6

Strengthening the Caregiving Work Force

The previous chapter focused on regulatory standards and their enforcement. This chapter examines federal and state personnel standards for various long-term care settings. It reviews the literature on the relationship between staffing and quality of care, and presents recommendations for improvements. This chapter also examines the training and education of personnel; hiring and employment issues, including registries and background checks before hiring; and barriers to a stable workforce, with particular emphasis on wages and benefits. Finally, the chapter discusses the management and organizational capacity needed to improve quality of care.

Provision of formal long-term care to the population requires an adequate, skilled, and diverse work force. Registered nurses (RNs), licensed practical nurses (LPNs), and nursing assistants or aides (NAs) and home health aides represent the largest component of personnel in long-term care. Other professionals—including physicians, social workers, therapists (physical, occupational, and speech), mental health providers, dietitians, pharmacists, podiatrists, and dentists—provide many different kinds of essential services to at least a subset of those using long-term care. Non-professionals, who provide the majority of personal care services, such as assistance with eating or bathing, have a major impact on both the health status and the quality of life of long-term care users. In addition to direct care providers (or caregivers), administrative, food service workers, housekeeping staff, and other personnel play essential roles in long-term care.

As shown in Chapter 2, in 1998, nursing homes, personal care facilities, residential care, and home health and home care agencies accounted for nearly 3.2 million jobs. Of these jobs, 1.18 million, or 37 percent, were paraprofessionals (including nursing assistants, personal care aides, and home health care aides), 9 percent were RNs and 8 percent were LPNs (BLS, 2000). Approximately 57 percent of the paraprofessional workers were employed by nursing facilities, 28 percent by home care agencies, and 15 percent by residential care facilities or programs in 1998 (BLS, 2000).

Long-term care services are labor intensive so the quality of care depends largely on the performance of the caregiving personnel. Personnel standards vary considerably across long-term care settings. For purposes of this report, “staffing levels” include numbers of staff, ratios of staff to residents, and the mix of different types of staff in nursing homes and residential care facilties. In home care, staffing levels cannot be discussed in these terms since each client is served individually and agencies are staffed to meet client needs. Rather, the committee considered the amounts and types of services provided to clients with various needs. In a labor-intensive field such as long-term care, the numbers, training, and competence of staff are widely viewed as critical to the quality of services.

Most of the research on the relationship between quality of long-term care and the number and type of staff and their expertise and skills relates to nursing homes. Some studies have examined home health care workers, but few of these studies have examined the relationship between work force characteristics and quality of care. Little is known about the relationship of staff to quality of care in other long-term care settings.

In addition to staffing levels, a key issue is whether the work force in long-term care has adequate education and training to provide high quality of care to individuals. Federal standards have been set for some personnel in nursing homes and home health agencies, but not for personnel providing care in other types of long-term care settings. Some states also have their own requirements for personnel, particularly for the regulation of health professionals and long-term care administrators. These requirements vary across states.

This chapter discusses the caregiving work force separately for each setting. The committee examined existing standards and reviewed the available empirical evidence and research literature on the relationship of staffing patterns and quality. The committee deliberated on the need for changes in standards, education and training issues, and the work environment.

NURSING HOMES

Federal and State Nursing Home Staffing Standards

To participate in the Medicare or Medicaid programs, long-term care facilities must meet federal certification requirements established by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA, 1994). The Nursing Home Reform Act, embedded in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA 87), included a number of provisions related to staffing, which were implemented by the HCFA in a series of regulations and transmittal letters (HCFA, 1994, 1995a–c). The legislation required increased nurse staffing and social work services and set minimum training requirements for nursing assistants. Specifically, OBRA 87 requires nursing facilities certified for Medicare and Medicaid to have licensed nurses on duty 24 hours a day; an RN on duty at least 8 hours a day, 7 days a week; and an RN director of nursing. The statute permits the director of nursing and the RN on staff for 8 hours a day to be the same individual. Furthermore, each nursing home is required to have a medical director responsible for the medical services of the facility residents. Facilities with 120 or more beds must have a full-time person with a bachelor's degree in social work or a related field. HCFA regulations also require social activities; medically related social services; dietary services; physician and emergency care; and pharmacy, dental, and rehabilitation services (including physical, speech, and occupational therapies, which are mentioned explicitly) (HCFA, 1995a–c).

More generally, the law requires “sufficient staff” to provide nursing and related services to attain or maintain the “highest practicable level” of physical, mental, and psychosocial well-being of each resident. The federal law and the implementing regulations, however, do not provide specific standards or guidance about what constitutes “sufficient staffing.” Registered and licensed nurse requirements are not adjusted for facility size or casemix. The HCFA survey and certification program does not have procedures for auditing staffing levels or for monitoring the accuracy of staffing data reported by facilities.

In addition to federal requirements, some states have licensing requirements for staffing in nursing facilities that go beyond the federal staffing requirements, although they vary widely across states (NCCNHR and NCPSSM, 1998). In a recent survey, 21 states reported legislative action or interest in increasing staffing standards (NCCNHR and NCPSSM, 1998). California increased its minimum nursing home requirements for direct caregivers to 3.2 hours per resident-day (excluding administrative nurses) (California State Budget Act, 1999). The committee generally endorses the

OBRA 87 standards and the states' efforts to improve the staffing requirements in nursing facilities.

Current Staffing Levels in Nursing Homes

Staffing data are available from the On-Line Survey and Certification Assessment Reporting (OSCAR) System, the Medicare time studies conducted by HCFA, and periodic national sample surveys conducted by the federal government.

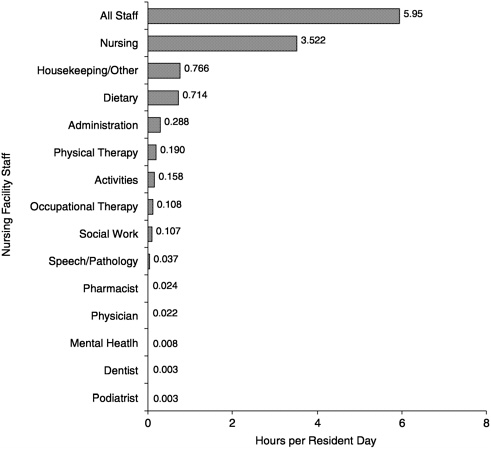

OSCAR System. OSCAR data, collected during the certification surveys by state agencies that verify compliance with all federal regulatory requirements, show staffing data reported by facilities for the two weeks prior to the survey. Figure 6.1 presents the available OSCAR data on all staff in nursing facilities in the United States during calendar year 1998. It shows that average total staffing hours were 5.9 hours per resident-day for all nursing facilities in the United States in 1998. Nursing staff represented 59 percent of the total personnel hours. Housekeeping and other staff was the second largest category, with 0.77 hour (46 minutes) per resident-day, and dietary staff had 0.71 hour per resident-day. The activity staff averaged 0.16 hour (10 minutes) per resident-day. All other staff were less than 7 minutes per resident-day.

Table 6.1 shows that the average number of hours for registered nurses (including nurse administrators) was 0.74 hour per resident-day. LPN hours were 0.69 hour per resident-day and NA hours were 2.09 hours in 1998. Total nurse staffing per resident-day was 3.52 hours. When the total hours are divided by three (8-hour) shifts per day, each resident was receiving about 15 minutes of RN time per shift, 14 minutes of LPN time, and 42 minutes of nursing assistant time per shift.

Averages for the country as a whole, however, mask substantial variation among states and among facilities within states. As seen in Table 6.1, there are wide variations in staffing levels for different types of facilities. Hospital-based nursing facilities had almost twice as many total hours of nursing care and 4 times as many registered nurse hours as freestanding nursing facilities. Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) for Medicare-only residents had 2.3 times as many total nursing hours and 6 times as many registered nursing hours as facilities with Medicaid-only residents. Larger facilities had higher nurse staffing hours than smaller facilities. Some facilities report very low nurse staffing levels. Table 6.2 shows that of the total certified nursing homes, 2,701 facilities (19 percent) provide less than 2.7 nursing staff hours per resident-day.

FIGURE 6.1 Mean staffing hours per resident day for nursing facilities in the United States surveyed in calendar year 1998. NOTE: Facilities with inaccurate resident data or incomplete staffing data (497 facilities) were removed. Facilities with staffing levels in the lower 1 percent and the upper 2 percent (1,211) (calculated separately for Medicaid only facilities and Medicare certified facilities) were removed.

Medicare Staffing Time Studies. In 1990, Congress passed legislation requiring HCFA to develop a Nursing Home Casemix and Quality Demonstration program (OBRA, 1990). This HCFA project developed a method for classifying nursing home residents into 44 different Resource Utilization Groups (RUGs) based on a study of resident characteristics in relation to the facility staff time expended to provide care, including nursing and therapy staff (Fries et al., 1994).1 These studies were then used to develop

|

1 |

For details of the methods, see Fries et al. (1994). For information about the quality indicators developed from Minimum Data Set data, see Zimmerman et al. (1995). |

TABLE 6.1 Nursing Staff Levels per Resident Day, by Facility Type and Region for Nursing Homes: United States, 1998

|

Nursing Staff |

||||||

|

Facility Characteristics |

Number of Facilities |

Percent of Facilities |

Total |

Registered Nurses |

Licensed Practical Nurses |

Nursing Assistants |

|

Mean Hours |

||||||

|

Total |

13,396 |

100.0 |

3.52 |

0.74 |

0.69 |

2.09 |

|

Type of facility |

||||||

|

Hospital based |

1,702 |

12.4 |

5.79 |

2.13 |

1.22 |

2.44 |

|

Non-hospital based |

11,991 |

87.6 |

3.20 |

0.54 |

0.62 |

2.04 |

|

Certification |

||||||

|

Skilled nursing facilities for Medicare only |

1,054 |

7.7 |

6.95 |

2.91 |

1.50 |

2.53 |

|

Skilled nursing facilities for Medicare or Medicaid |

10,909 |

79.7 |

3.28 |

0.58 |

0.63 |

2.07 |

|

Nursing facilities for Medicaid only |

1,730 |

12.6 |

2.98 |

0.43 |

0.58 |

1.97 |

|

Size |

||||||

|

1–99 beds |

6,843 |

50.0 |

3.78 |

0.91 |

0.73 |

2.14 |

|

100+ beds |

6,850 |

50.0 |

3.26 |

0.56 |

0.66 |

2.04 |

|

Region |

||||||

|

West |

2,030 |

14.8 |

3.63 |

0.81 |

0.61 |

2.21 |

|

South |

4,487 |

32.8 |

3.63 |

0.67 |

0.84 |

2.11 |

|

Northeast |

2,481 |

18.1 |

3.62 |

0.84 |

0.62 |

2.16 |

|

North Central |

4,695 |

34.3 |

3.32 |

0.72 |

0.62 |

1.98 |

|

SOURCE: Harrington and Carrillo, 2000. |

||||||

a Medicare payment system for use by the five states participating in the demonstration starting in 1995. Ultimately, Congress adopted a Medicare prospective payment system (PPS), implemented by HCFA in 1998.

Prior to the implementation of the PPS, HCFA commissioned three major studies to measure staff time in nursing facilities. The purpose of these studies was to define the relationship between resident resource utilization and nursing and therapy staff time. The RUGs were derived in

TABLE 6.2 Distribution of Combined Nursing Hours per Resident Day in All Certified Nursing Facilities: United States, 1998

|

Percentile |

Average Hours per Resident Day |

Number of Hours |

Cumulative Number of Hours |

|

0–9 |

0.90–2.45 |

1,343 |

1,343 |

|

10–19 |

2.46–2.70 |

1,358 |

2,701 |

|

20–29 |

2.71–2.88 |

1,320 |

4,021 |

|

30–39 |

2.89–3.04 |

1,397 |

5,418 |

|

40–49 |

3.05–3.20 |

1,347 |

6,765 |

|

50–59 |

3.21–3.37 |

1,428 |

8,193 |

|

60–69 |

3.38–3.58 |

1,360 |

9,553 |

|

70–79 |

3.59–3.91 |

1,381 |

10,934 |

|

80–89 |

3.92–4.65 |

1,386 |

12,320 |

|

90–100 |

4.66–16.67 |

1,373 |

13,693 |

|

NOTE: Median (50th percentile) = 3.21 hours per resident day. Mean = 3.52 hours per resident day. N = 13,693 certified nursing facilities. Facilities with inaccurate resident data or incomplete staffing data (497 facilities) were removed. Facilities with staffing levels in the lower 1 percent and the upper 2 percent (calculated separately for Medicaid-only facilities and Medicare-certified facilities) (1,211 facilities) were removed. SOURCE: Harrington and Carrillo, 2000. |

|||

part and updated based on these time studies. The 1995 and 1997 time studies were used primarily to set reimbursement rates for a Medicare prospective payment system (Burke and Cornelius, 1998; Reilly, 1998). From the perspective of staffing requirements, the major concern with these studies has been that nursing and therapy time was based on existing practices in facilities and not on the staffing time required to meet the needs of residents.

The average time per resident-day for different types of nursing staff from HCFA time studies in 1995 and 1997 (averaged together) includes direct and indirect (e.g., administrative) nursing time. Table 6.3 compares HCFA time study data with OSCAR staffing data. The average time, based on HCFA time studies, was 4.17 total nursing hours per resident-day (Burke and Cornelius, 1998). This figure was higher than the 3.52 hours reported on OSCAR, probably because the time studies focused on facilities with high numbers of Medicare residents rather than on those with only Medicaid residents.

The new Medicare PPS pays nursing facilities based on the resident casemix. The Medicare payment formula was based on the amount of time that nurses and therapy staff are expected to provide for Medicare residents with different types of impairments. Nursing facilities are not, however, required by HCFA to provide the hours of time for which they

TABLE 6.3 Comparison of Average Nursing Hours per Resident Day for OSCAR Data, HCFA Time Studies, and Time Proposed by Experts

|

Nursing Staff |

OSCAR Data, 1998a |

HCFA Time Studies 1995–1997b |

Time Proposed by Expert Panelc |

|

Average Hours per Resident Day |

|||

|

Total |

3.52 |

4.17 |

4.55 |

|

Registered nurses |

0.74 |

1.15 |

1.15 |

|

Licensed practical nurses |

0.69 |

0.70 |

0.70 |

|

Nursing assistants |

2.09 |

2.32 |

2.70 |

|

NOTE: times listed include all administrative nursing time and indirect care. aHarrington et al., 1999. c Harrington et al., 2000. |

|||

are paid under Medicare. Thus, payment is not tied directly to staffing levels in nursing facilities.

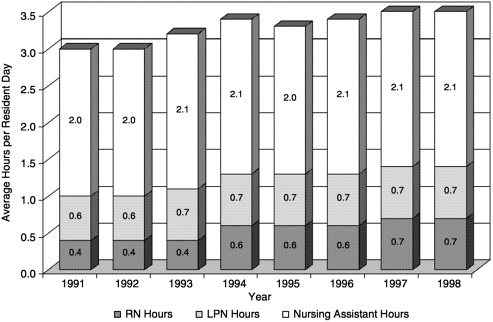

There are some indications that staffing ratios have increased somewhat in recent years. The total nursing hours per resident-day reported on OSCAR data for all facilities has gradually increased. Figure 6.2 shows that the total number of hours per resident-day in nursing facilities, as reported in OSCAR, was 3.0 hours in 1991. By 1998, this total was 3.5 hours per resident-day. Much of the increase in hours was due to increases in RN hours over that period. The slight increase (less than 10 percent) observed may be attributed in part to the requirements of OBRA 87 and in part to the increased acuity of residents and the consequent staffing required to care for residents who need specialized services.

Relationship of Staffing and Quality of Care

Many factors influence the quality of care provided to residents by staff and the quality of life of the residents. Staffing levels and staff characteristics are critical structural elements. In addition, education and training of staff, attitudes and values, job satisfaction and turnover of staff, salaries and benefits, and management and organizational capacity of the facility are all factors affecting quality.

As reviewed in the 1996 Institute of Medicine report on the adequacy of nurse staffing in hospitals and nursing homes (IOM, 1996a), a number of studies have shown a positive association between nurse staffing levels and the processes and outcomes of nursing home care (see for example

FIGURE 6.2 Average nursing hours per resident day in all certified nursing facilities: United States, 1991–1998.

SOURCE: Harrington and Carrillo, 2000.

Linn et al., 1977; Nyman, 1988b; Munroe, 1990; Cherry, 1991; Spector and Takada, 1991; Aaronson et al, 1994; Cohen and Spector, 1996).

Nyman (1988b) found that nursing hours per patient-day were positively related to three quality measures. Kayser-Jones and colleagues (1989) found that inadequate staffing resulted in poor feeding of residents and inadequate nutritional intake, which contributed to resident deterioration and hospitalization. Munroe (1990) found a positive and statistically significant relationship between the quality of care (measured by deficiencies) and higher ratios of RN and LPN hours per resident-day and lower turnover rates. Spector and Takada (1991) found that higher staffing levels and lower RN turnover rates were related to improvements in resident functioning. Lower staffing levels were associated with high urinary catheter use, low rates of skin care, and low resident participation in activities. Braun (1991) found that higher RN hours were related to lower mortality rates. Cherry (1991) also found that increased RN hours were positively associated with a composite of good outcome measures (fewer decubitus ulcers, catheterized residents, or urinary tract infections, and less antibiotic use). Cohen and Spector (1996) found that higher ratios of RNs to residents, adjusted for resident casemix, reduced the likelihood of

death and that higher ratios of LPNs significantly improved resident functional outcomes. The relationship between inadequate staffing and malnutrition, starvation, dehydration, undiagnosed dysphagia, and poor oral health of residents has been documented (Kayser-Jones, 1996, 1997; Kayser-Jones et al., 1997; Kayser-Jones and Schell, 1997). Kayser-Jones and colleagues (1999) showed that nearly all nursing home residents studied in two facilities had inadequate fluid intake. They attributed this finding to inadequate staffing supervision to provide care to nursing home residents with dysphagia, severe cognitive and functional impairment, and aphasia or inability to speak English.

A study of Minnesota nursing homes found that in the first year after admission to a nursing home, the licensed nursing hours (but not nonlicensed) were significantly related to improved functional ability, increased probability of discharge home, and decreased probability of death. However, when limited to chronic care residents the role of professional nursing hours disappeared (Bliesmer et al., 1998). Harrington et al. (2000h) showed that higher nurse staffing hours, particularly RNs, were associated with fewer nursing home deficiencies. In contrast, one longitudinal study of nursing home residents in Massachusetts found that better health outcomes (e.g., survival time, functional status, incontinence, and mental status) were not related to higher RN staffing levels (Porell et al., 1998).

Bowers and Becker (1992) found that nursing assistants reported inadequate time to provide high quality of care and the widespread use of techniques for cutting corners required to manage the workload. Foner (1994) reported that workload demands for productivity in nursing homes were in conflict with the need to provide individualized care. Two studies identified reports of psychological and physical abuse of residents by nursing assistants, which were found to be related to the stressful working conditions in nursing homes (Pillemer and Moore, 1989; Foner, 1994). Some of the staff problems can be directly related to poor wages, limited or no health benefits, and high turnover rates (IOM, 1996a).

The most important factor in determining staffing levels should be the resident casemix within facilities. Previous studies have shown a strong positive relationship between casemix adjusted resident characteristics and nurse staffing time (Arling et al., 1987; Cohen and Dubay, 1990; Zinn, 1993a,b; Fries et al., 1994). Thus, facilities with higher casemix levels should require more nursing staff time to meet resident needs.

Several studies have shown the importance of nursing management by professional nursing staff and gerontology specialists in making improvements in quality of care (Schnelle, 1990; Schnelle et al., 1990; Hawkins et al., 1992). The knowledge, hands-on care, and leadership of RNs were essential to sustained quality improvement interventions (Schnelle, 1990).

Other studies have demonstrated the important role that gerontological nurse specialists and geriatric nurse practitioners play in improving quality (Kane et al., 1988; Mezey and Lynaugh, 1989, 1991). Improved outcomes of care and fewer hospitalizations with the use of gerontological nurses have been documented (Mezey and Lynaugh, 1989, 1991; Buchanan et al., 1990; Mor, 1999). Mor (1999) found lower rates of risk-adjusted hospitalization (but not mortality) for residents in facilities that have a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, but he did not find an effect of RN staff ratios on hospitalization rates. The 1986 IOM Committee on Nursing Home Regulations encouraged nursing homes to employ specially trained gerontological nurses. The committee supports the recommendation of the IOM Committee on the Adequacy of Nurse Staffing in hospitals and nursing homes that nursing facilities use geriatric nurse specialists and geriatric nurse practitioners in both leadership and direct care positions (IOM, 1996a). Most nursing homes, however, do not employ nurse practitioners in direct care positions.

In summary, the research evidence suggests that both nursing-to-resident staffing levels and the ratio of professional nurses to other nursing personnel are important predictors of high quality of care in nursing homes. Research provides abundant evidence that participation of RNs in direct caregiving and the provision of hands-on guidance to NAs in caring for residents is positively associated with quality of care. The research literature, however, does not answer the question of what particular skill mix is optimal (IOM, 1996a). Nor does it take into account possible substitutions for nursing staff and ways to best organize all staff. Moreover, as discussed later in this chapter, nurse staffing levels alone are a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for positively affecting care in nursing homes. Training, supervision, environmental conditions, leadership and management, and organizational culture (or capacity) are essential elements in the provision of quality care to residents. Overall, there is a need for sufficient, well-trained, and motivated staff to provide consumer-centered care in nursing homes, as required in OBRA 87.

A few studies have examined the contributions to residents' well-being of other types of staff providing non-nursing services in nursing homes. One example is therapy. A study of physical and occupational therapy services in a clinical trial found therapy to have positive benefits for functional status and costs of care (Przybylski et al., 1996). Another clinical trial showed only modest benefits of physical therapy on mobility (Mulrow et al., 1994). A retrospective study of medical records reported that patients receiving high-intensity physical therapy had positive outcomes (Chiodo et al., 1992). A survey of nursing homes found that facility administrators perceived a positive relationship between the provision of daily rehabilitation therapy and the discharge of patients (Kochersberger et al., 1994). In a recent study, direct care staffing hours for these profes-

sional services (e.g., therapists and activity directors) had a consistent, significant negative relationship with deficiencies in nursing homes (Harrington et al., 2000h). In summary, the research reported has generally shown the importance of professionals providing therapy services in nursing homes. However, these studies offer little guidance on the appropriate level of nursing and medical care for different types of residents. Overall, a strong need exists for research to examine the direct effects of health professionals (social workers, activities personnel, therapists, dietitians, dentists, pharmacists, and other personnel) on the quality of nursing home care. Although it is obvious that these specialties are of critical importance, the amount and type of services delivered by such professionals have to be studied so that clear recommendations can be developed to improve quality of care.

Should Staffing Standards Be Increased?

Many clinicians, researchers, and consumer groups consider the current federal nursing home staffing standards to be inadequate to ensure quality of care in nursing homes. The National Citizens' Coalition for Nursing Home Reform (NCCNHR), a nonprofit organization formed in 1975 by a coalition of residents, advocates, ombudsmen, professionals, nursing home providers, and other groups, has criticized federal standards and recommended minimum federal staffing ratios (Burger et al., 1996). Based on expert opinion, NCCNHR (1995) adopted a recommended minimum staffing standard of 4.42 hours of total nursing time, adjusted for each nursing facility's casemix. These recommendations were endorsed by the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare and by the National Association of Directors of Nursing Administration in Long-Term Care (Mohler and Lessard, 1991; Mohler, 1993; NCCNHR, 1995).

An expert panel convened in 1998 at New York University for an invitational conference on nursing staff, casemix, and quality in nursing homes (Mezey and Kovner, 1998; Harrington et al., 2000c). This panel recommended an overall minimum nurse staffing level of 4.55 hours per resident day, including administrative staff [see Table 6.3]. It further recommended one full-time RN director of nursing and a full-time assistant director of nursing for facilities with 100 beds or more (proportionately adjusted for smaller facilities). In addition, it recommended that at least one RN nursing supervisor be on duty at all times (24 hours a day, 7 days a week) in each nursing home facility and that facilities of 100 beds or more have a full-time RN director for in-service education (proportionately adjusted for smaller facilities), who would be responsible for the administration and supervision of an ongoing training program for staff at all levels. The panel also recommended an increase in staffing levels at

mealtimes, so that one staff member would be available for 30 to 60 minutes to assist each dependent individual with eating. Finally, it also recommended adjustments upward in staffing for increases in resident casemix.

The Omnibus Budget and Reconciliation Act, 1990 required the Secretary of Health and Human Services to conduct”. . . a study and report to Congress . . . on the appropriateness of establishing minimum caregiver to resident ratios and minimum supervisor to caregiver ratios for skilled nursing facilities.” For a number of reasons, work on the study was delayed by HCFA. The due date for the report to Congress was extended to January 1, 1999. HCFA released the phase I report of the study in summer 2000. A range of problems have been noted among nursing home residents, including increased incidences of severe bed sores, malnutrition and dehydration, and abuse and neglect. The study found a strong relationship between staffing and quality and concluded that there may be critical ratios of nurses to residents below which nursing home residents are at substantially increased risk of quality problems (HCFA, 2000). No date is set yet for completion of phase 2 of the project. The committee is pleased that HCFA has completed phase 1 of the study, and urges HCFA to expedite the completion and release of the full study.

As discussed in Chapter 4, the committee found few studies of productivity and efficiency in nursing homes or of management practices that promote quality of care. The goal for nursing homes should be to have appropriate levels and mix of personnel who can organize the work to provide good care in an efficient manner.

In summary, the committee found a wide range of staffing levels in nursing facilities. Many facilities have adequate staffing levels and provide high quality of care to residents. However current staffing levels in some facilities are not sufficient to meet the minimum needs of residents for provision of quality of care, quality of life, and rehabilitation. As shown above, research provides abundant evidence of quality-of-care problems in some nursing homes and such problems are related at least in part to inadequate staffing levels.

The IOM (1996a) study, requested by Congress to examine the adequacy of nurse staffing in hospitals and nursing homes, found that a positive relationship exists between nursing staffing and quality of care, and that trends in resident characteristics suggest an increasing need for professional nursing presence. It further concluded that there was abundant evidence that participation of RNs in direct caregiving and provision of hands-on guidance to NAs in caring for residents is positively associated with quality of care. The IOM (1996a) report therefore recommended that more registered nurses be added to the staff in nursing homes and that by year 2000 a 24-hour presence of registered nurse coverage in

nursing facilities be required as an enhancement to the current 8-hour requirement specified under OBRA 87. That committee recognized that its recommendation entails additional costs and, therefore, recommended that Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements be adjusted accordingly. This committee endorses the recommendations of the 1996 IOM report (IOM, 1996a). It regrets, however, that no directive or initiative is in place yet to implement these recommendations.

The committee concludes that in view of the increased acuity of nursing home residents, federal staffing levels must be made more specific and that the minimum level of staffing has to be raised and adjusted in accord with the casemix of residents. The objective should be to bring those facilities with low staffing levels up to an acceptable level and to have all facilities adjust staffing levels appropriately to meet the needs of their residents, by taking casemix into account. To ensure that the needs of residents for quality care are met, the committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 6.1: The committee recommends that HCFA implement the IOM 1996 recommendation to require RN presence 24 hours per day. It further recommends that HCFA develop minimum staffing levels (number and skill mix) for direct care based on casemix-adjusted standards.

Since July 1998, Medicare has been paying skilled nursing facilities based on the casemix of residents and HCFA's time study estimates of staff required to provide care for each RUG category. The Medicare rate calculation includes the amount of time for each type of nursing staff (RNs, LPNs, and NAs) that provides care for each RUG category. Therefore, increasing the minimum standards to those already paid for in Medicare PPS rates, in theory, would not increase Medicare costs. Although the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 cut Medicare nursing home reimbursement rates, some funds were restored by Congress in a budget passed in the fall of 1999. For a full discussion of reimbursement issues, see Chapter 8.

Twenty-six state Medicaid agencies also paid for nursing home care based on the casemix of residents in 1998 (Harrington et al., 2000g). Thus, there is a precedent for tying Medicaid reimbursement to the amount of staff time required to provide care for different types of residents. Analyses reviewed in Chapter 8 suggest that some state Medicaid reimbursement rates for nursing homes are extremely low and may not be sufficient to cover the cost of meeting minimum federal standards for quality of care. Low Medicaid reimbursement formulas and methods may discourage nursing homes from increasing staffing levels. Any increase in mini-

mum staffing requirements should be related to reasonable adjustments in Medicaid reimbursement rates that pay for increased staff.

Recommendation 6.2: The committee recommends that Congress and state Medicaid agencies adjust their Medicaid reimbursement formulas for nursing homes to take into account any increases in the requirements of nursing time to meet the casemix-adjusted needs of residents.

The cost of the additional staffing can be estimated by examining the differential time between the current staffing levels and the average facility staffing level needed, multiplied by the average wages of nursing home staff. Medicaid costs estimates would depend on the minimum requirements established by HCFA and the current staffing levels that are built into state Medicaid rates. Some states have rate methods that would allow increased staffing costs to be passed through in their rates. Other states would have to increase reimbursement rates to take into account the staff increases in cases where the states' rates did not cover the increased requirements. Facilities already meeting the proposed staffing standards would have no new costs, but facilities operating below the minimum would be required to increase their staffing levels (see Table 6.3 for facilities with the lowest staffing). Depending on the staffing standards adopted, the increased costs could range from $1.5 billion to $3.7 billion. Of this total, Medicaid would pay 67 percent (because it pays for 67 percent of residents), and these costs would be split approximately in half between the federal and state governments. Although the cost increases for staff would be substantial, they would represent only about a 4 percent increase in the total $87.5 billion spent on nursing homes in 1998 (Levit et al., 2000).

The American Health Care Association (AHCA, 1999) reported that the average RN wages per hour were $16.88, LPN wages were $12.88, and the NA wages were $7.44 in 1997. Since RNs represent 20.6 percent, LPNs 19.5 percent, and NAs 59.9 percent of the total nursing staff, the average nursing home wage per hour for nurses was about $10.43 in 1998. If the minimum requirements were set at the median of 3.21 hours per resident-day, the 1,343 facilities with the lowest staffing levels would have to increase staffing by 1.67 hours; 1,358 facilities would have staffing increased by 0.625 hour; 1,320 facilities would have to increase staffing by 0.415 hour; 1,397 would have to increase it by 0.245 hour; and 1,347 would have to increase it by 0.085 hour. The total increase in staffing would be about 409,600 hours per day in these facilities, if each facility is assumed to average 100 residents. At $10.43 per hour for 365 days, the total costs of

the increase in staffing for a full year would be about $1.55 billion dollars. Another approach is to estimate the cost of increasing the average nursing hours reported on OSCAR (3.5 hours per resident-day) to the average hours reported on the HCFA time study (4.17 hours per resident-day) for all nursing facilities. This would result in a 0.67-hour increase per resident-day multiplied by $10.43 per hour for 1.5 million residents, times 365 days per year. The total cost of this increase would be about $3.3 billion.

Although difficult to estimate, increased professional nurse staffing levels might—under certain circumstances—produce some savings for the Medicare and Medicaid programs. For example, if an increased presence of professional nursing reduced the incidence of medical problems requiring hospitalization, some savings would accrue to offset higher staffing costs (Kayser-Jones et al., 1989; Kayser-Jones and Schell, 1997). If better staffing improved staff morale, the results might include higher worker productivity, lower turnover, and reduced on-the-job injuries, which are very common in nursing homes (IOM, 1996a). High personnel turnover is expensive. For example, replacement costs of staff are estimated at four times the employee's monthly salary when the costs of recruiting and training are included (Pillemer, 1996). Better staffing might even reduce the costs of supplies and drugs. For example, Phillips et al. (1993a) estimated that a reduction in the use of restraints actually saves facilities money by improving resident outcomes.

Reporting and Research Requirements

Effective monitoring of staffing levels depends on accurate, timely reporting by facilities. HCFA already requires facilities to report on their resident characteristics on a quarterly basis. The committee believes that HCFA should require nursing facilities to provide quarterly reports on number and type of staff and staff stability. Facilities should certify the accuracy of these data, and HCFA should review and audit the data regularly. HCFA should consult with consumer groups and with the nursing home industry in designing staffing report forms. By comparing staffing data with resident characteristics, HCFA will be better able to monitor compliance with staffing requirements and quality standards. To promote accountability to consumers and the public, HCFA should make these data available to the public on the Internet along with information on how to use and interpret the data as indicators of quality of care.

Furthermore, the committee believes that HCFA should give high priority for research on staffing in nursing homes, and seek research funds to examine the actual time and the staff mix required to provide adequate processes and outcomes of care to nursing home residents. As new data become available about the

appropriate staffing levels to meet the needs of residents, federal staffing standards and facility staffing practices should be modified appropriately.

EDUCATION AND TRAINING OF STAFF IN NURSING HOMES

Registered and Licensed Practical Nurses

The issues of education and training are important to quality of care in nursing facilities (Maas et al., 1996). Registered nurses in nursing homes have substantially lower levels of education (74 percent with an associate or diploma degree) than nurses in hospitals (59 percent with associate or diploma degrees) (Maas et al., 1996; Moses, 1997). Many nurses in nursing homes have had no training in gerontology or chronic disease management (Bahr, 1991; Maas et al., 1996). Yet studies suggest the importance of nursing management by professional nursing staff and gerontology specialists in making improvements in quality of care (Schnelle, 1990; Schnelle et al., 1990; Hawkins et al., 1992; Anderson and McDaniel, 1998). All nursing homes should have a commitment to ongoing continuing education in the care of the chronically ill and disabled and to gerontological nursing. Training in resident assessment and care planning is also very important for nurses, particularly since some nursing schools do not provide training in the basic assessment of patients or in the supervision and management of ancillary personnel. Some states have recommended that each licensed nurse have at least 30 hours of training every two years, but few states have specified the particular areas of training needed.

Nursing management and leadership are central to providing high quality of care in nursing facilities, especially given the complex needs of residents. At present, there are no specific federal requirements for directors of nursing in nursing homes other than that they be RNs. Unlike hospitals, where only rarely do directors of nursing (DONs) have less than a bachelor's degree and often have graduate education, in nursing homes they often are graduates of either a diploma program or an associate degree program at a two-year college (Bahr, 1991; Moses, 1997), and rarely have advanced clinical training in gerontology. A bachelor's degree is considered the basic qualification for entry into professional practice by the American Academy of Nursing and the American Nurses' Association. Leadership and management are not part of the basic preparation in the diploma and associate degree programs. Furthermore, turnover among DONs is high, their salaries are relatively low, and they have limited opportunities for advancement —factors not conducive to strong leadership. Given the number of employees, budgets, and complexity of care provided in nursing facilities today, strong leadership from the DON

is a prerequisite for provision of high-quality and cost-effective care (IOM, 1996a).

One of the problems with establishing training standards is that little research has been conducted to determine what would be a desirable standard for training. The amount and frequency of training, the nature and scope of training, and special needs for training (e.g., new technologies) should be examined by researchers to provide guidance in setting professional standards. Nonetheless, nursing facilities should place greater emphasis on educational preparation in the employment of new DONs and licensed professionals.

Nursing Assistants

Nursing assistants make up the largest proportion of caregiving personnel in nursing homes. They provide most of the direct care and spend the most time with residents, but they receive little training for provision of care in a nursing facility. The organization, use, and education of NAs make a substantial difference in the care, comfort, and health of nursing home residents, and also in the morale and health of the NAs. OBRA 87 required NAs in nursing homes to have a minimum of 75 hours of training and 12 hours of in-service training per year, and they must pass a competency test within four months of employment (see OBRA 87, sec.1819(b)(5)). Once the nursing assistants pass the competency examination, they are considered “certified nursing assistants.” The training is specified in the legislation (the training for home health aides is the same as that for nursing assistants in nursing homes), but the exact nature of the training, certification, and requirements varies by states. Some states have gone beyond the minimum federal training requirements for nursing assistants. For example, California requires 150 hours of training before the NAs can take their competency test and work in facilities beyond the first four months of employment (Harrington et al., 2000c).

Medicare conditions of participation for nursing homes specify the training of nursing assistants required to provide personal care services. The training content must address each of the following subject areas through classroom and supervised practical training totaling at least 75 hours, with at least 16 hours devoted to supervised practical training. The training generally includes communication skills; observation, reporting, and documentation of patient status and the care or service furnished; reading and recording temperature, pulse, and respiration; basic infection control procedures; basic elements of body functioning; maintenance of a clean, safe, and healthy environment; recognition of emergencies and knowledge of emergency procedures; understanding of physical, emo-

tional, and developmental needs of, and ways to work with, the populations served, including the need for respect, privacy, and property; and appropriate and safe techniques in personal hygiene and grooming including adequate nutrition and fluid intake.

Supervised practical training means training in a laboratory or other setting in which the trainee demonstrates knowledge while performing tasks on an individual under the direct supervision of a registered nurse or a licensed professional nurse. Each nursing assistant must pass a competency evaluation that addresses each of the subjects in the training program, and each NA must complete a performance review at least every 12 months. The quality of training varies substantially across facilities and states. Although states set some standards for training and competency exams, these are minimal and not closely enforced. Some are concerned that on-the-job training by nursing homes is weak and recommend that such training be provided by community colleges or adult education programs, which would ensure that minimum standards for training are met by all. However, research has not addressed these issues surrounding training.

With the increased acuity of nursing home residents and the consequent complexity of care needed today, some argue that training should be significantly increased and, especially, tied to the clinical problems identified in nursing homes (Burgio and Burgio, 1990). Training for NAs in nursing homes should include clinical care of the aged and disabled, occupational health, and safety measures. NAs themselves are reported to say they need more training and experience, particularly in the management of residents with dementia, depression, and aggression, and in effective communication (Mercer et al., 1993). Ideally, training programs should be structured to build-in career development for NAs. Increased levels of training are expected to increase the quality of care in nursing facilities. Unfortunately, research is lacking on the effect of different levels and types of training on the quality of care provided in nursing homes. There is some agreement among experts, however, that there is a relationship between the level and type of training and the quality of care that nursing assistants provide.

Nursing Home Administrators

Probably no position in a nursing home is as central as that of the administrator. Currently, federal Medicare and Medicaid requirements do not set any standards for administrators. Some states have established their own nursing home administration boards and requirements, but these vary across states.

Christensen and Beaver (1996) and Singh (1997) have argued that the employment stability of nursing home administrators is a significant factor influencing the quality of care provided to residents in nursing homes. Singh and Schwab (1998) examined factors that cause the high turnover of nursing homes administrators (41 percent or higher annually). They found higher retention when administrators are involved in decision making, treated fairly, and given reasonable goals to achieve. They also found that turnover was lower in independently-owned facilities, nonprofit facilities, and larger-sized facilities than in chains, for-profit, and small facilities.

Singh and Schwab (1998) found that opportunities for educational and professional development were important factors in the retention of nursing home administrators. Castle and colleagues (1996) found a relationship between the number of hours worked by nursing home administrators, controlling for other factors, and the prevalence of pressure ulcers and the use of psychotropic medications. Castle and Banaszak-Holl (1997) showed that administrator's education, job tenure, and professional involvement were positive predictors of innovations in nursing homes.

Medical Directors and Practitioners in Nursing Homes

Medical services are relatively unavailable in day-to-day nursing home care. Medical practitioners have less of a presence except in rehabilitation and other facilities that provide more intensive medical services and supervision. Most nursing home residents, for whom scheduled physician visits are required, rarely leave the nursing facility to visit a primary care physician. Nonetheless, nursing home services must be provided in accord with care plans authorized and periodically reviewed by physicians. The attentiveness and leadership of the medical community are important in efforts to improve the quality of long-term care.

Medicare certification regulations promulgated in 1976 made medical directors responsible for quality oversight in nursing homes. OBRA 87 further strengthened the role of medical directors by defining their role. Medical directors are to provide oversight and participate in drug utilization review and quality assurance programs and to work with attending physicians on appropriate drug therapies and medical care issues.

The American Medical Directors Association has encouraged professional interaction and assisted in providing training programs for medical directors (Fortinsky and Raff, 1996). This effort appears to be leading to a greater level of interest by, and involvement of, physicians. Medical directors are reported to be spending more time in facilities to address quality issues (Fortinsky and Raff, 1996), but their overall time in facilities is less than 1.5 minutes per resident-day (see Figure 6.1). Zimmer et al.

(1993) pointed out that the average medical director spends little more than three hours a week in a facility. Many medical directors agree that such time is not sufficient and that more involvement by medical directors is essential (Levenson, 1993; Tangalos, 1993).

Few nursing homes have staff physicians; rather, they rely on community-based attending physicians to provide medical care to nursing home residents. Reports suggest that medical care in nursing homes tends to be provided by a small group of physicians, suggesting there may be problems accessing medical care for some nursing home residents (Fortinsky and Raff, 1996). Little research has focused on the role of physicians and the relationship of physician services to nursing home quality. Karuza and Katz (1994) studied physician staffing patterns in nursing homes in New York and found different organizational and practice patterns ranging from attending physicians in the community to in-house physicians and closed staff models. They argued that the lack of in-house physicians in many facilities was a problem for handling emergencies, diagnosing and treating acute medical problems, and managing infection control. Nurse practitioners can also play an important role in nursing home care by acting as substitutes for physicians or by working with physicians. Research studies on the value of nurse practitioners are discussed earlier under nursing home staffing.

Physician responsibility and liability for long-term care problems have emerged as new issues in nursing homes. Although medical directors are accountable for quality of care in nursing facilities, they generally have little authority within facilities (e.g., in terms of hiring and firing staff and in setting administrative policies) and little authority over attending physicians (Levenson, 1993). Attending physicians ' actions, especially in drug selection and rehabilitation orders, may affect the financial operations of facilities, although the physicians themselves are paid for their medical services under Medicare Part B (i.e., they are not covered by PPS).

The growth of managed care also has important implications for physician services in nursing homes, especially as more acutely ill patients are being referred for posthospital care. Managed care plans and their physicians provide medical care to their members in nursing facilities. Reuben and colleagues (1999) described the approaches that three health maintenance organizations (HMOs) have taken to providing primary care for long-stay nursing home residents. HMOs that provided more visits to members in nursing homes had significantly fewer emergency room visits and hospitalizations compared with HMOs that provided fewer visits. These managed care programs performed significantly better on more than half of the process quality measures (e.g., response to falls and fevers), but no differences were observed in mortality. This study showed

the value of a strong physician component devoted to nursing facility care and meticulous maintenance of the program.

One approach to improving the quality of nursing home care would be for facilities to vest greater authority and responsibility in medical directors for medical care services and require attending physicians and nurse practitioners to follow facility medical policies and procedures. Few facilities have established such requirements. A more stringent approach would be to develop closed panel staff to provide medical services within facilities so that attending physicians would have to meet certain education and credentialing standards before they could provide care to residents within the facility. The committee believes that nursing homes should develop structures and processes that enable and require a more focused and dedicated medical staff responsible for patient care. These organizational structures should include credentialing, peer review, and accountability to the medical director. Physicians should participate in the development of, and be responsive to, facility policies and procedures and regulatory requirements.

Physicians, nurse practitioners, and other primary care providers in long-term care need to have expertise relevant to the populations they are serving and the settings in which they are providing care. Those providing care to children, developmentally disabled, mentally disabled, chronically ill, or other special populations require expertise specific to each of these groups. In providing nursing home care to older populations, geriatric training is especially important, including training in multidisciplinary approaches to care, teamwork, and supervision of diverse professional and paraprofessional caregivers.

Medicare reimbursement policies could also help strengthen the quality of medical services provided to nursing home residents. In 1991, significant changes were made in physician reimbursement for nursing facility visits (Tangalos and Stone, 1993). Although the American Medical Directors Association supports the minimum visit requirements for residents to prevent resident abandonment by physicians, it argues that the appropriate number of physician visits should be based on patient acuity and medical necessity and not on arbitrary limits. The committee is concerned that HCFA rules do not adequately recognize the need for medical judgments that take into account the multiple complex medical problems that many nursing home residents have. Arbitrary limits set by fiscal intermediaries on the number of visits should be removed. The committee believes that HCFA should make clear Medicare and Medicaid regulations for physician services in nursing homes and allow the number and type of services provided to be based on residents' medical needs and the severity of their illness.

RESIDENTIAL CARE SETTINGS

Relationship Between Staffing and Quality

The committee found very little research examining the relationship between quality of care and the work force in residential care settings or even documenting the structure, process, or outcomes of care in these settings. Some researchers have expressed concerns about the quality of the personnel working in residential care settings (see Hawes et al., 1999), and periodic newspaper stories on assisted living provide case reports of problems. Also, a General Accounting Office (GAO, 1999a) study of assisted living facilities in four states found that more than one-fourth had been cited by state licensing, ombudsman, or other agencies. Frequent problems include poor care to residents and insufficient, unqualified, and untrained staff.

Based on participants' judgments, the Consumer Consortium on Assisted Living (CCAL, 1996) raised questions about the appropriate resident-to-staff ratio (taking casemix into account); management's understanding of the value of staff; ongoing training and staff development; supervisory systems to coordinate and oversee care delivery; and staff burnout. This group called for the development of standards or criteria for residential care staffing and staff training (CCAL, 1996).

Since residential care services are not provided under the Medicare and Medicaid programs (except under some state Medicaid waivers), there are no federal requirements for residential care personnel. States have the primary responsibility for regulating residential care facilities, and some do have staffing requirements. States vary considerably in their requirements for the work force, and some states have no educational requirements beyond a high school diploma for administrators. More than three-quarters of the work force in residential care settings, such as board and care homes and assisted living facilities, are unlicensed personal care workers and home health aides, while RNs and LPNs constitute less than 3 percent of the positions in these settings (Feldman, 1998).

The survey of board and care facilities in ten states, described in previous chapters, found 92 percent of the licensed homes and 62 percent of unlicensed homes provided personal care, such as assistance with activities of daily living (Hawes et al., 1995a). Most facilities were providing supervision or administration of medications, but only 21 percent had any licensed nursing staff (RNs or LPNs). Some states have passed nurse delegation acts that allow RNs to delegate medication administration to nursing assistants or personal care workers. Of staff giving injections, 28 percent were unlicensed with no formal training or expertise in giving injections. Only one state (Oregon) reported a program for training and

certifying nursing assistants who pass medications. When staff were tested on their knowledge of aging and care practices or medications, only 14 percent of operators and staff scored at an acceptable level. Many of the professional nursing services provided in residential care facilities were arranged through home health care agencies. Since the conduct of that survey, however, licensing requirements in only 24 states and the District of Columbia allow nonnurses to administer medications—all of them include in-house medication training requirements. Five states require staff to be certified, 12 states require staff to complete a state- or Nursing Board-approved training course, nurse delegation protocols apply in 7 states, and physicians may authorize administration of medication in 1 state (Keren Brown-Wilson, personal communication, May 9, 2000).

Staffing requirements varied across states, but in general did not seem to address the individual needs of the residents. Ten agencies permitted admission or retention of bedfast residents, and 54 permit the retention of chairfast residents. However not all of those states impose staffing requirements. As an increasing number of frail and disabled people are admitted, this staffing situation becomes a health and safety issue (Hawes et al., 1993).

Hawes and colleagues (1999), in a national probability survey of assisted living facilities for the frail elderly, found that nearly all of the 2,945 facilities in the study reported that they provided or arranged for 24-hour staff, housekeeping, and three meals a day. Of the total in the study, 52 percent provided RN or LPN care on a part-time or full-time basis, 27 percent arranged or provided the care, and 21 percent did not provide the care. Facilities with higher nurse staffing were more likely to admit and retain residents with more care needs.

Staffing Standards

As stated earlier, a large body of research comparable to that for nursing facilities does not exist on work force issues in residential care settings. The Assisted Living Quality Coalition (ALQC, 1998) has recommended some minimum standards for staffing. It recommended that the administrator of assisted living facilities should be at least 21 years of age with at least a high school diploma and have adequate education, experience, and ongoing training to meet the needs of residents. In addition, the ALQC recommended a demonstrated management or administrative ability to maintain the overall operations of the setting.

The ALQC (1998) further recommended that staff numbers and qualifications should be sufficient to meet the scheduled and unscheduled needs of residents for services on a 24-hour basis and to monitor changes in residents' physical, cognitive, and psychosocial status. A minimum of

one staff person should be awake and on-site at all times when one or more persons with cognitive impairments are present. More generally, staff should have “adequate skills, education, experience and ongoing training to serve the resident population in a manner consistent with the philosophy of assisted living” (ALQC, 1998, p. 84).

The coalition's recommendations have highlighted the need for states to develop more specific personnel standards and guidelines. The kinds of intensive time and resource-use studies described earlier for nursing homes have not been conducted in residential care settings. In part, this gap in information reflects variability of models, definitions, populations served, and state regulations. It also reflects the lack of Medicare and Medicaid funding for these services and the corresponding lack of incentive for policy makers to support even descriptive studies of resources associated with providing different types and amounts of care. Time and resource-use studies of the various types of personnel providing care are needed for residential care arrangements so that appropriate staffing standards can be developed. As Medicaid programs, in particular, begin to pay for more residential care services, federal and state governments have a greater interest in ensuring that these settings meet minimum standards of care and staffing.

Education and Training in Residential Care

In general, training requirements for staff in residential care facilities are set by states, not the federal government; and state policies vary. Hawes and colleagues (1995a) found that 20 percent of licensed board and care homes and 33 percent of unlicensed homes did not require any staff training. Of the facilities that required training, most did not require the training to be completed before staff began providing care.

The Consumer Consortium on Assisted Living (CCAL, 1996) reported concerns about the lack of regulated training requirements and ongoing programs for training and staff development. It recommended training staff in (1) better communication techniques with residents and with families; (2) respect for resident rights and ways to maximize resident autonomy; and (3) resident assessment and care planning activities for individualized resident care.

More generally, the Assisted Living Quality Coalition (1998) recommended that staff should have ongoing training to serve the resident population in a manner consistent with the philosophy of assisted living. It also recommended that such training be required for all staff that have contact with residents to ensure the skills necessary for providing high quality of care and monitoring changes in residents' conditions. It further recommended that in settings where residents have dementia, staff should

“have a minimum of 12 hours of dementia-specific training per year, conducted by a qualified trainer (or facilitated by a trained staff member) to meet the needs/preferences of cognitively impaired residents effectively and to gain an understanding of the current standards of care for people with dementia” (ALQC, 1998, p. 84). ALQC further recommended that in settings where some skilled nursing services are delegated to para-professional staff, that staff should meet a documented protocol for supervision, training, and education requirements.

In summary, with regard to both staffing standards and education and training requirements, states should work to bring about more standardization and consistency in staffing standards across states. Providers should take the lead in ensuring the competence of, and provision of, appropriate training to all direct care personnel employed by residential care facilities. The committee does not believe that the first course of action should be enforcement by law or regulation at the federal level. It does caution, however, that if real quality-of-care problems were to emerge that could be related to inadequate staffing or training, then external regulations may be required to protect the health and safety of the residents.

HOME HEALTH AGENCY STAFF

Relationship Between Home Health Care Personnel and Quality

Research on the linkage between personnel and quality of care provided in a person's home is difficult to undertake because of the barriers to observing the care and identifying appropriate process and outcome measures. Most studies of home health care have examined predictors of use and expenditures rather than quality of care. R.A. Kane and colleagues (1994) described the problems of measuring home-based care quality because of the multiple goals for care, limited provider control, and unique family roles. The most highly rated outcomes were freedom from exploitation, satisfaction with care, physical safety, affordability, and physical functioning (R.A. Kane et al., 1994). Kane and Blewett (1993) developed measures that could be used to study problem-specific and patient-focused elements for older people in an ambulatory care setting. Kramer and colleagues (1990) developed quality indicator groups to classify clients into groups with similar needs and quality challenges. Although few studies have assessed quality of care, there are many complaints about home health aides and personal care workers (Harrington and Grant, 1990; Eustis et al., 1993). The key to high-quality care services is worker performance, knowledge, and skills (Eustis et al., 1993).

Home Health Agency Standards for Staff

Under Medicare, home health care services mean those services provided to individuals under the care of a physician by a home health agency, under a plan established and periodically reviewed by a physician, on a visiting basis in a place of residence such as the individual 's home (Section 1861(m) of the Social Security Act [42 U.S.C. 1395x]). These services include:

-

part-time or intermittent nursing care provided by or under the supervision of a registered professional nurse;

-

physical or occupational therapy or speech-language pathology services;

-

medical social services under the direction of a physician; and

-

to the extent permitted in regulations, part-time or intermittent services of a home health aide who has successfully completed a training program approved by the Secretary.

To be eligible for Medicare home health benefits, a beneficiary must be homebound, under the care of a physician, and in need of skilled care—defined as intermittent skilled nursing services, physical therapy, speech therapy, and continuous occupational therapy. Once these conditions have been met, an individual may also receive medical social services, durable medical equipment (subject to a 20 percent copayment), and home health aide services. As long as the services are medically reasonable and necessary for the treatment of an illness or injury and certified by a physician (every 60 days), none of these services are limited to a specific time period or a specific number of visits (Vladeck and Miller, 1994).

Medicare will not pay for home health aide services unless the beneficiary also requires intermittent skilled nursing or therapy services. As a result of a court case (Duggan v. Bowen) settled in 1988, HCFA enlarged the definition of skilled care beyond the hands-on procedures (e.g., wound care, tube feeding) that had traditionally comprised skilled nursing care, to include certain services requiring skilled nursing judgment. Under this enlarged definition, individuals could receive home health aide coverage (Bishop and Skwara, 1993; Cohen and Tumlinson, 1997).

When Congress enacted OBRA 87, it included new legislative requirements for certified home health agencies similar to those for nursing homes. Certified home health agencies had to meet minimum requirements for nursing and training standards for home health aides.

The regulations require on-site supervision of the home health aide by a registered nurse every two weeks if the patient is receiving skilled

nursing care (42 C.F.R. 484.36(d)). If another skilled service is being provided, an appropriate professional must make the supervisory visit. If the patient is not receiving skilled nursing services, physical or occupational therapy, or speech–language pathology services, the RN must make a supervisory visit at least every 62 days at a time when the aide is providing patient care.

Home health agency certification for Medicaid payment is linked to Medicare certification. Most states further link Medicaid with Medicare home health agency services through their state licensing statutes and regulations. A survey of states found that 10 states did not license home health agencies but used Medicare certification in 1999. Forty states and the District of Columbia have their own licensing laws for home health agencies (Harrington et al., 2000e) and their own regulations.

According to the Social Security Act (42 U.S.C. 1396d, Section 1905(a)(24)), personal care services (e.g., assisting people with activities of daily living such as eating and bathing) are those services “provided by an individual who is qualified to provide such services.” States are allowed to designate qualified organizational providers which may include certified home health agencies or agencies that are neither licensed nor certified. Certified Medicare and Medicaid home health agencies are not required to provide personal care services, but they may choose to do so. Independent workers, usually known as personal care attendants, may also provide personal care services. The duties of home health aides and personal care attendants overlap in that both are allowed to provide direct care to clients, such as help with bathing, dressing, toileting, and eating (Harrington et al., 2000d,e).

Home Health Agency Staffing Levels

The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that there were 745,600 home health care employees in 1998. There were also about 130,000 RNs working in home health care or about 6 percent of the national pool of RNs (BLS, 2000). Skilled nursing, home health assistance, and therapy services are the major home health services provided, but little is known about the amount and type of services provided by certified and uncertified home health agencies. Likewise, little is known about the contribution of medical directors, physicians, and nurse practitioners in home health agencies.

Home health agency personnel are critical, yet little is known about the quality of care they provide. The monitoring of personnel by HCFA has been limited because overall enforcement of quality standards in home health agencies has been extremely limited (GAO, 1997b). The committee believes that HCFA should increase its monitoring of home health staff including their education, knowledge, and competency, particularly for diverse population

groups such as ventilator-dependent individuals and children with severe disabilities. At the same time, new research efforts are needed to develop uniform standards for the qualifications of home health care personnel and ways to improve quality of care for nursing, therapy, and medical services.

Home health agencies are not required to appoint a medical director, although many have established formal and informal relationships with the medical community. No required visit schedule exists, but patients receiving home health services usually are seen by their physicians in an office setting.

Education and Training of Home Health Agency Staff

Certified agencies must have a qualified administrator who is either a physician, a registered nurse, or a health administrator with education and training and at least one year of supervisory experience. The Medicare conditions of participation for home health agencies (42 C.F.R. 484.36) also specify the training of home health aides to provide personal care services. The training generally covers the same areas described above for nursing assistants in nursing homes. The training must be provided through classroom and supervised practical training totaling at least 75 hours, with at least 16 hours devoted to supervised practical training (42 C.F.R. 484.36(a)). The person being trained must complete at least 16 hours of classroom training before beginning the supervised practical training.

Supervised practical training means training in a laboratory or other setting in which the trainee demonstrates knowledge while performing tasks on an individual under the direct supervision of a registered nurse or licensed professional nurse. The regulations also require 12 hours of in-service training for home health aides during each 12-month period (42 C.F.R. 484.36(b)(2)). The competency evaluation must address each of the subjects listed in the training program, and every home health agency must complete a performance review of each home health aide no less frequently than every 12 months.

Medicare specifies that the initial training of home health aides must be performed by or under the general supervision of a registered nurse who possesses a minimum of two years of nursing experience, at least one year of which must be in the provision of home health care. Other individuals may provide instruction under the supervision of such a nurse. The regulations also specify that the competency evaluation must be performed by a registered nurse (42 C.F.R. 484.36(b)(3)). The in-service training generally must be supervised by an RN who possesses a minimum of two years of nursing experience, at least one year of which must be in the provision of home health care.

States may have additional training requirements for home health

workers, and the extent of these requirements varies considerably (Scala and Mayberry, 1997). A recent study found that California and Illinois both required 120 hours of home health aide training, New Hampshire required 100 hours, Kansas and New Jersey required 90 hours, and Texas required 80 hours (Harrington et al., 2000e). The United Hospital Fund of New York (1994) suggested increased training to improve the quality of home healthcare. It recommended three weeks of training at a minimum for home health aides after two weeks of classroom work and demonstration of competence in required skills. In addition, it recommended special training and support for home health aides who manage difficult-to-serve clients, such as those with Alzheimer's disease or AIDS.

The federal training requirements may also need updating. The training should ensure the skills necessary to provide high quality of care, promote autonomy, and monitor changes in patients' conditions. In addition to general competencies, home health aides should be trained and tested to ensure they can provide appropriate care when they are working with special populations such as demented clients, children, individuals with AIDS, and other groups.

Concern has been expressed by the community of people with disabilities needing long-term personal attendant services that Federal Medicare and Medicaid training requirements do not include instruction for providing consumer-directed services. For example, Scala and Mayberry (1997) have argued that the lack of adequate training and information for both consumers and staff is a major barrier to consumer-directed programs. A study of consumer-directed home and community-based services conducted by the National Council on the Aging also identified such training as a major issue (Cameron, 1996).

HOME CARE

As noted in the previous sections, the home care work force includes workers in home health and home care agencies, including personal care agencies, and those workers who are independent care providers. All of the problems with the home health care work force are also seen in home care, but very few studies have examined home care personnel issues and their relationship to quality. Most of the literature is on access to, and satisfaction with, consumer-directed models of personal care service discussed in earlier chapters. In these models, consumers select, train, and supervise personal care workers (DeJong et al., 1992; Fenton et al., 1997; Scala and Mayberry, 1997).

Benjamin (1998) conducted a study of California's personal care services program and examined the differences between agency model services and independent providers with client-directed care. The study