2

Is the VA National Formulary Overly Restrictive and Does It Prevent Physicians from Meeting the Health Care Needs of Veterans?

To begin, the committee concluded that the answer to the question posed by Congress and the VA—whether the VA National Formulary was overly restrictive—was dependent, at least in part, on judgment. The restricted budgetary resources of the VHA that make veterans ' health care a zero-sum game in which inflation in one sector obligates deflation in another will, of necessity, influence such a judgment. The IOM committee, as a panel of experts with broad experience, identified and evaluated the various elements, dimensions, or categories of restrictiveness as they are employed by the National Formulary and formulary system and compared them in pharmacy benefits of the VA, private-sector MCOs and PBMs, and two public programs, Medicaid and the Department of Defense. The information in Chapter 3 of this report supports an analysis of the economic factors that underlie some decisions on restriction. The central elements of restrictiveness of the formulary are also susceptible to independent analysis. Although there are deficiencies in the data, the committee found, in many instances, that there was sufficient information to support discussions, analyses and conclusions reached in this chapter.

BACKGROUND

Restrictiveness is a multifactorial attribute of a formulary and formulary system. At its root, the restrictiveness of the VA National Formulary, including the local, VISN, and national lists and systems, and the nonformulary exceptions processes, is a measure of the stringency of the controls on veterans' access to prescribed medicines at the appropriate times. Comparisons with other systems

can influence judgments about such controls. Nevertheless, if formulary structure or formulary system controls deny or significantly delay access to drugs that, in the reasonable judgment of medical experts, are clinically indicated, then the VA National Formulary meets a definition of “overly” restrictive.

Such clinically indicated or medically necessary medicines are not necessarily those identified in television commercials or by pharmaceutical sales representatives, or those preferred by patients or physicians for other reasons. VA National Formulary treatment guidelines and drug class reviews are intended to improve prescribing decisions by caregivers. The evidence that there is room for such improvement is substantial. Physicians are often swayed by industry commercial messages when scientific data would indicate otherwise (Avorn et al., 1982; Avorn and Sounerai, 1983). Prescribers respond to patient pressure that may result from direct-to-consumer advertising (Barents LLC, 1999). Physicians also may provide drugs primarily for a placebo effect or to meet patient expectations for some sort of intervention (Schwartz et al., 1989). Prescribing errors are distressingly frequent throughout the U.S. health care system and have been shown in demonstrations to be correctable through consultation with clinical pharmacists or reengineering of systems of health care (Institute of Medicine, 1999; Leape et al., 1991, 1995, 1999).

Elements of Restrictiveness

The committee decided that the question of restrictiveness could be approached by examining several characteristics of the National Formulary and formulary system, both on their own merits and in comparison with other formulary systems. The elements of restrictiveness discussed in this chapter include the following: formulary size and coverage of agents in different therapeutic classes; timeliness of addition of new drugs or drug products and reappraisal of formulary listings; and appropriateness and responsiveness of the nonformulary exceptions process and access to nonformulary drugs. Restrictiveness also depends on therapeutic interchange policies and practices that are standardized and protect at-risk groups of patients from drug treatment misadventures. Coverage of nonprescription (over-the-counter [OTC]) drugs and generic substitution are also important. The committee concluded that the key elements in the VA National Formulary are the number of classes closed, number of drugs in closed classes, responsiveness of the nonformulary process, and sensitivity of the therapeutic interchange policy and

|

Elements of Restrictiveness

|

procedure to patient risks and prescriber prerogatives. These are central elements in the implementation and management of the National Formulary, and revision of policies and procedures governing them will represent significant changes.

Criteria that the committee used for judging the restrictiveness of the attributes of the VA National Formulary include the following: how they compare to those of other organized private and public health care systems; how they compare to reasonableness standards in the literature or in the informed judgment of the committee; how they compare to objective standards where these are available; and how they affect the satisfaction and opinions of patients and prescribing physicians. The committee identified the elements of restrictiveness in the VA National Formulary and formulary system and, for comparison, in private-sector formularies and formulary systems. These are presented in Table 2.1. Private-sector data were collected through a special questionnaire (see Appendix B) circulated in January 2000 by the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) to six major private-sector PBMs and two small MCOs covering in total about 176 million lives. Care should be exercised in interpreting these data in the sense that covered lives may be overstated due to double counting of two-wage-earner families. Also, some PBMs that provide claims services and not formulary management may have reported their own policies and not the actual client MCO formulary policies. Public-sector (Medicaid) elements are identified and discussed in Chapter 5 and summarized in Table 5.1 of that chapter. In all of these comparisons, clear differences in the involved health care systems in which the formularies are embedded suggest caution in drawing inferences, although the committee has attempted to limit the comparisons to the formularies and formulary systems not the health care systems.

Restrictiveness can be approached in another way. The use of restrictiveness elements or the characteristics of formularies and formulary systems that affect the availability of, or ease of obtaining, a drug in a health care system can be categorized, with the more severe limitations being those that absolutely deny access or limit access without medical need-based exceptions. Controls without need-based exceptions, such as absolute limits on numbers of prescriptions in some Medicaid programs, are rare in the private sector and are not part of the VA National Formulary. Box 2.1 lists such formulary limitations on receiving a safe, effective, and medically necessary drug, some with essentially no limit on access, others with complete inaccessibility. The committee concluded that the most important limits incorporated into restrictive designs were exclusions, volume or quantity limits that were unresponsive to medical necessity, drugs not being listed in a closed class, or not included or covered in the formulary, high copayments (these are also not related to medical necessity), and administratively and medically strict prior approval or nonformulary exceptions processes. Although this chapter is not organized by the listing in Box 2.1, an appreciation of these factors— their roles in, and contributions to, the availability or restriction of choice of drugs and drug products, is an important background to the committee's exploration of elements of restrictiveness of the VA National Formulary and comparison formularies. Formularies usually fall into one or more of the listed limitation categories and

implement them to varying degrees. The first step in analyzing restrictiveness is understanding these elements. The next is knowing how they contribute variably to different formulary designs that affect the availability of drugs.

SIZE AND COVERAGE OF THE NATIONAL FORMULARY

The VA National Formulary, dated July 1999, lists about 1,200 items, of which 133 are medical-surgical supplies. The nonsupply items are distributed in 254 classes and subclasses. Some of these classes are vitamins, dentals, vaccines, diagnostics, radiographic contrast agents, and intravenous (IV) or other solutions, that is, items that would not be considered typical pharmaceuticals and are often not included in other formularies. About 15 of the listings indicate that a drug class is under review without referring to any specific agent. Drugs needed in these classes will be found in VISN and local formularies until reviews are completed and national decisions made. About 170 of the items listed are OTC, such as nutritional supplements, vitamins, cough and cold remedies, simple ointments and other topicals, eye and nose drops, antacids and laxatives, and the like. Items such as these may be substituted for more expensive or risky prescription drugs. About half of the items in the VA classes are not separate chemical agents, but represent the same chemical entity in injectable, oral, or topical form. Dosage strengths are generally not identified. Drug dosages that are stocked and immediately available in VHA health care facilities are left to the discretion of each facility's management.

TABLE 2.1 Comparison of VA and Private Health Care

|

VA (%) |

Private Health Care (% of 176 million lives) |

|

|

P&T committee composition |

||

|

Pharmacists |

52a |

32 |

|

Physicians |

44 |

63 |

|

Others |

4 |

5 |

|

Excluded |

||

|

DESI |

100 |

10 |

|

Experimental |

100b |

99 |

|

Off-label use |

0 |

36 |

|

OTC |

0 |

90 |

|

Life-style |

100c |

92 |

|

Formularies |

||

|

Closed or partially closed |

18 |

|

|

Open-preferred |

100d |

33 |

|

Open-passive |

38 |

|

|

No formulary (PA) |

13 |

|

|

No formulary (DUR) |

1 |

|

|

No formulary (free access) |

0 |

|

|

Closed formularies that contain only one drug in the drug class |

100 |

3.5 |

|

Drug restrictions (specific prescribers, settings, disease conditions) |

100 |

71 |

|

Required use of generic drugs |

100 |

38 |

|

Nonformulary |

||

|

Coverage of nonformulary |

100e |

100 |

|

Copay to influence choice |

0 |

100 |

|

Cost containment |

||

|

Limits on number of Rxs per patient at any time |

0 |

23 |

|

Limits on refills |

0 |

46 |

|

Limits on duration of use of some drugs |

0 |

21 |

|

Limits on the supply of drugs per Rx |

100 |

71 |

|

Presence of a PA process for some drugs |

0 |

53 |

|

Waiting period requirements for new FDA-approved drugs |

100f |

6 |

|

Six months or more wait period |

100f |

1 |

|

Active monitoring of new FDA-approved drugs: |

||

|

Drugs for the treatment of AIDS or cancer |

100 |

71 |

|

FDA “1P” drugs |

0 |

34 |

|

Appeals process |

||

|

Internal appeals process for excluded drugs |

100 |

47 |

|

Internal appeals process for nonformulary drugs |

100 |

19 |

|

Independent external review of appeals process |

0 |

7 |

|

Continuation of care |

||

|

Policy requires continuation of care for a few specific drugs |

0g |

3 |

|

Policy requires continuation of care for all drugs |

0g |

9 |

|

NOTE: DESI = Drug Efficacy Study Implementation; DUR = drug utilization review; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; PA = prior approval; 1P = FDA priority; P&T = pharmacy and therapeutics. aReflects the composition of VISN formulary (P&T) committees. b The VA does not cover experimental drugs but it does not preclude the use of experimental drugs in its research programs. c The VA does not exclude any class of drug, but if a specific agent is not on the formulary, it must be accessed by the nonformulary process. d The VA formulary is a composite of a closed open–preferred, and open–passive formulary. The 100% for veterans should be compared to the summation of these three types. e When medically justified. f In some VISNs, drugs can be placed on the formulary earlier than 1 year. gThe VA does not have a specific policy for continuation, but a nonformulary drug can be continued if approved through the nonformulary process. SOURCE: Private health care data from Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. |

||

Adequacy of the VA National Formulary

With respect to the adequacy of the VA National Formulary, the committee asked several questions. Is the overall size of the formulary reasonable? Are the closed classes limited to a reasonably small number for which economic and

|

BOX 2-1 Formulary and Formulary System Limitations or Other Restrictions on Drugs in a Health Care System

|

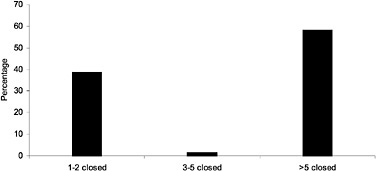

FIGURE 2.1 The number of closed classes in closed private-sector formularies by percentage of private-sector plans. SOURCE: Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (2000).

therapeutic effects justify the effort (and possible inconvenience to prescribers and risks to patients) of managing that class? Are the numbers of members in a closed class listed on the formulary reasonable and sufficient, particularly in comparison with other formularies? The standard of reasonableness depends in part on the committee's professional judgment and experience with other formularies and in part on information in studies and reports in the scientific literature.

The overall size of a formulary is not necessarily a key characteristic. There is no standard that specifies a particular size for a given health care system. Large open formularies may contain from 1,000 to 3,000 drugs and dosage forms (Covington and Thornton, 1995). Those of the Mayo Clinic and the British National Formulary list more than 1,200 and 2,000 items, respectively. In 1997, most MCO formularies (60%) contained less than 1,000 items, and 37% were in the 750–999 category (Hoechst Marion Roussel, 1998). A majority of MCO formularies were closed or partially closed (Novartis, 1999).

A more open formulary that includes greater numbers of widely prescribed drugs does not automatically improve clinical practice. In studying Medicaid formularies after OBRA 1990, which traded drug rebates for abolition of restricted formularies, Walser et al. (1996) concluded that only 22% (4/18) of additions of top 200 drugs to state formularies conferred a net therapeutic benefit, that is, led to better patient compliance, were less expensive, or had greater effectiveness, according to panels of practicing physicians. The rest either were questionable or did not offer an additional benefit. The authors could not draw any policy conclusions from these data. Many drugs are widely prescribed because prescribers are influenced by industry sales techniques or for other non-scientific reasons (Avom and Soumerai, 1983; Avorn et al., 1982; Schwartz et al., 1989), or because patient demand is generated by direct-to-consumer adver-

tising (Barents LLC, 1999a; www.imshealth.com/html/news_arc/06_07_1999_211.htm).

Rucker and Visconti apparently considered that a good-quality hospital formulary listed only about 450 single drugs, but their reports are dated, and in any case apply to a hospital, not a health care system (Rucker, 1982b; Rucker and Visconti, 1978). In 1986, Bakke reviewed the situation internationally and concluded that at that time, about 500 drugs should be available to deliver good care in most advanced countries (Bakke, 1986). This estimate is primarily of historical interest given its age and the fact that it was devised for countries not health care systems. Rhode Island Hospital, the principal teaching affiliate of Brown University, was reported to have 580 medications listed in its formulary in 1986 (Packer et al., 1986). In a review of survey data from 187 large, private, nonprofit, U.S. teaching hospitals, Mannebach et al. (1999) noted that most of their formularies were closed and that P&T committees tried, for the most part successfully, to limit the numbers of drugs listed in therapeutic classes.

The VHA allows VISNs (and local facilities) to add items that are not on the National Formulary. Therefore, choices actually available on these formularies (although the same in at least one instance, VISN 14) usually exceed those on the national list by a few to 544 items. VISN formularies frequently include about 10% more items. Precise formulary comparisons are difficult because the VISN formularies list multiple dosage forms and the National Formulary does not. One formulary for which precise figures were provided (VISN 19) contained 108 more drugs and a total of 615 different drugs.

|

Prior to the VA National Formulary, some VISNs were functioning at 70% or less of the present National Formulary size. |

Most VA local and VISN formularies had fewer listings before the national list was introduced in 1997. Some of these facilities were operating, apparently satisfactorily, with a formulary of 70% or less the size of the present National Formulary (VHA data provided to IOM, 1999). In view of the increase in drugs and drug products available to veterans since the introduction of the National Formulary and in comparison to MCO or hospital formularies, the number of items on the VA National Formulary seemed reasonable to the committee.

Closed and Preferred Drug Classes in the VA

The VA National Formulary's closed classes, the quality of the listings as affected by the quality of the input of P&T committees, the MAP, and VA PBM (see Chapter 4 of this report), and the access afforded through a nonformulary exception process are probably more important measures of restrictiveness than overall formulary size. Although dozens of therapeutic classes have been or are being reviewed by the VHA, only six classes (four at the present time) have been closed. Two classes are preferred, that is, they are open, but there are national contracts for one or more members of the class.

The closed classes, identified in this report's introduction, are (ACEIs), (HMG CoA RIs), (LHRHs), and (PPIs). They comprised about 16% of the prime vendor cost of drugs in 1998, and, because the VHA accounts for the great majority of prime vendor sales, probably about 16% of VHA drug costs in that year. According to GAO, they comprised 13% of drug costs in 1999 (GAO, 1999). * Because there are only about 20 chemical entities in these classes —that is, about 2% potentially (if expected new entries and different routes of administration and dosage forms are included), and less than 1% in reality, of the drugs on the National Formulary—these classes have an economic impact disproportionate to their numbers. This reflects their prices and the importance of their therapeutic effects; the prevalence of the conditions they can treat, especially in the older, almost all-male VA population; and the volume of prescriptions written for them. In fact, nationally, three of these closed classes were in the top five classes accounting for drug expenditure increases and the top seven in class cost in 1998 (Barents LLC, 1999a). According to the last Novartis (1999) survey of MCOs, gastrointestinal medications (such as PPIs), ACEIs, and HMG CoA RIs were in the top five classes by overall cost, number of prescriptions, and per-member per-year expenditures in managed care pharmacy benefits. The closed classes are clearly important, major classes (see also Figure 2.1 for comparison of number of closed classes in PBMs that close classes).

Preferred classes are also contributors to drug costs and utilization. As noted, there are two preferred classes (CCBs and alpha blockers), one of which (alpha blockers) was previously closed. The case for creating preferred classes may not be quite as persuasive as that for closed classes. In theory, more local options are provided in these classes because VISNs and facilities are free to supplement the national list. However, economics drive the choice to the nationally contracted drugs in the preferred class and may encourage changes in prescribing by physicians or initiate therapeutic interchanges. A previously closed class, (H2R) blockers, is open since some members are now generic and famotidine, cimetidine, and ranitidine are OTC. Price or cost control in this class is also exercised through contracting, which has a striking effect on utilization (see Figure 4.4, Chapter 4 of this report).

National usage criteria that generally depend on therapeutic guidelines or drug class reviews are also issued from time to time by the VA PBM. There were nine separate usage criteria in the fall of 1999 (http://www.dppm.med.va.gov/newsite/criteriadrop.html). These criteria may require certain patterns of prescribing or even therapeutic interchange. They may also dictate the ways in which nonformulary drug products (for example, new anti-inflammatory agents, such as cyclooxygenase-2 [COX-2] inhibitors), can be used acceptably for arthritis and other conditions. In encouraging such behavior, preferred classes, those with national usage criteria, or those with committed-use contracts are similar to closed classes, although they are officially open.

|

* Based on 1998 prime vendor purchase data, the projected fifth closed class (oral 5HT3 RAs) would account for less than 0.5% of the top 200 VA drug costs. |

After VA drug class review, six classes that were reviewed for possible closure have not been closed, preferred, or subjected to restrictions at the national level, although they might have been. Such classes, which are often managed (closed, restricted, or subject to therapeutic interchange) in other health care systems, include some drugs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], other antidepressants) used in mental health care or expensive antibiotics (for example, fluoroquinolones or cephalosporins) (Achusim, 1992, reviewed in Bootman and Milne, 1996; DeTorres and White, 1984, reviewed in Dunagan and Medoff, 1993; Dzierba et al., 1986; Edwards and Anderson, 1999; Guze, 1996; Kresel et al., 1987, reviewed in Mitchell et al., 1997; Nightingale et al., 1991; Reeder et al., 1997; Stock and Kofoed, 1994; Streja et al., 1999; Zhanel et al., 1989). MCO formularies also often restrict expensive, brand name products through higher copayments (Hoechst Marion Roussel, 1998; Smith, 1993).

Drugs in VA closed or preferred classes, although not chemically identical, are similar in therapeutic effect. Price differentials exist among class members. Generics are few or absent, and significant price reductions and aggregate savings through volume commitments are possible (see Chapter 3 of this report). These same classes are also subject to restrictions and therapeutic interchange in other (MCO) systems. Restriction to a few choices through closure or preference in each class is reported to be consistent with good care because class members are thought to be therapeutic alternates. That is, they have similar therapeutic effects based on the available medical evidence (see VHA class reviews and accompanying references at http://www.dppm.med.va.gov/newsite/reviews.html ; see also Briscoe and Dearing, 1996; Gerbrandt and Yedinak, 1996; Hilleman et al., 1997; McMillan, 1996; Moisan et al., 1999; Oh and Franko, 1990; Petitta et al., 1997).

Potentially closed or preferred classes that are not economically significant, are low volume, have many generics, or have no comparatively substandard members may not yield economic or quality rewards from being designated as closed or preferred that are sufficient to justify the time, effort, and potential prescriber and patient dissatisfaction involved. Classes for which quality concerns would be raised by a designation as closed or preferred definitely should not be so designated (Carroll, 1999). These classes are not closed or preferred in the VA National Formulary.

Restrictiveness of Class Closure

The VA National Formulary has some classes with only a single agent, which is unusual in other formularies (see Table 2.1 and discussion of some MCO formularies and Medicaid in Chapter 5 of this report). These may be classes with only one or two members, such as chloramphenicol or PPIs (at the time of original listing). If the classes are open, facilities and VISNs are free to expand the listings. Listing only a single drug in a class is not prima facie evidence of excessive restriction, but it tests the ability of the nonformulary process to provide access to therapeutic alternates if medically needed. The absence of

formulary alternatives (if such drugs exist) deserves examination. It is unlikely that a single member of a multidrug class will treat all patients for whom the class is indicated without exception (McAllister et al., 1999), and some investigators have reported that restriction of choice to a single agent compromises care and raises costs (Streja et al., 1999). Therefore, a smoothly functioning non-formulary process is important to preserving quality of care in this situation.

The listing of only one agent in closed classes, such as PPIs and LHRHs, results in almost all veterans being on the formulary agent lansoprazole or goserelin (see Figure 4.2 and Figure 4.3 in this report). All four potential choices (as of July 1999), including nonformulary omeprazole and leuprolide, are on the 200 top dollar expenditure list, however, so nonformulary costs are at least measurable. In general, VA nonadherence reports identify about 5% nonformulary dispensing in closed classes with a single formulary choice. Decisions on PPIs and LHRHs were made on the basis of good-quality drug class reviews (see Chapter 4 for analysis; for actual reviews, see http://www.dppm.med.va.gov/newsite/reviews.html). There is also a specific VA cost-effectiveness study that compares PPIs (Vivian et al., 1999). The VA nonformulary exceptions process is discussed briefly below and in Chapter 4 of this report.

In a lengthy review of restrictive formularies, many of which are also reviewed in Chapter 5 of this report, Levy and Cocks (1999) claimed that the VA National Formulary severely limits choice among brand name agents in six drug classes, three of them current VA National Formulary closed classes. These authors provided no evidence of effects on veterans' health outcomes by National Formulary restrictions in these classes. Although Levy and Cocks (1999) raised some interesting concerns, some of which are discussed further below, the committee concluded that they had not made a persuasive case for meaningful and severe limitation of choice in the six cited classes.

Median coverage by 13 Medicaid programs was 27 of the 27 brand name products in the six classes, and by the National Formulary, 8 of 27. It is not clear that these Medicaid programs are representative, and in any case, states must include in their Medicaid formularies all drugs that manufacturers list in the Federal Supply Schedule. Of four cited National Formulary classes with only one representative, three are either open or preferred so that VISNs and facilities are free to add drugs that are used and preferred locally. The other class, PPIs, which is closed, had only two brand name products (additional products have since been marketed) from which to choose, and they are considered therapeutic alternates (Chon and Suzuki, 1998; Vivian et al., 1999; see also the VHA drug class review and its accompanying references at http://www.dppm.med.va.gov/newsite/reviews.html). A VA drug class review recommended one nitroglycerin patch in that open class, based on cost and patient preference since available products are similar and, with the exception of a few high-dose patches, are rated bioequivalent by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 1999a). The other two classes (alpha blockers and H2R blockers) are currently represented by two (prazosin, terazosin) and three members (cimetidine, famotidine, ranitidine), respectively.

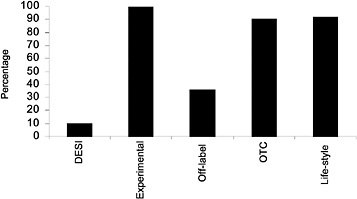

FIGURE 2.2 Drug categories excluded by percentage of private-sector plans. DESI = drug efficacy study implementation; OTC = over the counter. SOURCE: Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (2000).

Excluded Drugs and Other Limits

The VA, with extremely rare exceptions, does not use controls such as exclusions or volume limits, some of which, without medical necessity-based exceptions, are among the most restrictive (see Box 2.1). Although almost all state Medicaid formularies are open, they all exclude some drugs, for example, one or more of anorexiants, hair growth and other cosmetic drugs, fertility drugs, male impotence drugs, smoking cessation drugs, all or some OTC drugs, all or some drugs listed in OBRA 1990 (see Glossary), Drug Efficacy Study Implementation (DESI) drugs (see Glossary), and the like. States are free to make drugs subject to prior authorization, and most do to some extent. States also frequently restrict quantity dispensed, number of prescriptions per month, or number of refills, without providing exceptions for medical necessity (see Chapter 5 for details; see also National Pharmaceutical Council, 1997, 1998; Walser et al., 1996).

In general, the VA National Formulary is restricted in ways that support price negotiations and direct prescribing to the best-price drugs. This is true of MCO and PBM formularies too (although they also exclude certain drug categories as shown in Figure 2.2). Such restrictions are not as effective for Medicaid formularies or state policies because drug price discounts or rebates are already specified in federal statute. The congressional decision to require a relatively open Medicaid formulary (but allow prior authorization and exclusions) reflects the agreement on best-price manufacturer rebates rather than an analysis of the pros and cons of formulary structures (Walser et al., 1996). Medicaid formularies use restrictions to control expenditures not prices, as noted above, and they vary considerably from state to state.

National Formulary Effects on Drug Use

The VA National Formulary in closed classes and the national contracts in closed and preferred classes have marked effects on drug utilization. The use of VHA nonformulary or noncontract agents is close to zero in many cases (see, for example, PPI utilization data for omeprazole, Figure 4.2). In closed classes with national committed-use contracts, where Contract Adherence Reports identify that a VISN's nonformulary drug use is greater than two standard deviations above mean VHA nonformulary drug use, this is brought to the attention of the VISN. Apparently, VHA policy is to encourage corrective action through repeated contacts if adherence does not improve (VISN 13 P&T committee minutes, May 5, 1999). In the case of VISN 13, national use was 96.5% lansoprazole; VISN 13 use, 93.6%. A requirement that VISNs submit quarterly reports justifying nonformulary drug use (VHA Directive 97-047) was not implemented because the VA PBM decided that the value of these data was insufficient to justify the cost of gathering them given the high level of contract and formulary adherence. For their part, VISNs report that they do not have formal sanctions for nonadherence by local facilities. Their policy appears to be to bring this to the attention of responsible officials or physicians at the local facility and discuss plans for correction. This is reported to be effective. As noted elsewhere, the percentage of nonformulary drugs dispensed by MCOs with formularies is 10% nationally (Hoechst Marion Roussel, 1998).

Whether the VA National Formulary is overly restrictive relative to managed care experience probably depends on factors other than the actual size of the formulary or number of choices listed in important drug classes. These elements are not dramatically out of line with experience in other health care settings. Managed care systems use some controls not available to the VHA. The committee argued that the National Formulary, if supported by an administratively flexible and responsive nonformulary process, might be, in practice, less restrictive. Low-income veterans might have better access in such a system than in one that assessed financial penalties for the use of nonpreferred or nonformulary drugs.

The VA National Formulary serves numerous settings in addition to hospitals, so it is not strictly comparable to hospital formularies. However, it appears not to restrict choice in major or closed drug classes more than the average American hospital according to Mannebach et al. (1999). In 1995, these authors surveyed pharmacy departments in 187 large, private, nonprofit, U.S. teaching hospitals. Surveyed pharmacists were asked what drugs in three large popular classes (all three either currently or formerly closed in the VA National Formulary) were listed on their hospital formularies. On average, these formularies listed 3.3 ACEIs, usually captopril, enalapril, and one other; 1.8 HMG CoA RIs, usually lovastatin; and 2.3 H2R blockers with no predominance of either cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine, or ranitidine. Current National Formulary listings in these classes are very similar. They include captopril (as a generic), fosinopril, and lisinopril in ACEIs; lovastatin and simvastatin in HMG

CoA RIs; and cimetidine, famotodine, and ranitidine in H2R blockers. Therapeutic interchange programs in these classes are occasionally reported from nonfederal U.S. hospitals (Berkowitz, 1992; Briscoe and Dearing, 1996; Calvo et al., 1990; Fudge et al., 1993; Hilleman, 1997; McDonough et al., 1992; Oh and Franko, 1990).

As discussed earlier, the National Formulary's restrictiveness may depend, therefore, on the closed classes, national committed-use contracts, and the additional choices in open classes in VISN and local formularies. A smoothly functioning, responsive nonformulary exceptions process, especially for drugs in the closed classes in which most VISN formularies lost options in 1997, would substantially mitigate any untoward effects of these restrictions.

ADDITION OF NEW DRUGS AND FORMULARY REAPPRAISAL

National Policy Regarding New Drugs

Under current policy, drugs newly approved by the FDA are considered for addition to the VA National Formulary only after a 1-year delay, except in special cases of important new 1P category drugs, that is, new chemical entities classified for priority review by the FDA (VHA Directive 97-047). Formulary drugs should be selected with priority based on their relative therapeutic merits. The FDA is aware of the relative merits of drugs. The agency designates some drugs 1P for priority review because they are helpful in important diseases or conditions. The FDA also occasionally takes regulatory actions against misleading advertising claims of relative efficacy (Furberg et al., 1999). The agency, however, approves drugs based on their safety and efficacy, not their relative safety and efficacy compared to other available products. If there are a number of drugs in a class, P&T committees have an obligation, based on their best medical judgment, to select from among them those that are relatively as safe and effective as, or safer and more effective than, other members (much as those who sell drugs would like to see every possible member included). P&T committees also can take note of FDA 1P drugs in considering additions to formularies since these drugs may have particular importance, at least as seen by that agency.

In practice, the VA national policy has meant that new drugs for the treatment of HIV/AIDS have been added with less than a year lag, whereas other 1P drugs have been added only after a year or more, if at all. At present, these decisions are officially made by a consortium of the MAP, VISN formulary leaders, and the VA PBM. Although the final authority was vested initially in a VA PBM Executive Steering Board made up of officials from various units of the VHA central office, this board never became operational. As opposed to the policy of delay in additions of newly approved drugs, the committee did not find any policy of specified periodic internal review or external evaluation of the National Formulary.

The VHA policy of a 1-year waiting period is considered a safety precaution that allows evidence of adverse drug effects to accumulate during the interval. It also provides time to carry out studies comparing the safety, efficacy, or cost-effectiveness of new drugs with existing therapeutic alternates or drugs for similar indications. Such studies are usually not done during the FDA new drug approval process. Data, especially in the peer-reviewed open literature, to inform a decision on whether a new drug is an improvement over, or an addition to, existing drug therapies are generally not available until some time after release, if at all. In fact, Sloan et al. (1997) noted a dearth of phamacoeconomic or cost-effectiveness studies even beyond a year after market entry of new drugs. Waiting for a year does not guarantee that adequate comparative evaluations will be available (Lyles et al., 1997; Mather et al., 1999; see also VA drug class reviews at http://www.dppm.med.va.gov/newsite/reviews.html).

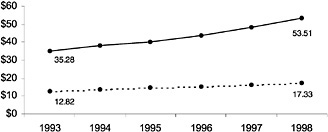

The VHA has cited reports of adverse effects and even FDA recall or restrictions that may occur with experience in the general population. Examples, such as troglitazone and mibefradil, which were not added to the National Formulary, have been given (VHA answers to IOM questions, 1999, but troglitazone was widely used in the VHA). According to the FDA (Federal Register 64[44], March 8, 1999; Federal Register 65[2], January 4, 2000), 15 agents were recalled in the 1990s, 10 of these since the National Formulary was implemented in mid-1997. Some of these drugs were not on the market, for example, antipyrine; were recalled much more than a year after entry, for example, terfenadine [Seldane]; were not 1P drugs, for example, fenfluramine (Pondimin); or were, in fact, on the National Formulary, for example, cisapride (Propulsid). Also, new drugs are generally more expensive. Therefore, in addition to safety considerations, there are significant budgetary implications in delaying the addition of new drugs to the National Formulary. For example, 1998 prices of drugs approved between 1992 and 1998 were significantly more than the 1998 prices of pre-1992 drugs (Barents LLC, 1999b; CBO, 1998; Levit et al., 1998).

VISN Addition of New FDA Approvals

New FDA approvals can also be added at the VISN level and, when local formularies are different, separately at that level also. VISN policies on adding new approvals vary but in general appear more permissive. For the most part, they do not require a 1-year waiting period, although a few do. Most VISNs await and react to activity at the local level. An occasional VISN reviews new approvals proactively if they are high-profile drugs. A few local facilities can add drugs and may also request their consideration for the VISN formulary. Prescribers can formally ask for additions, either of newly approved drugs or of existing drugs, to the local, VISN, or—through VISN formulary leaders—to the National Formulary. Many VISNs have standardized forms for such requests that require scientific analysis and justification. These requests are reviewed and approved or denied at the appropriate level. Drugs not reviewed at the VISN

level because of a 1-year VISN waiting period for new approvals, may be added provisionally by local facilities in some regions. Drugs are always potentially available through the nonformulary process, and in such cases, access depends on the smoothness of this process. These data are summarized in Table 4.1 of this report.

The MAP, VA PBM, and VISN formulary leaders can bring up National Formulary changes on their own motion at any time. Important to this process are the drug class reviews on which approvals or disapprovals of many additions are based. As discussed in Chapter 4, these reviews are of good quality. Although they refer to cost or cost comparisons fairly often, they only occasionally (for example, SSRIs) have separate sections on pharmacoeconomics or cost-effectiveness. Separate pharmacoeconomic analyses are frequently not part of reviews in other settings either (Grabowski and Mullins, 1997; Gross, 1998; Lyles et al., 1997; Sloan et al., 1997).

Evaluation of the VA Process for Adding New FDA-Approved Priority Drugs

The committee reviewed the 42 FDA 1P drugs approved in 1996, 1997, and 1998. Ten of the 1P drugs that were introduced before the implementation of the VA National Formulary were included in the initial version. Four drugs were subsequently approved and added, primarily for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. By July 1999, the 28 remaining 1P drugs either had been reviewed and not approved (5), had not been reviewed (21), or were pending (2). The reasons for disapproving additions included “no advantages over contract agents,” “evidence regarding efficacy was inconclusive,” and “safety/cost concerns.” At the same time, the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research 1998 Report to the Nation (http://www.fda.gov/cder/reports/rptntn98.pdf) proposed that 1P drugs “represent an advance in medical treatment” and described a number of the drugs that had been disapproved or not reviewed by the VHA as “notable 1998 new drug approvals.”

The MAP, VA PBM, and VISN formulary leaders must employ stringent evidentiary requirements for the addition of newly introduced drugs, since few are added to the National Formulary. As far as the committee could determine, however, there is no VHA policy or practice of identifying and reviewing new 1P drugs (for example, the 21 “not-reviewed” 1996, 1997, or 1998 1P drugs) or other new-to-market drugs in a systematic way. As discussed in the preceding chapter, VISN and local policies and practices, although variable, appear to be more permissive. Many decisions on drug class reviews, therapeutic guidelines, and formulary additions are made in the professional judgment of the MAP, VA PBM, and VISN formulary leaders and are memorialized in the minutes of their meetings. From an examination of these minutes and observation of a MAP/VA PBM meeting in August 1999 by the committee and IOM staff representatives, these groups appear to be appropriately expert professionals functioning in a thoughtful manner. Nevertheless, existing or newly introduced drugs are less

likely to be added to the National Formulary than to the formularies of other organizations or to VISN or local formularies, and listed drugs are less likely to be deleted. One or more VISN or local formularies added 4 of the 5 disapproved 1P drugs and 4 of the 21 nonreviewed 1P drugs. In one case, 18 VISNs added clopidogrel (Plavix), a nationally nonreveiwed 1P drug. A decision was then made at the national level not to add this drug to the National Formulary, but it remained on VISN formularies.

Changes to these VHA formularies vary considerably from VISN to VISN. Obviously, as this continues over time, the role of the national list as a universal, uniform entitlement for veterans will be weakened while the role of the VISN list as an expression of local autonomy and choice is strengthened. This resolves the natural tension between a uniform, standardized national entitlement and local autonomy and flexibility, at least in part in favor of local preferences and loosened control. Of course, in theory, VISN or local formulary additions might not be needed given a very smooth, nationally consistent nonformulary process. The effect of VHA formulary management is a rather tightly managed national base of products and a more generous and decentralized drug policy at the regional and local levels. Inconsistencies in formularies (and other formulary system policies) also potentially expose veterans to inconsistent access and drug treatment in different VISNs.

The National Formulary disapproval of the (1998) FDA 1P drug sildenafil citrate (Viagra) for treatment of erectile dysfunction is undoubtedly an example of VHA concerns about cost. Although the committee did not carry out a detailed cost analysis, making this breakthrough drug available to veterans would clearly increase national VHA drug expenditures by tens of millions of dollars even at current federal supply schedule prices unless it was introduced with significant usage restrictions. Kaiser Permanente recently estimated that coverage of sildenafil would increase that health maintenance organization 's (HMO's) drug costs by $100 million annually (Mehl and Santell, 1999). Although this large group model HMO has about twice as many covered lives (more than 7 million) as the VHA, it also has a younger population with a normal male–female distribution (Navarro and Cahill, 1999).

Not everyone agreed with this noncoverage decision. By December 1999, the VA had developed and implemented criteria for the use of sildenafil. Before then, a VISN (VISN 15) and a few facilities in VISN 9, in clear noncompliance with National Formulary policy, added this drug to their formularies. VISN 15 had many initial requests for sildenafil, but approximately 25% of these patients did not refill their prescriptions. The VISN is currently examining whether this was due to lack of effectiveness in these clinical situations or some other reason, although preliminary results indicate that treatment failure was usually associated with hypertension. Noncoverage of sildenafil citrate generated congressional and Veterans Service Organization questions about formulary policy. VA national coverage of other products related to human sexuality, for example, male and female condoms, oral contraceptives, and other technologies to treat erectile dysfunction, is broader than that of most other formularies.

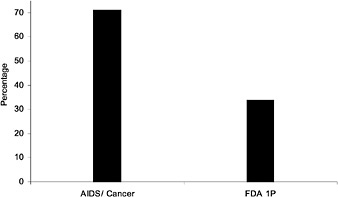

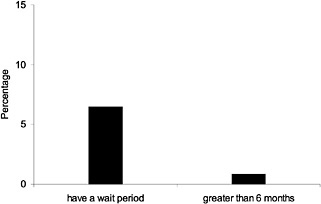

FIGURE 2.3 Percentage of private-sector plans having a mandatory policy of waiting before adding newly approved FDA drugs to the formulary. SOURCE: Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (2000).

Addition of Existing Drugs by the VA

After the National Formulary was established, about 260 different, mostly existing drugs were added to VISN formularies, usually only to one or a few VISNs, so that individual VISN formularies expanded by around 15 to 20 drugs or occasionally as many as 80 items over and above nationally required additions. Very few changes were made to the National Formulary in its second year of operation. National changes were primarily the result of completion of class reviews. Four of the five SSRIs and a few CCBs were added. A number of oral contraceptives were changed to generics, some corrections were made, and the antimicrobial levofloxacin was added while ofloxacin was deleted. In total, by the end of 1999, 26 drugs had been added and 6 deleted from the National Formulary (GAO, 1999). Many VISN formularies originally listed quite a few drugs in addition to these on the national list. If they continue to expand—and especially if they add newly approved new chemical entities and 1P drugs and the National Formulary does not—at some point, veterans who move from one VISN to another may encounter drug access problems, as observed earlier. This might be mitigated if the nonformulary exceptions process is operating smoothly and uniformly. It also raises issues of equity and could lead to veterans visiting VISNs to get drugs, which may already have occurred with sildenafil.

HMOs are said to be cautious about adding newly approved drugs to their formularies, in part because of cost concerns and in part because of quality concerns about direct-to-consumer advertising-driven demand for drugs that may not be the most appropriate for patients' conditions. Nevertheless, 20% of

HMOs reported adding new drugs immediately, and 62% have an established review period for newly released drugs, which is usually (74.2%) 6 months (Novartis, 1998). In 1997, about half of PBMs were found to have partially closed formularies; about half of PBMs imposed a 3- to 6-month waiting period for addition of new FDA-approved drugs to their formularies, and the other half added new FDA approvals immediately (Novartis, 1998). Recent data from the AMCP survey indicate even fewer PBMs and MCOs with wait policies and an even higher likelihood of review, and presumably addition, of new drugs (Figure 2.4 and Table 2.1).There do not appear to be any VHA policies on periodic complete formulary reviews or external evaluations, although additions and deletions to the National Formulary are posted on the Internet several times a year. Review of MCO formularies is carried out quarterly by 48% of plans and at least annually by about 85% (Hoechst Marion Roussel, 1998). Although the committee does not have aggregate data on the thoroughness or quantitative results of such reviews, based on the experience of committee members, they are detailed and consistent with standards in the literature (ASHP, 1981; Langley and Sullivan, 1996, Lipsey, 1992; Majercik et al., 1985). Some have recommended a thorough hospital formulary review perhaps every 3 years and evaluation by an external expert group every 4 or 5 years (Rucker, 1988).

FIGURE 2.4 Percentage of private-sector plans having a mandatory policy of waiting before adding newly approved FDA drugs to the formulary. SOURCE: Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (2000).

Addition of Newly Approved or Existing Drugs in Other Health Care Systems

The VHA policy of routinely waiting for 1 year after approval, the record of limiting expedited new National Formulary additions to HIV/AIDS drugs, and the addition of only 12.5% of new 1P drugs since inception of the National Formulary, is less generous than the policies and practices reported by private health care settings known to the committee (see Table 2.1 and Figure 2.3). Utilization management guidelines (UM 10 Procedures for Pharmaceutical Management) from the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) for MCO quality assurance require review of lists of preferred pharmaceuticals at least annually by actively practicing practitioners and, without waiting for requests, updating procedures as new pharmaceutical information is received. In discussing formulary decisions for a large and popular drug class in 38 HMOs, Bajpai and Pathak (1998) suggested considering formulary additions of new drugs 6 months after their introduction. Lyles et al. (1997) reported that more than half of the 51 HMOs they surveyed reviewed and assessed more than half of new drug introductions. In a smaller survey of HMOs with a 41% response rate, 29 HMOs reported that they covered on average 62% of 38 newly introduced drugs. Coverage was as likely to take place in the year of introduction as later on (Chinburapa and Larson, 1991).

A long lag in adding newly approved drugs and low percentages of these drugs added to formularies were not unusual in pre-OBRA 1990 Medicaid programs. An average lag of 20 months was reported by Grabowski (1988). Addition of newly approved drugs ranged from 19% to 73% between 1970 and 1980 (Schweitzer and Shiota, 1992; Schweitzer et al., 1985). One large program (California) required a 6-month wait at a minimum (Sloan, 1989), but this is no longer the case. Most state Medicaid formularies are now open. New drugs are added without much delay (as a result of OBRA 1990 and 1993), although prior authorization or other restrictions may be in force for some drugs. At present, Medicaid MCOs may add new drugs immediately. For example, the Common-wealth of Pennsylvania (HC-SW PH RFP No. 10-97), requires addition within 10 days of FDA approval (see Chapter 5 of this report).

In the survey report of Mannebach et al. (1999), hospitals added an average of 18.2 drugs in the 12 months preceding the survey and deleted 16.4. Included were both new approvals and drugs already on the market. These are more than were added to the VA National Formulary. They are consistent with the average changes in VISN and local formularies, however. In a much smaller (20-hospital) and older study, similar results were obtained. On average, 27 drugs were added to the formularies, and of 30 new FDA-approved unique chemical entities, 13 were added (Quigley and Brown, 1981). Most (78.4%) hospitals have formal procedures for formulary additions, although it is unlikely that many carry out a complete review each year (Rascati, 1992). Nevertheless, in a national survey of 103 (66% of 156 contacted) short-term, nonfederal hospitals, Sloan et al. (1997) found that more than 90% reviewed their formularies peri

odically for ineffective and obsolete drugs and for therapeutic categories with high risk, volume, or expense.

The committee agreed with the VHA that new drugs should not automatically be added to the National Formulary. On the other hand, as noted above, the committee found the evidence to support a blanket policy of an automatic interval of 1 year before such drugs were considered weak, and the results across the VHA and VISNs inconsistent, at best. At worst, this policy denies veterans access to some drugs the FDA finds significant, provides questionable protection from adverse events, and fosters a perception that it is a cost-based measure. Given that the VA has an expert MAP, a more thoughtful approach, in the committee 's view, would involve a policy of a prompt and careful assessment for inclusion on the National Formulary by medically qualified VA reviewers of newly approved drugs on their merits for veterans.

THE NONFORMULARY PROCESS

The nonformulary process and the policy that underlies it are discussed at some length in Chapter 4 of this report. The discussion is taken up here as well, because access to nonformulary products is integral to the restrictiveness of the National Formulary. There is no dispute that an exceptions process is necessary—in fact, vital—to a properly constituted and operating formulary system. Provision for access to therapeutic alternates makes sense clinically. Policy statements consistently include a nonformulary process as an essential component of a formulary system (AAHP, 1998; ACP, 1990; AHA, 1974; AMA, 1994; ASHP, 1983). Francke (1967) expressed this clearly and succinctly more than 30 years ago. “Formulate procedures for obtaining nonformulary drugs which are simple, fair and reasonable, and do not involve needless delays and complicated technicalities. ” A nonformulary process is also required by accrediting bodies such as the NCQA (UM 10 Procedures for Pharmaceutical Management—”an easily understood process to request an exception . . . in a time frame that is appropriate”) and the JCAHO.

The VHA has had nonformulary procedures in its facilities for many years. VHA Directive 97-047 set criteria for approving exceptions to the National Formulary and mandated that each VISN have a nonformulary process in place for VHA facilities in its region. The approval criteria include contraindications to, adverse reactions to, or therapeutic failure of the formulary on drug(s); lack of a formulary alternate; or previous response to, or stability of, a nonformulary agent. In 1999, based on its computer tracking of actual dispensing (which is likely to be accurate), the VHA reported that 3.45% of prescriptions were filled with nonformulary drugs (DVA, VHA Nonformulary Drug Use Process, 1999). Although the percentage contributions to expenditures of a number of popular nonformulary drugs in closed or preferred classes are on the FY 1998 list of top 200 dollar-expenditure drugs from the prime vendor (for example, omeprazole, pravastatin, atorvastatin, leuprolide, doxazosin), these do not add up to 3%, and

it is likely that VHA nonformulary drug costs as well as volume represent less than 5% of total costs or volume.

These VHA nonformulary volume or cost data appear relatively restrictive in comparison to data from hospitals and MCOs. Sloan et al. (1997) collected information on hospital self-rating of formulary restrictiveness, expenditures on nonformulary drugs, and monitoring of prescriber performance. They proposed that the restrictiveness of a hospital 's formulary was related, at least in part, to whether less than 5% of the drug budget was spent on nonformulary products (and to whether physicians were monitored for excessive use of nonformulary drugs). By this criterion, one of the few existing quantitative standards of restrictiveness, 60% of hospitals had restrictive formularies (Sloan et al., 1997). In MCOs, on average, 10% of prescriptions are filled with nonformulary drugs (Hoechst Marion Roussel, 1998).

In 1999, the VHA reported that the percentage of nonformulary volume in the VA National Formulary closed classes was between 4 and 6%. The just-noted lower overall nonformulary figure of 3.45% may therefore be somewhat misleading. It primarily reflects nonformulary use of the majority of drugs, which are in open classes where local preferences can influence expanded choice, and therefore lessened interest in nonformulary products at the VISN or local facility level. The 4 to 6% values presumably originate from contract adherence reports which show 5% or so nonadherence in some closed classes in some VISNs (see VISN 13 PPI nonadherence of 6.4% cited earlier, for example). These figures would be borderline indicators of restrictiveness by the Sloan et al. (1997) criterion.

In Chapter 4 of this report, the VA nonformulary process is reported to be often informal, unstandardized, and variable across VISNs and facilities. This assessment was based on one or more contacts to discuss nonformulary procedures and results with prescribing and/or pharmacy personnel in all 22 VISNs. VISN nonformulary request forms were examined when available. Nonformulary activity was described as often oral and unrecorded. The waiver request forms and processes were discovered to differ in administrative complexity in some VISNs. Not all VISNs had standard forms. The procedures for assessing and acting on a request appeared to require different amounts of time in different VISNs or facilities. A number of scenarios in which nonformulary drugs were prescribed or requested and no formal nonformulary record was likely to be maintained were explored with VISNs and facilities by IOM staff and confirmed. It was not possible to assess the frequency of any of these scenarios, however.

The committee appreciates that brief consultations between pharmacists and prescribers in clinical settings have ample historical and ongoing precedent (Gray, 1992). These consultations or informal telephone discussions with the pharmacy may represent the most rapid and efficient way to implement a nonformulary process and make nonformulary decisions for prescribers, pharmacists, and patients. Informal and unrecorded behavior may result in the distortion of VHA statistics and perceptions of uneven formulary enforcement, however. Such behavior is understandable in the case of discussions and advice in the clinic, perhaps less so

when oral requests are refused, and questionable when nonformulary prescriptions actually reach the pharmacy. Accordingly, the committee had reservations about VHA data on the total number of nonformulary requests, the percentage request approval or denial, or the time parameters for processing requests. As noted earlier, the VHA did not implement quarterly VISN written reporting justifying non-formulary utilization in classes where national standardization contracts have been awarded. Those reports that are made are oral, so the committee was also handicapped in assessing reasons for nonformulary use or denial.

In addition, reporting in the VA 1998 survey that the nonformulary process was easy or difficult to use came from physician P&T committee chairs. Data were collected and facilitated through the VISN formulary leader. Since “easy” and “difficult” are subjective characterizations reported by participants in the nonformulary request process to their central managers, these descriptions may mean different things to different people. In terms of administrative ease or time to completion, the committee was as concerned that there might be patient care settings with significant delays in response to requests for nonformulary drugs as with average response time. In some cases, the nonformulary process includes review by the facility's P&T committee. This means that requests could take considerable time to be approved or denied.

Therefore, the committee was not comfortable comparing details of the VISN nonformulary process with experiences reported by other systems. Available non-VHA hospital data on the number of nonformulary prescriptions or requests and the percentage of approvals are quite variable; some hospitals exercise tight controls, others essentially allow unchecked nonformulary use (Casio and Williams, 1982; Jay et al., 1993; Packer et al., 1986; Sloan et al., 1997). Prior authorization for nonformulary drugs is employed by 69 to 82% of MCOs and, for all purposes, by up to 90% of MCOs (see Table 2.1 and Figure 2.5). Some MCOs do not have formularies (or their formularies are not restrictive)

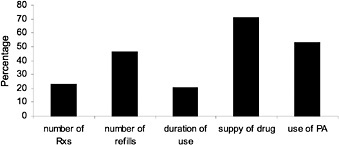

FIGURE 2.5 Limitations by percent of private-sector plans. NOTE: Number of Rxs = limits on the total number of prescriptions allowed per year; number of refills = limits on the number of refills per Rx; duration of use = limit on the length of time an Rx can be prescribed; supply of drug = limit on the quantity of drug the patient can have at one time (e.g., a 30-day supply); use of PA = requires prior authorization before drug can be prescribed and dispensed. SOURCE: Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (January 2000).

however, and many also control physician prescribing indirectly through variable copayments (Hoechst Marion Roussel, 1998; Novartis, 1999). About 80% of MCOs allow prescribers to override the formulary in some circumstances, and MCO or Medicaid rates of approvals of nonformulary or prior authorization requests vary from 70 to 90% or perhaps slightly higher (Hoechst Marion Roussel, 1998; Jones, 1998; Kreling et al., 1996; Phillips and Larson, 1997; Schweitzer and Shiota, 1992; Sloan, 1989). For HMOs, the result of formulary systems is that 90% of all prescriptions are filled with formulary drugs (Hoechst Marion Roussell, 1998), as noted earlier. In the experience of some committee members MCOs and PBMs are known also to have informal systems for considering non-formulary drugs (see also Table 2.1).

The reported VHA rate of approvals, 88%, may not include an unknown percentage of informal nonformulary approaches and subsequent rebuffs, as previously stated. The reported individual VHA facility percentages vary from 50 to 100%, but IOM staff discussions with local personnel suggest that approval rates may be lower if oral refusals are counted and that 100% approval rates may sometimes reflect reporting artifacts. Recorded counts of requests in the VHA 1998 survey varied from 2 per month to 718 per month, probably due to differing sizes of facilities, real differences in request rates, and different counting customs (Chapter 4 of this report). The committee observed that coincident with implementation of a new nonformulary request procedure, the reported number of requests in the facility recording 718 requests per month was reduced by half. In the current nonformulary system, some facilities may be reporting substantial undercounts.

The character of these data and the incomplete data from other health care settings impair assessment of the contribution of the nonformulary process to the restrictiveness of the VA National Formulary or comparison to the restrictiveness of other formularies. Variation in the process probably depends in part on local custom. Tension between medical staff prescribers and those responsible for pharmacy who understand that expanding drug budgets may obligate difficult savings in other budgets probably accounts for another part. Medical practice patterns, pharmaceutical sales activities, patient demographics, and other factors likely also play a role. Evaluations of the effect of the nonformulary process on restrictiveness could be supplemented by examination of prescriber and patient opinions (and complaints) and of policies, procedures, and outcomes regarding formulary-driven therapeutic interchange. These are discussed below.

Changes in the nonformulary process should be considered with a view toward providing better program data, improving prescriber and patient acceptance of the National Formulary, and softening perspectives on its restrictiveness. This will not be easy. As the National Formulary matures, and if compliance remains at high levels or even improves, a policy of retrospective interventions might be entertained. At least some pilot tests as proposed in Chapter 4 of this report should be considered. This would entail budget assignments and feedback to prescribers or follow-up corrective education on retrospective review and identification of prescriber patterns of excessive or medi

cally unjustified nonformulary use. Computerized data on drug utilization by prescriber could make this possible. This recommendation should not imply committee disapproval of reasonable formulary enforcement. Price negotiations will not be effective if prescribing is not directed to appropriately selected formulary drugs or drug products.

THERAPEUTIC INTERCHANGE

In managing the National Formulary and the pharmacy benefit, the VHA (with the National Acquisition Center) closes classes, and/or negotiates national standardized (committed-use) contracts or blanket purchase agreements with manufacturers for drugs in the classes or other classes, and/or issues national usage criteria or restrictions. In those situations, anticipated or promised volume supports better prices, which is, after all, one of the main rationales for the formulary. To achieve the promised volume (or market share) and realize the better price and, therefore, the savings, there is an expectation that VHA prescribers will discontinue using nonformulary or noncontracted drugs so that veterans are not started on these agents or that they may convert veterans from nonformulary or noncontracted drugs to the preferred or formulary agents. This expectation is no different than the expectation and practice in many U.S. hospitals and MCOs, as noted elsewhere. Interchange without individual prescriber permission at the time of dispensing is not uncommon in the VHA, however. Exchanges can be made by the pharmacy on authorization by the chair of the P&T committee without consulting each prescriber. The (prescribing and) dispensing by the pharmacist of a “therapeutically equivalent, ” pharmaceutically different drug than that prescribed for a patient by the physician (that is, therapeutic interchange with therapeutic alternates) is specifically authorized by the VA (VA Manual, M-2, Part 1, Chapter 3, Clinical Programs, Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, December 13, 1993).

Most therapeutic interchange in the VHA has been in closed classes or with a few popular drug products in other classes. These include situations in which there are price differentials, high volume, national contracts or usage criteria, current or former class closures, or VISN as well as national purchase agreements or contracts. In these situations the local facility, VISN, or VHA is anticipating target volume and target contract prices or responding to significant existing price differences to make savings in drug budgets (see reference to VHA reports below).

VHA investigators have published a number of reports describing therapeutic interchange programs in VA facilities in the 1990s. Additional reports have been presented at meetings but not published, and some less formal program data are also available. These reports often suffer from one or more of the following: small numbers, short follow-up, incomplete data and monitoring, and lack of controls, among others (Bartlett et al., 1996; Boston and Collins, 1995; Brunsting and Johnson, 1997; Cantrell et al., 1999; Desai et al., 1997; Edwards et al., 1998; Ganz and Saksa, 1997; Gray, 1999; Gustin et al., 1996; Ito et al.,

1999; Jones, 1999; Kellick et al., 1995; Kinnon et al., 1999; Lederle and Rogers, 1990; Lin et al., 1999; Lindgren-Furmaga et al., 1991; Minnich et al., 1997; Patel et al., 1999; Rindone and Arriola, 1998; Sprague and Gray, 1998; Stanaszek et al., 1997; Stock and Kofoed, 1994, Vivian et al., 1999). Therapeutic interchange in these reports, and in the VA in general, has been driven primarily by cost considerations (through contract and usage criteria adherence).

Some VA interchanges have been clinically successful (for example, see Boston and Collins, 1995; Cantrell et al., 1999; Ganz and Saksa, 1997; Jones, 1999; Kellick et al., 1995; Kinnon et al., 1999; Lin et al., 1999; Patel et al., 1999; Rindone and Arriola, 1998; Sprague and Gray, 1998: Vivian et al., 1999), but some have had clinical problems (for example, see Bartlett et al., 1996; Brunsting and Johnson, 1997; Desai et al., 1997; Minnich et al., 1997, Stanaszek et al., 1997; Stock and Kofoed, 1994). Economic outcomes have also been mixed because it may take time for the savings from a less expensive drug to pay back switching costs (Lindren-Furmaga et al., 1991), or savings from drug costs may have been offset by increases in other costs (Bartlett et al., 1996). On balance, however, most reports of therapeutic interchange have been encouraging, or at least reassuring, especially those describing more recent efforts.

A survey of 192 HMOs reported in 1988 that 30.5% used therapeutic interchange. Those that did not were concerned about physician dissatisfaction, interference with physicians' prerogatives to prescribe according to their best judgment, and the legality of substituting (Doering et al., 1988). Other surveys find that therapeutic interchange is an accepted practice in managed care that is becoming more prevalent each year. The Hoechst Marion Roussel survey (1998) reported 35.2% of plans allowing therapeutic interchange in 1997. Novartis (1998) reported that 47.7% of HMOs made use of therapeutic interchange in 1997; this survey projected an increase to 61.4% for 1999, and reported 56.5% of plans using therapeutic interchange in 1998 (Novartis, 1999). A survey of pharmacy benefits managers of employer plans in 1997 found 53.5% using therapeutic interchange (Wyeth-Ayerst, 1998).

The IOM committee noted that some of the VA drug classes involved in therapeutic interchange are also among those most often (more than 80%) subject to interchange in MCOs that practice interchange. These are antiulcerative (PPIs and H2R blockers), antihypertensive (ACEIs, CCBs, and alpha blockers), and cholesterol-lowering drugs (HMG CoA RIs) (Hoechst Marion Roussel, 1998; Wyeth-Ayerst, 1998). Some classes that are commonly controlled through interchange in managed care, such as expensive antibiotics, are left to local discretion by the VHA. Patterns of use also reflect local microbial resistance patterns. Other commonly interchanged classes in MCOs, such as antihistamines and anti-inflammatories, are limited to a few members in the VA National Formulary but are open to respond to local preferences at the VISN or VA medical center level (Hoechst Marion Roussel, 1998). Many of these classes are also reported involved in interchange in hospital programs. The committee concludes that they are also classes that have therapeutic alternates and price differentials, where therapeutic interchange is both medically and economically reasonable,

provided there is a provision for access to nonformulary therapeutic alternates when clinically necessary.

Therapeutic interchange has been carried out in hospitals for decades, and reports from hospital and other programs have been mostly supportive, reflect-ing experiences similar to those described by the VHA (reviewed in Achusim, 1992; Brown and Clarke, 1992; Bull et al., 1999; Green et al., 1989; Guastella, 1988; McAllister et al., 1999; Rich, 1989; Smith et al., 1989; Wall and Abel, 1996). Problems are pointed out in some of these reviews and elsewhere (for example, Barksdale AFB, 1998; Richton-Hewitt et al., 1988). Recent surveys, some of them quite extensive, find that therapeutic interchange is allowed or practiced in almost all U.S. hospitals (Nash et al., 1993 [76%, about two-thirds without notifying the prescriber]; Reeder et al., 1997 [74.5%]; Sloan et al., 1997 [79%]), and Mannebach et al. [1999] found that 69% of hospitals had formal therapeutic interchange policies).

Therapeutic interchange is supported by professional groups, provided the permission of the prescriber is obtained. As discussed earlier in this report, in hospitals and other well-controlled settings, such as some staff or group model HMOs, P&T committees in communication with the medical staff can design therapeutic interchanges. These interchanges are often implemented after ad-vance approval by the P&T committee and medical staff, or they can be specifi-cally approved by individual prescribers. In other health care systems, outpatient and less well controlled settings, PBMs, IPAs, and the like, the prescribers per-mission is almost always sought at the moment of interchange (ACCP, 1993; ACP, 1990; AHA, 1974; AMA, 1994; AMCP, 1997; ASHP, 1982; Lipton et al., 1999; Zellmer, 1994).

State laws on interchange vary in details to some extent. Washington is the only state that has specifically recognized therapeutic interchange, however, and has limited it to hospitals. States are consistent in requiring prescriber approval of therapeutic interchange. In controlled settings, this may be achieved according to protocols designed under collaborative practice agreements or other arrangements in which physicians are advised and approve (AMA, 1994). In hospitals, for ex-ample, physicians agree to abide by hospital policies and procedures when join-ing the hospital staff (Fink et al., 1998). MCO, PBM, and Medicaid providers must abide by state laws, but in a federal system like the VA, VHA policies on therapeutic interchanges (see below) preempt these state laws.

In theory, therefore, therapeutic interchange in the VHA does not appear re-strictive in comparison to other health care systems. Interchange is a common practice. It is used in relatively few therapeutic classes in the VHA, and these classes are often subject to interchange in hospitals and MCOs and are medically defensible. Articles in the medical literature from the VHA or elsewhere do not report serious problems with most interchanges. On the other hand, there are no national VHA guidelines on therapeutic interchange, and the committee did not find any written policies at the VISN level. Although interchanges may be initi-ated and specified at either the national, the VISN, or the local level, they are designed and implemented at the local facility level. As such, they respond to

local practices and need not be nor are they, consistent across the VHA. Some veterans subject to interchanges, when surveyed, report not having received adequate, or any, information on the replacement drug (see Chapter 4 ; W.N. Jones, personal communication, VISN 18, 1999). This suggests that informing veterans of interchanges could be improved even in VISNs that have experienced and thoughtful pharmacy leadership that tries to inform patients. Consideration might be given to having the responsible physician deliver the information in person.

Variation in some elements of therapeutic interchange to reflect local preferences and practice patterns may be desirable. Consistency in other elements might be important in ensuring program quality and patient and prescriber acceptance. In Chapter 1 of this report it was suggested that these elements might profitably include adequate advance notice and education on relative dosing and other factors for physicians and patients. Attention to patient compliance, provision for exceptions to conversion, and nonformulary access to an alternate or return to the original drug were also important considerations. Other elements included protections for at-risk patients, avoidance of frequent interchange or switching sick patients who were stable on a particular drug, and various methods of clinical and economic monitoring. The interchangeability of drugs in a class has to be evaluated with some care and expertise (McAllister et al., 1999). VA contracts are annually renewable. Drug prices, and therefore contracts, may change. At some point, the VHA will have to evaluate how frequently veterans taking a drug chronically should be subjected to interchange or the total number of interchanges that is reasonable in an individual patient. It is always important that interchanges may affect a stable drug treatment regimen, and from the veteran 's perspective are involuntary and may not be well understood.

Lacking national or regional guidance or convincing evidence of a flexible and responsive nonformulary process, therapeutic interchange programs in facilities may appear inconsistent or restrictive to prescribers and patients regardless of where they originate. Concerns about clinical monitoring, compliance, economic data, assessment of patient satisfaction, dosing problems, and varying observation periods were expressed in some published or unpublished reports of VHA therapeutic interchange (Bartlett et al., 1997; Brunsting and Johnson, 1997; W.N. Jones; personal communication, VISN 18, 1999; Lederle and Rogers, 1990; Minnich et al., 1997; Rindone and Arriola, 1998; Vivian et al., 1999). For the most part, they were of minor import, and the overall conclusions of most of these reports were reassuring.

Patient and physician complaints about the National Formulary and access to needed, or at least desired, drugs are often related to therapeutic interchange programs and indicate a level of dissatisfaction. Patient complaints about access to drugs are a very small fraction (0.4%) of veteran complaints to patient advocates. Physician surveys tend to reinforce the concern that some therapeutic interchange programs may appear, or in fact be, restrictive from the perspective of prescribers. Interchange without individual prescriber permission may lead to patient or prescriber dissatisfaction unless the setting is controlled and those