1

Introduction

CONTEXT

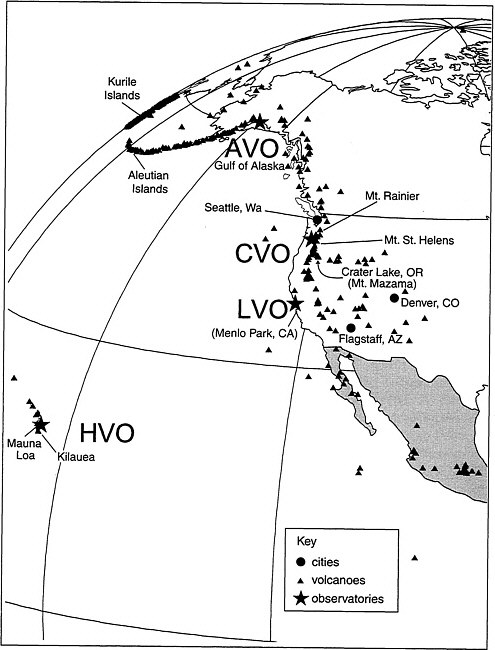

The United States has more than 65 active or potentially active volcanoes, more than those of all other countries except Indonesia and Japan. During the twentieth century, volcanic eruptions in Alaska, California, Hawaii, and Washington devastated thousands of square kilometers of land, caused substantial economic and societal disruption and, in some instances, loss of life. More than 50 U.S. volcanoes have erupted one or more times in the past 200 years (Figure 1.1). Worldwide, approximately 550 volcanoes have had historically documented eruptions; at least 1,300 have erupted in the Holocene (past 10,000 years) (Simkin et al., 2000).

Eruptions do not affect only the area immediately surrounding a volcano. Ashfall can devastate areas downwind; ash clouds from major explosive eruptions can threaten large numbers of aircraft along well-traveled flight paths especially across the North Pacific; and large eruptions influence global climate and agricultural production. Recently, there have been major advances in our understanding of how volcanoes work. This is partly because of detailed studies of eruptions and partly because of advances in global communications, remote sensing, and interdisciplinary cooperation (Simkin et al., 2000).

The study of volcanoes is both empirical and probabilistic. Scientists look at what has happened in the past and attempt to predict what will happen in the future. The same could be said about this study of the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) Volcano Hazards Program (VHP): determining the future of the VHP requires a combination of careful observations and educated projections. The hypothetical news releases in Prologues 1 and 2 represent two strongly contrasting views of the ways the VHP might respond to a large volcanic eruption in the year 2010. If hiring patterns, budget decisions, and other trends that are rooted in current policies of the USGS and the Department of the Interior (DOI)

continue, the results—as forecasted in Prologue 1—would be devastating. However, if the USGS is willing to make difficult changes in the VHP, then the number of casualties and the damage to the environment and the economy could be significantly reduced, as depicted in Prologue 2 and Chapter 6.

VOLCANO HAZARDS PROGRAM SETTING

The mission of the VHP is to “lessen the harmful impacts of volcanic activity by monitoring active and potentially active volcanoes, assessing their hazards, responding to volcanic crises, and conducting research on how volcanoes work” (USGS, 1997). The program has evolved in response to a variety of external pressures (see Sidebar 1.1). The first funding for studies of active volcanoes within the USGS budget was established in 1924 and went largely to support the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) (Figure 1.1). From the 1920s through the 1970s, most USGS volcanic expertise was directed toward understanding Kilauea and Mauna Loa volcanoes, and HVO became the premier site for the development of volcano monitoring techniques and protocols (see Sidebar 1.2). During this same period, USGS scientists on the mainland examined prehistoric volcanoes and volcanic deposits throughout the western United States as part of other assignments: mapping mineral deposits, looking for geothermal areas, cataloging the natural resources of National Parks and wilderness areas, and characterizing fluvial processes.

The Robert T.Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Act of 1974 (Public Law 93–288) states that “the President shall insure that all appropriate federal agencies are prepared to issue warnings of disasters to State and Local officials.” The director of the USGS, through the Secretary of the Interior, has been delegated the responsibility to issue disaster warnings “for an earthquake, volcanic eruption, landslide, or other geologic catastrophe.” Therefore, the USGS has the responsibility to issue timely warnings of potential geologic hazards to the affected populace and civil authorities. The Stafford Act placed a new emphasis on the VHP’s hazard mitigation role, which posed a challenge for the USGS.

|

SIDEBAR 1.1

|

|

SIDEBAR 1.2 The first 30 years of HVO provided the scientific and philosophical foundation for the present USGS VHP. Founded in 1912 by Massachusetts Institute of Technology Professor Thomas A.Jaggar, Jr., and located at the summit of the active volcano Kilauea, the observatory quickly became a center of renown for volcano monitoring and hazards mitigation. The HVO logo shown above, whose motto can be translated, “No more shall the cities be destroyed,” demonstrates the early commitment to volcano hazards mitigation, a major VHP objective today. HVO flourished during its first five years, but Kilauea’s gentle eruptions at the time were restricted to its remote summit crater, where no cities were threatened. In this time of relative quiescence, HVO staff studied molten basalt as it circulated in a summit lava lake, advancing knowledge of lava temperatures and gas content. Supported by private funds for its first six years, the observatory was operated by the U.S.Weather Bureau from 1919 to early 1924. The USGS took over management of HVO in June 1924, less than one month after explosions from Kilauea’s summit showered nearby areas with falling debris, killing one person who ventured too close and reminding all that the volcano was potentially dangerous. Reduced Depression-era budgets forced the USGS to relinquish administrative control of HVO to the National Park Service in 1935, but an improved postwar economy enabled it to regain control in 1948, where it has remained to the present. Hazards mitigation was HVO’s number-one priority during the 28-year directorship of Jaggar, a volcano zealot who preached the virtues of volcano studies as the best way to protect life and property. Jaggar retired from the HVO directorship in 1940, and wartime HVO managers struggled to keep the organization afloat. Kilauea slumbered until 1952, but its giant neighbor volcano Mauna Loa erupted from its summit in 1949 and again from its southwest rift zone in 1950. The later eruption sent rivers of lava that flowed at velocities of up to 8 km per hour, cut a major highway in three places, and poured into the sea. The citizens of Hawaii received an abrupt reminder that their volcanoes pose serious threats to life and property. USGS management responded by increasing the scientific staff of the HVO and initiating volcano hazards research in the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest. In 1968, the “Volcano Hazards Program” budgetary line item was formalized. |

Hawaii-based staff members had considerable experience dealing with volcanic activity, but this was for a limited range of eruptive styles. In contrast, the principal dangers to the western United States came from the explosive and effusive activity of stratovolcanoes and calderas, types of behavior not commonly observed in Hawaii. Thus, the sedimentologists, geochemists, and petrologists studying volcanoes in the western United States were asked to make predictions about future eruptions, even though the only, if any, activity most of them had seen was in Hawaii.

In many ways, the modern VHP was born when Mount St. Helens erupted violently on May 18, 1980. This was the first explosion of a mainland volcano since activity more than half a century earlier at Lassen Peak. The magnitude of the eruption and the range of its effects, especially the sector collapse and ensuing blast, were largely unanticipated, pointing out limitations in the expertise of VHP scientists, who had been drawn from both Hawaii and the mainland. Monitoring and describing this eruption gave a large number of geologists both inside and outside the USGS a tremendous boost in experience. Debris avalanches, pyroclastic airfalls, flows and surges, lava domes, and lahars could be studied in greater detail than ever before. The lessons learned at Mount St. Helens influenced the mapping of older volcanoes, emphasized the importance of process studies, and created a new appreciation among USGS scientists that exposure to as many active volcanoes as possible was an essential component of training for hazard mitigation at home.

The Mount St. Helens’ eruption led to a large increase in funding for the VHP, as well as to the establishment of the Cascades Volcano Observatory (CVO) in nearby Vancouver, Washington (Figure 1.1). Because many of the most significant hazards of ice-clad stratovolcanoes involve fluvial processes, such as mudflows and debris flows, CVO included scientists from the USGS Water Resources Division (WRD), along with a roughly equal number of members of the Geologic Division (GD). Although many individuals from the WRD and GD cooperate on specific projects, especially during volcanic crises, members of the two divisions tend to work on different types of tasks. Many GD scientists focus on mapping, assessing, and monitoring the hazards of specific volcanoes, whereas WRD scientists are more apt to work on quantitative modeling particular geologic or hydrologic processes.

In 1985, Nevado del Ruiz volcano in Colombia had a relatively minor explosive eruption that melted a glacier and generated mudflows

killing more than 23,000 people. Following this tragedy and building on the expertise gained at Mount St. Helens, the USGS and USAID set up the Volcano Disaster Assistance Program (VDAP), a well-equipped team of volcanologists and hydrologists able to respond to requests from foreign governments for technical and scientific assistance at the time of volcanic crises. Over the past 14 years, this relatively small team of scientists and technicians, based at CVO, acquired considerable experience through a series of deployments in the southwest Pacific, Africa, Latin America, and Alaska.

VDAP members’ increased knowledge of the behavior of explosive volcanoes helped make possible the establishment of the Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO) in 1988. AVO, a consortium set up by the USGS, the State of Alaska, and the University of Alaska, is charged with monitoring the active volcanoes of the Gulf of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands (Figure 1.1). Following a series of life-threatening encounters between jet aircraft and volcanic ash plumes in the late 1980s, the aviation industry recognized the risk posed by eruptions, especially along the heavily traveled North Pacific routes. AVO took on the role of providing timely warnings to airlines and pilots of any Alaskan eruptions capable of affecting aircraft safety. This responsibility has required AVO to gain better access to satellite-based remote sensing data, most of which originated from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It has also led to funding from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for seismic monitoring of Aleutian volcanoes.

In addition to HVO, CVO, and AVO, the VHP has a team comprising a “virtual” Long Valley Observatory (LVO). Based at the USGS Western Regional headquarters in Menlo Park (Figure 1.1), LVO tracks volcanic unrest in and around Long Valley caldera in eastern California. Long Valley is the site of the most recent rhyolitic activity in the lower 48 states, when approximately 600 years ago, lava domes, pyroclastic flows, and surges erupted from a fissure more than 11 km long. The caldera itself formed in a major explosive eruption approximately 730,000 years ago. Seismic activity and extensive ground deformation beginning in 1980 caused concern among residents of the town of Mammoth Lakes, one of the largest ski and summer resorts in California. LVO staff members have worked closely with local officials in establishing strong lines of communication to maximize public understanding of the evolving volcanic situation and to minimize panic.

Budget History

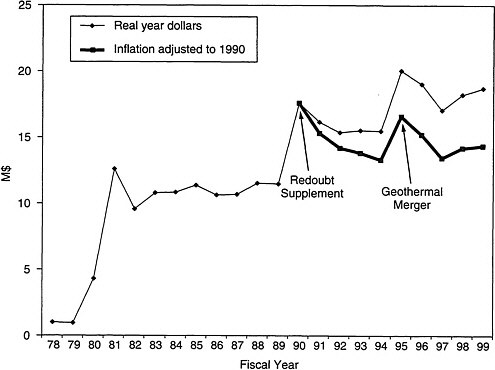

The U:S. Geological Survey is the nation’s largest integrated earth science agency and is the only science bureau in the Department of the Interior. The USGS is organized into four divisions (Geologic, Water Resources, Biological Resources, and National Mapping), with a total fiscal year 1999 appropriated funding level of $797.24 million. The VHP receives direct appropriations of $18.76 million (FY 1999). The overall funding for the VHP has increased slightly in real year dollars since 1978, but has remained flat since 1990 when adjusted for inflation (Figure 1.2), although responsibilities have increased in such areas as outreach, monitoring of Alaskan volcanoes, and international VDAP deployments. This decrease in buying power has caused significant hardship for the VHP and its ability to meet its public service mission today and especially in the future. The two peaks in funding in recent years trace to a supplement for the Redoubt eruption in 1990 and the merger of the Geothermal Program with VHP in 1995. The geothermal component of the combined program was cut substantially in FY 1996 and 1997, and much of the remaining geothermal project work was redirected to hazards studies.

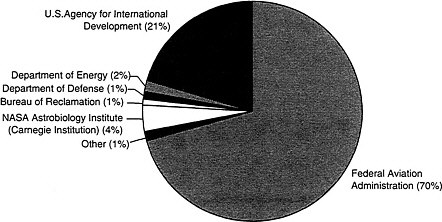

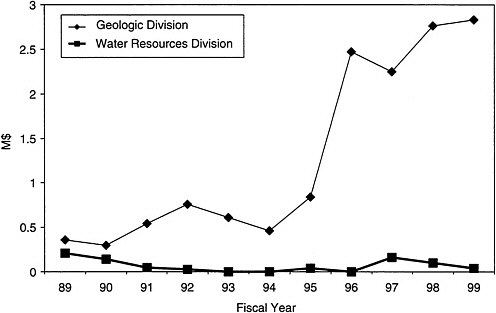

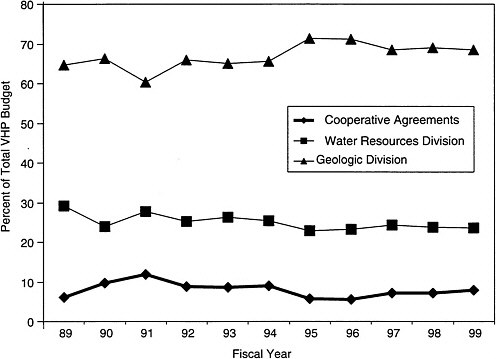

The VHP’s direct appropriations are supplemented by funds derived from other agencies under reimbursable contracts (Figure 1.3). In FY 1999, the VHP received $2.83 million of such funding, up substantially since 1995 (Figure 1.4). The VHP is funded jointly by the GD and WRD. In FY 1999, 68 percent of the VHP funding was spent within the GD, 24 percent within the WRD and 8 percent on cooperative agreements with state and university partners. These percentages have remained nearly constant since 1995 (Figure 1.5).

Staffing History

The VHP staff members are widely distributed in the western United States (Figure 1.1), working at three main observatories (Hawaiian, Alaska, and Cascades); one virtual observatory (Long Valley); and regional USGS offices in Menlo Park (California), Denver (Colorado), Flagstaff (Arizona), and Seattle (Washington). In 1999 the program had 135 full-time equivalents (FTE), with 35 in WRD and 100 in GD. Of these, 10 FTEs are supported by outside agencies under reimbursable contracts,

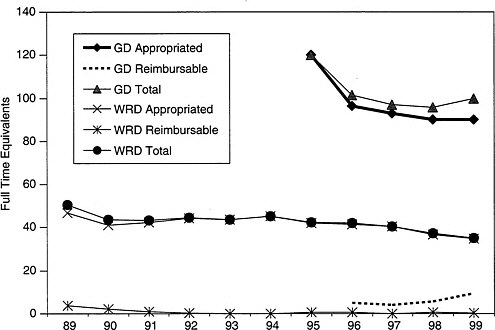

including 5 from the FAA and 4 from the USAID. The number of FTEs in GD has decreased significantly since 1995, whereas the number in WRD has decreased less dramatically (Figure 1.6). The GD has no data on program-staffing levels for the VHP before 1995. Prior to this time, staffing was accounted for by disciplinary branches, not by program funding sources.

Program Approaches

To help society prepare for and deal with the effects of volcanic eruptions, the VHP uses five interrelated approaches. (1) Long-term hazard assessment of the potential magnitude and timing of future eruptions requires documentation of a volcano’s past activity. A key challenge in assessment is deciding which volcanoes to study and how much detail such studies should seek. (2) Volcanoes that experience ongoing or recent activity require the monitoring of signals that might portend an incipient eruption. Monitoring demands the establishment of geophysical, geodetic, and geochemical baselines that allow premonitory changes to be recognized. (3) When an erupting volcano provides a direct threat to society, the VHP establishes a crisis response. A successful crisis response is characterized by rapid deployment of staff and equipment and by clear communication with civil defense officials and the public at large. (4) In addition to performing assessment, monitoring, and crisis response, VHP staff members conduct topical studies of geologic processes that allow for better understanding of the causes and consequences of volcanic hazards. (5) A final essential function of the VHP is to communicate to the civil authorities and the surrounding communities the results of its studies.

These five approaches all aim to help society respond to the dangers posed by volcanoes. Another way to view these activities is to consider a continuum of three overlapping types of societal response to eruptions: (1) Research (knowledge acquisition), (2) Operations (knowledge application), and (3) Outreach (knowledge translation). Research provides the basic information and concepts that underlie the various methods of volcano data collection and interpretation. Until the 1980s, the VHP accounted for much of the fundamental research on volcanic activity in the United States. More recently, scientists from universities and

Figure 1.6 Staffing levels in GD and WRD components of VHP.

the private sector have increasingly shared these functions. Operations refers to all of the work involved with direct mitigation of eruptions—assessment, monitoring, and crisis response. The VHP continues to be the principal source of nearly all of these essential activities in the United States and, through VDAP, is a significant contributor to similar efforts around the world. Outreach includes interactions with communities surrounding volcanoes. These types of responsibilities have grown in recent years, both for the VHP and for other agencies, although the VHP’s ability to maintain them has at times been hampered by insufficient funds. In evaluating the Volcano Hazards Program, perhaps the most basic question that USGS management must consider is, “What is the appropriate balance among research, operations, and outreach within the VHP, given changes in budgetary priorities and ancillary capabilities of other organizations?”

STUDY AND REPORT

To provide a fresh perspective and guidance to the VHP about the future of the program, the Geologic and Water Resources Divisions of the USGS requested that the National Research Council conduct an independent and comprehensive review. In December 1998, the Board on Earth Sciences and Resources within the Commission on Geosciences, Environment and Resources formed an ad hoc Committee to Review the U.S. Geological Survey’s Volcano Hazards Program. The committee consists of 10 geoscientists and volcanology experts from industry, academia, and county and federal agencies. Its members have recognized expertise in physical volcanology, geochemistry of volcanic gases and rocks, igneous petrology, geophysics, groundwater hydrology, remote sensing, geodesy, eruption prediction, volcano hazard assessment, emergency management, preparedness and response, risk communication, and science administration. Brief biographies of the committee members are provided in Appendix A.

Using the Volcano Hazards Program 1998–2002 Science Plan (USGS, 1997) as a starting point, the committee was asked to examine how the program is adapting to changes that have occurred as it has grown following the eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980. The charge to the NRC committee included the following questions:

-

Do the activities, priorities, and expertise of the program meet appropriate scientific goals?’

-

Are the scientific investigations and research results throughout the program effectively integrated and applied to achieve hazard mitigation?

The broad purpose of this examination is to provide fresh perspective and guidance to the VHP about its future directions.

A previous review of the VHP, chaired by Eugene Shoemaker, was conducted in 1986. That committee recommended, among other things, that (1) the level of effort for hazard assessment be increased; (2) seismic monitoring be conducted at several specific volcanoes; (3) an adequate professional staff in gas monitoring be maintained; (4) improved techniques for monitoring outgassing of CO2 be explored; (5) new instrumentation (sensors on Department of Defense satellites and microbarographs) for monitoring Alaskan volcanoes be evaluated; and

(6) steps should be taken to ensure interdivisional focus of effort in VHP. In 1990, the NRC Committee Advisory to the U.S. Geological Survey conducted a review of the status of the programs within the VHP (NRC, 1990). That committee also commented on the lack of effective coordination between the efforts of the two divisions, recommending a single program coordinator, and encouraged studies of volcanoes worldwide for knowledge that can be gained and subsequently applied where needed.

The committee held four meetings between March and August 1999. These meetings included presentations from and discussion with staff of the VHP and other USGS programs, representatives from local, state, and federal agencies, and academia. The committee also received written responses to questions about the VHP from stakeholders. Individuals who provided the committee with oral or written input are identified in Appendix B. As background material, the committee reviewed relevant USGS and VHP documents and materials through August 1999, pertinent NRC reports, and other technical reports and published literature.

This report is organized around the three components of hazards mitigation. Chapter 2 deals with research and hazard assessment. Chapter 3 covers monitoring and Chapter 4 discusses crisis response and other forms of outreach conducted by the VHP. Chapter 5 describes various cross-cutting programmatic issues such as staffing levels, data formats, and partnerships. Chapter 6 offers a vision for the future of the Volcano Hazards Program, and Chapter 7 summarizes the conclusions and recommendations of the preceding chapters. Throughout the report, major conclusions are printed in italics and recommendations in bold type.

The committee has written this report for several different audiences. The main audience is upper management within the USGS and the VHP. However, the committee believes that scientists within the VHP will also find the report valuable. The report is written in such a manner as to be useful to congressional staff as well.

An Early History of HVO and VHP

An Early History of HVO and VHP