4

Information Systems for Monitoring Quality

Information based on valid, reliable, and timely data about the care provided, the recipients of care, the facilities, and the caregivers providing care is fundamental to all strategies for monitoring and improving the quality of long-term care. Such information is of interest to many constituencies, including consumers, caregivers, provider organizations, managers, regulators, purchasers, and researchers. Consumers and their advocates want information to guide the selection of care providers, monitor current care, inform efforts to encourage and promote system-wide improvements in long-term care, and work with their providers to improve quality of care. Providers want such information to target their efforts toward improving care processes and outcomes. Regulators need this information to identify quality problems, target monitoring and enforcement processes, and confirm corrective actions. Purchasers of care, such as Medicare, Medicaid, or even managed care plans, might use this information to decide who should care for their beneficiaries or subscribers.

Over the last decade, the long-term care field has moved to develop and implement uniform, universally required individual level data collection systems that can form the basis for measures of quality performance. The 1986 Institute of Medicine report recommended a uniform minimum data set for nursing home resident assessment. However, such a recommendation would never have been made without a general consensus that nursing home quality was poor and that the provider community was neither willing nor able to make the changes needed to improve the quality of care without specific direction. As is described below, the

nursing home Resident Assessment Instrument was introduced early in 1990 and has become the basis for various payment and quality monitoring initiatives. The perceived policy “success” of the nursing home system prompted the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) to mandate the introduction of a measurement system for Medicare in order to reimburse for home health care. A number of states have had long-standing patient assessment systems of their own for users of assisted living facilities, senior centers, and non-Medicare home care providers. Numerous states are now struggling with the adoption of common, clinically relevant data elements pertinent to all long-term care clients that are applicable across all provider settings in order to facilitate and track Medicaid-managed care reforms tentatively being applied to the long-term care population.

The notion that information about care recipients and care providers, all linked into a single database, can be used to monitor and improve care is consistent with the extensive literature emanating from the continuous quality improvement field. The same data that make it possible for providers to identify current care practices that contribute to undesirable patient outcomes, can also be used by regulators to identify providers that may manifest care practices associated with problematic outcomes. Presumably these data could be used also to classify providers as “poor performers,” which information then could be made available to the public.

This chapter discusses the current state of the major information systems in long-term care, their implementation status, their reliability and validity, and their application for clinical assessment, quality monitoring, and reimbursement. The discussion primarily focuses on the federal systems that provide basic information on monitoring compliance with regulations and on the quality of long-term care offered by nursing homes and home health agencies. These are the On-line Survey and Certification Assessment Reporting (OSCAR) System for nursing homes and home health, the minimum data set (MDS) for the Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) for nursing homes used in developing quality indicators, and the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) for home health care. The chapter then briefly describes the need to improve these existing information systems in light of their extensive use for policy and quality monitoring; state assessment systems for home and community-based service; and the measurement and implementation issues involved in efforts to extend their use to other long-term care settings and to include consumer perspectives in assessments of the quality of life and satisfaction with care. Because most existing data systems in long-term care have been developed primarily for adults, and the elderly in particular, some of the special challenges in assessing children's care also are discussed.

ON-LINE SURVEY AND CERTIFICATION ASSESSMENT REPORTING SYSTEM

The OSCAR system is a computerized national database for long-term care facilities used for maintaining and retrieving survey and certification data for providers and suppliers that are approved to participate in the Medicare or Medicaid programs. OSCAR also is used as a quality assessment tool. The database contains information entered by state survey agencies or HCFA regional offices during periodic inspections for certification of health care facilities.

OSCAR provides information on how well a nursing home has met the regulations in the past and provides on-site surveyors with background information on past performance. As such, it serves as a quality assessment tool. It has five major components of interest: facility characteristics, resident characteristics, staffing, survey deficiencies including scope and severity, and complaints (see Chapter 5 for more details). The data are collected and updated on a regular basis by state licensing and certification agencies under contract with HCFA to conduct Medicare and Medicaid certification surveys. At the time of state surveys, nursing facilities complete information on their facility characteristics, resident characteristics, and staffing on HCFA forms. Staffing data include the number of full-time equivalent positions in the facility—employees or contract workers —over the previous 14 days. The deficiency data are based on the findings from the state survey when a state surveyor, using protocols specified by HCFA, judges that a facility has not met a regulatory standard. Deficiencies are classified by scope and severity. These data are entered by state offices into the OSCAR database. It should be noted that there is often a lag (on average, 5–6 months) between the facility 's survey and when the data can be accessed and aggregated for analysis. The system retains up to a four-inspections history of deficiency information and resident census data for the same period.

Each facility must have an initial survey to verify compliance with all federal regulatory requirements in order to be certified for Medicare or Medicaid. Once certified, nursing homes are resurveyed annually in order to continue certification. States are required to survey each facility no less often than every 15 months, and the state average is about every 12 months. Follow-up surveys may be conducted to ensure that facilities correct identified deficiencies. In addition, surveys are required when there are substantial changes in a facility's organization and management. Finally, surveys may be conducted to follow up a complaint that alleges substandard care.

OSCAR facility data, as recorded, include information on: type of certification, bed size, occupancy, the name and address of the corpora-

tion, ownership type (profit, nonprofit, or government), whether the facility is part of a chain, percent of residents on Medicare and Medicaid, information on special units for those with Alzheimer 's disease, and other information. Information on the number of residents in the facility with particular problems (e.g., pressure sores, incontinence) or receiving special services (e.g., rehabilitation, tube feedings) on the day of the survey is also included. Staffing data reported includes the number of full-time equivalent positions in the facility —employees or contract workers—over the previous 14 days.

Resident characteristics also are reported by nursing facilities. These include activities of daily living (ADLs), restraints, incontinence, psychological problems, and other special care needs of residents. Nurse staffing (registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and nursing assistants) hours per resident are reported by facilities for a two-week period prior to when the survey is conducted. These data are the only major source of information for all facilities on staffing levels. Finally, data on facility deficiencies are based on state surveyor evaluations of the process and outcomes of care in the facilities. Deficiencies are given on resident rights, admission, transfer and discharge rights, resident behavior and facility practices, quality of life, resident assessment, quality of care, nursing services, dietary services, physician services, rehabilitation services, dental services, pharmacy services, infection control, physical environment, and administration. OSCAR does not include claims, use, or expenditure data.

The instructions for completing the various components of the OSCAR data are included in HCFA's State Operations Manual, which guides the survey protocol to be followed by state officials for inspecting nursing homes during the annual certification and re-certification visits. Much of the information on facility and resident characteristics is initially compiled by facilities and then checked by surveyors against medical records, staffing records, and resident observation (Harrington and Carrillo, 2000).

OSCAR information can be used by federal and state survey agencies to examine a facility's survey results and patterns of deficiencies over time. The data can also be used to provide information to consumers. As part of President Clinton's nursing home initiative in 1998, HCFA has made much of the OSCAR data available to the public through its Medicare nursing-home-compare website, which presents OSCAR data 1 on every nursing home in the United States (HCFA, 1998a). In addition, several commercial firms have Internet-based systems that use OSCAR data in ranking nursing homes on the basis of their designated deficien-

|

1 |

The site includes selected facility characteristics, resident characteristics, and deficiencies. HCFA is in the process of adding more OSCAR information to the website. |

cies, as well as on the basis of the compatibility of the facility with the needs and preferences of residents. As part of a project for the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, researchers have developed a prototype consumer information system based on OSCAR data.

HCFA periodically modifies the OSCAR system to include new data elements or provide new instructions to make the assembly of the OSCAR information consistent with other sources, such as the MDS. HCFA is planning on another major revision of OSCAR in the near future in order to accommodate new types of structural and process information that will better characterize the clinical resources available in and to the nursing home.

Limitations of OSCAR

There are several sources of concern about the limitations of OSCAR data, some of which emanate from a lack of explicit audit procedures. For example, the data on facility characteristics and staffing are not routinely audited by state surveyors to ensure the accuracy of the data. Data on facility ownership are not detailed enough to identify the owners of facilities for tracking and enforcement purposes, and information on changes in administrative leadership of facilities, although required by HCFA and reported to states, are not built into OSCAR.

OSCAR data about residents are based on aggregated resident characteristics summarizing the resident census taken by the provider before submission to the surveyors. Such data make it impossible to disaggregate the information to look at subsets of residents within a facility. With increased segmentation and specialization in the nursing home industry, a simple count of the number of residents with particular characteristics is increasingly misleading. For example, the severity of a facility 's casemix is reflected in indicators such as the proportion of residents who are incontinent or are being tube-fed on the day of the survey. Interpretation of these data could be difficult without individual-level data that can be used to differentiate, at a particular point in time, between residents who acquired these characteristics while in the facility and residents who entered the facility with these characteristics. Moreover, the data collected on resident characteristics are not audited by state surveyors.

OSCAR data on staffing also are not audited by state surveyors, and analyses of staff-to-resident ratios show some facilities reporting data that are likely to be inaccurate (Harrington et al., 1998a). One reason for this may be that the instructions for completing the information are not easy to understand. Also, because nursing homes can often predict when surveys will be conducted and because the surveys report only the previous 14 days of staffing, facilities can “staff-up” before the inspection. Thus the

usual staffing levels for a facility may differ from those reported during inspection, making it difficult to use OSCAR data to identify quality problems that may be related to staffing levels. Staffing data would be more useful if they covered longer time periods (e.g., a quarter) and were audited by conducting a check of personnel records. OSCAR data do not include information on staff turnover or continuity (length of employment) or on the education and training of staff. This information would be valuable in monitoring facilities with high turnover and poor staff continuity.

The OSCAR data on deficiencies are considered to be valid in part because deficiencies are generally scrutinized carefully and often contested by nursing facilities. However, variability within and between states in the consistency of adherence to survey “interpretive guidelines” in deficiency citations is problematic, at least on the basis of interstate variability in the number and types of deficiencies cited in the survey process (see Chapter 5 for further discussion) (Harrington and Carrillo, 1999).

Finally, the OSCAR system does not include cost data. Cost data are currently available only from the annual Medicare cost reports filed by nursing homes with the fiscal intermediaries (contractors that pay Medicare claims) and from the annual cost reports filed with state Medicaid agencies. The lack of national financial data and of standards for reporting these data impedes research on the relationship between the cost and the quality of nursing home services.

An additional source of information about long-term care in nursing homes is complaint data. OSCAR also includes data from surveys conducted as a part of complaint investigations. The General Accounting Office (GAO) (1999c) and HCFA have reported that some states have not been conducting systematic investigations of nursing home complaints and have not been entering complaint data into the OSCAR system. HCFA is working to improve the complaint investigation and reporting system.

THE RESIDENT ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENT AND THE MINIMUM DATA SET FOR NURSING HOMES

An important requirement of the nursing home reforms in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA 87) was the development of uniform resident assessment for all nursing home residents. The resident assessment instrument (RAI) includes a set of core assessment items, known as the Minimum Data Set (MDS) for assessment and care screening and more detailed Resident Assessment Protocols (RAP) in 18 areas that represent common problem areas or risk factors for nursing home residents. Its primary use is clinical, to assess the functional, cognitive,

and affective levels of residents on admission to the nursing home, at least annually thereafter and on any significant change in status and to develop individualized, restorative care plans. The RAI was designed as a structured approach to assessing a nursing home resident 's needs for care and treatment in preparation for the development of a plan of care. The assessor is directed to examine certain issues or ask about certain aspects of the resident's condition; the instrument was designed to be completed by a trained nurse and not as an interview or survey to be completed by the resident.

Based on the advice and consultation from relevant professional and provider groups, researchers, and state and federal regulators, the MDS was created, tested, modified, retested, and then implemented by the end of 1990 in all Medicare- and Medicaid-certified nursing homes in the United States. The final version has 15 domains: cognitive patterns, communication and hearing patterns, vision patterns, physical functioning and structural problems, continence, psychosocial well-being, mood and behavior patterns, activity pursuit patterns, disease diagnoses, health conditions, nutritional status, oral and dental status, skin condition, medication use, and special treatments and procedures (Morris et al, 1990).

Extensive testing and analysis of the MDS has been undertaken to examine the reliability, validity, and sensitivity of individual MDS data elements, as well as composite scales constructed from these data elements. By and large, items characterizing patient's physical functioning were found to be reliable, valid, and sensitive to change. However, measures of depression and other psychosocial indicators have been shown to be less reliable and valid. For example, interrater reliability levels were significantly lower for residents with serious cognitive impairment, indicating the importance of being able to speak with residents (Phillips et al., 1993b).

Design of a revised instrument was initiated almost immediately after implementation of the initial version to account for the rapidly changing mix of people entering nursing homes and to make improvements based upon feedback from the evaluation on both clinical and empirical sources. Version 2.0 of the RAI's MDS was introduced in January of 1996 in most nursing homes across the country. Since June 1998, all nursing homes are required to transmit the MDS information electronically to HCFA on a quarterly basis.

The reliability of both the modified items and new items in MDS version 2.0 were tested and found to out-perform the previous version (Morris et al., 1997). A 4-year evaluation was conducted to assess RAI's impact on the residents' functional, cognitive status, and psychosocial well-being. A quasi-experimental design was used involving the collection of longitudinal data on two cohorts of nursing home residents. Two-

thousand nursing home residents in a random sample of 267 facilities located in 10 geographic areas were assessed during the pre-RAI period. In the post-RAI period, 2,000 new residents in 254 of the same facilities were assessed. The researchers found that implementation of the RAI was associated with significant improvements in the quality of care in nursing homes by reducing overall rates of decline in important areas of resident function, in a variety of measures of processes of care, and in reduced hospitalization (Hawes et al., 1997a,b; Morris et al., 1997; Phillips et al., 1997).

HCFA initiated a multi-state Nursing Home Casemix and Quality Demonstration project using the MDS and other measures. The data from this project were used to develop the Resource Utilization Groups-III (RUGS-III) to determine the amount of resources needed for 44 different homogenous types of residents. They are now being used to classify residents in terms of the intensity of nursing and other services needed for the purpose of paying facilities differentially based upon the mix of residents in their home. A strong positive relationship was found between resident characteristics (casemix) and nurse staffing time needed to provide care (Fries et al., 1994). The RUGS-III system now forms the basis for the newly implemented prospective payment system for Medicare Skilled Nursing Facility admissions mandated under the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.

Concerns About Use of the MDS

The rationale for using the MDS to obtain data related to the quality of care is that the information collected is integral to the care process, forming the basis for the individualized care plan. Furthermore, state regulators are supposed to check the internal consistency of the MDS data in a resident's chart and their conformance to the picture of the resident as described in the medical chart and in nursing notes. A major assumption made by those who propose using these types of clinical data for quality monitoring is that, since the data have utility for the care process, facilities and nursing staff have a vested interest in their accuracy. In 1998, HCFA awarded a contract specifically to examine the accuracy of MDS data. An earlier study had found that the accuracy of 23 data items in patients' records increased significantly with the advent of the MDS (Hawes et al., 1997b).

The committee notes that such studies are not necessarily conducted under “real world” circumstances, and the test environment does not always match that for routine use of the instrument. Thus, these trials demonstrate the reliability of the MDS items themselves when used by trained staff, but may not necessarily reflect how the data are assembled

in the average facility, raising the issue whether nursing homes have adequate staff with sufficient training and knowledge to perform accurate assessments.

Some concern has been expressed by providers about the institutional burden that use of the MDS imposes in terms of staff time, skills, and energy required. Although the committee heard from some providers that the burden was disproportionate to the value, most providers agreed that the MDS was useful in both resident care planning and internal quality improvement efforts, especially as computerized access to the assessment and related data became more available (AAHSA, 1998; ACHCA, 1998).

As stated above, the MDS is used to classify residents into 44 different RUGS for purposes of Medicare prospective payment. The new prospective payment system was developed using the amount of time needed to provide care to the different RUGS. Thus Medicare's higher rates are paid for residents in higher RUGS groups. One can speculate that as with the effect of the hospital prospective payment system on coding practices for hospital discharge diagnoses, higher payment rates for care of more seriously ill nursing home residents potentially could create incentives for nursing homes to “upcode” that might distort the MDS data. HCFA is conscious of this possibility and is currently pursuing the development of automated programs to monitor the accuracy and consistency of MDS data.

Development and Use of MDS Quality Indicators

Using data from the MDS, Zimmerman and colleagues (1995) developed quality indicators (QIs) as a part of the national Nursing Home Casemix and Quality Demonstration Resident Status Measurement study funded by HCFA. The QIs are designed to monitor the changes in residents and the outcomes of care (Zimmerman et al., 1995) for use by state surveyors to identify problem areas in individual resident characteristics and in services within facilities. Twenty-four QIs have been developed using the revised MDS (version 2.0), including accidents, behavioral and emotional problems, cognitive problems, incontinence, psychotropic drugs, decubitus ulcers, physical restraints, weight problems, and infections (Zimmerman et al., 1995). The QIs were designed to identify residents with the potential for receiving poor quality or high quality of care based on their prevalence rates in comparison nursing facilities. Some of the QIs were adjusted for those facilities with more high-risk residents; other QIs were based on a general standard and not risk adjusted by design. These measures were found to have high validity (Karon et al., 1999).

HCFA is using the QIs to bolster and systematize the quality monitoring process. QIs for individual facilities are now used by state surveyors in the survey process. This allows the observed rates of QIs in a facility to be contrasted to a statewide rate. These reports are provided to both the state surveyors and the facility being inspected. In addition, the software generates a listing of the individual facility residents who met the criteria for possible quality-of-care problems. This roster of residents is being used as the starting point for the selection of records for review during the inspection to determine whether a quality-of-care problem can be confirmed. The QIs have also been aggregated to create a set of facility-level quality indicators that characterize the quality of care in the nursing homes in which those individuals live (Zimmerman et al., 1995).

HCFA is currently funding a contract to identify those QIs that need additional validation testing and modification and to develop new sets of quality indicators for special nursing home populations, such as those receiving post-acute care over a short-term period and residents receiving palliative care. In addition, HCFA has commissioned the development of a new set of facility performance measures that will supplement MDS data with data from residents and their families that capture their values, preferences, and satisfaction with the care received.

These facility-level quality indicators can be valuable for targeting internal quality improvement activities by nursing facilities. These data could also be used as indicators of quality to guide decisions by purchasers or consumers. In spite of these concerns about the use of resident assessment information (originally designed to improve care planning) for policy and regulatory purposes, the committee believes that the general notion of using information about the performance of a facility should be encouraged. HCFA should continue to test and validate the systems of quality indicators now being planned and implemented for nursing facilities.

In the short term, HCFA plans to introduce quality indicator software into states' existing systems for uploading computerized MDS data from all facilities in the state. The plan calls for the software to generate quality indicator reports describing the proportion of the residents of the facility that, based on the most recent MDS assessment, meet criteria for potential quality problems ranging from having pressure ulcers, to taking anti-psychotic medications in the absence of specific diagnoses, to declining in an area of activities of daily living. The observed rate of each facility will be contrasted to some “benchmark” that has yet to be determined. These reports will be generated both for the surveyors scheduled to inspect a facility as well as the facility itself.

HCFA is moving toward a more information-intensive approach as an outgrowth of the short-term plans mentioned above. It has awarded

four major contracts to advance past work on quality indicators in the nursing home field. All are designed to further HCFA's goal of using the MDS, in both aggregated and individual-level format to bolster and systematize the quality monitoring process. HCFA's vision of this process is that the MDS data constitute the basis for directing survey and certification activities, setting payment levels, and developing information about the quality of long-term care providers to consumers and purchasers.

OUTCOME AND ASSESSMENT INFORMATION SET FOR HOME HEALTH CARE

The perceived utility of the nursing home resident assessment system, particularly its use in developing a Medicare casemix reimbursement method based on resident data, has prompted HCFA to mandate the introduction of a similar data system for Medicare-certified home health care agencies. The Outcome and ASsessment Information Set (OASIS) is a group of data elements that represent core items of a comprehensive assessment of an adult home care patient and form the basis for measuring patient outcomes for purposes of outcome-based quality improvement. OASIS is a key component of Medicare's partnership with the home health care industry to foster and monitor improved home health care outcomes and is proposed to be an integral part of the revised conditions of participation for Medicare certified home health agencies. HCFA regulations require that as of mid-1999, all certified home health agencies start systematically using OASIS to measure the functional status and medical conditions of all eligible Medicare beneficiaries receiving home health care. The state agencies have the overall responsibility for collecting OASIS data in accordance with HCFA specifications.

OASIS was developed by researchers at the University of Colorado (Shaughnessy et al., 1997a,1998b) over a 15-year period on the basis of work funded by HCFA and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. It was designed primarily to produce data that could be used in assessing the outcomes of care provided in the home setting, not as a comprehensive assessment instrument for use in planning patient care, although it does represent core items for an assessment of an adult home health care patient. The objective was to produce a data collection and quality improvement system that would be of primary utility to the home health care industry and the patients it serves. A secondary purpose has been to meet the needs of payers, regulators, and government.

The outcomes-based quality assessment approach represented by OASIS assumes that the quality of care provided by a home health agency can be evaluated on the basis of the outcomes its clients experience relative to similar persons served by other agencies or by the same agency

over time (Shaughnessy et al., 1994a,b, 1998a). OASIS includes 89 items covering demographics and patient history, living arrangements, supportive assistance, sensory status, integumentary (skin) status, respiratory status, elimination status, neuro/emotional/behavioral status, activities of daily living, medications, equipment management, and other information collected at inpatient facility admission or agency discharge. Most OASIS data items are collected at the start of care and every 60 days thereafter until and including time of discharge (Shaughnessy et al., 1997a).

During the development of OASIS, several different reports were designed, tested, and refined by having home health agencies collect, computerize, and transmit OASIS data, and then use the resulting reports for clinical and administrative decision making, and, most importantly, quality improvement (Shaughnessy et al., 1998a). The three principal reports are (1) outcomes reports, (2) adverse event reports, and (3) casemix reports. The outcomes reports aggregate patient-level data to produce agency-level performance data on more than 40 outcomes, such as changes in ambulation or locomotion, speech or language, status of surgical wounds, and acute-care hospitalizations. Agency performance is compared to a national reference or benchmark sample and to the agency's own past performance. Risk-adjusted measures are included. The outcomes reports are typically produced annually to have an adequate number of cases for statistically meaningful results. Adverse event reports focus on low-frequency outcomes that may point to problem areas requiring attention. Casemix reports describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients admitted to an agency during the previous year.

OASIS was tested extensively for its soundness as a measurement tool and its usefulness in practice. Reliability and validity testing was undertaken with a view toward enhancing the precision and utility of the OASIS data set and the outcomes measures. For inter-rater reliability, for example, studies using either simultaneous or sequential ratings have demonstrated the reliability of the components of the OASIS instrument (Shaughnessy et al., 1994b, 1997a). In a recent study, with nurses independently visiting a patient's home on successive days, the reliability for core data items was 0.62 or above, with most items having reliability coefficients above 0.75 (Shaughnessy et al., 1997b).

Because it is likely that client outcomes are associated with clients ' clinical condition on admission or their history of medical problems, the OASIS designers created reasonably homogeneous “casemix” groups of clients thought to be “at-risk” of experiencing a given outcome (whether positively or negatively defined). The developers of OASIS created 25 Quality Indicator Groups that encompass acute medical problems such as acute pulmonary conditions, as well as chronic conditions and impair-

ments (not just medical diagnoses). Some end result outcome measures apply to all QI groups while others are specific to a particular group and the likely therapeutic goals that home health staff would set for these patients. Agencies can be compared on the percentage of the clients in a given QI group that improved, stabilized, or deteriorated between enrollment and the designated follow-up period.

OASIS has been adapted to meet the needs of various audiences, including home health care patients, Medicare beneficiaries, Medicaid clients, home health care clinicians, referring physicians, home health care administrators and managers, agencies that provide home health care, Medicare and other payers, Medicare Survey and Certification agencies, voluntary accreditation agencies, and the research community, policy makers, and consumers. Some of the applications of OASIS data that serve these various groups include the following: evaluating outcomes of home health care at the agency level; assessing quality of care across multiple provider settings; adjusting prospective payment rates for casemix differences; determining the impacts of payment and regulatory policies on home health care casemix and outcomes; detecting discrimination and access barriers to home health care; increasing efficiencies and effectiveness of Medicare and Medicaid survey and certification; facilitating voluntary accreditation; informing consumers; and marketing successful home health care programs. OASIS is being studied for use in Medicare prospective payment systems. For the National Prospective Payment Demonstration (Goldberg et al., 1998), 91 home health agencies in California, Texas, Florida, Illinois, and Massachusetts collected a subset of OASIS data for purposes of evaluating the impact of prospective payment on outcomes, and to selectively monitor and assure the quality of care in the context of the demonstration.

Despite its broad applicability to both Medicare and Medicaid populations, OASIS has developed no application for younger populations including children and young adults in home health care, or working age adults in various long-term care and personal assistance arrangements. Thus, the ability of OASIS to provide meaningful information regarding these populations is untested and unknown. Indeed, no current measurement systems provide useful data about quality of care for these populations.

CHALLENGES IN USING ASSESSMENT DATA

Several technical and methodological challenges exist in using individual-level assessment data successfully for policy purposes such as reimbursement and quality monitoring. Many relevant events of interest are relatively rare, particularly for individual nursing homes or home

health agencies. For example, the number of individuals with incidence of pressure ulcers served by a facility or agency might easily vary quarterly from none to three, even in an excellent facility. This small number makes it difficult to calculate reliable estimates of the incidence rates of such events for a standard observation interval. However, as discussed in the previous chapter, prevalence data can be used in such cases to eliminate small numbers problems.

QI values are expected to change over time, but to be a good indicator of quality, they should be reasonably stable over “short” periods. In a study of 512 nursing facilities from two states, Kansas and South Dakota, Karon and colleagues (1999) examined the stability of QIs over each of two 3-month periods and one 6-month period. Results of the study indicated high levels of stability for most QIs. The authors concluded that QIs are reasonably stable over “short” periods of time. All QIs are not of the same type and depending on the characteristics and definition of each QI, the stability has to be examined with caution. Another study using residentlevel data from 500 nursing facilities in Massachusetts examined the stability over time. As would be expected, they found only moderate to poor correlations over time within several quality indicators (Porell and Caro, 1998). This was particularly true for outcomes like change in ADL functioning simply because change rates varied over time, unlike the prevalence of restraint use, which was more stable.

Another concern is the accuracy and completeness with which data are collected and the uniformity of data reporting over time and across providers. This is a concern in most large data collection programs. One way to address this problem is to provide detailed guidance on the data collection and reporting processes. Evidence from the use of individual clinical assessment instruments indicates that explicit instructions and training in how to assess patients or clients improve the reliability of clinical data (Bernabei et al., 1997). Federal government agencies, such as the National Center for Health Statistics in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in collaboration with states have spent decades refining uniformity of data elements reported in state vital records. The importance of similar collaborative efforts for long-term care quality measurement is clear.

An issue that must be considered in using assessment data on long-term care across settings is the effect of casemix differences among various groups of long-term care users. Residents of nursing homes are generally more disabled than people using home health care services, and nursing home residents may, therefore, be at greater risk for certain adverse health outcomes regardless of the quality of care they receive. Even within a single care setting, the populations served by some providers may have more serious health problems than those served by other providers.

Statistical “risk adjustment” techniques are used to help compensate for casemix differences, and the need for such adjustments has been shown in various studies of long-term care outcomes (e.g., Arling et al., 1997; Ooi et al., 1999).2

There are limits to what risk adjustment can do. As in the case of acute care hospitals, in some markets there are relatively few long-term care providers of a given type and these tend to be associated with certain specialization areas (e.g., post-acute rehabilitation services or dementia care). Indeed, research evidence shows that in the most competitive markets, providers seek to differentiate themselves precisely by specializing (Banaszak-Holl et al., 1996). Such specialization results in different types of patients being referred to different providers. The more this differentiation occurs, the less risk adjustment can account for very substantial differences in outcomes.

As indicated earlier, however, despite these problems it is essential that continued refinement and evaluation of these data should continue, keeping in focus the concerns discussed above.

ASSESSMENT AND QUALITY MONITORING INSTRUMENTS FOR OTHER SETTINGS

Minimum Data Set for Residential Care

A variety of residential facilities offer room, board, and supervision to frail individuals without certification by the Medicaid or Medicare programs. Regulated entirely by states under an often confusing array of labels, these facilities vary widely in terms of their staffing levels and staff training, and the impairment levels and medical and nursing care needs of the population they serve (Mor et al., 1986; Spore et al., 1996). Several states have developed assessment systems for use in such residential care settings drawing on the RAI and MDS for nursing homes for assessing key functional status items. Other items, however, were developed specific to the population monitored.

The instruments developed by Maine and North Carolina are reviewed briefly here. Both states have tested their instruments in real-world settings and are at the point of introducing them statewide. In Maine, the RAI for residential care facilities was designed to provide a core set of

|

2 |

Risk adjustment here refers to the process of statistically compensating for differences in factors that influence outcomes apart from care (e.g., age, functional abilities, cognitive impairments, emotional impairments, presence of a surgical wound, shortness of breath, and various other physiologic conditions) when comparing the outcomes of one provider or care setting with others. |

elements for assessing high risk individuals, improving and assuring quality, developing plans of care, and adjusting payment rates for levels of need (Mollica, 1998). North Carolina developed an RAI for Domiciliary Care, to be used in conjunction with the physician's assessment or physician's orders, to create a plan of care and to provide information to facility staff about a resident's functioning levels and needs for assistance (Hawes et al., 1995b). This instrument was tested in 28 facilities where trained facility staff completed the instrument for 105 residents who were then independently assessed by registered nurses. Items on physical functioning achieved adequate reliability, but the items on instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) and some of the behavior and mood items were found to have relatively low reliability in this type of setting.

State Assessment Systems for Home and Community-Based Service

Many states have developed assessment systems to guide their HCBS programs. Some states have been using, improving, and modifying such tools for 20–30 years. However, most states use these instruments only for Medicaid reimbursed clients. In some states, information systems differ by target populations or programs, but other states are consolidating the instruments across programs and target populations (Kane, 2000). For example, Florida (Kane et al., 1991b), Kansas (Mollica et al., 1994) and to a lesser extent, Vermont (Reinardy et al., 1994) have consolidated assessment forms and procedures from different programs. The Florida effort also tested the reliability, sensitivity, and specificity of their new procedures and instrument.

These assessments are for care managers to: determine initial and continuing eligibility for the HCBS program and, if applicable, the levels of services and benefits to which the consumer will be entitled; establish priorities for beneficiaries and services if availability is limited; develop and implement a care plan incorporating consumers ' needs and preferences; evaluate the effectiveness, safety, and adequacy of the individual plans; determine and improve the quality of services; and provide information describing the clients, services, outcomes, and costs of the programs, including variations on these elements.

Assessment instruments vary from state to state but typically include functional status, a summary of health status, cognitive status, affective status (especially depression), and social well-being including social and economic resources. Assessments also may include the physical environment, behavior that puts the consumers at risk, and well-being of the family caregiver. Some states assess the extent of burden on the family caregivers and the dependability of informal care providers.

Some state assessments instruments include consumers' responses in

addition to the impressions of the assessor. Not all states aggregate assessment data into a single score for selecting beneficiaries, specifying how much care to offer in the community, and deciding who should be considered for community-based services and who should receive nursing home care. Such scoring systems could be useful in assessing the reliability of care plans and appropriateness of placements. Eligibility for nursing home care also determines eligibility for Medicaid HCBS waivers which are limited for those consumers needing nursing home level of care. Reviews of these practices in all 50 states conducted in the last decade showed wide variations in how nursing-home eligibility is determined (Justice et al., 1991; O' Keefe, 1996).

Some care managers are provided decision protocols to assist them in moving from raw assessment data to care plans. For example, a project in Philadelphia identified and developed care protocols for situations that care managers commonly face, such as people with cognitive impairment who live alone, people with alcohol problems, people who fall, and people who may be victims of abuse. For each of 12 such situations suggested by the initial assessment, templates detail assessment protocols and possible action plans (Amerman et al., 1995).

Integrated Assessment Instruments for Long-Term Care

Several states have begun to restructure their long-term care assessment instruments to be more compatible with HCFA'S MDS because of the increasing proportion of the population that moves into and out of nursing homes, returning home in need of other long-term care services. Compatibility of the assessment instruments might ease the care planning process once patients are discharged into the community. Rhode Island 's Department of Elder Affairs, for example, has created a case management assessment instrument largely modeled after the MDS to allow for compatibility of assessments for individuals returning from a post-acute nursing home episode, as well as for those who will ultimately require long-term institutional placement.

Most states also have Medicaid waiver programs for home and community-based services that pay for a variety of services depending on an individual 's eligibility for Medicaid long-term care services. Assessment instruments are designed to determine an applicant's eligibility for services and then to guide the development of a plan of care and referrals to service agencies for those who are eligible. In 1996, the GAO conducted a study to better understand the role of assessment in planning home and community-based care for the elderly with disabilities. It found that all instruments record applicants' physical health but the nature of the information collected varies enormously both across and within domains

(GAO, 1996b). GAO concluded that, although all states use assessments to develop a care plan, the comprehensiveness of the assessment varies, and most states do not have standardized terms. Also, most states do not require training in the administration of the instrument despite its importance.

There is strong interest in the possibility of identifying an instrument or set of core assessment elements that is applicable to all users of long-term care regardless of setting. This interest stems in part from a growing recognition of the overlap among the characteristics of long-term care populations served in different settings, and from a desire to compare the quality and costs of care across settings. The availability of such assessment tools for long-term care settings might also help in monitoring individuals as they move from one care level or setting to another. The development of uniform definitions of various community-based services, common measures, and common sets of codes for categorizing care users' physical, cognitive, and emotional functioning would facilitate the adoption of a common language for assessing long-term care needs and the outcomes of care. Clearly, much work is needed first to examine the diversity across states of the services, service settings and service arrangements, and the infrastructure for monitoring quality; and then to develop agreements on common core data elements and uniform definitions of various community-based arrangements.

Recommendation 4.1: The committee recommends that the Department of Health and Human Services and other appropriate organizations fund scientifically sound research toward further development of quality assessment instruments that can be used appropriately across the different long-term care settings and with different population groups.

The committee notes that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has initiated some efforts in this area. For example, they have awarded a research grant to develop quality measures for residential facilities that can be used for multiple purposes.

INCORPORATING CONSUMER PERSPECTIVES IN MEASUREMENT OF QUALITY

Provision of long-term care should reflect the preferences of consumers. This suggests that data are needed about consumers' perspectives on the quality of their care, and that consumers should be included as a source of data on the quality of care. Although staff assessments are a

necessary part of these individual evaluations, especially for the portion of the long-term care population with severe cognitive impairment, staff may not be able to accurately assess such subjective conditions as pain or mood, or individuals' preferences for or satisfaction with care. Even when families serve as proxies for individuals whose impairments prevent them from responding directly, families' perceptions of satisfaction with care are not necessarily consistent with those of long-term care users themselves (Lavizzo-Mourey et al., 1992; Norton et al., 1996). Consumer and professional responses may differ at levels as basic as whether assistance is needed. Professionals may, for example, know more about the range of possible services, allowing them to identify an “unfelt need.” The training manual for the two federally mandated systems—RAI/MDS and OASIS—specifies the use of multiple sources of information for most items, including interviews with direct staff across all shifts, interviews with and observations of the resident, interviews with family members and, where relevant, review of other medical records. Although much of the work on measuring quality of life and consumer satisfaction with care has focused on primary and acute care, some efforts are being made to develop measures of consumer and family perspectives on quality of care appropriate for long-term care. For example, the major provider associations have developed data sets that they recommend to their members interested in assessing residents' and family members' satisfaction with care. Many of the larger nursing home chains have designed their own systems to measure satisfaction and might even try to use these data in the strategic planning process. Some studies have also demonstrated the feasibility of consumer assessments of in-home services (e.g., Freedman et al., 1995; Capitman et al., 1997), including reports on unmet needs for service and satisfaction with nonmedical services. The committee recognizes that quality of care is more than satisfaction. It is important, therefore, that these facilities and others do not stop with satisfaction measures but go the next step to develop and refine measures of quality of care in the assessment data sets.

Consumer Satisfaction Surveys

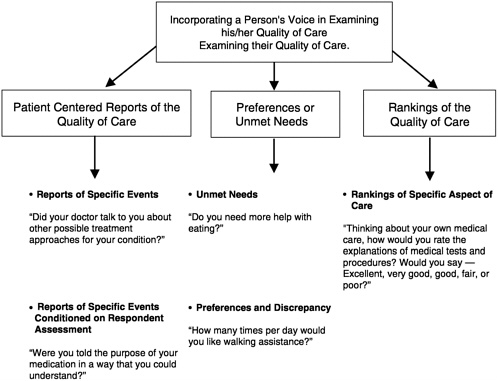

Consumer assessments of care generally address three separate dimensions: (1) consumers' experiences of care, based on reports about matters such as whether they used their call bell to seek assistance and how long the response took (Gerteis et al., 1993); (2) satisfaction with the care received; and (3) consumer preferences regarding care, elicited through questions about the aspects of care they value most highly or the kinds of assistance they would like. Responses to the last set of questions can then be compared to information on the care actually provided to

FIGURE 4.1 Proposed classification scheme for measuring a person's perspective about his/her quality of medical care.

SOURCE: Adapted from Teno, 1998.

identify possible unmet care needs. Figure 4.1 illustrates the kinds of questions that can be used to address these different dimensions of consumers' assessments of the quality of care they receive.

Some of the initial work on instruments for obtaining consumer-centered reports on medical care in acute care situations was done by Cleary and colleagues (1991). As shown in Figure 4.1, consumer-centered reports either ask a patient a factual question (e.g., Did someone speak to you about treatment for your concern?) or ask the person to judge one specific aspect of his or her medical treatment (e.g., Were you told of the purpose of your medications in a way that you could understand?). Cleary and colleagues noted that “questions were framed to be as specific as possible, to minimize the influence of confounding factors, such as the patients' expectations, personal relationship, gratitude, or response tendencies related to gender, class, and ethnicity” (Cleary et al., 1991, p. 255).

Traditionally, preference-based assessment (or indirect assessment of

satisfaction) is based on a person's reports of unmet needs or desire for additional services (Hughes et al., 1988; Manton 1988; Wolinsky and Johnson, 1991). Satisfaction measures currently used in surveys rank a particular aspect of the care on an ordered qualitative scale (e.g., from “poor” to “excellent”) or a numeric scale (e.g., from 1 to 5). The validity of measures of either satisfaction or preference may be affected by factors such as care user's reduced expectations, lack of choice, eagerness to please interviewer, unwillingness to complain, and fear of retaliation. Furthermore, preferences may be unstable. Some of these concerns about consumer assessment measures and methods are discussed below.

Issues in Collecting and Using Consumer Responses

Until recently, a consumer's perspective on the quality of health care was measured with satisfaction measures (or ranking of the quality of medical care). Such satisfaction measures can be problematic. The consumer must compare a recall or perceptions about the service provided with his or her expectation (or preference) about that service. These satisfaction measurement tools are questionable for several reasons. Many people use only the two best categories, even when medical care was less than optimal. For example, Williams and Calnan (1991) found that 95 percent of persons were satisfied with medical care, yet 38 percent reported that they had difficulty discussing personal problems with their physician and 35 percent felt that the physician did not spend enough time with them. Furthermore, the fundamental assumption is that the difference between “very good” and “excellent” is the same as the difference between “fair” and “poor.” This assumption may not hold (Fowler et al., 1996). A midpoint response may reflect a serious concern.

Another important concern is the reluctance of consumers to discuss quality of medical care, even to an anonymous interviewer over the phone (Vouri, 1987). Persons receiving long-term care services may feel especially vulnerable because they are dependent on providers for basic needs.

Reduced expectations is another area of concern. In a study of seriously ill and dying patients, Desbiens and colleagues (1996) found that the majority of patients stated that they were “very satisfied” despite pain that was extremely or moderately severe for one-half or more of the time. In another study, family members who reported patients had severe pain before they died would state that “the doctors did all that they could” (Teno et al., 2000). Yet research indicates that between 70 and 90 percent of patients' pain can be palliated with sedation (Schug et al., 1990; Portenoy, 1994; Zech et al., 1995). Lowered expectations and the lack of knowledge about possible and appropriate care severely limits the validity of consumers' responses to questionnaires that ask them to rank aspects of their

medical care. Furthermore, patient reports of quality of care may be overly based on the interpersonal skills of the provider and highly empathic skills may mask poor medical judgments. For example, caregivers with highly empathic skills may be described as “excellent” even when comparisons of their care with evidence-based practice guidelines or other criteria suggest significant concerns with the quality of that care (Callahan et al., 2000). However, the manner in which the caregiver relates to and interacts with the client is part of the quality of care. These and other important problems have been identified with satisfaction measurements (Cleary and McNeil, 1988; Rubin, 1990; Jackson and Kroenke, 1997; Rosenthal and Shannon, 1997; Kravitz, 1998; Teno, 1998).

Different strategies have been used in measuring the consumer perspective of the quality of care. Traditionally, patients' ranked or rated the quality of care. For the most part, these measures suffered skewed distribution, acquiescent response bias, and problems with reduced consumer expectations. Alternatively, preference-based assessment (or indirect assessment of satisfaction) is based on a person's reports of unmet needs or desire for additional services. But low or lowered patient expectations may limit both strategies. Furthermore, preferences may be unstable—both ethereal and ephemeral. Few studies have examined the stability or consistency of patient reports. Many researchers have questioned the appropriate use of consumer's responses in various areas of health care (Cleary and McNeil, 1988; Ware and Hays, 1988; Rubin, 1990; Aharony and Strasser, 1993; Zinn, 1994; Ross et al., 1995; Jackson and Kroenke, 1997; Rosenthal and Shannon, 1997; Kravitz, 1998).

Reliability and Validity of Responses. Several factors may influence the reliability and validity of consumers ' reports regarding their care. Social desirability and acquiescent response biases are prevalent among dependent groups, such as the institutionalized elderly, in part due to fear of repercussions from caregivers (La Monica et al., 1986). Nursing home residents reported high levels of satisfaction with care at the same time that interviewer observations and resident's open-ended comments suggest dissatisfaction and a reluctance to criticize nursing home staff (Pearson et al., 1993) and describe other quality concerns (Callahan et al., 2000). Kinney and colleagues (1994) got similar responses from consumers of HCBS services in Indiana. Because older adults in general, and women in particular, as well as individuals in poor health, tend to report higher rates of satisfaction with health care services regardless of its quality (Locker and Dunt, 1978; Ross et al., 1995), long-term-care users may report high rates of satisfaction with substandard or inconsistent levels of care. The wording and sequence of the questions can also influence responses. Among the nursing home residents studied by Simmons and Schnelle

(1999), 80 percent reported satisfaction with care (“Are you satisfied with how often someone helps you to walk?”), but in response to a separate question on care preferences (“Would you like for someone to help you to walk more often?”), only 60 percent reported that they did not want more walking assistance.

Bias in Assessments. The cognitive impairments prevalent in long-term care populations, as well as some physical impairments, make the collection and interpretation of consumer information more problematic than in some other health care areas. Many cognitively impaired people are excluded from interviews assessing care or quality of life, based on the belief that these residents cannot accurately answer questions (Kruzich et al., 1992; Aller and Van Ess Coeling, 1995).

In summary, although consumer-centered measures of the quality of care are useful, poorly developed or improperly used measures of consumer satisfaction can be misleading. Careful attention to the types of respondents included as well as “proxies” for people who are cognitively impaired may mitigate many potential measurement biases.

Even assuming that consumer assessments provide reliable and valid information, they are not necessarily a guide to quality improvement interventions. With end-of-life care, for example, significant progress has been made in identifying the medical treatment preferences of residents and families, but using this information to change medical practice and achieve care that matches preferences has proved more difficult (SUPPORT Principal Investigators, 1995; Teno et al., 1995).

MEASUREMENT CONSIDERATIONS FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG ADULTS

Measuring quality of care or outcomes of care for children and adolescents using long-term care presents particular challenges, mainly because of the complex problems of measurement in the context of children 's growth and development. Many of the indicators used to assess disability among adults are related to limitations in the ability to live independently (e.g., the need for assistance with paying bills or bathing and dressing), but such indicators are generally not suitable for children and adolescents for whom independent living is not an appropriate goal, regardless of the presence of any disabling condition. Moreover, the normal developmental process means that expectations for younger children will be quite different from those for adolescents. At the age of 2, children cannot dress themselves, usually have limited control over toileting, and have limited verbal skills, whereas the typical 15-year-old can be expected to have more skills in all of these areas.

The dynamic nature of child development affects measurement in almost all domains and has made the development of measures of children 's health status particularly difficult. For children, the domains of health status and quality of life that are particularly important include growth (mainly physical), development (mainly emotional, cognitive, and motor), and educational achievement. Indeed, for children, the important interaction with the educational sector—often affected by the demands of long-term care—has no equivalent in adult long-term care experience (Walker and Jacobs, 1985).

Another issue in measuring quality of care or outcomes for children concerns the unit of observation. Because of the dependence of children on the adults around them, especially their parents, to support their growth and development, assessments of long-term care programs should consider not only the effects on the child but also those on the child's environment. For example, parents of children with severe disabilities have a much higher rate of mental health problems, especially depression (Thyen et al., 1998; Thyen et al., 1999) and parents' poor physical or mental health negatively influences a child's development. Thus, programs aiming to improve outcomes for children with long-term care needs should address ways to strengthen families in general, rather than focusing only on the children, and assessment instruments should reflect these goals.

Current efforts to develop measurement instruments have resulted in a few general health status measures with some applicability across ages and stages of development, as well as numerous measures addressing more specific aspects of children's development (e.g., cognition or motor abilities); yet much more work will be needed to support careful assessment of the quality of long-term care for children. Current measures include: (1) the Functional Status II-R, a brief measure of general function applicable and tested across a relatively wide age range (Stein and Jessop, 1990); (2) the Child Health Questionnaire, similar to the Medical Outcomes Study SF-36 for adults, currently available in forms for children over age five (Landgraf et al., 1996); (3) the WeeFIM, a measure focused mainly on physical functioning of preschool-aged children with motor impairments (Msall et al., 1994); and (4) the Adolescent Health Status measure developed to gather adolescents' self-assessments of health status in several domains (Starfield et al., 1993). A version of this last measure applicable to younger school-age children has had extensive testing and will be released for general use shortly.

One of the health care industry standards for quality assessment, the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (also known as HEDIS), has only limited numbers of measures addressing quality of care for children and almost none addressing children with chronic conditions (Kuhlthau et al., 1998). The work of a child and adolescent health mea-

surement task force under the leadership of the National Council on Quality Assurance and the Foundation for Accountability, includes, as one component, the development of a set of quality measures to assess care for children with chronic conditions. This set has as its base a section of the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans survey designed specifically for households with children who have chronic health conditions.

CONCLUSION

This chapter has reviewed the basis for the measurement of long-term care quality relying on individual-level information to create aggregated measures characterizing provider performance. In differentiating between staff-provided data (based on codification of staff assessment information) and consumer-provided reports on the nature and quality of care provided, this chapter does not intend to imply that they are mutually exclusive. Both have strengths and weaknesses, and they should be regarded as complementary.

Despite the potential weaknesses inherent in using staff-reported data, such data are currently more readily available than consumer-reported data for both the institutional and the home health arena. A substantial amount of research is devoted to the application of these individual-level data to aggregated performance measures. To be sure, additional research is still needed to grapple with the numerous complex technical and substantive issues cited here, but these problems are being addressed and several should be substantially resolved in time.