6

A Research Agenda for Non-Heart-Beating Organ and Tissue Donation

Recommendation 7: Data collection and research should be undertaken to evaluate the impact of non-heart-beating donation on families, care providers, and the public. Further information on the burdens and benefits of this approach to donation needs to be gathered and assessed in a systematic, coordinated way. Further data are needed on (1) patient, family, provider, and public attitudes and concerns, (2) the costs of non-heart-beating donation, and (3) the outcomes from non-heart-beating transplantation. An ongoing, centralized data base of published studies would assist greatly in monitoring developments in non-heart-beating transplantation practices, costs and outcomes.

During the course of this study, it became apparent that many empirical questions about non-heart-beating organ donation and transplantation remain open. The committee identified several concerns that should be addressed through further data collection and research, and the systematic coordination and communication of findings.

RESEARCH PRIORITIES

The questions that arose during the workshop and committee deliberations clustered around two main areas of concern: first, the impact of non-heart-beating organ donation on the patients who become donors and on their families; second, the impact of non-heart-beating organ transplantation on transplant outcomes. The committee and the workshop participants identified the following areas in which additional information is needed to guide further development in non-heart-beating organ donation and transplantation practice.

Questions About Donation

-

What further data are necessary in order to develop consensus on the declaration of death following the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment and the cessation of cardiopulmonary function?

-

How can these data be collected in ways that are scientifically reliable but noninvasive and sensitive to donor patients and their families?

-

How do families respond to non-heart-beating donation? Anecdotal evidence supports the conclusion that some patients and families pursue this option eagerly and are profoundly disappointed if it cannot take place. However, there are no studies that compare the experiences of non-heart-beating donor families with those who choose not to donate in this way or with those who donate following death by neurological criteria.

-

What impact do the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment and rapid organ recovery have on family leave-taking and on subsequent coping with grief and loss?

Questions About Transplantation

-

What impact will non-heart-beating organ donation have on the shortage of organs for transplantation? Suggestions that organs from non-heart-beating donors can increase the supply of organs by as much as 20% (D’Alessandro et al., 1995; Koogler and Costarino, 1998; Lewis and Valerius, 1999) are balanced by suggestions that non-heart-beating donation may compromise public trust and thus reduce overall donation rates (anecdotal). With a total of approximately 150 non-heart-beating donors comprising less than 1% of donors in the past two years, the actual impact on organ donation cannot yet be assessed.

-

How much more costly is the recovery of organs and tissues from non-heart-beating donors than the recovery of organs and tissues following death by neurological criteria (Jacobbi et al., 1997; Butterworth et al., 1997)? Why are the costs higher, and what might be done to offset these higher costs?

-

Are the data on the outcomes of transplantation with organs from non-heart-beating donors adequate to persuade Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs) and transplant surgeons of the value of non-heart-beating donor organs? In spite of published reports of favorable outcomes following non-heart-beating organ transplantation (Yong et al., 1998), workshop participants reported continuing reluctance to use these organs due to concerns about quality and long-term transplantation outcomes. This reluctance stems from the limitations in the published data: small numbers and many confounding variables.

-

How do different ways of handling recovered organs affect organ viability and transplant outcomes? Surgeons and OPOs employ a number of methods to promote organ viability and good transplant outcomes. These methods include in situ cold preservation, the use of anticoagulants and vasodilators, and “pumping” kidneys following removal. As suggested during the workshop, these

-

interventions rely on clinical judgment and experience and on limited outcome studies. Experience with non-heart-beating organ transplantation is not yet extensive enough to allow for controlled trials of different organ-handling techniques and their impact on organ viability.

The committee identified two limitations to the data currently available on non-heart-beating organ transplantation. First, the studies involve small numbers of cases over limited periods of time. Second, the data have not been gathered into one easily accessible data base. Individual institutions or practitioners may not find the studies convincing enough, or readily accessible enough, to justify major innovations in practice.

The sponsor and the committee identified the need for a comprehensive strategy for evaluating the impact of non-heart-beating organ donation protocols. Designing such a strategy involves identifying the outcomes to be assessed, the variables to be measured in order to assess these outcomes, and the data to be collected in order to measure these variables. The committee commissioned an expert paper to propose a strategy for evaluating the outcomes of non-heart-beating organ transplantation practices and protocols. This paper is included in full in the following section as a resource for practitioners, institutions, government agencies, and other interested parties to use in designing future research on non-heart-beating organ transplantation.

MAXIMIZING BENEFITS, MINIMIZING HARMS: A NATIONAL RESEARCH AGENDA TO ASSESS THE IMPACT OF NON-HEART-BEATING ORGAN DONATION

Mildred Z. Solomon, Ed.D.

Education Development Center, Inc.

Introduction and Overview

This paper has been commissioned by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Non-Heart-Beating Organ Transplantation to propose a method for evaluating the dissemination and effectiveness of the recommendations from the two IOM reports on this subject. As with any evaluation effort, the first step is to determine appropriate purposes for the inquiry. One primary purpose and two related, secondary purposes are as follows:

-

The primary purpose of such an evaluation is to assess the potential benefits and potential harms of non-heart-beating organ donation to four key stakeholder groups: patients (i.e., prospective non-heart-beating donors and recipients), donor families, the health care system, and society or more precisely to underlying normative values that American society and American medicine have traditionally identified as important.

-

A second, related purpose is to compare the ways in which locally developed non-heart-beating donor protocols are being implemented in practice, with respect to both the OPOs’ and hospitals’ stated ideals, as expressed in their local protocols, and to the recommendations contained in both this report and the 1997 IOM report (IOM, 1997b).

-

A third purpose is to identify barriers to the development of non-heart-beating donation protocols and to design and test interventions to enhance non-heart-beating donation in ways that minimize potential harms, while maximizing potential benefits, to donor families and to organ recipients.

These three purposes are fundamental to the arguments and recommendations made in this paper and define the scope of the evaluation suggestions that are presented.

To accomplish these purposes, this paper seeks to answer the following questions:

-

What are the potential harms and benefits of non-heart-beating organ donation to patients, families, the health care system, and society at large that can and ought to be monitored?

-

What is a feasible and effective research agenda for assessing the impact of non-heart-beating organ donation on these four key stakeholder groups? In other words, what key research questions ought to guide inquiry, and what kinds of empirical evidence would it be appropriate to collect in order to monitor the implementation and impact of local non-heart-beating donation policies?

-

Within each of the research priority areas identified, what are some recommended data collection strategies and related methodological considerations?

To answer the first question, a conceptual framework is presented in Table 6-1. This framework lays out an a priori set of potential harms and benefits. This framework is used to guide the development of a research agenda. Key research questions, data collection strategies, and special methodological considerations are described for each of three recommended research priorities:

-

research on family perspectives aimed at understanding the consequences for, and experiential realities of, families who have consented to non-heart-beating donation;

-

development of a “profile” of institutional behaviors to ascertain the extent to which local policies and IOM recommendations are being implemented in practice in health care settings; and

-

development and testing of interventions capable of enhancing non-heart-beating donation policies, so that potential family benefits may be maximized.

The final two sections of this paper describe the limitations of such a plan as well as the expected benefits.

Potential Harms and Benefits and Their Implications for Evaluation Research

Table 6-1 presents a detailed list of possible harms and benefits of non-heart-beating donation for each of the four key stakeholder groups: (1) patients who may be prospective donors, (2) families, (3) the health care system, and (4) society. The list was derived deductively by reviewing harms and safeguards described in the 1997 IOM report (IOM, 1997b) and other published literature (e.g., Arnold, et al., 1995; Koogler and Costarino, 1998) and from the author’s professional experience working to improve end-of-life care in U.S. hospitals (Solomon, 1995; Solomon et al., 1991). The list therefore represents an a priori set of possible harms and benefits that can and should be modified on the basis of empirical evidence. If the research proposed later in this chapter is conducted at OPOs and hospitals, it will create an opportunity to confirm or disconfirm these issues and to discover other themes that have not yet been raised.

Table 6-1 is organized by stakeholder group. The middle column, “Possible Mechanisms” suggests the ways in which potential harms might come about. Since the potential benefits are more straightforward, it is not necessary to list possible mechanisms for them.

In addition to looking in detail at stakeholder groups, it is helpful to identify major themes. The following sections describe five themes that evaluation efforts should seek to address.

Greater Patient and Family Choice, Enhanced Psychosocial Outcomes for Families, More Organs

Protocols that allow non-heart-beating donation serve several purposes. Non-heart-beating donation is intended to uphold patient autonomy (in cases where patients have clearly indicated a wish to become organ donors and communicated this intention prior to losing their decision-making capacity) and to honor family requests to donate. Evaluation research should determine the extent to which patients and families initiate such requests on their own. In addition, after families have decided to withdraw treatment and allow their loved one to die, trained OPO requesters may approach the family to discuss non-heart-beating donation. Thus, data can and should be collected on the number of cases, by hospital and OPO, in which a trained requester has initiated a donation request to a family after the decision to terminate treatment was made and on the number of families consenting to such staff-initiated donation requests.

There may be positive psychosocial consequences for families that will be important to document. In traditional donation, where death was established by neurological criteria, families have reported that donation helped give meaning to their tragic, senseless loss (Bartucci, 1987; Coolican, 1994; Riley, 1999). It is

TABLE 6-1 Potential Harms and Benefits to Key Stakeholder Groups

|

|

Potential Harms |

Possible Mechanisms |

Potential Benefits |

|

Patients |

Patients could be prematurely “objectified”( i.e., perceived as donors rather than as persons) |

Interest in donation could unconsciously lead to premature determinations of futility |

|

|

|

Death could be hastened |

|

|

|

|

Having an invasive procedure done while still able to perceive it |

Cannulation without analgesia in certain patients |

|

|

|

Inadequate pain management and/or sedation |

Clinician worries about medication might cause physiological abnormalities that compromise organ quality |

|

|

|

Wishes to donate could be ignored |

Protocols that do not allow non-heart-beating donations or discourage such donations |

Patients’ satisfaction that their wishes, if expressed, would be honored |

|

|

Patients could be “abandoned” by their caregiving team |

Staff discomfort with death, dying, and/or organ donation |

|

|

Families |

Frustration and anger if wishes to donate are not honored |

Protocols that do not allow non-heart-beating donations or that discourage such donations |

Satisfaction that wishes have been honored |

|

|

Guilt that they have overridden loved one’s explicit advance directives, indicating the patient had a desire to donate |

|

Comfort in the knowledge that a loved one’s gift has extended life for someone else |

|

|

Guilt if they feel that they have agreed to organ donation but are not sure it was the right thing to do or what the loved one would have wanted |

|

|

|

|

Guilt or depression if they feel they have hastened death in order to donate |

|

|

|

|

Misunderstanding or confusion about the differences between withdrawing treatment, assisting suicide, and euthanasia |

|

|

|

|

Inadequate opportunities to say farewell, disruption, sense of abandonment, or lack of closure |

Need to remove deceased to operating room for organ retrieval |

|

|

|

Possible negative impact on bereavement |

|

Possible positive impact on bereavement |

|

|

Financial burdens |

If procedures that would have been forgone are instituted to maintain organ quality |

|

|

|

Potential Harms |

Possible Mechanisms |

Potential Benefits |

|

Families |

Distrust of the health care system and of health care professionals |

|

Sense of support and satisfaction with health care institution and health care professionals |

|

Health Care System |

Greater distrust between the public and the health care system |

If requests for organ donation are made at the same time as decisions to forgo treatment |

More trust |

|

|

Public backlash, resulting in fewer donations |

|

Greater pool of donors and more donations |

|

|

Costs might exceed benefits |

|

|

|

Society |

Slippery slope from request and consent to persuasion to coercion |

|

|

|

|

Intentional or unintentional objectification of patients as potential donors rather than persons |

|

Greater respect for diversity of views about organ donation, including support for informed dissent |

reasonable to infer that families of non-heart-beating donors would also find psychological and spiritual comfort in their decision to donate. Evaluation research should seek to determine the impact of consent to non-heart-beating donation on the psychological well-being of the family.

Non-heart-beating donation protocols are a hoped-for means of increasing the national supply of organs from a large, untapped source of potential donors. Thus, evaluation research should focus on determining the extent to which non-heart-beating donation does, in fact, increase the supply of organs, and what the viability of these retrieved organs is, including the effect of their transplantation on the survivability of recipients.

Better End-of-Life Care

There are also possible collateral benefits to the health care system of allowing non-heart-beating donation. To be effective, such protocols will have to involve training health care professionals in the communication skills necessary for conveying a grave prognosis and for supporting patients and families through the final phase of life. It will also be essential to enhance clinicians’ understanding of what is, and is not, ethically and legally permissible regarding the use or withdrawal of life-sustaining medical interventions (Solomon, 1993). Otherwise, families will not be able to arrive at well-informed decisions about the use of life supports and may become confused or distrustful. If OPOs and hospitals take these educational challenges seriously, they should intensify their educational efforts to improve staff skills in communication and ethical analysis. Thus, a possible collateral benefit of non-heart-beating donation might be an increased capacity on the part of health care providers to support well-informed family decision making near the end of life. Evaluation tools could be developed to ascertain improvements in the clinical staff’s comfort in discussing a grave prognosis with families, staff understanding of key ethical concepts necessary to help families make decisions about forgoing life support, and staff comfort discussing death, dying, and organ donation.

Finally, there may also be broad, societal benefits, such as the cultivation of greater altruism among the public and greater societal openness toward dying, death, and organ donation. For example, making non-heart-beating donation permissible and available might help patients, families, and health care professionals to see organ donation as one final decision on a single continuum of end-of-life care choices that all families should discuss and anticipate together.

Impact on the Public’s Trust

A major potential burden of moving to non-heart-beating donation is a possible erosion in public trust in the organ procurement system (Burdick, 1995). Distrust might arise if families or patients began to sense that less than every-

thing was done to ensure the patient’s recovery. This concern pertains to all types of organ donation; therefore, there has been a longstanding commitment to maintaining separation between the clinical team that cares for the patient and the clinical team that manages organ procurement.

Ideally, this division of clinical teams maintains the separation between patient interests and organ procurement interests. In practice, however, this distinction is less clear, and there are ways in which conflicts of interest may emerge. For example, clinicians caring for patients are the ones who alert organ procurement organizations that their patients may be approaching brain death and may therefore be appropriate as potential donors. Secondly, there may be strong incentives in health care institutions specializing in transplantation that could privilege organ procurement interests over patient interests. Moreover, the general social context, both within health care institutions and among the general public, is highly supportive of organ donation and transplantation, which may exert conscious or unconscious pressures on patients and their families.

However, non-heart-beating donation complicates this picture even further. Determinations of “futility” and “hopelessness” are vaguer than the relatively “purer” and more clinically straightforward determination of “brain death” (Shaw, 1995). Therefore, all non-heart-beating donation policies insist that the decision to withdraw treatment must be made independently of and prior to the decision to donate. Health care professionals should not initiate discussion of the topic, until after patients or family members have decided to terminate treatment.1 Of course, families may raise the question of organ donation at any time while in the midst of grappling with their loved one’s grave condition, and if they do, health care professionals will have to respond—hopefully by validating family concerns and interests, yet helping them to see the importance of focusing first on deciding whether to continue or withdraw further life-sustaining treatments, based on their loved one’s wishes and best interests.2

Thus, a key mandate of any evaluation effort must be to collect data on the extent to which the line was maintained between the decision to withdraw treatment and the decision to donate organs. However, as Shaw (1995, p. 103) points out, “The first time the issue of conflict of interest arises is not in contemplating the withdrawal of care, but in judging that the prospective donor’s condition is ‘hopeless.’ ” This issue is particularly problematic if physicians and nurses caring for a gravely ill patient know of a prospective recipient who is in dire need

and could directly benefit from the apparently dying person’s organs, or in hospitals where a large amount of transplant surgery takes place and there may be cultural and financial incentives that support strong prodonation attitudes among the staff. Thus, in addition to determining whether separation existed between the decision to withdraw treatment and the decision to donate organs, evaluation efforts should seek to confirm that the prognosis of hopelessness was in fact accurate, that the best possible care was given to such patients, and that the prospect of organ donation did not influence treatment decisions. These constructs are difficult to measure, but they are central to establishing public trust.

Impact on the Quality of the Dying Experience for Patients and Families

In the case of organ procurement following death determined by neurological criteria, the declaration of brain death creates a sharp line between patient treatment and organ procurement. Patient treatment is pursued until a neurological determination of death has been made. Management of the donor then shifts to organ procurement, but any alterations in management do not adversely affect the patient because death has already occurred. Moreover, since such donors are being maintained by artificial means, the family has ample opportunity for leave-taking at their own pace in the intensive care unit before the donor is removed to the operating room, where artificial support will continue throughout the organ procurement process.

Quite the opposite case occurs in non-heart-beating donation. In organ donation following death established by cardiopulmonary criteria, medications and procedures necessary for maintaining organ quality may be administered before death without benefit to the patient. Also, in some circumstances, there might be an inclination to limit medications (morphine or sedatives) that could ease the dying process for fear these medications might create “physiological abnormalities that could jeopardize the functional quality of potential donor organs (Shaw, 1995, p. 106).” Furthermore, the time between withdrawal of life support and organ procurement must be minimized to avoid organ damage, with donors often going immediately to the operating room where life support can be discontinued and organ procurement initiated immediately. These alterations in patient management raise concerns about eroding the quality of the dying experience and, in particular, about diminishing the family’s opportunity for farewells (Fox, 1995, IOM 1997b). Some commentators (Frader N., 1995; Koogler and Costarino, 1998) have also pointed out that removal of the patient to the operating room for termination of life support may be especially disturbing in pediatric cases, since families often request—and pediatric intensivists and critical care nurses usually offer—an opportunity for parents to hold their children as life support is withdrawn. In the case of non-heart-beating donation, families may have to choose between organ donation and holding their dying child.

In sum, then, there is an underlying irony. Non-heart-beating donors are, by definition, individuals who have chosen, or whose families have chosen, to forgo life-sustaining treatments, often because they want a lower-“tech” death and more opportunities for what the public and lay media have called “a good death.” Yet, in non-heart-beating donating, the family’s altruism may result in a more technologically invasive death than the family understands.

Several obligations follow from this fact. First, there are obligations to disclose how the patient’s care will change as a result of the decision to donate. Many families will still make the choice to donate, but there is an ethical imperative to disclose the trade-off. Secondly, hospitals and OPOs should recognize this irony and strive to create the most family-supportive environment possible during the final hours and moments of their loved one’s life. Special arrangements should be developed to enhance family privacy and leave-taking. Evaluation studies should document these innovations and study their impact on family satisfaction with the dying experience.

Consequences for Families After the Death of Their Loved One

Making the decision to withdraw life-sustaining treatments is undoubtedly a difficult one for families, yet there is virtually no research on how families cope with this responsibility. From anecdotal experience and personal testimonials, however, it seems that many patients are confused about the differences between withdrawing treatments and assisting suicide, and some families may feel guilt or remorse about not having done all that could be done. These feelings might be compounded if families worried retrospectively that they had been unduly influenced to terminate life support by pressures (either internally or externally imposed) to donate their loved one’s organs. It is therefore important to develop ways to measure guilt, remorse, depression, and grief reactions among family members several months, or even years, after the death of their loved one.

Another key issue to explore, both with families directly and through review of hospital billing procedures, is the extent to which decisions to donate their loved one’s organs may result in additional financial burdens for families. Grossman et al. (1996, p. 1831) found that the average terminal hospital stay for a donor who had been declared dead by neurological criteria was $33,997—of this amount, $17,385 was for care that one would consider “futile” for the patient but “necessary for improved organ procurement rates.” Although these estimates were based on donors who had died by neurological criteria, there will surely also be costs for families opting for non-heart-beating-donation. OPOs may pay the costs associated with organ procurement, but they usually only begin to pay for costs incurred after the determination of death has been made by neurological criteria (Grossman et al., 1996). The situation may be exacerbated in the non-heart-beating donation scenario, where it may be even more difficult to determine when the family’s responsibilities for costs should end and the OPO’s begin. Empirical re-

search is essential to ensure that the altruistic decision to donate does not mean that families are paying a higher overall hospital bill than would otherwise have been the case if life supports were simply withdrawn or never instituted.

In the next section, a national research agenda is proposed that is capable of monitoring the extent to which these potential harms are being minimized, and the potential benefits maximized, in hospitals and OPOs employing non-heart-beating donation protocols.

A Research Agenda in Three Parts

Box 6-1 presents eight research questions that ought to drive the evaluation research agenda. The first question, What impact, if any, has non-heart-beating

|

BOX 6-1 Proposed Research Questions

|

donation had on the public’s trust in physicians, hospitals, and the nation’s organ procurement system? is a superordinate question, in the sense that the answers to it must be derived from answers to several of the following questions. For example, by learning about the impact of non-heart-beating donation on the wellbeing of patients and families (question 2), by studying the extent to which local non-heart-beating donor protocols safeguard conflicts of interest (question 3), and by ascertaining the total number of organs retrieved from both non-heart-beating donors and donors who have been declared dead by neurological criteria (question 6a) during the same time period, researchers and policy makers can infer whether non-heart-beating donation is being implemented in ways that have enhanced or diminished public trust and family willingness to donate.

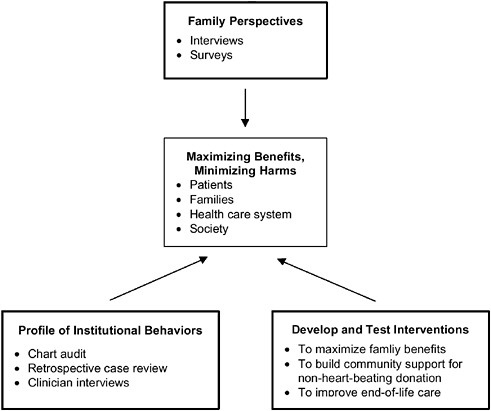

Three main types of research activities would be capable of answering seven of these eight questions. (Although question 8, pertaining to costs, is an essential one, this paper does not address the mechanisms for evaluating costs, because the issue is complex and goes well beyond its scope) The three main research activities are the following:

-

conducting research on family perspectives aimed at understanding the consequences for, and experiential realities of, families who have consented to non-heart-beating donation;

-

developing a “profile of institutional behaviors” that would include a variety of measures capable of capturing the extent to which the 1997 IOM recommendations (IOM, 1997a) and local non-heart-beating donation policies are being implemented in practice in health care settings; and

-

developing and testing interventions capable of enhancing non-heart-beating donation policies so that potential benefits may be maximized.

Figure 6-1 is a pictorial representation of the relationship among these three research priorities. As the figure indicates, the agenda is “triangulated” in the sense that when taken together, all three basic types of research activities would provide significant information on the extent to which non-heart-beating donation protocols are, in fact, minimizing harms and maximizing benefits for all the key stakeholders, as well as data on how these protocols could be improved. In the remainder of this section, relevant measures, data collection methods, and special methodological considerations are proposed for each of these three research priorities.

Research on Family Perspectives

The main reason for conducting research on family perspectives is to ascertain what the impacts of non-heart-beating donation protocols, and family decisions to donate or not, have been on patient and family well-being. Qualitative interviews will be an essential aspect of this research, because the goal is

FIGURE 6-1 National research agenda for assessing the impact of non-heart-beating organ donation.

to try to learn about a family’s experience with their loved one’s end-of-life care; the family’s interpretation of events leading up to the donation request; and the meaning the family made of its decision, both during its deliberations and afterwards. However, surveys could be used to confirm qualitative findings in a larger, national sample of families, after prior qualitative studies had been conducted.

Timing for the interviews and/or surveys is important. Many hospitals conduct bereavement calls to families several weeks or months after the death of a loved one. It might be possible to “piggyback” questions onto these interviews. Prior research on how to optimize the donation request process (DeJong et al. 1998; Franz et al., 1997) found that it was feasible and effective to contact the families of donors who had been declared dead by neurological criteria six months after the death of their loved ones. Closed-ended questions asked via telephone interview yielded important information about how to improve the donation request process.

|

BOX 6-2 Types of Family Data to Collect

|

Ideally, surveys and interviews with family members must collect data from both families who have consented to donate and those who have not. This design in the sampling plan is important, because otherwise it will be hard to tell to what extent any reported negative family consequences are a result of the donation decision itself or simply a consequence of inadequate care near the end of life.

Furthermore, collecting data on a broad and diverse family population is particularly important, because family perspectives vary greatly across different ethnic groups on a whole range of related issues, including death, dying, organ donation, and advance care planning (Ersek et al., 1998), as well as trust in the health care system (Dula, 1994) and attitudes toward health care decision making (Blackhall et al., 1995; Koenig, 1997; Solomon, 1997).

Box 6-2 presents eight issues that family interviews and/or surveys should explore. These include probing for (1) evidence that families were involved in decisions about the use of life support and in setting goals of care for their loved one; (2) the family’s knowledge of the patient’s wishes and/or reasons the family felt that withdrawal of life support was in the patient’s best interest; (3) evidence of separation between the decision to forgo life support and the decision to donate; (4) satisfaction with the donation request process; (5) satisfaction with the care the family and loved one received, (e.g., optimal pain management, ample opportunities for family leave-taking); (6) retrospective satisfaction with whatever decision the family made; (7) specific psychosocial consequences, such as possible guilt, remorse, or evidence of abnormal grief reactions; and (8) financial burdens on the family.

Developing Profiles of Institutional Behavior

In addition to proposing ways to safeguard potential and perceived conflicts of interest, the 1997 IOM report (IOM, 1997a) recommended case-by-case analysis by an attending physician (who is not a member of the organ procurement team) to determine whether or not anticoagulants and vasodilators (used to enhance organ preservation) might safely be used in patients whose families have consented to non-heart-beating donation. The report also called for family consent for premortem cannulation (insertion of a femoral arterial line for injection of preserving fluids postmortem). Rather than having to withdraw treatment in the operating room, away from families, premortem insertion of these cannulae makes it possible for life support to be withdrawn in the intensive care unit, where families can say their farewells. However, cannulation is an invasive procedure, and in a conscious person, insertion of the cannulae is painful and requires analgesia. The report also recommended a uniform method for determining death in controlled non-heart-beating donation (cessation of cardiopulmonary function for at least five minutes as measured by electrocardiographic and arterial pressure monitoring).

A combination of three different data collection strategies would result in a summarizable profile of the extent to which OPOs and hospitals have moved in these directions. Chart reviews could be done to determine evidence of family involvement in decision making and in setting goals of care. Data should be collected on the severity of the prognosis and the reasons that patients (if conscious) and their families felt life support was no longer appropriate. If good documentation practices have been instituted, the chart should also provide evidence of (1) a separate discussions of the decision to forgo treatment and the decision to donate; (2) whether an attending physician, unrelated to the organ procurement team, analyzed the suitability of anticoagulants and vasodilators for the patient and whether these were ordered (for a random, subsample of charts, there could also be an expert review to determine whether anticoagulants and vasodilators were ordered in cases where they should have been contraindicated); and (3 ) whether family consent was sought prior to premortem cannulation.

Unfortunately, data from charts are often incomplete and sometimes unreliable, so other ways to document compliance with these recommendations may have to be developed.

As part of an exit interview or at the end of the family interviews, families could be asked whether key items, such as premortem cannulation, had been explained to them and whether their consent had been sought for that procedure. Family responses could be compared to results on an identical checklist, which a health care professional on the clinical team would be expected to fill out for all non-heart-beating donors. In this way, it would be possible to compare clinicians’ views of what they have communicated to families with families’ views

of what they were told. Negative findings from the families may indicate either that the health care team failed to disclose these issues or that families failed to “hear” them; in either case, knowing that the communication failed is important for improving disclosure and consent procedures in the future.

Retrospective case review is another method that hospitals and OPOs could use to monitor compliance with their own non-heart-beating donor protocols and/or the recommendations of the 1997 IOM report. McNamara et al. (1999) have found this to be an effective method for monitoring compliance with protocols for neurological determination of death. Case review of non-heart-beating donations would make even more sense because of the potential conflicts of interest that one wants to monitor. Derived from the quality assurance movement, retrospective review, performed on a routine schedule, allows staff to follow the “path” that individual cases have taken in order to better understand where there may have been “glitches” in the system and to improve case management so it can come more directly in line with the recommended protocol. For the purposes outlined here, it would be wise for reviews to be done on a subsample of all cases in which patients meet some explicit criteria of grave prognosis (perhaps a certain number of hours or days on ventilatory support), not just on a subsample of cases in which discussions about the withdrawal of life support have been initiated. Including this broad a net is important because one of the findings might be that in many cases, a grave prognosis, which should have triggered discussions about life support, never did result in conversations with patients (if they were capacitated) or with their families.

Clinician interviews should also be an integral part of the data collection strategies used to create a profile of institutional behaviors. In particular, intensivists and critical care nurses are key informants, whose views will be essential for understanding how non-heart-beating donation is working. Box 6-3 presents examples of seven issues that these interviews should explore: (1) clinicians’ perceptions of whether, and to what degree, families are involved in decision making and setting goals of care (which can be used in connection with a similar question that is asked of families); (2) perceptions of whether separation of the decision to forgo life support and the decision to donate has been maintained, and what barriers and importance (or lack thereof) clinicians see in maintaining this separation; (3) clinicians’ own satisfaction with the donation request process; (4) clinicians’ perceptions of families’ satisfaction with the donation request process; (5) clinicians’ satisfaction with the quality of the dying experience for patients and families; (6) clinicians’ perception or experience of conflicts of interest; and (7) concerns of conscience that clinicians may have regarding any aspect of the non-heart-beating donation or procurement process.

|

BOX 6-3 Types of Clinician Data to Collect

|

Developing and Testing Interventions to Maximize Family Benefits and Improve Non-Heart-Beating Donor Protocols

This category of research covers a broad range of possible intervention studies that could conceivably be undertaken. The research could focus on building community support for non-heart-beating protocols or on designing innovations to improve family experiences with non-heart-beating donation. For example, some institutions might want to explore ways to enhance family leave-taking and thereby address donor family concerns about high tech death. Special rituals or compromises in the timing of removal to the operating room might be explored and their impact on families (and organ viability) documented. Other institutions might want to explore ways to integrate their protocols with efforts to improve end-of-life care more generally for all patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). For example, as part of their involvement in the Decisions Near the End of Life program, Dowdy et al. (1998) increased attendings’ willingness to hold end-of-life conversations with families, generated greater documentation of the family’s values and preferences in the medical record, and decreased resource utilization in the ICU, when they established an institutional routine requiring a conversation about goals of care whenever any patient in the hospital’s ICU had been on a ventilator for 96 hours or more. The goal was to ensure that the attending would speak with the family (or patient, if he or she was able) about the understanding of the patient’s prognosis and then develop a mutually agreed upon goal for care that could include either continued ventilatory support, terminal weaning, or a variety of intermediate trials of treatment. The point was not to advocate any particular substantive decision, but simply to ensure that a conversation took place, that families were apprised of the kinds of issues

they were likely to face in the coming days, and that caregivers were made aware of family values and preferences. Interventions that build on these findings, and simultaneously take new non-heart-beating donation protocols into account, might enhance end-of-life care and increase organ donation as well.

Methodological Challenges

It is important to recognize that even if one conducts research on families (both consenting and nonconsenting) that have been approached with a donation request, there may be other families of potential non-heart-beating donors who were not approached and therefore will not fall within the group of people being studied. Since the clinical criteria for neurological determination of death are straightforward and usually recorded in the medical chart, death record reviews routinely done by OPOs, clearly establish which patients who had been declared dead by neurological criteria were candidates for donation and whether their families were approached, as they should have been. In the case of non-heart-beating donation, it remains an open question as to whether medical charts are a good means of identifying prospective candidates. Although the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) guidelines for routine referral and trained request are intended to notify the local OPO of all deaths and impending deaths, prognostic indicators are not yet well established, and providers may not always record (or sometimes even hold) end-of-life discussions about patient or family wishes to terminate treatment (Solomon, 1991). As a result, non-heart-beating donation researchers may be able to interview or survey only those families that were approached with a donation request, and it may therefore prove difficult to determine whether there are systematic biases in which families are approached with such requests.

It is important to determine these biases for a number of reasons. For example, Guadagnoli et al. (1999) found that the odds of the family of a white patient who had been declared dead by neurological criteria being approached for donation were nearly twice the odds that the family of an African-American patient would be approached. However, in other circumstances the opposite may be true: families of patients who are seen as socially undesirable or families of patients from ethnic groups that are different from those of their health care providers may be disproportionately approached. This may be particularly true for non-heart-beating donors. This may explain why some protocols, prior to the 1997 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report (IOM, 19997a) prohibited non-heart-beating donation unless it was explicitly requested by family members, not initiated by staff. Without being able to identify the universe of potential non-heart-beating donors, it will be extremely difficult to determine whether there are systematic biases in terms of who is being approached to provide a non-heart-beating donation.

Significance and Benefits of This Plan

To date, most of the empirical research in the field of organ donation has focused on identifying public attitudes to organ donation (Franz et al., 1995) and trying to understand how to improve the donation request process (e.g., DeJong et al., 1998; Franz et al., 1997; Gortmaker et al., 1998; McNamara and Beasley, 1997; Siminoff et al., 1995) and thereby enhance family consent rates. The purpose of the research being proposed here is very different. The primary goal of this evaluation plan is not to increase donation rates, but rather to inform families, policy makers, ethicists, health care organizations, OPOs, the transplant community, and the general public about the trustworthiness of non-heart-beating donation protocols. Thus, the intent of this research is neutral: to uncover potential harms and benefits for patients and their families, so that protocols can be implemented with confidence or be redesigned to address problems.

If this research agenda were adopted, individual health care institutions and OPOs would be able to (1) assess the degree to which their practices are in line with their own local policies and with the guidelines of both this and the 1997 IOM report; (2) monitor the impact of their policies on families; and (3) make improvements in their approach to non-heart-beating organ donation on the basis of empirical data.

Moreover, if a number of OPOs and health care institutions around the country agreed to collect the same kinds of data, it might be possible to (1) assess the extent of compliance nationally and regionally with the recommendations of these IOM reports, and (2) compare the impact of different kinds of policies on family well-being. Although the recommendations call for some degree of national uniformity on key points, by asking OPOs and hospitals to develop their own local protocols, there is a clear recognition that protocols will differ in various regions of the country. While diversity in certain aspects of these local protocols is to be expected and perhaps even encouraged, common agreement on the outcomes to be measured and the development and use of shared research tools would help create a national laboratory for cross-institution and cross-regional comparisons. Although numerous separate research studies can and should emerge from this plan, it would be wise to begin a national dialogue about what is worth measuring and how to go about doing so in coordinated ways that can yield the most powerful results for the broadest set of stakeholders.

Conclusion

The recommendations of this report address the study goals of (1) familiarizing relevant parties with the 1997 IOM report; (2) identifying obstacles to implementing its recommendations; (3) facilitating the development of organ procurement practices consistent with its principles and recommendations. Based on the input from the workshop, the committee recommends the development

and implementation of non-heart-beating donation protocols. This report provides guidelines for developing and implementing non-heart-beating donation protocols. These guidelines are based on the findings and recommendations of the 1997 IOM report and on the consensus and variations identified during the 1999 workshop.

In the course of the study and the workshop, the committee identified strong reasons for making the option of non-heart-beating donation available to all patients and families who want it. The committee recognized, however, that there are impediments and potential impediments to the acceptance of non-heart-beating by health care providers, organ procurement and transplant professionals, and the public. To the extent possible within this study, the committee sought strategies for addressing these impediments. It found that further research is needed to resolve many of the questions about non-heart-beating donation and transplantation that were identified during the study and at the workshop.

Dr. Solomon’s paper has been included in full because it highlights the many areas where further research is needed to evaluate the best approaches to non-heart-beating organ donation, procurement and transplantation. Active non-heart-beating donation programs have established protocols that satisfy the underlying ethical concerns of promoting benefit and avoiding harm, respecting patient and family choice and well-being, and avoiding conflicts of interest. Active programs have developed strategies for meeting patient and family needs at the end of life. Non-heart-beating donation under such protocols as these has great potential for providing options to patients and families, and for contributing to future developments in organ procurement and transplantation.

The findings and recommendations of this report will be disseminated to OPOs and transplant centers, to physician specialty groups, and to transplant and health care professional associations. The report is intended to serve as a resource for those who are involved in non-heart-beating donation or in program initiation and protocol development. It is intended also to provide information on the current state of knowledge about non-heart-beating donation and transplantation for those who are concerned about potential impediments. Further understanding of the benefits and impacts of non-heart-beating organ donation relies on further experience and research as outlined in this report.