8

Interactive Conflict Resolution: Issues in Theory, Methodology, and Evaluation

Nadim N.Rouhana

Following Fisher (1997), I use the term interactive conflict resolution to denote1 “small group, problem-solving discussions between unofficial representatives of identity groups or states engaged in destructive conflict that are facilitated by [an] impartial third party of social scientist-practitioners” (p. 8). More broadly, interactive conflict resolution also refers to a field of study and practice that includes similar activities, the rationale for carrying them out, their short-term objectives, and their long-term impact on the dynamics of conflict.2 I use the term problem-solving workshop—the main intervention tool of interactive conflict resolution—to refer to the specific activities carried out by third parties in the small group meetings between participants from societies in conflict.

Interactive conflict resolution’s general goals are defined in terms of contribution—the nature and size of which are unclear—to the resolution of international conflict, particularly to ethnonational conflicts between identity groups. It is naive and misleading to consider interactive conflict resolution an alternative to the existing diplomatic and other means of conflict resolution. It is best conceived as a set of methods and activities that can be used by unofficial trained third parties in parallel to—not in lieu of—official efforts. As such, interactive conflict resolution faces a host of core theoretical and methodological questions. As an emerging field, in parallel to the expansion in practice and training, questions are raised about theories of conflict resolution that guide practice, methodologies used in research, and evaluation of interventions’ impact on the macro-dynamics of conflict.3 To increase confidence in this approach to practice, establish its relevance for policy makers, and enhance its legitimacy as an

academic field of study and research, interactive conflict resolution should be held to the same standards of scrutiny as other established fields.

This scrutiny will be expressed in three areas. First, programmatic attention should be focused on theory building that could guide the practice of interactive conflict resolution activities in the field; these activities should be anchored in theories of conflict and conflict resolution that delineate theory-guided goals for unofficial intervention in ethnonational conflict and variables that influence the achievement of these goals. Second, research efforts are needed to examine theory-driven hypotheses or to help theory-building efforts. This will require the development of methodologies for empirical testing of theoretical connections, practice-related hypotheses, impact of the intervention on conflict dynamics, the usefulness of various intervention tools to practitioners, and the comparative effectiveness of various approaches. Based on the accumulation of theoretically guided empirical evidence, the field can establish taxonomies of practice—descriptions of what methods work, in what type of conflicts, at what stage of conflict, and under what conditions. Finally, programs need to be developed that provide training in intervention techniques that are explicitly based on theoretical foundations and guided by research findings. The dynamic relationship among all three elements should help in strengthening the academic foundations of interactive conflict resolution and guide the practice carried out by its practitioners. It should also help provide a coherent basis for developing guidelines or standards of professional accountability.

Theory-building efforts and research activity can also be channels for mutual enrichment among scholars from international relations, political science, social psychology, sociology, and other disciplines. Increasing the relevance of practice based on this approach can open essentially needed channels of dialogue with policy makers and practitioners of other approaches. The inherent interdisciplinary nature of the field can provide scholars with a wealth of available theories and methodologies to draw on in the theory-building effort and in designing methodologies for empirical research.

In this paper I focus on what needs to be done to increase confidence in the interventions that practitioners of interactive conflict resolution advance and to enhance the field’s relevance to policy makers and academic study with special emphasis on two issues. The first is the need to formulate, and to develop methodologies to examine, theoretical connections among current intervention techniques, microobjectives in the problem-solving workshop, and macrogoals of changing the dynamics of conflict. The second is to more explicitly conceptualize the long-term impact of interactive conflict resolution and possible ways for assessing specific effects, even though their direct measurement may be infeasible

and their impact may be slow acting. In this context I note the inherent cognitive and motivational factors that increase the likelihood of overestimating the impact of interactive conflict resolution as well as ways to guard against such inclination; I also propose ways to increase the real impact of unofficial intervention—that is, the impact on the dynamics of the conflict on the ground.

METHODS AND OBJECTIVES IN INTERACTIVE CONFLICT RESOLUTION

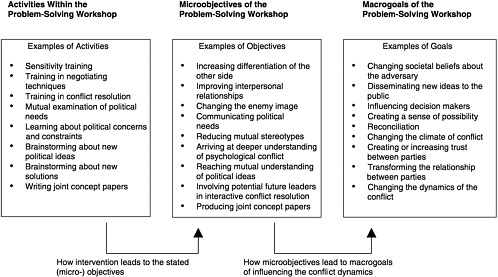

The discussion in this section focuses on the three components of interactive conflict resolution and the relationships among them. These components are (1) the methods and activities that compose the problem-solving workshop, (2) the microobjectives of the problem-solving workshop in the contained setting of small group discussions, and (3) the macrogoals of interactive problem solving in terms of its impact on the relationship between the societies in conflict. The two main theoretical paths between these components are (1) the links between the methods and the microobjectives and (2) the links between the microobjectives, if achieved, and the macrogoals. Perhaps the most important conceptual task for interactive conflict resolution is to delineate the theoretical relationships between the intervention method that a practitioner uses, the microobjectives of the intervention effort, and how these objectives could contribute to macrogoals of conflict resolution. In this section I describe the three components and the two theoretical paths that should connect them (see Figure 8.1).

Deconstructing the Problem-Solving Workshop: Methods and Activities

The package of activities that the problem-solving workshop is composed of should be described and deconstructed to its basic elements. This would include a description of the agenda the third party designs for the workshop, the content of the discussions that take place between participants, the level of interaction among participants promoted by the third party, and the type of intervention the third party employs. A full description of intervention methodology should also include the rationale for and process of participants’ selection and recruitment, the practical aspects of holding the problem-solving workshop, and assembling the third party.

Selection of the participants and the third party and some practical issues related to preparation for and conducting of the problem-solving workshop have been described elsewhere by some scholar-practitioners (e.g., Burton, 1987; Kelman, 1992; Mitchell and Banks, 1996; Rouhana and

Kelman, 1994). But from the limited description given in the literature of the actual activities that take place in unofficial intervention efforts the problem-solving workshop became a kind of an umbrella rubric under which activities that differ in fundamental ways are included and levels of interactions among participants that are qualitatively different are promoted by various third parties. One way to understand the differences is to look at the levels of interaction in the problem-solving workshop that facilitators promote. Surveying the literature I found three broadly defined levels of interaction that I described elsewhere: intrapsychic, interpersonal, and intergroup (Rouhana, 1998).

On the intrapsychic level the workshop participants deal with their feelings about the other side and with intrapsychic conflicts in the form of anxieties, ambivalence, and threats to one’s self-image. Issues such as healing of past psychological wounds and forgiveness of the other side as preconditions for reconciliation can take a central part in the discussion. Participants’ awareness of their own unconscious intrapsychic conflicts regarding these and other conflict-related issues and their dealing with intense feelings toward the other side are also central to the group discussion.4

On the interpersonal level, interactions between participants focus on the “here and now” in the context of generalizations, stereotypes about the other group and group members, possible misperceptions of the other side, and attributional errors about the other’s causes of behavior. Sensitivity training to avoid inadvertently hurting the other’s feelings and training in human communications skills across the conflict divide are central components of the group discussion.5 Although the group discussion of stereotypes and misperceptions has clear implications for intergroup relations, when the interpersonal level of analysis is applied, the interaction in the small group and its analysis are focused on the individuals themselves.

On the intergroup level, participants examine the dynamics of the conflict between the two societies and the collective needs and concerns that have to be met for a satisfactory political solution to emerge. Reference to the here and now of intergroup dynamics is only relevant to the extent that it helps participants understand the dynamics between the two societies at large. Taking the political realities into account, the thrust of the discussion is joint thinking about how to resolve the conflict between the two societies, with the specifics determined by the stage of the conflict. Improved communications, increased sensitivity, and mutual trust are not ends in themselves but are means to achieving a political goal: productive interaction about the intersocietal conflict issues that the participants are examining.6

The three levels of analysis are conceptually distinct and could indeed be addressed independently. In practice, too, the three levels are

distinguishable, although it is quite possible, for example, that the interpersonal level might be intermingled with the intrapsychic level of interaction. Or in unofficial interventions that focus on the political inter group level, while some references to interpersonal interactions might occur, they would not be encouraged except insofar as their use enhanced discussion at the intergroup level. For example, while the classical problem-solving workshop is designed to engage participants at the intergroup level, issues of interpersonal communications (group stereotypes, attributions about the other side’s behavior, and sensitivity to language used by each side) often get interlaced in the discussion but only as they contribute to analysis of the conflict at the group level. Indeed, when participants expect the workshop to focus on political analysis of the conflict, they might find interventions that do not maintain the same level of analysis improper and may express their dislike for such interventions.7

In addition to the fact that problem-solving workshops can be designed to foster different levels of analysis, there is considerable variability in what practitioners actually do and to what extent what they do is similar. For example, it is not clear what tools are used, how active and directive the third party is, what the agenda is that the third party prepares, or even what participants are invited to do. Yet some general description of the role of the third party is provided by some scholar-practitioners.8 For example, third parties can prioritize different levels of analysis even in the same workshop design. While Rouhana and Kelman (1994) emphasize the intergroup level focusing on structural political issues, d’Estree and Babbit (1998), working in the same framework, emphasize the importance of personal experiences and self-disclosure, emotional expressions, and the ability to recognize relational issues in interpersonal interactions in the problem-solving workshop. It is also possible that some practitioners use more than one level of analysis in the same problem-solving workshop and a combination of various activities such as problem solving, negotiation simulation,9 and lecturing (Gutlove et al., 1992).

Thus, one item on the conceptual and research agenda is to demystify the package called the problem-solving workshop by simply describing what it consists of in as much detail as possible. There should be enough elements described that other practitioners or scholars can recompose the problem-solving workshop for purposes of research, replication, or use. Whatever analogy is used to help describe the group dynamics in the problem-solving workshop—for example, mediation, negotiation, therapeutic process, or any small group dynamics—scholars and practitioners should be able to specify a more concrete set of activities that are transferable to other practitioners and replicable in other similar contexts by others.10 Practitioners should also be able to present some analysis of the dynamics that take place among the participants and the role of the third

party in directing these processes (e.g., Rothman, 1992; Rouhana, 1995b; Saunders and Slim, 1994).

Defining the Microobjectives of the Problem-Solving Workshop

The problem-solving workshop is the means of unofficial intervention that the third party uses with the implicit or explicit goal of introducing change in the dynamics of a conflict. The participants are the third party’s conduits to the desired change. So far, within the broad problem-solving workshop methodology, the target of change and the conduit of intervention in the conflict are assumed to be the participants’ views (not the third party’s) and some assumed activities that they can potentially undertake. Thus, on the microlevel the immediate objective of the intervention is some change in the way participants view the conflictual relationship and the future relationship with their adversary, and perhaps some activities the participants can undertake (by design or not by design), that can bring about some change on the macrolevel, that is, in the dynamics of the conflict on the ground. Therefore, practitioners should be able to define the intervention’s (micro-) objectives in terms of what changes they want the problem-solving workshop to bring about in the participants and what activities, if at all, they want the participants to undertake. In other words, if the problem-solving workshop is conceptualized (and defined as precisely as possible) as the independent variable (or more realistically a set of independent variables), practitioners should be able to define and describe their dependent variables and formulate a set of hypotheses about the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. Practitioners should be able to explain what changes they expect in the participants and/or what outcomes they want the workshops to achieve.

The dependent variables, or the objectives of many unofficial intervention activities, when extracted from published reports fall into four categories: psychological, such as forgiving the other and achieving psychological healing; interpersonal, such as reducing mutual stereotypes, attitudinal changes, improving interpersonal relationships, and establishing personal relationships across the divide of the conflict; political, such as changing participants’ views about the conflict through mutual learning about the other side’s political needs and political constraints and having participants create new ideas for solving particular problems between the two sides; and educational, such as training participants in conflict resolution logic and tools or integrative negotiation strategies. Not surprisingly, the first three sets of objectives are related to the three levels of interaction between participants that various problem-solving workshops promote, as described above.

Defining the Macrogoals of the Problem-Solving Workshop

The third major component of interactive conflict resolution is the goal or set of macrogoals that the unofficial intervention activity is intended to achieve. Problem-solving workshops are designed to influence the dynamics of conflict, even if in minor ways. Putting aside, for the moment, the difficulties of validating such influence, interactive conflict resolution should at least be able to articulate the goals of unofficial activity in terms of the intended impact on conflict dynamics on the ground.

Surprisingly, the goals of the problem-solving workshop are most often left undescribed. Except for the original work of Burton and his colleagues (Burton, 1986; Mitchell, 1981), in which the goals were defined as reaching a solution to the conflict and relaying it to decision makers (who, in that model, would have designated the workshop participants), most other approaches leave the goals undefined or most general. Thus, conflict resolution, or the more modest goal of contribution to the resolution of conflict and changing the dynamics of conflict on the ground, are frequently stated as the goal of unofficial activities. When it comes to the details of contribution, its nature, what exactly in the dynamics of the conflict on the ground is expected to change and through what mechanisms, or the estimated strength of such contribution, most unofficial interventions have little to say.

Without clearly predesignated expected outcomes and reasonably established means (both theoretical and empirical) to explain how these outcomes could be achieved, unofficial intervention is doomed to the status of double marginality: it will neither be taken seriously by policy makers and practitioners of the official diplomatic track nor will it succeed to become established as an academic discipline. It is to the theoretical paths that unofficial interventions need to establish between intervention and outcomes that I turn next.

Theoretical Path 1: How the Intervention Leads to the Stated (Micro-) Objectives

Practitioners and scholars of various approaches need to formulate the linkages between the particular methods they use and the objectives they define for their unofficial intervention. How, for example, would the chosen levels of interaction among participants and the intervention and facilitation of the third party lead to a stated set of objectives? Or, if the objective is to sensitize people to negotiation strategies or to expose them to conflict resolution methodologies, how, at least theoretically, could these “dependent variables” be traced to the particular activities in the problem-solving workshop? Thus, for example, training participants in negotiation methods could be described as one class of independent vari-

ables in certain problem-solving workshops (see, e.g., Gutlove et al., 1992, and Diamond, Chapter 7, this volume). Similarly, if one of the objectives were to get participants to think jointly of new ways to resolve a particular conflict-related issue, it would be necessary to show which activities and methods in the problem-solving workshop lead to such an objective. If healing and forgiveness are the objectives, practitioners will need to specify the tools and methods they use in order to achieve those ends.

An explicit theoretical connection of activities in the first component, the problem-solving workshop itself, to the set of dependent variables specified in the second component will help researchers in this field amass a set of testable hypotheses each of which can be examined by using the appropriate research design and methodology.11 Consistent with conventional scientific practice, the connection between the dependent and independent variables will have to be anchored in theoretical grounds, thus encouraging researchers to critically examine and/or develop appropriate theories for supporting these connections and to use theories and scientific findings from adjacent fields. This scientific effort will enrich the field both methodologically and theoretically.

Relating the variables in the first and second components and explicitly stating theoretical hypotheses that connect the two present a major part of a research agenda that researchers and scholars in conflict resolution, from different disciplines, should pursue in order to begin establishing an empirically demonstrated set of theoretical and empirical connections between the methods they use and the objectives they seek. Establishing such connections would provide practitioners with tested tools for practice and training and would bolster confidence in interactive conflict resolution intervention, not as a handful of artful techniques or a magic set but as a set of methods that are theoretically founded and empirically validated. These connections lend themselves to a variety of research methods that are described below.

Theoretical Path 2: How the Microobjectives Lead to Macrogoals of Influencing the Conflict Dynamics

Perhaps the most difficult task that scholars and practitioners of interactive conflict resolution face is demonstrating how the objective they designate for their problem-solving workshop, if attained, can lead to the change in conflict dynamics they seek to achieve—in other words, how the variables in the second component of interactive conflict resolution are connected to variables in the third set. For intervention in history it is difficult to achieve a level of clarity in explaining social and political change as mandated by standard models of social science, especially because relationships of cause and effect are hard to demonstrate as

Saunders (Chapter 7) argues and for other reasons elaborated on by Stern and Druckman (Chapter 2). Yet this difficulty should not become an excuse for dismissing the question or the propriety of the social science framework within which the question is raised.12 At a minimum, scholars and practitioners have to explicate the theoretical or conceptual relationships between the two sets of variables and produce a set of hypotheses on how the objectives of their problem-solving workshop can affect the dynamics of conflict. While demonstrating such connections empirically is not always attainable, producing clear theoretical connections is a minimum requirement without which the whole field of interactive conflict resolution risks becoming an empty exercise with little theoretical foundation and scientific value. It is also important, when possible, to produce indicators that can be used by scholar-practitioners to help evaluate these connections, such as the extent to which a connection is anchored in a solid theoretical foundation, empirical finding, or even common sense. Even if the hypothetical connections are not demonstrable by standard empirical research, their theoretical value could be judged by other scholar-practitioners.

Scholar-practitioners should be able to present their own theoretical connections depending on their disciplinary training, insights, or experience. When stated in the form of testable hypotheses, such hypotheses should, to the extent possible, be subjected to empirical tests. If that is not possible, other scholar-practitioners and policy makers will be in a position to evaluate these connections; offer their own analyses to support them, modify them, or challenge them; and decide for themselves whether interactive conflict resolution is a worthy effort.

A number of examples can serve to explain this point. As mentioned above, some interventions include elements geared toward training participants in the methodology of negotiation, and other interventions seem to include elements of “training” in various methods of conflict resolution. Others focus on improved communication, promoting understanding, establishing and/or strengthening interpersonal relationships, and lowering tension, anger, fear, or misunderstanding by humanizing the “face of the enemy” and giving people direct personal experience with one another (see, e.g., Diamond and McDonald, 1991). Similarly, Montville (1986, 1990) calls for more emphasis on psychological analysis, such as the examination of victimhood, mourning, and forgiveness. It would be necessary for any theory of conflict resolution to delineate the connections between these objectives (if met) and the goal of contributing to conflict resolution between parties on the ground, articulated in most specific theoretical terms. It will be left to other scholar-practitioners to evaluate (empirically and/or theoretically) whether achieving the objectives contributes to conflict resolution in the delineated ways.

To explain this last point, consider, for example, the problem-solving workshop that has been conducted for many years by Kelman and his colleagues on a one-time basis (Kelman and Cohen, 1976; Kelman, 1992) and later by Kelman and Rouhana on a continuing basis (Rouhana and Kelman, 1994). The objectives of the one-time workshops were defined in terms of having the participants understand the political needs and constraints under which each party operates. A major objective of the continuing workshops was defined in terms of jointly creating new ideas based on the needs of both parties and to have these ideas disseminated by the participants to upper-echelon leaders and constituencies; the goals were defined in terms of interjecting new political insights, acceptable to the mainstreams of both societies, into the political discourse of both parties. However, the potential impact of such goals on the dynamics of conflict is left unevaluated. Whether some of the ideas are really disseminated remains to be shown and to what extent they leave a discernable impact on the dynamics of conflict, even if they are, must be further explained. Kelman (1995) argues that the problem-solving activities he carried out over the years have contributed to the Oslo accords, which some consider as a breakthrough in Israeli-Palestinian relations, through three mechanisms: “development of cadres prepared to carry out productive negotiation; the sharing of information and the formulation of new ideas that provided important substantive input into the negotiation; and the fostering of a political atmosphere that made the parties open to a new relationship” (p. 21, italics in source). Although there is no clear empirical evidence to support these claims, once the theoretical connection is hypothesized, it will be up to practitioners (as well as participants) to decide whether the objective designated by an approach is valuable and whether the theoretical connection with the political goal delineated by the scholar-practitioners is sufficiently valid to be worthy of their effort.

Explaining why achieving the objectives of the problem-solving workshop is important depends, to a large extent, on one’s theory of conflict. Given the range of conflict theories developed in various disciplines and the varying levels of analysis used to explain the development and perpetuation of international and ethnonational conflicts (see, e.g., Levy, 1989; Singer, 1969), it is imperative not only to articulate the goals of a problem-solving workshop design but also to anchor the goals in these or other theories of conflict. This task is achieved by identifying the theory’s key causal variables and explaining how the workshop’s objectives affect these variables and, accordingly, the dynamics of the social or political conflict.

Whatever the theory of conflict, the goals of intervention depend to a large extent on the stage of conflict and perhaps the type of conflict under

consideration. One can divide the stages of conflict into three broad categories: prenegotiation, negotiation, and postnegotiation. The goals of interventions, and accordingly the objectives of the problem-solving workshop and the type of participants to be selected, depend, to a large extent, on the stage of conflict. There is no one problem-solving workshop that applies to all conflicts, at all stages, and for all goals. A major question that the research agenda should answer is that of which methods work, in what type of conflicts, at what stage of conflict, and under what conditions. A theory-driven taxonomy of interventions is needed to answer such a question (Rouhana and Korper, 1999).13

ASCERTAINING THAT INTERACTIVE CONFLICT RESOLUTION ATTAINS ITS MICROOBJECTIVES

As described above, one way to conceive of the political contribution of the problem-solving workshop to participants is the opportunity it provides for acquiring new ways of analyzing the conflict. This is achieved by learning about the dynamics of the conflict as perceived by the other side, their collective needs and fears, their political constraints, and the social and political dynamics that drive the conflict. This learning is a prerequisite for joint problem solving to take place in the workshop, for new ideas to be jointly generated by the participants, and for these ideas to be disseminated to the public with conviction. Thus, if the problem-solving workshop is to achieve its declared microobjectives, participants should leave the meeting with important learning about the other side, the range and depth of which depend on the exact objectives of the method and the success of the particular intervention effort.

For the change in the participants and the generation of new ideas to make any impact beyond the contained setting of the workshop, two additional objectives must be achieved: (1) the learning and the new ideas should be retained beyond the workshop setting and (2) the learning should also be used and the new ideas disseminated.

In summary, for interactive conflict resolution to achieve its microobjectives, three conditions are required: (1) participants should leave the meetings with new learning, (2) they should retain the learning when they return to the conflict arena, and (3) they should use it in their political discourse and behavior.

Does Learning Take Place?

Learning about the other side can be conceived in terms of increased differentiation of the other side’s politics and society, increased cognitive

complexity about its political needs and concerns, and increased humanization. This learning lays the groundwork for joint problem solving and joint generation of new options.

Differentiation

The homogeneous perception of the outgroup, even in the absence of conflict, is a well-established cognitive mechanism in the perception of others (Linville et al., 1986). Such homogeneity is typically exacerbated in conflict conditions, which promote psychological processes that essentialize and homogenize the other. Increased differentiation of the other side and expanded familiarity with the range of political thought and social forces are immediate achievements of problem-solving workshops. In many cases participants learn about the diversity of the other party’s political thinking, social forces, political structures, and the range of political perceptions and analyses of the other side.

The unique strength of this learning process is that it takes place first hand, directly from the other side, without the mediation of experts from one’s own party. The interactive aspect adds to the powerful impact that this learning might have on the participants. Having participants who are motivated to learn about the other and have the capacity to process complex (political) information provides two essential conditions for serious analysis of information (or what is known in social psychology as the central route to information analysis; see Petty and Cacioppo, 1986; Kressel et al., 1994).

Given the unique character of this learning process, its political function should not be underestimated, particularly for the party with less available resources to study the other. But even for the party that has resources, learning about the other side through the other’s own eyes is of unique value.

Cognitive Complexity

In addition to differentiation of the other side, participants learn about the vital political needs, political constraints, and political fears and concerns of the other. The dynamics of conflict and the nature of its discourse limit the opportunity for the needs, concerns, and constraints of the other side to be fairly presented to one’s own group. Awareness of one’s own needs and constraints often engulfs the political cognition of partisans in such conflicts.

Exposition to the other side’s needs in the careful process of a problem-solving workshop, which often have the mutual understanding of vital human needs on the top of the agenda, introduces participants to

new and important political data. Based on familiarity with the other’s needs, it is possible that participants’ cognitive complexity (Tetlock, 1984, 1986; Tetlock et al., 1984) will increase when thinking about the problem that faces both sides. Participants may then recognize the needs of the other group and perhaps try to incorporate them in their analysis of the conflict and their thinking about possible and desirable solutions. These changes can promote integrative approaches to reaching an agreement.

Humanization

Learning about the other side in the ways described above can contribute to a process of humanizing the other side by recognizing its human political needs and the forces that operate in its society. In addition, the interpersonal contacts that take place in the setting of a problem-solving workshop increase the likelihood of this process. Many workshop participants, however, choose to participate in these activities after having already engaged in the process of humanizing the enemy long before their participation.

Generating New Options

If the learning described above takes place, it might be possible for participants to generate new ideas and options to approach the conflict. According to Needs Theory (Burton, 1990), for example, ethnonational conflicts are over basic human needs. Therefore, in order for an agreement to stand a chance of acceptability by two groups in conflict, it will have to respond to the basic human needs of both groups, such as security, equity, and recognition. Mutual learning facilitates the generation of such agreements. The goal of intervention will be, correspondingly, to disseminate new ideas and insights (or even agreements) that reflect the basic human needs of both sides. Depending on the stage of conflict, the problem-solving workshop will be designed to generate such ideas and insights and to introduce them into the political discourse.

Interactive conflict resolution does not provide empirical evidence that the objectives described above are achieved, although the literature provides some anecdotal evidence. Conceptualizing the objectives is only the first step in the scientific inquiry into whether interactive conflict resolution attains its microobjectives. Theoretically based hypotheses should be developed to link interactive conflict resolution activities that various methodologies use with the objectives, and empirical research should provide the means of examining these hypotheses. These issues are examined below in the section on research and methodology.

Is Learning Maintained Outside the Contained Setting of the Problem-Solving Workshop?

The impact of a problem-solving workshop on the dynamics of conflict is assumed to be achieved through the impact of the participants on others. For participants to influence others, they should maintain the learning they acquire in the workshop and use it over time (in unspecified ways to be examined below) to influence the dynamics of the conflict between their communities.

Before examining how the learning is used, it would be important to determine whether changes in views last beyond the contained setting of the meetings. The idea is to examine whether the learning that is expected to take place generalizes from the insulated climate of the meetings out into the reality of conflict when participants go back to their home environments and, perhaps, whether they use their learning to analyze new events in ways they would not have done without the workshop experience.

It is certainly possible that deep insights that participants gain in a problem-solving workshop will last and be used in the analysis of new conflict-related events and that therefore participants will incorporate what they learned into their political discourse. However, it is also possible that a process of “unlearning” might take place when participants return to their natural conflict setting and are reexposed to continuing conflict-related incidents without the advantage of having them explained from the other’s point of view—a major benefit of the problem-solving workshop. It is not at all clear that insights gained about the other side’s ways of viewing events can generalize to the analysis of new conflict-related events, nor is it clear that participants have the motivation to do so. The dynamics of protracted conflict (see Rouhana and Bar-Tal, 1998) provide a psychological climate that is not conducive to maintaining such new insights. Conflict dynamics promote both cognitive (such as selective perception) and motivational processes (such as the motivation to see oneself in a positive light) that help perpetuate the conflict or even escalate it (Jervis, 1976; Rubin et al., 1994; White, 1984) and that therefore make it difficult to maintain such learning. Furthermore, conflict-related events that dominate the national agenda, and which are analyzed constantly from one point of view, provide ample opportunity for unlearning whatever insights the problem-solving workshop provided.

Indeed, our work gives a strong basis for believing that the process of learning that takes place in a problem-solving workshop does go through at least some unlearning outside the workshop and that some relearning is often needed if participants meet again for another workshop. For example, in the continuing workshop that brought together a

number of high-ranking Israeli and Palestinian participants for a number of years (Rouhana and Kelman, 1994; Kelman, 1997) and the joint Israeli-Palestinian Working Group on Israeli-Palestinian Relations in which a group of Israelis and Palestinians have been meeting periodically for more than three years, there were signs in each meeting that insights gained in previous meetings could not always be used by participants to analyze new events, particularly when the relationship on the ground witnesses intense mutual negative interactions.

In summary, learning retention cannot be taken for granted in a conflict climate. It can be examined in a number of ways in the context of a continuing and evolving conflict as described below.

Do Participants Use Learning in Their Political Discourse and Behavior?

For the problem-solving workshop to have political impact the participants must use the learning they gained in their political behavior. They should share some of their learning with others in their communities. Potentially, and depending on their access and influence, participants can share their new learning with decision makers and political leaders, or they can share it by writing, giving speeches or interviews to the news media, or in other interactions with members of their own group. To what extent participants share these educational outcomes with others is a question that research on interactive conflict resolution should try to answer. In some approaches a major criterion for recruiting participants is their ability to disseminate learning through a variety of means (such as heads of think tanks, senior journalists, leaders of grass-roots organizations, former high-ranking officials, senior academics, and so forth).

Indeed, for some intervention methods the dissemination of learning is central to the rationale of the problem-solving workshop. For example, in Kelman’s (1979, 1986) work and Rouhana and Kelman’s (1994) work, the selection of participants is central to the unofficial intervention effort precisely because participants are selected who occupy positions from which they can disseminate some of the new ideas they are expected to develop in the workshop and to decision makers and bodies politic.

It is quite possible that workshop participants do share some ideas with both leaders and publics in their communities. Indeed, there is good reason to believe that participants, particularly high-ranking people who work together on a continuing basis, will share some ideas with others in their communities. However, it is also possible that the conflict climate— which is often charged with emotions against the other and is less permissive of expressing empathetic views toward the adversary—deters participants from expressing their new learning in public or sharing it with

others. The conflict climate helps create a set of social norms that do not favor expressing conciliatory views or engaging in conciliatory actions and establishes contingencies of reward and punishment for deviating from these social norms. Many participants will be hesitant to speak in a way that shows understanding for their adversary for various reasons, not the least of which is being accused of siding with the enemy, betraying their community’s cause, becoming marginalized, or being delegitimized. Thus, even if participants retain the new learning and decide to share it with others, they might modify the way they present their insights in order to make them acceptable to others in the conflict climate, but in the process of both “packaging” the new insights and adding qualifications the insights lose much of their potential effectiveness.14 Because of these conflicting pressures on participants regarding dissemination of learning, the issue of using new learning should be a priority in the research agenda. Participants’ public political discourse can provide valuable research material in this regard.

DOES INTERACTIVE CONFLICT RESOLUTION ATTAIN ITS MACROGOALS?

While examining the objectives of the problem-solving workshop seems at least conceptually to be a forthright task whose achievement depends on the appropriate use of standard social science methodologies, examination of the macrogoals faces a number of major challenges. First, there is the lack of conceptual clarity as to the nature of the expected impacts and how they follow from the objectives of the problem-solving workshop. These objectives are defined in terms of changes in the participants that the scholar-practitioner would like to achieve, but the larger goals of the intervention relate to changes in the conflict dynamics that are often not clearly delineated by the scholar-practitioner, except in most general terms, and whose theoretical connections to the objectives of the problem-solving workshop are left uncharted.

Second, the goals of interactive conflict resolution are often confused with official diplomatic intervention goals that are defined more sharply in terms of bringing parties to the negotiation table, ceasing hostilities, or reaching agreements, depending on the stage of conflict. Unrealistic goals and unsubstantiated claims by scholar-practitioners only exacerbate this confusion and increase the likelihood that the same yardstick used in official intervention will be applied to evaluate unofficial intervention. Third, even if the theoretical connections between objectives and goals are delineated and the desired changes in the conflict dynamics are defined, examination of their achievement is most difficult because the expected impact on the dynamics of conflict between ethnonational communities is

too diffused to be assessed using standard research methodology or a traditional evaluation framework.

It is against these three challenges—lack of clarity about goals, the absence of theoretical connections between objectives of the problem-solving workshop and the desired effects on the conflict, and the evaluation of impact in terms of demonstrable achievements—that questions about the utility of interactive conflict resolution have been raised by some diplomats and scholars.15

As a beginning to responding to the first of these challenges, the goals of the problem-solving workshop should be defined depending on the stage of conflict, the nature of the conflict, and the particular dynamics of the conflict. With regard to conflict stage, in most general terms, before negotiations between the parties begin, the goals could be defined in terms of creating visions of peace that are acceptable to both communities and that can support dynamics for bringing parties to the negotiation table. In a negotiation stage the goals could be defined in terms of contributing to the achievement of an equitable agreement that can lead to just and stable peaceful relations between the two sides; and in a postagreement stage the goals could be defined in terms of supporting dynamics that can sustain peaceful relations. But the goals are also inextricably related to the theory of ethnonational conflict that one works with. Once the conflict stage and the conflict theory are incorporated into the goals of intervention, objectives that are theoretically guided to lead to these goals can be designed and participants who can help in achieving these goals can be selected.

These are broad definitions that will have to be fine-tuned. For example, as progress from one stage of conflict to another is nonlinear, in a negotiation stage the conflict could go through a number of phases: progress, stalemate, regression, progress, and so forth. Similarly, in a prenegotiation stage the conflict could be in a phase of complete absence of legitimized contact between political elites or in a phase where contact is legitimized but not formal. Because the goals differ at different stages, the relationship of goals to these substage fluctuations would need to be examined more closely.16

Once the goals are defined, the question becomes one of whether the microobjectives, even if achieved, lead to the foreseen impact. In other words, even if the ideas were successfully developed in the workshop and new insights were learned, and if these ideas and insights were retained, used, and successfully disseminated (i.e., the best-case scenario), are the macrogoals achieved, and how can the impact of learning and generating new ideas be measured? The effect of the participants’ learning on the dynamics of conflict is far from linear, nor is it the same for all participants in a given workshop. But it can be hypothesized that if participants share some of their learned differentiation, complexity, and humanization, this

learning will have similar effects on some audiences as it had on them. For example, it is possible that some learning that takes place in one problem-solving workshop will be shared when it is publicly or privately used by a participant (knowingly or unknowingly) in analyzing new conflict-related events. Or if participants share their learning in the form of new beliefs or new information about the other side, this may contribute to changing recipients’ attitudes toward their adversary or about the desirable form of relationship with the adversary. Social-psychological research offers empirical evidence about the importance of changing beliefs and of gaining new information for changing attitudes (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). Changed beliefs and attitudes can contribute to a public climate that is more receptive to political agreements with an adversary.

Do new ideas have a chance of being accepted by the publics and the elites? To what extent do they influence the dynamics of the conflict interaction and through what mechanisms? Answers to these questions lie in the complex nature of the process of social change, which defies the linear thinking of the standard social research methodologies.17 Accordingly, interactive conflict resolution could have a slow but dynamic and potentially important impact through a number of effects that characterize social change but that are hard or even impossible to measure.

CONCEPTUALIZING THE IMPACT OF INTERACTIVE CONFLICT RESOLUTION: PLAUSIBLE EFFECTS18

The impact of interactive conflict resolution should not be conceived against the goals determined by official diplomacy, such as reaching agreements between adversaries. Hoffman (1995) suggests that an unofficial intervention should be viewed as one initiative in a wider context of ongoing processes in which the effects of various efforts are dynamically interconnected. Similarly, Kelman (1992) argues that the objectives of unofficial intervention are different than those of formal international mediation. It contributes to creating an environment “that makes conflicting parties more ready to enter into negotiations, to bring the negotiations to a satisfactory conclusion, and to transform the relationship in the wake of a political agreement” (p. 69).

The impact should be conceived in terms of more complex and dynamic processes that reflect certain desired changes in a larger process of change in the conflictual relationship between the two societies. Impact in this context is not only unquantifiable using standard “hard-nosed” methodologies but also hard to conceptualize. But even if it is impossible to demonstrate definitively most of the effects that are hypothesized to constitute the ultimate impact of interactive conflict resolution, the analytical task of conceptualizing these effects and of anchoring them in theory is

not irrelevant.19 To the contrary, given the empirical difficulties, the theoretical delineation of plausible effects of the problem-solving workshop are essential in order to give the scholar-practitioner a handle on the theoretical evaluation of such efforts. Furthermore, although largely unmeasurable, some methodologies can be used to study the nature of some of these effects and even to assess their occurrence.20

The Exploratory Function

The contained and controlled climate of the problem-solving workshop allows for examination of how acceptable the ideas of one side are to participants from the other side—a function that becomes an integral part of the workshop activity and the effect of which is hard to measure or even identify. Throughout the process but particularly in the stage of joint thinking, participants present suggestions to deal with difficult conflict-related problems. By using the interactive process, participants learn that some of their ideas might fail to respond to or may even thwart vital political needs of the other side and what they need to do (including modifying their ideas) to make them acceptable or at least politically possible. They can examine the sources of objection and explore means to overcome the objection.

The exploratory function is important because participants themselves learn new insights about how the other side thinks about these issues. It is also important because it is possible that some participants can informally examine some of these ideas with policy makers. In a prenegotiation stage, when direct contact between the parties is not available, the problem-solving workshop can, in principle, fulfill a different exploratory function: it is possible that participants in prior coordination with policy makers can use the context of the problem-solving workshop to probe the acceptability of some ideas to the other side.21

Participants can also probe ideas that they develop in the problem-solving workshop with other politically influential colleagues and examine with them the political value and viability of these ideas. In a continuing workshop participants will be able to bring back the evaluation of others in their community and continue an iterative probation process that can improve further the ideas they examined earlier.

The Innovation Function

Once participants formulate new ideas acceptable to both sides, they can be instrumental in introducing those ideas to the political discourse in their political communities. They can share ideas with policy makers and political elites through their participation in seminars, professional and journalistic writings, speeches, and so forth. The potential for these ideas

to be accepted by the respective publics is always in question, yet three factors may increase the likelihood of their acceptability. First, the ideas are presented by the participants themselves, who are usually credible members of their respective societies—and credibility of the source has been demonstrated to be an important factor in persuasion (Hovland and Weiss, 1951). Second, participants can present the ideas with some authority because they can say that they know from their own contacts with participants on the side that these ideas are acceptable to many people from the other society. This adds to the authority of the source and the credibility of the ideas. Third, participants can explain that the ideas are based on the political needs and concerns of both sides, which strengthens the rationale for adopting the ideas and for seeing greater possibility that any formal agreements linked to those ideas has the potential to contribute to an enduring peace.

Until now there has been only anecdotal evidence of these innovation mechanisms, such as the observation that participants engage in dissemination of ideas to various publics, including higher echelons of political elites. They often present the ideas and say that they are acceptable to the other side and quote their own experience (within the ground rules of confidentiality, i.e., nonattribution to specific individuals in the workshops).

The Legitimization Effect

The problem-solving workshop can have an important indirect effect, depending on the stage of conflict, by legitimizing problem-solving activities between adversaries.22 The mere existence of the activity can, therefore, under some circumstances be a contribution. For example, in a prenegotiation stage a problem-solving workshop can contribute to a political climate that legitimizes meetings between adversaries. Often contacts are not legitimate, or even legal, for one side and sometimes for both sides.

Prior to the peace process between Israel and the Palestinians, Israel rejected the idea of negotiating with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and for Israelis to meet with the PLO representative was a violation of Israeli law. At the same time Palestinians sought recognition of the PLO by Israel. In meetings between high-ranking Israelis and Palestinians (Rouhana and Kelman, 1994), Palestinian participation was conditioned by having the explicit approval of the PLO and having a PLO member as a participant. For the Palestinians, whose position at the time called for direct negotiation between Israel and the PLO, such participation provided political gain. For many years left-wing Israelis had been meeting with PLO representatives, thereby giving some legitimacy to talking to the PLO. But the participation of high-ranking mainstream Is-

raelis increased the legitimacy effect. Indeed, the PLO representative met within the context of a problem-solving workshop with Israeli Knesset members, a former ambassador, and a future minister in the Israeli cabinet. Although confidential, the meetings were not secret and it was the responsibility of the participants to get the political clearance they needed and to report about the meetings to policy makers. Once open channels of negotiation between Israel and the PLO were established, the participation of a PLO representative was no longer a political condition for Palestinian participation.

The legitimizing effect works by gradually accustoming the public to these kinds of meetings and by increasing the political options for the parties, so that if negotiation with the other side is to be held officially the unofficial meetings would have contributed by preparing the public for such possibilities and reducing the intensity of opposition.

The Accumulation Effect

Interactive conflict resolution can contribute to changing the dynamics of conflict by gradually accumulating public opinion in favor of negotiation or a negotiated agreement. Conflict has the powerful impact of unifying societies at a time of open confrontation with the enemy. But when the possibility of negotiating with the enemy emerges, deep division in the society may surface.

One effect that interactive conflict resolution can have on the dynamics of conflict is to bolster the forces that favor negotiation. The “dialogue industry” that mushroomed between Israelis and Palestinians before the Oslo process may have strengthened the hands of the Israeli government in pursuing open negotiation with the PLO. Political and intellectual elites from the Israeli left and the Labor Party, who by then had participated in the hundreds of meetings organized over many years in many parts of the world (particularly by European institutions), introduced to some segments of the Israeli and Palestinian elites a new way to view the other side. Perhaps the accumulation of so many participants tipped the balance in a divided society in favor of negotiation. This repertoire of support could have made it possible for the Israeli government to make the daring step of negotiating with the PLO at a time when its strategic interests favored such a step. There is no evidence to support the argument that these meetings themselves pushed the Israeli government to take these steps. Strategic considerations related to the continued confrontation with the Palestinians on the ground and the weakening of the PLO in the aftermath of the Gulf War, as well as international changes after the fall of the Soviet Union and the emergence of the United States as the hegemonic power in the area, together played a major role in moving the

Israeli government to consider such an option. But once the possibility emerged for negotiations with the PLO, the potential contribution of the accumulated repertoire of support was there to be taken advantage of.

Although the move toward the Israeli-Palestinian negotiation could provide a good example of this potential effect, it should be noted that this conflict, for a variety of reasons beyond the scope of this paper, received unprecedented attention in many international circles. The European Community, in particular, has been involved in a steady effort to organize meetings between Israelis and Palestinians (which continue until now in different forms), a phenomenon that many in the region call the dialogue industry. It is not clear whether other conflicts could have received the same level of attention and resources to make such an effect potentially possible.

The Clarification Effect

The in-depth analysis of political issues that the interactive conflict resolution makes possible, particularly when workshops between the same participants are held on an ongoing basis, gives participants (and third parties) good understanding of what is possible and what is not in the existing structure of power relations. It shows the boundaries of agreement between the two sides and the margins of disagreement. It can also provide participants with an understanding, based on comprehension of the other side’s political needs, of the contours of agreements that are acceptable to the other side and the extent of possible concessions.

When discussions get specific and participants focus on conflict-related issues in detail, the problem-solving workshop can help define more precisely the zones of agreements and disagreements on each issue. Problem-solving workshops can try to bridge the gap between the two sides and therefore demonstrate the extent to which problem solving can reduce differences between the parties as well as the areas that cannot be bridged.

Such analysis provides an important understanding of the conflict issues. The joint analysis has the potential to provide the parties, particularly the third party, with valuable insights about the general shape of an agreement that would be agreeable to both sides. The dissemination of such analysis can introduce into the public debate valuable information and joint insights that can be examined, improved, or modified. It can also give formal negotiators on both sides useful information about what the areas of disagreement are on important conflict issues and what tradeoffs are possible. These insights can be even better used to increase the potential impact of interactive conflict resolution.

The Preparatory Effect

The accumulated effect of interactive conflict resolution activities can increase the mutual familiarity with the other side in many areas: political concerns, social and political structure, sensitivities to language, and so forth. A broad understanding of these issues can become most useful when an official process of negotiation starts. Interactive conflict resolution could contribute to a political culture of the political elite that is familiar with the other. This familiarity can help establish a smoother negotiation process. It is even possible that people who participate in a problem-solving workshop will take part in policy-making decisions or in think tanks involved in producing policy recommendations about managing conflict or negotiation with the other side. In this case familiarity with the other side’s political landscape can be a major asset in contributing to better understanding.23

Continued meetings between participants create a network of communication, albeit limited, across the divide that participants use in their various activities. Thus, participants can and do call on each other for participation in conferences, meetings, and journalistic interviews. These networks can become a useful preparatory infrastructure for future structural cooperation between the parties after an agreement is achieved.

The Latency Effect

The problem-solving workshop is designed with the idea of providing participants from both sides equal power at the meetings themselves. This is reflected in the methodology of considering the political needs of each side equally when thinking about new ideas for resolving the conflict. However, the power equality in the problem-solving workshop cannot ignore the power relations on the ground. The ideas developed in the workshop, therefore, while not reflective of the power asymmetry on the ground, cannot ignore it either. Many ideas developed in such a context could be used as the foundation for equitable agreements, but on the ground they are not usually acceptable to the party that has more power because they do not fully reflect the power asymmetry in its favor.

However, this is not to say that these ideas have no use at all. In addition to their educational value, once they enter the political discourse about the conflict these ideas have the potential to maintain a latent effect, even if they are initially dismissed. They can become useful for either party when the structural power between the two parties changes for whatever reason (military balance, demographic change, external pressure, or change in leadership). The changed power relations can become

the proper context for ideas developed in interactive conflict resolution to be available in the right time—an investment that pays off. This is why Alexander George (personal communication, 1997) calls this potential contribution of interactive conflict resolution a capital investment in political ideas. The unique value of these ideas, which increases the chances of payoff, is their foundation in both sides’ political needs and their development by participants from both sides in a context that is less bound by power relations than the negotiation context. However, as the investment analogy suggests, the return could be nil, or the ideas may eventually be lost if too much time passes without any progress.

The latency effect of ideas developed in the problem-solving workshop can become relevant for both decision makers and publics. Not only could changes in the structure of power relations render new ideas more relevant but also the climate of the conflict such as a hurting stalemate, or its opposite, improved climates, brought about by internal or regional changes. Dismissed, for example, in the context of open violence or gross power asymmetry, these ideas can become more acceptable in the context of negotiation or as a basis for negotiation.

The value of the investment is very hard to measure. But it is clear that one can think of numerous circumstances under which such an investment will be wasted. However, it is also possible to think of political circumstances that can make use of such ideas and that will need ideas to be available for use to advance relations between conflicting parties. The circumstances that control the value of the investment fall completely outside the contained limits of the problem-solving workshop.

RESEARCH AND METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES

Mapping the theoretical connections between intervention methods, objectives, and goals serves not only to clarify theoretical assumptions but also to guide the research agenda. By the nature of the theoretical paths outlined above, the research agenda will require multiple methodologies that social scientists can use, depending on the question they ask: survey research, interviews, archival research, discourse analysis, limited ethnographic studies, and controlled laboratory and field experiments. Indeed, the interdisciplinary nature of the field could be utilized effectively if the proper disciplinary research methods are tailored to the various questions that scholars and practitioners from different fields raise.

Attaining and Retaining the Desirable Change

The field of conflict resolution, as practiced, does not actually have a broad range of techniques to offer the scholar-practitioner. Because the

problem-solving workshop is the single most important format that the field of interactive conflict resolution has developed, it is the focus of the research agenda. Therefore, the first theoretical path outlined above, that which connects the elements of the problem-solving workshop to the various objectives it is designed to achieve, becomes a major item on the research agenda.

It cannot be assumed that any “package” of the potential elements that can compose the problem-solving workshop will achieve the objectives designated by the scholar-practitioner. Even the most simple goals, such as achieving change in stereotypical attitudes, cannot be taken for granted or assumed to occur just by bringing parties in conflict into contact with each other. Nor should it be assumed that any activity of contact between adversaries is better than no activity, a widely held assumption in the field. Indeed, the social-psychological research points to strict conditions under which contact between members of adversarial groups should take place if attitudinal change is to be achieved—such as equal status of the participants, institutional support by both sides in terms of lending social legitimacy for such contacts, common goals for all participants, and interdependency between the two sides (Amir, 1976; Hewstone and Brown, 1986; Stephan, 1985). Furthermore, it is not clear that problem-solving workshops geared toward a goal of changing stereotypes are of use to all parties at all times, regardless, for example, of the power asymmetry between the parties (Rouhana and Korper, 1997). Similarly, the history of reported meetings between adversaries indicates that sometimes the opposite of the desired goals could occur, as critics of Doob’s intervention in Northern Ireland claim. (See report about the intervention and the ensuing controversy in Doob and Foltz, 1973, 1974; Boehringer et al., 1974; Alvey et al., 1974).

The refinement of intervention tools and the establishment of a repertoire of activities to be used in the problem-solving workshop require empirical examination of the elements in the problem-solving workshop and the methods of third-party facilitation that lead to the intended outcomes. By using experimental research methods it will be possible to examine hypotheses connecting some elements of the workshop package of activities with intended outcomes, to compare various methods of intervention, and to test and compare the effectiveness of various third-party intervention techniques (for a similar approach to negotiation, see Druckman, 1993).

There are, however, serious limitations to the possibility of using experimental methods when conducting real-life intervention in ethnonational conflict for practical reasons (such as using control groups) and ethical considerations (such as using the participants for experimental purposes). From a practical point of view, in order to carry out an experimental study it would be necessary to compare the experimental group—

the group that participates in the problem-solving workshop—with a control group (or a number of control groups) that does not receive the same intervention or that receives no intervention at all. It would also be necessary to have the participants in the experimental and the control groups drawn randomly from a broad pool of potential participants and then randomly assigned to the experimental and the control groups and for the third-party facilitators to be kept in the dark as to the purpose of the study. In addition, research tools such as questionnaires before and after the intervention can constitute a serious intrusion into the intervention process that raises awareness about the questions of concern to the researcher; furthermore, many participants will resent the idea of being used as experimental subjects. The intrusion also introduces a sense of artificiality into the intervention, which itself reduces the likelihood that the intervention will contribute either to the participants or to the larger goals of conflict resolution.

There are also serious ethical considerations against using experimental designs, such as assigning participants to control groups, using participants as subjects, and the inevitable deception involved in keeping the goals of the experiment from participants. In addition, there might be a violation of confidentiality—as all information about the workshops will become a public record—which many problem-solving workshop organizers see as essential to the process.

Although interactive conflict resolution is not inherently conducive to experimental studies, such studies are not impossible to conduct. For example, simulated conflict situations can be used with student populations (as done, for example, by Druckman et al., 1988), as is the case with other experimental designs in social sciences in the academic context. A second approach would be to conduct field experiments with high school and university students on real-life conflicts and interventions, such as using field studies in the tradition of Sherif’s (1967) classical conflict studies. It would also be possible to conduct studies using quasi-experimental designs (Campbell and Stanley, 1963; Stern and Kalof, 1996) that employ unobtrusive measures or measures that are minimally intrusive to the intervention process (such as observing and recording the extent of social interaction between participants from opposite sides).24 Both the field experiments and the quasi-experimental studies in the context of real social and political conflicts are essential for attaining the external validity that laboratory and survey studies lack. More effort is needed to validate the effects that the laboratory studies demonstrate in the natural settings of conflict.

For each of the ways described above, consider the following hypothetical example. Think of the independent variable as the primary activity carried out by the third party in a problem-solving workshop. Com-

pare the following four classes of activities: (1) facilitating the presentation of the political needs of each party, (2) sensitivity training, (3) examination of issues of forgiveness, and (4) training in principled negotiation. Design an intervention for each activity that takes two sessions of one and one-half hours each. Consider a list of possible objectives as dependent variables: cognitive complexity in thinking about the conflict, acceptability of the other side’s political needs, changes in stereotypes about the other, willingness for reconciliation, and ability to reach an integrative agreement. It is possible to design experimental studies to examine the effectiveness of the various interventions in achieving the designated goals and in comparing which of the interventions is more effective in achieving which outcomes. It is also possible to examine more directed hypotheses based on theoretical foundations, such as that mutual examination of political needs will increase cognitive complexity more than sensitivity training. Such a hypothesis could be anchored in the social-psychological research on cognitive complexity (Tetlock, 1984, 1986; Tetlock et al., 1984).

Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow for the examination of hypotheses that are generated by and anchored in the social-psychological literature, theories of negotiation, and theories of conflict resolution. The studies could be fine-tuned to examine hypotheses about learning that takes place in problem-solving workshops and changes in participants’ attitudes and cognitive styles, to compare the effectiveness of different methods in reaching agreements (Cross and Rosenthal, 1999), to examine questions about third-party perceived neutrality and bias (Arad and Carnavale, 1994), to identify which third-party interventions are most useful to achieve the designated objective, and so forth.

Carrying out research by using simulations and field studies, although tedious and resource intensive, should provide scholar-practitioners with empirically validated findings about useful methods, activities, and third-party techniques. Like experimentation in many other social issues, these studies will no doubt raise some ethical questions; similarly, studies based on simulated conflict raise questions about external validity. External validity is also an issue for field research insofar as any study is limited in space, time, setting, and so forth. Similarly, there is a problem of sampling in terms of defining the universe of situations of which the simulation or field experiment is representative. (For further discussion of these and other problems in the context of international conflict resolution, see Chapter 2 by Stern and Druckman). But these are not insurmountable problems, as one can benefit from the long tradition of experimental studies in the social sciences.

Although experimental studies can be applied in a straightforward way to examine hypotheses in this theoretical path, other techniques also

can be used. When records of meetings are available for examination, qualitative techniques can be used to examine some hypotheses in this path—for example, that participants show new learning or that participants get involved in joint problem solving. Similarly, in-depth analysis of meetings transcripts, videotapes, or audiotapes and interviews with participants could help answer relevant questions of interest.

Take, for example, the issue of retained learning. Interviews held with participants at various times after the problem-solving workshop can provide introspective data on this issue. Participants might point to incidents that either make them strengthen or weaken their learning and can share their experience of whether it was difficult to maintain their new learning. The disadvantage of such interviews is that they can only tap into change processes of which the participant is aware. Many changes in a person’s views, attitudes, and even behavior can take place without full awareness (Langer, 1989). Analysis of participants’ writings and speeches can also help in examining the retention of new learning and its use in interpreting related political events.

In other cases, when ethical and practical problems can be surmounted, additional research methods can be used. For example, when workshop participants are students who agree to participate in research efforts, it is possible to use quasi-experimental designs to examine learning retention. Bargal and Bar (1992) compared scores of attitudinal changes in Arab and Jewish high school student workshop participants with students who had not participated in the workshops. The findings compiled for five separate years from 1984 to 1988 showed that in some years change took place in “favorable” directions and in other years in “unfavorable” directions. The authors concluded from the fluctuations in change that attitudinal changes might be more closely related to major political events constantly taking place in the conflict area than to workshop participation. Bargal and Bar concluded that their “questionnaires do not seem to capture the full range and depth of change that has occurred among workshop participants” (p. 151) and recommend qualitative methods to examine change.

The question of retention of new learning in a nonconducive conflictual environment can be studied, in theory, with other methodologies. Social scientists can use other experimental designs, as discussed above, to examine the extent of learning retention in conflict settings and to test variables that increase or decrease the likelihood of retention in such climates.

Assessing the Impact of the Conceptualized Effects

Another major item on the research agenda is the second theoretical path—that which connects the microobjectives of the problem-solving

workshop with the goals of changing the dynamics of conflict on the ground. I have suggested conceptualizing the theoretical connections as effects whose impacts cannot be precisely measured. Although mostly unmeasurable, it is important to estimate the overall impact of these effects on the dynamics of conflict. After all, given the absence of hard evidence, many scholars and practitioners will make their own judgments about the value of interactive conflict resolution based on some assessment of the hypothesized impact. Scholars and practitioners should identify ways to provide their audiences with as much information as possible to make such a judgment.