4

Economist's View of Ecologically Based Pest Management

KATHERINE REICHELDERFER SMITH

Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture

The following comments are organized around five of the questions posed to workshop participants about the value and feasibility of interdisciplinary approaches to ecologically based pest management (EBPM) research.

HOW CAN ECONOMICS AND OTHER SOCIAL SCIENCES CONTRIBUTE TO INTERDISCIPLINARY EFFORTS AND EBPM?

Pest management is an intrinsically anthropocentric endeavor. There is no reason to manage pests other than the fact that the activity meets human needs and objectives. Decision models implicitly, if not explicitly, assume that the human pest management decision-maker is a central part of the agroecosystem being addressed. Economics, sociology, anthropology, and other potentially relevant social sciences are critical to understanding that central, human aspect of the ecosystem that is being managed. To ignore the human behavioral and economic influences on the ecosystem is to fail to fully evaluate decisions in an ecological context. Thus, it is almost a tautology to say that the social sciences contribute to EBPM.

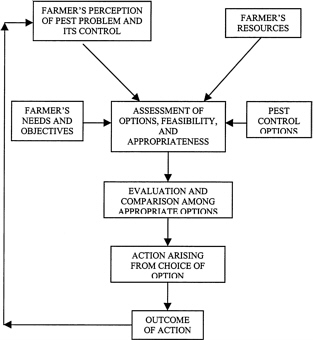

Figure 4-1 is a schematic diagram of the pest management decision-making process. It provides a handy mechanism for illustrating how research and development of pest management options require social–scientific concepts,

FIGURE 4-1 Pest Management Decision-Making Proposal

irrespective of whether options are screened and selected on the basis of their ecological properties or for other attributes (Reichelderfer et al., 1984).

First, knowledge of the pest control user groups' perceptions helps to identify and define the real problems that need to be addressed in the development of programs. Second, knowledge of the user groups' resource base and the institutional framework within which the group operates—producers or those who advise them —prevents the conduct of research that might otherwise lead to the development of unfeasible or inappropriate technology. Third, the use of economic criteria to develop and refine pest control strategies helps to ensure that the end-product of the research is not only feasible and ecologically appropriate in this context but also preferable to the users' current approaches. Demonstrations of the relative economic advantages of various pest control

strategies influence users' decisions to adopt or implement a particular option. This is a critical point for farmers at the strategy adoption stage. Finally, the outcome of a selected option's implementation is determined by how well the action addressed the needs and objectives of the user, which is why there is a feedback loop in the schematic. Those needs and objectives, though, are based on economic, psychological, and sociological factors, not just the technical factors; thus the importance of the human in the EBPM calculus. A tremendous range of pest management decision models has been developed and used specifically for the design of pest management systems that merge social with ecological considerations (Carlson and Wetzstein, 1993).

Economics plays another important role by providing a way of measuring trade-offs across species, across environmental media, and among the different functions of the ecosystem. Altieri and Nicholls (2000) discussed ecological trade-offs in agricultural ecosystems, urging that these be taken into account in pest management decision making. But there are really only a couple of currencies that can be used to measure ecological trade-offs in a consistent manner across environmental media. One is energy; and the other is money or monetary equivalents. Because pest management is anthropocentric, money seems to act as the more reasonable metric in making decisions about trade-offs. Economic theory, which allows monetary values to incorporate the dimensions of time and space, is critical for valuing or comparing the values of outcomes.

AT WHAT STAGES IS ECONOMICS USEFUL?

First, in the planning stage, when biological science partners are describing pest status, species identification, and distribution, and the ecological relationships that define an agroecosystem, economists can usefully survey the pest control market and identify the institutional factors that may improve the success of different ecologically based approaches. Second, the experimental phase is a particularly important point for economic input as approaches are being developed and tested in the laboratory or the field. If economists are not involved at this point, it is quite likely that the experiment will be designed in such a manner that the economic measures needed for assessing the EBPM system's economic feasibility cannot be attached to the outcomes of the experiment. This is a critical stage for interdisciplinary interaction.

Finally, in the implementation of pest management strategies, the identification of the constraints to adoption and the incentives for adoption are peculiarly intertwined with economics, psychology, sociology, and the health sciences. Here, then, the social sciences continue to play an important role in predicating the practical, on-the-ground success of ecologically successful pest management systems.

WHAT ARE THE BARRIERS TO INCORPORATING ECONOMICS IN INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH AND EXTENSION?

The alleged barriers to interdisciplinary research are notorious. A standard concern is that technical language and terminology are constraints among scientists.1 An equally weak claim is that scientists must oversimplify their own disciplinary approach for the sake of those in other fields, and that they cannot publish interdisciplinary research results in a disciplinary journal. In the context of EBPM research, this notion is conceptually absurd. EBPM researchers are dealing with problems that should be as attractive to intradisciplinary journals as they are to interdisciplinary ones. Empirical dismissal of commonly cited barriers is provided by Young (1995), whose study of a survey of agricultural economists who co-authored multidisciplinary research articles suggests that interdisciplinary research does not hinder one's professional status and, in fact, can be professionally rewarding.

This is not to say that there are no institutional barriers inhibiting interdisciplinary research. Disciplinary chauvinism is built into academe in a variety of ways (Duffy et al., 1997). Furthermore, the additional time requirements for interdisciplinary research do constitute a potential barrier to some untenured scientists who need to devote their time to research that will promote tenure. These problems may be exacerbated by academic institutions that have set time frames and predetermined levels of research productivity and types of research outlets for the consideration of tenure.

Perhaps the most serious barrier, however, is the lack of funding mechanisms for interdisciplinary works. The major competitive granting system for agriculture in this country is the USDA's National Research Initiative Competitive Grants program, which remains organized on basically disciplinary lines, despite the fact that there is encouragement and an honest attempt for interdisciplinary work (National Research Council, 1994). The peer panels in this granting program tend to be comprised solely of experts from a specific (though possibly broad) discipline—for example, the plant science panel would be comprised of plant scientists, the animal science panel by animal scientists, and so forth. It is often very difficult for a group of peers of a single discipline to judge the suitability of interdisciplinary studies while simultaneously considering other proposals that focus exclusively within the discipline. In this setting, interdisciplinary studies are at a disadvantage and face a greater funding barrier (Chubin and Hackett, 1990). If the process of peer review of proposals truly targets interdisciplinary work and money is truly provided for these types of proposals, then we can overcome those barriers quite rapidly.

|

1 |

It seems fair to assume that if plain English cannot be used by scientists to describe technical relationships, then either (a) the technical relationships are not understood well enough to be effectively communicated to people in other disciplines or (b) the non-communicating scientist is choosing to be pretentious and insular in his/her decision to continue using jargon. |

WHAT IMPACT DO PROFESSIONAL SOCIETIES HAVE WITH REGARD TO MONETARY INCENTIVES?

Most professional societies devote a considerable amount of time and energy to lobby—to secure and maintain specific sources of money from congressional granting—for very specific endeavors within their disciplines. The competitive nature of this activity is a much more severe constraint than is disciplinary culture, and can only be overcome by those societies agreeing to discontinue this type of lobbying behavior. Under the current conditions, there is little incentive for the societies to do that. There are coalitions and umbrella organizations whose missions are to increase funding for agricultural science without looking at it in a disciplinary perspective. Yet, the disciplinary lobbying continues and is something that professional societies should try to overcome in order to spur more funding for interdisciplinary research and study.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF INDUSTRY?

Industry and other components of the private sector are funding and pursuing a greater proportion of total agricultural research and development in this country than at any previous time. This is occurring at an increasing rate and is overtaking the public sector in the amount of resources devoted to agricultural research and development (Fuglie et al., 1996). Industry does not face the same barriers to interdisciplinary cooperation that are seen in the public sector. Most businesses are organized around their marketing, basic science, and applied science divisions. With this construct, businesses are often able to create an environment where interdisciplinary work is done to produce a product.

However, due in part to intellectual property issues, scientists in the public sector may be denied access to much of the knowledge that is created in that more goal-oriented, interdisciplinary-prone process. Thus, it is important to consider the private sector at the same time that we are thinking about the roles of professional societies and the public sector in furthering the needed interdisciplinary approaches in pest management research and extension. Indeed, the impact of public research funding and related policies on private sector incentives, and the subsequent need for public sector compensation to assure public goods provision (such as EBPM), is a much needed area of future research (Falck-Zepeda and Traxler, 2000).

REFERENCES

Altieri, M., and C.I. Nicholls. 2000. Applying agroecological concepts to the development of ecologically based pest management strategies. Paper presented at the National Research Council Professional Societies and Ecologically Based Pest Management workshop, March 10, 1999 in Raleigh, NC.

Carlson, G.A., and M.E. Wetzstein. 1993. Pesticides and pest management. Pp. 268–318 in Agricultural and Environmental Resource Economics, G.A. Carlson, D. Zilberman, and J.A. Miranowski, eds. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chubin, D.E., and E.J. Hackett. 1990. Peerless Science: Peer Review and US Science Policy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Duffy, P.A., E.A. Guertal, and R.B. Muntifering. 1997. The pleasures and pitfalls of interdisciplinary research in agriculture . Journal of Agribusiness 15(2):139–159.

Falck-Zepeda, J., and G. Traxler. 2000. The role of federal, state, and private institutions in seed technology generation. In Public–Private Collaboration in Agricultural Research, K.O. Fuglie and D.E. Schimmelpfennig, eds. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press.

Fuglie, K., N. Ballenger, K. Day, C. Klotz, M. Ollinger, J. Reilly, U. Vasavada, and J. Yee. 1996. Agricultural Research and Development: Public and Private Investments under Alternative Markets and Institutions. Agricultural Economic Report No. 735. Washington, DC: Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

National Research Council. ( 1994). Investing in the National Research Initiative. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Reichelderfer, K.H., G.A. Carlson, and G.A. Norton. 1984. Economic Guidelines for Crop Pest Control. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Young, D.L. 1995. Agricultural economics and multidisciplinary research. Review of Agricultural Economics 17(2):119–129.