |

4 |

|

Cyprus |

4 |

6 |

67 |

22 |

|

Czech Republic |

22 |

23 |

34 |

20 |

|

Denmark |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

England |

8 |

41 |

51 |

0 |

|

France |

45 |

22 |

29 |

4 |

|

Germany |

32 |

31 |

22 |

15 |

|

Greece |

43 |

26 |

26 |

6 |

|

Hong Kong |

33 |

48 |

19 |

0 |

|

Hungary |

9 |

16 |

39 |

35 |

|

Iceland |

42 |

29 |

29 |

0 |

|

Iran, Islamic Republic |

18 |

37 |

34 |

11 |

|

Ireland |

59 |

25 |

14 |

2 |

|

Israel |

25 |

34 |

37 |

4 |

|

Japan |

24 |

29 |

46 |

1 |

|

Korea |

22 |

26 |

37 |

15 |

|

Kuwait |

10 |

2 |

66 |

22 |

|

Latvia (LSS) |

28 |

46 |

16 |

10 |

|

Lithuania |

25 |

36 |

24 |

14 |

|

Netherlands |

13 |

65 |

21 |

2 |

|

New Zealand |

6 |

45 |

43 |

6 |

|

Norway |

7 |

20 |

65 |

8 |

|

Portugal |

8 |

69 |

18 |

5 |

|

Romania |

12 |

58 |

14 |

16 |

|

Russian Federation |

12 |

57 |

20 |

11 |

|

Scotland |

7 |

12 |

74 |

8 |

|

Singapore |

25 |

61 |

21 |

3 |

|

Slovak Republic |

4 |

23 |

35 |

39 |

|

Slovenia |

5 |

53 |

18 |

24 |

|

Spain |

17 |

48 |

32 |

2 |

|

Sweden |

9 |

19 |

46 |

26 |

|

Switzerland |

36 |

32 |

30 |

2 |

|

Thailand |

53 |

17 |

23 |

6 |

|

United States |

37 |

31 |

26 |

6 |

|

Source: Beaton et al., 1996a, p. 142. |

||||

|

QUESTIONS RELATED TO TEACHER PREPARATION AND TEACHER DEVELOPMENT

|

and some require both. Most countries require a teaching practicum, and many require an examination or evaluation for certification (Mullis et al., 1997, p. 144; Beaton et al., 1996a, p. 132).

In the United States teacher preparation tends to be relatively extended compared with the teacher education required internationally, and it takes place in a variety of programs. Candidates learn to teach in university programs (typically a two-year liberal arts foundation followed by two years of professional preparation), postbaccalaureate and five-year programs, and alternative certification routes (Stevenson and Nerison-Low, 1997, p. 121). Education courses make up a greater share of the coursework of those studying to teach elementary school than of those preparing to teach secondary school: 50 of 125 credits, on average, for future elementary teachers and 26 of 125 for secondary teachers. Student teaching experiences in the United States range from 6 to 18 weeks and have no uniform length or shape. While U.S. teachers stress the importance of student teaching to their learning, they often criticize the quality of supervision they receive.

Germany puts future teachers through a longer period of formal preparation than the

TABLE 5-3 Comparison of Teacher Training Requirements

|

Japan |

Germany |

United States |

|

• Four years at a teachers' college or university |

• Four to five years at a university |

• Four years at a college or university |

|

• Three to four weeks of practice teaching |

• Two years of practice teaching |

• One semester of practice teaching |

|

• Prefectural certification exam |

• First state exam |

• State certification exam |

|

• New teachers receive one year of in-school training under mentor and supplemental training in resource centers |

• Second state exam |

• Certification may be contingent on evaluation of first year of classroom work |

|

Source: Stevenson and Nerison-Low, 1997, p. 116. |

||

United States does (Table 5-3). Certification requirements depend in part on the level of school at which one will teach, but the typical pattern is four or five years of university preparation followed by two years of paid student teaching. Students pursuing certification to teach in one of Germany's academically selective high schools prepare in two subject areas and take extra courses in these areas, while those bound for academically less intense schools take more courses in general education (Milotich, 1996, p. 315). In Germany, university preparation is only the beginning of formal training. Preservice teachers take two certification examinations, one following university coursework and a second after the two years of student teaching. The first exam includes a written thesis in one's subject area or in education, written and oral examinations, and sometimes a practical exam (Milotich, 1996, p. 315). As many as two-thirds of students who begin university teacher preparation change career goals before reaching the first examination; among those who do take the first examination, ''quite a few'' never embark on student teaching (Milotich, 1996, p. 318). Student teaching, a phased experience, combines seminar study, classroom observation, assisted teaching, independent teaching, and preparation for the second state examination. Students work with mentor teachers in their subject areas as well as with seminar instructors who are themselves practicing teachers. The second state exam is judged by a committee of teachers, mentors, seminar instructors, and a representative of the state ministry of education. The committee weighs factors that include reports by mentor teachers; the candidate's written thesis on lessons and units taught; and an oral examination on methodology, subject-related issues, or school laws and organization (Milotich, 1996, p. 321).

Germany's approach seems starkly different from U.S. approaches, but teachers in the two countries give surprisingly similar assessments of their preparation. German teachers said their university training was too theoretical, teacher preparation programs were fragmented, and inadequate guidance was offered. They considered student teaching very helpful but vulnerable to the weaknesses of mentors and seminar instructors. Many teachers said their mentors were ill prepared to help novices. Germany's mentor teachers receive no release time or compensation for their work.

In Japan, university graduates must take a highly competitive examination to qualify for a teaching position. Field experience for preservice teachers typically lasts a mere two to four weeks, but beginning teachers value it highly. The experience is seen less as an opportunity to put academic knowledge into practice than as a chance for learning the patterns of interaction that exist between teachers and pupils. While the Japanese preservice system seems to offer beginners little sustained support for learning their profession, the Japanese approach views preservice preparation as only a small beginning in a career launched and marked by mentoring relationships.

Professional Development for New Teachers

Professional development of teachers is as different among countries as teacher prepara-

tion. The case studies portray sharply different images of what professional development comprises, where and when it occurs, and the assumptions that underlie it. Not only do Germany, Japan, and the United States structure professional development opportunities differently, but differences in practice—how teachers experience professional development—exceed the differences in policy.

The United States appears to offer a less formal or coherent system of professional development than do Germany and Japan. Beginning teachers are expected immediately to take on the same duties and schedules as their more experienced peers, often without formal assistance. Although mentoring of first-year teachers is on the rise as official policy, there is no consistent approach to it. Communities vary greatly in such factors as the preparation and support given mentors and expectations for collaboration between mentors and novices.

Germany and Japan have more formal systems of induction to teaching. Just as Germany requires all new teachers to participate in a two-year, field-based student teaching experience, Japan assigns a mentor and requires additional study for first-year teachers. The German and Japanese approaches represent national policies that support the new teacher's transition from university preparation to work in schools. The German and Japanese approaches differ greatly from each other, however.

Germany's program is clearly a student teaching experience. While participants are paid (albeit less than licensed teachers), hired by districts, and work in schools, their experience—both the classroom experience and the associated seminar study and examination preparation—is preparation, almost always for a position not in the school in which they are student teaching. While the teachers interviewed stressed the importance of the experience to their learning, they spoke less about the value of learning from other teachers and more about the importance of being grounded in practice (Milotich, 1996, p. 320).

Japan in the past decade has mandated an intensive mentoring and training program for all teachers in their first year on the job, a system reflecting the culture's widespread assumption that elders should guide novices. New teachers in their first year have at least 60 days of closely mentored teaching and 30 days of further training at resource centers run by local and prefectural boards of education. To allow for these activities, their teaching load is reduced (U.S. Department of Education, 1996, p. 51). Junior high and high school novices teach about 10 hours a week and go to the resource center one day each week. Of the 90 days of training provided to the newest teachers, 60 occur within the school (Kinney, 1998, p. 204). In its interweaving of practice and study and its practice of learning from colleagues, Japan's orientation to teacher learning seems consistent with the country's norms of professional development in many other fields.

Professional Development over the Career

Japan displays a systematic orientation to lifelong learning, in contrast to the more ad hoc approaches taken by Germany and the United States to the professional development of experienced teachers.

Japanese teachers rotate among schools every six years, often changing grades as well.

This norm builds in new challenges for teachers, creates career cycles unlike those abroad, and constructs school cultures different from the relative stability that prevails in Germany and the United States. While remaining in a single school might be more comfortable, teachers believe it produces less growth. Similarly, Japanese teachers believe that teaching students of different ages enables them to understand children better (Kinney, 1998, pp. 209–211).

In addition, Japanese teachers in some areas engage in mandatory professional development away from their school in their sixth, tenth, and twentieth years. Reflecting on these experiences in the case study interviews, seasoned teachers suggested that the "content of the training was not always as important as the chance to mingle with peers and reflect upon one's job" (Kinney, 1998, p. 207).

Professional enhancement opportunities are quite varied in Japan. They range from formal training at local resource centers to voluntary mentoring and peer observation to lively teacher-organized informal study and action-research groups—a mode of professional development that teachers value highly. The case study found, in fact, that "most teachers voluntarily participate in teacher-run subject study groups that meet in the evening" (Kinney, 1998, p. 208) to examine videotapes of practice, study new curricula, discuss textbooks, and so on. Some communities offer professional development fellowships or sabbaticals to support teacher research in an "in-country exchange study," with teachers released for a few weeks from their school to travel to study in a place they choose. A range of national, regional, and local study grants send teachers traveling domestically and abroad (Kinney, 1998, p. 205). All these practices reflect the assumption that teachers need broad knowledge.

Interestingly, German teachers tended to say that a critical part of success in teaching is "an openness and willingness to learn" (Milotich, 1996, p. 310). Yet they did not share Japanese teachers' assumption about the centrality of peers to one's learning. Instead, in Germany, "some teachers, in talking about how such learning occurred, referred to journals that they read regularly. Science teachers, in particular, talked about the importance of keeping current with the subject matter" (Milotich, 1996, p. 310).

The case study report on Germany concludes that "teachers at all stages of their careers lack formal support" (Milotich, 1996, p. 326). There are many "state-sponsored institutions and academies offering continuing-education courses for experienced teachers" (Milotich, 1996, p. 329). In addition, schools bring in "experts" to address issues identified as problems in the school. Continuing education, however, is not required in most states, and participation seems to be highest among less experienced teachers.

U.S. schools and school districts offer a range of staff development programs, but these tend to be short-term, vary widely in focus, and often appear to teachers as a menu of unrelated opportunities for stimulation or growth. Districts vary in the degree to which they try to induce teachers to take advantage of these opportunities. Although some districts engage in more systematic efforts at sustained profes-

sional development, short-term workshops remain the dominant format. Teachers in the case study were "only peripherally aware" of approaches to professional development that grow out of practice and allow teachers "to study and improve their own practice" (Lubeck, 1996, p. 259).

While the case studies suggest generalizations, it would be a mistake to regard cultural differences as rigid determinants of teachers' experiences. These experiences are dynamic, not fixed. Japan's recent mandates for formal teacher support, Germany's newest approaches to teacher preparation, and emerging U.S. policies on mentoring all demonstrate that the context of professional development is changing and that teachers of different ages have had different experiences as approaches to professional development have evolved.

CULTURAL INFLUENCES ON TEACHING

Arrangements of teachers' time and approaches to teacher learning contribute greatly to school culture, but culture encompasses more subtle factors as well. Without labeling these factors as either good or bad, it is useful to look at the range of choices that school personnel make in various dimensions of schooling. Through these choices, school personnel situate their schools at particular points along continuums of cultural variables. This section examines two such continuums illuminated by TIMSS. The first describes how teachers work—the continuum from community to autonomy—while the second describes their status—the continuum from professional to skilled worker.

Underlying these continua are striking international similarities in how teachers view their work. The salient picture that emerges from the case studies is of people who are dedicated to teaching but who, especially in the United States, are enduring frustrations and even fatigue in their professional lives. In other countries the frequency and intensity of these problems tend to be less serious, but they are equally disturbing to the teachers involved. Many teachers believe the demands they face have increased in recent years, and high school teachers "find the heightened emphasis on [high-stakes] examinations to be among the

|

QUESTIONS RELATED TO CULTURAL INFLUENCES ON TEACHING

|

most troublesome demands currently made of teachers in all three countries" (Stevenson and Nerison-Low, 1997, p. 140).

The Continuum from Community to Autonomy

The challenge of school leadership is to maximize the impact of individual strengths and the collective capacity of the instructional staff. How to do both at once is a challenge every school faces, and TIMSS describes very different approaches and decisions that schools make in this regard.

Japanese teachers have desks in a shared teachers' room, and teachers with common assignments may have neighboring desks in order to exchange ideas, plan together easily, and more naturally and frequently interact (Kinney, 1998, pp. 220–225). This shared office space opens some part of teachers' work to others' view, which can, at different times, be either enabling or constraining.

This arrangement contrasts with teachers' lounges and staff rooms, the common situation in the United States and Germany, where there is no structure of desks or space that supports interactions around teaching. Some U.S. and German schools provide spaces where teachers can and do come together meaningfully, but these are the exceptions, the case studies indicate. German teachers have little time for interaction during the day, and most U.S. teachers have very limited time and also say they are drawn to work in their own classrooms. There are important exceptions to these general observations, however. In one U.S. case study school, teachers did meet every day, and the schedule was arranged to maximize teacher collaboration.

Authentic collegiality depends not only on policies and space but also on assumptions about teaching and the work of teachers. This is suggested in one way by a German teacher who said, "I do not want to open myself to other teachers because they could use my openness to talk about me in a bad way" (Milotich, 1996, p. 352). In another way it is suggested by the expectations for teachers in Japan. There, teachers are encouraged to engage with one another as colleagues and resources. In Germany, Japan, and the United States alike, schools in which teachers were able to see themselves as having a common purpose—such as a German school devoted to educating immigrant children—were best able to support this kind of collaborative culture (Milotich, 1996, p. 353).

It is important to remember, however, that the TIMSS data on teacher collegiality are not clear cut. Teachers in some high-achieving countries claim to meet very frequently (81 percent of Japanese students at the fourth-grade level are taught by teachers who meet at least once each week), while others report infrequent meetings (in Hong Kong, another high achiever, 81 percent of students in the upper grade of population 2 are taught by teachers who report meeting no more than once a month; see Tables 5-2a and 5-2b earlier in this chapter).

The Continuum from Professionals to Skilled Workers

Teachers are members of a professional community that, by definition, assumes lifelong learning as a goal. However, they also are hired as skilled workers who are presumed to be prepared and ready to teach.

Schools vary in how they balance these dual assumptions. As described in previous sections, some schools treat teachers as members of a profession through the ways in which they hire them, organize their time, afford teachers control of certain aspects of their work and time, provide opportunities for continued learning, and facilitate collegial relationships among educators. Other schools construct cultures that treat teachers only as skilled workers. They provide the setting for the work of instruction but make few provisions for other dimensions of practice.

Although Japanese teachers described their profession as reasonably well respected, they worried about their situation. "Despite relatively high levels of support, training and respect, teachers were quick to wish for even more support, criticize training as too systematic, [and] bemoan the fact that sufficient training does not occur in every school and that the status of teachers cannot be taken for granted" (Kinney, 1998, p. 189). Japanese teachers said their profession is respected but not as much as it was in the past.

German teachers, by contrast, complained that they were stigmatized as part-time workers. In the eye of the general public, teachers have long vacations (12 weeks in all) and afternoons off. Although German teachers structure a large portion of their work time themselves, they emphasized that, while at school, they work almost nonstop in a fast-paced, high-stress environment. They said most people do not realize how much time they spend at home preparing for classes and grading exams. "They expressed frustration with the expectations placed on teachers and disappointment with what they perceive as declining respect for their profession" (Milotich, 1996, pp. 337–338).

In addition, the material and symbolic benefits that accrue to teachers help to situate them on a continuum from professional to skilled worker. For example, competition for entry into the profession is an important measure of how teaching is viewed (Table 5-4). In Germany and Japan, competition is high, as evidenced by the rigor of teacher preparation and entrance examinations. Researchers on the Japanese TIMSS case study believed this competition bolstered the status of teaching, which they described as "fairly well respected" (Kinney, 1998, p. 186). Competitiveness varies by field, however. In the humanities there are about 30 applicants for each position, while rates are closer to 10 to 1 in mathematics and science teaching—a phenomenon probably due to self-selection. One teacher explained that competition to become a mathematics teacher is less fierce than to become a teacher of other subjects simply because the mathematics coursework is so demanding: "Those who are just so-so at math won't make it" (Kinney, 1998, p. 203).

In economic terms, teaching in Japan compares favorably with other occupations (Kinney, 1998, p. 188). Because of the importance accorded teaching at all levels of education, the salaries of public school teachers are not far below those of university professors (Stevenson and Nerison-Low, 1997, p. 124). Salaries are based on length of service to the school district. As in many professions in Japan, the basic year-long salary for teachers is supplemented by bonuses equivalent to up to

TABLE 5-4 Factors Indicating Desirability of Teaching Profession

|

|

Japan |

Germany |

United States |

|

Competing to enter teaching profession |

High |

High |

Varies by location |

|

Salary, bonus, benefits |

Above average |

Above average |

Varies by location |

|

Occupational status |

Above average |

Civil servant: varies by type of school |

Average to low |

|

Source: Stevenson and Nerison-Low, 1997, p. 123. |

|||

five month's salary and allowances for certain personal and professional expenses.

In contrast, U.S. teachers earn less on average than professionals in other fields with comparable years of university and graduate education. According to the 1997 survey and analysis of salary trends conducted by the American Federation of Teachers (available at http://www.aff.org/research/salary/home.htm), the 1996–97 average teacher salary was $38,436. Salaries in other white-collar occupations tended to be higher, from 74 percent more for attorneys to 10 percent more for accountants. This pay differential has contributed to a shortage of mathematics and science teachers in some parts of the country, which has forced schools to rely on teaching out of field and teachers who have gone through alternative certification tracks.

German teachers are compensated according to a national civil service pay scale (Milotich, 1996, p. 340). Their salaries—ranging from about $35,000 to $40,000—depend on the type of school or level at which they teach, as well as their years of service, marital status, and family size.

Employment benefits also differ among Germany, Japan, and the United States (Table 5-5). All teachers in the three countries receive medical, retirement, and vacation benefits, although the specifics vary. In addition, teachers in Japan are "eligible as civil servants for extra monetary allowances for dependents, financial adjustments (such as cost of living), housing, transportation, assignments to outlying areas, administrative positions, periodic costs (such as those incurred when traveling with sports teams), and diligent service" (Kinney, 1998, p. 188). Japanese national and local education authorities also offer teachers travel and study options.

The German case study suggests that job security is one benefit associated with teaching in that country. As civil servants, German teachers cannot be laid off.

STUDENT ATTITUDES

Internationally, students tend to share positive attitudes toward math and science. Most U.S. fourth and eighth graders report that they like both mathematics and science, though more fourth graders liked these subjects than eighth graders. However, the decline in

TABLE 5-5 Teachers' Compensation Packages

|

Japan |

Germany |

United States |

|

National pay scale |

Civil servant pay scale in former West German states; separate pay scale for teachers in former East German states |

District pay scales |

|

Salary based on level of school, type of position, level of responsibility, years of teaching experience |

Civil servant pay scale based on years of education required; pay increases with years of service |

Determined by degree attained, years of teaching experience, and location |

|

|

|

Merit-based raises adopted in some districts |

|

Bonuses twice a year |

Christmas bonus |

None |

|

Allowance for family composition, remote area, special services, vocational education, end of year, and extreme climate |

Allowance for households, based on marital status and family size, usually 30 to 35% of base salary |

None |

|

Benefits: medical, retirement, vacation, housing, investment plan, low-interest loans |

Benefits: medical, retirement, vacation, dental |

Benefits: medical, retirement, vacation, dental, life insurance |

|

Source: Stevenson and Nerison-Low, 1997, p. 115. |

||

|

QUESTIONS RELATED TO STUDENT ATTITUDES

|

affection for mathematics and science from fourth to eighth grade in the United States is typical internationally (U.S. Department of Education, bo, p. 50).

Where differences in student attitudes emerge among countries, TIMSS findings have interesting implications for student achievement. Most notably, while most students in most countries think they do well in mathematics and science, students in some of the highest-performing countries recorded markedly lower perceptions of their own performance. For example, in almost all TIMSS countries, most population 2 students said they did well in mathematics, but three of the four countries in which this was not true—Hong Kong, Japan,

and Korea—were among the highest-performing countries (Beaton et al., 1996a, p. 117). Similarly, in all countries except those three, most students said they did well in either integrated science or science as a whole, yet Japan and Korea were among the highest-performing countries in science (Beaton, 1996a, p. 111). These findings suggest that students in high-performing countries may work especially hard to meet perceived shortcomings.

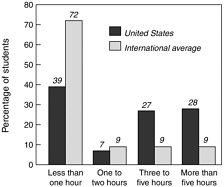

Data from TIMSS indicate that U.S. students also believe that hard work is important in learning mathematics and science. Students expressed this belief at the same time, however, that they devoted relatively little out-of-class time to studying and more to job-related activities (National Research Council, 1998; Schmidt et al., 1999, pp. 109–110). For example, U.S. students in population 3 work significantly more than their peers internationally (Figure 5-1).

Figure 5-1 U.S. twelfth-grade students' reports on number of hours on a normal school day spent working at a paid job in comparison with the international average.

Source: U.S. Department of Education, 1998, p. 68.