6

Ripeness: The Hurting Stalemate and Beyond

I.William Zartman

There are essentially two approaches to the study and practice of negotiation (and its facilitated form, mediation).1 One, of longest standing, holds that the key to a successful resolution of conflict lies in the substance of the proposals for a solution. Parties resolve their conflict by finding an acceptable agreement—more or less a midpoint— between their positions, either along a flat front through compromise or, as more recent studies have highlighted, along a front made convex through the search for positive-sum solutions or encompassing formulas (Walton and McKersie, 1965; Young, 1975; Pruitt, 1981; Zartman and Berman, 1982; Raiffa, 1982; Pillar, 1983; Lax and Sebenius, 1986; Fisher and Ury, 1991; Pruitt and Carnevale, 1993; Hopmann, 1997).

The other holds that the key to successful conflict resolution lies in the timing of efforts for resolution. Parties resolve their conflict only when they are ready to do so—when alternative, usually unilateral, means of achieving a satisfactory result are blocked and the parties find themselves in an uncomfortable and costly predicament.2 At that point they grab on to proposals that usually have been in the air for a long time and that only now appear attractive.

It is obvious that the second school does not claim to have the sole answer (since it refers to the first) but rather maintains that substantive answers are fruitless until the moment is ripe. The same tends not to be true of the first school, which has long ignored the element of timing and has focused exclusively on finding the right solution regardless of the right moment. To be sure, attention to the question of timing does not obviate the analysis of substance, and in particular it does not guarantee

successful results once negotiation has begun. But more attention is needed to the timing question precisely because the analysis of substance has ignored it.

This chapter presents the state of current understanding of the most specific aspect of timing and the initiation of negotiations—the theory of “ripeness.” Because the metaphor of ripeness is easy to comprehend, the idea has resonated with practitioners. However, the apparent simplicity of the notion has also led to some confusion and misunderstanding among those who have written about it. To improve and advance understanding of the role of timing in the initiation of negotiations, it is necessary to make the implications of ripeness theory clearer.

To do so, this chapter begins with the presentation of the theory indicating necessary, even if not sufficient, elements in beginning negotiations and implications of the theory for both analysis and practice. It then discusses the experience and testimony of practitioners who have used the concept in their negotiations and mediation. Next it presents and evaluates refinements to the theory, followed by two types of remaining problems: the inherent, persistent resistance to the perception of ripeness and the tantalizing “other side of the moon” with its prospects for negotiation. In the process it carries the theory to its next extension, dealing with the continuation of negotiations toward a successful conclusion. Finally, the chapter addresses implications for practitioners in the absence of ripeness, specifically on the need and policies for ripening. As the argument proceeds, each discussion is summarized by definitional or hypothetical propositions.

RIPENESS THEORY IN PRACTICE

The notion of ripeness is critical for policy makers in the post-Cold War era who seek to mediate disputes in the international arena. It is also highly relevant for conflicting parties themselves as they assess their courses of action. Several aspects of the timing question need to be anchored in theory and practice. First, the concept and theory of ripeness need clarification, indicating what they do and do not cover. Second, the ways of recognizing ripeness need to be identified. Third, new questions raised by the concept and theory need to be addressed, so that further use and development can be accomplished.

The idea of a ripe moment lies at the fingertips of diplomats. “Ripeness of time is one of the absolute essences of diplomacy,” wrote John Campbell (1976:73). “You have to do the right thing at the right time.” “The success of negotiations is attributable not to a particular procedure chosen but to the readiness of the parties to exploit opportunities, confront hard choices, and make fair and mutual concessions,” wrote then

Secretary of State George Shultz (1988), without indicating specific moments. Few diplomats have tried to identify what it is that provides that essence or readiness, leaving its identification to a sense of feel. Henry Kissinger (1974) did better, recognizing that “stalemate is the most propitious condition for settlement.”

Conversely, practitioners are often heard to say that certain policies, including mediation initiatives, should not be pursued because the conflict just is not yet ripe. In mid-1992, in the midst of ongoing conflict, the Iranian deputy foreign minister noted that “the situation in Azerbaijan is not ripe for such moves for mediation” (Agence France Presse, May 17, 1992). Indeed, the notion comes out of the lexicon of practitioners, used with significant effect but only implicit content, and has only recently been taken up by analysts in an effort to make its meaning more explicit. These views can be summarized in a proposition: Proposition 1. Ripeness is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the initiation of negotiations, bilateral or mediated.

Even before turning to a detailed examination of the meaning and dynamics of ripeness, it is important to understand its strength and its limitations. Ripeness is only a condition: it is not self-fulfilling or self-implementing. It must be seized, either directly by the parties or, if not, through the persuasion of a mediator. Not all ripe moments are so seized and turned into negotiations, hence the importance of specifying the meaning and evidence of ripeness so as to indicate when conflicting or third parties can fruitfully initiate negotiations.

At the outset, confusion may arise from the fact that not all “negotiations” appear to be the result of a ripe moment. Negotiation may be a tactical interlude, a breather for rest and rearmamant, a sop to external pressure, without any intent of opening a sincere search for a joint outcome—thus the need for quotation marks or for some elusive modifier such as “serious” or “sincere” negotiations. It is difficult at the outset to determine whether negotiations are indeed serious or sincere, and indeed “true” and “false” motives may be indistinguishably mixed in the minds of the actors themselves at the beginning. Yet it is the outset that is the subject of the theory. The best that can be done is to note that many theories contain a reference to a “false” event or an event in appearance only, to distinguish it from an event that has a defined purpose. Indeed, a sense of ripeness may be required to turn negotiations for side effects (Ikle, 1964) into negotiations to resolve conflict. In any case, unless the moment is ripe, as defined below, the search for an agreed outcome cannot begin.

It therefore follows that ripeness is not identical to its results, which are not part of its definition, and is therefore not tautological. It has its own identifying characteristics that can be found through research independent of the possible subsequent resolution or of efforts toward it. It

also follows that ripeness theory is not predictive in the sense that it can tell when a ripe moment will appear in a given situation. It is predictive, however, in identifying the elements necessary (even if not sufficient) for the productive inauguration of negotiations. This type of analytical prediction is the best that can be obtained in social science, where stronger predictions could only be ventured by eliminating free choice (including the human possibility of blindness and mistakes). As such it is of great prescriptive value to policy makers seeking to know when and how to begin a peace process—and that is no small beer.

Components of Ripeness

Ripeness theory is intended to explain why, and therefore when, parties to a conflict are susceptible to their own or others’ efforts to turn the conflict toward resolution through negotiation. The concept of a ripe moment centers on the parties’ perception of a mutually hurting stalemate (MHS), optimally associated with an impending, past, or recently avoided catastrophe (Zartman and Berman, 1982; Zartman, 1983, 1985/ 1989; Touval and Zartman, 1985). The idea behind the concept is that, when the parties find themselves locked in a conflict from which they cannot escalate to victory and this deadlock is painful to both of them (although not necessarily in equal degrees or for the same reasons), they seek a way out. The catastrophe provides a deadline or a lesson indicating that pain can be sharply increased if something is not done about it now; catastrophe is a useful extension of the notion of an MHS but is not necessary to either its definition or its existence. In different images the stalemate has been termed the plateau, a flat and unending terrain without relief, and the catastrophe the precipice, the point where things suddenly and predictably get worse. If the notion of mutual blockage is too static to be realistic, the concept may be stated dynamically as a moment when the upper hand slips and the lower hand rises, both parties moving toward equality, with both movements carrying pain for the parties.3

The other element necessary for a ripe moment is less complex and controversial: the perception of a way out. Parties do not have to be able to identify a specific solution, only a sense that a negotiated solution is possible for the searching and that the other party shares that sense and the willingness to search too. Without the sense of a way out, the push associated with the MHS would leave the parties with nowhere to go. These elements can be combined in a definitional proposition: Proposition 2 (Definitional): If the (two) parties to a conflict (a) perceive themselves to be in a hurting stalemate and (b) perceive the possibility of a negotiated solution

(a way out), the conflict is ripe for resolution (i.e., for negotiations toward resolution to begin).

The basic reasoning underlying the MHS lies in cost-benefit analysis, based on the assumption that, when parties to a conflict find themselves on a pain-producing path, they prepare to look for an alternative that is more advantageous. This calculation is fully consistent with public choice notions of rationality (Sen, 1970; Arrow, 1963; Olson, 1965) and public choice studies of negotiation (Brams, 1990, 1994; Brams and Taylor, 1996), which assume that a party will pick the alternative it prefers and that a decision to change is induced by means of increasing pain associated with the present (conflictual) course. In game theoretical terms it marks the transformation of the situation in the parties’ perception from a prisoners’ dilemma into a chicken dilemma game (Brams, 1985; Goldstein, 1998). It is also consistent with prospect theory, currently in focus in international relations, which indicates that people tend to be more risk averse concerning gains than losses of equal magnitude and therefore that sunk costs or investments in conflict escalation tend to push parties into costly deadlocks or MHSs (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979; Bazerman et al., 1985; Stein and Pauly, 1992; Mitchell, 1995).

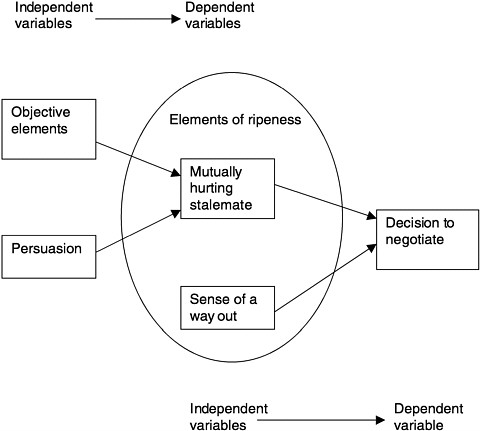

The ripe moment is necessarily a perceptual event, not one that stands alone in objective reality; it can be created if outside parties can cultivate the perception of a painful present versus a preferable alternative and therefore can be resisted so long as the party in question refuses or is otherwise able to block out that perception. As with any other subjective perception, there are likely to be objective referents or bases to be perceived. These can be highlighted by a mediator or an opposing party when they are not immediately recognized by the parties themselves, but it is the perception of the objective condition, not the condition itself, that makes for an MHS. Since such a stalemate is a future or contingent event, referring to the impossibility of breaking out of the impasse—“It can’t go on like this”—any objective evidence is always subject to the recognition of the parties before it becomes operative. If the parties do not recognize “clear evidence” (in someone else’s view) that they are in an impasse, an MHS has not (yet) occurred, and if they do perceive themselves to be in such a situation, no matter how flimsy the “evidence,” the MHS is present. The relationship between objective and subjective components can be summarized in a proposition: Proposition 3: An MHS contains objective and subjective elements, of which only the latter are necessary and sufficient to its existence. The first three propositions can be combined into a model expressing a theory of ripeness in which ripeness is located as both a dependent and an independent variable (see Figure 6.1).

FIGURE 6.1 Factors affecting ripeness, elements of ripeness, and the decision to negotiate.

Identifying the Components

Since an MHS is a subjective matter, it can be perceived at any point in the conflict, early or late. Nothing in the definition of an MHS requires it to take place at the height of the conflict or at a high level of violence. The internal (and unmediated) negotiations in South Africa between 1990 and 1994 stand out as a striking case of negotiations opened (and pursued) on the basis of an MHS perceived by both sides on the basis of impending catastrophe, not of present casualties (Ohlson and Stedman, 1994; Sisk, 1995; Zartman, 1995b; Lieberfield, 1999a, 1999b). However, the greater the objective evidence, the greater the subjective perception of a stalemate and its pain is likely to be, and this evidence is more likely to come late, when all other courses of action and possibilities of escalation have been exhausted. In notable cases a long period of conflict is required

before the MHS sinks in, whereas few if any studies have been made of early settlements and the role of long-range calculations. Indeed, given the infinite number of potential conflicts that have not reached the “heights,” evidence would suggest that perception of an MHS occurs either at a low level of conflict, where it is relatively easy to begin problem solving in most cases, or in salient cases at rather high levels of conflict, a distinction that could be the subject of broad research. While the optimum situation would arguably be the first, where the parties to a conflict perceive ripeness before much escalation and loss of life have occurred, there is as yet little evidence—but a lot of methodological problems—in this regard, and such wisdom would still leave unanswered the question of how the importance of an issue would be established. In any case, as suggested, conflicts not treated “early” appear to require a high level of intensity for an MHS perception to kick in and negotiations toward a solution to begin.

As the notion of ripeness implies, an MHS can be a very fleeting opportunity, a moment to be seized lest it pass, or it can be of a long duration, waiting to be noticed and acted on by mediators. In the citations below the moment was brief in Bosnia but longer in Angola. In fact, failure to seize the moment often hastens its passing, as parties lose faith in the possibility of a negotiated way out or regain hope in the possibility of unilateral escalation. By the same token, the possibility of long duration often dulls the urgency of rapid seizure. Behind the duration of the ripe moment itself is the process of producing it through escalation and decision. The impact of incremental compared with massive escalation (Mitchell, 1995; Zartman and Aurik, 1991), and the internal process of converting members impervious to pain (hawks) into “pain perceivers” (doves) (Stedman, 1997; Mitchell, 1995) are further examples of research questions opened by the concept of ripeness.

The other component of a ripe moment—a perception by both parties of a way out—is less difficult to identify. Leaders often indicate whether they do or do not feel that a deal can be made with the other side, particularly when there is a change in that judgment. The sense that the other party is ready and willing to repay concessions with concessions is termed requitement (Zartman and Aurik, 1991). This element is also necessary (but, alone, insufficient) since, without a sense of the possibility of a negotiated exit from an MHS, fruitful negotiations cannot take off. Conversely, cases abound in which the absence of this component prevented otherwise promising beginnings to a negotiation. These elements of evidence and indication can be summarized in a proposition: Proposition 4: If the parties’ subjective expressions of pain, impass, and inability to bear the costs of further escalation, related to objective evidence of stalemate, data on numbers and nature of casualties and material

costs, and/or other such indicators of an MHS can be found, along with expressions of a sense of a way out, ripeness exists.

Research and intelligence on ripeness are needed to ascertain whether its defining components exist at any time and whether it is or can be seized by the parties or mediator(s) in order to begin negotiations. Thereafter, further research questions are needed to find out whether that moment can be prolonged or whether its favorable predispositions can be transferred to the process of negotiation itself (Mooradian and Druckman, 1999). Researchers would look for evidence, for example, whether the rapidly shifting military balance in the Burundian civil war has given rise to a perception of an MHS by the parties, as well as a sense by authoritative spokesmen for each side that the other is ready to seek a solution to the conflict, or, to the contrary, whether it has reinforced the conclusion that any mediation is bound to fail because one or both parties believes in the possibility or necessity of escalating out of the current impasse to achieve a decisive military victory. Research and intelligence would be required to learn why Bosnia in the war-torn summer of 1994 was not ripe for a negotiated settlement and mediation would fail and why it was ripe in November 1995 and mediation could use that condition to achieve agreement (Touval, 1996; Goodby, 1996). Similarly, research would indicate that there was no chance of mediating a settlement in the Ethiopia-Eritrean conflict in the early 1980s and early 1990s, or in the Southern Sudan conflict in the early 1990s, the skills of President Carter notwithstanding, because the components of ripeness were not present (Ottaway, 1995; Deng, 1995). The relationship of mediator tactics to ripeness can be summarized in a proposition: Proposition 5: (a) Once ripeness has been established, specific tactics by mediators can seize the ripe moment and turn it into negotiations; (b) If only objective elements of ripeness exist, specific tactics by mediators can bring the conflicting parties to feel/understand the pain of their mutual stalemate and turn to negotiations.

RIPENESS IN ACTION

While ripeness has not always been used to open negotiations, there have been occasions when it has come into play, as identified by both analysts and practitioners. A number of studies beyond the original examination (Zartman and Berman, 1982; Zartman, 1983, 1985/1989, 1986; Touval and Zartman, 1985; Zartman and Aurik, 1991) have used and tested the notion of ripeness regarding negotiations in Zimbabwe, Namibia and Angola, Eritrea, South Africa, Philippines, Cyprus, Iran-Iraq, Israel, Mozambique, and elsewhere (Touval, 1982; Haass, 1990; Stedman, 1991; Kriesberg and Thorson, 1991; Sisk, 1995; Druckman and Green, 1995; Zartman, 1995a; Norlen, 1995; Hampson, 1996; Goodby, 1996; Taisier and

Matthews, 1999; Salla, 1997; Pruitt, 1997; Aggestam and Jönson, 1997; Mooradian and Druckman, 1999; Sambanis, in press). Touval’s (1982) work on the Middle East was particularly important in launching the idea. In general, these studies have found the concept applicable and useful as an explanation for the successful initiation of negotiations or their failure, while in some cases proposing refinements to the concept.

Other diplomatic memoirs have specifically referred to the idea by its MHS component. Chester Crocker, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Africa between 1981 and 1989, patiently mediated an agreement between Angola and South Africa for the withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola and of South African troops from Namibia, then to become independent. For years an MHS, and hence an agreement, eluded the parties. “The second half of 1987 was the great turning point…. This was the moment when the situation ‘ripened’” (Crocker, 1992:363). Military escalations on both sides in southern Angola heightened the conflict and the chances for further military damage; “a battle of perceptions was underway” (p. 370). Bloody confrontations in southeastern Angola beginning in November 1987 and in southwestern Angola in May 1988 ended in a draw. “By late June 1988, the cycle of South African and Cuban military moves in 1987– 88 was nearly complete. The Techipa-Calueque clashes in southwestern Angola confirmed a precarious military stalemate. That stalemate was both the reflection and the cause of underlying political decisions. By early May, my colleagues and I convened representatives of Angola, Cuba, and South Africa in London for face-to-face, tripartite talks. The political decisions leading to the London meeting formed a distinct sequence, paralleling military events on the ground, like planets moving one by one into a certain alignment” (Crocker, 1992:373).

In his conclusion, Crocker identifies specific signs of ripeness while qualifying that “correct timing is a matter of feel and instinct” (p. 481). He details the maintenance of the status quo at Cuito Carnevale despite massive Cubans reinforcements at the end of 1987, which led to a change from a “climate [that] was not conducive” in December to a meeting at the end of January when “negotiation was about to change for good” (pp. 373– 374). The American mediation involved building diplomatic moves that paralleled the growing awareness of the parties, observed by the mediator, of the hurting stalemate in which they found themselves.

At the United Nations, Assistant Secretary General for Political Affairs Alvaro de Soto also endorsed the necessity of ripeness in his mission to mediate a peace in El Salvador. After chronicling a series of failed initiatives, he pointed to the importance of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front’s (FMLN) November 1989 offensive, the largest of the war, which penetrated the main cities, including the capital, but failed to dislodge the government.

The silver lining was that it was, almost literally, a defining moment— the point at which it became possible to seriously envisage a negotiation. The FMLN had been reviewing their long-term prospects and strategy since 1988, adjusting their sights in the process. They were coming to the view that time was not entirely on their side…. [T]he offensive showed the FMLN that they could not spark a popular uprising…. The offensive also showed the rightist elements in government, and elites in general, that the armed forces could not defend them, let alone crush the insurgents…. However inchoate at first, the elements of a military deadlock began to appear. Neither side could defeat the other. As the dust settled, the notion that the conflict could not be solved by military means, and that its persistence was causing pain that could no longer be endured, began to take shape. The offensive codified the existence of a mutually hurting stalemate. The conflict was ripe for a negotiated solution, (de Soto, 1999:356)

In his parting report, Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations Marrack Goulding (1997:20) specifically cited the literature on ripeness in discussing the selection of conflicts to be handled by an overburdened UN: “Not all conflicts are ‘ripe’ for action by the United Nations (or any other third party)…. It therefore behooves the Secretary-General to be selective and to recommend action only in situations where he judges that the investment of scarce resources is likely to produce a good return (in terms of preventing, managing and resolving conflict).”

In Yugoslavia, Secretary of State James Baker looked for a ripe moment during his quick trip to Belgrade in June 1991 and reported the same day to President George Bush that he did not find it: “My gut feeling is that we won’t produce a serious dialogue on the future of Yugoslavia until all the parties have a greater sense of urgency and danger” (Holbrooke, 1998). Holbrooke calls this “a crucial misreading,” as he did the later moment created by the Croatian Krajina offensive in August 1995. Holbrooke had his own image of the MHS (or the upper hand slipping and the underdog rising): “The best time to hit a serve is when the ball is suspended in the air, neither rising nor falling. We felt this equilibrium had arrived, or was about to, on the battlefield [in October 1995].” Trying to instill in Bosnian President Izetbegovic a perception, Holbrooke and his team pointed out “that the [Croat-Bosniac] Federation had probably reached its point of maximum conquest…. [I]n all wars, there were times for advance and times for consolidation, and in our opinion this was a time for consolidation [through negotiation]…. ‘If you continue the war, you will be shooting craps with your nation’s destiny’” (Holbrooke, 1998:193). It took the Croatian offensive, coupled with NATO bombing, to create an MHS composed of a temporary Serb setback and a temporary Croat advance that could not be sustained. As a State Depart-

ment official stated: “Events on the ground have made it propitious to try again to get the negotiations started. The Serbs are on the run a bit. That won’t last forever. So we are taking the obvious major step” (New York Times, August 9, 1995, p. A7). Many other statements by practitioners could be cited. In brief, alert practitioners do not seem to have difficulty identifying the existence or importance of an MHS for the opening of negotiations, although not all practitioners are so alert.

PROPOSED REFINEMENTS TO THE THEORY

The notion of ripeness is a simple idea that has been born out in a number of studies but that has also been subject to frequent, sometimes curious, misunderstandings. Many of these should be able to be eliminated by careful attention to the concept, while others have suggested further study and refinement.

The most important refinements carry the theory to a second level of questions about the effects of each side’s pluralized politics on both the perceptions and the uses of ripeness. What kinds of internal political conditions are helpful both for perceiving ripeness and for turning that perception into the initiation of promising negotiations? A careful case study by Stedman (1991) of the Rhodesian negotiations for independence as Zimbabwe takes the concept beyond a single perception into the complexities of internal dynamics. Stedman specifies that some but not all parties must perceive a hurting stalemate, that patrons rather than parties may be the agents of perception, that the military element in each party is the crucial element in perceiving the stalemate, and that the way out is as important an ingredient as the stalemate in that all parties may well see victory in the alternative outcome prepared by negotiation (although some parties will be proven wrong in that perception). Stedman also highlights the potential of leadership change for the subjective perception of an MHS where it had not been seen previously in the same objective circumstances and of the threat of domestic rivals to incumbent leadership, rather than threats from the enemy, as the source of impending catastrophe, points also applied by Lieberfield (1999a, 1999b) in his more recent comparison of the Middle East and South Africa.

The original formulation of the theory added a third element to the definition of ripeness—the presence of a valid spokesman for each side; it has been dropped in the current reformulation because as a structural element it is of a different order than the other two defining perceptual elements. Nonetheless, it remains of second-level importance, as Stedman and Lieberfield point out. The presence of strong leadership recognized as representative of each party and that can deliver that party’s compliance to the agreement is a necessary (while alone an insufficient) condi-

tion for productive negotiations to begin or, indeed, end successfully. The discussion of leadership conditions for ripeness to be perceived and used illustrates not only a fruitful area for further research but also the way in which the basic concept can give rise to ancillary questions of importance that build on the original theory.

Other studies have used and discussed the notion of ripeness in a search for alternatives and restatements, although the result has generally been a reaffirmation of the concept. Kriesberg and Thorson (1991), particularly in the chapters by Hurwitz and Rubin, emphasize the elusiveness and perceptional quality of the concept and its possible misuse as an excuse for inaction. Haass (1990) restates the components of ripeness as time pressure, appropriate power relations, acceptable formula (way out), and acceptable process, emphasizing in the rest of his work the elusiveness of the moment and the need to prepare or position for it in its absence. The latter discussion of alternative policies in the absence of ripeness is a useful extension, although in the attempt to restate the concept, it loses its precision and its distinction from resolution. A number of commentators (Licklider, 1995; Walter, 1997; Kleiboer, 1994, 1997; Kleiboer and ‘t Hart, 1995) allege tautology in the concept, confusing ripeness with final results. Kleiboer proposes instead the notion of willingness, which in fact repeats the perceptional aspect of ripeness without the causal component of the MHS.

There have been a number of attempts to reformulate the concept of ripeness. Druckman and Green (1995:299) have defined ripeness as the intersection of an insurgency’s “calculation that its effective power was increasing while its legitimacy remained constant, and a government calculation that its power was decreasing while its legitimacy remained unchanged.” The discussion reaffirms many aspects of MHS—its perceptional (calculated) quality, its objective base, its bilateral character, its initiating reference, and its researchable nature—but it adds the element of legitimacy, not only constant but high. Indeed, the stalemate is to be found on the level of legitimacy in this reformulation in addition to the more dynamically evolving stalemate on the level of power. More testing is needed of this additional element.

Goodby (1996) has defined ripeness entirely differently, focusing on the susceptibility of the situation to change through external (mediator’s) inputs. Seeking to distinguish ripe moments from other stalemates, even mutually hurting ones, that “the parties to the conflict may be able to live with,” Goodby (1996:502) draws on catastrophe theory (Forrester, 1961; Sandefur, 1990; Nicholson, 1989; Lachow, 1993) to distinguish between nonlinear stable, unstable, and metastable situations, the third—when “small external inputs can have large effects on the system”—being ripe for negotiation. From the perception of a third party, if small external

efforts can accomplish major changes, the situation is ripe for resolution (i.e., for the third party to assist negotiations toward resolution). Firm indicators for metastability remain to be developed.

Pruitt (1997) and Pruitt and Olczak (1995) have extended the notion of ripeness into the negotiations themselves under the name of “readiness theory.” Pruitt starts with the elements that ripeness theory seeks to explain (i.e., motivation to cooperate and requitement toward a way out) and posits them as push and pull factors driving negotiation to its conclusion. In identifying the sources of the first, which he terms motivational ripeness (presumably as opposed to objective referents to ripeness), he adds the positive factor of mutual dependence in achieving the goal to the negative elements already contained in the MHS (unattainable victory, unacceptable costs in escalation). Motivational ripeness is the parties’ “willingness to give up a lot now in exchange for substantial concessions from the other rather than waiting [until] later in the hope that the other can be persuaded to make these concessions unilaterally.” Like the original formulation, Pruitt’s discussion also underlines the point that parties can come to this willingness/perception for different reasons, at different speeds, and even at different times, as well as the need for both parties to sense that there is a way out (and hence to sense that the other party so senses). The need for—presumably perceived—mutual dependence as an element in ripeness has not been tested beyond the initial proposal and could be done so fruitfully.

Spector (1998) has also written of “readiness,” in a different sense, referring to negotiators’ and mediators’ capacity to negotiate, which is necessary even when ripeness is present. Skill and resources, including identity, interests, and strategies, are necessary components without which the parties are unlikely to be able to seize the ripe moment. Additional studies (Crocker et al., 1999; Maundi et al., 2000) have developed this notion.

Such discussions miss some of the original points and emphasize others in an effort to better grasp the essence of ripeness theory. The value of these efforts is highlighted by the question: Are they formulating a different concept, adding new terms or precision to the old original concept, or expressing the concept itself in different terms? For the most part it would seem that the emendations have either helped refine aspects of the concept or expressed the same thing differently, rather than offering an alternative concept or theory.

Some of the commentary on ripeness theory raises the relationship between parsimony in theory building and complexity in human action. This is a problem that dogs any attempt at social science theorizing and, carried to its extreme, is merely a matter of two different levels of discourse and analysis that can never meet. However, the present formulation of ripeness theory has sought to leave room for other undeniably

important aspects of mediation and negotiation by referring to necessary but not sufficient components of ripeness. Other elements do play a role, often of varying importance. One has been identified from the outset: the substantive search for a formula for agreement between the parties. Another of particular importance is the authoritative structure of each side, most notably the presence of a valid spokesman who can represent a party and deliver its concurrence and compliance as negotiations proceed. Others could be added, and the effort to advance a clear and unambiguous theory, which is necessary to testing and application, in no way eliminates such facilitating variables.

Problems: Resistant Reactions

There are other intriguing problems raised by ripeness theory. One complication with the notion of a hurting stalemate arises when increased pain increases resistance rather than reducing it. Thus, under some conditions, an MHS does not create an opening for negotiation but makes it more difficult (it must be remembered that, while ripeness is a necessary precondition for negotiation, not all ripeness leads to negotiation.) Although this may be considered “bad,” irrational, or even adolescent behavior, it is a common reaction and one that may be natural and functional. The reinforcing reaction to hurt in a stalemate can be tied to four different levels of situations or contexts. First is the normal response to opposition: “Don’t give up without a fight,” and “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.” The imposition of pain to a present course in conflict is not likely to lead to a search for alternative measures without first being tested. The theory itself takes this into account by referring to the parties’ being locked into a stalemate from which they cannot escalate an exit, implying efforts to break out before giving in. Nonetheless, since the ripe moment is tied to perception, nothing indicates when and how the switch from breaking-out perceptions to giving-in perceptions will occur. In other words, while the theory indicates that an MHS is a necessary and identifiable element, nothing (other than tautological definitions) indicates when it will occur.

Second, while escalations are commonly taken to refer only to the means of conducting a conflict, they also refer to other aspects of conflict behavior, including ends and agents (Rubin et al., 1994). The latter is particularly relevant. Pressure on a party in conflict often leads to the psychological reaction of worsening the image of the opponent, a natural tendency that is often decried as lessening the chances of reconciliation but that has the functional feature of justifying resistance. Thus, the conditions that are designed to produce the ripe moment tend to produce its opposite, as a natural reaction.

Third, particular types of adversaries are especially prone to reinforcing behavior. Parties thinking as true believers are unlikely to be led to compromise by increased pain; instead, pain is likely to justify renewed struggle (Hoffer, 1951). Justified struggles call for greater sacrifices, which absorb increased pain. The cycle is functional and self-protecting. The first party increases its resistance as pressure and pain increase, so that pain strengthens determination. To this type of reaction it is the release of pain or an admission of pain on the other side that justifies relaxation; when the opponent admits the error of its ways, the true believer can claim the vindication of its efforts, which permits a management of the conflict (Moses, 1996).

The fourth level anchors the true believer in a particular culture. There are no independent nontautological characteristics available to identify cultures hospitable to true believers, and since the behavioral type and the general culture tend to coexist rather than one preceding the other, the predictive possibilities are slim. True-believer cultures are those hospitable to high commitment, either in escatalogical or ideological terms, where there are additional external rewards to hanging tough and where higher goals or values are thereby enhanced. There have been some attempts to relate such cultures to nonnegotiatory mindsets, as in Nicolson’s (1960) “warriors” and Snyder and Diesing’s (1977) hard-liners and irrational types, the former explicitly referring to Nazi Germany and the latter implicitly to Communists, among others.

In the current era, cases of resistant reactions to hurting stalemates come particularly from the Middle East, from Iran during the hostage negotiations (Moses, 1996) to Iraq during the second Gulf War. In the hostage negotiations the established wisdom is that negotiations were not possible as long as holding the hostages was worth more to Iran than releasing them and therefore not until the parliamentary election of 1980 (Christopher et al., 1985). However, new research and interpretations also show that negotiations were not possible as long as the United States was seen as exerting pressure on Iran, since pressure was seen as the opposite of contrition and an arrangement was not possible as long as the United States had not learned the lesson of its evil ways and turned from them. Thus, while the United States was operating under the logic of the hurting stalemate, Iran was following the logic of the justifying pain. Negotiations came when the two different “lines” crossed each other.

In the second Gulf War, even though neither side was interested in negotiation, the same class of logic obtained. The United States thought that increasing pressure and threat of catastrophe would bring Iraq to heel, but the higher the pressure the more justification it provided to Iraq to raise its threshold of resistance. If there were any chance of negotiation in the conflict, it was earlier rather than later (Jentleson, 1995); each turn

of pressure raised the level of acceptance correspondingly, rather than rising toward a constant threshold where the possibility of negotiation could be found. The very act of holding out against mounting pressure from the Great Satan was a religious and nationalistic act of heroism, itself worthy of being called a victory: lying down on the railroad tracks before the oncoming locomotive was a glorious gesture, highly meritorious in itself regardless of the consequences. It showed not only the high ideals and selflessness of the defender but also the inhumanity and ruthlessness of the opponent. Hurting stalemates in such cultures are meaningless, since breaking down and agreeing to negotiate are a denial of the very ideals that inspired the resistance in the first place. Of course, it takes two to make a mutually hurting stalemate, and American lack of interest in negotiation at any time can raise questions about the cultural approach.

In sum, there is a resistant reaction, which, whether stemming from perseverance, agent escalation, true belief, or ideological cultures, means that the mechanism of the hurting stalemate in certain conditions may be its own undoing. The more an MHS is sought, the more it may be resisted as a sign of a conflict unripe for resolution. Identifying the phenonenon is not always simple. Since part of the resistant reaction phenomenon is a normal response to pressure and since the hurting stalemate is a perceptual event, initial resistance is to be expected. A true-believer reaction and an ideological culture can generally be identified by their context and language. Probably most difficult to sort out is the agent escalation, since its very nature is to escalate to vilifying generalizations the reasons for opposing the adversary.

The remedy is less clear and certainly less straightforward. One could hardly advise: in cost-benefit cultures, create a hurting stalemate as a ripe moment; in true-believer cultures, exhibit contrition as a ripe moment. That is, however, what happened in the Pueblo incident between the United States and North Korea, an incident cited more frequently as an aberration than a model. In the two Gulf cases, the two American presidents’ strategies were diametrically opposite, but Carter’s success in negotiation may be more attributable to the additional factor of the change in value of the hostages than to any difference in approach to ripeness. At the same time, Carter continually held out negotiations as an option and finally succeeded, whereas Bush continually ruled out negotiations as an option (and he too succeeded, in his terms!). The ultimate lesson is probably no more startling than the notion of a ripe moment itself: negotiations with true believers take longer to come about because ripe moments are harder to find. But in the end, if time and patience are available, true believers (or their followers) must eat too, so that pain can be treated as a universal human feeling, with various antidotes and painkillers available to deaden or delay its effects.

Problems: Compelling Opportunities

The other drawback about the notion of a hurting stalemate is its dependence on conflict. Odd and banal as that may sound, its implications are sobering. It means, on the one hand, that preemptive conflict resolution and preventive diplomacy are unpromising, since ripeness is hard to achieve so far ahead. On the other hand, it means that to ripen a conflict one must raise the level of conflict until a stalemate is reached and then further until it begins to hurt—and even then work toward a perception of an impending catastrophe as well. The ripe moment becomes the godchild of brinkmanship.

At the same time, another limitation to the theory—seemingly unrelated to the above—is that it addresses only the opening of negotiations, as noted at the outset and often missed by the critics. Now that the theory of ripeness is available to explain the initiation of negotiation, people would like to see a theory that explains the successful conclusion of negotiations once opened. Can ripeness be extended in some way to cover the entire process, or does successful conclusion of negotiations require a different explanatory logic?

Practitioners and students of conflict management would like to think that there could be a more positive prelude to negotiation and can even point to a few cases of negotiations, mediated or direct, that opened or came to closure without the push of a mutually hurting stalemate but through the pull of an attractive outcome. Although examples are rare, as explained by prospect theory, one case is the opening of the Madrid peace process on the Middle East in 1992 (Baker and de Frank, 1995); another may be boundary disputes that are overcome by the prospects of mutual development in the region. But the mechanisms are still unclear in part because the cases are so few. As in other ripe moments these occasions provided an opportunity for improvement but from a tiring rather than a painful deadlock (Mitchell, 1995; Zartman, 1995a). In some views the attraction lies in a possibility of winning (paradoxically a shared perception) more cheaply than by conflict or else a possibility of sharing power that did not exist before (Mitchell, 1995). In other views, enticement comes in the form of a new ingredient, provided by a persistent mediator and more than simply an apparent way out, and that new ingredient is the chance for improved relations with the mediating third party (Touval and Zartman, 1985; Saunders, 1991). In other instances the opportunity for a settlement grows more attractive because the issue of the conflict becomes depassé, no longer justifying bad relations with the other party or the mediator that it imposed. Such openings might be termed mutually enticing opportunities (MEOs), admittedly a title not as catchy as MHS and a concept not as well researched (or practiced). Few examples have been found in reality.

But an MEO is important in the broader negotiation process and has its place in extending ripeness theory. As indicated, ripeness theory refers to the decision to negotiate; it does not guarantee any results. At most it can be extended into the negotiations themselves by indicating that the perception of ripeness must continue during negotiations if the parties are not to reevaluate their positions and drop out, in the revived hopes of being able to find a unilateral solution through escalation. But negotiations completed under the shadow—or the push—of an MHS alone are likely to be unstable and unlikely to lead to a more enduring settlement. A negative shadow can begin the process but cannot provide for the change of mentalities to reconciliation. As Ohlson (1998), Pruitt (1997), and Pruitt and Olczak (1995) have pointed out, that is the function of the MEO.

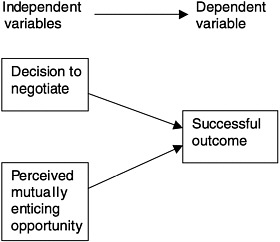

While an MHS is the necessary and insufficient condition for negotiations to begin, during the process the negotiators must provide the prospects for a more attractive future to pull them out of their conflict. The push factor has to be replaced by a pull factor, in the terms of a formula for settlement and prospects of reconciliation that the negotiating parties design during negotiations (see Figure 6.2). Here the substantive aspect of negotiation in analysis and practice pulls ahead of the procedural approach: the way out takes over from the hurting stalemate. The seeds of the pull factor begin with the way out that the parties vaguely perceive as part of the initial ripeness, but this general sense of possibility needs to be developed and fleshed out to be the vehicle for an agreement. When an MEO is not developed in the negotiations, the negotiations remain trun

FIGURE 6.2 Conditions for a successful outcome of negotiations.

cated and unstable, even if a conflict management agreement to suspend violence is reached, as in the 1984 Lusaka agreement or the 1994 Karabakh cease-fire (Zartman, 1985/1989; Mooradian and Druckman, 1999). At this point the substantive literature on negotiation referred to at the beginning finds its place, which can be shown in a proposition: Proposition 6: The perception of a mutually enticing opportunity is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the continuation of negotiations to the successful conclusion of a conflict.

Implications: Positioning and Ripening

Crocker (1992:471) states very forcefully (in boldface in the original) that “the absence of ‘ripeness’ does not tell us to walk away and do nothing. Rather, it helps us to identify obstacles and suggests ways of handling them and managing the problem until resolution becomes possible.” Crocker’s own experience indicates, first and above all, the importance of being present and available to the contestants while waiting for the moment to ripen so as to be able to seize it when it occurs. Thus, two policies are indicated when the moment is not ripe: positioning and ripening.

Strategies of positioning and ripening are adjuncts to ripeness theory, but they are very important to the practitioner. As such they are not theoretically tight but rather suggestive. To begin with, Crocker (1992; see also Haass, 1990, and Goulding, 1997) lists a number of important insights for positioning:

-

Give the parties some fresh ideas to shake them up.

-

Keep new ideas loose and flexible and avoid getting bogged down early in details.

-

Establish basic principles to form building blocks of a settlement.

-

Become an indispensable channel for negotiation.

-

Establish an acceptable mechanism for negotiation and an appropriate format for registering an agreement.

Other strategies include preliminary explorations of items identified with prenegotiations (Stein, 1994):

-

Identify the parties to be involved in the settlement.

-

Identify the issues to be resolved, and separate out issues that are not resolvable in the conflict.

-

Air alternatives to the current conflict course.

-

Establish bridges between the parties.

-

Clarify costs and risks involved in seeking a settlement.

-

Establish requitement, the sense that each party will reciprocate the other’s concessions.

-

Assure support for a settlement policy within each party’s domestic constituency.

Ripening can also be the subject of creative diplomacy. Since the theory (Proposition 3) indicates that ripeness results from objective indicators plus persuasion, these are the two elements that need attention in ripening. If some objective elements are present, persuasion is the obvious diplomatic element, serving to bring out the perception of both a stalemate and pain. Such was the message of Henry Kissinger in the Sinai withdrawal negotiations (Golan, 1976) and of Crocker in the Angolan negotiations (Crocker, 1992), among many others, emphasizing the absence of real alternatives (stalemate) and the high cost of the current conflict course (pain).

If there is no objective indicator to which to refer, ripening may involve a much more active engagement of the mediator, moving that role from communication and formulation to manipulation (Zartman and Touval, 1997; Touval, 1999; Rothchild, 1997). As a manipulator the mediator either increases the size of the stakes, attracting the parties to share in a pot that otherwise would have been too small, or limits the actions of the parties in conflict, providing objective elements for the stalemate. Such actions are delicate and dangerous since they threaten the neutrality and hence the usefulness of the mediator, but on occasion they may be deemed necessary. The NATO bombing of Serb positions in Bosnia in 1995 to create a hurting stalemate, or the American arming of Israel during the October war in 1973 or of Morocco (after two years of moratorium) in 1981 to keep those parties in the conflict, among many others, are typical examples of the mediator acting as a manipulator to bring about a stalemate. (Kissinger’s action to increase the size of the pot during the second Sinai disengagement through U.S. aid is an example of the first type of manipulation.)

Finally, using ripeness as the independent variable, practitioners need to use all of their skills and apply all concepts of negotiation and mediation to take advantage of that necessary but insufficient condition in order to turn it into a successful peace-making process. Here the various notions of “readiness” already indicated are useful but not exclusively so. The study and practice of negotiation are so complex that both analysts and practitioners should be on guard against any single-factor theory or approach.

CONCLUSION

The investigation into ripeness and the attempt to turn an intuitive notion into an analytical concept was undertaken with the aim of producing a useful tool for practitioners as well as analysts. Parsimony, explicitness, and precision are particularly important not only in developing common terms and meanings so that the object can be discussed and used (i.e., in specifying the intuitive) but also in bringing out hidden implications and refocusing inquiry on refinements and new areas uncovered by a precision of the concept (i.e., in uncovering the counterintuitive). If the limitations on a concept are bigger than the concept itself, one should start looking elsewhere. But limitations become particularly interesting when they open up the possibilities and alternatives for better analysis and better practice. It is in that hope that this presentation will open fruitful discussions and applications of the use of hurting stalemates and the creation of compelling opportunities.

There is room for further research all along the ripening process. More work needs to be done on ways in which unripe situations can be turned ripe by third parties so that negotiations and mediation can begin, and, of course, the mainstream of negotiation research on how to take advantage of ripe moments by bringing the parties to a mutually satisfactory agreement needs to be continued. The proposed refinements need operationalization and testing. The relationship between objective and subjective components of stalemate needs better understanding, as does ex ante measurement and evaluation of the ripening process, of the MHS itself, and of the escalation process leading to it (Mooradian and Druckman, 1999; Zartman and Aurik, 1991; Faure and Zartman, forthcoming). It would indeed be desirable if there were “another side to the moon,” that is, if an MEO could be theoretically developed and practically exploited as the other entry door to negotiation; most people engaged in the study and practice of negotiation would be pleased to see the MHS demoted to only one of two necessary (even if not sufficient) conditions for the initiation of negotiation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to Chester Crocker, Daniel Druckman, Alexander George, James Goodby, Timothy Sisk, Stephen Stedman, Paul Stern, and an unidentified reader for their input in preparing this paper.

NOTES

REFERENCES

Aggestam, Karin, and Jönson, Christer 1997 (Un)ending conflict. Millennium XXXVI(3):771–794.

Arrow, Kenneth 1963 Social Choice and Individual Values. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Baker, James, and de Frank, Thomas M. 1995 The Politics of Diplomacy. New York: Putnam.

Bazerman, Max, Magliozi, T., and Neale, M.A. 1985 The acquisition of an integrative response in a competitive market. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 34:294–313.

Brams, Steven J. 1985 Superpower Games: Applying Game Theory to Superpower Conflict. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

1990 Negotiation Games. New York: Routledge.

1994 Theory of Moves. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brams, Steven J., and Taylor, Alan D. 1996 Fair Division. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Burton, Michael, and Higley, John 1987 Elite settlements. American Sociological Review LII(2):295–307.

Campbell, John 1976 Successful Negotiation: Trieste. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Christopher, Warren, et al. 1985 American Hostages in Iran. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Crocker, Chester A. 1992 High Noon in Southern Africa. New York: Norton.

Crocker, Chester A., Hampson, Fen Osler, and Aall, Pamela, eds. 1999 Herding Cats: The Management of Complex International Mediation. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace.

Deng, Francis 1995 Negotiating a hidden agenda: Sudan’s conflict of identities. In Elusive Peace: Negotiating an End to Civil Wars, I.William Zartman, ed. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution,

de Soto, Alvaro 1999 Multiparty mediation: El Salvador. In Herding Cats: The Management of Complex International Mediation, Chester Crocker, Fen Osler Hampson, and Pamela Aall, eds. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace.

Druckman, Daniel, and Green, Justin 1995 Playing two games. In Elusive Peace: Negotiating an End to Civil Wars, I.William Zartman, ed. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

Faure, Guy Olivier, and Zartman, I.William, eds. Forthcoming Escalation and Negotiation. Laxenburg: International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis.

Fisher, Roger, and Ury, William 1991 Getting to Yes. New York: Bantam.

Forrester, J.W. 1961 Industrial Dynamics. New York: Wiley.

Golan, Matti 1976 The Secret Conversations of Henry Kissinger. New York: Bantam.

Goldstein, Joshua 1998 The game of chicken in international relations: An underappreciated model. Unpublished paper, School of International Service, American University, Washington, D.C.

Goulding, Marrack 1997 Enhancing the United Nations’ Effectiveness in Peace and Security. New York: United Nations.

Goodby, James 1996 When war won out: Bosnian peace plans before Dayton. International Negotiation 1(3):501–523.

Haass, Richard 1990 Conflicts Unending. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Hampson, Fen Osler 1996 Nurturing Peace. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace.

Hoffer, Eric 1951 The True Believer. New York: Harper.

Holbrooke, Richard 1998 To End a War. New York: Random House.

Hopmann, P.Terrence 1997 The Negotiation Process and the Resolution of International Conflicts. Columbia: University of South Carolina.

Ikle, Fred Charles 1964 How Nations Negotiate. New York: Harper & Row.

Jentleson, Bruce 1995 With Friends like These. New York: Norton.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Tversky, Amos 1979 Prospect theory: An analysis of decisions under risk. Econometrica IIIL(3):263–291.

Kelman, Herbert 1997 Social psychological dimension in international conflict. In Peacemaking in International Conflict, I.William Zartman and I.Lewis Rasmussen, eds. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace.

Kissinger, Henry 1974 New York Times. October 12.

Kleiboer, Marieke 1994 Ripeness at conflict: A fruitful notion? Journal of Peace Research XXXI(1):109–116.

1997 International Mediation. Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner.

Kleiboer, Marieke, and ’t Hart, Paul 1995 Time to talk? Cooperation & Conflict XXX(4):307–348.

Kriesberg, Louis, and Thorson, Stuart, eds. 1991 Timing the De-escalation of International Conflicts. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press.

Lachow, Irving 1993 The metastable peace. In The Limited Partnership, James Goodby, ed. Oxford: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Lax, David, and Sebenius, James 1986 The Manager as Negotiator. New York: Free Press.

Lederach, John Paul 1997 Building Peace. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace.

Licklider, Roy 1995 The consequences of negotiated settlement in civil wars. American Political Science Review LXXXIX(3):681–690.

Lieberfield, Daniel 1999a Conflict ‘ripeness’ revisited: The South African and Israeli/Palestinian cases. Negotiation Journal XV(1):63–82.

1999b Talking with the Enemy: Negotiation and Threat Perception in South Africa and Israel/ Palestine. New York: Praeger.

Maundi, Mohammed, Khadiagala, Gilbert, Nuemah, Kwaku, Touval, Saadia, and Zartman, I.William 2000 Entry and Access in Mediation. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace.

Mitchell, Christopher 1995 Cutting losses. Working Paper 9, Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, George Mason University, Fairfax, Va.

Mooradian, Moorad, and Druckman, Daniel 1999 Hurting stalemate or mediation? The conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, 1990–95. Journal of Peace Research XXXVI(6):709–727.

Moses, Russell Leigh 1996 Freeing the Hostages. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Nicholson, M. 1989 Formal Theories in International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nicolson, Harold 1960 Diplomacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norlen, Tove 1995 A Study of the Ripe Moment for Conflict Resolution and Its Applicability to Two Periods in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Uppsala: Uppsala University Political Science.

Nye, Joseph, and Smith, Roger, eds. 1992 After the Storm. Lanham, Md.: Madison Books.

Ohlson, Thomas 1998 Power Politics and Peace Politics. Uppsala: University of Uppsala, Department of Peace and Conflict Research.

Ohlson, Thomas, and Stedman, Stephen John 1994 The New Is Not Yet Born. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

Olson, Mancur 1965 The Logic of Collective Action. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Ottaway, Marina 1995 Eritrea and Ethiopia: Negotiations in a transitional conflict. In Elusive Peace: Negotiating an End to Civil Wars, I.William Zartman, ed. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

Pillar, Paul 1983 Negotiating Peace. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Pruitt, Dean G. 1981 Negotiating Behavior. New York: Academic.

1997 Ripeness theory and the Oslo talks. International Negotiation II(2):237–250.

Pruitt, Dean G., and Carnevale, Peter 1993 Negotiation in Social Conflict. Pacific Grove, Calif.: Brooks/Cole.

Pruitt, Dean G., and Olczak, Paul V. 1995 Approaches to resolving seemingly intractable conflict. In Conflict, Cooperation and Justice, Barbara Bunker and Jeffrey Rubin, eds. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Quandt, William B. 1986 Camp David. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

Raiffa, Howard 1982 The Art and Science of Negotiation. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Rothchild, Donald 1997 Managing Ethnic Conflict in Africa. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

Rubin, Jeffrey Z., Pruitt, Dean G., and Kim, Sung Hee 1994 Social Conflict. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Salla, Michael 1997 Creating the “ripe moment” in the east Timor conflict. Journal of Peace Research XXXIV(4):449–466.

Sambanis, Nicholas In press Conflict resolution ripeness and spoiler problems in Cyprus. Journal of Peace Research.

Sampson, Cynthia 1997 Religion and peacebuilding. In Peacemaking in International Conflict, I.William Zartman and I. Lewis Rasmussen, eds. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace.

Samuels, Richard, et al. 1977 Political Generations and Political Development. Boston: Lexington.

Sandefur, J.T. 1990 Discrete Dynamical Systems. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Saunders, Harold 1991 Guidelines B. Unpublished manuscript, Kettering Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Sen, Amartya 1970 Collective Choice and Social Welfare. San Francisco: Holden-Day.

Shultz, George 1988 This is the plan. New York Times, March 18.

Sisk, Timothy 1995 Democratization in South Africa: The Elusive Social Contract. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Snyder, Glenn, and Diesing, Paul. 1977 Conflict Among Nations. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Spector, Bertram I. 1998 Negotiation Readiness in the Development Context: Adding Capacity to Ripeness. Paper presented to the International Studies Association, Minneapolis, March.

Stedman, Stephen John 1991 Peacemaking in Civil War. Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner.

1997 Spoiler problems in peace processes. International Security 22(2):5–53.

Stein, Janice, ed. 1994 Getting to the Table. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Stein, Janice, and Pauly, Louis, eds. 1992 Choosing to Cooperate: How States Avoid Loss. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Taisier, Ali, and Matthews, Robert O., eds. 1999 Civil Wars in Africa: Roots and Resolution. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press.

Touval, Saadia 1982 The Peace Brokers. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

1996 Coercive mediation on the road to Dayton. International Negotiation I(3):547–570.

1999 Mediators’ Leverage. Paper prepared for Committee on International Conflict Resolution, National Research Council.

Touval, Saadia, and Zartman, I.William, eds. 1985 International Mediation in Theory and Practice. Boulder, Colo.: Westview.

Walter, Barbara F. 1997 The critical barrier to civil war settlement. International Organization LI(3):335– 365.

Walton, Robert, and McKersie, Richard 1965 A Behavioral Theory of Labor Negotiations. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Young, Oran, ed. 1975 Bargaining. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Zartman, I.William 1983 The strategy of preventive diplomacy in third world conflicts. In Managing US-Soviet Rivalry, Alexander George, ed. Boulder, Colo.: Westview.

1986 Ripening conflict, ripe moment, formula and mediation. In Perspectives on Negotiation, Diane BenDahmane and John McDonald, eds. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

1985/1989 Ripe for Resolution. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zartman, I.William, ed. 1995a Elusive Peace: Negotiating an End to Civil Wars. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

Zartman, I.William 1995b Negotiations to End Conflict in South Africa. In Elusive Peace: Negotiating an End to Civil Wars, I.William Zartman, ed. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

Zartman, I.William, and Aurik, Johannes 1991 Power strategies in de-escalation. In Timing the De-escalation of International Conflicts, Louis Kriesberg and Stuart Thorson, eds. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press.

Zartman, I.William, and Berman, Maureen 1982 The Practical Negotiator. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Zartman, I.William, and Rasmussen, J.Lewis, eds. 1997 Peacemaking in International Conflict. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace.

Zartman, I.William, and Touval, Saadia 1997 International mediation in the post-Cold War era. In Managing Global Chaos, Chester Crocker, Fen Osler Hampson, and Pamela Aall, eds. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace.