11

Electoral Systems and Conflict in Divided Societies

Ben Reilly and Andrew Reynolds1

This work examines whether the choice of an electoral system in a culturally plural society can affect the potential for future violent conflict. We find that it can, but that there is no single electoral system that is likely to be best for all divided societies. We distinguish four basic strategies of electoral system design. The optimal choice for peacefully managing conflict depends on several identifiable factors specific to the country, including the way and degree to which ethnicity is politicized, the intensity of conflict, and the demographic and geographic distribution of ethnic groups. In addition, the electoral system that is most appropriate for initially ending internal conflict may not be the best one for longer-term conflict management. In short, while electoral systems can be powerful levers for shaping the content and practice of politics in divided societies, their design is highly sensitive to context. Consideration of the relationship between these variables and the operation of different electoral systems enables the development of contingent generalizations that can assist policy makers in the field of electoral system design.

INTRODUCTION

Several fundamental assumptions that underlie the thinking of many Western policy specialists are called into question by the evidence assembled here concerning the relationship between conflict and elections. The first assumption, derived from Western experience, is that “free and fair elections” are the most appropriate way both to avoid and to manage

acute internal conflict in other countries. The second assumption, which goes hand in hand with the first, is the implicit approval of “winner take all” models of both government and election and disapproval of arrangements that emphasize power sharing and cooperation. The third, again derived from Western experience, is that the types of electoral systems used in the West can be successfully transplanted to the developing world. A final assumption is that stable democracies need to be based on a system of individual rights rather than group rights. This work, to varying degrees, calls all of these assumptions into question.

The multicountry evidence cited here offers some insights about how to diagnose a country’s situation for the purpose of selecting an electoral system that can help that country address its communal conflicts peacefully. Realistic diagnosis of key social-structural issues is a necessary precondition to designing a successful system. In practice, there is little evidence of such diagnosis at work in the historical record. Moreover, the choice of an electoral system involves tradeoffs among a number of desirable attributes. Thus, the role of local actors, who can draw both on international experience and on their knowledge of domestic conditions and priorities, is key.

Institutions, Conflict Management, and Democracy

The study of political institutions is integral to the study of democratization because institutions constitute and sustain democracies:2 as Scarritt and Mozaffar succinctly summarize, “to craft democracies is to craft institutions” (1996:3). Perhaps most important for newly democratizing countries is the way that institutions shape the choices available to political actors. Koelble notes that this emphasis on “rules, structures, codes, and organizational norms” is based upon Weber’s view of organizations as constructs designed to distribute rewards and sanctions and to establish guidelines for acceptable types of behavior (1995:233). March and Olsen argue that “constitutions, laws, contracts, and customary rules of politics make many potential actions or considerations illegitimate or unnoticed; some alternatives are excluded from the agenda before politics begins, but these constraints are not imposed full-blown by an external social system; they develop within the context of political institutions” (1984:740). In his important 1991 book Democracy and the Market, Adam Przeworski develops a concept of democracy as “rule open-endedness or organized uncertainty…and the less the uncertainty over potential outcomes the lower the incentive for groups to organize institutionally” (1991:13). Thus his influential conclusion, central to the spirit of this paper, was a recognition that democratic government, rather than oligarchy or authoritarianism, presented by far the

best prospects for managing deep societal divisions, and that democracy itself operates as a system for managing and processing rather than resolving conflict.3

In their preface to Politics in Developing Countries, Larry Diamond, Juan Linz, and Seymour Martin Lipset argue that institutions influence political stability in four important respects:

-

Because they structure behavior into stable, predictable, and recurrent patterns, institutionalized systems are less volatile and more enduring, and so are institutionalized democracies.

-

Regardless of how they perform economically, democracies that have more coherent and effective political institutions will be more likely to perform well politically in maintaining not only political order but also a rule of law, thus ensuring civil liberties, checking the abuse of power, and providing meaningful representation, competition, choice, and accountability.

-

Over the long run well-institutionalized democracies are also more likely to produce workable, sustainable, and effective economic and social policies because they have more effective and stable structures for representing interests and they are more likely to produce working congressional majorities or coalitions that can adopt and sustain policies.

Lastly, (iv) democracies that have capable, coherent democratic institutions are better able to limit military involvement in politics and assert civilian control over the military (1995:33).

Institutions and Democratization in the Developing World

While accepting that throughout the developing world the societal constraints on democracy are considerable, such constraints still leave room for conscious political strategies which may further or hamper successful democratization. As a result, institutions work not just at the margins, but are central to the structuring of stability, particularly in ethnically heterogeneous societies. Scarritt and Mozaffar push the critical role of institutions even further by arguing that distinct institutional arrangements not only distinguish democracies, but also invest governments with different abilities to manage conflicts, and thus that the survival of third-wave democracies under extremely adverse conditions often hinges on these institutional differences (1996:3).

Institutional design takes on an enhanced role in newly democratizing and divided societies because, in the absence of other structures, politics becomes the primary mode of communication between divergent social forces. In any society, groups (collections of individuals who identify some sort of mutual bond) talk to each other—sometimes about resolving

distributive conflicts, sometimes about planning for the national future, and often about more mundane issues of everyday concern. In the pluralist democracies of the West, there are a variety of channels of communication open through which to carry on these conversations. Individuals from different cultures and perspectives can communicate with each other through the institutions of civil society via the press, social and sporting clubs, residence associations, church groups, labor unions, and so on.4

In fledgling democracies, however, where society is more deeply divided along ethnic, regional, or religious lines, political institutions take on even greater importance. They become the most prominent, and often the only, channel of communication between disparate groups. Such societies do not yet have the mixed institutions which characterize a broad civil society. Sporting, social, and religious groups are rigidly segregated, and various peoples do not live together, play together, or really talk to each other. Similarly, many new democracies do not yet have a vigorous free press where groups can talk. This holds true in the West as well, where different media outlets speak to different social groups or classes, and where cities are often segregated along racial, ethnic, and economic lines; but divided societies in the developing world often represent the extreme of the continuum, and that is why political institutions exist as the primary channel of communication.

Because political institutions fulfill this role as the preeminent method of communication, they must facilitate communication channels between groups who need to talk. If they exclude people from coming to the table, then their conflicts can only be solved through force, not through negotiation and mutual accommodation. Further, those doing the talking, the representatives, must be just that—representative. To be able to make promises and then deliver on them, each political representative needs to be accountable to his or her constituency to the highest degree possible through institutional rules. The extent to which institutional rules place a premium on the representational roles of such figures, or rather seek to break down the overall salience of ethnicity by forcing them to transcend their status as representatives of only one group or another, is central to the scholarly debate about political institutions in deeply divided societies.

The Validity of Constitutional Engineering

There is little dispute that institutions matter, but there is much greater dispute regarding how much one can (or would wish to) engineer political outcomes through the choice of institutional structures. In this regard there exists an important distinction between an institutional choice approach and those who seek institutional innovation through constitutional engineering to mitigate conflict within divided societies. Sisk notes that

“there has been an implicit assumption by scholars of comparative politics who specialize in divided societies that such political conflict can be potentially ameliorated if only such societies would adopt certain types of democratic institutions, that is, through ‘political engineering’” (1995:5). Indeed, Horowitz proposes that “whatever their preferences, it remains true that a severely divided society needs a heavy dose—on the engineering analogy, even a redundant dose—of institutions laden with incentives to accommodation” (1991:280–281). Similarly, Sartori argues that “the organization of the state requires more than any other organization to be kept on course by a structure of rewards and punishments, of ‘good’ inducements and scary deterrents” (1994:203).

However, Sisk runs counter to Horowitz, Lijphart, Sartori, and others in arguing that constitutional engineering should not be the primary focus of research: “most scholarship about democracy in divided societies centers too much on examining the best outcomes, as opposed to looking at the ways these outcomes evolve through bargaining processes” (1995:18). Indeed, Elster supports Sisk with the view that “it is impossible to predict with certainty or even qualified probability the consequences of a major constitutional change” (1988:304). Elster and Sisk remain in the minority on this question, given that most comparative political scientists would be happy to predict with “qualified probability” the results of a shift in electoral law or democratic system. As Sartori correctly notes, if we follow Elster’s somewhat defeatist logic, then “the practical implication of the inability of predicting is the inability of reforming” (1994:200). There seems little reason to give up the potential power of institutions for conflict resolution if we are confident of some degree of predictive ability when it comes to institutional consequences.

Ultimately, there is a temporal dimension to both constitutional design and the politics of institutional choice. Political actors in a fledgling democracy may choose certain structures (rationally) because they maximize their gain in the short term. Thus, negotiators may not alight upon more inclusive structures recommended by political scientists posing as constitutional engineers. However, the promise of constitutional engineering rests on the assumption that long-term sociopolitical stability is the nation’s overarching goal; and the institutions needed to facilitate that goal may not be the same as those which provide maximum short-term gain to the negotiating actors in the transitional period. Thus, institutional choice and constitutional engineering are, in practice, compatible approaches. One seeks to understand what drives short-term bargains, while the other seeks to offer more long-term solutions with the benefit of comparative cross-national evidence. The task of the constitutional engineer is not only to find which institutional package will most likely ensure democratic consolidation, but also to persuade those domestic politicians making the decisions that they should choose long-term stability over short-term gain.

Electoral Engineering and Conflict Management

The set of democratic institutions a nation adopts is thus integral to the long-term prospects of any new regime as they structure the rules of the game of political competition. Within the range of democratic institutions, many scholars have argued that there is no more important choice than which electoral system is to be used. Electoral systems have long been recognized as one of the most important institutional mechanisms for shaping the nature of political competition, first, because they are, to quote one electoral authority, “the most specific manipulable instrument of politics”5—that is, they can be purposively designed to achieve particular outcomes—and second, because they structure the arena of political competition, including the party system; offer incentives to behave in certain ways; and reward those who respond to these incentives with electoral success. The great potential of electoral system design for influencing political behavior is thus that it can reward particular types of behavior and place constraints on others. This is why electoral system design has been seized upon by many scholars (Lijphart, 1977, 1994; Sartori, 1968; Taagepera and Shugart, 1989; Horowitz, 1985, 1991) as one of the chief levers of constitutional engineering to be used in mitigating conflict within divided societies. As Lijphart notes, “if one wants to change the nature of a particular democracy, the electoral system is likely to be the most suitable and effective instrument for doing so” (1995a:412). Nevertheless, the fact that electoral system design has not proved to be a panacea for the vagaries of communal conflict in many places has shed some doubt upon the primacy that electoral systems are given as “tools of conflict management.” What we attempt to do in this paper is assess the cumulative evidence of the relationship between electoral systems and intrasocietal conflict, and determine under what conditions electoral systems have the most influence on outcomes.

An electoral system is designed to do three main jobs. First, it translates the votes cast into seats won in a legislative chamber. The system may give more weight to proportionality between votes cast and seats won, or it may funnel the votes (however fragmented among parties) into a parliament which contains two large parties representing polarized views. Second, electoral systems act as the conduit through which the people can hold their elected representatives accountable. Third, different electoral systems serve to structure the boundaries of “acceptable” political discourse in different ways, and give incentives for those competing for power to couch their appeals to the electorate in distinct ways. In terms of deeply ethnically divided societies, for example, where ethnicity represents a fundamental political cleavage, particular electoral systems can reward candidates and parties who act in a cooperative, accommodatory manner to rival groups; or they can punish these candidates and

instead reward those who appeal only to their own ethnic group. However, the “spin” which an electoral system gives to the system is ultimately contextual and will depend on the specific cleavages and divisions within any given society.

That said, it is important not to overestimate the power of elections and electoral systems to resolve deep-rooted enmities and bring conflictual groups into a stable and institutionalized political system which processes conflict through democratic rather than violent means. Some analysts have argued that while established democracies have evolved structures which process disputes in ways that successfully avoid “conflict,” newly democratizing states are considerably more likely to experience civil or national violence (see Mansfield and Snyder, 1995). The argument that competitive multiparty elections actually exacerbate ethnic polarism has been marshaled by a number of African leaders (for example, Yoweri Museveni in Uganda and Daniel arap Moi in Kenya) in defense of their hostility to multiparty democracy. And it is true to say that “elections, as competitions among individuals, parties, and their ideas are inherently just that: competitive. Elections are, and are meant to be, polarizing; they seek to highlight social choices” (Reynolds and Sisk, 1998:18). Elections may be “the defining moment,” but while some founding elections have forwarded the twin causes of democratization and conflict resolution, such as South Africa and Mozambique, others have gone seriously awry, such as Angola and Burundi.

While it is important not to overemphasize the importance or influence of political institutions (and particularly of electoral systems) as factors influencing democratic transitions, it is more common when dealing with developing countries that the reverse is true: scholars and policy makers alike have typically given too much attention to social forces and not enough to the careful crafting of appropriate democratic institutions by which those forces can be expressed. As Larry Diamond has argued, “the single most important and urgent factor in the consolidation of democracy is not civil society but political institutionalization.”6 To survive, democracies in developing countries need above all “robust political institutions” such as secure executives and effective legislatures composed of coherent, broadly based parties encouraged by aggregative electoral institutions.7 We thus return to the underlying premise of constitutional engineering as it relates to electoral system design: while it is true that elections are merely one cog in the wheel of a much broader framework of institutional arrangements, sociohistorical pressures, and strategic actor behaviors, at the same time electoral systems are an indispensable and integral part of this broader framework. One electoral system might nurture accommodatory tendencies which already exist, while another may

make it far more rational for ethnic entrepreneurs to base their appeals on exclusionary notions of ethnochauvinism.

What the collective evidence from elections held in divided societies does seem to suggest is that an appropriately crafted electoral system can do some good in nurturing accommodative tendencies, but the implementation of an inappropriate system can do severe harm to the trajectory of conflict resolution and democratization in a plural state (see Reilly, 1997a; Reynolds and Sisk, 1998). Given this, is it possible to outline criteria that one might use to judge the success or failure of any given electoral system design? In light of the multicausal nature of institutions, democracy, and political behavior, it would be foolhardy to say with absolute certainty that a particular electoral system was solely, or even primarily, responsible for a change—for better or worse—in ethnic relations in a divided society. Nevertheless, with the benefit of a holistic view of a nation’s democratization process, it is possible to highlight instances where the electoral system itself appears to have encouraged accommodation, and those where it played a part in exaggerating the incentives for ethnic polarization. We hope that the typologies and analytical tools introduced in this paper as part of a contingent theory of electoral system design may help future research elucidate such electoral system effects.

Our Knowledge to Date

To date, our academic knowledge of electoral systems and their consequences has been predominantly based upon the more generic and abstract study of electoral systems as decision-making rules, structuring games played by faceless “rational actors” in environments which are often devoid of historical, socioeconomic, and cultural context. A comprehensive body of work exists which points to the mathematical effects of various systems on party systems, proportionality, and government formation (see, for example, Farrell, 1997; Grofman and Lijphart, 1986; Lijphart and Grofman, 1984; Lijphart, 1994; Rae, 1967; and Taagepera and Shugart, 1989). This is not to deride those very important works—and the discipline as a whole—rather it reflects the fact that much less work has been carried out on the subject of electoral systems, democratization, and conflict resolution. In addition, the majority of work on electoral systems to date has both exhibited a strong bias toward the study of established democracies in the West, and has been mostly country specific. This paper seeks to give a fillip to the increasingly important and more truly comparative study of how electoral systems can be crafted to improve the lot of divided societies.

Historically, Huntington has identified three periods in which each

contained a “wave” of transitions of states from nondemocracy to multiparty competition (Huntington, 1991). Each wave saw the crafting of new constitutions for a new order, and electoral systems were regularly the most controversial and debated aspect of the new institutions. Huntington’s “first wave” takes in the period from 1828 to 1926 when the United States, Great Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and a number of smaller European states began to evolve degrees of multiparty competition and “democratic” institutional structures. The debates over electoral systems (especially in Scandinavia and continental Europe) during this first wave of democratization mirrored many of the debates that new democracies are experiencing in the 1990s—the perceived tradeoffs between “accountability” and “representativeness,” between a close geographical link between elector and representative and proportionality for parties in parliament (see Carstairs, 1980). Huntington’s second wave encompasses the post-second world war period through the decolonization decades of the 1950s and early 1960s. This wave saw many states either inherit or receive electoral systems designed and promoted by outside powers. West Germany, Austria, Japan, and Korea are examples of such “external imposition” by Allied powers in the postwar period, while virtually all the fleetingly democratic postcolonial nation states of Africa and Asia inherited direct transplants of the electoral and constitutional systems of their colonial masters.

Finally, the “third wave” of democratization, which began with the overthrow of the Salazar dictatorship in Portugal in 1974 and continues on to this day, gives us a wealth of case study material when it comes to assessing electoral system design in new democracies and those societies divided by cultural or social hostilities. In 1997, Reynolds and Reilly found only seven countries (out of 212 independent states and related territories) which did not hold direct elections for their legislatures, and of those 98 were classified as “free” on the basis of political rights and civil liberties in the 1995–1996 Freedom House Freedom in the World (Reynolds and Reilly, 1997). Therefore, we can be confident that a considerable range of comparative material is available for a study of how electoral systems influence democratization and stability in divided societies. This is even more so if we are mindful not to ignore the important lessons of nineteenth-century emerging democracies such as the British dominions (Canada, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand), with their divisions between and within “settler” and “indigenous” groups, or the multiethnic societies of continental Europe (Belgium, Austria-Hungary, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg), which fulfilled many of the classic elements of “plural” or “divided” societies at the turn of the century. In both groups, electoral system design was seen as a means of dealing with divisions and, particularly in the European examples, as a tool of accommodation building between potentially hostile religious or linguistic groups.

DEVELOPING AN ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK FOR A CONTINGENT THEORY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEM DESIGN

Consultants on electoral system design rightly shy away from the “one-size-fits-all” approach of recommending one system for all contexts. Indeed, when asked to identify their “favorite” or “best” system, constitutional experts will say “it depends” and the dependents are more often than not variables such as: What does the society look like? How is it divided? Do ethnic or communal divides dovetail with voting behavior? Do different groups live geographically intermixed or segregated? What is the country’s political history? Is it an established democracy, a transitional democracy, or a redemocratizing state? What are the broader constitutional arrangements that the legislature is working within?

Historically, the process of electoral system design has tended to occur on a fragmented case-by-case basis, which has led to the inevitable and continual reinvention of the wheel because of limited comparative information. In this paper, we seek to develop an analytical framework upon which a contingent theory of electoral system design may be built. When assessing the appropriateness of any given electoral system for a divided society, three variables become particularly salient:

-

knowledge of the nature of societal division is paramount (i.e., the nature of group identity, the intensity of conflict, the nature of the dispute, and the spatial distribution of conflictual groups);

-

the nature of the political system (i.e., the nature of the state, the party system, and the overall constitutional framework); and

-

the process which led to the adoption of the electoral system (i.e., was the system inherited from a colonial power, was it consciously designed, was it externally imposed, or did it emerge through a process of evolution and unintended consequences?).

In the following section we describe these three key variables and then operationalize them in the Conclusion.

Nature of Societal Division

The Nature of Group Identity

As noted earlier, appropriate constitutional design is ultimately contextual and rests on the nuances of a nation’s unique social cleavages. The nature of division within a society is revealed in part by the extent to which ethnicity correlates with party support and voting behavior. And that factor will often determine whether institutional engineering is able to dissipate ethnic conflicts or merely contain them. There are two dimen-

sions to the nature of group identity: one deals with foundations (i.e., whether the society divided along racial, ethnic, ethnonationalistic, religious, regional, linguistic, etc., lines), while the second deals with how rigid and entrenched such divisions are. Scholarship on the latter subject has developed a continuum with the rigidity of received identity (i.e., primordialism) on one side and the malleability of constructed social identities (i.e., constructivist or instrumentalist) on the other (see Shils, 1957; Geertz, 1973; Young, 1976; Anderson, 1991; Newman, 1991; Esman, 1994).

Clearly, if ethnic allegiances are indeed primordial, and therefore rigid, then a specific type of power sharing, based on an electoral system which primarily recognizes and accommodates interests based on ascriptive communal traits rather than individual ideological ones, is needed to manage competing claims for scarce resources. If ethnic identities and voting behaviors are fixed, then there is no space for institutional incentives aimed at promoting accommodatory strategies to work. Nevertheless, while it is true that in almost all multiethnic societies there are indeed correlations between voting behavior and ethnicity, the causation is far more complex. It is far from clear that primordial ethnicity, the knee-jerk reaction to vote for “your group’s party” regardless of other factors, is the chief explanation of these correlations. More often than not ethnicity has become a proxy for other things, a semiartificial construct which has its roots in community but has been twisted out of all recognition. This is what Robert Price calls the antagonistic “politics of communalism”— ethnicity which has been politicized and exploited to serve entrepreneurial ends (1995).

In practice, virtually every example of politicized ethnic conflict exhibits claims based on a combination of both “primordial” historical associations and “instrumentalized” opportunistic adaptations.8 In the case of Sierra Leone, for example, Kandeh (1992) has shown that dominant local elites, masquerading as “cultural politicians,” shaped and mobilized ethnicity to serve their interests. In Uganda, President Museveni has used the “fear of tribalism” as an excuse to avoid multipartism. Nevertheless, in both the colonial and postcolonial “one-party state” eras, strategies to control and carve up the Ugandan state were based upon the hostile mobilization of ethnic and religious identities. Malawi acts as a counterfactual to the primordial ethnicity thesis and offers an example of how political affiliations play out differently when incentive structures are altered. In the multiparty elections of 1994, a history of colonial rule, missionary activity, and Hastings Banda’s “Chewa-ization” of national culture combined together to plant the seeds of conflictual regionalism which both dovetailed with, and cut across, preconceived ethnic boundaries. The south voted for the United Democratic Front of Bakili Muluzi, the Center for the Malawi Congress Party of Banda, and the north for the

Alliance for Democracy led by Chakufwa Chihana. But voting patterns depended more upon region than ethnicity. Kaspin notes that “not only did non-Tumbuka in the north vote for AFORD, and non-Yao in the south vote for the UDF, but non-Tumbuka and non-Yao groups divided by regional borders tended to support the opposition candidates of their own region” (1995:614).9

If ethnic conflict is not predetermined, or is more often a proxy for other interests, then incentives can be laid for other cleavages to emerge as ethnic divides becomes less salient. In South Africa, for example, the rules of the game encouraged parties to appeal across ethnic boundaries. As Price (1995) notes, South Africa has been remarkably free of ethnic conflict in the postapartheid period, bearing in mind its history of repressive racial laws. Challenging conventional wisdom, he argues that “the South African case is important for the contemporary study of ethnicity in politics precisely because it is an ethnically heterogeneous society without significant ethnic conflict.” The election of April 1994 also lent credence to the claim that the inclusive institutional incentives of the interim constitution helped make politicized ethnicity far less salient. All parties (bar the Afrikaner Freedom Front and the National Party in the Western Cape) strived to appeal across ethnic divides, and the African National Congress (ANC), National Party (NP), Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), DP, and PAC presented multiethnic and multiracial lists of parliamentary candidates. In a 1994 postelection survey, Robert Mattes (1995) of the Institute for Democracy in South Africa found only 3 percent of voters claimed to have based their political affiliations on ethnic identity.10

Intensity of Conflict

A second variable in terms of the nature of any given conflict and its susceptibility to electoral engineering is simply the intensity and depth of hostility between the competing groups. It is worth remembering that, although academic and international attention is naturally drawn to extreme cases, most ethnic conflicts do not degenerate into all-out civil war (Fearon and Laitin, 1996). While few societies are entirely free from multiethnic antagonism, most are able to manage to maintain a degree of mutual accommodation sufficient to avoid state collapse. There are numerous examples of quite deeply divided states in which the various groups maintain frosty but essentially civil relations between one another despite a considerable degree of mutual antipathy—such as the relations between Malays, Chinese, and Indians in Malaysia. There are other cases (e.g., Sri Lanka) where what appeared to be a relatively benign interethnic environment and less pronounced racial cleavages nonetheless broke down into violent armed conflict, but where democratic government has none-

theless been the rule more than the exception. And then, of course, there are the cases of utter breakdown in relations and the “ethnic cleansing” of one group by another, typified most recently and horribly by Bosnia.

The significance of these examples is that each of these states is deeply divided, but the different intensity of the conflict means that different electoral “levers” would need to be considered in each case. Malaysia has been able to use a majoritarian electoral system which utilizes a degree of “vote pooling” and power sharing to manage relations between the major ethnic groups—a successful strategy in terms of managing ethnic relations there, but possible only because Chinese voters are prepared, under the right circumstances, to vote for Malay candidates and vice versa. By contrast, under the “open-list” proportional representation (PR) system used for parliamentary elections in Sri Lanka, research has found that Sinhalese voters will, if given the chance, deliberately move Tamil candidates placed in a winnable position on a party list to a lower position—a factor which may well have occurred in South Africa as well, had not the electoral system used been a “closed” list, which allowed major parties such as the ANC and the NP to place ethnic minorities and women high on their party list. But even in Sri Lanka, the electoral system for presidential elections allows Tamils and other minorities to indicate who their least-disliked Sinhalese candidate is—a system which has seen the election of ethnic moderates to the position of president at every election to date (Reilly, 1997b).

Contrast this with a case like Bosnia, where relations between ethnic groups are so deeply hostile that it is almost inconceivable that electors of one group would be prepared to vote for others under any circumstances. There, the 1996 transitional elections were contested overwhelmingly by ethnically based parties, with minimal contact between competing parties, and with any accommodation between groups having to take place after the election—in negotiations between ethnic elites representing the various groups—rather than before. The problem with such an approach is that it assumes that elites themselves are willing to behave moderately to their opponents, when much of the evidence from places like Bosnia tends directly to contradict such an assumption. We will return to this problem, which bedevils elite-centered strategies for conflict management, later in this paper.

The Nature of the Dispute

Electoral system design is not merely contingent upon the basis and intensity of social cleavages but also, to some extent, upon the nature of the dispute, which is manifested from cultural differences. The classic issue of dispute, is the issue of group rights and status in a “multiethnic

democracy,” that is, a system characterized both by democratic decision-making institutions and by the presence of two or more ethnic groups, defined as a group of people who see themselves as a distinct cultural community; who often share a common language, religion, kinship, and/ or physical characteristics (such as skin color); and who tend to harbor negative and hostile feelings toward members of other groups.11 The majority of this paper deals with this fundamental cleavage of ethnicity.

Other types of disputes often dovetail with ethnic ones, however. If the issue that divides groups is resource based, for example, then the way in which the national parliament is elected has particular importance as disputes are managed through central government allocation of resources to various regions and peoples. In this case, an electoral system which facilitated a broadly inclusive parliament might be more successful than one which exaggerated majoritarian tendencies or ethnic, regional, or other cleavages. This requirement would still hold true if the dispute was primarily cultural (i.e., revolved around the protection of minority languages and culturally specific schooling), but other institutional mechanisms, such as cultural autonomy and minority vetoes, would be at least as influential in alleviating conflict. The range of mechanisms available to conflicting parties is thus likely to include questions of parliamentary rules, power-sharing arrangements, language policies, and various forms of devolution and autonomy (see Harris and Reilly, 1998).

Lastly, disputes over territory often require innovative institutional arrangements which go well beyond the positive spins that electoral systems can create. In Spain and Canada, asymmetrical arrangements for, respectively, the Basque and Quebec regions, have been used to try and dampen calls for secession, while federalism has been promoted as an institution of conflict management in countries as diverse as Germany, Nigeria, South Africa, and Switzerland. All of these arrangements have a direct impact upon the choice of an appropriate electoral system. An example is the distinction in federal systems between lower “representative” chambers of parliament and upper “deliberative” ones, which create very different types of demands on politicians and thus require different electoral system choices to work effectively.

Spatial Distribution of Conflictual Groups

A final consideration when looking at different electoral options concerns the spatial distribution of ethnic groups, and particularly their relative size, number, and degree of geographic concentration or dispersion. For one thing, it is often the case that the geographic distribution of conflicting groups is also related to the intensity of conflict between them. The frequent intergroup contact facilitated by geographical intermixture

may increase the levels of mutual hostility, but it is also likely to act as a oderating force against the most extreme manifestations of ethnic conflict.12 Familiarity may breed contempt, but it also usually breeds a certain degree of acceptance. Intermixed groups are thus less likely to be in a state of all-out civil war than those that are territorially separated from one another.

Furthermore, intermixing gives rise to different ethnic agendas and desires. Territorial claims and self-determination rallying cries are more difficult to invoke when groups are widely dispersed and intermixed with each other. In such situations, group mobilization around issues such as civil or group rights and economic access is likely to be more prevalent.13 Conversely, however, territorial separation is sometimes the only way to manage the most extreme types of ethnic conflict, which usually involves consideration of some type of formal territorial devolution of power or autonomy. In the extreme case of “ethnic cleansing” in Bosnia, areas which previously featured highly intermixed populations of Serbs, Croats, and Muslims are now predominantly monoethnic.

Another scenario is where the distribution of ethnic groups is such that some types of electoral system are naturally precluded. This is a function not of group size so much as the geographic concentration or dispersion of different communities. Any electoral strategy for conflict management needs to be tailored to the realities of political geography. Territorial prescriptions for federalism or other types of devolution of power will usually be a prominent concern, as will issues of group autonomy. Indigenous and/or tribal groups tend to display a particularly strong tendency toward geographical concentration. African minorities, for example, have been found to be more highly concentrated in single contiguous geographical areas than minorities in other regions, which means that many electoral constituencies and informal local power bases will be controlled by a single ethnopolitical group (Scarritt, 1993). This has considerable implications for electoral engineers: it means that any system of election that relies on single-member electoral districts will likely produce “ethnic fiefdoms” at the local level. Minority representation and/or power sharing under these conditions would probably require some form of multimember district system and proportional representation.

Contrast this with the highly intermixed patterns of ethnic settlement found as a result of colonial settlement or labor importation and the vast Chinese and Indian diasporas found in some Asia-Pacific (e.g., Singapore, Fiji, Malaysia) and Caribbean (Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago) countries, in which members of various ethnic groups tend to be much more widely intermixed and, consequently, have more day-to-day contact. Here, ethnic identities are often mitigated by other cross-cutting cleavages, and

even small single-member districts are likely to be ethnically heterogeneous, so that electoral systems which encourage parties to seek the support of different ethnic groups may well work to break down interethnic antagonisms and promote the development of broad, multiethnic parties. This situation requires a very different set of electoral procedures.

A final type of social structure involves extreme ethnic multiplicity, typically based upon the presence of many small, competing tribal groups—an unusual composition in Western states, but common in some areas of central Africa and the South Pacific—which typically requires strong local representation to function effectively. In the extreme case of Papua New Guinea, for example, there are several thousand competing clan groups speaking over 800 distinct languages (see Reilly, 1998a). Any attempt at proportional representation in such a case would be almost impossible, as it would require a parliament of several thousand members (and, because parties are either weak or nonexistent in almost all such cases, the usual party-based systems of proportional representation would be particularly inappropriate). This dramatically curtails the range of options available to electoral engineers.

Nature of Political System

Institutional prescriptions for electoral engineering also need to be mindful of the different political dynamics that distinguish transitional democracies from established ones. Transitional democracies, particularly those moving from a deep-rooted conflict situation, typically have a greater need for inclusiveness and a lower threshold for the robust rhetoric of adversarial politics than their established counterparts. Similarly, the stable political environments of most Western countries, where two or three main parties can often reasonably expect regular periods in office via alternation of power or shifting governing coalitions, are very different from the type of zero-sum politics which so often characterizes divided societies. This is one of the reasons that “winner-take-all” electoral systems have so often been identified as a contributor to the breakdown of democracy in the developing world: such systems tend to lock out minorities from parliamentary representation and, in situations of ethnically based parties, can easily lead to the total dominance of one ethnic group over all others. Democracy, under these circumstances, can quickly become a situation of permanent inclusion and exclusion, a zero-sum game, with frightening results.

Electoral laws also affect the size and development of political parties. At least since Duverger, the conventional wisdom among electoral scholars has been that majoritarian electoral rules encourage the formation of a two-party system (and, by extension, one-party government),

while proportional representation leads to a multiparty system (and coalition government). While there remains general agreement that majority systems tend to restrict the range of legislative representation and PR systems encourage it, the conventional wisdom of a causal relationship between an electoral system and a party system is increasingly looking out of date. In recent years, first-past-the-post (FPTP) has facilitated the fragmentation of the party system in established democracies such as Canada and India, while PR has seen the election of what look likely to be dominant single-party regimes in Namibia, South Africa, and elsewhere.

Just as electoral systems affect the formation of party systems, so party systems themselves have a major impact upon the shape of electoral laws. It is one of the basic precepts of political science that politicians and parties will make choices about institutions such as electoral systems that they think will benefit themselves. Different types of party systems will thus tend to produce different electoral system choices. The best-known example of this is the adoption of PR in continental Europe in the early 1900s. The expansion of the franchise and the rise of powerful new social forces, such as the labor movement, prompted the adoption of systems of PR which would both reflect and restrain these changes in society (Rokkan, 1970). More recent transitions have underlined this “rational actor” model of electoral system choice. Thus, threatened incumbent regimes in Ukraine and Chile adopted systems which they thought would maximize their electoral prospects: a two-round runoff system which overrepresents the former communists in the Ukraine (Birch, 1997), and a unusual form of PR in two-member districts which was calculated to overrepresent the second-place party in Chile (Barczak, 1997). An interesting exception which proves the validity of this rule was the ANC’s support for a PR system for South Africa’s first postapartheid elections. Retention of the existing FPTP system would almost undoubtedly have seen the overrepresentation of the ANC, as the most popular party, but it would also have led to problems of minority exclusion and uncertainty. The ANC made a rational decision that its long-term interest would be better served by a system which enabled it to control its nominated candidates and bring possibly destabilizing electoral elements “into the tent” rather than giving them a reason to attack the system itself.

Lastly, the efficacy of electoral system design needs to be seen in juxtaposition to the broader constitutional framework of the state. This paper concentrates on elections that constitute legislatures. The impact of the electoral system on the membership and dynamics of that body will always be significant, but the electoral system’s impact upon political accommodation and democratization more generally is tied to the amount of power held by the legislature and that body’s relationship to other

political institutions. The importance of electoral system engineering is heightened in centralized, unicameral parliamentary systems, and is maximized when the legislature is then constitutionally obliged to produce an oversized executive cabinet of national unity drawn from all significant parties that gain parliamentary representation.

Similarly, the efficacy of electoral system design is incrementally diminished as power is eroded away from the parliament. Thus, constitutional structures which diffuse and separate powers will distract attention from elections to the legislature and will require the constitutional designer to focus on the interrelationships between executives and legislatures, between upper and lower houses of parliament, and between national and regional and local governments. This is not to diminish the importance of electoral systems for these other institutions (for example, presidencies or federal legislatures); rather, it highlights the fact that constitutional engineering becomes increasingly complex as power is devolved away from the center. Each of the following institutional components of the state may fragment the focal points of political power and thus diminish the significance of electoral system design on the overall political climate: (1) a directly elected president, (2) a bicameral parliament with a balance of power between the two houses, and (3) a degree of federalism and/or regional asymmetrical arrangements. Similarly, greater centralization of power in the hands of one figure, such as a president, raises the electoral stakes. Thus, some analysts have attributed the failure of democracy in Angola in 1992 to the combination of a strong presidential system with a run-off electoral system, which pitted the leaders of two competing armed factions in a head-to-head struggle that only one could win, thus almost guaranteeing that the “loser” would resume hostilities (Reid, 1993).

THE WORLD OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS

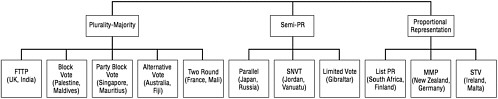

There are countless electoral system variations, but essentially they can be split into 11 main systems which fall into three broad families. The most common way to look at electoral systems is to group them by how closely they translate national votes won into parliamentary seats won; that is, how proportional they are. To do this, one needs to look at both the vote-seat relationship and the level of wasted votes.14 If we take the proportionality principle into account, along with some other considerations such as how many members are elected from each district and how many votes the elector has, we are left with the family structure illustrated in Figure 11.1.

Plurality-Majority Systems

These comprise three plurality systems—first past the post, the block vote, and the party block vote—and two majority systems, the alternative vote and the two-round system.

-

First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) is the world’s most commonly used system. Contests are held in single-member districts, and the winner is the candidate with the most votes, but not necessarily an absolute majority of the votes. FPTP is supported primarily on the grounds of simplicity, and its tendency to produce representatives beholden to defined geographic areas. Countries that use this system include the United Kingdom, the United States, India, Canada, and most countries that were once part of the British Empire.

-

The Block Vote (BV) is the application of FPTP in multi- rather than single-member districts. Voters have as many votes as there are seats to be filled, and the highest-polling candidates fill the positions regardless of the percentage of the vote they actually achieve. This system is used in some parts of Asia and the Middle East.

-

The Party Block Vote (PBV) operates in multimember districts and requires voters to choose between party lists of candidates rather than individuals. The party which wins the most votes takes all the seats in the district, and its entire list of candidates is duly elected. Variations on this system can be used to balance ethnic representation, as is the case in Singapore (discussed in more detail later).

-

Under the Alternative Vote (AV) system, electors rank the candidates in order of choice, marking a “1” for their favorite candidate, “2” for their second choice, “3” for their third choice, and so on. The system thus enables voters to express their preferences between candidates, rather than simply their first choice. If no candidate has over 50 percent of first preferences, lower-order preference votes are transferred until a majority winner emerges. This system is used in Australia and some other South Pacific countries.

-

The Two-Round System (TRS) has two rounds of voting, often a week or a fortnight apart. The first round is the same as a normal FPTP election. If a candidate receives an absolute majority of the vote, then he or she is elected outright, with no need for a second ballot. If, however, no candidate has received an absolute majority, then a second round of voting is conducted, and the winner of this round is declared elected. This system is widely used in France, former French colonies, and some parts of the former Soviet Union.

Semiproportional Systems

Semi-PR systems are those which inherently translate votes cast into seats won in a way that falls somewhere in between the proportionality of PR systems and the majoritarianism of plurality-majority systems. The three semi-PR electoral systems used for legislative elections are the single nontransferable vote (SNTV), parallel (or mixed) systems, and the limited vote (LV).

-

In SNTV Systems, each elector has one vote, but there are several seats in the district to be filled, and the candidates with the highest number of votes fill these positions. This means that in a four-member district, for example, one would on average need only just over 20 percent of the vote to be elected. This system is used today only in Jordan and Vanuatu, but is most often associated with Japan, which used SNTV until 1993.

-

Parallel Systems use both PR lists and single-member districts running side by side (hence the term parallel). Part of the parliament is elected by proportional representation, part by some type of plurality or majority method. Parallel systems have been widely adopted by new democracies in the 1990s, perhaps because, on the face of it, they appear to combine the benefits of PR lists with single-member district representation. Today, parallel systems are used in Russia, Japan, South Korea, Thailand, and the Philippines, among others.

-

The Limited Vote (LV), used in Gibraltar, the Spanish upper house, and in many U.S. local government elections, usually gives voters one less vote than there are seats to be filled. In its Spanish and U.K. manifestations, the limited vote shared many of the properties of the block vote, but Lijphart, Pintor, and Stone (1986) argue that because it facilitates minority representation it should be referred to as a Semiproportional system.

Proportional Representation Systems

All proportional representation (PR) systems aim to reduce the disparity between a party’s share of national votes and its share of parliamentary seats. For example, if a major party wins 40 percent of the votes, it should also win around 40 percent of the seats, and a minor party with 10 percent of the votes should similarly gain 10 percent of the seats. For many new democracies, particularly those that face deep divisions, the inclusion of all significant groups in the parliament can be an important condition for democratic consolidation. Outcomes based on consensus building and power sharing usually include a PR system.

Criticisms of PR are twofold: that it gives rise to coalition governments, with disadvantages such as party system fragmentation and government instability, and that PR produces a weak linkage between a rep-

resentative and her or his geographical electorate. And since voters are expected to vote for parties rather than individuals or groups of individuals, it is a difficult system to operate in societies that have embryonic or loose party structures.

-

List PR Systems are the most common type of PR. Most forms of list PR are held in large, multimember districts that maximize proportionality. List PR requires each party to present a list of candidates to the electorate. Electors vote for a party rather than a candidate, and parties receive seats in proportion to their overall share of the national vote. Winning candidates are taken from the lists in order of their respective positions. This system is widely used in continental Europe, Latin America, and southern Africa.

-

Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) Systems, as used in Germany, New Zealand, Bolivia, Italy, Mexico, Venezuela, and Hungary, attempt to combine the positive attributes of both majoritarian and PR electoral systems. A proportion of the parliament (roughly half in the cases of Germany, New Zealand, Bolivia, and Venezuela) is elected by plurality-majority methods, usually from single-member districts, while the remainder is constituted by PR lists. The PR seats are used to compensate for any disproportionality produced by the district seat results. Single-member districts also ensure that voters have some geographical representation.

-

The Single Transferable Vote (STV) uses multimember districts, where voters rank candidates in order of preference on the ballot paper in the same manner as AV. After all first-preference votes are tallied, a “quota” of votes is established, which a candidate must achieve to be elected. Any candidate who has more first preferences than the quota is immediately elected. If no one has achieved the quota, the candidate with the lowest number of first preferences is eliminated, and their second preferences are redistributed among remaining candidates. And the surplus votes of elected candidates (i.e., those votes above the quota) are redistributed according to the second preferences on the ballot papers until all seats for the constituency are filled. This system is well established in Ireland and Malta.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE PROCESS WHICH LED TO THE CHOICE OF ELECTORAL SYSTEM

Although the choice of electoral system is one of the most important institutional decisions for any democracy, it is relatively unusual in historical terms for electoral systems to be consciously and deliberately chosen. Often, the choice of electoral system is essentially accidental: the result of an unusual combination of circumstances, of a passing trend, or of a quirk of history. The impacts of colonialism and the effects of influen-

tial neighbors are often especially strong. Yet in almost all cases, a particular electoral system choice has a profound effect on the future political life of the country concerned. Electoral systems, once chosen, tend to remain fairly constant, as political interests quickly congeal around and respond to the incentives for election presented by the system.

If it is rare that electoral systems are deliberately chosen, it is rarer still that they are carefully designed for the particular historical and social conditions present in a given country. This is particularly the case for new democracies. Any new democracy must choose (or inherit) an electoral system to elect its parliament. But such decisions are often taken within one of two circumstances. Either political actors lack basic knowledge and information, and the choices and consequences of different electoral systems are not fully recognized or, conversely, political actors do have knowledge of electoral system consequences and thus promote designs which they perceive will maximize their own advantage (see Taagepera, 1998). In both of these scenarios, the choices that are made are sometimes not the best ones for the long-term political health of the country concerned; at times, they can have disastrous consequences for a country’s democratic prospects.

The way in which an electoral system is chosen can thus be as important and enlightening as the choice itself. There are four ways in which most electoral systems are adopted: via colonial inheritance, through conscious design, by external imposition, and by accident. We will now deal with each of these processes in turn.

Colonial Inheritance

Inheriting an electoral system from colonial times is perhaps the most common way through which democratizing societies come to use a particular system. For example, out of 53 former British colonies and members of the Commonwealth of Nations, a full 37 (or 70 percent) use classic first-past-the-post systems inherited from Westminster. Eleven of the 27 Francophone territories use the French two-round system, while the majority of the remaining 16 countries use list PR, a system used by the French on and off since 1945 for parliamentary elections, and widely for municipal elections. Fifteen out of the 17 Spanish-speaking countries and territories use PR (as does Spain), while Guatemala and Ecuador use list PR as part of their parallel systems. Finally, all six Lusophone countries use list PR, as in Portugal. This pattern even extends to the former Soviet Republics of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS): eight of these states use the two-round system in some form (see Reynolds and Reilly, 1997).

Colonial inheritance of an electoral system is perhaps the least likely

way to ensure that the institution is appropriate to a country’s needs, as the begetting colonial power was usually very different socially and culturally from the society colonized. And even where the colonizer sought to stamp much of its political ethos on the occupied land, it rarely succeeded in obliterating indigenous power relations and traditional modes of political discourse. It is therefore not surprising that the colonial inheritance of Westminster systems has been cited as an impediment to stability in a number of developing countries, for example, in the Caribbean (Lewis, 1965), Nigeria (see Diamond, 1995, and Laitin, 1986), and Malawi (see Reynolds, 1995). Similarly, Mali’s use of the French two-round system has been questioned by Vengroff (1994), Indonesia’s Dutch-inherited list PR system has been cited as restricting that country’s political development (MacBeth, 1998), and Jordan and Palestine’s use of the British-inspired block vote has also led to problems (Reynolds and Elklit, 1997).

Conscious Design

The deliberate design of electoral systems to achieve certain preconceived outcomes is not a new phenomenon, although its incidence has waxed and waned over this century. Enthusiasm for electoral engineering appears to correspond, logically enough, to successive “waves” of democratization (Huntington, 1991). Huntington’s first wave, from 1828 until 1926, saw several examples of deliberate electoral engineering that are now well-established electoral institutions. The alternative vote system introduced for federal elections in Australia in 1918, for example, was intended to mitigate the problems of conservative forces “splitting” their vote in the face of a rising Labor Party. It did exactly that (Reilly, 1997b). At Irish independence in 1922, both the indigenous political elite and the departing British favored the single transferable vote due to its inherent fairness and protection of Protestant and Unionist minorities (Gallagher, 1997). The adoption of list PR systems in continental Europe occurred first in the most culturally diverse societies, such as Belgium and Switzerland, as a means of ensuring balanced interethnic representation (Rokkan, 1970). All of these cases represented examples of conscious institutional engineering utilizing what were, at the time, new electoral systems in fledgling and divided democracies.

The short second wave of democratization in the decolonization decades after the second world war also saw the electoral system used as a lever for influencing the future politics of new democracies. Most of the second wave, however, featured less in the way of deliberate design and more in the way of colonial transfer. Thus, ethnically plural states in Africa and fragile independent nations in Asia inherited British first-past-

the-post or French two-round systems; and in nearly all cases these inappropriate models, transplanted directly from colonial Western powers, contributed to an early “reverse wave” of democracy.

The “third wave” of democracy has seen a new appreciation of the necessity for and utility of well-crafted electoral systems as a key constitutional choice for new democracies. In recent years, transitions to democracy in Hungary, Bolivia, South Africa, Korea, Taiwan, Fiji, and elsewhere have all been accompanied by extensive discussion and debate about the merits of particular electoral system designs. A parallel process has taken place in established democracies, with Italy, Japan, and New Zealand all changing their electoral systems in the 1990s. In most cases, these choices are based on negotiations between political elites, but in some countries (e.g., Italy and New Zealand) public plebiscites have been held to determine the voters’ choice on this most fundamental of electoral questions.

External Imposition

A small number of electoral systems were more consciously designed and imposed on nation states by external powers. Two of the most vivid examples of this phenomenon occurred in West Germany after the second world war, and in Namibia in the late 1980s.

In postwar Germany, both the departing British forces and the German parties were anxious to introduce a system which would avoid the damaging party proliferation and destabilization of the Weimar years,15 and to incorporate the Anglo tradition of constituency representation because of unease with the 1919–1933 closed-list electoral system, which denied voters a choice between candidates as well as parties (Farrell, 1997:87–88). During 1946, elections in the French and American zones of occupation were held under the previous Weimar electoral system. But in the British zone a compromise was adopted which allowed electors to vote for constituency members with a number of list PR seats reserved to compensate for any disproportionality that arose from the districts. Thus, the mixed-member proportional (MMP) system, which has since been emulated by a number of other countries, was born. This mixed system was adopted for all parliamentary elections in 1949, but it was not until 1953 that two separate votes were introduced, one for the constituency member, and another based on the Länder, which ultimately determined the party composition of the Bundestag. The imposition of a 5 percent national threshold for party list representation helped focus the party system around three major groupings after 1949 (the Social Democrats, Christian Democrats, and Free Democrats), although in all 12 parties gained representation in those first postwar national elections.

The rationale for a national list PR system in Namibia came initially from the United Nations, which urged as early as 1982 that any future nonracial electoral system ensure that political parties managing to gain substantial support in the election be rewarded with fair representation. The option of discarding the incumbent first-past-the-post electoral system (the whites-only system operating in what was the colony of South West Africa) and moving to PR was proposed by Pik Botha, then South African foreign minister. South Africa had previously, but unsuccessfully, pressed for separate voters’ rolls (à la Zimbabwe 1980–1985), which would have ensured the overrepresentation of whites in the new Constituent Assembly. After expressions of unease that South Africa was promoting PR solely in order to fractionalize the assembly, the UN Institute for Namibia advised all political parties interested in a stable independence government “to reject any PR system that tends to fractionalize party representation” (see Cliffe et al., 1994:116). But this advice remained unheeded, and the option of a threshold for representation (one of the chief mechanisms for reducing the number of parties in a list PR system) was never put forward by the UN or made an issue by any of the political parties. For the first elections in 1989, the South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO) expressed a preference for keeping the single-member district system, no doubt reasonably expecting (as the dominant party) to be advantaged by such winner-take-all constituencies. However, when the Constituent Assembly met for the first time in November 1989, and each parliamentary party presented its draft constitution, SWAPO gave in on the issue of PR—apparently as a concession to the minority parties for which they hoped to gain reciprocal concessions on matters of more importance.

Accidental Adoption/Evolution

Although this paper concentrates on the possibilities of deliberate “electoral engineering,” it is worth remembering that most electoral systems are not deliberately chosen. Often, choices are made through a kaleidoscope of accidents and miscommunications leading to a multitude of unintended consequences.

Accidental choices are not necessarily poor ones; in fact, sometimes they can be surprisingly appropriate. One example of this was the highly ethnically fragmented democracy of Papua New Guinea, which inherited the alternative vote (see below) from its colonial master, Australia, for its first three elections in the 1960s and 1970s. Because this system required voters to list candidates preferentially on the ballot paper, elections encouraged a spectrum of alliances and vote trading between competing candidates and different communal groups, with candidates attempting to win not just first preferences but second and third preference votes as

well. This led to cooperative campaigning tactics, moderate positions, and the early development of political parties. When this system was changed, political behavior became more exclusionary and less accommodatory, and the nascent party system quickly unraveled (Reilly, 1997a).

With the benefit of hindsight, Papua New Guinea thus appears to have been the fortuitous recipient of a possibly uniquely appropriate electoral system for its social structure. Most accidental or evolutionary choices are, however, more likely to lead to less fortuitous unintended consequences— particularly for the actors who designed them. For example, when Jordan reformed its electoral system in 1993, on the personal initiative of King Hussein, it had the effect of increasing minority representation but also facilitating the election of Islamic fundamentalists to the legislature (Reynolds and Elklit, 1997). Many fledgling democracies in the 1950s and 1960s adopted copies of the British system, despite consistent misgivings from Westminster that it was “of doubtful value as an export to tropical colonies, to primitive societies in Africa and to complex societies in India.”16 The sorry history of many such choices has underlined the importance of designing electoral and constitutional rules for the specific conditions of the country at hand, rather than blithely assuming that the same “off-the-shelf” constitutional design will work identically in different social, political, and economic circumstances.

ELECTORAL SYSTEMS AND CONFLICT MANAGEMENT

The comparative experience suggests that four specific systems are particularly suitable for divided societies. These are usually recommended as part of overall constitutional engineering packages, in which the electoral system is one element. Some constitutional engineering packages emphasize inclusiveness and proportionality; others emphasize moderation and accommodation. The four major choices in this regard are (1) consociationalism (based, in part, on list proportional representation); (2) centripetalism (based, in part, on the vote-pooling potential of the alternative vote); (3) integrative consensualism (based, in part, on the single transferable vote), and (4) a construct not previously mentioned, which we call explicitism, which explicitly recognizes communal groups and gives them institutional representation, which in theory can be based on almost any electoral system, but in practice is usually based on the block vote (e.g., in Mauritius, Lebanon, and Singapore).

Consociationalism

One of the most discussed prescriptions for plural (segmented) societies remains that of consociationalism, a term first used by Althusius and

rescued from obscurity by Lijphart in the late 1960s. Consociationalism entails a power-sharing agreement within government, brokered between clearly defined segments of society which may be joined by citizenship but divided by ethnicity, religion, and language. Examples of consociational societies include Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria, and Switzerland. Cyprus and Lebanon are cited as countries which had, but no longer have, a consociational ethos (Lijphart, 1977). The mechanics of consociationalism can be distilled into four basic elements which must be present to make the constitution worthy of the consociational name. They are: (1) executive power sharing among the representatives of all significant groups (a grand coalition in the cabinet); (2) a high degree of internal autonomy for groups that wish to have it (constitutionally entrenched segmental autonomy); (3) proportional representation (through list PR) and proportional allocation of civil service positions and public funds (proportionality); and (4) a minority veto on the most vital issues (a mutual veto for parties in the executive) (Lijphart, 1977:25).

These arrangements encourage government to become an inclu-sive multiethnic coalition, in contrast to the adversarial nature of a Westminster winner-take-all democracy. Consociationalism rests on the premise that in bitterly divided societies the stakes are too high for politics to be conducted as a zero-sum game. Also, the risks of governmental collapse and state instability are too great for parties to view the executive branch of government as a prize to be won or lost. The fact that grand coalitions exist in Westminster democracies at times of particular crisis further supports the consociational claim.17

Arguments in Favor

Consociationalism is particularly reliant on a PR electoral system to provide a broadly representative legislature upon which the other tenets of minority security can be based. Lijphart clearly expresses a preference for using party list forms of PR rather than STV, or by implication open-list PR systems and mixed systems which give the voter multiple votes. In a discussion of the proposals for South Africa he noted that STV might indeed be superior for reasonably homogeneous societies, but “for plural societies list PR is clearly the better method” because it: (1) allows for higher district magnitude—thus increasing proportionality, (2) is less vulnerable to gerrymandering, and (3) is simpler (than STV) for the voters and vote counters and thus will be less open to suspicion.18

In many respects, the strongest arguments for PR derive from the way in which the system avoids the anomalous results of plurality-majority systems and facilitates a more representative legislature. For many new democracies, particularly those which face deep societal divisions,

the inclusion of all significant groups in the parliament can be a near-essential condition for democratic consolidation. Failing to ensure that both minorities and majorities have a stake in these nascent political systems can have catastrophic consequences. Recent transitional elections in Chile (1989), Namibia (1989), Nicaragua (1990), Cambodia (1993), South Africa (1994), Mozambique (1994), and Bosnia (1996) all used a form of regional or national list PR for their founding elections, and some scholars have identified the choice of a proportional rather than a majoritarian system as being a key component of their successful transitions to democracy (Lijphart, 1977; Reynolds, 1995). By bringing minorities into the process and fairly representing all significant political parties in the new legislature, regardless of the extent or distribution of their support base, PR has been seen as being an integral element of creating an inclusive and legitimate postauthoritarian regime.

More specifically, PR systems in general are praised because of the way in which they: (1) faithfully translate votes cast into seats won, and thus avoid some of the more destabilizing and “unfair” results thrown up by plurality-majority electoral systems; (2) give rise to very few wasted votes; (3) facilitate minority parties’ access to representation; (4) encourage parties to present inclusive and socially diverse lists of candidates; (5) make it more likely that the representatives of minority cultures/ groups are elected;19 (6) make it more likely that women are elected;20 (7) restrict the growth of “regional fiefdoms”;21 and (8) make power sharing between parties and interest groups more visible.

Arguments Against

While large-scale PR appears to be an effective instrument for smoothing the path of democratic transition, it may be less effective at promoting democratic consolidation. Developing countries in particular which have made the transition to democracy under list PR rules have increasingly found that the large, multimember districts required to achieve proportional results also create considerable difficulties in terms of political accountability and responsiveness between elected politicians and voters. Democratic consolidation requires the establishment of a meaningful relationship between the citizen and the state, and many new democracies—particularly those in agrarian societies (Barkan, 1995)—have much higher demands for constituency service at the local level than they do for representation of all shades of ideological opinion in the legislature. It is therefore increasingly being argued in South Africa, Indonesia, Cambodia, and elsewhere that the choice of a permanent electoral system should

encourage a high degree of geographic accountability, by having members of parliament who represent small, territorially defined districts and servicing the needs of their constituency, in order to establish a meaningful relationship between the rulers and the ruled. While this does not preclude all PR systems—there are a number of ways of combining single-member districts with proportional outcomes—it does rule out the national list PR systems often favored by consociationalists.