2

The U.S. Federal Helium Reserve and the Helium Privatization Act

This chapter examines (1) current federal and private helium facilities and capacities and (2) the details of the Helium Privatization Act of 1996. It is critical that the distinction between the Federal Helium Reserve and the Bush Dome reservoir is understood. The Federal Helium Reserve pertains solely to the crude helium gas that currently resides in the Bush Dome reservoir and includes neither the storage facility itself nor the associated pipeline.

FEDERAL AND PRIVATE HELIUM FACILITIES AND CAPACITIES

Table 2.1 summarizes the ownership and location of all domestic helium plants as of 1998.

Federal Helium Facilities

Federal helium facilities have been involved in the entire range of helium production processes, from the extraction of the natural gas from which helium derives to the production and storage of crude helium and to the purification, liquefaction, and final transportation of pure helium. The BLM extraction operations and purification and liquefaction facilities are all located in Masterson, Texas. These facilities are relatively old, however, and were frequently criticized before Congress as inefficient. In 1996, the last full year for which statistics are available, federal operations accounted for 220 million scf (6.07 million scm) of the 2.6 billion scf (71.9 million scm) of grade A helium that was domestically sold, or approximately 8.4 percent of the total U.S. market. The plants were mothballed in 1998, as stipulated in the Helium Privatization Act of 1996. No crude or pure helium has been produced or sold by the federal government since that time.

TABLE 2.1 Ownership and Location of Helium Extraction Plants in the United States in 1998

|

Category and Owner or Operator |

Location |

Product Purity |

|

Government-owned |

|

|

|

Bureau of Land Management |

Masterson, Tex. |

|

|

Private industry |

|

|

|

Air Products Helium, Inc. |

Hansford County, Tex. |

Grade A heliuma |

|

Air Products Helium, Inc. |

Liberal, Kans. |

Grade A heliuma |

|

Amoco |

Ulysses, Kans. |

Crude heliumc |

|

BOC Gases |

Otis, Okla. |

Grade A heliuma |

|

CIG Company |

Keyes, Okla. |

Grade A heliuma |

|

CIG Company |

Lakin, Kans. |

Crude helium |

|

Crescendo Resources |

Sunray, Tex. |

Crude helium |

|

ExxonMobil |

Shute Creek, Wyo. |

Grade A heliuma |

|

GPM |

Moore County, Tex. |

Crude helium |

|

GPM |

Hansford County, Tex. |

Crude helium |

|

KN Energy, Inc. |

Bushton, Kans. |

Crude helium |

|

KN Energy, Inc. |

Scott City, Kans. |

Crude heliumd |

|

National Helium Corp. |

Liberal, Kans |

Crude helium |

|

Nitrotec |

Chillicothe, Tex. |

Grade A heliume |

|

Nitrotec |

Cheyenne Wells, Colo. |

Grade A helium |

|

Pioneer Resources |

Fain, Tex. |

Crude helium |

|

Pioneer Resources |

Satanta, Kans. |

Crude helium |

|

Praxair, Inc. |

Bushton, Kans. |

Grade A heliuma |

|

Praxair, Inc. |

Ulysses, Kans. |

Grade A heliuma |

|

Trident NGL |

Ulysses, Kans. |

Crude heliumf |

|

Unocal |

Moab, Utah |

Grade A heliuma |

|

Union Pacific Resources |

Cheyenne County, Colo. |

|

|

Williams Field Services |

Baker, Okla. |

Crude helium |

|

a Including liquefaction. b Stopped production in April 1998. c Began production in May 1998. d Output is piped to Ulysses, Kansas, for purification. e Began production in December 1998 (est.). f Stopped production in May 1998. g Began production in October 1998. |

||

Of greater consequence for this study are the specifications of the Federal Helium Reserve. The Federal Helium Reserve is stored in the Bush Dome reservoir in the Cliffside gas field near Amarillo, Texas (Figure 2.1). The Bush Dome reservoir originally contained one of the early helium-rich natural gas deposits discussed in Chapter 1 . The formation is approximately 3,500 ft (1,100 m) deep and about 300 ft (91 m) thick and has a 10 percent porosity. The government owns approximately 50,900 acres (20,200 ha) in the Bush Dome region. The Dome has a total capacity of approximately 45 billion scf (1.2 billion scm). The facility currently contains approximately 30.5 billion scf (850 million scm) of government-owned crude helium, or about a 10-year world supply at the current rate of use. Private industry stores an additional 4 billion scf (110 million scm) of helium in the reservoir.

FIGURE 2.1 The storage facility at Cliffside gas field (courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management).

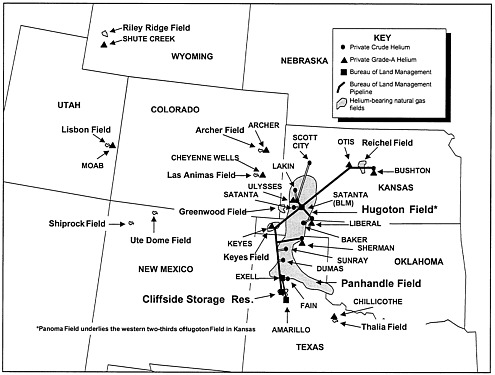

In addition to the reservoir, the facility possesses roughly 450 mi (720 km) of pipeline and associated hardware. The pipeline stretches through Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas and connects 17 private crude helium production and refining plants to the federal reservoir (Figure 2.2). Many of these plants are extracting gas from the Hugoton gas field. The operating companies regularly deposit and extract their own supplies of crude helium to and from the reserve for either storage or final purification and sale, respectively. They are assessed fixed charges for contract administration and connections to the government pipeline. In addition, a company pays variable charges based on its crude helium activity.

It is important to stress three things about the Bush Dome reservoir. First, it is a unique facility. The long-term storage of crude helium would be very difficult without such a facility, and the long-term storage of both gaseous and liquefied refined helium is currently not feasible. The Bush Dome reservoir could be adapted for the storage of crude helium because of its recognized ability to contain natural gas with relatively high helium concentrations (about 1.86 percent). There is no comparable storage facility for helium anywhere else in the world. This is important, because other storage facilities will be required as the Hugoton gas field is drawn down and other fields become the primary sources of helium.

Second, as crude helium is injected into the Bush Dome reservoir, there is some mixing with the remaining native natural gas. As the crude helium inventory is reduced, the helium content can be expected to deteriorate toward the end of the life of the reserve. Thus, it may not be possible to recover all of the crude helium currently in storage without installing upgrading facilities at some time in the future. A facility for upgrading diluted crude helium as it's removed from storage could conceivably also be used to recover helium from the native gas in the reservoir.

Third, the rates for the fixed and variable charges assessed private industry for the storage of helium at the Cliffside facility are calculated to offset the operating expenses of the facility. Each company that currently stores helium in the Federal Helium Reserve has signed a helium storage contract between itself and BLM. The contract includes a cost-recovery formula that allocates the budgeted costs for the storage program to all the storers in the system. The fixed costs are $12,000 for each storage contract and $20,000 for each company connection to the crude helium pipeline. These charges reflect the approximate cost associated with these functions (i.e., contract administration and maintenance of the custody transfer point). The variable costs are based on the company's share of the activity on the storage system in the preceding year. For example, a company's total helium acceptances, redeliveries, and average helium storage are added up and compared to the total for all companies having storage contracts. This share is then applied to the remaining costs of the helium storage program (budgeted minus fixed costs). The company is billed for its fixed costs at the start of the fiscal year and its portion of the variable costs in nine monthly installments starting in January and for the remainder of the fiscal year. By the terms of the contract, all costs budgeted for a given year are collected using this formula. The moneys collected have been in the $2 million range over the last couple of years. This contractual cost-recovery system was developed by BLM personnel in 1995, with the final language having been negotiated in a series of meetings with the private storers. The cost-recovery contractual system is thus divorced from any assessment of the economic value of the storage service and could be inhibiting the amount of income generated by the facility.

Private Helium Facilities

Fourteen private companies owned a total of 20 plants in 1996. Of these plants, 13 engaged in helium extraction and 11 (with some duplications) in purification, and 8 also liquefied helium. The domestic crude helium industry can be considered to consist of three basic elements. The first element includes the private producers in the Hugoton-Panhandle complex, which are already utilizing the helium pipeline and Bush Dome reservoir. The second element includes private producers in the Rocky Mountain region, none of which are tributary to the helium pipeline network and so cannot use the Cliffside storage facility. The third element is the Federal Helium Reserve itself.

The private refiners in the Hugoton-Panhandle complex (i.e., the first element) rely on the Cliffside facility to act as a flywheel. Natural gas extraction companies generally sell crude helium to helium refiners on the basis of long-term (e.g., 20-year), take-or-pay contracts. These contracts require that refiners purchase certain quantities of helium every year, whether they take it or let it be vented. Since it is a waste of capital to let the crude helium be vented, the refiners with access to the pipeline store all of their crude helium in the Cliffside facility and remove and

FIGURE 2.2 Major helium-bearing natural gas fields in the United States (courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management).

refine it as needed. Any crude helium in excess of current market demand will thus remain in the Cliffside facility and become part of the company's private stockpile. The amount of helium produced from the Hugoton-Panhandle complex would certainly be less if the Cliffside facility were not available.

The existence of the Federal Helium Reserve itself (i.e., the third element) would appear to have little effect on industry as long as it is held in storage. Sale of federal crude helium assumes that the customers who buy it can purify and market the product (unless, of course, these customers choose to simply leave their purchases underground at Cliffside). The only reason for nonproducing customers to buy from the reserve would be for speculation, holding onto it and waiting for the time when the Hugoton-Panhandle field's helium was exhausted. The crude helium in the Bush Dome reservoir could then be sold—at a profit—to the refiners along the pipeline to extend their production lifetime. However, the likelihood of this occurring is completely dependent on the price at which the crude helium can be bought initially.

The information presented in Table 2.1 and Figure 2.2 suggests that significant private helium production is coming from the second element, which is gas fields that do not enjoy access to the helium pipeline. The Rocky Mountain producers (the most important one by far is ExxonMobil) could continue to operate even if Hugoton production was to decline.

Overall, as will be discussed in Chapter 5, the domestic industry appears to be stable and contributes to realistic conservation, especially by using the Bush Dome reservoir as a flywheel. It is not unreasonable to believe that proximity to the Cliffside facility and the size of the helium-bearing natural gas reserves (to be discussed in Chapter 4) will weight heavily in the overall assessment of helium privatization and the impacts it may have.

HELIUM PRIVATIZATION ACT OF 1996

The Helium Privatization Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-273) was signed by President Clinton on October 9, 1996. The act basically mandated that BLM (1) terminate its production and sale of Grade A helium (i.e., 99.995 percent helium or better) by April 9, 1998, which has been done; (2) dispose of all helium production, refining, and sales-related assets within 24 months of closure of the BLM helium refining plant, which has not yet been accomplished, and (3) sell all of the Federal Helium Reserve of crude helium in excess of 0.6 billion scf (17 million scm), which is awaiting the publication of this report and the consequent actions of the secretary of the Interior.

The legislation directs the secretary of the Interior to commence offering for sale, on a straight-line basis, approximately 30.5 billion scf (850 million scm) of the Federal Helium Reserve at any time before January 1, 2005, and to complete offering it for sale not later than January 1, 2015. Furthermore, the act determines a price by dividing the helium program's total debt (about $1.4 billion) by the volume of crude helium in storage. According to the Congressional Research Service, this would establish a selling price of approximately $43 per thousand scf ($1.50 per scm), which is roughly 25 percent higher than the current commercial price of crude helium. The act goes on to use this price as the basis for minimum acceptable bids. Potential problems stem from the pace and price of sales that the act contemplates. The Congressional Research Service points out that straight-line sales of the stored helium, even if begun in 1997, would amount to about 20 percent of current annual consumption. If the sales did not begin until 2005, such sales would amount to more than 40 percent of current domestic consumption. The meaning of the term ''straight-line sales" is also not clear. Would, for example, unsold helium from the first year's offer for sale have to be added to the second year's offer? If this were to happen, BLM might find itself near the end of the 10-year sale period with most of its crude helium still on hand. In short, P.L. 104-273's setting of rigid prices and sales volumes could work against the sale of the reserve, or it could attract potential buyers convinced that the asking price must eventually rise.

Some of the crude helium currently residing in the Federal Helium Reserve is already being sold. The legislation stipulates that all pure helium bought by government agencies must derive from government-owned crude helium. Since BLM's refining facilities are being surplused in response to the Helium Privatization Act of 1996, BLM is required to sell the crude helium to private refiners, which then purify the material for sale to the government agencies. The price used for the crude helium is the higher one stipulated by the legislation, which means that government agencies are paying more than the price of commercially available pure helium. Because there is a net storage of privately owned helium, the effect of these transactions is the sale of a portion of the federal reserve to private industry.

As stated at the beginning of this chapter, the legislation requires the government to continue to operate the Cliffside gas field storage system, including the storage field itself and the

pipelines needed to store and handle both government and private crude helium. As currently required, the government will continue to collect royalties and sales fees for helium taken from federal lands. The cost of these ongoing activities will be defrayed by allowing the government operator (either BLM or a contractor) to use revenue from helium or other product sales, together with sales of excess property (e.g., helium transportation containers, compressors, and land), to establish a helium production fund. Interestingly, helium-related research money can also be taken from the fund. In the long run, however, the act assumes that all amounts in excess of operational needs will go to the Treasury, first to pay back the indebtedness of the helium program and eventually to the General Fund. The act envisions that after the disposals have been completed, the budget for helium operations will be $2.0 million or less per fiscal year.

The legislation contains a number of specific exceptions not uncommon in privatizations. For example, "the sales shall be at such times during each year and in such lots as the secretary determines, in consultation with the helium industry, to be necessary to carry out this subsection with minimum market disruption." In another instance, the act recognizes that once federal production of grade A helium ceases, federal customers will have to turn to private suppliers. While the implication is that prices might fall somewhat, there is no way to be certain until the market is fully stabilized.

P.L. 104-273 provides considerable additional detail about the liquidation of the Federal Helium Reserve that probably reflects the many concerns that were presented to the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources in 1996, as well as to various other committees and panels throughout the 1990s. Other attempts to reform or eliminate the Federal Helium Reserve had fallen short or failed, and interest groups on all sides were alerted, if not alarmed, by the prospective sale of the Federal Helium Reserve. One result of this concern was the addition of Section 8, which was added to the House version by the Senate committee with a "do pass" recommendation. As stated in the Preface to this report, Section 8 (see Appendix B) of the legislation mandated that the NRC conduct a study and produce a report that assesses whether disposal of the Federal Helium Reserve "will have a substantial adverse effect on U.S. scientific, technical, biomedical, or national security interests." It should be noted that economic interests are not mentioned and that, after the NRC report is transmitted to the secretary of the Interior, the secretary is required to consult with the U.S. helium industry and the heads of any federal agencies deemed to be affected by the legislation. In the event of a determination of ''substantial adverse effect," the secretary would be free to make recommendations, including proposing remedial legislation to Congress, that would mitigate the adverse effect.

Although scientific, technical, and security concerns are prominent in the act, and especially in Section 8, it is clear that production and marketing factors will be important in determining if privatization can serve national needs and avoid "adverse effects," since the only assets subject to disposal are the federal crude helium in storage and the extraction, refining, and sales-related assets that produced BLM's grade A helium. To accurately assess the impact of the sale of the Federal Helium Reserve requires a knowledge of helium's uses (Chapter 3), its present and future supply (Chapter 4), and its market economics (Chapter 5).