3

Financing Vaccine Purchase and Delivery

This chapter examines the roles of public and private programs in financing immunization services and purchasing vaccines, which reflect both the strengths and limitations of the nation’s health care financing system. As is true with personal health care generally, immunization coverage policies have changed substantially over the past half-century. Immunizations today represent a significant part of the cost of routine health care for infants and young children. The cost of an immunization reflects both the cost of the vaccine and the cost of administering it (the health professional’s time, supplies, and overhead).1 When an individual needs multiple vaccines over a relatively brief period of time (e.g., a child who has fallen behind in the routine childhood immunization schedule and for whom a “catch-up” schedule is warranted), the cost at the point of service can be considerable.

Immunizations are both a basic public health intervention and a personal health service, benefiting society as well as the protected individual. In contrast with many personal health care interventions, the benefit of immunizations to nearly all individuals is undisputed, and their cost-effectiveness is both documented and widely recognized (Sisk et al., 1997; Cochi et al., 1985; White et al., 1985; Huse et al., 1994; Midani et al., 1995). An additional and relatively unique aspect of immunization services is that, unlike many types of health care, their provision is the subject of widely accepted, evidence-based practice guidelines for both children and adults, promulgated and updated by CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) (see Figure 1–1 and Table 1–3 in Chapter 1).

Despite these national consensus recommendations, however, substantial variations in coverage and payment policies among public and private insurers remain, a consequence of the nation’s multipayer approach to health care.

When there were few recommended vaccines, immunizations were financed as a public health service and were typically delivered by public health agency personnel. Most Americans over the age of 40, for example, can probably recall receiving polio vaccine from a public health nurse, typically at school. As the number and cost of immunizations increased, and as insurance expanded to cover primary and preventive services as well as traditional insurable events, the very concept of immunizations also evolved. Immunizations became less of a public health intervention and became increasingly integrated into comprehensive primary health care.

The sheer magnitude of the modern immunization effort has implications for both health care cost and quality, as well as the protection of the public’s health. Vaccine purchase and service delivery are essential features of the national immunization enterprise, and immunizations are optimally provided within the context of an ongoing primary care relationship. General health care financing provided through employment-based and other private insurance, Medicaid, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), and Medicare aids in integrating immunizations into routine health care. Yet while these private and public health insurance programs account for the majority of immunizations provided nationally, they do not offer the U.S. population seamless and universal coverage. The federal Section 317 categorical grant program and state vaccine purchase and delivery programs address residual needs created by gaps and uncertainties in these health financing plans (see Box 3–1).

Over the past 50 years, public and private insurance initiatives at both the federal and state levels have expanded insurance coverage for immunizations among both publicly and privately insured children. In 15 states, pediatric immunization coverage has been achieved through the establishment of universal, public vaccine purchase programs that distribute vaccines directly to pediatric health care providers. The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, enacted by Congress in 1993, created a similar direct purchase and delivery system for certain children on a nationwide basis.

Despite the fact that vaccine-preventable diseases can be spread by and affect individuals of all ages, finance policy with regard to adult immunization is significantly more limited and uneven. Both public and private insurers are less likely to cover recommended immunizations for adults, and adults are not included in universal state vaccine purchase and distribution systems.

|

BOX 3–1 Examples of Residual Needs That Require State Vaccine Purchase The following are examples of the types of children and adults who require assistance for vaccines purchased with both Section 317 and state-level funds:

|

As with many aspects of American health care financing, it is virtually impossible to determine with any precision the extent to which insured persons are covered for immunizations. The nation’s multipayer insurance system lacks any single cross-payer database that would provide information on the extent of coverage for particular items or services. Although several national probability studies are designed to measure insurance coverage and utilization of health services, none contains sufficiently detailed information to determine immunization coverage by type of insurance.2 Even within classes of public and private insurance (e.g., Medicaid, SCHIP, employer-sponsored plans), insurance coverage levels cannot be documented with accuracy, since plan sponsors (individual state Medicaid agencies or sponsoring employers) typically have significant discretion in formulating coverage and payment policies. Despite the limitations of available data, however, certain trends and patterns of coverage can be identified. The first three sections of this chapter examine immunization coverage and payment policies under private health insurance; Medicaid, SCHIP, and VFC; and Medicare. The fourth section reviews vaccine purchase grants under Section 317, while the fifth examines state vaccine purchase policies. The final section addresses current issues in vaccine purchase policy.

PRIVATE INSURANCE COVERAGE OF IMMUNIZATION

In 1998, 227 million Americans had some form of public or private health insurance. Yet more than 44 million people, one-fourth of them children, were uninsured (see Table 3–1). As Table 3–1 shows, about three-fourths of those with private health insurance obtain that insurance through employer-sponsored health plans.

By 1999, 28 states had enacted laws requiring insurers to cover childhood immunization services to at least some degree (Freed et al., 1999). As with any type of state insurance regulation, coverage standards vary considerably from state to state. For example, a state law might:

-

Regulate the scope of coverage, requiring that insurers cover immunizations in accordance with ACIP standards or refer to the standards endorsed by a professional society, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics.

-

Prohibit deductibles or coinsurance, resulting in what is called “first-dollar” coverage for immunizations.

-

Fashion less specific standards, simply requiring that insurers cover “appropriate” pediatric vaccines, with decisions regarding which vaccines to include or the nature of any cost sharing left to the discretion of the insurer.

TABLE 3–1 U.S. Population Health Insurance Coverage, 1998

|

Population Group |

Number (in thousands) |

Percentage |

|

All persons |

271,743 |

|

|

Not covered |

44,281 |

16.3 |

|

Total covered |

227,462 |

83.7 |

|

Private |

190,861 |

70.2 |

|

Employer-based |

168,576 |

62.0 |

|

Government |

66,087 |

24.3 |

|

Medicare |

35,887 |

13.2 |

|

Medicaid |

27,854 |

10.3 |

|

Military |

8,747 |

3.2 |

|

All children (under 18 years of age) |

72,022 |

|

|

Not covered |

11,073 |

15.4 |

|

Total covered |

60,949 |

89.6a |

|

Private |

48,627 |

67.5 |

|

Employer-based |

45,593 |

63.3 |

|

Government |

16,400 |

22.8 |

|

Medicare |

325 |

0.5 |

|

Medicaid |

14,274 |

19.8 |

|

Military |

2,240 |

3.1 |

|

Poor children (under 18 years of age)b |

13,467 |

|

|

Not covered |

3,392 |

25.2 |

|

Total covered |

10,075 |

74.8 |

|

Private |

3,059 |

22.7 |

|

Employer-based |

2,586 |

19.2 |

|

Government |

7,955 |

59.1 |

|

Medicare |

135 |

1.0 |

|

Medicaid |

7,784 |

57.8 |

|

Military |

223 |

1.7 |

|

aSome individuals have multiple sources of coverage (e.g., Medicare and private insurance, or Medicaid and Medicare). Thus the percentages add to more than 100. bChildren in families with incomes of less than 100 percent of the federal poverty line. SOURCE: Bureau of the Census, 1999. |

||

Employers that self-insure are generally exempt from state insurance regulation under the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA).3 Approximately 50 million privately insured individuals are covered by self-insured plans, and this limits the reach of state insurance laws or regulations governing the coverage of pediatric vaccines (Copeland and Pierron, 1998; Polzer, 2000).

Other federal legislation, however, prohibits employers (regardless of whether they purchase insurance or self-insure) from reducing “cover-

age of pediatric vaccines (as defined under [the Medicaid program]) below the coverage…provided as of May 1, 1993."4 Thus, employers that provided any vaccine coverage as of that date must continue to provide such coverage. This “maintenance-of-effort” provision was aimed at preventing employer-sponsored plans from reducing coverage following enactment of the VFC program. While the statute does not require a particular level of coverage and does not specify standards regarding deductibles and cost sharing, it establishes some federal standards with respect to childhood immunizations.5

There are few data available on insurance practices with respect to immunizations. One national survey of employer-sponsored health coverage reports that coverage of childhood immunizations is common, but it does not provide detailed information about the nature of the coverage, e.g., whether it meets the ACIP standard or whether deductibles and copayments apply (KPMG Peat Marwick, 1998) (see Table 3–2). The results of this survey support an estimate that 92 percent of all children covered by employer-sponsored plans, or 42 million children, have some coverage for immunizations.6

Researchers at The George Washington University collected data on the immunization coverage policies of five health care companies (four national and one regional) that suggest significant variation by type of plan, as well as by vaccine (S.Rosenbaum, The George Washington University, personal communication, February 8, 2000). Consistent with the KPMG study, the respondents indicated that coverage varies by type of product. All five companies reported that they generally would cover

TABLE 3–2 Coverage of Pediatric Immunizations by Health Benefit Plans Offered by Employersa

|

Type of Insurance Product |

Percentage of Covered Workers with Each Type of Productb |

Percentage of Employees with Dependent Coverage for Pediatric Immunization Servicesc |

|

Health Maintenance Organizations |

28 |

99 |

|

Point-of-Service Plans |

25 |

98 |

|

Fee-for-Service Plans |

9 |

79 |

|

Preferred Provider Organization Plans |

38 |

86 |

|

aInsurance coverage does not mean that children actually get vaccinated. bSOURCE: Health Research and Educational Trust, 1999. cSOURCE: KPMG Peat Marwick, 1998. |

||

diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP); Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib) conjugate; hepatitis B; measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR); oral poliovirus (OPV); and varicella. However, coverage was more variable for other pediatric vaccines.7 Respondents did not indicate whether their coverage was consistent with ACIP standards, nor did they report their cost-sharing policies.

The five companies reported more limited coverage of immunizations for adults. Three reported typical coverage of rubella vaccine for persons aged 25–65, two reported coverage of varicella for working-age adults, and three reported coverage of tetanus and diphtheria toxoids. Three companies reported covering influenza and pneumoccocal vaccines for enrollees over age 65, but not for younger adults.

Capitated managed care plans may realize savings from immunizing elderly and at-risk younger adults for influenza and pneumococcal disease, and are more likely than traditional indemnity insurance plans to cover and actively promote these immunizations. However, no systematic surveys of the extent of such coverage have been conducted.

Finding 3–1. While most private health plans provide some form of immunization coverage, this coverage varies by type of plan, as well as by vaccine. Enrollment in a private plan does not guarantee that immunizations will be provided as a plan benefit.

MEDICAID, VACCINES FOR CHILDREN, AND STATE CHILDREN’S HEALTH INSURANCE PROGRAM

Medicaid and Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment Program

Medicaid, the nation’s largest public insurance program for low-income and medically indigent persons, covered an estimated 31 million people in 1998, more than half of whom were children (Health Care Financing Administration, 2000c, 2000d). An additional estimated 4.7 million children aged 18 or younger who lacked health insurance and were eligible for Medicaid were not enrolled in it (Selden et al., 1998).

In 1967, 2 years after its inception, Medicaid was expanded to include comprehensive primary health care for children under age 21 through the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment Program (EPSDT).8 Since then, Medicaid has been a significant source of funding (federal and state) for immunizations, and since 1979, immunizations have been a mandatory service for eligible children. Amendments to the Medicaid law in 1989 specifically codified immunizations as a mandatory component of the Medicaid program for individuals under age 21 and

specified coverage in accordance with ACIP standards.9 Federal Medicaid policy prohibits the imposition of cost sharing for enrollees under age 18; the extent to which states impose cost sharing for immunizations in the case of persons aged 18–21 remains uncertain. States have the option of covering all routine and risk-related ACIP-recommended immunizations for Medicaid-enrolled adults (both elderly and nonelderly), but the extent of state coverage for adult immunizations is not known.

Prior to VFC, Medicaid paid for both vaccines and administration fees. Estimates of Medicaid program expenditures for immunization services were $364 million in fiscal year (FY) 1994, the last year before implementation of VFC; $200 million of this total was federal costs, and the remainder was state Medicaid matching costs (information provided by CDC). In FY 1998, when VFC spending for vaccines and operational costs was $437 million, Medicaid program expenditures—largely for administration fees, but including some vaccines not covered by VFC—were $127 million, $70 million of which was federal (see Table 3–3) (information provided by CDC).

Vaccines for Children Program

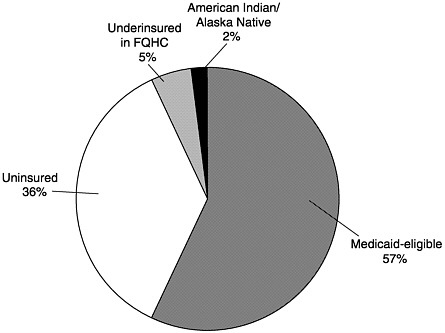

In 1993 Medicaid was further amended to include the VFC program, which is 100 percent federally financed.10 The program creates a federal entitlement to immunization services for children aged 18 and under who are (1) Medicaid-eligible, (2) uninsured, (3) underinsured and receiving immunizations through a federally qualified health center (FQHC) or rural health clinic, or (4) Native American or Alaska Native.11Figure 3–1 displays the share of VFC spending represented by each eligibility group. Notably, the legislation establishing the VFC program explicitly prohibits spending on program administration except for narrowly defined operational costs associated with ordering, inventory maintenance, distribution of vaccines, and provider enrollment and coordination.12

The VFC program requires the Secretary of Health and Human Services to negotiate vaccine purchase agreements with manufacturers. VFC vaccines are available only when administered by “program-registered” providers.13 In 1998, an estimated 44,000 public and private providers were eligible to receive VFC vaccines (information provided by CDC). The VFC legislation requires “maintenance-of-effort” by states, similar to the maintenance-of-effort provision for employer-sponsored health plans included in ERISA. The law provides that, as a condition of receipt of vaccine under VFC, states must agree to maintain their insurance laws governing immunization coverage at 1993 levels.14

The VFC program does not change the states’ basic obligation to cover all ACIP vaccines for Medicaid children. Significant delays can occur,

however, between the adoption of a new vaccine by ACIP and the completion of federal contract negotiations between CDC and the vaccine manufacturer. For example, an 11-month delay occurred between the time that varicella vaccine was recommended by ACIP (June 1995) and the effective date of VFC coverage (May 1996) (N.Smith, CDC, personal communication, February 10, 2000). In the absence of a VFC contract, state Medicaid agencies must directly cover all ACIP-recommended vaccines as a basic EPSDT service, paying commercial price for the vaccine and sharing the cost of the purchase at the usual Medicaid matching rate. Furthermore, since VFC covers children aged 18 and younger, states remain responsible for the immunization of adolescents aged 18–21 who are enrolled in Medicaid. In sum, the VFC program has reduced, but not eliminated, states’ financial obligations with respect to coverage of immunizations for Medicaid-enrolled children.

State Children’s Health Insurance Program

SCHIP, enacted in 1997, provides states with “child health assistance” to extend services to “targeted low-income” children who are ineligible for Medicaid but otherwise uninsured.15 Unlike Medicaid (including the VFC program), which creates a federal entitlement to coverage and is financed on an open-ended basis, SCHIP is a block grant program subject to aggregate federal payment limits.16 The federal SCHIP allotment formula is more generous than the Medicaid federal financing scheme: the SCHIP state matching requirement is 70 percent of the state’s Medicaid matching rate.

States have the discretion to use their annual SCHIP allotments to expand Medicaid; create separate, freestanding children’s insurance programs; or design a combination of the two. As of January 2000, 33 states had used their SCHIP allotments in whole or in part to establish freestanding programs (see Table 3–4).

To the extent that states use their SCHIP allotments to expand Medicaid, all Medicaid coverage requirements apply. As with other Medicaid-covered children, those whose enrollment is purchased with federal SCHIP funds are entitled to the full EPSDT benefits, including vaccines purchased through the VFC program.

In the case of freestanding SCHIP programs, immunizations are a mandatory service, and coverage is set according to ACIP standards.17 However, SCHIP children enrolled in freestanding programs are not entitled to receive vaccines through the VFC program. States are required to cover vaccines and their administration for children in freestanding SCHIP programs as part of their annual federal SCHIP allotment. States may, however, purchase these vaccines through the federal VFC contract

TABLE 3–3 Medicaid and Vaccines for Children (VFC) Program, FY 1994–1999 (millions of dollars)

|

Program |

FY 1994 Actualc |

FY 1995 Enacted |

FY 1995 Actual |

FY 1996 Enacted |

FY 1996 Actual |

|

|

VFC Program |

||||||

|

Vaccine purchase |

20.9 |

20.9 |

412.0 |

213.8 |

349.3 |

254.9 |

|

Operations |

3.8 |

3.8 |

45.3 |

29.8 |

24.7 |

24.7 |

|

Total |

24.7 |

24.7 |

457.3 |

243.6 |

374.0 |

279.6 |

|

Medicaid |

|

200.0 |

140.0 |

140.0 |

60.0 |

60.0 |

|

TOTAL |

|

224.7 |

597.3 |

383.6 |

434.0 |

339.6 |

|

aIn FY 1994, $80 million was awarded for phase 1 operations and vaccine purchase. bThe enacted level is the amount requested in the president’s budget. cActual expenditures. |

||||||

FIGURE 3–1 Children receiving VFC vaccines by eligibility category, calendar year 2000 (estimated). SOURCE: Information provided by CDC.

|

FY 1997 Enacted |

FY 1997 Actual |

FY 1998 Enacted |

FY 1998 Actual |

FY 1999 Enacted |

FY 1999 Actual |

FY 2000 Estimate |

|

498.6 |

351.0 |

408.5 |

388.6 |

526.9 |

434.9 |

504.2d |

|

25.4 |

24.7 |

28.6 |

29.6 |

39.4 |

32.6 |

40.9d |

|

524.0 |

375.7 |

437.1 |

418.2 |

566.3 |

467.5 |

545.1 |

|

65.0 |

65.0 |

70.0 |

70.0 |

75.0d |

75.0d |

80.0d |

|

589.0 |

440.7 |

507.1 |

488.2 |

641.3 |

542.5 |

625.0 |

|

dProjection. SOURCE: Information provided by CDC. |

||||||

(Richardson and Orenstein, 1999). Thus states with freestanding SCHIP programs maintain some level of financial exposure for the cost of immunization services.

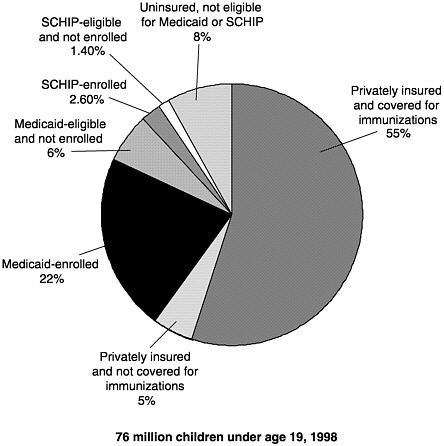

Figure 3–2 shows the combined potential reach of Medicaid, the VFC program, and SCHIP. Assuming full coverage of all eligible children, Medicaid and SCHIP would reach about one-third of all American children aged 18 and under.18 The addition of VFC entitlement for non-Medicaid children increases by another 6 million the number of children

TABLE 3–4 State Children’s Health Insurance Programs, 2000a

FIGURE 3–2 U.S. children’s insurance coverage for immunizations. SOURCES: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey estimates of those Medicaid-eligible and enrolled, and SCHIP-eligible (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 1996); SCHIP enrollment (Health Care Financing Administration, 1999b); U.S. Bureau of the Census 1998 population estimates; private insurance coverage for immunizations (KPMG Peat Marwick, 1998).

entitled to vaccine coverage as a matter of federal law.19 Thus as of 1999, federal policies allowed for the potential coverage of roughly 30 million children for immunization services.

SCHIP enrollment had reached a total of almost 2 million children by September 30, 1999, double the number covered in the first full year of the program, calendar year 1998 (Health Care Financing Administration [HCFA], 1999b). States have streamlined applications for SCHIP and increased outreach efforts. An additional 600,000 to 1.1 million children are eligible for SCHIP but not covered, according to projections based on the

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (Selden et al., 1999). In some states, Medicaid enrollment has increased as a result of SCHIP outreach efforts (HCFA, 1999a). Finally, 23 states offer 12-month continuous eligibility in their separate SCHIP programs, as do 15 states for Medicaid (HCFA, 1999a). This longer minimum eligibility period should improve the continuity of primary care, including immunizations, received by enrolled children. Table 3–5 summarizes federal coverage policies for children under Medicaid, VFC, and SCHIP.

Enrollment in Medicaid in particular remains below the potential reach of the program, however, with 22 percent of all eligible children (4.7 million out of 21.2 million) not enrolled (Selden et al., 1998). This underenrollment appears to be the result of many factors, ranging from a lack of awareness of programs on the part of families to systemic barriers that make enrollment difficult (Ellwood, 1999).

Managed Care and Medicaid, VFC, and SCHIP

In 1998, all but four states mandated enrollment in managed care by some or all Medicaid beneficiaries as a condition of coverage for at least a portion of Medicaid benefits (information provided by HCFA). As of 1998, 16.6 million Medicaid enrollees (54 percent of the total), were enrolled in some form of managed care arrangement, a more than three-fold increase in Medicaid managed care enrollment since just 1993 (information provided by HCFA).

Freestanding SCHIP programs often involve managed care arrangements, with providers or provider groups, such as independent practice associations, being “at risk” for the services used by their enrollees. Because children enrolled in freestanding SCHIP programs are “insured” and therefore not eligible for VFC vaccines, the capitation rates paid to SCHIP plans ostensibly cover both the cost of purchasing required vaccines and the cost of administering them, unless the state makes other arrangements (see Box 3–2). In California, a state with a combination SCHIP program, some providers argue that the capitation rates in the freestanding SCHIP plans are set too low to compensate them for vaccine purchases, and some capitated providers have referred patients to public health clinics to receive free vaccinations (Fairbrother et al., forthcoming).

States that require beneficiaries to enroll in a managed care plan may require these plans to provide additional benefits and services not normally offered to Medicaid beneficiaries receiving care in the fee-for-service system.20 Thus even if immunizations were not otherwise covered for adults, a state Medicaid agency could specify such coverage in its managed care service agreements.

Very limited information is available on the extent of adult immuni-

TABLE 3–5 Federal Immunization Coverage Policies for Children Under Medicaid, Vaccines for Children (VFC), and State Children’s Health Insurance Programs (SCHIP)

|

Program |

Eligibilitya |

Federal Financing |

|

Medicaid |

Children up to age 6:133% FPLb |

50–78% |

|

|

Children aged 6–18:100% FPL (through age 21 in the EPSDTc program) |

|

|

|

State option to cover additional children up to state-defined eligibility levels |

|

|

VFC |

Children aged 0–18 who are: Medicaid-eligible Uninsured Native American/Alaska Native Underinsured |

100% 100% 100% Only if vaccinated at FQHCsd |

|

SCHIP (Medicaid) |

State sets level using Medicaid coverage flexibility |

Enhanced FFPe (65–85%) |

|

SCHIP (freestanding) |

Children with incomes above Medicaid but<50% over Medicaid eligibility levels who are uninsured and ineligible for Medicaid |

Enhanced FFP (65–85%) |

|

aThe Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices establishes general vaccine schedule recommendations and then prepares a separate resolution for coverage through the VFC Program. CDC publishes the recommendations and negotiates a vaccine contract(s). Funds are awarded to the states, and the vaccine is purchased and supplied by the states to health care providers. bFederal poverty level. cEarly and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment Program. dFederally qualified health center. eFederal financial participation. SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, 2000c. |

||

zation coverage under Medicaid managed care. A study of contracts between state Medicaid agencies and managed care organizations furnishing comprehensive services revealed that 19 standard contracts in effect as of January 1998 specified coverage of immunizations for adults (Rosenbaum et al., 1998). All contracts specified coverage of childhood immunizations, although the nature of the specifications ranged from

|

BOX 3–2 New Jersey: Carving the Vaccine Administration Fee Out of Capitation Rates New Jersey has designed “NJ KidCare,” its mixed-model SCHIP, to be as seamless as possible, from both the providers’ and the patients’ point of view, across its Medicaid expansion program and three additional freestanding plans. Immunization payment policy is the same for all children in either Medicaid or NJ KidCare. Children in Medicaid receive vaccines from VFC. The state uses a portion of its state SCHIP contribution to purchase vaccines at the CDC contract price for distribution to all physicians in the three freestanding SCHIP plans. Thus physicians receive vaccines up front for all children in state-sponsored insurance programs. Physicians in New Jersey participate in Medicaid/SCHIP largely through the six managed care organizations (MCOs) with which the state contracts. Instead of allowing these MCOs to capitate primary care providers for the provision of immunizations to their pediatric patients, New Jersey has negotiated with them to “pass through” the state’s vaccine administration fee of $11.50, which the state built into the MCOs’ actuarially-based capitation payments. To receive this fee, providers must send the MCO a notice of the immunization, essentially a bill for rendering the service. Not only does the payment encourage providers to immunize, but it also improves the reporting and documentation of immunizations delivered for the MCOs, which can build their HEDIS reports from these notices. |

language that paralleled federal requirements (e.g., coverage at the ACIP level) to broader specifications.

Finding 3–2. Medicaid, VFC, and SCHIP are important components of the national immunization effort, with the potential to finance immunizations for more than one-third of the nation’s children. Yet eligibility for any of these programs does not guarantee enrollment, and enrollment does not guarantee the receipt of up-to-date immunizations. Medicaid eligibility is determined monthly in most states, and discontinuities in coverage interfere with timely immunization. SCHIP has expanded access to primary health care, including immunizations, for a growing number of uninsured children. However, the administrative requirements of this program have added new complexities to vaccine purchase and delivery that require additional oversight, monitoring, and compliance activities on the part of state public health agencies. Because of the scale of the VFC program and the narrow statutory definition of administrative costs for that program, states must draw upon Section 317 grants and state revenues to implement the VFC effort fully in public and private health care settings.

MEDICARE

Medicare is a completely federal social insurance program that entitles eligible persons to coverage for a defined set of benefits, including certain immunizations.21 All Medicare-eligible individuals enrolled in Part B of the program, whether entitled to coverage on the basis of age, disability, or coverage for end-stage renal disease (ESRD), are entitled to immunizations for influenza and pneumococcal disease, as well as for hepatitis B if determined to be at risk for that disease. Since the original 1965 Medicare statute excluded coverage of all preventive services, other vaccines or inoculations are excluded as “preventive immunizations” unless directly related to the treatment of an injury or direct exposure to diseases or conditions.22 Pneumococcal and influenza immunizations are covered by Medicare without deductible and coinsurance.

In 1998, 32.3 million persons aged 65 and older were covered by Medicare Part B. An additional 5 million persons under age 65 were covered as disabled or ESRD beneficiaries. Originally designed in 1965 as a health insurance program to cover the expenses of acute and rehabilitative medical care, Medicare explicitly excluded coverage of preventive services until Congress authorized the coverage of pneumococcal vaccine in 1981. In 1984, hepatitis B vaccine was covered for ESRD patients, and it is now covered for any beneficiaries who are at risk of the disease. Annual influenza immunizations were added to Medicare benefits in 1993, following a 4-year demonstration program. In 1994, the first full year in which both influenza and pneumococcal vaccines were covered, Medicare spent an estimated $100 million on the vaccines and their administration (General Accounting Office, 1995b). In 1998, Medicare paid providers $87 million for influenza immunizations, $27 million for pneumococcal immunizations, and $800,000 for hepatitis B immunizations (information provided by HCFA).

Medicare began paying providers a separate fee for vaccine administration as a uniform national policy in 1993. Prior to that time, payment for immunizations was inconsistent among Medicare administrative areas, and sometimes only the cost of the vaccine was reimbursed. As for other physician service payments, Medicare’s vaccine administration payment rates vary geographically.23 For the year 2000, vaccine administration fees range from a low of $3.95 in Mississippi to a high of $5.38 in New York City, with a national average of $4.39 (information provided by HCFA).

Some have argued that Medicare administration fees are too low to compensate physicians adequately for the costs of storing and administering vaccines, and that these low fees contribute to low immunization coverage rates among beneficiaries (Poland and Miller, 2000). However, other factors contribute to low influenza and pneumococcal coverage rates for the elderly, including provider practices and knowledge, and patients’

beliefs about and understanding of the relative risks and benefits of immunization for these diseases. Coverage of persons aged 65 and older for influenza vaccine climbed steadily during the past decade, from 42 percent in 1991 to 63 percent in 1997 (see Table 3–6). The cumulative (ever vaccinated) coverage levels for pneumococcal vaccine for the elderly between 1991 and 1997 doubled from 21 to 42 percent (see Table 3–6). Yet racial and ethnic disparities in immunization rates for the elderly have persisted. In 1997, the influenza immunization rate for elderly blacks was just two-thirds that for whites (45 as compared with 66 percent), and the pneumococcal immunization rate for both blacks and Hispanics was half that for whites (22–23 percent as compared with 46 percent). For noninstitutionalized high-risk adults aged 18–64 (often those with chronic illness such as heart and lung disease or diabetes), coverage rates in 1997 for influenza vaccine were 47 percent for those with Medicare (disabled or ESRD beneficiaries), 29 percent for those with private insurance, and 14 percent for those without insurance. Pneumococcal vaccine coverage rates for high-risk adults aged 18–64 were 28 percent for those with Medicare, 12 percent for those with private insurance, and 10 percent for those without insurance (see Table 3–6).

The number of adults aged 18–65 who are at high risk of complications from influenza and pneumococcal disease, for whom immunization is strongly recommended, is roughly 26 million (11 percent of those aged 18–44 and 24 percent of those aged 45–64 have chronic conditions that put them at risk) (Singleton et al., forthcoming). Of these, about one-fifth, or 5 million high-risk nonelderly adults, lack health insurance, and thus have no coverage for these immunizations. As noted earlier, there is very little information on the extent to which private health plans cover adult immunizations. Although the extent of the high-risk population facing financial barriers to receiving immunizations cannot be estimated precisely, the number is likely to be substantially greater than the 5 million who are completely uninsured (see Box 3–3).

As with Medicaid managed care, Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare+Choice plans may qualify for additional benefits, including all routine or recommended immunizations. As of February 2000, 6.8 million Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in prepaid managed care plans— almost five times as many as were enrolled in 1991 (information provided by HCFA).24 With increasing numbers of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in managed care, the program costs for immunizations cannot be determined separately, nor can immunization coverage levels be estimated from billing records, as such records are not available for prepaid plan enrollees. Adult influenza coverage levels are currently a Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS)-reported measure, however, and pneumococcal coverage levels may be added in the near future (Poland

TABLE 3–6 Influenza and Pneumococcal Immunization Rates (percent coverage)

|

|

1991 |

1993 |

1995 |

1997 |

||||

|

Population Group |

Influenza |

Pneumococcal |

Influenza |

Pneumococcal |

Influenza |

Pneumococcal |

Influenza |

Pneumococcal |

|

Adults≥65 years old |

42 |

21 |

52 |

28 |

58 |

34 |

63 |

42 |

|

White |

|

61 |

36 |

66 |

46 |

|||

|

Black |

27 |

14 |

33 |

14 |

40 |

22 |

45 |

22 |

|

Hispanic |

34 |

12 |

47 |

13 |

50 |

23 |

53 |

23 |

|

Noninstitutionalized High-Risk Adults |

||||||||

|

Aged 18–64 |

26 |

13 |

||||||

|

White |

|

27 |

13 |

|||||

|

Black |

|

22 |

13 |

|||||

|

Hispanic |

|

19 |

9 |

|||||

|

Private health insurance |

|

29 |

12 |

|||||

|

Medicare |

|

47 |

28 |

|||||

|

Medicaid |

|

26 |

16 |

|||||

|

Medicare and Medicaid |

|

45 |

25 |

|||||

|

No health insurance |

|

14 |

10 |

|||||

|

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, 1997. |

||||||||

|

BOX 3–3 Calculating the Size of the Adult Population That Relies on State-Purchased Vaccines No national survey data are available on which to base estimates of the number of privately insured adults between the ages of 18 and 65 who have coverage for immunizations. Consequently, the following estimate of the demand for pneumococcal and influenza vaccines from public health departments is based only on estimates of the uninsured working-age adult population, and does not reflect any low-income underinsured adults, who also may depend on public clinics for free immunizations. ACIP recommends immunization against pneumococcal disease and influenza for adults under age 65 with heart disease, chronic respiratory system conditions, and diabetes, and influenza vaccine for all those age 50 and older. An estimated 11 percent of the population aged 18 through 49 have these conditions, as do an estimated 24 percent of the population aged 50 through 64 (Singleton et al., forthcoming). Applying these risk rates to 26.6 million uninsured adults aged 18 through 49 and 6.2 million uninsured adults aged 50 through 64, respectively, yields a total of 4.4 million at-risk working age adults without health insurance. Adding in all other uninsured persons (those without these chronic conditions) between ages 50 and 65 would double the demand for annual influenza immunizations to 9 million uninsured persons. The public purchase price of influenza vaccine is $2.15 per dose. The annual cost of purchasing vaccines for the groups for which immunization is recommended by ACIP who are uninsured and aged 18 through 64 is thus $19 million. The public purchase price for pneumococcal vaccine is $5.50. The one-time cost of immunizing the 4.4 million at-risk uninsured adults is thus about $24.2 million. |

and Miller, 2000). Health plans’ internal tracking and reporting systems for immunizations become more important for population surveillance as less information can be gleaned from third-party billing records.

Finding 3–3. The Medicare program has become the single most important source of financing and service delivery for adult immunization efforts over the past decade, and coverage rates for influenza and pneumococcal vaccines have shown significant increases during this period. Yet these coverage levels remain far below recommended levels, especially for racial and ethnic minorities.

SECTION 317 VACCINE PURCHASE GRANTS

Prior to the implementation of VFC in 1994, Section 317 was the major source of support for public vaccine purchase. Historically, the program’s

emphasis has been on pediatric immunization, but use of Section 317 funds for adolescents and adults has been permitted since 1994. Section 317 currently supports 64 state, territorial, and municipal health agency immunization programs. These funds enable grantees to purchase vaccines and ensure that other basic functions of an immunization program are carried out.

The Section 317 program supports national-level and centrally operated CDC programs, as well as state grants. Under the category of program operations, CDC develops national goals, plans and assesses strategies for reaching these goals, negotiates consolidated vaccine purchase contracts, provides surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases and technical assistance to state and local health agencies, and conducts vaccine safety activities. CDC also engages in international eradication efforts targeting polio, measles, and other vaccine-preventable diseases, which account for a growing share of Section 317 funding.

Section 317’s discretionary grants to states take two forms: (1) Direct Assistance (DA), which amounts to a line of credit with CDC for the purchase of vaccines as needed, salaries of federal public health personnel who work within state agencies, and support for immunization registries, and (2) Financial Assistance (FA), which the states may use for programmatic activities such as outreach, disease surveillance and outbreak control, professional and public education, and immunization assessment. Legislative history clearly reflects that the 317 program was intended to supplement state and local immunization efforts; grantees are specifically prohibited from using federal grant funds to replace existing state spending on immunization programs.

The level of funding for the Section 317 program is set through annual federal appropriations, and both the total appropriation and the distribution of awards among the states and local grantees are discretionary. The total appropriation is determined by Congress and the individual grant amounts by CDC. Unlike two other major state grant programs that focus on child health—the Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant and SCHIP—Section 317 awards involve no federal formula and require no financial matching of federal grants with state funds.

Historically, CDC’s annual budget request for the Section 317 program has tracked the level of funds appropriated in the previous year. Although it is not an explicit program standard, by the early 1990s CDC had articulated Section 317’s programmatic responsibility as the financing of vaccines for roughly half of all children served in the public sector (Kelley et al., 1993). Those children dependent on the public sector for immunizations were estimated to comprise 25 to 30 percent of the national birth cohort, just slightly less than the fraction estimated for the initial polio vaccine program in the 1950s. States and localities were expected to

finance immunizations for the remaining half of the children dependent on public-sector services, roughly 12 to 15 percent of their annual birth cohort.

The programmatic objectives of the National Immunization Program administered by CDC are described as follows:

A goal of the Immunization Grant Program has always been to help ensure that the Nation’s citizens have access to and receive all appropriate, routinely recommended vaccines. Throughout the existence of the Program, vaccines for use in the public sector have been purchased with a combination of Federal, State and local funds…. overall, the 317 program purchased 50–60 percent of vaccines used in the public sector [prior to VFC]. However, CDC never intentionally established a “goal” of purchasing 50–60 percent of the public sector need. This proportion was arrived at through a combination of circumstances, including what States were able to contribute, which vaccines the 317 funds were buying (usually the higher-priced and newer products), and available appropriations (information provided by CDC).

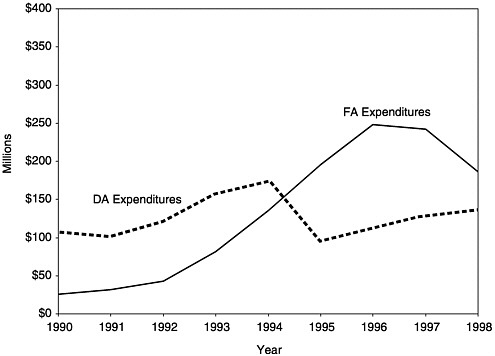

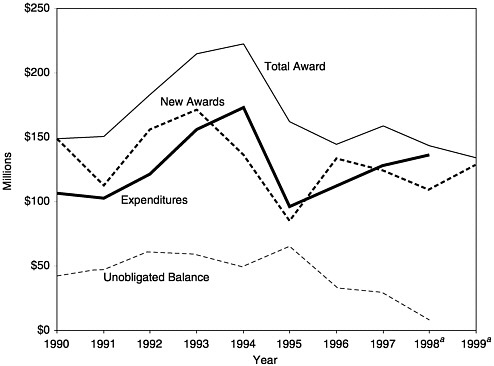

In the early years of the program, Section 317 grants for vaccine purchase (DA) and program administration (FA) were roughly equivalent. Over time, however, as vaccine costs rose and the schedule of recommended vaccines increased, vaccine purchase accounted for a higher proportion of total funds received (Kelley et al., 1993). This balance within the Section 317 program shifted once again after the VFC program became operational in October 1994 and relieved many of the demands on states’ 317 DA grants for pediatric vaccines (see Figures 1–3, 3–3, 3–4, and Appendix F).

Since 1994, at the direction of the Senate Appropriations Committee, CDC has reserved $33 million in FA funds each year for incentive awards to grantees with the highest immunization coverage rates, as measured by the National Immunization Survey (NIS) for 2-year-olds who are up to date with the 4:3:1 immunization series (four DTP, three polio, and one measles). Variable bonuses are available on a per child basis, according to the grantee’s completion rate. As the FA grants have declined over the past 5 years, these incentive funds have become an increasingly larger proportion of overall infrastructure funding, representing 28 percent of new FA funds awarded in 1998.

Finding 3–4. The Section 317 vaccine purchase program allows states to purchase vaccines for administration to disadvantaged populations in a timely manner and to avoid missed opportunities when no other coverage is available to support immunization services. Section 317 infrastructure grants also provide funds for service delivery in the public health sector, and afford state immunization programs swift access to

FIGURE 3–3 Section 317 Direct Assistance and Financial Assistance expenditures by grantees, 1990–1998. SOURCE: Information provided by CDC.

newly licensed vaccines at reduced cost. As of January 2000, VFC had become the primary source of funding for public vaccine purchase. However, states continue to use Section 317 funds to address residual needs as part of their safety net role. The dynamics of how states identify and respond to these needs, using federal or state funds, are not well characterized in the research literature.

STATE VACCINE PURCHASE

When immunizations were limited in number and furnished as a nominal-cost public health benefit, the issue of immunization financing was not significant. As the scope of required immunizations has grown and costs have increased, however, serious tensions have emerged that warrant greater scrutiny. Prior to VFC, private health plans and families paid for most of the immunizations provided in private health care settings, although some private providers immunized children covered by Medicaid. Families that were uninsured or underinsured generally received their immunizations in public health clinics, financed by state revenues and Section 317 funds.

FIGURE 3–4 Total Section 317 Direct Assistance awards, expenditures, and balances, 1990–1999. aEstimated. SOURCE: Information provided by CDC.

Today, the purchase of childhood vaccines is a major component of all state immunization programs. The relative contribution of VFC, Section 317, and state revenues to public vaccine purchase depends on the level of each state’s needs, as well as the particular constellation of immunization financing policies and service-delivery mechanisms (see Box 3–4). States are highly variable in the extent to which they use state revenues for vaccine purchase. Estimating the state-funded share of publicly purchased vaccines in each state from records of expenditures for all vaccines purchased under federal discounted price contracts yields the following results:

-

24 states plus the District of Columbia provide less than 10 percent of publicly purchased vaccines in their jurisdiction,

-

16 states contribute between 10 and 30 percent of publicly purchased vaccines, and

-

10 states contribute 30 percent or more of all publicly purchased vaccines.

|

BOX 3–4 Calculating the Size of the Child Population That Relies on State-Purchased Vaccines Almost 600,000 children (15 percent) among the annual birth cohort of 3.88 million children in the United States lack health insurance, and an additional 1.2 million (31 percent) are enrolled in Medicaid plans.1 The committee estimates that the majority within this combined national population of 1.8 million infants (80 percent, or 1.44 million) are served by public and private health care providers that rely on VFC vaccines or SCHIP funds to serve their patients. This calculation leaves a residual need for the population of at-risk children (20 percent of 1.8 million, or 360,000 infants) who for some reason are not identified as VFC-eligible, or who otherwise depend on vaccines provided by local health clinics that are commonly purchased with Section 317 or state funds.2 An additional group of children (the “underinsured”) are enrolled in private health plans that lack coverage for vaccines. An estimated 8 percent of families with private health insurance do not have coverage for childhood immunizations (KPMG Peat Marwick, 1998). Their providers often refer them to local health clinics if they cannot cover vaccine costs out-of-pocket, but these children are not eligible for VFC, unless seen in federally qualified health centers, because they are insured. This population is estimated to represent between 4 and 5 percent of the annual birth cohort, or 170,000 infants. The combination of 360,000 children who are eligible for but do not have access to the VFC/SCHIP programs and the 170,000 children who have private insurance but lack vaccine coverage totals 530,000 children (about 14 percent of the annual U.S. birth cohort) who rely on Section 317 or state-purchased vaccines for their immunization needs. This is one component of the safety net population commonly served by public health clinics. Other components include recent immigrants who have not yet met residency requirements that qualify them for Medicaid or SCHIP assistance, and adults aged 18 to 65 who do not have access to vaccines (see Box 3–3). Immunization costs for children in the first 2 years of life are estimated at $400 (including $175 for vaccine purchase at federal contract rates [and not including pneumococcal conjugate], plus $225 in vaccine administration fees [$15 times 15 antigens]). Multiplying this $400 total immunization cost times the estimated 530,000 residual needs population derived above generates a total annual requirement of $212 million for early childhood vaccines alone. Special note: An additional population that may be served by public health clinics deserves consideration in this discussion. In many communities, children who are enrolled in a Medicaid or SCHIP managed care plan request immunizations from their local public health clinics either because they have difficulty scheduling appointments with their own providers, because their providers are not participating in the VFC program, because they are responding to certain local outreach initiatives, or because of other special circumstances. However, the managed care plans in most states are priced to include the cost of purchasing and administering vaccines within the early childhood schedule. Several states and communities have successfully negotiated contracts that allow their public health clinics to bill |

Nationally, state vaccine purchases account for 12 percent of all expenditures under the federal contract; VFC accounts for 65 percent, and Section 317 for 22 percent (information provided by CDC).

Since the inception of VFC, state approaches to vaccine purchase and immunization delivery have fit one of three models: VFC only, enhanced VFC, or universal purchase (see Table 3–7).

VFC Only

The VFC program provides federally purchased vaccine for all eligible children (Medicaid enrollees aged 18 and younger, uninsured children, Native American children) at participating public and private sites. Underinsured children may receive VFC vaccine at federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and rural clinics only. In 19 states, all children, including those not eligible for VFC, may receive state-supplied vaccines at public clinics. Section 317 and state revenues pay for the vaccines administered in public settings to children who do not qualify for VFC (information provided by CDC).

TABLE 3–7 Vaccine Supply Policy, January 2000

|

|

VFC Onlya |

Enhanced VFCb |

Universal Purchasec |

|

|

Alabama |

Arizona |

Alaska |

|

|

Arkansas |

District of Columbia |

Connecticut |

|

|

California |

Florida |

Idaho |

|

|

Colorado |

Georgia |

Maine |

|

|

Delaware |

Hawaii |

Massachusetts |

|

|

Indiana |

Illinois |

Nevada |

|

|

Iowa |

Maryland |

New Hampshire |

|

|

Kansas |

Michigan |

New Mexico |

|

|

Kentucky |

Minnesota |

North Carolina |

|

|

Louisiana |

Mississippi |

North Dakota |

|

|

Missouri |

Montana |

Rhode Island |

|

|

New Jerseyd |

Nebraska |

South Dakota |

|

|

Ohio |

New York |

Vermont |

|

|

Oregon |

Oklahoma |

Washington |

|

|

Pennsylvania |

South Carolina |

Wyoming |

|

|

Tennessee |

Texas |

|

|

|

Virginia |

Utah |

|

|

|

West Virginia |

||

|

|

Wisconsin |

||

|

Total |

19 |

17 |

15 |

|

aThese states provide publicly purchased vaccine to private health care providers only for Vaccines for Children eligibles. bThese states provide publicly purchased vaccine to all health care providers for both the Vaccines for Children and underinsured populations. “Underinsured” is defined as those who have health insurance that does not include immunizations as a covered benefit. cA universal purchase state offers all vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices to all health care providers to serve all patients, including those who are fully insured. dThe Vaccines for Children program was implemented in the private sector on January 1, 1999. SOURCE: CDC,1998c. |

|||

Enhanced VFC

States with enhanced VFC programs are like those described above, but in addition, state-supplied vaccines are made available to participating private providers for administration to underinsured children, comparable to the VFC policy for underinsured children served in FQHCs. In this case, Section 317 funds vaccines for non-VFC-eligible children served in public settings, and state revenues fund vaccines for underinsured children seen in the private sector. Sixteen states and the District of Columbia have enhanced VFC programs (information provided by CDC).

Universal Purchase

Universal purchase states supply vaccine for all children in the state, regardless of whether administration takes place in public clinics or participating private provider sites. VFC thus becomes one source of funding within a vaccine purchasing system for which all children are eligible, regardless of their insurance status. The 15 states with universal purchase programs, all of which were in existence prior to VFC, commit the highest level of state resources to vaccine purchase and to immunization programs overall (information provided by CDC), although not all universal purchase states buy all recommended vaccines.

ISSUES IN VACCINE PURCHASE

Generally, the introduction of VFC resulted in savings to states, as funding for the purchase of vaccines for most Medicaid-enrolled children could be shifted from the state to the federal level. The extent of those savings depended on several variables, include the following:

-

the extent of Medicaid enrollment,

-

the prices Medicaid paid for vaccines prior to VFC, and

-

whether states required Medicaid providers to enroll in VFC or discontinued reimbursing providers for privately purchased vaccine.

The way states used these Medicaid savings was highly variable. In response to the 1999 IOM state survey, 25 states said that Medicaid payment levels for vaccine administration or other pediatric care had increased, but only 4 states identified those increases as being related to savings from VFC (in one state, for example, the vaccine administration fee increased because the state Medicaid agency misinterpreted HCFA’s maximum allowable reimbursement as the minimum). Three states said these savings were used in other ways, such as increasing support for local health departments or purchasing vaccine for groups not covered by VFC. In most states, however, VFC-related savings did not accrue directly to the immunization program.

With Section 317 funds becoming increasingly limited, some states have restricted the availability of vaccine in public clinics. For example, for non-VFC-eligible children, a vaccine may not be available or may be restricted to certain age groups. In some states, public clinics are now required to check insurance status and refer children back to their private provider if they are not VFC- or 317-eligible. Though many states still adhere to the policy that free vaccines are available in the public sector to all children, practices in several urban areas suggest that some states have

qualified their distribution of free vaccines by placing greater emphasis on eligibility criteria. States that have tightened their screening and referral procedures have encountered some resistance from local health departments.

The intent of VFC was to eliminate a two-tiered system of care, in which poor children were precluded by cost from receiving immunizations in their medical homes. Yet a growing rift between VCF-eligible and -ineligible children has developed in many states. Recent additions to the primary immunization schedule—varicella, hepatitis A, the now rescinded rotavirus, and the new pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for infants—are relatively expensive vaccines. The recommended switch from OPV to inactivated polio vaccine also carries increased costs. Many states have faced difficult decisions regarding vaccine purchase for non-VFC children:

Issuance of new or expanded ACIP recommendations is one of our biggest problems. Every time a vaccine is added as an entitlement on VFC, we have to make sure that we don’t end up with different classes of children with different levels of protection; that means trying to come up with funding for that new vaccine for non-VFC children. The new recommendation doesn’t necessarily come along with extra 317 funds, and it doesn’t come with infrastructure funds that are needed to deliver the new vaccine and keep the records. It’s a constant juggling act to fund vaccines (Freed et al., 1999).

The problem is most pronounced for universal purchase states:

When the ACIP makes a recommendation for a new vaccine and they include it in the VFC program, then they are in effect pushing and controlling state budgets for universal purchase states. They do not take into consideration some very specific situations that exist for states. If our state was to lose universal status, it would have a very negative impact. We don’t have a lot of managed care, and most fee-for-service insurance does not cover immunizations. In many ways, we’re stuck between a rock and a hard place: even though universal status is costing more, it would be a real detriment to lose it.…

We have local health departments that are reluctant to provide the vaccine to VFC kids if they can’t do it for everybody. Our philosophy has been to push for the VFC kids to get vaccinated, because very often they are at higher risk for disease complications. We tell local health departments that they are able to vaccinate half the kids and they should do it. That doesn’t necessarily translate into universal acceptance of this policy at the local level (Freed et al., 1999).

The significant cost of immunizations may create point-of-service barriers to immunizations among both uninsured and underinsured children

and adults. In the case of uninsured children and a small number of underinsured children, federal policy provides a guarantee of coverage under the VFC program for ACIP-recommended immunizations, once a federal vaccine purchase contract has been completed. In addition, as noted earlier, 15 states have established universal purchase programs that provide access to free vaccine regardless of insurance coverage; however, these programs are limited to children.

Finding 3–5. Complex eligibility criteria and coverage conditions for the multiple federal and state programs supporting vaccine purchase and delivery have left gaps and omissions in the financial coverage of immunizations for children and adults. States respond to these residual needs by continuing to provide free vaccines in public health clinics, financed by a combination of Section 317 funds and state revenues.

Finding 3–6. The broad mission and general standards of service associated with the Section 317 program result in some overlap with more tightly constructed federal programs (such as VFC and SCHIP), but the amount of overlap is not large, and it should be seen as complementary rather than duplicative. The overlap allows the states to bridge coverage gaps, respond to timely needs, and advance the national goal of preventing disease through immunization.

SUMMING UP

VFC and SCHIP provide federal support for the purchase of vaccines for increasing numbers of disadvantaged children. However, residual needs remain, causing states to continue to rely on Section 317 vaccine purchase grants to serve at-risk children and adults who are ineligible for other federally supported vaccines. The scope of these residual needs varies among the states, depending on Medicaid eligibility and private health plan participation in meeting the health needs of low-income families.

The following specific factors contribute to the scale of residual needs within each state:

-

The eligibility requirements for VFC are more restrictive than those for Section 317 funds. Underinsured families that cannot afford to pay for vaccines or the administration fees charged by private practitioners may be ineligible for VFC but still seek vaccines from a local public health clinic.

-

Families enrolled in Medicaid or SCHIP may encounter delays in service or other access barriers in seeking care from private providers and thus return to public clinics for timely immunizations. The latter encoun-

-

ters are especially important to meet school entry requirements for young children and to address the health needs of recent immigrants.

-

The appearance of new vaccines offering valuable and long-awaited protection from additional infectious diseases has caused states to draw on Section 317 funds during transitional periods. This situation occurred, for example, during the 11-month period after ACIP recommended the varicella vaccine and before a federal purchase contract was negotiated.

States vary in the way they respond to their residual needs. A few states rely solely on federal support, since all of the vaccines provided through their public health clinics are financed by Section 317. Others have used state revenues to purchase additional vaccines to meet their residual needs. States have broad discretion in determining whether to use state or federal funds to purchase vaccines, hire staff, or support contractual efforts. Some states use internal funds for personnel and thus rely more heavily on federal vaccine purchases; others draw on federal employees where possible to staff their immunization programs, and reserve their own funds for vaccine purchases and other programmatic needs.

State investments in immunization services appear to have increased during the 1990s, but these increases have not been at the same dramatic levels seen with the creation of VFC or the early growth in Section 317 budgets. States were more likely to extend their efforts through their investments in expanded Medicaid coverage, both by increasing vaccine administration fees and by broadening the base of clients served by Medicaid plans. Evidence is not available to indicate how the states invested in other types of immunization programs during this period.

ENDNOTES

|

1. |

Despite their cost-effectiveness, immunizations may be relatively costly at the point of service. Immunization costs vary greatly by vaccine. They reflect the cost of development and manufacturing, the competitive situation (i.e., if there are multiple suppliers of a vaccine, its price tends to be lower), the length of time a vaccine has been on the market, and the federal excise taxes that are levied on vaccines under the Childhood Vaccine Injury Act. The vaccine administration fee includes the actual injection, assessment of any possible risks or counterindications, disclosure of information to parents and individuals to ensure that immunizations are provided only following informed consent, and compliance with record-keeping and reporting requirements under state and federal law. |

|

2. |

Two of these studies, the Current Population Survey March Supplement, conducted annually by the Census Bureau, and the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), conducted in 1996 by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (now the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality), are the basis for estimates of general insurance coverage used in this report. |

|

3. |

ERISA (29 U.S.C. §1000 et seq.) was enacted to regulate employer-sponsored pensions. The law contains a so-called “preemption” provision that exempts employer plans from most state laws. State laws that “regulate insurance” are saved; thus, employers that purchase insurance remain subject to state law under the holding in Metropolitan Life. ERISA also specifies, however, that employee benefit plans may not be considered insurance (29 U.S.C. §1144). In trying to make sense of this provision, the Supreme Court drew a distinction between employers that buy insurance and those that self-insure under their own ERISA plans. These self-insured plans are immune from the provisions of state law. |

|

4. |

These were ERISA amendments enacted as part of the same legislation that created the VFC program in 1993 (29 U.S.C. §1169 (d)). |

|

5. |

The original House VFC proposal would have covered all children uninsured for immunizations (that is, it would have reached underinsured children as well). The final legislation omitted all but a small percentage of underinsured children. The ERISA maintenance-of-effort provision was part of the House bill and was determined to be necessary to protect insured children from employer rollbacks in coverage in the face of the new program. Despite the fact that coverage of underinsured children was dropped in conference, the ERISA amendments survived. |

|

6. |

This estimate is based on the the KPMG survey’s estimate of the proportion of employees with each type of plan coverage (conventional, health maintenance organization [HMO], preferred provider organization [PPO], point of service [POS]), multiplied by the likelihood that each of those types of plans covers childhood immunizations, as shown in Table 3–2. Information from the 1998 Current Population Survey (Table 3–1) provides an estimate of the total number of children with employer-based coverage. |

|

7. |

Three of five reported coverage of poliovirus vaccine, inactivated (IPV); two of five reported coverage of rubella; four of five reported coverage of tetanus; one of five reported coverage of influenza; one of five reported coverage of pneumococcal vaccine; and two of five reported coverage of diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis (DTaP). |

|

8. |

The initial EPSDT statute did not specify particular services. |

|

9. |

Public Law 101–239, §6403(a), adding §1905(r) to the Social Security Act. Section 1905(r), 42 U.S.C. §1396d(r), sets forth all mandatory EPSDT services, including immunizations. |

|

10. |

Public Law 103–66, §13621(b), adding §1928 of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. §1396s. The VFC program was originally proposed as the initial phase of the Clinton Administration’s national health care reform proposal; this is reflected in another provision of the law, which would terminate the VFC program at the point at which federal law provides for immunization services for all children as part of a “broad-based reform of the national health care system” (§1928(g) of the Social Security Act; 42 U.S.C. §1396s(g)). |

|

11. |

§1928(h) of the Social Security Act; 42 U.S.C. §1396s(h). Children aged 19 to 21 are thus entitled to vaccines as part of the EPSDT program, but their vaccines are not covered through the VFC program. States remain responsible for immunization services for this age cohort, with federal contributions available at normal federal medical assistance percentage rates. |

|

12. |

This provision is found at §1903(i)(14) of the Social Security Act; 42 U.S. C. §1396(b). |

|

13. |

§1928(b)(3) of the Social Security Act; 42 U.S.C. §1396s(b)(3). |

|

14. |

§1928(f) of the Social Security Act; 42 U.S.C. §1396s(f). |

|

15. |

These are children under age 18 whose family income exceeds the Medicaid income level for children but does not exceed 50 percentage points above the Medicaid eligibility level (§2110(b)(1)(A) of the Social Security Act; 42 U.S.C. §1397jj(b)(1)(A)). |

|

16. |

§2104 of the Social Security Act; 42 U.S.C. §1397dd. |

|

17. |

§2103(c)(1)(D) of the Social Security Act; 42 U.S.C. §1397cc(c)(1)(D). Federal SCHIP guidelines require all SCHIP programs to cover immunizations in accordance with ACIP |

|

|

requirements (letter from Sally Richardson to State Medicaid Directors dated May 11, 1998, <http://www.hcfa.gov>). SCHIP-enrolled children in freestanding programs are considered insured and thus are ineligible for VFC vaccines. |

|

18. |

Based on MEPS estimates of eligible but not enrolled children for Medicaid and SCHIP (Selden et al., 1999). |

|

19. |

Based on 1998 Current Population Survey estimates of the number of persons under 18 who are uninsured (11 million) and MEPS estimates of those eligible for Medicaid and SCHIP but not enrolled (Selden et al., 1998; Selden et al., 1999). |

|

20. |

States that administer mandatory managed care programs under either §§1115 or 1915(b) of the Social Security Act can offer additional benefits to managed care enrollees. |

|

21. |

Medicare outpatient benefits, including immunizations, are provided under Part B of the program. Medicare Part A covers hospital and nursing home care. |

|

22. |

For example, anti-rabies treatment, tetanus antitoxin or booster vaccine, botulin antitoxin, antivenin sera, or immune globulin. |

|

23. |

There is a single national Medicare relative value scale (RVS) code, or payment weight, for vaccine administration. Like other physician services included in the RVS-based Part B payment system, the actual payment amount for vaccine administration varies according to a Geographic Practice Cost Index that distinguishes 360 localities nationally according to their relative medical practice input prices. These fees are also updated annually for general inflation. |

|

24. |

See also www.hcfa.gov/stats/mmcc0200.txt. |