3

Defining Moment: The Threat and Use of Force in American Foreign Policy Since 1989

Barry M.Blechman and Tamara Cofman Wittes

The use of military force has been a difficult subject for American leaders for three decades. Ever since the failure of American policy and military power in Vietnam, it has been hard for U.S. policy makers to gain domestic support for the use of force as an instrument of statecraft. U.S. military power has been exercised throughout this 30-year period, but both threats of its use and the actual conduct of military operations have usually been controversial, turned to reluctantly, and marked by significant failures as well as successes. The American armed forces are large, superbly trained, fully prepared, and technologically advanced. Since the demise of the Soviet Union, U.S. forces are without question the most powerful, by far, on the face of the earth. Their competence, lethality, and global reach have been demonstrated time and again. Yet with rare exceptions, U.S. policy makers have found it difficult to achieve their objectives by threats alone. Often, they have had to use force, even if only in limited ways, to add strength to the words of diplomats. And, at more times than is desirable, the failures of threats and limited demonstrative uses of military power have confronted U.S. presidents with difficult choices between retreat and “all-out” military actions intended to achieve objectives by the force of arms alone.

In the 1980s most U.S. military leaders and many politicians and policy makers drew a strong conclusion from the failure of U.S. policy in Vietnam. This viewpoint was spelled out most clearly by then Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger in 1984: force should only be used as a last resort, he stated, to protect vital American interests, and with a commitment to win. Threats of force should not be used as part of diplomacy.

They should be used only when diplomacy fails and, even then, only when the objective is clear and attracts the support of the American public and the Congress.1

General Colin Powell, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was and remains a proponent of what was called the Weinberger doctrine. “Threats of military force will work,” he says, “only when U.S. leaders actually have decided that they are prepared to use force.” In the absence of such resolution, U.S. threats lack credibility because of the transparency of the American policy-making process. For this reason “the threat and use of force must be a last resort and must be used decisively.”2 Powell (1992a, 1992b) has argued that any use of force by the United States should accomplish U.S. objectives quickly while minimizing the risks to U.S. soldiers.

Other U.S. policy makers have taken a more traditional geopolitical view, believing that the U.S. failure in Vietnam needs to be understood on its own terms. Regardless of what was or was not achieved in Southeast Asia in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the United States, they believe, can and should continue to threaten and to use limited military force in support of diplomacy, to achieve limited ends without resorting to all-out contests of arms. In the words of then Secretary of State George Shultz in December 1984, “Diplomacy not backed by strength will always be ineffectual at best, dangerous at worst” (Shultz, 1985). Moreover, Shultz insisted, a use of force need not enjoy public support when first announced; it will acquire that support if the action is consonant with America’s interests and moral values. In 1992 Les Aspin, then chairman of the House Armed Services Committee and later secretary of defense, branded the Weinberger doctrine an “all-or-nothing” approach. He asserted that the United States should be willing to use limited force for limited objectives and that it could pull back from such limited engagements without risk.3 From this perspective, force should be used earlier in a crisis, rather than later, and need not be displayed in decisive quantities. The “limited objectives” school describes the threat of force as an important and relatively inexpensive adjunct to American diplomatic suasion.

As the Soviet Union disintegrated and the Cold War came to an end, this debate began to wane. U.S. policy makers began to wrestle with an array of problems that were individually less severe than the threat posed by the USSR but collectively no less vexing. The military situation changed drastically as well. U.S. military power reigned supreme, and the risk that a limited military intervention in a third nation could escalate into a global confrontation quickly faded. During both the Bush and first Clinton administrations, it became increasingly evident not only that there were many situations in which limited applications of force seemed help-

ful but that in the complicated post-Cold War world, opportunities for the pure application of Secretary Weinberger’s maxims were rare. During this eight-year period, numerous challenges to American interests emerged that were too intractable for diplomatic solutions, that resisted cooperative multilateral approaches, and that were immune not only to sweet reason but to positive blandishments of any sort. Unencumbered by Cold War fears of sparking a confrontation with the powerful Soviet Union, American policy makers turned frequently to threats and the use of military power to deal with these situations, sometimes in ways that conformed to the Weinberger guidelines but more often suggesting that, rightly or wrongly, the press of world events drives policy makers inevitably toward Secretary Shultz’s prescriptions for limited uses of force in support of diplomacy.

The United States sometimes succeeded in these ventures and sometimes failed. Success rarely came easily, however; more often, the United States had to go to great lengths to persuade adversaries to yield to its will. Even leaders of seemingly hapless nations, or of factions within devastated countries, proved surprisingly resistant to American threats. Often, U.S. leaders had to make good on threats by exercising U.S. military power. These further steps usually worked, but even when the United States conducted military operations in support of its post-Cold War policies the results were not always as clean and easy, or their consequences as far reaching, as decision makers had hoped. Given the overwhelming superiority of U.S. military power during this period, these results are hard to understand.

Indeed, even the greatest military success of the U.S. armed forces in the post-Cold War period—the expulsion of the Iraqi occupation army from Kuwait in 1991—became necessary because U.S. diplomacy, including powerful threats of force, failed. Despite the most amazing demonstration of U.S. military capabilities and willingness to utilize force if necessary to expel the Iraqi military from Kuwait, despite the movement of one-half million U.S. soldiers, sailors, and air men and women to the region, the call-up of U.S. reserve forces, the forging of a global military alliance, even the conduct of a devastating air campaign against the Iraqi occupation army and against strategic targets throughout Iraq itself, Saddam Hussein refused to comply with U.S. demands and his troops had to be expelled by force of arms. The United States was not able to accomplish its goals through threats alone. The Iraqi leader either disbelieved the U.S. threats, discounted U.S. military capabilities, or was willing to withstand defeat in Kuwait in pursuit of grander designs.

Why was this the case? Why has it been so difficult for the United States to realize its objectives through threats of using military force alone? Why have U.S. military threats not had greater impact in the post-Cold

War period, and why have limited uses of force, in support of diplomacy and in pursuit of political aims, not been able to accomplish U.S. goals more often? Is this situation changing as it becomes indisputably clear that the United States is the only remaining military superpower? Or have history and circumstance made U.S. military superiority an asset of only narrow utility in advancing the nation’s interests through diplomacy?

To answer these questions, we examined all the cases during the Bush and first Clinton administrations in which the United States utilized its armed forces demonstratively in support of political objectives in specific situations. There are eight such cases, several of which include multiple uses of force. In two of the cases, Iraq and Bosnia, threats or uses of force became enduring elements in defining the limits of the relationship between the United States and its adversary.

Actually, the U.S. armed forces have been used demonstratively in support of diplomatic objectives in literally more than a thousand incidents during this period, ranging from major humanitarian operations to joint exercises with the armed forces of friendly nations to minor logistical operations in support of the United Nations (UN) or other multinational or national organizations. Moreover, the deployment and operations of U.S. forces in Europe, and in Southwest and East Asia on a continuing basis throughout the period, are intended to support U.S. foreign policy by deterring foreign leaders from pursuing hostile aims and by reassuring friends and allies. In some cases the presence of these forces, combined with the words of American leaders, may have been sufficient to deter unwanted initiatives. The presence of U.S. troops in South Korea, for example, is believed to deter a North Korean attack. We did not look at such cases of continuing military support of diplomacy in which “dogs may not have barked.”4 Instead, we looked only at the handful of specific incidents in which U.S. armed forces were used deliberately and actively to threaten or to conduct limited military operations in support of American policy objectives in specific situations.5

We did not examine such military threats prior to the Bush administration because, as noted above, the Cold War placed significant constraints on U.S. uses of force. We believe that the demise of the USSR altered the global political and military environments so fundamentally as to make prior incidents irrelevant to understanding the effectiveness of contemporary military threats. The puzzle we seek to explain is the frequent inability of the United States to achieve its objectives through threats and limited uses of military power despite the political and military dominance it has enjoyed since 1989.

We supplemented published information about the cases we considered with interviews with key U.S. policy makers during this period,

including individuals who served in high positions in the Pentagon and at the State Department. At times these individuals are quoted directly. More often, their perspectives provide background and detail in the accounts of the incidents.6

We have concluded that the U.S. experience in Vietnam and subsequent incidents during both the Carter and first Reagan administrations left a heavy burden on future American policy makers. There is a generation of political leaders throughout the world whose basic perception of U.S. military power and political will is one of weakness, who enter any situation with a fundamental belief that the United States can be defeated or driven away. This point of view was expressed explicitly and concisely by Mohamed Farah Aideed, leader of a key Somali faction, to Ambassador Robert Oakley, U.S. special envoy to Somalia, during the disastrous U.S. involvement there in 1993–1995: “We have studied Vietnam and Lebanon and know how to get rid of Americans, by killing them so that public opinion will put an end to things.”7

Aideed, of course, was proven to be correct. And the withdrawal from Mogadishu not only was a humiliating defeat for the United States but it also reinforced perceptions of America’s lack of resolve and further complicated U.S. efforts to achieve its goals through threats of force alone.

This initial judgment, this basic “default setting” conditioning foreign leaders to believe that U.S. military power can be withstood, has made it extremely difficult for the United States to achieve its objectives without actually conducting military operations, despite its overwhelming military superiority. With the targets of U.S. diplomacy predisposed to disbelieve American threats, and to believe they can ride out any American military initiative and drive away American forces, it has been necessary for the United States in many incidents to go to great lengths to change these individuals’ minds. Reaching this defining moment, the point at which a foreign decision maker comes to the realization that, despite what may have happened in the past, in the current situation U.S. leaders are committed and, if necessary, will persevere in carrying out violent military actions, has become a difficult challenge in U.S. diplomacy. It also creates a large obstacle to resolving conflicts and protecting U.S. interests while avoiding military confrontation.

HOW THREATS ARE EVALUATED

There is a rich literature on the use of force in world affairs and a considerable body of writing on the particular problems of the use of American military power in the post-Cold War period. Some voices in this debate include Gacek (1995), George (1995; George and Simons, 1994), Jentleson (1997), Damrosch (1993), the Aspen Strategy Group (1995), and

Muravchik (1996). There is also a large body of memoirs and contemporary histories testifying to the perceptions of American decision makers in particular incidents. Some examples are Baker (1995), Powell with Persico (1995), Quayle (1994), Schwarzkopf with Petre (1992), Woodward (1991), and Bush and Scowcroft (1998).

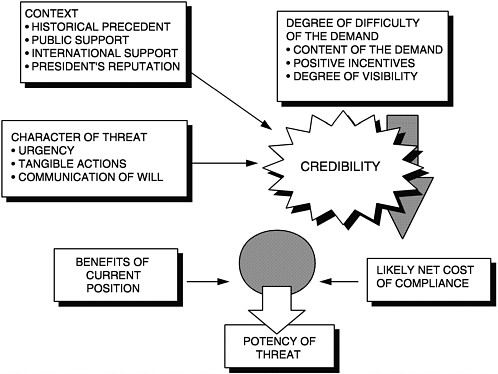

The authors of this literature have made any number of observations as to the conditions that facilitate the effective use of military threats. Typically, these conditions are not proposed as prerequisites for effective threats but merely as elements that make it more likely that threats will succeed. We therefore term these variables enabling conditions. The large number suggested in the literature, many of which differ from one another only in nuance, can be grouped into two broad categories. Most enabling conditions shape the credibility of the U.S. threat in the minds of the targeted foreign leaders; these include both conditions pertaining to the context in which the U.S. threat is made and to the character of the threat itself. Quite apart from the credibility of the U.S. threat, however, some demands are more difficult for foreign leaders to comply with than others, and some of the enabling conditions directly affect this perception of how costly it would be to comply with the demands. Together, the credibility of the threat and the degree of difficulty of the demands shape the targeted leader’s evaluation of the likely cost of complying, or of not complying, with U.S. demands. The balance between the cost of compliance and the cost of defiance represents the potency of the U.S. threat.8 These relationships are expressed in Figure 3.1 and are discussed further below.

Enabling Conditions

The context in which a threat is made and the character of the threat itself together shape the credibility of the threat. The degree of difficulty of a demand is evaluated through this credibility screen to determine the likely costs of compliance and noncompliance.

Context of the Threat

In previous work on this subject, Stephen Kaplan and Barry Blechman determined that coercive uses of military power by the United States were most likely to be successful when the United States acted in an appropriate historical context, when there was precedent for its demands and actions. This stands to reason. We know from experience that reaffirmations of long-standing positions are more likely to be taken seriously than declarations of new demands, particularly when the credibility of the traditional claim has already been tested through force of arms and found to be genuine. Targets of new claims of U.S. vital interests may

FIGURE 3.1 Evaluation of threats.

quite naturally want to test the claimant’s seriousness. Such a challenge, when it occurs, means that the threat is ineffective, and the goals of the U.S. demands must be asserted through direct military action. Precedents may also have negative effects; as we shall see, the fact that U.S. military power was resisted successfully in Vietnam and elsewhere by weaker military powers seems to have adversely affected the credibility of U.S. military threats in recent years (Blechman and Kaplan, 1978; Jervis et al., 1985; Schelling, 1966).9

A second contextual factor believed to shape the credibility of U.S. military threats is the presence or absence of broad public support for military action and, particularly, whether or not there is wide support among members of Congress. Obviously, as in the case of Vietnam, domestic dissent raises the possibility either that the United States will not act on its threats if challenged or that, even if it does act, the force of public opinion will sooner or later, probably sooner, compel a retreat. This does not necessarily mean that any dissent negates a president’s threats; the effect of dissent presumably depends on the importance attributed to it by the intended target. Nonetheless, because since Vietnam there has only rarely been broad public support for U.S. initiatives involving the

threat or use of military force—at least prior to the actual and successful conduct of the operation—there is usually evidence that foreign leaders can cite in persuading themselves and their people that the Americans can be made to back down.10

The presence or absence of third-nation support for the U.S. position is a third contextual factor that seems to influence perceptions of the credibility of a U.S. threat. Allies’ protests can curtail the willingness of the United States to act on its threats or to persevere in any military action needed to respond to a challenge, for fear of incurring high costs in more important relationships. This factor has become increasingly important in assessments of threats or uses of force in recent years, as the United States has become increasingly reluctant to act without allies in the new types of situations that have emerged following the Cold War. As with all the enabling conditions, what matters is not the reality of allied support but the targeted leader’s perception of this factor. In explaining Saddam Hussein’s disbelief of American threats during the Persian Gulf conflict, for example, former Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney cited Hussein’s belief that the United States could never carry out military operations in Iraq itself because—in Hussein’s view—the Arab nations allied with the United States would make clear that in such circumstances they would have to leave the coalition.11

A final contextual factor often said to influence the credibility of U.S. threats is the reputation of the president and other high-level U.S. officials. The scholarly literature is mixed in its assessments of the importance of this factor, however, and the case studies examined for this project shed no light on the subject—no discernible difference could be seen in responses to threats by Presidents Bush or Clinton that would seem to pertain to the incumbent’s reputation. More basic attributes of U.S. credibility and of the situation itself seem to have been more important.

Character of the Threat

Other factors contributing importantly to the credibility of threats reflect the manner in which they are conveyed. A sense of urgency must be part of the threat or the targeted leader can believe that a strategy of delay and inaction will be effective in avoiding compliance. The establishment of deadlines appears to be particularly important (George and Simons, 1994). In 1989 Panamanian strongman Manuel Noriega understood well that the United States would prefer to see him removed from power and democracy restored. But because the United States endorsed negotiations by the Organization of American States (OAS) with Noriega and never articulated an “either-or” threat of Noriega’s forcible removal, he apparently interpreted U.S. rhetoric as bluster and dismissed stepped-

up American military exercises in the Panama Canal Zone as “mere posturing” (Grant, 1991; Kempe, 1990; Treaster, 1989).

Verbal threats are also more effective when accompanied by tangible military actions—steps that indicate the seriousness of the U.S. undertaking. Not only can movements or other actions by military units demonstrate actual capabilities, thus lending verisimilitude to threats, but by demonstrating the U.S. president’s willingness to pay a price for the situation, they add credibility to his verbal demands. In this respect the greater the commitment demonstrated by the action, the more likely the threat is to be successful. Thus, Blechman and Kaplan (1978) found the deployment of forces on the ground in the potential theater of operations to be a more effective means of making threats credible than the movement of naval forces, as ground deployments demonstrate a willingness to pay the political price by putting U.S. soldiers, or air men and women, at risk. Similarly, the mobilization of military reserves has been an effective means of adding credibility to threats. Disrupting the lives of U.S. citizens by placing them on active duty, separating them from their families and workplaces, indicates indisputably the president’s willingness to pay a high political price to get his way.

Difficulty of the Demand

The context and character of a threat determine its credibility in the mind of the target. But whether a foreign leader chooses to comply with a U.S. demand is also conditioned by the degree of difficulty of the demand itself. To be effective, a demand must obviously be specific, clearly articulated, and put in terms that the target understands. There is no shortage of cases in which the targets of military threats simply did not understand what was being asked of them and therefore could not have acted to satisfy U.S. demands even if they had wanted to.12

In addition, a demand can be more or less onerous for the targeted leader to contemplate. In part this evaluation will depend on the demand’s specific content: What is, in fact, being demanded? At the extreme, some demands may not be satisfiable by the target. In some cases the United States (and other nations) have misread situations, demanding actions that the target of a threat was not capable of delivering. This may have been the case in U.S. relations with the Soviet Union over the Middle East in the 1960s and 1970s, for example, where the United States threatened repeatedly but seems to have misjudged the Soviet Union’s ability to influence certain Arab nations and factions (Whetten, 1974).

The inclusion of positive incentives in the overall U.S. diplomatic strategy is an important way of improving the targeted leader’s perception of a U.S. demand. Not only do positive incentives change perceptions of the

content of a demand itself, they also provide a political excuse for the target to do what it might have wanted to do anyway: back down and accept the U.S. demand.

A targeted leader’s perception of the difficulty of a demand also will be affected by the degree of visibility of the retreat required. Regardless of substance, an act of compliance that can be taken invisibly is far easier to accept, as it may not convey additional political costs. A retreat that is visible and humiliating may often be perceived as something to be resisted at any cost.13

It has been demonstrated in many studies that threats or limited uses of force are more likely to be effective when the behavior demanded of a target requires only that the target not carry out some threatened or promised action. This is a subset of the visibility factor: deterrent threats are more likely to succeed than compellent threats; the latter require the target to carry out a positive and therefore usually visible action. In the case of deterrent threats, on the other hand, it is usually unknown, and unknowable, whether or not in the absence of U.S. threats the target would have carried out the action being deterred. Would the Soviet Union have attempted to seize West Berlin in the late 1950s or early 1960s if the United States had not threatened to contest such an initiative with military force? No one can say with certainty. Thus, deterrent threats may appear to be more successful because they are sometimes used to deter actions that would not be carried out in any event. Moreover, in those deterrent cases in which the initial threatened action would otherwise have been carried out, it is easier politically for the target to back down, as it need not be done in public; the target can always claim that, regardless of the U.S. threat, it would not have acted in any event. When the U.S. threat requires a positive act on the part of the target (e.g., withdrawal from Kuwait), the retreat is publicly evident and could have dire consequences in national or regional politics.

Potency of the Threat

All of these enabling conditions—context of the threat, character of the threat, and degree of difficulty of a demand—contribute to a targeted leader’s understanding of the cost of complying, or of not complying, with U.S. demands. In Alexander George’s phrase, an effective threat must be potent relative to the demand. This means that the target must perceive that the threat, if carried out, would result in a situation in which the target would be worse off than if it complied with the U.S. demand. If, for example, the demand is that a ruler give up the throne, the only potent threat is likely to be that otherwise the ruler will be killed (or that a situation would be created in which the ruler might be killed). Any threat

less potent would likely be seen—even if it were carried out—as resulting in a situation no worse, and possibly better, than that which would have resulted from satisfying the demand. This evaluation, of course, will be filtered through the target’s perception of the credibility of the threat— how likely it is that the anticipated punishment will be carried out. If the threat is perceived to be wholly incredible, the anticipated cost of noncompliance will be low. If the context and character of the threat add verisimilitude, however, the difficulty of the demand will be weighed carefully relative to the cost of noncompliance, and a sufficiently potent threat should produce compliance in a rational opponent.

CASE STUDIES

All these enabling conditions were examined for each of the eight major cases in which military force was threatened or used in limited ways in support of diplomacy during the Bush and first Clinton administrations. Although the authors examined each case extensively, only a brief summary of each can be presented in this paper; the summaries highlight the key findings.

Panama (1989–1990)14

The Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega was an agent of U.S. policy in Central America for many years. In the late 1980s, however, his value declined with settlement of the Nicaraguan insurgency, and he became increasingly and more openly involved with the Colombian drug cartels. After he was indicted in the United States in February 1988 for drug trafficking and money laundering, first the Reagan administration and then the Bush administration decided to seek his removal from office. As tensions grew between the two countries in 1988 and 1989, the Panamanian Defense Forces, one key source of Noriega’s power, began to harass U.S. military personnel in the country and in the Canal Zone, as well as to step up repression of the democratic opposition in Panama.

Because of the upcoming presidential election, the U.S. government did not initiate serious pressures against Noriega until 1989. Beginning in April of that year, however, the United States tried to make clear that it considered Noriega an illegitimate ruler and that it wanted him to step down. It renewed economic sanctions against Panama, gave Panamanian opposition parties $10 million in covert assistance toward their effort in the scheduled May presidential elections, and provided election observers. After Noriega manipulated the elections, the United States initiated a variety of diplomatic actions, including recalling its ambassador. The Bush administration worked through the OAS to negotiate Noriega’s res-

ignation and also carried out a series of military exercises and other actions in the Canal Zone intended to make the U.S. military presence there more visible. Noriega continued to refuse to comply with U.S. demands, however, and survived a coup in which the United States played a minor role. When a U.S. naval officer was murdered in December 1989, President Bush quickly authorized the U.S. armed forces to invade Panama, capture Noriega, and bring him to the United States for trial.

In this case, therefore, both diplomacy and military threats failed, necessitating the direct use of military force in war to accomplish the U.S. objective. Why was this the case? The main reasons appear to be related to the context and character of the threat itself. Despite any number of statements by U.S. leaders indicating that they believed Noriega should step down and that they considered him an illegitimate ruler, it was never stated clearly and definitively that the United States would be willing to invade the country and throw Noriega out if he did not comply with the demand to relinquish office.15 In short, no cost was ever specified for noncompliance with U.S. demands; hence, a potent threat was never made. The United States demanded that Noriega leave office and, although a threat to expel him by force might have been inferred from U.S. statements, it was never stated explicitly. Nor was any deadline set for his compliance with the demand to relinquish office; Noriega was permitted to defer action for months without any obvious penalty. Likewise, U.S. verbal demands were not directly supported by tangible military actions. Although reinforcements were sent to the Canal Zone and some exercises were held there, they were all downplayed by U.S. officials and explained by a general concern for the security of the Canal Zone in light of deteriorating U.S.-Panamanian relations (Buckley, 1991). Colin Powell has stated that the limited military actions taken by the United States in 1988 and 1989 probably reinforced Noriega’s preexisting perception that the United States was irresolute and that he could persevere.16 When the invasion force was assembled, it was done in secrecy and never displayed publicly or brandished in support of an ultimatum that Noriega surrender or face forceful expulsion. This approach, of course, was dictated by the Weinberger maxims of how to use military power effectively.

It was harder for U.S. officials to threaten effectively in this case because the demand was extremely difficult for the target to contemplate. Noriega was being told to relinquish office; this was not a deterrent, but rather a compellent, situation. Only a clear and potent threat might have had a chance of success and, as noted earlier, in this case the target really did not understand that he faced a serious threat of U.S. action.

In the Panama case, in short, there was no defining moment because of the U.S. failure to make clear its compellent threat. The United States

did not explicitly state the action it was prepared to take if its demand was not satisfied. Nor did it demonstrate a credible willingness to enforce the demand. No deadline for action by Noriega was established. The U.S. target, Noriega, never had to contemplate the seriousness of the U.S. resolve until it was too late for him to yield. U.S. leaders failed to press him into a defining moment.

U.S. Relations with Iraq (1990–1996)17

Eight months after the successful military operation in Panama, the Bush administration faced a far greater challenge in the Persian Gulf. In this case the threat of force was a central element of the U.S. strategy from nearly the outset of the crisis. President Bush and all other senior officials stated repeatedly and unequivocally that, if Saddam Hussein did not withdraw Iraqi forces from Kuwait, the United States was prepared, with the help of its allies, to expel them by force of arms. The threat was made increasingly credible throughout the remainder of 1990 by the mobilization and deployment of an enormous U.S. and allied military force in the region, an operation that could have left no question in Hussein’s mind about the president’s willingness to run huge political risks to implement the threat. Furthermore, the president’s credibility was strengthened by the forging of a broad coalition that backed the American action, including Arab nations as well as traditional U.S. allies, by authorization of the allied military action by the UN and of U.S. military action by Congress, and by the establishment of a clear deadline for compliance that imparted a definite sense of urgency. Finally, the United States initiated an air campaign prior to launching its ground offensive, providing even more evidence of its military prowess and will and offering a final opportunity for Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait rather than being thrown out.

The context and character of the U.S. threat would have predicted success. Yet all these measures failed; in the end, U.S. and allied armies had to invade Kuwait and compel the Iraqi retreat by force of arms. Why? Because of the opacity of the Iraqi regime, the answer may never be clear, although several possibilities come to mind.

Despite their visible display in the theater of operations, Hussein may still have underestimated U.S. military capabilities relative to Iraq’s. He may have believed that the war would be far less one sided, causing sufficient U.S. casualties for President Bush to end (or to be forced by U.S. and allied opinion to end) the hostilities short of the full expulsion of Iraqi forces from Kuwait. If so, he would have been counting heavily on the considerable opposition in the United States to the use of force prior to the authorizing legislation, as well as the obvious fragility of the coalition that

had been brought together for the war (Bengio, 1992). He also simply may not have understood the extent of U.S. and allied power. Then Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney believes, for example, that Hussein’s subordinates were afraid to bring him bad news or negative evaluations, as he was known to treat such messengers as traitors.18

Alternatively, the U.S. threat might simply not have been potent enough relative to the demand being made. The United States never threatened to unseat Hussein or to destroy his regime if Iraqi occupation forces were not withdrawn from Kuwait.19 The threat was deliberately restricted to the destruction or expulsion of Iraqi forces in Kuwait, in part because Arab coalition members would not or could not support a more ambitious threat to destroy the Iraqi regime. From Hussein’s perspective, in the context of his strategic vision, a military defeat while retaining power might have seemed preferable to an ignoble retreat. He might first have miscalculated and believed that the United States would not act to expel him from Kuwait but, subsequently, when he realized the error, figured that in terms of his overall goals in the region, and in terms of the likelihood of his being able to hold on to power in Baghdad, it would be better to be defeated militarily by the overwhelming forces that had been arrayed against him than to knuckle down to U.S. demands (Stein, 1992). If this was the case, only a credible threat to destroy Hussein and his regime would have been potent enough to have achieved the objective—liberating Kuwait—without the direct use of military forces in war. In the absence of such a potent threat, Hussein never had to face a defining moment.

Because of this ambiguous outcome—military triumph for the United States but political survival for Saddam Hussein—threats and uses of force have remained a central element in U.S. relations with Iraq since the Gulf War ended. Immediately following the war, the United States and its allies, acting through the UN, intervened on the ground to protect the Kurds in Iraq’s north and established no-fly zones in both the north and the south to protect the Kurds and the Shi’a minority, respectively, from Iraq’s air force. Both actions were accompanied by covert support for rebellious elements in the two regions intended to destabilize the Hussein regime. The no-fly zones have been enforced through combat air patrols and, occasionally, by air and missile strikes against radars, surface-to-air missiles, and command facilities.

The last such incident during the first Clinton administration took place in September 1996, when the United States once again struck at air defense sites in the south of Iraq, this time in response to an Iraqi intervention in a conflict between two Kurdish factions in the north. The United States maintained that the Iraqi military action was unacceptable and responded both by reinforcing its forces in the Gulf region and by launching cruise missile attacks on newly rebuilt Iraqi air defense sites in

the south. (The United States took no action directly in the Kurdish region.) When Hussein seemed to defy U.S. injunctions regarding the need for Iraq to respect the no-fly zone in the south, the United States threatened more devastating air strikes against Iraq (and moved aircraft into the region that would be capable of carrying them out), and Hussein seemed to comply with the U.S. demand.

In an odd incident earlier in the Clinton administration, the United States launched cruise missile attacks against Iraq in retaliation for a plot by Iraqi intelligence agents to assassinate former President Bush during a visit to Kuwait. The plot was uncovered before the assassination attempt could be made, but the United States retaliated anyway to punish Iraq and deter future incidents. The cruise missile attacks, which included a strike on an Iraqi military intelligence headquarters said to be implicated in the plot, were intended to indicate to Hussein that such acts of terror and similar covert operations would not be tolerated.

An even more dramatic threat of American military force in the Persian Gulf took place in August 1994 when, in response to the movement of Iraqi armored forces toward Kuwait, the United States deployed substantial quantities of naval and land-based air and ground forces to the Persian Gulf and stated that it would resist any new invasion with force. The United States had been building up its capabilities and facilities in the Gulf ever since the 1991 war and used the occasion of the Iraqi armored movements to reinforce its presence there so as to deter any new invasion of Kuwait. The Iraqi units withdrew soon after the U.S. reinforcements arrived, and the Clinton administration claimed that its threats had succeeded. This claim is uncertain, however, as many observers maintained that the Iraqi leader could not possibly have contemplated an invasion given the experience in 1991, the much weaker state of the Iraqi armed forces, and the much greater preparedness of the United States and its allies three years later.

This sequence of incidents presents interesting evidence about the difficulty of utilizing military threats. In each episode the United States was apparently successful: the no-fly zones have generally been respected; there have been no publicly known Iraqi terrorist plots directed against American targets since U.S. retaliation for the planned assassination of President Bush; and there have been no further overt threats against Kuwait since 1994. Yet in the larger strategic sense the United States has failed. U.S. interests would be served most effectively either by the fall of the Hussein regime or by a radical change in Hussein’s behavior such that he complies willingly with U.S. wishes. But the Hussein regime continues to skirt UN resolutions and the terms of the agreement that ended the war, continues to terrorize its minority populations, continues to behave belligerently toward Kuwait and other states in the re-

gion and, periodically, continues to challenge the United States politically. In short, the United States has had to settle for a lesser objective: containment. In the words of one U.S. official, U.S. diplomacy and military activity have served at best “to put Hussein back in the box.”

This failure has occurred despite the fact that most of the enabling conditions surrounding U.S. policy are positive. There is now precedent for the actions, the U.S. public is very supportive, and the allies have generally cooperated (when they have not, the United States has been willing to act unilaterally). All the enabling conditions that determine the context and character of the threats are positive. While the demands made have varied in their degree of difficulty, none have been onerous. The failure, then, appears to be the result of the potency of the threat relative to the demand. As in the Gulf War, the United States and its allies have not been willing to make and, if necessary, carry out the one threat that might accomplish their long-term strategic interest. It is evident that the United States is not willing to topple the Hussein regime through force of arms or even to enforce its more far-reaching demands.

The weakness of the U.S. and allied position became evident in the 1996 incident. In response to Iraq’s military action against a Kurdish faction in the north, which U.S. leaders termed unacceptable, the United States was only willing to stage symbolic attacks against Iraqi air defense facilities in the south—far from the scene of the Kurdish conflict. This time most of the allies were unwilling to go along with the action, and open dissent weakened the coalition. The crisis worsened for a time as Hussein seemed to defy U.S. demands about the southern no-fly zone. While he ultimately gave in, the broader U.S. strategic objective of containment was threatened. Hussein reasserted control over significant territory in the north and dismantled the Kurdish opposition. Once again, U.S. demands were not sufficiently potent to bring Hussein to a defining moment.20

Somalia (1992–1995)21

The disastrous U.S. intervention in Somalia probably did more to undermine worldwide perceptions of the efficacy of U.S. military power than any event in recent memory. Among other things, American actions in Somalia influenced the calculations of leaders in Haiti and Bosnia as they confronted U.S. threats simultaneously.

In Somalia, largely as a result of inattention at political levels, the United States allowed its military forces to transform their original humanitarian mission into a coercive activity intended to enforce a peaceful settlement of the underlying political conflict by disarming factions in a particular section of the country. When one faction resisted and killed 24

members of the Pakistani component of the UN peacekeeping force, the United States launched a low-level military offensive directed specifically against that faction. When U.S. forces suffered a tactical defeat in October 1993, Washington suddenly curtailed its objectives and announced that it would withdraw virtually all U.S. forces from the country.22

Once U.S. forces assumed the larger political role, the mission became extremely difficult. Most of the enabling conditions with respect to the context of the threat were negative. There was no significant precedent for U.S. involvement in Somali politics, and the American public did not support the mission beyond its initial humanitarian boundaries. Other countries with troops participating in the UN mission were extremely reluctant to undertake any actions implying a threat of conflict. The degree of difficulty of the demand escalated sharply once the U.S. offensive against Mohamed Farah Aideed began. Finally, because of the shift in objectives, the U.S. demands were unclear—to U.S. officials and the U.S. public as well as to the Somali targets. Also, the Somali leaders were constrained by their mutual competition, as well as by internal conflicts within their respective factions, making it unclear whether compliance with U.S. demands was ever feasible.

Nonetheless, the character of the threat suggested potency. A clear sense of urgency was implied, and positive inducements for compliance were supplied—yet the threat and use of force both failed. The clearest reason was noted previously and stated by the faction leader, Aideed, to the U.S. negotiator. Based on his understanding of recent U.S. history, he believed that the United States could not sustain a campaign against him in the face of casualties. The lack of precedent for the U.S. action in Somalia and the dissension already evident in the United States and among its allies served to confirm his preexisting view that the United States could not sustain its threats against even nominal opposition. The U.S. threat was not credible because contextual factors reinforced the target’s preexisting judgment about U.S. credibility.

Macedonia (1992–1996)23

The deployment of U.S. and other nations’ ground forces to Macedonia to deter any extension of the Bosnian war to that nation, or any internal ethnic conflagration, represents an apparent success for U.S. military threats. Despite their reluctance to become involved in Bosnia itself, first the Europeans and then the United States were willing to deploy troops to Macedonia as a means of guaranteeing their involvement should the conflict spread. As noted, the deployment also was intended to strengthen warnings to Serb leaders not to tighten oppression of the Albanian population in Kosovo, a secondary aim that was ultimately not

achieved, as evidenced by the 1999 Serbian offensive in Kosovo. In a way the unwillingness of U.S. leaders to take decisive action in Bosnia at the time made Macedonia seem more important in the eyes of Washington decision makers. It was a means of demonstrating some “on-the-ground” involvement and a willingness to prevent a widening conflict, thereby, it was hoped, earning some credits with the Europeans.

In this case, virtually all the enabling conditions were positive. There was support in the Congress, unanimity among the allies, the demand was stated clearly and reinforced by military actions, and the threat (automatic involvement in any extension of the Bosnian conflict) was potent relative to the demand. Its self-implementing nature intrinsically conveyed a sense of commitment and urgency.24

Of course, the U.S. threat with respect to Macedonia had another great advantage. It was intended to deter hostile actions whose likelihood was not clear. Whether or not the Serbs or anyone else might have tried to extend the Bosnian conflict to Macedonia absent the allied deployment of ground forces there is anyone’s guess. The threat might have worked because the degree of difficulty of the demand was low. Compliance with the demand required no visible action; in fact, it might have required no action at all.

Bosnia (1992–1996)

The Bosnian war and its accompanying humanitarian tragedies bedeviled both the Bush and the Clinton administrations. Throughout the conflict, threats and limited applications of force have been used for tactical purposes, with mixed results. Early in the conflict, the United States and its allies established a no-fly zone to protect their humanitarian shipments and forces, and the threat of selective air strikes was employed to remind the Serbs of these rules—generally with some tactical success. On the other hand, the United States and its allies, working through the UN, threatened and used limited amounts of force repeatedly in efforts to protect the so-called safe areas from Serb encroachments and subsequent mass murders. These efforts failed miserably, climaxing with the occupation of Zepa and Srebrenica in 1995 and the murder of thousands of their residents.

On the strategic level, from the earliest days of the Clinton administration, U.S. leaders repeatedly threatened a deeper level of involvement in the conflict if Serb forces did not comply with various resolutions. The United States also deployed a considerable number of forces to the Adriatic and to Italian air bases, helping to enforce sanctions against Serbia and an arms embargo in Bosnia, as well as carrying out the limited strikes mentioned above. But the vagueness of the U.S.

strategic threats encouraged Serb intransigence and continued Serb efforts to seize additional territory. The appearance of a lack of American resolve was compounded by clear indications that the United States was not willing to deploy ground forces to Bosnia and that the allies were willing to deploy troops but not to place them in danger, as would be required by any serious effort to compel Serb compliance with Western demands. It was not until August 1995, following the atrocities in Zepa and Srebrenica and the successful Croat offensive against the Serbs, that the United States and its allies made a serious effort to pressure the Serbs into entering peace negotiations by carrying out repeated air strikes against a variety of targets. Soon thereafter the Dayton talks were begun and the peace agreement now being implemented was concluded. Whether the Serbs were brought to the peace table by the Croat offensive, the new allied will to end the conflict suggested by the air campaign, or their own weariness with war and sanctions is anyone’s guess. Whether the peace will last is an even greater unknown. In the post-Dayton phase, of course, the United States and its allies again used military force, deploying ground troops of the Implementation Force, or IFOR, throughout Bosnia to help keep the peace. IFOR was successful in ensuring that the parties observed the military aspects of the Dayton Accords and completed its mission in December 1996. (It has been succeeded, of course, by a smaller force known as the Stabilization Force, or SFOR.)

In the end, therefore, U.S. strategic threats appear to have been successful in persuading the Serbs to stop fighting and start talking, or at least were coincident with success. But this one success capped a long period of clear failure, consistent with the negative values of most of the enabling conditions in this case. All the contextual variables were negative: there was no precedent for U.S. involvement in the former Yugoslavia, the Congress and the American people were starkly divided as to the wisdom of U.S. involvement, and the allies were obviously reluctant to risk the lives of their soldiers. The credibility of the threat was strengthened by the deployment of forces, but the actual uses of these forces were so limited as to convey a message of reluctance and weakness rather than of strength. This is certainly the view of Undersecretary of Defense Walter Slocombe, who has said that “UNPROFOR’s mistake was tolerating hostile behavior. It should have slapped down the people who were shooting at them.”25

Similarly, the enabling conditions pertaining to the final demand made of the Serbs were mainly negative. The U.S. demand to halt the war was not articulated clearly until the final air offensive, and no sense of urgency was conveyed until then. The U.S. objective was to compel participation in a peace process, rather that deter certain actions, requiring a

positive and visible step by the target. And that target—Serbia’s president—often was unable to deliver the Serb leaders in Bosnia even when he wanted to meet the U.S. demands.

The enabling conditions only turned positive, for the most part, following the massacres at Zepa and Srebrenica and the beginning of the massive NATO air strikes. As the air strikes continued, they not only raised the cost of noncompliance but also encouraged the development of a sense of urgency among Serb leaders. At this point, the choice became more clear to the Serbs—peace or destruction of the military infrastructure of the Bosnian Serbs. Given other conditions at the time, particularly the successful Croatian ground offensive that was changing the entire strategic situation and the evident weariness with the war in Serbia, the U.S. threats at last gained the potency necessary to achieve their objective. Then Secretary of Defense William Perry, in fact, believes that he can identify the defining moment: a visit by the chiefs of the U.S., British, and French armed forces to Bosnian Serb military leaders in Belgrade, on July 23, 1995, to convey the new resoluteness of the NATO nations in the aftermath of the Srebrenica massacres.26

The picture that thus emerges with respect to the efficacy of U.S. military threats in Bosnia is mixed. For the most part the threats failed, mainly because the element central to their potency—a willingness to deploy U.S. ground troops and to utilize European forces already on the ground—was missing. Seeing the disarray in the United States and the dissension among the allies, the Serbs had little reason to comply. Only when the NATO allies, reacting to the murders in Srebrenica and the Croat offensive, made clear that they would be willing to act more forcefully did the Serbs perceive a real cost to their noncompliance and begin to take the allies’ threats seriously.

Haiti (1994–1996)27

Haiti presents a similar picture: ineffective threats and excessively limited military actions showed U.S. irresoluteness for a considerable period of time but were followed by a potent threat that finally achieved its objective.

The crisis in Haiti actually began in 1991, when a military coup expelled the country’s first elected president, Jean Bertrand Aristide. The United States pursued a diplomatic strategy to reinstall the president, accompanied by sanctions, for more than two years. Only when the Governor’s Island agreement that would have permitted Aristide to regain office failed in the fall of 1993, and the Haitian military government turned back a U.S. ship delivering the lead element of a UN peace-

keeping force, did the United States threaten to overthrow the military government and reinstall Aristide by force, if necessary.

The turning away of the U.S. ship followed closely on the defeat of U.S. forces in Somalia, a coincidence that was particularly harmful to the efficacy of U.S. threats (Ribadeneira, 1994; Downie, 1993a, 1993b). For the next eight months the United States made numerous demonstrations of its military capabilities through deployments of Navy and Marine forces off the island and by staging exercises intended to show practice for an invasion. Yet the Haitian ruler, General Raoul Cedras, with virtually no means of defending himself if the United States did invade, refused to back down. Finally, President Clinton received authorizations to utilize military force from the OAS and the UN and set a deadline for the invasion. Still, the Haitian ruler refused to back down. It was only when he received word that U.S. airborne troops had left their bases and that the operation was actually under way that he accepted a U.S. offer, conveyed by a delegation chaired by former President Jimmy Carter, to step down with some semblance of dignity and a guarantee of safety.

It should have been easier to make effective threats in the Haitian case than in Bosnia. While U.S. opinion tended to oppose the use of American forces in both cases, there was ample precedent for U.S. interventions in Haiti and the Caribbean and most other hemispheric nations were supportive. The demand was clear, the target could easily comply, the threat was potent relative to the demand, and U.S. military power was displayed with great visibility. There were also positive inducements for compliance: U.S. representatives offered to provide for the personal safety of the Haitian dictator and his family.

Why, then, was it so difficult to make a threat that worked? Why was it necessary to actually launch a huge invasion force before Cedras would believe that President Clinton was truly committed to his ouster? Two factors relating to the context of the U.S. threat seem to have been essential. First, the opposition of much of the American public and Congress to invasion plans may have conveyed hope to Cedras that Clinton could not possibly go through with his threats. Indeed, knowing that he would be defeated, Clinton did not seek congressional authorization for the invasion. Second, particularly in view of this opposition, Cedras may have taken heart from the recent American behavior in Somalia, as well as from his success in compelling the ship carrying UN peacekeepers to withdraw.28 He may have believed that, even if the United States did invade, all his forces would have to do would be to inflict some casualties and the Americans would withdraw. If this is the case, the persuasiveness of the Carter mission, which made clear both the magnitude and commitment

of the U.S. effort and provided positive inducements for compliance, was essential in increasing the potency of the U.S. threat and bringing Cedras to his defining moment.

Korea (1994–1996)29

The Korean case is probably the most successful use of military threats during this period. Essentially, in this case, threats of military force were used as one element in a strategy that concentrated mainly on using economic instruments—both positive and negative—to halt the North Korean nuclear weapons program. While threats were not the most prominent element of the strategy, they clearly played a role, enforcing boundaries on Pyongyang’s choices. According to Walter Slocombe, when Pyongyang tried to counter the U.S. threat to impose economic sanctions by stating that such an action would constitute an act of war, the United States made clear that it was willing to escalate along with North Korea through visible efforts to increase its readiness for war on the peninsula.30

The threats generally were vague in character and articulated indirectly. Neither the president nor other high-ranking U.S. officials threatened explicitly to destroy North Korea’s nuclear facilities, but the administration let it be known that it was considering military options and reinforced the message by strengthening its presence in South Korea with air defense missiles and other items. Consultations with the U.S. commander in Korea to discuss possible military options were held with a fair amount of publicity. The fact that prominent Republicans, such as former National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft, were calling for military strikes reinforced the message that the administration could not rule out direct military action if negotiations failed.

Enabling conditions in this case were generally positive for effective threats. The U.S. interest and willingness to use force in Korea had strong precedent, public opinion and the Congress supported the need to do something about North Korea’s nuclear weapons program, the demand was clear, and the threat was supported by visible military actions. The major negative condition was that the U.S. ally, South Korea, was reluctant to see the crisis get out of control, as it faced the possibility of major casualties if combat resumed on the peninsula.

In the end, North Korea probably ended its nuclear program because it had gotten what it wanted—an economic payoff and, more importantly, the beginning of a dialogue with the United States that might lead eventually to normal relations. Still, U.S. officials believe that Pyongyang took the U.S. threats seriously and that they played some role in bringing about the so-far positive outcome.

Taiwan (1996)31

The final case is an odd one—more symbolic than real. In 1996 China staged a series of military exercises and missile tests near Taiwan as the latter moved toward an election in which opposition parties were campaigning on a platform that demanded independence from the mainland. The Chinese actions were apparently intended to intimidate the Taiwanese and to remind all other parties—particularly the United States—that China would not tolerate de facto Taiwanese independence indefinitely and especially would not tolerate overt steps toward a de jure sovereign status. In response, the United States sent an aircraft carrier task group through the straits that separate Taiwan from the mainland and later in the crisis deployed a second carrier near the island. The U.S. actions apparently were intended to remind China of the American interest in preventing Taiwan’s unification with the mainland by force.

Both parties’ actions, of course, were shadowboxing. China was probably not seriously contemplating invading Taiwan. It does not have the means to accomplish that goal, and Taiwan could probably defend itself against an invasion without U.S. help. Moreover, the fallout from such an action would set back China’s economic development immensely, as well as antagonize neighboring states (especially Japan) and trigger massive armament programs on their parts—a counterproductive outcome from China’s perspective.

But if China’s threat was not serious, neither was that of the United States. Despite a great deal of hype in the news media, both countries apparently understood that they were playing on a stage, making points for world opinion and for domestic audiences. Both Chinese and American statements explicitly discounted any risk of a U.S.-Chinese military confrontation and anticipated continued relations in the future (Burns, 1996). In this sense the U.S. threats were effective—the target, however, was not China but rather Taiwan and domestic U.S. audiences.

CONCLUSION

The results of the case studies discussed above are summarized in Table 3.1. The cases are arrayed in rows, moving chronologically from top to bottom. The outcomes of each case and a description of the enabling conditions constitute the columns.

Overall, the use of military power by the United States clearly failed in only one of the cases—Somalia. U.S. threats to use military force clearly succeeded in three—Macedonia, North Korea, and Taiwan. In the four other cases—Panama, Iraq, Bosnia, and Haiti—the use of military power ultimately succeeded, but either success came only with great difficulty,

at considerable cost to other U.S. interests, or the United States was successful only in achieving its immediate objectives, not its longer-term strategic goals. In Panama, Bosnia, and Haiti, success came only after long periods of failure, with high costs for the administration domestically and internationally; in Iraq each individual use of military power was successful, but the strategic situation remains unchanged and unsatisfactory from an American perspective; in Bosnia and Haiti the underlying political conflicts remain unresolved and easily reversible.

With respect to the enabling conditions, none alone appear to be a sufficient condition for success; nor can it be said for certain that any one condition—other than that the target indeed be able to fulfill the demand— is a prerequisite for success. Still, one noteworthy partial correlation can be seen between the difficulty of the demand and positive outcomes. In all seven successes (counting individual uses of force within cases as well as overall cases) but one, fulfillment of the U.S. objective demanded relatively little of the target. Typically, the actions required of the targets also tended to be less visible in these cases (with the exceptions of the action required of North Korea and of the Bosnian Serbs with respect to entering the Dayton negotiations). The U.S. posture in six of the seven successful uses of military power also included positive incentives, further reducing the difficulty of the demand as perceived by the target.

Enabling conditions pertaining to the credibility of U.S. threats (as determined by the context and character) present a less consistent pattern. There was precedent for U.S. action in only half of the cases, and the results were mixed in those cases with precedents and those without. Third-nation support and whether or not a sense of urgency was conveyed present no clear pattern. Tangible military actions were taken in all cases and hence shed no light.

The presence or absence of public support is more interesting. It was present in the three clear successes and absent in the one clear failure. The remaining four cases, which had mixed results, were also split with respect to public support. Public support for a threat evidently cannot guarantee its success, but an evident lack of public support apparently can make it difficult to make threats credibly. In Somalia and Haiti, as well as Bosnia for most of the conflict, the evident lack of public support in the United States for the policies being pursued by the administration—at least at the price level that potentially would be implied if the relevant threat had been carried out—seems to have given great comfort to the target of the U.S. action and encouraged him to attempt to stay the course. Evidence of public dissension was probably a factor encouraging Hussein to defy U.S. threats as well, and each of the former officials interviewed cited this factor as greatly complicating the use of military power by the United States.

TABLE 3.1 Outcomes and Enabling Conditions

|

|

Credibility |

Degree of Difficulty |

|||||||||

|

Case |

Precedent |

Public Support |

Third-Nation Support |

Urgency |

Tangible Military Actions |

Articulated |

Content |

Visibility |

Positive Incentive |

Potency |

Outcome |

|

I. Panama |

+ |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

− |

3 |

– |

– |

– |

YB |

|

II. Iraq (Strategic Outcome) |

− |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

2 |

− |

− |

− |

YB |

|

DS/DSa |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

2 |

– |

– |

– |

YB |

|

South no-fly |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

− |

2 |

– |

– |

+ |

YB |

|

Kurds |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

2 |

– |

+ |

– |

YB |

|

Terror |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

1 |

+ |

− |

+ |

S |

|

VWb |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

1 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

S |

|

III. Somalia |

− |

− |

− |

+ |

+ |

− |

2 |

− |

− |

− |

F |

|

IV. Macedonia |

− |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

1 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

S |

|

V. Bosnia (Strategic Outcome) |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

2 |

– |

+ |

+ |

YB |

|

Lift/no-fly |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

2 |

+ |

+ |

– |

YB |

|

Sanctions |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

2 |

+ |

– |

– |

YB |

|

Safe/weaponsc |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

2 |

+ |

– |

– |

F |

|

Dayton |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

2 |

– |

+ |

+ |

S |

|

IFOR |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

1 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

S |

|

VI. Haiti |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

3 |

– |

+ |

+ |

YB |

|

VII. North Korea |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

1 |

– |

+ |

+ |

S |

|

VIII. Taiwan |

+ |

+ |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

1 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

S |

|

aDesert Shield/Desert Storm. bValiant Warrior (1994). cSafe Havens/Weapons Exclusion Zones. Notes: The enabling conditions are generally labeled positive, meaning that they favored a successful outcome from the U.S. perspective, or negative, meaning the opposite. The one exception is the content of the demand made, which is ranked from 1 (least difficult for the target) to 3 (most difficult for the target). Outcomes are categorized as a success (S), failure (F), or “yes, but” (YB), meaning that the outcome eventually favored the United States but that getting there left a great deal to be desired. The Iraq and Bosnia cases are rated both for their strategic outcome and for specific uses of force within each case. |

|||||||||||

Looking beyond the scoreboard of results to the cases themselves, the question of potency also appears to be especially important. Potent threats relative to the cost of noncompliance were made in each of the clearly successful cases (Macedonia, North Korea, and Taiwan) and were not made in the one clear failure (Somalia). In the case of Iraq, as in Panama and in all but the so-far-final stage of the Bosnian conflict, the unwillingness of the United States to make threats that would clearly offer the target the prospect of an unacceptable cost seems to have been an important reason for the failure of U.S. policy.

The problem that the United States faces, therefore, is very clear. It is rare that it can both make potent threats and retain public support. Potent threats imply greater risks. And the American public’s aversion to risk, particularly the risk of suffering casualties, is well known; the legacy of Vietnam is real. This is particularly true in the types of conflict situations that have arisen since the end of the Cold War—where there is little precedent for American action, where American interests are more abstract than tangible, where the battle lines are uncertain, and where none of the contending parties wear a particularly friendly face.

Recognizing this public aversion to casualties, or predicting such opposition in particular cases, American presidents have been reluctant to step as close to the plate as has been required to achieve U.S. objectives in many post-Cold War conflicts. They have made threats only reluctantly and usually have not made as clear or potent a threat as was called for by the situation. They have understood the need to act in the situation but have been unwilling or perceived themselves as being unable to lead the American people into the potential sacrifice necessary to secure the proper goal. As a result, they have attempted to satisfice—taking some action but not the most effective possible action to challenge the foreign leader threatening U.S. interests. They have sought to curtail the extent and potential cost of the confrontation by avoiding the most serious type of threat and therefore the most costly type of war if the threat were challenged.

The American public’s sensitivity to the human and economic costs of military action is a clear legacy of the Vietnam experience. But it has been reinforced since then by sharp reactions—by the public and elected officials—to the suicide bombing of U.S. Marines in Beirut and to the deaths of U.S. soldiers in Mogadishu. Both Presidents Bush and Clinton have been keenly cognizant of this sensitivity, and their attempts to threaten to use military power have been hesitant as a result.

This syndrome would impair the effectiveness of U.S. coercive diplomacy under any circumstances, but its deleterious effects are magnified by the impact of those same historical events on foreign leaders. Vietnam syndrome is not solely an American disease—its symptoms are visible

abroad, when potential targets of U.S. threats see the American public’s sensitivity to casualties as a positive factor in their own reckoning of the risks and benefits of alternative courses of action. A review of the evidence reveals that Bosnian Serb leaders, Haitian paramilitary leaders, Saddam Hussein, and Somalia’s late warlord all banked on their ability to force a U.S. retreat by inflicting relatively small numbers of casualties on U.S. forces. That places American presidents attempting to accomplish goals through threats in a dilemma. Domestic opinion rarely supports forceful policies at the outset, but tentative policies only reinforce the prejudices of foreign leaders and induce them to stand firm.

Vietnam’s legacy abroad pushes foreign leaders’ defining moments back, requiring greater demonstrations of will, greater urgency, more tangible actions by U.S. forces, and greater potency for threats to succeed. But Vietnam’s legacy at home makes it much harder for U.S. presidents to take such forceful actions without significant investments of political capital.

As a result of this dilemma, American officials have often been unable to break through the preconceived notions of U.S. weakness held by foreign leaders to bring about a defining moment. Indeed, the cases in which decisive U.S. actions were taken only after long periods of indecision (especially Panama, Bosnia, and Haiti) may have only reinforced foreign leaders’ preconceptions about America’s lack of will. Until U.S. presidents show a greater ability to lead on this issue, or until the American people demonstrate a greater willingness to step up to the challenges of exercising military dominance on a global scale, foreign leaders in many situations will likely continue to see American threats more as signs of weakness than as potent expressions of America’s true military power. As a result, they will likely continue to be willing to withstand American threats—necessitating either recourse to force to achieve American goals or embarrassing retreats in the pursuit of American interests abroad.

This suggests that American presidents have several options when considering potential uses of military power in support of diplomacy:

-

They can pick their fights carefully, choosing to make public demands of other nations mainly in situations in which the actions they require will not be perceived by the target as excessively difficult, and when they can leaven their threats with positive incentives to encourage compliance, as in the cases of Taiwan and North Korea.

-

They can seek to “demilitarize” U.S. policy somewhat. Strategies close to those used in the Korean case may be more appropriate, and more effective, than the quick recourse to military threats seen in most of the other cases. Threats and limited military force have a clear role but more as reinforcing elements in policies dominated by economic,

-

diplomatic, and political factors than as the primary policy instrument. In Haiti it was ultimately a skilled diplomatic team backed by force, not the force itself, that secured Cedras’s removal from power. Given domestic constraints on U.S. ability to use military power, in threats or in actuality, Presidents Bush and Clinton may have leaned too heavily on the armed forces to advance American interests in the immediate post-Cold War world. Policies that deemphasize the role of force may be more appropriate more often.

-

When nonmilitary instruments of policy seem likely to be ineffectual but the U.S. president still perceives an imperative to act, and the foreign leader seems likely to perceive compliance with U.S. demands as onerous, the president must act decisively. In these situations the demand must be clear and urgent, the demonstration of military power incontrovertible, and the threat itself potent relative to the target’s alternatives. The ultimate achievement of U.S. objectives in Desert Storm and at the end of the Bosnian and Haitian scenarios demonstrates that presidential decisiveness can be effective, even at the later stages of a crisis. Most importantly, in Colin Powell’s words, “The president himself must begin the action prepared to see the course through to its end…. He can only persuade an opponent of his seriousness when, indeed, he is serious”32

NOTES

A version of this article appeared in Political Science Quarterly (1999) 114:1–30.

REFERENCES

Agence France Presse 1996a US postpones visit by Chinese defense minister. Agence France Presse, March 22.

1996b No firm date for Christopher-Qian meeting. Agence France Presse, March 22.

Aspen Strategy Group 1995 The United States and the Use of Force in the Post-Cold War Era. Queenstown, Md.: Aspen Institute.

BBC World Service 1991 Gulf Crisis Chronology. Essex, U.K.: Longman Current Affairs.

Baker, J.A. 1995 The Politics of Diplomacy. New York: Putnam.

Bengio, O., ed. 1992 Saddam Speaks on the Gulf Crisis: A Collection of Documents. Tel Aviv, Israel: Moshe Dayan Center.

Blechman, B.M., and S.S.Kaplan 1978 Force Without War. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

Blechman B., and J.M.Vaccaro, eds. 1995 Towards an Operational Strategy of Peace Enforcement: Lessons from Interventions and Peace Operations. Washington, D.C.: DFI International.

Buckley, K. 1991 Panama: The Whole Story. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Burns, R. 1996 Fallout from Taiwan tensions: U.S. cancels China talks. The Record, March 23.

Bush, G., and B.Scowcroft 1998 A World Transformed. New York: Alfred Knopf.

Damrosch, L.F., ed. 1993 Enforcing Restraint: Collective Intervention in Internal Conflicts. New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press.

Downie, A. 1993a U.S. diplomats in Haiti threatened, ship delayed. Reuters, October 11.

1993b Tense standoff in Haiti over U.S. troopship. Reuters North American Wire, October 12.

Freedman, L., and E.Karsh 1993 The Gulf Conflict, 1990–1991. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Gacek, C. 1995 The Logic of Force. New York: Columbia University Press.

George, A.L. 1995 The role of force in diplomacy: A continuing dilemma for U.S. foreign policy. In Force and Statecraft, 3rd ed., G.Craig and A.L.George, eds. New York: Oxford University Press.

George, A.L., and W.E.Simons, eds. 1994 The Limits of Coercive Diplomacy, 2nd ed. Boulder, Colo.: Westview.

George, A.L., and R.Smoke 1974 Deterrence in American Foreign Policy: Theory and Practice. New York: Columbia University Press.

Grant, R.L. 1991 Operation Just Cause and the U.S. Policy Process. RAND Note N-3265-AF. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corp.

Holl, J. 1995 We the people here don’t want no war. In The United States and the Use of Force in the Post-Cold War Era. Aspen Strategy Group. Queenstown, Md.: Aspen Institute.