1.4 DESIGNING A COMMON COMMAND AND INFORMATION INFRASTRUCTURE

1.4.1 The Naval Command and Information Infrastructure Concept

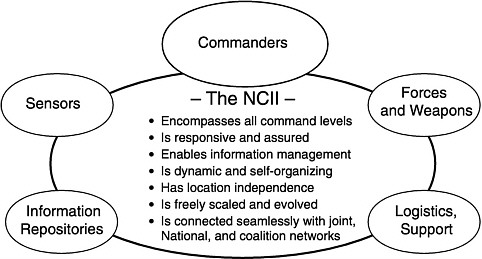

The Naval Command and Information Infrastructure will become the enabling framework for network-centric operations. The NCII includes the communications trunk lines, terminals, tactical networks, central processing facilities, common support applications, and Department of Defense (DOD)-wide and commercial standards, rules, and procedures that will enable the flow of raw and processed information and commands among units at all levels of command. Its attributes are listed in Figure 1.6, an expansion of Figure 1.1.

All the Services are striving to achieve the capability to share information, based in large measure on the Internet paradigm. The Internet's robust, networked communications base enables rapid, ready, and flexible access to information and supports the applications that provide information and services to a widely dispersed user population. Some top-down principles and standards are necessary for the communications base so that the applications can easily use it and so that users can interoperate with applications. In the Internet applications are developed from the bottom up by a diverse developer population. Thus there is a broad base for innovation, an important factor contributing to the utility of the Internet. The point for the NCII is that it should use standards that will permit its applications to come from diverse sources to serve a diverse set of users. In this respect, the Internet is the best model available to describe the design approach for the NCII.

FIGURE 1.6 Attributes of the Naval Command and Information Infrastructure.

As with the Internet, users of the NCII will not be satisfied with, nor will their needs be met by, some fixed, predefined set of information. The uncertainty as to the type and location of future military operations ensures that. Relatedly, different operators may vary in their approach to a situation, and hence in their information needs. Furthermore, the manner in which information is used in the NCII will change continually as operational concepts are refined and new technologies introduced. For all these reasons, a central notion of the NCII is that it be flexible, adaptable, and evolvable in meeting the needs of its users.

While the NCII includes tactical networks and allows for widespread dissemination of information, it must also accommodate the need of commanders for some degree of control over such dissemination, for, among other things, security purposes and bandwidth management. This management of information dissemination facilitates and allows for decentralization of command, but at the same time it allows for the centralized collection of information and hence for greater centralization of authority. There is no one generally appropriate point to aim for on this centralization-decentralization spectrum; it will depend on the nature of the military operation. The NCII must be able to support varying modes of command.

The NCII is conceived not only as carrying long-haul traffic but also as enabling short-haul and tactical information acquisition, processing, and transfer. The acquisition of raw information and its processing into an accurate understanding of the current details of environments, forces, targets, and maneuvers must be treated separately from the transport (communication) of the information and the commands based on it. The NCII provides for the integration of the acquisition and processing mechanisms and provides the transport for information and command at all levels, from major force operations to single target-shooter engagements.

The mechanisms for transporting information for many services and functions will rely heavily on civilian, commercial systems. Purely military functions will appear more in the information processing and command parts of the NCII, where security and the special characteristics of military operations are driving factors, although purely military functional capabilities will be built in good measure from commercial sources and technology.

The NCII should be recognized as the naval force portion of an information infrastructure that is interwoven with, shares common components with, and adheres to the same set of standards as other Service, National, and, when appropriate coalition networks, such that all function as a global whole. Thus, the NCII will have to be built to standards established by others, although the Department of the Navy should play a part in developing some of the standards. Since the network will have commercial components, the standards will also have to be compatible with and often the same as commercial standards. These standards, and the rules and coordinated operational procedures that go with them, will be the only means by which full interoperability can be achieved. Full inter-

operability will be essential to bring all the benefits and advantages of network-centric operations to fruition.

Tactical networks are of special concern since they pose the greatest challenge to the goal of using standard, Internet-based networking technology throughout the naval infrastructure. The Navy and the Assistant Secretary of Defense for C3I (ASD (C3I)) have argued that this class of radio networks must necessarily be based on nonstandard, military-developed technology to meet the tight time constraints and extreme reliability that tactical communications require. Accordingly, the current Navy networking architecture defines two special-purpose tactical radio networks in addition to the standards-based Joint Planning Network: the Joint Data Network (actually, the Joint Tactical Information Distribution System (JTIDS)) and the Joint Composite Tracking Network (atually, CEC).7 Although the Navy and ASD (C3I) argument has merit, the committee concluded that there are greater advantages in extending a uniform, open, standards-based network architecture across the entire naval infrastructure, including the tactical networks. The committee envisions a network in which tactical data communications are provided via the NCII standards, including a standardized naming and addressing scheme and data transport using the Internet Protocol (IP). The committee believes that advancing commercial technology will make it possible to remove technical impediments to allowing any type of data to be conveyed across any type of radio link.8 If an Internet-based architecture is adopted, new types of tactical services can be rapidly deployed across inplace radios.

It is important to note that the committee does not believe that all types of traffic should be allowed to cross any tactical radio network freely. Quite the contrary: Strict controls will be necessary at the connection points between the tactical and nontactical portions of the NCII. These controls will ensure that only authorized types of traffic are allowed onto the tactical networks, and hence they will provide continued guarantees that the tactical networks can provide highly reliable, low-latency data services. These controls will also aid in providing security boundaries (i.e., firewalls) within the NCII as part of the network defense in depth discussed in Section 1.4.2.

In the end, it is likely that a few tactical networks will remain outside the NCII for some combination of technical and economic reasons. Such outlying tactical networks can be connected into the Internet-based NCII via IP-capable

|

7 |

Furthermore, as far as the committee can tell, this focus on the Joint Data and Joint Composite Tracking Networks omits consideration of all other tactical communications networks currently employed by the Navy that are part of the overall information transfer capability. These include various sensor links—e.g., for MTI and synthetic aperture radar data—and links to weapons control systems—e.g., ultrahigh frequency satellite communications target location updates for Tomahawk. |

|

8 |

Approaches to this are described in some detail in Appendix E. |

gateways so that they can still enjoy the advantages of being part of the overall, seamless naval network infrastructure.

It is important to understand that the NCII itself does not represent a major new investment. Rather, it requires an investment of resources sufficient to integrate the many subsystems and components, some of which exist, some of which are being developed, and some of which are or may be planned, in a way that provides guidance and structure for an overarching concept for information support to network-centric operations.

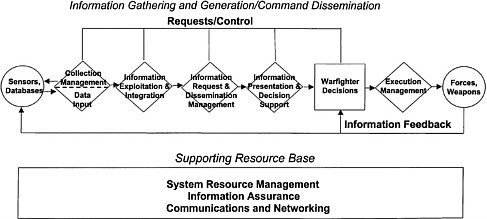

The general composition of the NCII is illustrated by its functional architecture, shown in Figure 1.7 and discussed in detail in Chapter 4. The starting premise of this functional architecture is the need to support the warfighting decision process extending across all levels of command, to include those engaged in actual weapons delivery. Shown in the top half of the figure are the functional capabilities (collection management, etc.) that gather and generate information to support the decision process, and then see that the decisions are conveyed to their appropriate recipients. Across the bottom of the figure are the supporting resources (communications, etc.) used by the “upper level” functional capabilities.

Collection management determines the tasking of sensors to collect data. The information exploitation and integration function takes the initial data and refines the information by correlating, fusing, and aggregating it. Information request and dissemination management provides information based on user-specified requests for a given type of information. Its operation is transparent in that users do not have to know the details of where the information is located. This function will also provide information to users based on the directions of any other authorized party. Information presentation and decision support includes the graphical means for displaying information to users and the set of automated

FIGURE 1.7 Functional architecture of the Naval Command and Information Infrastructure.

tools that allows users to manipulate information for the purposes of making a decision. Execution management supports delivery of decisions to the intended recipients and allows for dynamic adaptation of those decisions in the light of rapidly changing events. The other functions illustrated in Figure 1.7 are self-evident.

1.4.2 Information Assurance Within the NCII

“Information assurance” is the term used in this report to describe how threats to and vulnerabilities of the NCII must be addressed to ensure the integrity of information and the timeliness and continuity of its flow for network-centric operations as a whole.

The NCII, like all information networks in the modern age, must routinely exhibit high reliability and must include safeguards against system failures due to overload, loss of critical nodes as a result of enemy action, and other operational factors. It will also face many threats to the quantity, quality, integrity, and continuous flow of the information it manages and provides, and it will have many vulnerabilities. Both the threats and the vulnerabilities are too numerous to elucidate in this summary discussion. They are noted briefly here and are described in detail, along with potential defenses and countermeasures, in Chapter 5.

Critical vulnerabilities for tactical networks are spoofing, jamming and other interruptions, interception, and ground terminal capture. Important sources of weakness in the NCII transport elements will derive from the use of commercial subsystems and from the outsourcing of important elements of the transport operations, and also from the need to connect with and share information with coalition partners. The key strength of the NCII in allowing the connection of disparate networks and functions is also, however, a source of risk. Among these connections is that linking the fleets' operational networks, in which a degree of secrecy and control can be maintained, with the naval force business networks that are essential for the logistic support of the fleet and that must be open to both the naval forces at sea and their shoreside commercial connections. A critical vulnerability in the nontransport part of the NCII derives from the threat posed by the potential malicious insider, who could, working alone or with outside adversaries, cause serious disruption to network-centric operations.

NCII information assurance must be achieved throughout the information infrastructure, including wireless links. In the design of the NCII, all components must be treated as vulnerable, and security vulnerabilities must be anticipated in any system component and even in any given protection mechanism. Overall, to meet the threats and mitigate the vulnerabilities, a defense in depth is required. It consists of three elements: prevention; detection of attack, assessment of the damage, and remedying of the effects of the attack; and robustness in its ability to tolerate penetrations.

Today, because of technology shortfalls at each level of the defense-in-depth strategy, it is not possible to completely implement such a strategy. However, in some cases steps that do not depend on technological remedies can be effective. For example, in a crisis certain functions may be considered so critical that any risk to their timely and correct functioning is intolerable. In such cases, the decision may be to not connect, and to use an air-gap defense (which inserts a deliberate break, to be connected by manual action, in a link of the network). Reducing the risk of damage by a malicious insider might be accomplished by reducing the scope of access and control available to any single individual, and by requiring two- (or more) person control of key functions. Monitoring user activities, coupled with exploring observed anomalies, is another risk-reduction technique.

Red teaming is often prescribed for exposing a system's vulnerabilities and weaknesses so that they can be remedied. However, it is important to understand and capitalize on red teaming's strengths while understanding the limitations of its use. Red teaming proves not to be a preferred way of discovering system vulnerabilities or learning how to mitigate threats, because the red teams come from the same culture that created the system. Red teaming's primary benefits are that it is the best tool for raising the level of security awareness within an organization and that it is useful as a method for ensuring that correct security configurations are maintained for the system. Red teaming for these purposes can be carried out by a system's security staff on a periodic basis.

In its review, the committee found that information assurance for the NCII is not receiving appropriate attention at high enough levels within the Department of the Navy to ensure that this critical problem area is managed in a manner consistent with its importance to successful network-centric operations. There is no single individual in the Department of the Navy charged with the responsibility for information assurance. Further, the Navy Department has no overall plan for information network security in its tactical networks. Mitigation of vulnerabilities will come from many measures in the defense in depth, with support from continual red teaming, but the organizational problems will have to be remedied as well.

In addition, because of the likelihood of attack on the NCII or its operational degradation, it is imperative that naval forces train for situations with impaired NCII function. Not only must the NCII system staff learn to quickly restore service, but the operational forces must also learn to deal with system failures. Beyond that, in recognition of the vulnerabilities the forces should be shaped such that they can fall back to operational modes that are at least as good as those that preceded network-centric operations. For example, the naval forces have a tradition of developing operational workarounds for loss or degradation of radio frequency communications in tactical operations. The same should be done for the NCII so that naval forces will be prepared to deal with these likely situations in practice.

In the spiral development process, especially in the experiments and proof-of-concept exercises that will attend the development of concepts of operation, the opportunity will exist to probe for the most logical vulnerabilities (e.g., jamming of tactical networks) and to design appropriate redundancies and fallback modes of operation.

Is it worth accepting all the vulnerabilities and the attending risks, as well as the cost and operational penalties of anticipating and remedying them? This is a question that cannot currently be quantified. However, in all recent military endeavors, including the Gulf War and operations in the Balkans, and in endeavors throughout the national and even the global economy, the gains are seen as being so great that the risks are accepted even while mitigation attempts are undertaken and their costs incurred. The trends in technology, force size and utilization, and U.S. global responsibilities are such that network-centric operations offer the only means of achieving the necessary mission effectiveness of U.S. naval forces.

1.4.3 NCII Functional Capabilities: What Exists and What Is Needed

Table 1.1 and Table 1.2 summarize the status of the currently programmed baseline elements of the NCII and the challenges that must be met to give it the capabilities needed for network-centric operations to function as envisioned.

There are many naval, defense agency, and commercial endeavors that can contribute to the development of the NCII. These include the Navy's IT-21 strategy; the Navy/Marine intranet; the Global Command and Control System– Maritime; software radios that can emulate multiple legacy radios and also adaptively select appropriately robust waveforms; the design guidance in the Information Technology Standards Guidance; naval communications and software research at the Office of Naval Research, Naval Research Laboratory, and Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command (SPAWAR); and—in a broader sense—the DOD Global Information Grid as it becomes more specifically defined. In addition, there are valuable DARPA programs that can help advance NCII capabilities in the areas of challenge listed in Table 1.2, including work on information assurance and survivability, dynamic system resource management, agent technology, and data visualization, among others. However, these ongoing developments do not constitute a comprehensive approach to realizing the set of capabilities necessary for an NCII. An integrated overall plan, as well as changes in organizational focus, will be necessary to achieve the NCII.

Key problems include, but are by no means limited to, robust wireless communication networks for tactical environments, content-based system resource management, and scalable information dissemination management. Current conceptualizations of the operational and system architectures seem more suited to situations where requirements can be laid out fully in advance of development rather than to the flexible, iterative process necessary for construction of the

TABLE 1.1 Status of Programmed Baseline NCII

|

Capability |

Assessment |

|

Supporting Resource Base |

|

|

Communications and networking |

Significantly increased in-theater SATCOM capacity planned, but stated Department of the Navy capacity requirements could be unrealistically low; only limited improvements in tactical communications planned. |

|

Information assurance |

Basic network security products being deployed; critical vulnerabilities remain to be considered. |

|

System resource management |

Communication channels can be assigned, but priorities cannot be assigned within Internet Protocol (IP) networks. IP advances offer quality-of-service enhancements. |

|

Operational Function |

|

|

Collection management |

Current capabilities are stovepiped by sensor; limited near-term enhancements are planned. |

|

Information exploitation and integration |

Automated extraction of individual targets is accomplished, but much manual work still required for overall battlespace picture. |

|

Information request and dissemination management |

Significant improvements in information location and access are promised by information dissemination management capabilities currently being deployed. |

|

Information presentation and decision support |

Dynamic two-dimensional, map-based displays of friendly and enemy platforms are in development; overall concept for information needed and means to display it still required. |

|

Execution management |

Dynamic mission planning for rapid direction and redirection of forces during operations is limited. |

NCII. Sufficient information was not available to the committee to resolve the matter of communications capacity requirements, but it appears that stated future Navy communications requirements could be unrealistically low, even though the available military and commercial satellite communications (SATCOM) capacity is projected to increase significantly. The appropriate division between military and commercial communications will have to be a topic of continuing analysis, planning, and adaptation as the NCII is built and operated.

However the division between military and commercial communications is made, extensive use of commercial communications infrastructure will be inevitable. As pointed out in the Naval Studies Board's TFNF study,9 this need will

|

9 |

See Footnote 5. |

TABLE 1.2 Some Remaining Challenges in Providing NCII Functional Capabilities

|

Capability |

Challenges |

|

Supporting Resource Base |

|

|

Communications and networking |

Rapid configuration and reconfiguration of networks; flexible wireless networks; multifrequency, electronically steerable antennas. |

|

Information assurance |

Intrusion assessment; intrusion tolerant systems; preventing denial of service; hardening of legacy systems. |

|

System resource management |

Content-based priority management; dynamic allocation of resources. |

|

Operational Function |

|

|

Collection management |

Integration across sensors, with intelligent cross-cueing and dynamic tasking. |

|

Information exploitation and integration |

Automated integration of disparate information; increased automation of feature extraction from images. |

|

Information request and dissemination management |

Profile-based dissemination from large and heterogeneous collections of information sources; automated dissemination management policy. |

|

Information presentation and decision support |

Intuitive situational displays; comprehensive suite of necessary decision-support tools. |

|

Execution management |

Dynamic replanning; real-time simulation. |

be most effectively and economically accommodated by direct use of commercial systems and technology. Such use will require the Navy and Marine Corps to adapt their system design and utilization practices to the demands of the commercial marketplace while ensuring security, priority, and uninterrupted access in times of emergency. Information assurance will be an essential factor in the NCII's evolution and adaptation for network-centric operations.

Finally, it must be noted that efforts to maintain the current distinction between the Joint Planning Network and the Joint Data Network, and likewise to maintain unique protocols for imagery data links, appear not only counterproductive in terms of such factors as interoperability, but also unnecessary in light of developing communications and network technology.

1.4.4 Recommendations Regarding the Design and Construction of the Naval Command and Information Infrastructure

-

The Department of the Navy should develop and enforce a uniform NCII architecture across the strategic, operational, and tactical levels of naval forces.

-

This means that, for all levels, (a) the same set of functions will apply (e.g., as defined in Figure 1.7),10 (b) interfaces and standards associated with these functions will be the same, and (c) consistent definitions will be used for the data exchanged between the functions. Architectural concepts more advanced than the simple standards-based architectures currently being considered should be incorporated into the NCII to realize the flexible, rapidly configurable information support envisioned for network-centric operations. Standards should be imposed at a level that does not inhibit innovation in function or implementation; for example, radio standards should specify waveforms and transport protocols— not implementation details—to permit multiple generations of software radios to interoperate.

-

The Department of the Navy should develop a comprehensive and balanced transition plan for realizing the NCII. The functional architecture shown in Figure 1.7 provides a conceptual framework on which to base the transition plan, and the specific recommendations summarized at the end of Chapters 5 and 6 for each of the functional capabilities provide a starting point for the transition to use of the NCII.

-

The NCII should be developed in coordination and collaboration with the other Services, the joint community, and National agencies to promote interoperability and build on each other's efforts. It should also allow for incorporation of coalition capabilities, as appropriate, to missions involving coalition forces. One specific near-term opportunity for coordinating with other Services would be, for example, through participation in the joint expeditionary force experiments sponsored by the Air Force.

-

The Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, and Acquisition (ASN (RDA)), the CNO, and the CMC should join with the other components of DOD to sponsor a vigorous, continuing R&D program aimed at meeting the challenges of creating an advanced NCII. As part of this effort, the Department of the Navy should give serious attention to the many DARPA and naval research programs that have the potential to meet the challenges.

-

The Department of the Navy should work with the ASD (C3I) and the other Services to make the operational and systems architecture products specified in the C4ISR architecture framework suitable for the flexible and rapidly evolving information support that the NCII must provide.

-

The Department of the Navy should conduct continuing comprehensive analysis of communication capacity requirements and projected availability, and should identify remedial actions if significant shortfalls exist. This analysis should include both long-haul communications and tactical data links, including direct links from in-theater sensors.

|

10 |

The tactical domain will, in addition, have its own unique functions that are particular to warfighting mission areas. These are considered in Chapter 3. |