2

Value of Food, Fiber, and Natural-Resources Research

Many studies have demonstrated the value of publicly supported research in science and technology. For example, the 1995 National Research Council report Allocating Funds for Science and Technology found that “the federal investments in [the US scientific and technical enterprise] have produced enormous benefits for the nation’s economy, national defense, health, and social well-being” (NRC, 1995, p. 3). A report of the US Committee for Economic Development, America’s Basic Research: Prosperity through Discovery, noted that “continued excellence in basic research is essential to America’s prosperity and global leadership” (CED, 1998, p. 2). That committee observed further that the federal government had long been the most important source of funding of basic research; this is true especially for food and fiber research, which until World War II was the principal beneficiary of federal funding.

Congress also has reviewed national trends in research, as recently described in the 1998 House Committee on Science report, Unlocking Our Future: Toward a New National Science Policy (the “Ehlers report”). The report, written under the leadership of physicist and US Representative Vernon Ehlers, documents the importance and the “stunning payoffs” of the federal research investment in the US technology enterprise. The importance of applications of research findings in the physical and chemical sciences and engineering to telecommunication, defense, transportation, and health is duplicated in the importance of applications of research in biology, agriculture,

and engineering to food, fiber, and natural resources—the focus of this report. Agricultural and physical sciences alike benefit immensely from understanding-driven or basic research, targeted basic research, and mission-directed or applied research (the terms used in the Ehlers report).

In general, 20th century research in food, fiber, and natural resources has contributed substantially—in both quantitative and qualitative terms—to the stability and prosperity of the US economy and to the broader world economy. In this chapter, the committee summarizes the economic value of this research to the US economy, discusses the impact of advances in life sciences, and provides an overview of trends in public and private-sector funding of food, fiber, and natural-resources research.

ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTIONS

The economic contributions of food, fiber, and natural-resources research are reflected in the contributions made by the food and fiber system to the growth of the US and global economies (Lipton et al., 1968; Daily et al., 1998). In 1996, US farming and its related industries accounted for $997.7 billion—13% of the gross domestic product—and employed almost 23 million people and 16.9% of the civilian workforce and 20% of the workforce residing in nonmetropolitan areas. Farming itself accounts for less than 1% of the gross domestic product and employs only about 1% of the US workforce, but it is just one link in the value-adding chain of input suppliers, capital providers, processors, transporters, service units, retailers, and others who produce and deliver food and fiber products to consumers.

The United States is the world’s leading exporter of food and fiber products, with sales of $60.4 billion in 1996. Crops from more than 30% of US farmers’ acreage are exported. USDA’s Economic Research Service estimates that each dollar earned from exported food and fiber stimulates another $1.32 of output in the United States. US food and fiber exports alone were estimated to support about 859,000 full-time jobs in 1996.

Food and fiber exports also are important in narrowing the foreign-trade gap. In 1996, the food and fiber trade surplus was $26.8 billion; the non-food-and-fiber account was in deficit by $235.1 billion. The surplus adds to the strength of the US dollar, which helps to control inflation and moderates the prices of imported goods. The nature of food and fiber exports has changed substantially from mostly bulk commodities—such as grain, feed crops, and oil crops in the 1960s and 1970s—to mostly high-value items, such as meat products, fruits, vegetables, and beer and wine. In addition to exports, 1995 sales by foreign food-manufacturing affiliates of US companies totaled another $113 billion.

The high efficiency of production and delivery of US food and fiber enables Americans to spend only about 11% of their disposable income on food—the lowest rate of expenditure in the world. In contrast, estimated rates of disposable income spent on food are 17% in Europe, 30% in South America, and 51% in India (B.Meade, USDA, personal communication, March 23,

1999). The low cost of food frees consumer income for other uses, allows a cost-effective focus on food quality and safety and human nutrition, and cuts costs to US taxpayers for food stamps and related public-assistance programs.

The US food and fiber system has responded quickly and effectively to important long-term trends. Changing incomes, demographics, lifestyles, and consumer perceptions of relationships between health and diet are among those trends. The ethnic diversity of the US population has broadened the array of food products available to consumers. The need for convenience in food-purchasing choices has led to greater diversity of services in basic foods (processing and prepared food). Fast-food establishments, restaurants, and hotel dining have shifted the location and style of consumption. Concerns about safety and dietary issues have led to products that have improved health and safety attributes, including improved nutritional quality. Health and safety information is now transmitted in a more coordinated fashion through the stages of the food system because of increasing reliance on production contracts and vertical integration.

RATES OF RETURN FROM FOOD AND FIBER RESEARCH

Since the late 1950s, more than three dozen studies have estimated rates of return on public investment in food and fiber research in the United States (Fuglie et al., 1995; Alston and Pardey, 1996; Barry, 1997). The studies have, for the most part, found high real rates of return from most categories of applied and basic food and fiber research. The estimated returns on research typically range from 35% to 60% per year. Those rates are high relative to the government’s cost of funds, relative to returns on alternative investments, and relative to private sector rates of return. Fuglie et al. (1995) summarized the aggregate returns to agricultural research and extension for the period 1964 through 1982 (see table 2–1).

Table 2–1 shows that the annual rate of return on research investment in agriculture was estimated to be about 41% between 1950 and 1982. Such a historically high rate of return before 1982 illustrates the powerful impact of well-managed, targeted food and fiber research. Since the first commercial introduction of a recombinant-DNA product (human insulin) in 1982, there has been a substantial change in the technology of agriculture and in chemistry and biology. Maintaining such an effect of research and return on investment in food, fiber, and natural resources will require focused and wise investments in the research enterprise that will catalyze advances in agricultural biotechnology and in fundamental biologic and engineering research applied to food, fiber, and natural resources.

The return on investment in food and fiber research includes not only returns to the technology developers that benefit from the research outcomes, but also the returns to farmers, agribusinesses, consumers, and other members of society that benefit from the research outcomes. Thus, food and fiber research return rates have a broader scope and are generally larger than private rates of return on shorter-term industrial projects, which tend to be 10% to 15%.

TABLE 2–1 Aggregate Returns on Public Investments in Agricultural Research and Extension

|

Study |

Methodology |

Period |

Annual Rate Return, % |

|

Griliches, 1964 |

Production function |

1949–59 |

35–40 |

|

Latimer, 1964 |

Production function |

1949–59 |

—a |

|

Evenson, 1968 |

Production function |

1949–59 |

47 |

|

Cline, 1975 |

Production function |

1939–48 |

41–50 |

|

Huffman, 1976 |

Production function |

1964 |

110 |

|

Peterson and Fitzharris, 1977 |

Economic surplus |

1937–42 |

50 |

|

|

|

1947–52 |

51 |

|

|

|

1957–62 |

49 |

|

|

|

1967–72 |

34 |

|

Lu, Quance, and Liu, 1978 |

Production function, R&Eb |

1939–72 |

25 |

|

Knutson and Tweeten, 1979 |

Production function, R&E |

1949–58 |

39–47 |

|

|

|

1959–68 |

32–39 |

|

|

|

1969–72 |

28–35 |

|

Lu, Cline, and Quance, 1979 |

Production function, R&E |

1939–48 |

30.5 |

|

|

|

1949–58 |

27.5 |

|

|

|

1959–68 |

25.5 |

|

|

|

1969–72 |

23.5 |

|

Davis, 1979 |

Production function |

1949–59 |

66–100 |

|

|

|

1964–74 |

37 |

|

Evenson, 1979 |

Production function |

1868–1926 |

65 |

|

White and Havlicek, 1979 |

Production function |

1929–72 |

20 |

|

White, Havlicek, and Otto, 1979 |

Production function |

1929–41 |

54.7 |

|

|

|

1942–57 |

48.3 |

|

|

|

1958–77 |

41.7 |

|

Davis and Peterson, 1981 |

Production function |

1949–74 |

37–100 |

|

White and Havlicek, 1982 |

Production function, R&E |

1943–77 |

7–36 |

|

Lyu, White, and Lu, 1984 |

Production function |

1949–81 |

66 |

|

Braha and Tweeten, 1986 |

Production function |

1959–82 |

47 |

|

Huffman and Evenson, 1989 |

Production function |

1950–82 |

41 |

|

Yee, 1992 |

Production function |

1931–85 |

49–58 |

|

a Not significant. b R&E gives estimated rate of return on combined research and extension expenditures. Otherwise, estimate is for research alone. Source: Adapted from Fuglie et al. (1995). |

|||

The research returns reflect several other key characteristics. First, the research benefits generally occur over long periods (for example, up to 40 years). Second, specific research outcomes are relatively risky, especially when high payoffs are concentrated in a few major breakthroughs. Third, the research returns are magnified by stimulating technology adoption and further research in other countries, economic sectors, and industries.

The rates represent the returns on primarily production-based research involving plants and animals. The returns typically do not include the costs of

externalities attributed to research, such as possible environmental degradation, adjustment costs of displaced labor, and other adverse effects on human health, communities, and families. Also not included in these returns are the significant contributions of economics and other social science research, which provide additional value. Examples of social-science research outcomes are economic and social policy analyses, decision support and forecasting information, institutional innovations, and new organizational structures in food and fiber production and distribution.

IMPACTS OF ADVANCES IN LIFE SCIENCES

Largely within the last decade, food and fiber research investments by the private sector have increased from a historical level of 2% to 4% of gross sales to 10% or more—a level that is more typical of value-added products than of traditional agricultural commodities. The trend reflects the reality of today’s high research costs, largely the result of expensive technology not available 20 years ago. The development and application of biotechnology clearly illustrate this expense. Not only is the technology expensive, but its development often requires a multidisciplinary approach. For environmental technologies and others with no immediate proprietary application but widespread public payoffs in the long term, funding falls exclusively to the public sector. Moreover, the public sector is increasingly responsible for training the students that are needed by industry to use new technology. Assigning relative contributions of public and private funds in support of research is difficult.

The development of new technologies applicable to food and fiber has led to new relationships between the research and regulatory arms of the US Department of Agriculture and between USDA and other regulatory agencies. For example, genetically engineered plant and animal products now fall under the jurisdiction of the Food and Drug Administration if the engineering leads to substantially altered products. Products that contain new proteins, fats, or carbohydrates or that have greater potential for allergenicity than existing varieties must pass rigorous premarket review and must be appropriately labeled when brought to market.

Similarly, new technologies that affect how food and fiber production influences air, soil, and water quality are leading to new relationships between food and fiber research and the regulatory agencies responsible for environmental protection—in particular, the Environmental Protection Agency and its state-level equivalents. In some cases, such as high-density animal production, new technologies might increase the risk of environmental degradation; in other cases, such as precision agriculture, new technologies promise opportunities for improved environmental stewardship. All advances in technology place additional demands on the research enterprise apart from the discovery and development of the advances themselves.

PUBLIC-SECTOR AND PRIVATE-SECTOR RESEARCH FUNDING

The food, fiber, and natural-resources sciences held a privileged position until World War II. As late as 1940, almost 40% of federal expenditures for research and development ($29 million of $74.1 million) was allocated to USDA intramural and state experiment-station research (Mowery and Rosenberg, 1989). World War II transformed the federal research system. First, the government contracted large amounts of research to the private sector. That shifted much federally financed research, particularly defense-related research, to industry. Since World War II, about 75% of all federal R&D expenditures have gone to the private sector (Mowrey and Rosenberg, 1989). Second, the war spawned huge increases in federal R&D spending. National-security concerns were often the principal drivers. Social issues and priorities also motivated the expansion of federal R&D investment, including the Great Society programs, environmental concerns, public health, and recently concerns about the international competitiveness of US industries. Until the late 1970s, the United States spent more on research than all other industrialized countries combined (Mowery and Rosenberg, 1989).

After World War II, other federal agencies received a greater proportion of federal research funding relative to USDA. Because defense-related research dominated federal research spending, the Department of Defense, Department of Energy, and National Aeronautics and Space Administration have accounted for a large share of federal research obligations (about 70% in 1998). However, university-based research also received a large boost from the creation of the National Science Foundation (NSF) in 1950 and the expansion of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NSF and NIH greatly expanded federal support for university research and for the universities’ research infrastructure. In 1998, NSF and NIH together accounted for almost 22% of all federal research obligations and over two-thirds of the federal research obligations for universities and colleges (NSF, 1999). By 1998, USDA expenditures for research were about 2% of all federal research spending, and about 2% of federal support for university research was for food, fiber, and natural-resources research (NSF, 1999).

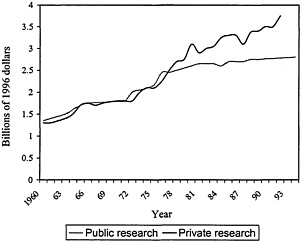

The government’s role in supporting food and fiber research has had to adapt to the rising involvement of the private sector in research and development. The post-World War II period has witnessed a large increase in the private sector’s contribution to food and fiber research. Several factors have spurred private industry’s interest in food and fiber research, including scientific advances in molecular biology, increased market opportunities, and stronger intellectual property rights to biologic inventions. Between 1960 and 1994, private sector food and fiber research expenditures more than tripled in real terms. Today, the private-sector invests more in food and fiber research than do the federal and state governments combined (figure 2–1).

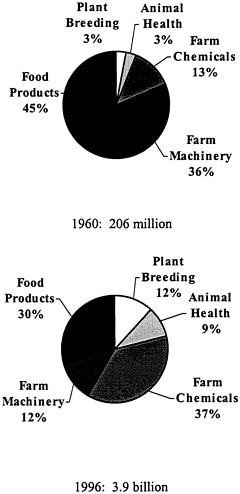

Those research expenditures mask a major shift in the type of research conducted in the private sector (figure 2–2). In 1960, the responsibilities of public and private research were clearly drawn. More than 80% of private research was for improving farm machinery or developing new food products or

processing methods, and public research concentrated on increasing yields of crops and livestock. Since then, the private sector has developed a large research capacity in subjects long dominated by the public sector, such as plant breeding. By 1996, nearly 21% of private research was devoted to increasing crop and livestock yields by supplying farmers with improved crop varieties, animal breeds, feeds, and pharmaceuticals. Those trends suggest continuing challenges of overlap between the public and private sectors in some kinds of food and fiber research.

The dramatic growth in private investment in food and fiber research might have overshadowed the nation’s historical public research agenda. The recent explosion of private investment in the food and fiber system is, however, built on the preceding long-term public effort. There is no reason to doubt that the importance of public-sector research to industry is any less for food and fiber than for other kinds of research. A 1997 patent-citation study—which found that 70% of patent-application citations were of public-sector research (Narin et al., 1997)—illustrates well the symbiotic linkage between public and private research investments. The public sector provides innovative and creative research that could take considerable time for commercial development or might not be undertaken at all.

FIGURE 2–1 Food, fiber, and natural-resources research expenditures in the United States, 1960–1996

Sources: Based on Klotz, Fuglie, and Pray (1995), US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Private-Sector Agricultural Research Expenditures in the United States; public research data derived from US Department of Agriculture Inventory of Agricultural Research