5

Improving Quality Through External Oversight

Organizations providing long-term care are staffed with professional, paraprofessional, and support staff, and often volunteers. In the final analysis, the quality and safety of long-term care is dependent upon these individuals' actions, but their actions can be and are influenced by external forces. These forces can provide guidance, often in the form of standards that establish parameters for structures and processes, and can set expectations for outcomes. External forces can also provide incentives, financial or otherwise, for specific actions that will affect access to and safety of care, and the quality of care and life in long-term care settings.

These external forces include formal quality oversight mechanisms, purchasers of long-term care, and families. This chapter focuses on three formal oversight mechanisms:

-

regulatory oversight by federal, state, and local governments;

-

consumer advocacy programs; and

-

accreditation.

The committee recognizes that other forces—including mass media, care management and monitoring programs, and contractor standards set by purchasers—also influence provider behavior. The approaches of regulatory oversight, advocacy, and accreditation are somewhat different. Their relative strengths and weaknesses may make them differentially suited to different long-term care settings (e.g., nursing homes, residen-

tial care, and home health care) and the individuals receiving care in them. They may complement each other in various arrangements such as that of deemed status, complaint investigation and mediation, or independent confirmation of measures of satisfaction of individuals in long-term care and their families.

Beginning with the development of licensure for health workers in the nineteenth century to the current ongoing government initiatives to define and enforce quality standards, regulation and oversight have figured prominently in efforts to assess, protect, and improve the quality of health care. Basic quality standards define and specify the minimum acceptable qualifications for state licensure and for certification for participation in Medicare and Medicaid.1 This chapter focuses on the government's central role in setting and enforcing standards of quality for formal long-term care. It highlights the current status of the basic standards, the survey process for monitoring and assessing compliance, and the enforcement of the quality standards for nursing homes, residential care, and home health care. Throughout the chapter the committee provides suggestions and recommendations for further improvements at both the federal and the state levels.

CENTRAL ROLE OF GOVERNMENT

Through legislation, regulation, and judicial decisions, federal and state governments play a central role in the definition and enforcement of basic standards of quality for long-term care, particularly for publicly funded services and institutional care. In addition, regulations involving such matters as contracts or disclosure of information to consumers and the public are components of quality strategies based on consumer choice and quality improvement.

Most federal regulations of long-term care are linked to federal funding of services through the Medicare and Medicaid programs, and are administered by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Both programs have requirements for participation that health care providers must meet to receive payment.2

Federal and state governments share regulatory responsibilities for long-term care. Overall, the federal government has a dominant presence in nursing home and home health regulation through certification for

|

1 |

Those who meet specified standards may also have to meet other conditions, for example, payment of a fee to actually secure a license. |

|

2 |

Until recently, these requirements were known as “conditions of participation.” |

Medicare and Medicaid participation. States, however, play the major role in regulating other kinds of long-term care. For example, they set licensure and other standards for various kinds of residential care arrangements. States also perform many of the certification procedures under contract with HCFA.

Although basic standards for long-term care are often defined and enforced primarily through the legislative and administrative process, standards put forward from other nongovernmental sources are also important. Many professional societies, trade associations, accrediting bodies, and other organizations have set voluntary standards that operate in tandem with regulations through voluntary compliance. Voluntary standards are often intended to “raise the bar” by promoting and recognizing performance beyond a basic, legally established level. In some cases, an approved accrediting organization's standards can be “deemed” to meet certification requirements for participation in Medicare or Medicaid, as is the case with the certification of home health care agencies, discussed later in this chapter.

The central elements of long-term care regulation at the federal or state level are:

-

establishing quality and related standards for service providers;

-

designing survey processes and procedures to measure and monitor actual conditions of residents or clients and to assess compliance; and

-

specifying and imposing remedies or sanctions for noncompliance.3

These three elements of a regulatory system have been likened to “the legs of a three-legged stool” (IOM, 1986, p. 69), with each leg equally important to the effectiveness of the system. In order to assess compliance with federal Medicare and Medicaid requirements, HCFA relies on a survey and certification process, which is administered by state licensing and certification agencies. HCFA's ten regional offices are charged with the oversight and monitoring of the state survey and certification efforts for nursing homes and home health agencies.

In recent years, reporting of assessments of compliance with standards and sanctions for noncompliance has become prominent as consumer groups and others have pressed for more complete public reporting. To the extent that such reports accurately reflect quality problems, they can be useful both for policy makers and for people facing personal decisions about long-term care. Moreover, the enforcement of govern-

|

3 |

Remedies and sanctions are used interchangeably throughout this report to refer to enforcement actions against providers failing to comply with regulatory requirements. |

ment standards does not depend solely on periodic inspections by regulators or on self-enforcement by the regulated. Complaints from residents, family members, facility or agency staff, formally appointed ombudsmen, and others may help identify violations and other problems that regular, formal inspections and reporting systems may miss. Many complaints and concerns related to basic standards of quality may be voiced directly to providers, ideally prompting a constructive internal response. Beyond this “oversight-by-complaint” role, family, friends, and other visitors to the long-term care setting also provide social and practical support to those using long-term care, help paid caregivers better understand the perceptions and preferences of those they serve, and build links between long-term care and the larger community.

Arguments for and Against Regulation

Major goals of long-term care regulation have been described as (1) consumer protection, specifically, ensuring safety, quality of the care received, and legal rights of consumers, and (2) accountability for public funds used for care (IOM, 1986). With government accounting for 61 percent of nursing home and home health care expenditures (Braden et al., 1998), it has a responsibility to hold providers accountable for fiscal integrity and for the quality of care provided to beneficiaries. Medicare and Medicaid requirements of participation for nursing homes and home health care services serve both goals. States also have an obligation under their police power functions to provide oversight over the public health and safety.

Most policy makers acknowledge a particular need for federal and state regulation of long-term care. The reasons are several:

-

Regulatory protection is essential given the significant vulnerability of many of the people using long-term care, including the very old and frail, the very young, and those with dementia, mental illness, and developmental disabilities. Many people with severe chronic or disabling conditions are highly dependent on others and unable to protect themselves from abuses and neglect by caregivers. Moreover, many have no immediate family members, friends, or advocates who are able to oversee their care and protection.

-

Individuals needing long-term care frequently have multiple diagnoses and chronic conditions that require a wide array of medical and nursing services, medications, and treatments. Although some individuals have the knowledge and skills to direct their own care, others do not.

-

Those using long-term care rely heavily on nonprofessional and para-

-

professional workers, which typically means they rely on workers who have little training or expertise in providing care.

-

Much long-term care is relatively invisible, either because it is provided in the home or because it is provided in facilities without much community observation.

-

Users of long-term care often lack choice of providers or services, which limits the effectiveness of market forces in ensuring quality.

On the basis of the above, a strong argument can be made for an active government role in defining and enforcing basic standards of quality for long-term care providers. In addition, ensuring their enforcement protects those using long-term care from neglect, abuse, and mismanagement.

Critics of regulation as a dominant strategy for protecting and improving the quality of long-term care present several arguments. During public meetings, providers criticized overreliance on regulatory strategies contending that:

-

It may encourage mediocrity. They believe that too many providers concentrate narrowly on minimum requirements instead of striving for providing quality care.

-

Regulation may create barriers to innovation. What may be a necessary rule for those not motivated or able to provide quality care, could be an obstacle to others seeking creative ways to improve the quality of care and life and autonomy of those using long-term care.

-

There is a possible danger for regulation to proliferate excessively. For example, regulators concerned about marginally performing institutions and egregious instances of poor quality of care may be tempted to multiply structure and process regulations without regard to their effectiveness or costs.

-

They believe that regulations focus too single-mindedly on protection and safety as objectives. Other values such as the quality of life or autonomy of those receiving care may be underemphasized.

With regard to federal regulation of nursing homes, however, the nursing home reforms in the Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA 87) actually changed the focus from a nursing home's ability to provide care to the quality of care provided. OBRA 87 requires nursing homes participating in Medicare and Medicaid to comply with extensive standards and these standards include ensuring various residents' rights related to admission, transfer, and discharge, and the right to be free from restraints and abuse, and to promote residents' quality of life. The regulations also focus more than before on processes of care and resident out-

comes. In common with most complex human endeavors a perfect regulatory system is likely to be beyond human reach. Nonetheless, it is important for policy makers, regulators, and advocates to consider and weigh both the expected benefits and the expected burdens of regulations. Moreover, by listening to the concerns of those subject to regulation as well as the beneficiaries of regulations, policy makers may be able to develop effective, yet less costly and less resisted ways of achieving their goals. The challenge is to design and implement a system that does what it is intended to do at an acceptable cost.

BASIC STANDARDS OF QUALITY

In principle, some basic standards for long-term care could be developed that apply regardless of the setting or provider of care. In practice, however, most standards are designed for specific categories of providers or services. In general, it may be useful for policy makers, providers, consumer advocates, and others to think about standards applicable across various care settings. Such thinking may become increasingly necessary if concepts of consumer-centered and -directed care are to be developed. Indeed, regulatory standards related to outcomes have become an increasingly important objective in long-term care. This approach, however important, is beyond the scope of what the committee is able to address in this report.

Reflecting the differences in current regulatory programs in various long-term care settings, this chapter focuses on selected settings separately. As is typical of most long-term care issues, nursing homes have been the focus of most attention in standard-setting and enforcement activities. This again reflects a long history of concern about abuse, neglect, and poor quality of care in nursing homes and public concern about this frail and vulnerable group of long-term care users, who are subject to the greatest degree of provider control over their lives. The discussion that follows focuses on nursing homes, residential care facilities, home health care, and home care and other home and community-based services.

Nursing Homes

Both federal and state governments employ regulation as a strategy to protect quality of care in nursing homes. The federal government has defined standards or requirements for provider participation in Medicare, and Medicaid relies primarily on the states for assessment. The federal government retains authority to enforce compliance with nursing home standards of care, but generally delegates enforcement authority to states for other health care providers. States also independently regulate

nursing homes, for example, by licensing them to do business in the state. A few nursing homes operate only under state regulation because they choose not to seek Medicare or Medicaid reimbursement, but nearly all facilities depend on such reimbursement and, therefore, have all, most, or some of their beds certified.

This study was not intended to replicate or update the Institute of Medicine's (IOM) 1986 report by producing a detailed analysis of the implementation of that report's recommendations or generating another set of comprehensive recommendations about nursing home regulation. This committee generally endorses the directions set forth in the 1986 report and in the legislative reforms enacted in 1987. During 1998 and 1999, however, new reports and investigations of serious problems in nursing home quality and government regulation demanded the committee's serious attention. As context for the discussion of these problems, a brief review of the 1986 IOM report and subsequent nursing home legislation is useful.

The 1986 IOM Report on Nursing Home Regulation

In its 1986 report on nursing home quality, the IOM committee noted “serious, even shocking, inadequacies” in the enforcement of then-current nursing home regulations. It identified “large numbers of marginal or substandard nursing homes that are chronically out of compliance when surveyed . . . [and that] temporarily correct their deficiency . . . and then quickly lapse into noncompliance until the next survey” (p. 146). The report identified problems in four broad areas: (1) attitudes of federal and state personnel about enforcement objectives and processes; (2) federal rules and guidelines for states; (3) variation among states in policies and procedures; and (4) resources to support enforcement activities. It also addressed other problems with existing procedures for interpreting survey findings, weighting or scoring facility performance on individual standards, and aggregating performance on individual standards to determine whether a facility is in compliance with a condition of participation. It also addressed problems of the predictable timing of annual surveys and the reliance on record reviews and staff interviews, rather than interviews and observation of residents, to determine quality.

The report proposed that regulations “require, whenever possible, assessment of the quality and appropriateness of care and the quality of life . . . being provided residents, and the effects on residents' well-being” (IOM, 1986, p. 71). It called for new standards in three areas: residents' rights, quality of life, and resident assessment. The 1986 IOM report proposed regulatory reform to focus the survey and certification process more on persistent offenders; to clarify federal objectives and rules by improving training, reporting, and oversight activities for states; and to

establish a wider array of sanctions related to the seriousness of problems discovered. The report and subsequent legislation made clear that government's role was one of enforcement and not consultation. The framework also called for less reliance “on unguided professional judgments by surveyors” in determining what constitutes good care for residents with differing service needs (IOM, 1986, p. 71).

Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987—Setting Standards for Care

The Nursing Home Reform Act, a part of OBRA 87, created the most far-reaching changes in nursing home regulation since the Medicare and Medicaid programs were created in 1965. It was supported by a broad coalition of consumer, professional, and nursing home industry representatives. The legislation was generally based on the detailed recommendations of the IOM committee (1986), and delineated five major components addressing (1) resident rights, quality of life, and quality of care; (2) staffing and services; (3) resident assessment; (4) federal survey procedures; and (5) enforcement procedures (Harrington, 1998). For example, it created a new outcome-oriented survey process with two options—a standard survey and an extended survey. The standard survey required a stratified sample of residents (based on the characteristics or casemix of residents) for examining medical, nursing, and rehabilitative care; dietary services; social activities; sanitation; infection control; resident rights; and physical environment. In facilities found to be providing substandard care during the standard survey, an extended survey was to be applied, with a larger sample of residents, intended to uncover the causes of substandard care.

Continuing past practice, OBRA 87 required HCFA to contract with state agencies to survey nursing homes to certify their compliance with Medicare and Medicaid requirements. Consistent with the changes in the standards, enforcement was to focus on both processes and outcomes of care. The new inspection procedures were, however, to go beyond “paper compliance” to investigate processes and outcomes of care; interview residents, families, and ombudsmen about their experience in the nursing home; and directly observe residents and care processes. Surveys were to be unannounced and conducted every 9 to 15 months following the initial survey (but no sooner than 12 months on average for all facilities taken together) to give survey agencies some flexibility to link survey timing to past performance and also make it easier to create more unpredictable scheduling of survey visits. States could also initiate a survey in response to a resident or other complaint at any time. Resurveys were authorized after any change of ownership.

The new standards and survey procedures were implemented

through a series of regulations and transmittals published by HCFA in its State Operations Manuals.4 The first regulations implementing the act took effect in 1990; the last regulations (those related to enforcement of standards) were implemented only in 1995. The regulations established 15 major categories for compliance to cover the structure, process, and outcomes of nursing home care with specific requirements for each category. 5 Additionally, OBRA 87 requires nursing homes to provide certain services, including nursing, dietary, physician, rehabilitative, dental, and pharmacy services. It also included requirements for administrative standards including nursing aide training, a medical director, and clinical records.

The OBRA 87 standards for residents' rights included privacy, freedom from physical and mental abuse, restricted use of physical or chemical restraints, and opportunities to file grievances. The process of care and the environment should promote residents' quality of life, and services should help residents attain or maintain the highest practical level of physical, mental, and psychosocial well-being. The requirement that well-being be maximized “implied that improvements in health and functional status be achieved, when possible,” which shifted the focus away from custodial care toward rehabilitation (IOM, 1996a, p. 134). OBRA 87 was notable for requiring individual resident assessments and care plans for each resident described in the previous chapter.

The committee concluded that these basic standards of quality set forth in OBRA 87 are generally reasonable and comprehensive. As discussed in Chapter 3, research studies suggest that these standards may have contributed to improved care and outcomes for nursing home residents. Definitive, rigorous evaluation of their continuing impact on quality of care and outcomes is necessary.

State Survey Process

To monitor and assess compliance by nursing homes with Medicare and Medicaid requirements for participation, HCFA relies on a survey and certification process administered under contract by state agencies. As specified by OBRA 87, nursing home surveys gather information

|

4 |

The regulations were issued in 1988, 1989, 1991, 1992, and 1994, and the transmittals were included in the State Operations Manuals (HCFA, 1995a–c). |

|

5 |

The categories are (1) resident rights; (2) admission, transfer, and discharge rights; (3) resident behavior and facility practices; (4) quality of life; (5) resident assessment; (6) quality of care; (7) nursing services; (8) dietary services; (9) physician services; (10) rehabilitation services; (11) dental services; (12) pharmacy services; (13) infection control; (14) physical environment; and (15) administration (HCFA, 1995a–c). |

through facility visits; observations of residents; reviews of records; and interviews with residents, family members, and facility staff and management. Thus, assessments are not dependent solely on facility records and reports. HCFA has developed standardized forms, sampling methods, and survey procedures to ensure the reliability, accuracy, and comparability of state surveys of nursing homes. In a further effort to achieve consistency, HCFA's State Operations Manual (HCFA, 1999c), including the Interpretative Guidelines, provides more detail and guidance for state surveyors.

After surveying each facility, state surveyors determine whether the facility has met or not met each standard. If a facility is judged to not meet a standard, it is given a “deficiency.” Generally deficiency determinations are made by survey teams and reviewed by state supervisors. Facilities have the option to challenge the factual basis of deficiencies in an informal dispute resolution and to appeal decisions through an administrative review process.

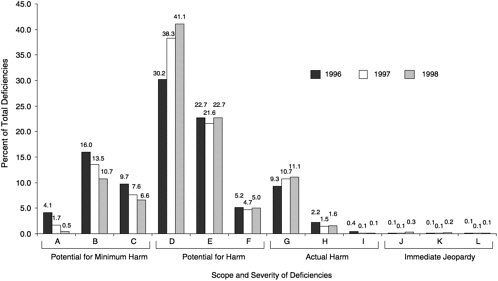

State survey results showed a clear trend in declining numbers of deficiencies after the enforcement regulations were implemented in 1995, with a small increase in 1998. As seen in Figure 5.1, the average number of deficiencies reported per facility declined from 10.8 per facility in 1991 to 4.9 per facility in 1997, a 44 percent decrease (Harrington and Carrillo, 1999). In 1998, however, the average number of deficiencies per facility increased slightly to 5.2. At the same time, the percentage of facilities reported to have no deficiencies increased from 10.8 in 1991 to 21.6 in 1997, and then dropped to 18.9 percent in 1998 (Harrington and Carrillo, 1999; Harrington et al., 2000b).

Survey results also show substantial variation across states (see Table 5.1). In 1998, the average number of deficiencies ranged from 1.9 per facility in New Jersey to 14.2 in Nevada (more than a sevenfold difference) (Harrington et al., 2000b). Similarly, the percentage of facilities with no deficiencies varied from none in Washington, D.C., to 47.7 percent in New Jersey. For the most part, the higher the average number of deficiencies in a state, the lower is the percentage of facilities reported to have no deficiencies cited (Harrington et al., 2000b).

Weaknesses in the Current Survey Process

Although the declining number of deficiencies and increase in the number of deficiency-free facilities may indicate substantially improved care in nursing homes, the analysis presented in Chapter 3 suggests that taking too optimistic a stance may be unwarranted. Instead, it may suggest weaknesses in the nursing home survey process —specifically, its ability to reliably detect quality problems. The inability or unwillingness

FIGURE 5.1 Average number of deficiencies and percent of facilities without deficiencies: United States, 1991–1998.

SOURCE: Harrington et al., 1999, 2000b.

of surveyors to detect quality problems may be one explanation, particularly following implementation of more vigorous enforcement regulations in 1995 (Johnson and Kramer, 1998; Mortimore et al., 1998; Schmitz et al., 1998).

Several studies support the conclusion that the current survey process fails to identify important quality-of-care problems. A study conducted by the University of Wisconsin in 1996, which involved 6 concurrent surveys and 23 survey observations performed by independent investigators, showed that state surveyors consistently cited fewer deficiencies in care and rated problems as less severe than did the researchers (Abt and CHSRA, 1996). Similarly, two concurrent surveys conducted for the General Accounting Office (GAO) in California also found that surveyors did not detect some serious quality-of-care problems related to hospitalizations, deaths, falls accompanied by fractures, restraint use, failure to dress and groom residents, malnutrition, infections, and pressure sores (GAO, 1998a; Johnson and Kramer, 1998). Forty concurrent surveys in ten states revealed that state surveyors were inconsistent in detecting problems related to outcomes of care, particularly those related to maintaining resident function, pressure sore prevention, and nutritional support (Johnson and Kramer, 1998). At the same time, state surveyors also cited some

TABLE 5.1 Average Number of Deficiencies per Certified Facility and Percent of Facilities with No Deficiencies, by State: United States, 1992 –1998

|

Average Number of Deficiencies per Facility |

Percent of Facilities with No Deficiencies |

|||||||||||||

|

State |

1992a |

1993a |

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1992a |

1993a |

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

|

Alabama |

6.8 |

5.4 |

7.4 |

6.7 |

6.4 |

6.1 |

5.9 |

5.3 |

6.7 |

7.9 |

7.1 |

12.0 |

7.1 |

7.4 |

|

Alaska |

6.1 |

10.8 |

4.3 |

3.2 |

2.2 |

3.6 |

3.2 |

6.7 |

0.0 |

21.4 |

15.4 |

31.3 |

21.4 |

21.4 |

|

Arizona |

5.5 |

3.6 |

7.1 |

7.1 |

5.7 |

5.1 |

6.0 |

22.8 |

23.7 |

11.9 |

2.7 |

4.9 |

5.9 |

6.2 |

|

Arkansas |

10.5 |

7.6 |

7.5 |

8.1 |

8.2 |

7.5 |

7.3 |

2.6 |

4.6 |

4.1 |

5.8 |

6.6 |

3.9 |

4.7 |

|

California |

16.2 |

17.8 |

16.2 |

11.7 |

10.7 |

10.7 |

10.4 |

2.8 |

2.4 |

1.2 |

3.3 |

4.0 |

3.0 |

1.8 |

|

Colorado |

11.7 |

6.9 |

2.5 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

2.3 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

5.0 |

28.4 |

31.0 |

33.7 |

42.8 |

34.9 |

|

Connecticut |

4.8 |

5.6 |

3.7 |

2.3 |

1.5 |

2.1 |

2.7 |

13.6 |

13.6 |

18.0 |

37.1 |

46.5 |

33.6 |

23.6 |

|

Delaware |

5.8 |

6.3 |

7.2 |

6.6 |

9.5 |

7.3 |

10.1 |

12.1 |

21.6 |

7.0 |

12.1 |

2.7 |

11.9 |

7.4 |

|

Florida |

6.3 |

5.7 |

6.8 |

7.0 |

6.1 |

6.4 |

7.2 |

16.2 |

16.4 |

10.9 |

10.5 |

15.2 |

11.0 |

10.5 |

|

Georgia |

7.5 |

5.7 |

6.1 |

5.0 |

3.3 |

2.6 |

3.6 |

12.0 |

15.6 |

14.8 |

17.3 |

34.3 |

32.1 |

23.4 |

|

Hawaii |

15.3 |

18.1 |

18.4 |

9.7 |

4.8 |

6.6 |

7.8 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

4.8 |

2.5 |

9.5 |

2.3 |

|

Idaho |

12.1 |

10.9 |

8.5 |

6.1 |

6.3 |

7.1 |

7.1 |

4.8 |

3.1 |

7.7 |

7.5 |

10.8 |

7.8 |

6.3 |

|

Illinois |

8.1 |

8.2 |

8.5 |

7.9 |

6.2 |

6.0 |

5.8 |

3.9 |

5.1 |

4.0 |

5.5 |

9.0 |

6.9 |

7.9 |

|

Indiana |

5.8 |

7.3 |

7.7 |

7.4 |

6.5 |

6.8 |

7.8 |

12.3 |

11.3 |

8.2 |

7.5 |

11.9 |

9.5 |

7.4 |

|

Iowa |

5.4 |

4.8 |

4.0 |

3.8 |

4.0 |

4.8 |

4.6 |

17.7 |

17.9 |

23.9 |

25.7 |

24.9 |

17.9 |

15.8 |

|

Kansas |

13.0 |

8.9 |

6.8 |

6.5 |

6.2 |

5.5 |

5.1 |

1.0 |

4.6 |

8.6 |

5.4 |

11.3 |

11.4 |

19.5 |

|

Kentucky |

5.3 |

4.2 |

3.1 |

4.1 |

2.3 |

3.2 |

6.0 |

33.9 |

39.0 |

37.8 |

44.9 |

56.4 |

49.2 |

13.8 |

|

Louisiana |

11.8 |

11.7 |

7.8 |

6.3 |

4.7 |

4.2 |

3.7 |

6.3 |

8.8 |

14.1 |

15.6 |

20.3 |

23.2 |

30.4 |

|

Maine |

2.9 |

3.6 |

4.5 |

4.0 |

2.4 |

2.7 |

3.3 |

37.6 |

35.2 |

13.0 |

10.4 |

32.0 |

32.8 |

13.6 |

|

Maryland |

3.7 |

2.7 |

4.0 |

4.1 |

2.6 |

2.2 |

2.4 |

29.2 |

31.8 |

21.5 |

30.1 |

34.8 |

36.7 |

37.4 |

|

Massachusetts |

3.2 |

5.7 |

4.7 |

4.6 |

3.2 |

2.6 |

2.8 |

22.8 |

13.5 |

16.7 |

22.9 |

36.0 |

47.8 |

41.3 |

|

Michigan |

16.8 |

16.1 |

13.3 |

13.6 |

9.8 |

8.6 |

9.3 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

1.4 |

3.7 |

2.7 |

3.1 |

|

Minnesota |

5.3 |

7.4 |

6.8 |

5.3 |

2.9 |

2.7 |

3.6 |

16.4 |

8.4 |

7.6 |

9.7 |

27.4 |

28.6 |

25.2 |

|

Mississippi |

11.6 |

10.6 |

10.8 |

8.0 |

4.8 |

3.9 |

4.6 |

3.1 |

7.9 |

11.1 |

12.6 |

24.7 |

27.9 |

16.0 |

|

Missouri |

9.0 |

7.9 |

4.8 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

3.6 |

4.1 |

12.0 |

14.2 |

27.4 |

25.8 |

28.2 |

29.6 |

23.0 |

facilities for deficiencies that appeared to be a function of their high prevalence of seriously impaired residents rather than poor quality care (Abt Associates and CHSRA, 1996).

The failure of surveyors to reliably detect and cite quality problems has major implications. Quality problems will persist and residents will suffer in ways that could have been avoided if an effective survey program had detected problems and required their correction. Enforcement efforts may not be appropriately directed at the worst offenders, and some nonoffenders may erroneously be penalized (Johnson and Kramer, 1998). Survey information made available to the public may mislead consumers. Finally, facilities are not given adequate feedback about quality problems, which hampers facility-level efforts to improve care (Johnson and Kramer, 1998).

Strategies to Improve the Survey Process

Following the release of the GAO studies and the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging hearings on survey and enforcement activities in 1998 and 1999, DHHS responded by announcing a number of specific steps to improve the survey and monitoring process (HCFA, 1998a). HCFA regularly reports on these steps to the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging, and consumer groups are closely monitoring this process (e.g., the Center for Medicare Advocacy, the National Citizens ' Coalition for Nursing Home Reform).6The committee generally endorses HCFA's efforts to improve the current survey process. The following section briefly reviews important areas in which efforts are being undertaken and identifies areas of potential further improvements.

Targeting Chronically Poor-Performing Facilities. In 1998, as a part of the President's initiative to ensure the health and safety of nursing home residents, federal and state regulators began to target a small list of about 100 nursing homes that had poor records of compliance with quality standards to ensure these facilities receive more frequent inspections. Targeting poor-performing facilities for more frequent surveys is consistent with OBRA 87. GAO (1998a) also recommended that HCFA target facilities with serious repeat deficiencies.

HCFA's approach to identifying poor-performing facilities is based solely on facilities with repeat violations that have caused serious harm. The approach could be improved by developing a more proactive, focused

|

6 |

Additional information on this subject can be found at www.medicareadvocacy.org and www.nccnhr.org. |

process. HCFA has statistical data that could be used to identify poor-performing facilities. These data include quarterly quality indicators (QIs) developed from the Minimum Data Set (MDS), described in Chapter 4, which identify individual residents with potential problems (such as weight loss and pressure sores) and those who have declined over time, indicating potentially poor quality of care. QIs can also be used to identify facilities with high percentages of residents that have negative QIs. HCFA also has data on staffing levels in facilities that show outliers with unusually low staffing per resident-day. Facilities with average staffing below a selected percentile—especially facilities with documented past problems—could be subjected to more frequent inspections because they are “at risk” of quality problems. The use of these types of statistical data could improve HCFA's ability to monitor facilities with potentially poor quality outcomes, without waiting for a facility to achieve two consecutive poor evaluations, each of which may cause actual harm or immediate jeopardy to residents. These proposals for more focused monitoring to target chronic poor performers do not require legislative action and generally have been accepted by government, consumer, and industry groups.

Another potentially high-risk situation that HCFA and state survey agencies should consider tracking and targeting for special surveys includes changes in key administrative and clinical staff. One recent report cited annual turnover rates of nursing home administrators at 30 percent (AHCA, 1998). Anecdotal reports reinforce the concern that leadership turnover is a problem. Logic also suggests that changes in leadership would increase instability and resident vulnerability in facilities, although there are no data to confirm this hypothesis.

Focusing on Poor-Performing Owners and Poor-Performing Chain Facilities. Although HCFA has identified some nursing home chains (multifacility organizations) that are delivering substandard care in multiple facilities, the current survey and enforcement procedures are primarily designed to survey and enforce standards in individual facilities. A multifacility chain is one that owns, leases, or operates more than one facility, according to the HCFA definition, and these account for more than half of the nation's nursing facilities (Harrington et al., 2000b). HCFA does not have an information system that accurately identifies ownership for use in monitoring performance of nursing home chains and targeting poor-performing chains.

Moreover states are required to conduct surveys whenever there is a change in ownership, but states are not always informed when there are new corporate owners. Regulations do not require the reporting of a change in ownership when a transfer of stock or the merger of another

corporation into the provider corporation has occurred (42 C.F.R 489.18). However, HCFA (1998a) has announced steps in this direction by proposing to have the database of state survey results include major state enforcement actions (e.g., decertification) against individual and corporate owners of nursing homes. Although HCFA plans to target chains with bad records across states, it does not have a mechanism yet for taking enforcement actions against a chain even when a high percentage of the chain's facilities may be classified as substandard. Improved data on ownership, changes in ownership and quality, and new survey and enforcement procedures would greatly enhance HCFA 's ability to target and monitor poor-performing chains.

Focusing on Resident Problems. After OBRA 87, state surveyors focused on physical and chemical restraints as important indicators of quality problems. However, they failed to identify serious problems of malnutrition, dehydration, undertreatment of pain, and pressure sores during the survey process (Johnson and Kramer, 1998). This situation occurred in part because surveyors were not trained to focus on these types of resident problems. HCFA now has revised its State Operations Manual, Appendix P (HCFA, 1999c), to add new investigative protocols on pressure sores, dehydration, malnutrition (unintended weight loss), and abuse prevention. These protocols should be valuable tools for surveyors to identify and evaluate problems and to standardize the survey process.

Improving Sampling Procedures and Sample Sizes. To focus adequately on serious resident problems, sampling techniques used for these surveys should be revised to target samples of higher-risk residents (including those who are newly admitted, bed-bound, or long-stay residents). GAO (1998a) specifically recommended that sampling procedures use electronic information becoming available from the MDS system on individual resident QIs to identify and sample records for “high-risk” residents. The QIs allow surveyors to detect serious potential resident problems such as malnutrition, dehydration, pressure sores, pain, and other conditions (Zimmerman, 1999). HCFA has asked surveyors to review the data for each facility and the QIs prior to conducting surveys, but the extent to which the QIs are being used by state surveyors is not known.

Another problem identified by GAO (1998a) was that the survey sample sizes were not large enough to detect problems of concern or to determine the scope of identified problems. Again, HCFA has instructed surveyors to take stratified samples to review enough residents to detect the prevalence of problems. Although HCFA has developed new instructions in Appendix P of its State Operations Manual (HCFA, 1999c) for sample size selection, the facility samples remain small (Kramer, 1999). (For a 100-bed facility, a total of 5 comprehensive resident reviews and 12

focused reviews are required.) Sample sizes clearly have to be increased, and investigations of resident care problems have to be conducted to determine the full scope and severity of each serious problem.

Reducing the Predictability of the Survey Process. When facilities are able to predict the timing of annual reviews and prepare accordingly, they can temporarily hide deficiencies in their usual performance and mask areas of poor-quality care. The problem of survey predictability was pointed out in the IOM 1986 report, and OBRA 87 attempted to address the problem by creating penalties for any individual that notified facilities about the time or date of a survey. In 1995, HCFA issued guidance to states to ensure that all surveys are unannounced but did not require that survey cycles be varied to reduce their predictability. The GAO (1999b) review of state survey activities identified the predictability of state surveys as a continuing problem and found that the timing of many surveys had not varied by more than a week for several cycles. HCFA (1998a) also reported that the surveys were highly predictable: almost all surveys were scheduled to begin on a Monday, and surveys were rarely conducted in the evening, at night, or on holidays. The main rationale for predictable schedules was to avoid overtime and have uninterrupted time on-site (HCFA, 1998a).

In 1998, HCFA took steps to make survey schedules less predictable and to increase the number of surveys conducted on weekends and nights (HCFA, 1998a). The new State Operations Manual (HCFA, 1999c, Section 7207) specifies that standard surveys must be unannounced and at least 10 percent of surveys must begin either on the weekend or evening or early morning hours. The month in which a survey begins should not coincide with the month of the previous survey. The committee fully endorses actions by HCFA to make both the numbers of months between surveys and the days and hours on which surveys occur more variable, and supports further expanding the number of surveys that are conducted on evenings and weekends.

Strengthening Consistency of Survey Determinations. As described earlier, states vary substantially in their survey and enforcement findings, and no evidence suggests that this variation is a function of corresponding variation in the quality of care provided in states. The implementation of OBRA 87 was only partly successful in improving protocols for assessing compliance, monitoring state survey agencies, and training and support for surveyors. HCFA has recognized that large differences in survey agency practices continue to exist. During the past two years, HCFA has increased its training activities of surveyors, training more than 600 federal and state surveyors to be trainers (HCFA, 1999a). Given the large number of surveyors nationally and the complexity of the survey system, more exten-

sive, comprehensive federal training is needed to bring about consistency and competency in the survey process across states (Zimmerman, 1999). The mandatory training of all federal and state surveyors should focus on survey techniques that will standardize the entire survey process, increase consistency across states, and enhance investigative and inferential decision capability.

Some experts have argued that HCFA needs to substantially improve the survey process by making it more structured to reduce unwarranted variation (Kramer, 1999; Zimmerman, 1999). These researchers at the University of Wisconsin and the University of Colorado have a contract with HCFA to develop a more structured activity, with criteria and guidelines for determining compliance with the regulations.

Strengthening the Federal Oversight Role. GAO (1999e, p. 8) documented that HCFA's ten regional offices charged with the oversight of state survey agency performance have “limitations that prevent HCFA from developing accurate and reliable assessments.” The use of comparative surveys (a federal survey completed within a few days of the state survey) is relatively minimal, even though this is inherently more accurate for oversight purposes than observational surveys of state agency staff, which are currently employed more frequently. GAO (1999e) also documented the uneven way in which regional offices monitor state agencies and the failure to hold states accountable for poor performance of their contracted survey duties.

HCFA (1999a,b) has responded with new guidelines to improve the regional office oversight of states. It has announced plans to review state performance, for example, by identifying states that report improbably high numbers of homes with no deficiencies. HCFA also proposed to take steps to correct lax enforcement processes, for example, through loss of funding and replacement of poor-performing state survey agencies. More intermediate sanctions may be necessary to ensure state compliance. HCFA, however, has not yet developed means of monitoring the performance of the regional offices in their oversight role.

Improving Complaint Investigations. In the past, HCFA survey procedures required states to investigate within two working days the most serious complaints that allege immediate jeopardy to the health and safety of residents. However, the time, scope, duration, and conduct of investigations of other types of complaints are determined by state survey agencies. GAO (1999c) found that states frequently understated the seriousness of the complaints (thus avoiding the requirement to investigate within two working days) and more generally failed to investigate serious complaints promptly. GAO (1999c, p. 3) also reviewed the nursing home complaint investigation process and found that “HCFA reporting systems for nurs-

ing homes' compliance history and complaint investigations do not collect timely, consistent, and complete information.” In addition, some states used procedures or practices that may limit the filing of complaints (such as asking for written complaints). HCFA directions and oversight of complaint investigations were found to be minimal.

In response to the GAO (1999c) study, HCFA has agreed to undertake actions to improve the complaint investigation process and to establish a complaint category for allegations of “actual harm” and to investigate these complaints within ten working days. Complaints of immediate jeopardy are to be investigated within two working days. HCFA also agreed to strengthen the federal oversight of the state complaint investigation system and allow the regional offices to conduct verification surveys of complaint investigation. Also, the information system requiring states to enter all complaints into the On-Line Survey and Certification Assessment Reporting (OSCAR) System will be improved. HCFA has requested and the administration has proposed new funds for its nursing home initiative, including improvement of the survey system (White House, 2000). HCFA has also developed a contract to study the complaint investigation system and to improve the system. The committee supports the importance placed by HCFA on improving the complaint investigation system. It is a key to protecting the health and safety of nursing home residents.

Certifying the Accuracy of Nursing Home Data. Because surveys include reviews of residents' medical records, the accuracy of these records is essential to reliable and valid survey results. The GAO (1998a) report on quality problems in California nursing homes noted suspicious gaps in information and implausible entries in the sample of records it reviewed. A study of nursing home records on dietary intake found that nursing home staff often incorrectly record the amount of food consumed by residents (Kayser-Jones et al., 1997). Another study found that records on restraint use and removal were highly inaccurate (Schnelle et al., 1997). Nursing home staff have testified about requests or orders to falsify nursing home records (U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging, 1998). Some errors undoubtedly arise from poor record keeping, which—although a problem in need of correction—is a lesser concern than deliberate falsification of records. In terms of the latter, at the present time no specific “severe” penalties exist for falsification of records or false reporting. New penalties may be needed for deliberate falsification of medical records.

Enforcement of Standards

The goal of the enforcement process under OBRA 87 was to achieve sustained facility compliance with federal requirements of quality care.

Prior to this legislation, the only sanction available was decertification, a penalty with such serious consequences for residents of a sanctioned facility that regulators were reluctant to apply it. The revised enforcement system was intended to give surveyors more flexibility in fitting remedies to the seriousness of deficiencies and to make the actual imposition of intermediate sanctions more likely.

The sanctioning authority under OBRA 87 allowed the imposition of civil money penalties, denial of payment for new admissions, temporary management, immediate termination, and other remedies or sanctions. The law required that all states enact the list of “intermediate sanctions” (sanctions other than decertification) and that they be imposed for violations of residents' welfare and rights as well as for health and safety violations. The statute required that mandatory remedies be imposed for repeated or uncorrected deficiencies and that the enforcement actions minimize the time between the identification of violations and the imposition of remedies. The law allowed all sanctions other than civil money penalties to be imposed before the administrative appeals were decided and barred HCFA from playing a consultative rather than an enforcement role.

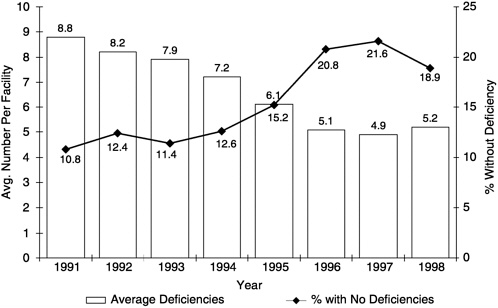

The final enforcement rules were published in the Federal Register on November 10, 1994 (59 Fed. Reg. 56,116), and became effective on July 1, 1995 (HCFA, 1995b). In establishing the enforcement rules, HCFA was prescriptive in its rating system for the scope and severity 7 of violations and in terms of the intermediate remedies that should and could be applied. Beginning in July 1995, state surveyors were required to rate all violations based on their scope and severity, and then to link sanctions to the scope and severity of the violation identified (HCFA, 1995b). Deficiencies were to be given for problems that had resulted in or could result in a negative impact on the health, safety, welfare, or rights of residents. To guide states, HCFA established a graded system for classifying deficiencies and penalties by severity and scope. As shown in Table 5.2, each deficiency is rated in one of 12 categories labeled “A” through “L” depending on the severity and scope. Facilities that do not have deficiencies exceeding the first three category levels (A–C) are considered to be in “substantial compliance” with the regulations and they are not subject to sanctions, although they are expected to correct their deficiencies. Those with deficiencies in categories higher than C are “not in substantial compliance” and are subject to intermediate sanctions or termination from the program, depending on the scope and severity of the problem.

|

7 |

HCFA uses severity to refer to the effect of a deficiency on resident outcomes; scope describes the number of residents potentially or actually affected (HCFA, 1999c). |

TABLE 5.2. Level of Deficiencies, Based on Scope and Severity of Substandard Care, and the Remedy Categories Available to States for Each Level of Deficiency

|

Scope of Deficiency |

|||

|

Severity of Deficiency |

Isolated |

Pattern |

Widespread |

|

Immediate jeopardy to resident health or safety |

Level J Required remedy category: 3 Optional remedy category: 1 or 2 |

Level K Required remedy category: 3 Optional remedy category: 1 or 2 |

Level L Required remedy category: 3 Optional remedy category: 1 or 2 |

|

Actual harm that is not immediate jeopardy |

Level G Required remedy category: 2 Optional remedy category: 1 |

Level H Required remedy category: 2 Optional remedy category: 1 |

Level I Required remedy category: 2 Optional remedy category: 1 or temporary management |

|

No actual harm, with potential for more than minimal harm, but not immediate jeopardy |

Level D Required remedy category: 1 Optional remedy category: 2 |

Level E Required remedy category: 1 Optional remedy category: 2 |

Level F Required remedy category: 2 Optional remedy categories: 1 |

|

No actual harm with potential for minimal harm |

Level Aa Required remedy category: none |

Level B Required remedy category: none |

Level C Required remedy category: none |

|

aAll facilities receiving deficiencies are required to submit a plan of correction except for those with level A deficiencies only. Remedy Categories: Category 1:

bBurke and Cornelius, 1998. Category 2:

cHarrington et al., 2000. Category 3:

SOURCE: HCFA, 1999c. |

|||

Under HCFA guidelines, however, most facilities are given a grace period, usually 30 to 60 days, to correct deficiencies. The exceptions are for facilities with deficiencies in the highest severity categories (level J through L) that cause immediate jeopardy and for those that cause harm with severe repeat deficiencies. Facilities that cause immediate jeopardy are not given the opportunity to correct deficiencies before sanctions are imposed, whereas facilities with less serious deficiencies generally are given the opportunity to correct them. Regulations also require a notice period before the sanction can take effect. Remedies recommended by states must be sent to HCFA regional offices, and a 15–20 day notice for the facility to come into compliance must be issued (HCFA, 1999c). In cases of immediate jeopardy, the sanction can be put into effect after a two-day notice. 8 Civil money penalties can be assessed retroactively for noncompliance that occurred between surveys.

In addition, “substandard quality of care” is defined as one or more deficiencies that constitute either immediate jeopardy (of any scope), actual harm, or at a level of no actual harm but with a potential for more than minimum harm. For the latter two categories the scope of the harm must be a “pattern” or be “widespread.” Substandard quality of care in these scope and severity levels is limited to deficiencies in the regulatory requirements under resident behavior and facility practices, quality of life, or quality of care (HCFA, 1999c). Facilities receiving a determination of substandard quality of care are subject to loss of their authority to conduct nursing aide training, which consequently may make the hiring of nursing aides difficult. In addition, the facility is subject to all of the above sanctions relevant to the scope and severity of the deficiency.

Enforcement Trends and Variability

Review of deficiency ratings over a three-year period show that few deficiencies (0.6 percent in 1998) were classified as causing immediate jeopardy (in the highest categories for scope and severity). Figure 5.2 shows that the percentage of deficiencies designated as having a minor or minimal impact declined over the period while the percentage of total deficiencies classified as having the potential for actual harm in isolated situations (level D) increased from 30.2 to 41.1 over the three year period, but levels E and L remained about the same. The percentage of deficiencies that were considered to have caused actual harm in isolated situations (level G) increased somewhat over the three years, but all other categories appeared to be about the same (Harrington and Carrillo, 1999;

|

8 |

The new guidelines give states opportunity to impose some remedies directly. |

Harrington et al., 2000b). Only a few facilities are being given deficiencies for immediate jeopardy at the level J or higher (about 0.6 percent of facilities) where sanctions would be imposed without the opportunity to make corrections.

Continuing Weaknesses in Enforcement of Standards

The U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging (1998, 1999), GAO (1998a, 1999b,c,e), and HCFA (1998a) have identified a number of continuing problems with the enforcement of nursing home standards. The federal goals to achieve both compliance and continued compliance with federal standards have yet to be fully met. For instance, GAO (1999b) examined the enforcement of federal nursing home regulations and concluded that although HCFA has taken steps to improve the oversight of nursing homes, it is unable to ensure that nursing homes maintain compliance with federal health care standards. According to GAO, more than one-fourth of the facilities had deficiencies that caused actual harm to residents or placed them at risk of death or serious injury and many others had serious deficiencies.

GAO (1998a) reported that once the state survey agency identified deficiencies in the quality of care, it was ineffective in achieving the remedial state of consistent compliance with the law. Nearly 10 percent of California nursing homes serving thousands of residents were cited twice in a row for “actual harm” violations, strongly suggesting that these homes were not correcting problems identified by surveyors. California took relatively few disciplinary actions against facilities cited for repeated “actual harm” violations. Between 1995 and 1998, nearly three-quarters of the 122 facilities in California cited for serious deficiencies in at least two consecutive years never had federal intermediate sanctions take effect (GAO, 1998a). GAO (1998a) also found that over the course of two standard surveys conducted between 1995 and 1998, one-third of the nursing homes (407 out of 1,370) had serious violations that caused death, seriously jeopardized residents' health and safety, or were considered to be substandard.

Strategies to Improve the Enforcement Process

Reflecting recommendations from consumer groups, GAO, and others, HCFA has taken a number of steps to correct identified problems in the enforcement of federal nursing home standards.

Definitions of Facility Problems. Until recently HCFA's definition of poor-performing facilities applied to relatively few facilities. A facility had to

be cited on its current survey and on one of its two previous standard surveys for substandard quality of care. HCFA now has expanded the definition to include facilities cited for isolated cases of actual harm in two or more surveys (HCFA, 1999c). Facilities are allowed to correct deficiencies, and sanctions are optional if only one such deficiency has occurred.

In addition, HCFA's definition of what constitutes a widespread deficiency has been limited and needs revision. “Widespread” was considered to take in situations where all or nearly all of a home's residents were affected by a problem, including those for whom the deficiency could not have occurred (e.g., those who were continent could not be characterized as lacking a plan for achieving continence) (Edelman, 1997). In a facility where most of the residents on a nursing care unit were negatively affected by poor care, the deficiencies would not be considered widespread, but rather would be classified as a pattern. This has the effect of limiting the ability to assess sanctions in situations where they may be indicated.

Elimination of the Grace Period Before Sanctions Are Imposed. HCFA (1998a) has recently issued a memorandum to the states phasing out the grace period that allowed time for facilities to achieve compliance with regulations before penalties were applied. Apparently at odds with OBRA 87 mandates, HCFA's 1995 enforcement regulations established a grace period, which allowed facilities with deficiencies to make corrections before being subject to intermediate sanctions (Edelman, 1998a–c). GAO (1998a) reported that grace periods were granted to 98 percent of facilities in California and to 99 percent of facilities nationwide. These grace periods often allowed 30–45 days before a penalty could be applied. Only facilities whose deficiencies posed immediate jeopardy to residents' health or welfare or those that were defined as poor performers were denied the opportunity to correct deficiencies before remedies were imposed. The revised HCFA State Operations Manual (HCFA 1999c, p. 7–27) states that facilities will not be given an opportunity to correct before remedies are imposed (1) when they have deficiencies of actual harm (at level G) or a more serious level on the current survey and on the previous survey; (2) when they received a per-instance civil money penalty; (3) when the deficiencies were for immediate jeopardy; or (4) when the facility had previously been terminated. Except in these instances, the opportunity to correct without sanctions remains unless a state chooses to establish additional criteria. The committee urges HCFA to accelerate the schedule for phasing out the grace period.

Revisiting All Facilities Before Sanctions Are Lifted. In principle, sanctions are supposed to remain in place until a facility corrects the deficiencies

and a revisit has been completed. Until recently, HCFA did not require on-site revisits of facilities found to have deficiencies that did not cause serious harm or substandard care. Instead, these facilities were allowed to self-certify when they came into compliance (GAO, 1998a). As a result, only about 15 percent of facilities were subject to revisits, even though some of these facilities had repeatedly been designated as poor performers and as providers of substandard care.

Following the GAO (1998a) study, HCFA adopted a policy that all problem facilities with recurring serious violations should receive an onsite visit before a state was considered to be in compliance with the regulations. The HCFA State Operations Manual (1999c) has been revised to indicate that facilities with deficiencies causing actual harm or more must have an on-site revisit of the facility. This policy is a substantial improvement over the previous one.

Limiting the Use of Civil Money Penalties. In 1996, HCFA issued guidelines that urged states to limit the imposition of civil money penalties (CMPs) to situations of immediate jeopardy to the health and welfare of residents or uncorrected deficiencies at the time of a revisit of a poor-performing facility (Edelman, 1998a–c). This policy contradicted the intent of OBRA 87 for intermediate remedy provisions and the HCFA regulations. HCFA now has lifted the moratorium on the collection of certain civil money penalties but still limits CMPs to serious deficiencies which HCFA defines as levels G, H, and I, or as “substandard care.” The penalty may be assigned retroactively for the number of days out of compliance since the last standard survey. The manual made clear that CMPs may be issued for up to $10,000 per day or per instance when a deficiency constitutes immediate jeopardy or involves actual harm.

Federal Procedures Create Lengthy Delays. Although the law says that all remedies other than civil money penalties can be imposed immediately pending an appeal, the notice of sanctions and the federal appeals process can result in lengthy delays in implementation of CMPs. The sanctions and civil monetary penalty system is seriously hampered by a backlog of administrative appeals that can last for several years and CMPs cannot be collected until the appeal is resolved (GAO, 1999b). The appeals may take two to five years and the weight of the administrative backlog has approached gridlock. The administration has requested additional funds from Congress to increase the number of hearing officers for appeals to speed the process, which appears to be needed. Even with more funds, the process set forth in the HCFA State Operations Manual (1999c) appears unnecessarily cumbersome and time-consuming. More work is needed to streamline the enforcement process.

Access to Information About Enforcement Actions Against Facilities. In response to requests by advocacy organizations, HCFA agreed to make deficiency reports, including the scope and severity of deficiencies and other information about individual facilities, available on the Internet in 1998. HCFA has established this information about nursing homes on its Web site at www.hcfa.gov/Medicare/NHCompare. This is an important first step toward making information more accessible to the public. The committee hopes that this information will be expanded and improved as experience is gained to include all sanctions, remedies, and appeal decisions.

Stricter Provisions for Decertification and Minimum Time Periods for Recertification of Terminated Facilities. One important additional step is to target facilities that move in and out of compliance ( “yo-yo” facilities). As the IOM committee reported in 1986, many facilities have had repeated violations that have caused serious harm and injury to residents and these facilities generally have escaped the imposition of any sanctions because they were repeatedly allowed to correct the violations. This problem has not gone away, as documented by GAO (1998a). In addition, terminated facilities can fairly easily gain recertification without a specific waiting period. For example, of the 16 facilities terminated in California between 1995 and 1998, 14 were reinstated and 11 were reinstated under the same ownership as before the termination. Of the 14 reinstated homes, 6 were cited for new, serious violations (GAO, 1998a).

HCFA has explained that termination from the Medicare and Medicaid programs is an option when there is a condition of immediate jeopardy or when there is a history of noncompliance and other remedies have failed to bring about compliance (HCFA, 1999c). Facilities that are decertified can immediately reapply for certification and must be admitted back into the program if they meet the compliance requirements. Facilities are required to pass two surveys within a one- to six-month period verifying that the reason for termination no longer exists and that the provider has maintained continued compliance. HCFA termination procedures have not been effective in eliminating those facilities that are chronic poor performers from the program. In December 1999, HCFA changed the rules about readmitting facilities that are terminated. It now requires a “reasonable assurance” process for facilities terminated from Medicare (Transmittal 13, § 7321, pp 7–43).

Temporary Management. Despite provisions in OBRA 87, for a wide range of sanctions, states still find it difficult to apply temporary management to persistent serious offenders. Use of temporary management would avoid decertification, which results in relocations causing distress to residents and families. Temporary management or receivership is a serious

alternative sanction against a poor-performing provider, but it is less disruptive than decertification. Yet few temporary managers have been imposed (HCFA, 1998a), and it is not clear why. HCFA should consider studying the barriers to using these procedures and streamlining its procedures so that they could be more quickly and easily applied in appropriate circumstances.

Informal Dispute Resolution Process. In 1995, HCFA adopted an informal dispute resolution process that allowed nursing facilities to challenge the imposition of deficiencies in a process separate from the formal appeals process (HCFA, 1999c). This process was not mandated by OBRA 87 and was opposed by consumer advocates as a method of delaying the imposition of intermediate sanctions. The process may be a significant factor in the decline in deficiency citations and associated sanctions, and it may also be adding to state agency costs. On the other hand, the process may be resolving misunderstandings and reducing the number of formal appeals. HCFA has not evaluated the informal dispute resolution process, but such an evaluation should be conducted.

Recommendations for Nursing Home Assessment and Enforcement

The above discussion of federal and state enforcement of nursing home regulations in this chapter has identified problems with both the identification of quality care and the enforcement of compliance with quality standards. The committee also reviewed and made suggestions throughout the discussion for needed improvements in the various federal and state survey and enforcement activities. HCFA's recent initiatives are welcome and should be sustained and expanded. The following recommendation provides major directions for continued improvement of the assessment and enforcement of regulatory quality standards:

Recommendation 5.1: The committee recommends that:

-

Federal and state survey efforts focus more on providers that are chronically poor performers by surveying them more frequently than required for other facilities, increasing penalties for repeated violations of standards, and decertifying persistently substandard providers;

-

HCFA's monitoring in all areas of state survey and sanction activities be improved by ensuring greater uniformity in state surveyor interpretation and application of survey regulations, and be reinforced by assistance and sanctions as necessary to improve performance; and

-

An analysis be commissioned to examine if increased funding is needed to HCFA to improve the state survey and certification processes for nursing homes.

RESIDENTIAL CARE FACILITIES

Standards for Residential Care

The regulation of residential care occurs primarily at the state level. The federal regulation directly affecting residential care is the 1976 Keys amendment to the Social Security Act. This law was passed to protect Supplemental Security Income (SSI) recipients from substandard board and care homes. States are required to certify that all facilities in which significant numbers of SSI residents reside meet appropriate quality standards. In general, the states have broad discretion in carrying out this oversight. The state role includes licensing and monitoring compliance with health and safety regulations, such as building codes, food handling, medication storage and distribution, and staffing requirements. A GAO (1999a) study found that oversight by HCFA was limited and that states rarely sanctioned facilities for providing substandard care.

Medicaid is increasingly paying for residential care under its 1915(c) home and community-based service (HCBS) waiver program (Harrington et al., 2000f). It relies on each state to design and administer its own program. The Medicaid HCBS waiver program requires states to provide assurances that necessary safeguards have been taken to protect the health and safety of beneficiaries receiving long-term care—including residential services (other than room and board)—under the waiver. States vary in their regulation of the range of services covered by the Medicaid waiver program, and little is known about the specific nature or effectiveness of their efforts (Harrington et al., 2000d). The committee is seriously concerned about the lack of descriptive information and assessments of current state regulatory activities. A systematic approach to collecting and monitoring all aspects of state regulatory activities for residential care should be developed.

State Variability in Standards and Enforcement for Residential Care

Residential care arrangements have filled an important need in the continuum of care for long-term care. State standards for these care arrangements including assisted living facilities, a relatively recent subset of residential care, are highly variable (Mollica, 1998; Hawes et al., 1999). As described in Chapter 2, this variability begins with the very definition of

the kinds of settings subject to particular regulations and extends to such matters as who can be served (admission and discharge criteria), what services can be provided, what staff are required, and how personal and social living spaces must be configured.

The complexity of the situation facing state regulators is illustrated by the fact that there are numerous levels and types of residential care including group homes, foster homes, assisted living facilities, residential care facilities, mental health facilities, mental retardation facilities, personal care homes, supportive living facilities, and habilitation facilities. Moreover, they are called by more than 25 different names with multiple categories and titles within states (Lewin/ICF and James Bell Associates, 1990; Hawes et al., 1993).

The lack of uniformity in names of programs is repeated in state regulatory standards for different types of facilities. A 1995 study of adult foster care, for example, found that just half of the 26 states with adult foster care required licensing by a state health licensing agency, and that public funds were used to pay for services for half or more of residents in 18 states (Blanchette, 1996).

State licensing survey activities are sometimes divided among agencies or divisions. For example, mental health programs may survey residential care for people with severe mental illness, developmental disability programs may survey facilities for people with mental retardation, and still other agencies may survey facilities serving primarily elderly people. Hawes and colleagues (1993) documented that there were 62 agencies in 50 states and the District of Columbia that license homes serving a predominantly elderly population. Many additional agencies license facilities serving residents with psychiatric illnesses or mental retardation and developmental disabilities, and some states require accreditation (Hawes et al., 1993). Other states license homes that provide treatment for those with serious mental illness and substance abuse problems.

In addition to conventional regulation by licensure, some state care management programs have public agencies operating more as contractors than as regulators. These programs may operate under Medicaid HCBS waiver provisions, which allow them to place individuals in residential care settings for certain services. In their oversight role, case managers review these settings for placement, and for removal of residents whose needs are not being met. Few studies, if any, have been conducted to evaluate state oversight of residential care settings through these types of case management mechanisms.

Concerns about the widespread belief that the current board and care homes have many inadequacies and are responsible for an increasingly frail population led the AARP, in 1990, to contract with the Research Triangle Institute to conduct a national study of state board and care

regulations (Hawes, et al, 1993). Data were collected from state regulatory and funding agencies, and local ombudsman care management agencies involved in the provision of board and care. Some of the key findings place board and care homes in perspective. State agencies identified a total of 31,942 licensed homes that met the study criteria of serving a primarily elderly population and of being subject to licensing requirements. States varied from about 24 to more than 4,000 homes. The survey found that most states did little either to identify unlicensed homes or to require unlicensed homes to become licensed.

State inspection processes are fairly similar—most states inspect facilities once a year—however, enforcement actions are quite limited and generally only in the form of corrective action plans. Thirty-seven agencies had the authority to issue provisional licenses, usually as a sanction against homes with deficiencies, but only 17 reported using that authority three or more times in the year preceding the interviews. Fines and other more severe forms of sanctions, even when authorized, were seldom imposed (Hawes et al., 1993).

Such variations in state policies reflect different perceptions about whether congregate residential care is primarily a medical service or primarily a housing arrangement intended to allow people to age in place in a noninstitutional setting that is meant to emphasize autonomy and privacy. Unresolved questions remain about the acceptable role and extent of regulatory standards in residential care settings.

Weaknesses in State Regulation of Residential Care

Very little has been done to evaluate the effectiveness of current policy and regulatory practices in residential care. The few studies undertaken have raised serious questions about the effectiveness of state regulation and licensure promoting quality in residential care. As stated earlier, Hawes and colleagues (1993) found that state regulation and enforcement of standards were weak. Sanctions were used infrequently. Most states did not have the authority to ban admissions, and when they did have the authority, it was rarely used.

A GAO (1997a) study of assisted living reported problems with many facility contracts with residents, usually called admission contracts. Under these contracts, residents generally agree to limit the facility 's potential liability for specific risks that the resident assumes, such as a fall when climbing stairs. However, the GAO (1997a) report stated that “a recent limited study of industry practices noted that contracts had no standard format, varied in detail and usefulness, and in some cases were vague and confusing” (p. 6). GAO's conclusion was based on findings reported by the American Bar Association and by Consumer Reports. “For example,