2

Facility Acquisition Practices and Industry Trends

Reviewers tend to start out with an attitude of general superiority over the applicant. They then proceed immediately into critical “instructive” mode: looking for trouble, in other words, and being satisfied only with pointing out flaws, as opposed to working in a collaborative or respectful advocacy. An inflexible, ham-handed, or uneducated reviewer is the architect's chief nightmare and number one complaint concerning design review boards.Brenda Case Scheer, Associate Professor of Urban Planning, University of Cincinnati (Brown, 1995)

FACILITY ACQUISITION PROCESS

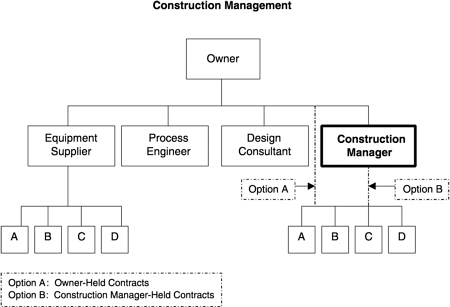

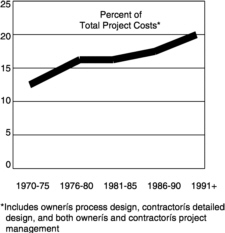

The process of acquiring a facility usually includes five phases that can be generalized as shown in Figure 2.1. The contracting method used will determine whether the five phases occur in sequence or if some phases occur concurrently. The contracting method can also effect who is involved at each phase (architect, engineer, construction contractor, etc.). For example, using the design-bid-build contract method, the five phases generally occur in sequence with the architect/engineer (A/E) involved in the design phase and a construction contractor in the construction phase. A design-build acquisition, in contrast, will use the same contractor for the design and construction phases, thus allowing some phases and activities to occur concurrently. Regardless of the contracting method used, the acquisition of a facility will necessarily involve activities and decisions related to conceptual planning, design, procurement, construction, and start-up. A more complete discussion on contract methods and the role of the owner in the review of designs is provided later in this chapter.

During the conceptual planning phase various feasibility studies are conducted to define the scope or statement of work based on the owner's expectations for facility performance, quality, cost, and schedule. Several alternative design solutions can be considered during this phase, leading up to the selection of a single preferred approach. The preferred approach may be a schematic that includes functional requirements such as square footage estimates for various functions and adjacencies or connections of functions that are desirable or required.

The design phase usually starts once the statement of work and preferred design approach have been developed. From the schematic, the design matures into final construction documents comprising the plans and specifications from which equipment procurement and construction bids can be solicited. Estimated facility cost and schedule issues receive increasingly intense review during the design phase so that the owner has a high level of confidence prior to bid that the performance, quality, cost, and schedule objectives defined during the conceptual planning phase can be met.

FIGURE 2.1 Generalized facility acquisition process.

Complex facility projects usually include a procurement phase in order to expedite the purchase, manufacture, and delivery of long-lead-time equipment such as unique process machinery, large electrical and mechanical equipment, and sophisticated architectural components. Such equipment procurement may proceed in parallel with construction phase activities, so that the owner ultimately is able to furnish long-lead-time equipment to the construction contractor in a timely manner, thus avoiding construction delays attributable to late equipment delivery.

Early in the construction phase a formal construction management plan is developed describing the intended sequence and method of construction activity as well as the relationships, responsibilities, and authorities of all involved parties (owner, user, A/E, construction contractor, speciality contractors, and relevant consultants). The biggest challenge during the construction phase is managing changes resulting from such sources as scope of work changes by the owner, errors and omissions in the construction documents, and unknown or changed site conditions. The construction phase is considered complete when the owner accepts occupancy of the facility, although final completion of construction may continue for months (or even years) until identification and resolution of all discrepancies are mutually agreed upon.

The start-up phase, sometimes called commissioning, begins with occupancy of the facility by its user. Building components are tested individually and then in system with other components in order to measure and compare their performance against the original design criteria. Facility operation and maintenance plans are implemented, tested, and refined as appropriate.

A BRIEF HISTORY

During a 1995 seminar sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts, Robert A. Peck (deputy director, Federal Communications Commission) and David M. Childs (senior partner, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill) spoke of the early days of federal building design and construction. Mr. Peck noted that from the early 1800s through the 1930s, most federal structures were designed by in-house design organizations. Mr. Childs agreed, noting that this period saw unusual excellence in civic buildings during three separate stages:

The planning and design of Washington DC, the federal city that was to house the great buildings of the American Democracy, is one example. The great city halls and courthouses of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—ennobling buildings that were conceived and built when American society lacked the resources it now has—are another. The integration of art, craft, and architecture that characterized the great federal projects of the Works Project Administration (WPA) represents a third pinnacle of accomplishment (Brown, 1995).

Thanks in no small part to those early investments of the Works Project Administration, America's private sector design and construction industry has grown tremendously since the 1930s. As more and more design capability became available within the private sector, government agencies increasingly contracted with them for support services.

The 1980s will be remembered as the period when American society and its business institutions were undergoing what President Carter described as “a great malaise.” American business competitiveness seemed to have hit a ceiling above which it could not climb, the economy was in a slump, and the American reputation for innovation and productivity had shifted elsewhere, primarily to Japan. Stung by such competitive failure, America's businesses began to search out and embrace fundamental changes to their business processes. New management theories and processes were tried including Results-Oriented Management, Management by Objective, Total Quality Management, The Deming Principles, and ISO-9000, an international standard. American business also explored the potential for enhancing productivity offered by an accelerating revolution in technology—particularly in the areas of information technology and communications. The result is history as the United States has retaken its world leadership role in business and manufacturing innovation, efficiency, effectiveness, and competitiveness.

Within the design and construction industries, productivity increases have resulted from a number of drivers including:

-

New management practices that rely on collaborative processes for problem solving and which emphasize teamwork: close and constant participation by all interested parties, with a focus on aligning these parties to common objectives with mutually beneficial solutions.

-

Technology advances such as computers, computer-aided design software, cell phones, and fax machines that have transformed both design and construction management efficiency and effectiveness.

-

New construction equipment, especially for materials handling.

-

Increasing mechanization of construction tasks.

-

New products and systems incorporated into built facilities.

DOWNSIZING OF FACILITY ENGINEERING ORGANIZATIONS

This period of change has been particularly pronounced with regard to how corporate and government owners manage the acquisition of facilities and other projects. As noted by The Business Roundtable in a 1997 white paper,

Virtually all major firms have reduced the size and scope of work performed by engineering organizations. Many firms are drifting because they are uncertain about the appropriate size and role of their in-house capital projects organization. Nearly every owner's engineering and project management organization in the US has been reorganized, sometimes repeatedly, without achieving a satisfactory result in many cases (TBR, 1997).

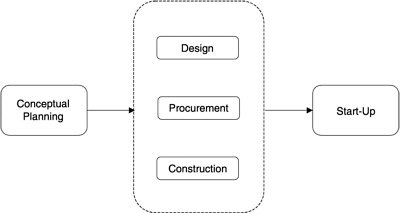

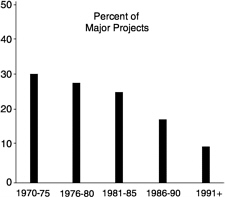

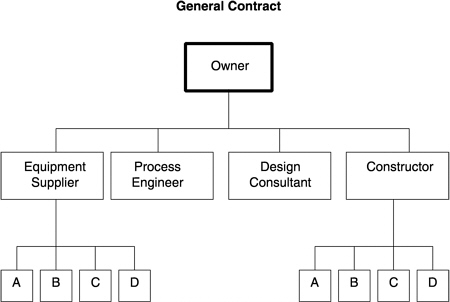

The extent of owner engineering downsizing and the resulting increased use of contractors to perform design and construction functions are illustrated by Figure 2.2 and figure 2.3. The graphs, published by The Business Roundtable, are based on data compiled by Independent Project Analysis (IPA) of Reston, Virginia, for more than 2,000 projects from a variety of industries.

Figure 2.2 shows the decline since 1970 of the percentage of major projects designed by owners' in-house staff. The rate of decline has accelerated since 1985. Many owners originally identified the project definition activity as a core competency (defined as an essential skill that should be retained within the organization in order

FIGURE 2.2 Owner-detailed engineering has almost disappeared. Source: TBR (1997).

FIGURE 2.3 Engineering contractors are more involved in definition. Source: TBR (1997).

to perform effectively). However, IPA's data indicate that project definition, too, is increasingly being outsourced (Figure 2.3). Data compiled through 1997 by the Construction Industry Institute (CII)1, closely correlates with The Business Roundtable data (CII, 1998). Fortunately, an increasingly competitive, productive, sophisticated, and capable facility design and construction industry is capable and willing to take on this increased workload. Unfortunately, this trend has not reduced owners' overall engineering costs as a percent of total project cost (TPC).2

Figure 2.4 shows that the engineering share of TPC has increased over the past 20 years from 13 to 20 percent. The interpretation of this increase is controversial: It is not clear if the increase reflects an increased cost of outsourced engineering or simply the cost of increased intensity of engineering required by today's technology-driven projects and more sophisticated design and construction practices.

TRENDS IN PROJECT COST AND SCHEDULE

Ongoing research by CII into construction industry benchmarking and metrics indicates that overall project cost and schedule, as well as postcontract award cost and schedule growth, are being reduced throughout the construction industry. Nearly everyone is enjoying some degree of increasing productivity, a classic case of “a rising tide lifts all ships.”

CII's research divides facility owners and construction contractors into four quartiles in terms of cost and schedule growth experienced on completed projects. In comparing results from approximately 1,000 projects of various types, CII found that owners and contractors in the first quartile (top 25 percent) are currently completing their projects with 30 percent cost saving (as measured from the original project budget estimate) whereas owners and contractors in the fourth quartile (bottom 25 percent) are seeing 10 percent cost growth. CII attributes differences in performance between owners and contractors scoring in the first quartile and those scoring in the fourth quartile primarily to the intensity with which they utilize new and innovative project management approaches.

|

1 |

CII's membership includes several federal agencies, including the General Services Administration, Army Corps of Engineers, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, NASA, U.S. Department of State, Tennessee Valley Authority, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology. |

|

2 |

TPC is defined as the sum total of all costs associated with a project 's planning, development, design, construction, outfitting, and start-up, not including land costs. |

FIGURE 2.4 Overall engineering costs have continued to climb. Source: TBR (1997).

The finding that the gap between contractors and owners in the first and fourth quartiles is increasing over time is also noteworthy. This suggests that owners and contractors that are open to change and innovation of their business practices (and who are able to successfully implement such change) enjoy a competitive advantage that can be further increased (CII, 1998). The Business Roundtable report further corroborates this finding (TBR, 1997).

CONTRACTING METHODS

Since 1993, federal regulations have been modified to allow agencies greater flexibility and choice in the contract method used for acquiring facilities. Downsizing and the increased outsourcing of design and construction services have provided the impetus for selecting methods other than the traditional design-bid-build contract method.

Although there are many variations, current practice recognizes four basic categories of contract types that apply to several facility acquisition systems:

-

general contract,

-

construction management,

-

design-build, and

-

program management.

The following discussion is based on data developed by the Associated General Contractors of America and General Motors Corporation. The figures represent generalized concepts of the owner's relationship to the various service providers and may vary in implementation, depending on the project.

The general contract approach, as illustrated in Figure 2.5, assumes that the owner contracts individually for all engineering and construction services required to acquire a facility. This is the traditional approach that most large-scale owners (both public and private) used to design and construct their facilities until the relatively recent growth of interest in outsourcing of design and construction services. It is illustrative of the design-bid-build contract method used by federal agencies.

Under the general contract approach, the owner manages individual contracts with all design, engineering,

FIGURE 2.5 Generalized concept for general contract approach. Source: AGC (1993).

and construction service providers, implying that the owner must also manage all interfaces between service providers. Under this approach it is common for owners to enlist outside consultants for various functions of the acquisition process. Interface management becomes critical because assessment of accountability for problems incurred during the project's evolution is difficult due to the variety and separation of individual contracts. To succeed, such a process requires a relatively large and experienced facility design, engineering, and management staff within the owner's organization in order to protect the owner's interests.

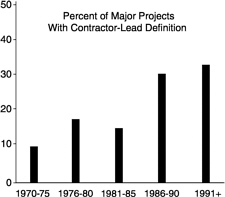

Construction Management

A first step toward outsourcing construction management services during facility acquisition is reflected in the construction management approach, illustrated in Figure 2.6, wherein the owner contracts with an outside firm to manage the construction of a project. Under the construction management approach, the construction manager (CM) may function either as an “agency” CM, or as an “at-risk” CM:

-

Agency CM: The owner holds all individual construction contracts, and the CM functions as the construction contract administrator, acting on behalf of the owner and rendering an account of activities. Actual construction work is performed by others under direct contract to the owner, and the CM is typically not responsible for construction means and methods, nor does the CM guarantee construction cost, time, or quality.

-

At-risk CM: The actual construction work is performed by trade contractors under contract to the CM, who then becomes responsible to the owner for construction means and methods and delivery of the completed facility within the owner's scope of work for cost, time, and quality.

Under the construction management approach, the owner typically retains responsibility for managing all preconstruction A/E services, and therefore must address all interface issues between service providers.

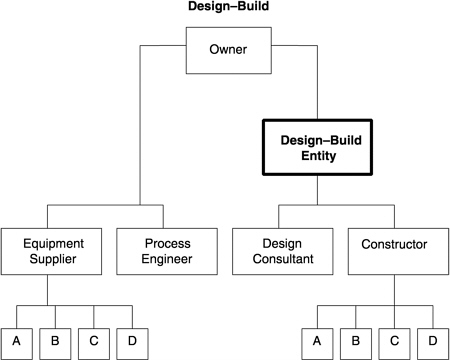

Design-Build

The design-build contract method, as reflected in Figure 2.7, represents a much larger step toward outsourcing of traditional owner functions than occurs with the above-described construction management contract. Under the design-build approach, an owner prepares a project scope definition and then engages a single entity that will provide all services necessary to complete the design and construct the facility. Generally, the scope definition package represents a design that is between 15 and 35 percent complete, although variations of the design-build approach may begin much earlier, often with a performance specification, or much later with perhaps a 65 percent design package.

Project success under the design-build approach is primarily dependent on the owner's ability to produce a comprehensive, well-defined, and unambiguous scope of work upon which all subsequent design-build activity will be based. Once the design-build contract has been awarded, changes to owner requirements will generally incur heavy penalties to the project cost and schedule. The owner is therefore well advised to ensure that preparation of the project scope definition package accurately and clearly expresses expectations for project performance, quality, cost, and schedule.

FIGURE 2.7 Generalized concept for design—build contracts. Source: AGC (1993).

Use of the design-build approach for project delivery is growing dramatically in both public and private organizations; the Naval Facilities Engineering Command, the General Services Administration, and the U.S. Postal Service have become particularly strong proponents of this approach, but not without controversy. The Design Build Institute of America recognizes that management processes and owner and contractor relationships must change significantly from the more traditional approaches for design-build to be successful. The Institute therefore recommends that both owners and contractors electing to use this approach thoroughly train those who will either manage or participate in such a process.

Program Management

The program management contract method, as reflected in Figure 2.8, represents the ultimate step in outsourcing of the owner's project management functions. The program manager (PM) is engaged by the owner to exercise oversight of the entire facility delivery process for a multitude of projects, from planning through design, construction, outfitting, start-up, and postoccupancy activities. Similar to the construction management approach, the PM can serve in either an “agency PM” or “at-risk PM” capacity:

-

Agency PM: The owner holds all individual contracts, and the PM functions as the contracts administrator, acting on behalf of the owner and rendering an account of activities. All project work is performed by others under direct contract to the owner, and the PM is typically not responsible for project means and methods, nor does the PM guarantee cost, time, or quality.

FIGURE 2.8 Generalized concept for program management contracts. Source: AGC (1993).

-

At-risk PM: All project work is performed by service and trade contractors under contract to the PM, who then becomes responsible to the owner for project means and methods as well as delivery of the completed facility within the owner's objectives of cost, time, and quality.

With the PM responsible for managing the interfaces between all phases of facility acquisition and all parties involved, the owner's personal participation in the facility acquisition process is minimal. Taken to the extreme, some private sector organizations have completely eliminated their in-house facility engineering capability by entering into a long-term (or even permanent) contractual relationship with an outsourced PM. The industry is watching this relatively new approach carefully, and the results to date are inconclusive.

There are many variations to the four basic contract methods. Indeed, each day seems to bring yet another new and innovative adaptation. Nonetheless, the trend is unmistakable: Evolving contract mechanisms and owner and contractor interfaces require a much closer and collaborative relationship between parties than has traditionally been the case with the facility acquisition process.

TEAMWORK AND COLLABORATIVE PROCESSES

The facility acquisition process traditionally has been an adversarial environment, with facility owners, designers, and constructors separated by formal contractual documents and backed up by teams of lawyers. Time and again, conflicting interests between the parties resulted in poor communication, poor problem solving, and poor results. In the early 1980s, several organizations, among them the Army Corps of Engineers and the Arizona State Highway Department, attempted to instill a new philosophy wherein the interested parties to a facility acquisition would collaborate on areas of common interest rather than defend areas of proprietary conflict. These early proponents devised a highly structured process intended to enhance communication, engender trust between the parties, and align all parties toward the common objective of achieving a quality facility. The process is commonly referred to as teambuilding. The techniques underlying teambuilding are applicable to almost any endeavor requiring the cooperation of individuals to achieve a common goal; the team may be wholly internal to an organization, or it may involve participants from unrelated organizations.

When multiple organizations make a commitment to work cooperatively toward a common objective utilizing teambuilding techniques, the practice is called partnering. Partnering may be a relatively short-term relationship in the case of completing a single project, or it may become a longer-term relationship with the committed organizations cooperating for a multitude of projects. Some private sector facility owners have even elected to form permanent and enduring commitments with selected A/E firms and construction contractors with the intent that these firms will be the sole providers of engineering services for the foreseeable future. Such relationships have been commonly referred to as strategic alliances.

The facility acquisition process is inherently a group activity, with participants from a wide variety of perspectives, both internal and external to the owner's organization. Teambuilding and partnering practices are therefore uniquely appropriate for enhancing effectiveness of the facility acquisition process. Teambuilding in general and partnering in particular are not easy to implement. It is not within the scope of this study to provide a treatise on teambuilding and partnering. However, several sources of information on teambuilding and partnering are included in Appendices B and appendix E.

When approached effectively, teambuilding and partnering results can be truly impressive, as noted in NASA's recently published Partnering Desk Reference Guide:

The Arizona Department of Transportation, formerly averaging $5 million annually in litigation costs, did not have a litigated claim on any of the over 400 projects partnered from 1991 to 1997. The Texas Department of Transportation and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers have both experienced decreases in litigation almost as dramatic. For those organizations that have “Mature” partnering programs, litigation is no longer an issue (NASA, 1999).

OWNER AS A “SMART BUYER”

As noted above, American business has regained its competitive edge by reengineering its business practices to improve their effectiveness and in the process, downsize their in-house staff. However, competitive pressures caused many organizations to approach staff downsizing without adequate planning. Mistakes were made: Reductions were insufficient, or too extensive, or made in the wrong area.

Some government agencies found themselves with an even more difficult staffing challenge where reductions were mandated by arbitrary staff reduction quotas not necessarily linked to process reengineering. The Business Roundtable, in their 1997 white paper The Business Stake in Effective Project Systems noted:

Of particular concern, [retention of] the technical competence to assist the businesses in arriving at the most appropriate project to meet the business need has been lost along with the competence to execute the project effectively (TBR, 1997).

The loss of technical competence through downsizing was sufficiently pervasive that the Federal Facilities Council (FFC), in conjunction with The Business Roundtable and the Naval Facilities Engineering Command, conducted the “Government/Industry Forum on Capital Facilities and Core Competencies” in March 1998. A fundamental finding of this forum was that owner facilities engineering organizations need to identify and retain core competencies—the essential technical and managerial skills that cannot be outsourced without serious risk to an organization's ability to conceive and acquire necessary facilities. The forum participants recognized the advisability of the owner performing as a “smart buyer” of outsourced services. A smart buyer is one who retains an in-house staff capable of

-

understanding the organization's business or mission, its requirements, its customer needs, and who can translate those needs and requirements into corporate direction or mission;

-

accurately defining the technical services to be contracted;

-

evaluating the quality, performance effectiveness, and value of technical work performed by contractors; and

-

managing the interface between technical service contractors and the owner's line-of-business managers who will ultimately benefit from services provided (FFC, 1998).

These functions are intrinsic to the entire facility acquisition process and underscore the need for the owner's in-house staff to be intimately involved in these aspects of the process, particularly the leadership role.

CONCEPTUAL OR ADVANCE PLANNING

Research by the National Research Council (NRC), the CII, The Business Roundtable, and others point to the importance of conceptual or advance planning to the entire facility acquisition process. Predesign phases of the decision-making process are critical because it is during these phases that the size, function, general character, location, and budget for a facility are established. Errors made at this stage are usually embodied in the completed facility in such forms as inappropriate space allocations or inadequate equipment capacity (NRC, 1989.)

A 1990 NRC report found that for federal facilities, one of the key factors in design-related growth of construction costs in excess of budget is poor planning and failure to think carefully about foreseeable problems of construction. This report also found that the early stages of the design process are most critical for assuring successful design to budget because the design is still flexible and factors that determine cost are not fixed (NRC, 1990).

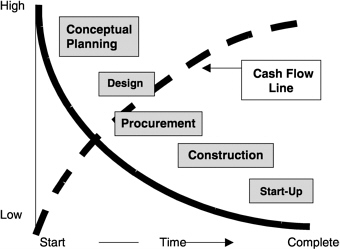

Much of the current work to improve design and construction industry business practices is based on the concept illustrated in Figure 2.9.

The cost influence curve (the solid curve in Figure 2.9) indicates that the ability to influence the ultimate cost of a project is greatest at the beginning, during the conceptual planning phase, and decreases rapidly as the project matures. Conversely, a project cash-flow curve (the dashed curve in Figure 2.9) indicates that conceptual planning

FIGURE 2.9 Cost Influence Curve. Source: CII (1986b).

and design costs are relatively minor and that costs escalate significantly as the project evolves through the procurement, construction, and start-up phases. The implication is obvious: Conceptual planning and design should be as comprehensive and thorough as possible and not driven primarily by cost considerations.

These concepts underscore the critical importance of having intensive owner involvement in the development of the scope of work and conceptual planning processes. The Business Roundtable, in fact, has stated that

The supply chain of a capital project starts with the identification of a customer need that might be translatable into a business opportunity. The front-end loading process is made up of the critical planning phases of the project. It is called front-end loading because the effective commitment of time and resources at this point dictate the future success of the project. . . . It is because of the central role of front-end loading that project excellence cannot be bought in the market like a commodity (TBR, 1997).

COST IMPLICATIONS OF FACILITY ACQUISITION PRACTICES

It should be intuitive that poor project planning and design practices result in increased total project cost (TPC). These cost growth drivers include

-

construction change orders required to correct errors and omissions in the design documents;

-

owner-driven construction change orders required to incorporate desirable features overlooked during design;

-

inefficient construction resulting from a failure to incorporate construction-enhancing features during design;

-

rework resulting from unclear construction documents;

-

standby costs incurred while construction is either stopped or slowed to incorporate changes;

-

litigation;

-

delayed completion of the facility (i.e., lost business revenue, staff standby, nonproductive capital investment costs); and

-

a poorly performing facility.

Numerous research reports have been published characterizing cost growth resulting from poor planning and design practices. The following are a few of the key statistics contained in documents abstracted for this study:

-

Project design costs average 13 percent of TPC (CII, 1998).

-

Total project engineering costs average 20 percent of TPC (in addition to design costs discussed above, includes planning, development, and project management costs) (TBR, 1997).

-

Project rework costs average 12.4 percent of TPC. Eighty percent of this rework results from errors and omissions in the design documents. The remaining 20 percent results from poor construction practices (CII, 1989a).

-

Fifty percent of construction change orders result from errors in the design documents directly related to improper interfaces between design disciplines (civil, structural, architectural, electrical, and mechanical). These change order costs contribute anywhere from 0.8 to 3.4 percent of TPC (Nigro and Nigro, 1992).

-

Comprehensive review of project document development during the design phase of acquisition should cost from 0.2 to 0.5 percent of TPC. Properly done (i.e., using best practices discussed later in this study), such activity should drive down the cost of construction change orders by an average of 3 percent of TPC (CII, 1993).

-

To evaluate the value of thorough concept definition, a 1993 CII-led review of 62 projects compared final TPC against the estimated TPC at time of project approval for construction. The 21 projects with the highest degree of definition averaged 4 percent cost underrun. The middle 21 projects averaged 2 percent cost underrun. The 21 projects with the lowest definition averaged 16 percent cost overrun (CII, 1994).

-

Indirect costs, the business impact costs discussed above, are highly variable and very difficult to estimate, but are potentially huge. An order-of-magnitude estimate would be 8-15 percent of TPC (CII, 1989b).

The implication of these statistics is that opportunity exists to significantly reduce TPC by conducting an effective design review process. The potential savings range from a minimum of 3 percent to as much as 20 percent, and even higher when indirect savings are taken into account.

Research conducted by Redichek Associates, an A/E firm specializing in outsourced design review, indicates that the single biggest source of construction change orders (approximately 50 percent) is errors in the design documents directly related to improper interfaces between design disciplines (civil, structural, architectural, electrical, and mechanical). Redichek's cost for conducting the discipline interface design review is approximately 0.1 percent of TPC, with a resultant reduction of rework cost ranging from 0.8 to 3.4 percent of TPC. The estimated payback ratio here ranges from $8 to $34 saved for every dollar invested in a discipline interface design review activity.

Intuitively, good design review practices result in the preparation of more comprehensive and accurate construction documents, which in turn result in lower project construction costs. Areas of savings include less rework on the part of the construction contractor, fewer change orders to the owner for correction of design errors or omissions, and the cost of belatedly adding project upgrade features that should have been addressed in the original design. By reducing changes that are required during the construction phase, good design review practices also generate significant indirect cost savings by avoiding costs associated with loss of productivity during construction-delayed facility start-up, and litigation.

BENCHMARKING AND METRICS

One of management guru Edward Demming's fundamental principles is “If you can't measure it, you can't manage it.” His method of improving performance of any process first requires identification and documentation of a series of objective criteria (“metrics”) that characterize the level of process efficiency. Armed with such data,

the researcher can next compare his or her process efficiency with a similar process as performed by another organization to determine whose process is the most efficient. This process of comparison is called benchmarking. The real value of benchmarking results from follow-up activities:

-

Identifying the similarities and differences in competing process practices.

-

Understanding which practices in the best process produce such good results.

-

Incorporating the best practices into one's own process, measuring the results achieved, and documenting the extent of improvement.

Several organizations have conducted benchmarking activities within the construction industry, including IPA of Reston, Virginia. IPA 's database encompasses metrics from over 2,000 individual projects valued at over $300 billion and accomplished by approximately 60 companies. Although the IPA database is proprietary, IPA has collaborated with research studies such as The Business Roundtable white paper The Business Stake in Effective Project Systems. IPA also helped the CII implement a benchmarking activity within its membership. Several of the FFC sponsor agencies are also members of the CII and are participating in ongoing CII benchmarking. The CII benchmarking program uses the following definitions and objectives:

Benchmarking: A systematic process of measuring one's performance against results from recognized leaders for the purpose of determining best practices that lead to superior performance when adopted and utilized.

Metrics: A quantifiable, simple, and understandable measure, which can be used to compare and improve performance.

The principles of benchmarking are appropriate for those organizations interested in measuring and improving the relative performance of their facility acquisition and design review processes.

TECHNOLOGY AND DESIGN REVIEW

Some philosophers hold that the impact of information science on society is so great that it constitutes a fourth “age”—the information age—ranking with the agricultural age, the iron age, and the industrial age in importance. The information age is all about calculating, validating, documenting, and communicating information. It has already caused a profound transformation of the facility acquisition process, with that transformation continuing to accelerate. Slide rules have given way to calculators and computers. Drafting tables, T-squares, and triangles have been replaced with computer-based automated design and engineering. Construction documents are now stored, published, and distributed electronically rather than through massive paper trails. Today it is common to use computers to construct and display three-dimensional models of projects in order to check for interference fits and visualize architectural and structural features. The newest four-dimensional models are even able to visually “construct” the project over time to identify constructability issues.

Today it is literally possible to conduct design review activities as the design evolves, almost as if standing over the shoulder of the design A/E. Audio conferencing, video conferencing, and Internet connectivity allow design reviews to occur in real time as virtual meetings without the need to assemble teams and documents at designated locations. Indeed, the problem becomes one of information overload —with so much data so easily available, reviewers must become proficient at managing this data flow in order to exploit the opportunity it presents.

This marriage of architecture, engineering, and computer sciences is relatively new, but widely recognized. For example, the American Society of Civil Engineers now publishes a periodical dedicated to this area, The Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering. Stanford University has established the Center for Integrated Facility

Engineering encompassing the colleges of Civil Engineering, Architecture, and Computer Sciences. The CII has made Information Technology and Electronic Data Management one of its core research topics. To be successful, today's facility acquisition managers must look beyond mastering the technical details inherent to project performance, quality, cost, and schedule. They must also become information managers, conversant and comfortable with the newest tools by which information is documented and distributed.

EFFECTIVE DESIGN REVIEW PROCESSES: CONCLUSIONS

As the foregoing discussion indicates, during the 1980s and 1990s, a number of business practice studies were conducted by construction trade associations, professional societies, and academic groups to better understand which practices produced better results in terms of facility performance, quality, cost, and schedule. These studies concluded that quality design yields buildings that perform well throughout their service lives (NRC, 1989). Quality design resulted when all interested parties (owner, user, A/E, construction contractor, and specialty consultants) in the facility acquisition process worked together in an intense, collaborative, complex, and multiphased process beginning with conceptual planning and concluding after the start-up phase.

These business practice studies also found that decisions made during the conceptual planning phase will establish initial constraints limiting future design flexibility. These early decisions thus have a disproportionately greater influence on a facility's ultimate performance, quality, cost, and schedule than decisions made later in the process. The conceptual planning phase should therefore be the phase when the review of designs is most intense, with the primary focus upon ensuring the appropriateness, accuracy, and thoroughness of the owner 's expectations regarding facility performance, quality, cost, and schedule. This will be especially true when using the design-build and program management contract methods when the owner's involvement in design reviews declines after the conceptual planning phase.

If design review activity during the conceptual planning phase has resulted in a clear scope of work regarding the owner's expectations, design reviews during the design phase are greatly simplified. Those parties involved should focus upon ensuring that the evolving facility design incorporates high standards of professional engineering practice with regard to architectural, civil, structural, electrical, and mechanical systems and their interfaces. Formal reviews may be scheduled periodically during the design phase, at approximately the 35, 60, 90, and/or 100 percent design completion milestones (although these milestones may vary significantly depending on the individual project 's size and complexity). Such structured formality helps ensure the widest possible participation of interested parties during the review, including specialists and consultants who bring expertise in such areas as value engineering, constructability3, biddability4, operability, maintainability, and environmental compliance.

During the procurement phase, the review of designs can continue to contribute to overall project success by monitoring progress made in ordering the various items of long-lead-time equipment. It is not unusual for suppliers to detect errors in the ordering specifications, or to make substitution recommendations for either greater economy or performance enhancement. The review team should evaluate the impact of these changes on facility performance, quality, cost, and schedule.

It is almost inevitable during the construction phase that scope of work changes by the owner, errors and omissions in the plans, unknown or changed site conditions, and creative initiatives on the part of construction staff will result in recommended changes to the facility design. Design reviews in this phase should focus on assessing the impact and advisability of changes on facility performance, quality, cost, and schedule.

Design reviews should continue into the start-up phase. At this juncture it is important to document the results achieved by conducting what is commonly referred to as a postoccupancy evaluation, whose purpose is to record

|

3 |

In constructability reviews, experienced construction managers look for such items as inappropriate materials, physical barriers, and complex interfaces that will unnecessarily complicate the construction phase. |

|

4 |

In biddability reviews, procurement specialists look for conflicts, errors, omissions, and lack of clarity in the construction documents that could create confusion on the part of prospective equipment suppliers or construction contractors. |

lessons learned for future reference. Facility performance, quality, cost, and schedule actually achieved should be objectively measured and compared with the owner's original expectations. Lessons learned during the five facility acquisition phases concerning design strengths and weaknesses should be recorded for use in improving future similar project activities. And perhaps most important, the facility users ' subjective satisfaction with both the acquisition process as well as the completed facility should be noted.

Based on industry research by the CII, the NRC, the FFC, and similar organizations, interviews conducted for this study and the author 's experience, it can be concluded that an effective design review process will be structured to address all of the following topics:

-

Owner satisfaction: Does the constructed facility meet the owner's expectations as originally defined by the project scope definition or statement of work (i.e., performance characteristics, architectural statement, level of quality, cost, schedule, and any relevant owner-published standards and/or policies)?

-

Sound professional practice: Is the approach taken in each of the specialty areas (architectural, civil, mechanical, and electrical) commensurate with professional standards?

-

Code compliance: Does the design comply with all applicable codes such as fire protection, life safety, and access?

-

Architectural statement: Is the overall presentation representative of established architectural standards?

-

Value engineering: Are there any less expensive methods or materials that could be used in the design without impacting project quality or performance?

-

Biddability: Are the construction documents sufficiently clear and comprehensive so construction contractors will have no difficulty developing an accurate bid with minimal allowance for contingency?

-

Constructability: Does the design impose any unnecessarily difficult or impossible demands on the construction contractor?

-

Operability: Does design of the facility operating systems ensure ease and efficiency of operation during the facility's useful lifetime?

-

Maintainability: Does the facility design allow for easy and cost-effective maintenance and repair over the useful life of the facility?

-

Life-cycle engineering: Does the design represent the most effective balance of cost to construct, cost to start up, cost to operate and maintain, and (perhaps most important) the user's cost to perform the intended function for which the facility is being acquired over the useful life of the facility?

-

Postoccupancy evaluation: Based on a review of the construction, start-up, and ongoing functioning of the facility, could any unexpected difficulty have been avoided by a different design approach?