CHAPTER 3

SIZING UP ADMINISTRATIVE PROBLEMS

Many of the problems of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) intramural program are described as administrative or bureaucratic and are related to NIH’s position as a research institution located within a large federal department, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). These particular problems can be organized around three major topics: (1) personnel, including compensation; (2) administrative barriers to a productive work environment; and (3) coping with a changing environment.

As stated in the introduction, the problems posed are neither new nor unique to NIH. Administrative problems seem to plague the entire federal government (National Academy of Public Administration, 1983; Levine and Kleeman, 1986; Volker, 1988). Mark Abramson, executive director of the Center for Excellence in Government, summed up the issue in testimony before a House committee holding hearings on creating a separate Federal Aviation Administration:

The fundamental issue facing all of us concerned about government performance is simply whether government agencies can be made to “work” within the existing system. There are many who have concluded that our existing governmental systems which include departmental oversight and the maze of personnel, procurement, and other regulations, simply does not work, and that there are certain agencies which must now be taken “out of the system” and made independent entities.

Representative Bruce Vento and Senator Bill Bradley recently introduced legislation to make the National Park Service an independent agency. Legislation has also been introduced to make the Social Security Administration and the Food and Drug Administration independent agencies. In all three cases, the reasons for “independence” are nearly identical to those cited for making FAA an independent agency—ineffective departmental oversight; a cumbersome, unpredictable budget process; and personnel and procurement regulations which impede the performance of those agencies (Abramson, 1988).

This ability of an entity to work effectively within the system is the key problem that has been raised with regard to the intramural research program at NIH. This chapter describes the committee’s findings

concerning personnel, procurement, space, travel, and administrative organization of the NIH intramural programs.

Personnel

The intramural research program accounts for approximately 10 percent of the total NIH budget, or $703 million out of $6.7 billion (NIH, 1988a). But it accounts for a majority of the NIH staff (approximately two-thirds of the total NIH full-time equivalent employment of 13,000 in fiscal year [FY] 1988). In addition, some 2,000 researchers who are not NIH employees (guest researchers, Fogarty Visiting Fellows, and scholarship recipients) also work in NIH research laboratories (NIH, 1988a; NIH, 1988b).

There are about 1,100 tenured doctoral-level researchers and 1,300 non-tenured doctoral-level researchers in the intramural research laboratories, assisted by some 2,500 support staff. In addition, approximately 3,400 employees of the intramural research program are in central support, including the Clinical Center, computer services, central supply, biomedical engineering, and central animal facilities.

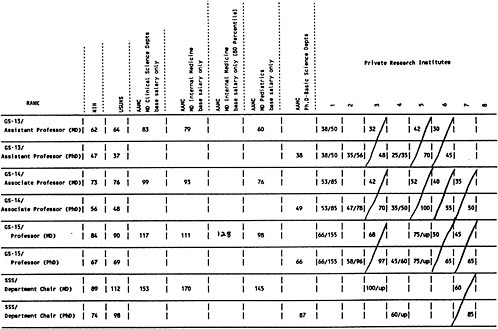

The academic core of the research program is made up of the 1,100 tenured researchers. Individuals in this group have on average worked at NIH for nearly 15 years and are in their late 40s. The majority came to NIH as postdoctoral fellows and after a period of 4–7 years were granted tenure and have remained as independent research scientists (NIH, 1988a). These scientists are employed under three different personnel systems: the General Schedule, the Senior Executive Service/Senior Scientific Service (SES/SSS), and the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps (whose personnel are Commissioned Officers [CO]). Table 3-1a describes these three systems; Table 3-1b lists the current basic pay rates for them. The salary structure between the systems is linked at several points. The ceiling on base pay for General Schedule/General Managerial (GS/GM) employees is set at the pay of Level V of the executive schedule, $72,500. (This does not affect the payment of supplemental funds such as the Physician Comparability Allowance, [PCA]). The payment ceiling for the SES (including the SSS) is Level IV of the executive schedule, $77,500 (again not including PCA). The maximum compensation that can be paid under either system is that of Level I of the executive schedule, currently $99,500.

The salary structure of the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) Commissioned Corps is more complicated because of the greater number of components that influence the pay of members of the uniformed services. Again however, base salary is limited to $77,500. Although there is no formal ceiling or cap, there are limits on the various components described in Table 3-1a, which set a de facto limit of approximately $105,000.

Compensation

The major administrative concern expressed by the senior NIH administration in papers prepared for the committee (NIH, 1988b), in congressional testimony (Wyngaarden, 1988), and as quoted in the popular press, is that the NIH salary structure is not competitive for researchers or for support staff, including nurses and allied health workers. An enduring perception of a general salary crisis notwithstanding,1 the committee found this characterization to be an oversimplification. There are marry strengths that make NIH an extremely attractive working environment for the research scientist and that help offset salary discrepancies and administrative problems. These strengths include: the relative stability in mission, funding, management, and supporting infrastructures; the Clinical Center, which provides a national model for bridging the gap between basic and clinical research; the vast array of research services, facilities, equipment, and personnel; the ability to focus full-time on research activities; the ability to conduct research that may have distant payoffs; and the freedom from grant writing.

The organization of science at NIH does not lend itself to easy answers regarding personnel strategies in terms of how resources ought to be allocated to achieve the desired complement of personnel. For example, if junior scientists were attracted to the organization by the opportunity to work under distinguished senior mentors, it could be argued that resources would best be concentrated at the upper levels. Junior scientists would accept salaries below the market rate. Some laboratories at NIH follow this model, but since outstanding mentors can be found in other places, NIH must compete for junior scientists. An alternative model is less hierarchical and one in which mid-level scientists perform the most significant part of the work. In this case, pay of senior scientists is less important, and resources are concentrated at the mid-level. This model is also found throughout NIH. In an institution with this mixture of approaches, one monolithic recruitment and retention strategy does not satisfy the organization’s needs. It is therefore important to examine the place of the intramural program in the market for each level of scientist.

The committee reviewed evidence concerning the adequacy of NIH compensation in light of the career paths for researchers and the current NIH salary structure. Because the intramural staff is so heterogeneous, the committee considered the adequacy of compensation for three groups of researchers: postdoctoral fellows (non-tenured scientists), mid-level (tenured), and senior scientists (tenured), and for support staff. The committee looked separately at compensation for M.D.s and Ph.D.s, because they are paid significantly different salaries by NIH and the private for-profit and non-profit sectors. In addition, the committee believed it necessary, in order to determine the seriousness of the compensation problem, to look at evidence of recruitment and retention problems and at comparative compensation figures.2

The committee believes evidence shows that NIH faces serious problems in recruiting and retaining senior scientists, particularly physicians, as well as various categories of support staff. The committee believes that evidence supports the concerns expressed by NIH that its salaries are not competitive for the most senior researchers, both M.D.s and Ph.D.s; that salaries are not competitive, in general, for M.D. researchers at the mid-level; and that salaries are not competitive for some support staff. Although there is overlap between Ph.D. and M.D. investigators in biomedical research, they are far from fully interchangeable. An organization whose mission includes both clinical and basic research and which operates a large research hospital cannot always substitute the less expensive Ph.D. for the physician who has alternative, more financially rewarding, career paths.

The committee finds that inflexibility in the current system of compensation causes significant problems. NIH pays higher salaries than necessary for some employees, and for other groups, lower. Its major problem appears to be that, because its salaries are tied to government-wide systems, it lacks the flexibility to respond to its special market demands.

Beginning Researchers

Employment Trends

The group of 1,300 non-tenured researchers represents the pool from which the majority of the tenured scientists are recruited.3 In reviewing Tables 3-2 to 3-6b (which provide details on this group of researchers), signs are seen of continuing strength, as well as some indication of future problems.4

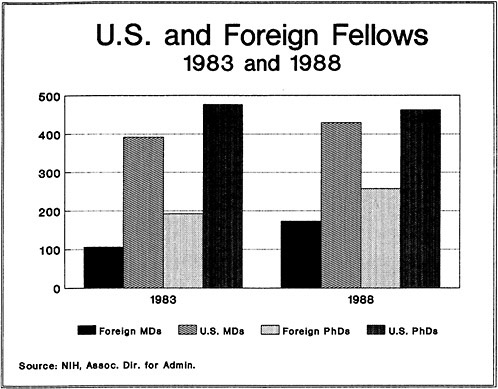

Between 1983 and 1988, the number of non-tenured researchers has fluctuated from year to year, while growing overall by 13 percent. During this period, the proportion represented by physicians held relatively stable at around 45 percent. However, the composition of the physician group changed. Foreign visiting physicians represented 21 percent of the group in 1983. By 1988 this figure had risen to 29 percent (Figure 3-1). The number of domestic physicians also increased, but more slowly. There was a shift toward entry into the Staff Fellow Program, and away from the Medical Staff Fellow Program.

Table 3-5 shows a troublesome trend in physician recruitment, as it presents data on the Medical Staff Fellowship Program and its precursor, the NIH Clinical Associate Program (Table 3-5 treats them as one). The table shows a significant decline in the number of applications distributed in 1987 and 1988, as well as a major reduction in the number completed during the period 1986–1988. These figures are consistent with the reduction in the total number of Medical Staff Fellows (Table 3-2).

The reasons for these changes are not clear. NIH may be sharing in a national phenomenon. These changes may result from the increasing indebtedness of graduating medical students, and thus their unwillingness to pursue careers in the relatively low-paying field of research; a decline in the competitive position at NIH; or a random series of events. The committee believes, however, that future trends should be watched closely, because they may represent potential problems.

Table 3-4 indicates various combinations of appointments that may be used by non-tenured scientists in the intramural program. These scientists have up to 7 years from the time they become NIH employees to the time they receive tenure. Scientists originally appointed under the Intramural Research Training Awards (IRTA) program or the National Research Council (NRC) program, because they are not technically NIH employees, have an additional 3 years before the tenure decision has to be made. Tenure can, of course, be granted earlier, and in a number of cases, particularly for those with experience before coming to NIH, tenure is granted after 4 years.5

Tables 3-6a and 3-6b provide trend data on the rate of conversion of NIH fellows to permanent, tenured positions, and thus, on the ability of NIH to renew its ranks of career researchers from within.6 These tables indicate that the average conversion rate for staff fellows, senior staff fellows, and epidemiology staff fellows has fallen from 8.3 percent during 1975–1979, to 4.9 percent during 1980–1981, to 4.2 percent in 1983–1987.

Interpreting this decline is complex. In part, it reflects the combination of how attrition rates and the FTE constraints of recent years result in few openings. Declining conversion rates may also indicate decreased ability to retain the best fellows or a sense that there are fewer outstanding scientists among the fellows.

Compensation

Table 3-3 provides information on salary (stipend) levels for NIH non-tenured researchers. Salaries range from $20,000 to $43,452 for Ph.D.s, depending on the program and the experience of the individual, and from $24,000 to $50,744 for M.D.s. Visiting scientists are also included among those without tenure, but they are fully qualified, independent researchers from foreign countries and should be considered separately.

There are some limited, comparative data available on postdoctoral salaries in other institutions. A 1987 survey of biotechnology firms shows that salaries for Ph.D. postdoctoral scientists with 1–2 years of experience average $24,180, and that salaries average $29,053 for those with 2–5 years experience (Industrial Biotechnology Association, 1987). Limited information on nationally-awarded postdoctoral fellowships from organizations such as the American Cancer Society, Damon Runyon-Walter Winchell Cancer Fund, Helen Hay Whitney, and Leukemia Society of America, show stipend levels of $20,000 for the first year, with $1,000 increments

occurring in the next 2 years. It is reported that some institutions supplement these awards with additional funds (telephone interviews, 1988). The 1987–1988 report on medical school faculty salaries indicated that Ph.D. instructors in basic science departments were paid an average of $28,000, and M.D. instructors in departments of internal medicine received an average salary of $51,000, while the average salary of M.D. instructors in all clinical departments was $60,200 (Smith, 1988). The instructor rank for medical schools is considered by NIH to be roughly equivalent to that of senior staff fellow (3–7 years postdoctoral research experience).7

Based on information available to the committee, it appears that NIH salaries/stipends for beginning researchers are roughly comparable to those paid by other organizations, such as medical schools, private research institutes, and biotechnology firms. One reason for the comparability of these salaries/stipends is that unlike salaries for permanent, tenured researchers, NIH has the authority to set stipend rates for trainees at appropriate levels because there is no government-wide salary schedule for postdoctoral researchers.

In spite of competitive salary schedules, such factors as lower conversion rates, lower numbers of applications for the Medical Staff Fellowship Program, and an increased in reliance on foreign M.D.s all point to potential problems in the future.

Mid-Level Researchers

Mid-level researchers (GS/GM 13–15 and CO 4–6), both physicians and Ph.D.s, make up the second major group of scientists in the intramural program. These are tenured, independent investigators, roughly equivalent to assistant, associate, and full professors in an academic setting. Table 3-7 provides information on NIH grades and positions, as well as the university equivalents. It is this group, along with the senior researchers, that NIH has expressed the most concern about being able to recruit and retain.

Employment Trends

The mid-level research staff increased by 6 percent between 1983 and 1988 to 991 (Table 3-8). The major increase occurred in 1984 and 1985. The percentage of physician researchers has declined slightly, from 41 percent in 1983 to a current level of 38 percent. Again, the major change occurred between 1984 and 1985 and represents an increase in the number of Ph.D. investigators rather than any marked reduction in the number of M.D.s.

Grade distribution (Table 3-8) among mid-level researchers has remained fairly constant, with the exception of M.D. researchers in the Commissioned Corps where the percentage of 00–6 officers (equivalent to an

academic rank of professor), has increased from 52 to 70 percent of the CO-04, CO-05, and CO-06s. The percentage of mid-level researchers, as a percentage of the total tenured researchers, remains above 90 percent, but declined slightly as a percentage of the total number of researchers (tenured and non-tenured), being 43 percent in 1983, and after reaching a peak of 44 percent in 1985 and 1986, declining to its current level of 41 percent.

Overall, there have been modest gains in the number of tenured, mid-level researchers during the period 1983 to 1987. These gains have occurred simultaneously with a decline in full-time equivalent (FTE) employment of all types of personnel in the intramural program from 8,729 in FY 1983 to 8,332 in FY 1987 (NIH, 1988a). The increase in the number of researchers (both in actual numbers and as a percentage of intramural employment) is due to such factors as: (1) a deliberate decision by NIH to increase the number of scientists as the budget increased, (2) vacancies in the number of support positions caused by difficulties in recruiting clinical and allied health workers because of non-competitive salaries, (3) management reviews, which convinced NIH that better organization and management could lead to a reduction of the number of positions in the Clinical Center and in research support services (ranging from procurement to central supply), and (4) the decision to contract out certain Clinical Center functions including housekeeping, food services, and escort services. Also during this period, the Clinical Center decided to contract out the departments of anesthesiology and diagnostic radiology. While this decision freed up some 35 FTEs, it was not done for this reason, but because NIH could not fill the positions at the federal salary levels. The increase in the ratio of non-tenured to tenured scientists may also represent a decision to use the former to replace difficult-to-recruit technicians—given both non-competitive salaries and strict FTE ceilings.

Attrition

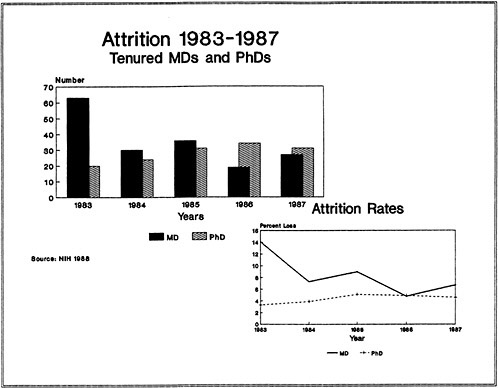

An important indicator of inadequate compensation is attrition. Table 3-10 provides information on attrition of researchers at NIH, and Figure 3-2 graphically illustrates this information over time. Overall attrition for mid-level investigators averaged 6.3 percent from FY 1983 through FY 1987. The rate was higher for physicians (8.8 percent) than for Ph.D.s (4.5 percent).

With few exceptions, such as in 1983 when more than half the CO-4 and CO-5 level physicians left, attrition rates have fluctuated between 4–9 percent both for physicians and non-physicians. There does not appear to be a trend toward increased attrition and the attrition rate compares favorably with some comparable organizations.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission between 1985 and 1987 had attrition rates among its scientists of 10 percent, 8.9 percent, and 10.9 percent respectively (personal communication with staff of Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 1988). The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in the Department of Commerce reports an attrition rate of

approximately 5 percent for its scientists and engineers, and is concerned that such a rate may be too low (personal communication with staff of NIST, 1988). A 1984 study by the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) on attrition of scientists and engineers in the SES found an attrition rate of approximately 33 percent in 7 agencies over a 5-year period (GAO, 1985). A 1987 survey of biotechnology firms shows an average turnover rate of approximately 10 percent among scientists (Industrial Biotechnology Association, 1987). Data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) show annual attrition rates of between 4 and 6 percent for Ph.D.s, and between 7.5 and 5 percent for M.D.s in U.S. medical schools between 1980 and 1985. The lowest rates for both groups occurred in 1985 (Jolly, 1986).

The committee does not believe that the attrition rate among mid-level researchers is too high. However, this does not mean that NIH may not be losing some of its best researchers. What is not known is the percentage of outstanding researchers who are leaving, or if this percentage is increasing. Indeed, the committee considered whether the 6.3 percent attrition rate, coupled with very slow growth in the NIH workforce, might not indicate problems of organizational stagnation. Like many academic institutions with a significant proportion of tenured faculty, NIH may confront difficulties in providing career growth for valued younger personnel. At the same time, such institutions will find themselves with an aging workforce.8

Recruitment to Mid-level Positions

Between 1983 and 1987 the intramural program lost some 300 mid-level researchers. These 300 were more than replaced through conversion from postdoctoral fellowships (47 percent), hiring from outside government (21 percent) (Table 3-11), and promotion, reassignment, and transfers from other parts of the government.9 Most of those recruited from outside the government were at the GS/GM 14 and 15 levels, equivalent to university associate professor or professor rank (Table 3-12). Thus, contrary to some perceptions, NIH has a mix of promotion and hiring to mid-level positions.

Compensation

It is difficult to determine how the salaries of NIH mid-level researchers compare with their counterparts in other settings, because there are few, if any, direct counterparts to NIH in the private sector. The most logical comparisons are with medical schools, private research laboratories, and private biotechnology firms. However, none of these is identical to NIH in mission, compensation, structure, or work environment. It is also difficult to know if the appropriate salary comparison is at the mean or at some other level and to know what level of comparability is necessary in order to ensure the recruitment and retention of high quality researchers.

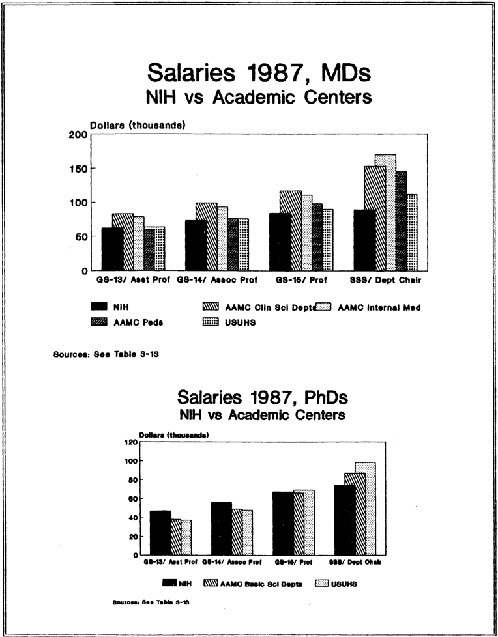

With the exception of medical schools, compensation information is relatively limited, and longitudinal data are lacking. Comparisons are also difficult because other organizations are independent and average figures hide great variations between organizations, frequently even within organizations. It is also difficult to decide which jobs are equivalent when surveys are made across positions and organizations.

Table 3-13 compares NIH salaries with a number of groups and organizations which compete with NIH for researchers.10 The picture is mixed and NIH is very competitive for researchers at some levels, while not competitive at others. Generally, NIH is more competitive for Ph.D.s than M.D.s, and more competitive at the lower grades or ranks. It is competitive with Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS) and overall AAMC averages for Ph.D.s through the GS-15/professor level, and relatively competitive with USUHS for M.D.s through the GM-15/professor level. The picture is more complex with regard to AAMC data and exemplifies the problems of making comparisons across organizations. As the table shows, the picture changes, depending on which comparison groups are used.11 However, only at the lower end of the scale (GS/13—assistant professor and, in the case of pediatricians with a base salary, GS/14—associate professor), are NIH salaries for physicians competitive. The picture with regard to private research institutes and biotechnology firms is even less clear, because there are less comprehensive data, and since many private research institutes have only a few researchers, each one is treated individually.

Several facts are apparent with regard to salaries at independent research institutes and academic institutions. They tend to have much broader pay ranges than NIH and, thus, much more flexibility in paying market rates and in meeting competition for researchers whom they particularly want to retain or recruit. This flexibility is enhanced by having the salary ranges overlap, which permits them to pay an associate professor (GS-14) more than a full professor (GS-15). Additional flexibility is provided by not having a cap or ceiling on the full professor (or equivalent) salary at many institutions. Some, though not all, of these institutions allow their researchers to do outside consulting (usually one day per week), and some share patent royalties with the researcher. With regard to biotechnology firms, not only is it difficult to judge comparable jobs, but salary information is treated as highly confidential.

Data from a 1987 survey of more than 130 biotechnology firms also provides useful salary information on 4 categories of Ph.D. researchers:

-

Scientist I, 0–2 years after completion postdoctoral experience, receive an average salary of $37,000.

-

Scientist II, with 2–5 years postdoctoral experience receive an average of $43,000.

-

Scientist III, with 5–10 years postdoctoral experience receive an average salary of $50,000.

-

Scientist IV, with more than 10 years postdoctoral experience receive an average salary of $58,000.

In addition, approximately 20 percent of the scientists in the first category were eligible for incentive packages totaling 4 percent of base salary. This increased to 55 percent of the scientists in the fourth category, where incentive packages averaged 7.3 percent of base salary.

The same survey showed that annual salaries for senior clinical researchers (M.D.s), positions roughly comparable to the GS-15 level at NIH, averaged $96,000 (Industrial Biotechnology Association, 1987). Based on this relatively limited data, it would appear that NIH salaries for mid-level Ph.D. researchers are comparable to those paid by the biotechnology industry and that NIH salaries for M.D.s trail by approximately 10 to 20 percent.

The National Science Foundation (NSF) survey of doctorate recipients provides additional information on the competitiveness of NIH salaries for Ph.D. researchers. The survey contains a representative sample of more than 50,000 doctorate holders in the United States. The sampling rate for those disciplines employed by NIH is approximately 1 in 10. It is a longitudinal survey with the sample re-interviewed every two years.

Table 3-14 shows the 1981 and 1987 salaries of researchers employed at NIH in 1981; those who remained at NIH received an average 1987 salary of $54,500, while those who left averaged $60,564. Additional detail from the survey, which shows salaries of individuals in the upper quartile, indicates the impact of the federal salary cap, with NIH salaries clustering between $66,000 and $75,000, while salaries for those who left NIH range from $70,000 to $100,000 (Michael Finn, Office of Scientific and Engineering Personnel, National Research Council, communication to committee, 1988).

Table 3-14 does not document large disparities; it does indicate, however, that NIH salaries for Ph.D.s (at least for those with multiple opportunities) have not kept pace with the private for-profit and non-profit sectors. Also, because of salary ceilings and resulting pay compression, NIH is the least competitive for the most senior scientists. The numbers in the sample are very small, but the findings are consistent with other information.

It should be noted that Table 3-14 includes both mid-level and senior Ph.D. researchers. Based on the distribution of salaries, it appears that disparities are greater for senior researchers than the larger group of mid-level researchers.

Another important issue is how NIH salaries compare with those of other organizations over time. For this comparison, the best source is AAMC data on medical school salaries. Tables 3-15 and 3-16 show mean NIH compensation as a percent of mean AAMC compensation for Ph.D.s in basic science departments and M.D.s in clinical science departments. These tables show that for mid-level researchers, both M.D.s and Ph.D.s, NIH compensation has fallen compared to that of researchers in medical schools. For M.D.s, the decline has been between 9 and 10 percent, depending on the grade; for other doctorates, it has been between 11 and 14 percent. There does not appear to be any particular pattern with regard to grade within the ranks of mid-level researchers, i.e., from lower to higher or vice versa.

In sum, the data on recruitment and retention (attrition rates, conversion rates, number of individuals recruited from outside government, etc.), of mid-level researchers do not show evidence of major problems for either M.D.s or Ph.D.s. With regard to salary comparability, the information is somewhat more mixed (Figure 3-3). Comparing average salaries, NIH would appear to be competitive for a researcher holding a Ph.D. degree. There is limited evidence that Ph.D. researchers who leave NIH receive higher salaries than those who remain. Data on salaries paid by academic institutions, independent research institutes, and biotechnology firms indicate that broader overlapping pay bands provide these organizations much greater flexibility in compensating their mid-level researchers. The committee finds that this lack of flexibility, rather than any overall lack of salary competitiveness, provides NIH with its greatest difficulty in retaining mid-level Ph.D. researchers. Such flexibility might include, in special cases, the ability to pay above the pay band (or the provision of broader or overlapping pay bands), the ability to pay above the cap (currently $72,500, $77,500, or $99,500, depending on grade level and degrees), the authorization of recruitment and retention bonuses, or accelerated hiring or promotion procedures.

With regard to physician researchers, there is a pay disparity above the lowest ranks of mid-level researchers. A slightly lower percentage of physicians among the tenured researchers and a rapid increase in their age suggest that the salary disparities may be causing recruitment and retention problems. Again, however, the committee does not believe the evidence justifies significant overall salary increases. As with Ph.D. researchers, the committee believes that the major problem relates to the lack of flexibility in the current salary system, which prevents NIH’s recruitment or retention of individuals particularly important to its programs.

Senior Researchers

Much of the concern, especially in the lay press, over the loss of scientists at NIH has focused on senior researchers—the scientific superstars. Senior scientists (SSS and CO-7, and some GM. 15 and CO-6),

constitute about 8 percent of the permanent scientific staff of the intramural program. The group, which includes laboratory chiefs and the scientific directors of institutes, is equivalent to professor-level and above in a university. Between 1983 and 1988, the total number of senior researchers has fallen approximately 10 percent, from 95 to 86, and physicians as a percent of total senior staff have fluctuated between 30 and 33 percent.

Attrition

Attrition among all senior researchers averaged 3.4 percent a year between FYs 83 and 87; percentages for M.D.s and Ph.D.s were 3.8 and 3.2, respectively. As expected, given the small numbers involved, there was considerable variation by year, but no apparent trend.

Although attrition rates are quite low, replacements represent a problem. Fifteen senior scientists left NIH during this period and six had been replaced as of May, 1988—all by promotion from within. In fact, NIH has not recruited anyone to the SSS from outside the organization since its creation. This contrasts sharply with the fact that 105 mid-level scientists were brought in from outside government during the 5-year period 1983–1987.12

The average age and length of experience increased for these senior researchers. Between September 30, 1983 and May, 1988 the average age of Ph.D.s in the SSS increased from 56.9 years to 59 years, and the average years at NIH from 21.6 to 24.7. The increase in average age for M.D.s has been less dramatic, from 57.4 to 58.4, however, the average length of experience at NIH has increased from 15.8 years to 19.4 years.

Table 3-10 shows that the Ph.D.s are leaving at normal retirement age (mid-to-late 60s), while M.D.s, with some exceptions, are leaving in their early-to-mid 50s.

Compensation

Tables 3-13 to 3-16, Figure 3-3, and the survey of biotechnology firms, provide comparative information on the salaries of senior research scientists. When compared with those of the USUHS, medical school faculties, or senior researchers at private research institutes, NIH salaries are significantly lower. This is true both for M.D.s and Ph.D.s, although the disparity is greatest for researchers with M.D. degrees.

The problems of comparing salaries across different organizations is highlighted in trying to find proper groups against which to compare senior NIH researchers. As has been noted, NIH has for many years compared members of the SSS with medical school department chairmen. While it seems reasonable to do this with regard to some members of the SSS—division directors, scientific directors, some laboratory chiefs, it

is not clear that the comparison is appropriate for all members of the SSS. While all of the members of the SSS have managerial and policy duties, their levels of responsibility vary significantly.

To have the widest range of comparisons, the committee compared members of the SSS with department chairmen (Ph.D.s with Ph.D. chairmen of basic science departments and M.D.s with M.D. chairmen of clinical science departments); it also compared M.D. members of the SSS with chairmen of departments of internal medicine and pediatrics (thus eliminating high paying medical school departments, such as anesthesiology and radiology, which lack NIH counterparts); and it compared M.D. members of the SSS with full professors at the 80th percentile. Even with these more limiting comparisons, the gap between NIH salaries and those in medical schools is still significant at the level of SSS.

Tables 3-15 and 3-16, comparing NIH salaries with basic science and clinical science chairmen, show that the gap has widened over time. For example, in 1983, senior Ph.D.s at NIH received salaries comparable to those of the chairmen of basic science departments. By 1988, they were paid an average of 83 percent of what department chairmen received. The disparity for M.D.s increased an additional 10 percent during the same 5-year period.

One reason for this lack of competitiveness is the federal salary cap. Table 3-14 shows changes in average annual salary for Ph.D.s working at NIH in 1981 and in 1987, as well as the changes in salary by type of employer for those who left NIH. Senior scientists employed by universities/medical schools had average salaries above the maximum allowed by the federal salary cap. That table, which includes both mid-level and senior-level Ph.D.s, indicates that researchers employed at NIH in 1981, but who left there prior to 1987, earned higher average salaries than their counterparts who remained. Private research institutes generally have no fixed upper limit and frequently offer salaries over $100,000.

While comparative data are quite limited at this level, it would appear that total compensation offered by biotechnology firms also exceeds the compensation that NIH can offer. Additional insights are shown by examples of key individuals NIH lost between 1983 and 1988.13

The reduction in the number of senior researchers, the increasing age of those remaining, the failure to successfully recruit from outside, and the evidence of generally noncompetitive salaries justifies NIH concerns about their future ability to recruit and retain senior researchers and research administrators. This is particularly serious since many of the current researchers are approaching retirement age. Again, as with the mid-level researchers, the problem is lack of flexibility within the current personnel system. This problem is exemplified by the federal pay cap ($77.5 thousand in base salary, $99.5 thousand total salary).

Personnel losses are not inherently bad. In fact, a function of NIH is to develop researchers, who will leave to create programs of excellence elsewhere. When senior intramural researchers leave, new researchers have a chance to develop and became the next generation of superstars. However, if losses became abnormally high, or if quality replacements cannot be developed, an organization faces decline. The question is one of balance, of enough turnover to allow new blood without diluting quality. The committee believes that NIH’s primary concern should broaden from the loss of senior researchers to its capacity to revitalize at all ranks.

Support Staff

Salary problems also affect research support staff, particularly secretaries, nurses, and allied health workers. Interviews with NIH staff produced repeated discussions of problems in recruiting and retaining secretaries and technical support personnel.14 One institute scientific director said “nothing can cause a good laboratory to break down faster than the loss of a top-notch lab secretary—the glue that holds the place together” (NIH staff interviews, 1988). Others complained of difficulty and delay in filling vacant positions and of recruiting qualified applicants. For example, concerns about a number of occupations are expressed in the recent Report of the NIH Directors Task Force on the Shortage of Nurses in the Clinical Center. With regard to allied health workers the report states:

The present salary and benefits package for Allied Health Personnel is far below the compensation offered by neighboring hospitals. Area hospitals are paying salaries that range from 11 percent to 28 percent higher than that being paid by the Clinical Center. This has resulted in extraordinary vacancy and turnover rates…. After examining this data, the committee recommends that a legislative amendment be vigorously pursued that extends the Title 38 pay and benefit options to Allied Health Care workers (NIH, 1988c).

Table 3-17 provides salary comparisons between NIH and eight major Washington area hospitals for selected allied health professions. It is reported that the difficulties with medical technologists and phlebotomists are of recent origin. This again points up the problems NIH faces because of its rigid salary structure and the extended time involved in making changes.

The current situation involving nurses is more positive than it has been in recent years. Significant shortages, beginning in 1983, led to the passage of legislation that allows NIH to employ nurses at the Clinical Center under the authority of the Veterans Administration Title 38, which authorizes the setting of competitive pay rates. The following excerpts from the Director’s Task Force Report summarizes the situation over the last several years:

In 1983, the Clinical Center experienced the first significant impact of what was to become a major crisis in nursing. Significant problems were encountered in staffing the medical oncology service of the Cancer Institute, subsequently necessitating the closing of 20 of the available 40 beds for that activity. Problems in recruitment and retention of oncology nurses were felt to underlie this shortage, and were attributed by the nursing service to the stresses of oncology nursing, as well as the noncompetitive salaries offered by NIH. The nursing shortage led to a number of consequences which adversely affected clinical research: a halt to new patients accession to protocols, “boarding” in-patients on non-cancer wards, and a slowing of implementation of new protocols for cancer and AIDS. Similar shortages subsequently affected the staffing of a number of other services at NIH, and forced curtailment of clinical research utilizing the surgical intensive care unit and the medical intensive care unit, as well as patient admissions for cardiac surgery, neurosurgery, mental health, and AIDS…. (NIH, 1988c).

The current pay system for nurses, which allows the U.S. Assistant Secretary for Health to set competitive salaries, is an example of the type of flexibility that the committee believes NIH needs to continue to function effectively.

Summary of Compensation Findings

Based on its analysis of compensation of individuals in the intramural research program at NIH, the committee finds that:

-

Government-wide salary ranges are not competitive for either M.D. or Ph.D. researchers at the most senior levels (SSS, C0-7) or for physician researchers above the beginning middle levels (GS-13, CO-4). Salaries are, however, competitive for junior scientists, and Ph.Ds at the mid-level.

-

Over the last -157- years, NIH salaries have not kept pace with salaries in the nation’s medical schools.

-

Significant pay problems exist, or have recently existed, with regard to secretaries, nurses, allied health workers, and other technical support personnel.

-

The government personnel system does not have the flexibility to adjust salaries to meet specific needs in a timely manner without increasing all salaries.

-

There have been losses of significant researchers and major difficulties in recruiting replacements at the senior levels (SSS, C0–7).

The Personnel System

The personnel system includes all laws, rules, regulations, and procedures involving recruitment, maintenance, payment, promotion, and retirement of employees. The system deals with rates of pay, fringe benefits, position classification, employee evaluation, awards, and a myriad of other details. The previous section focused exclusively on that part of the personnel system dealing with compensation; this section deals with all other aspects of the system.

Impediments Created by Externally Controlled Personnel Systems

The employees of NIH are largely governed by three personnel systems: the GS, the SES/SSS, and the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps (Table 3-1a). These three systems are all controlled by organizations beyond NIH (Commissioned Corps by the Public Health Service, and the GS and SES/SSS by the Office of Personnel Management [OPM] and DHHS). They are general systems designed to meet the needs of a wide variety of organizations and, therefore, tend to value uniformity and consistency over flexibility and innovation. The major problems with the current systems, as described by NIH staff, are slowness and lack of responsiveness to the needs of NIH as a research organization.

One measure of this slowness is the length of time it takes to appoint a scientist to a senior position. In the past year, NIH completed 24 appointments into the SES/SSS or equivalent positions in the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. Six cases were in the SSS, all of which were promotions for scientists who were already at NIH. The average processing time for both promotions from within the NIH and appointments from outside, was approximately 8.5 months (NIH, 1988a).15

Another example of the problem with an externally controlled personnel system is shown by recent occurrences within the USERS Commissioned Corps. Policy for the corps is determined by the Surgeon General. In 1987, the Surgeon General decided to “revitalize” the corps by measures which many scientists find unsuited to the environment in which they work. These measures included: (1) rotational assignments, (2) wearing uniforms and practicing military courtesy (saluting), (3) reduction of the number of senior officers, and (4) strict enforcement of the 30-year mandatory retirement policy. Some 34 senior scientists at NIH, including the Deputy Director for the Clinical Center and a number of Branch and Lab Chiefs in the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), received letters of mandatory retirement. After negotiations, the Surgeon General withdrew the letters; however, concern and some bitterness remains (Havermann, 1987; Specter, 1987; Kosterlitz, 1988).

The current SES/SSS system also provides examples of problems:

-

The Office of the Secretary of DHHS has to approve each SES/SSS appointment.

-

The Chief of Staff of DHHS required the Director of NIH to reduce the performance ratings of a number of NIH SES members, because he believed too many had been rated outstanding (although he did not require changes for members of SSS).

-

The Secretary’s office makes the decisions on which NIH SES/SSS members receive bonuses.

-

The operation of the SES, of which SSS is a sub-part—from appointments, to the development of work plans, to rewards—is based on the assumption that its members are managers. Therefore, the rules enforced by DHHS and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) require that scientific work be made to appear managerial.

Other examples of personnel system problems include the following:

-

To recruit employees from outside of government, NIH must request a “panel of eligibles.” This panel comes from OPM through the PHS and DHHS. It is reported that by the time this can occur, most people on the list have either moved from the area, found other jobs, or are no longer interested.

-

When the law was enacted authorizing the Veterans Administration pay system to be used for nurses at the Clinical Center, the Secretary’s office delegated the

-

authority to set pay levels to the Assistant Secretary for Health. Currently, the PHS has not approved the NIH request to re-delegate the authority to the Director of NIH (NIH, PHS, and DHHS, staff interviews, 1988).

FTE Ceilings

Another major concern about the personnel system is the mandated external limitation on the number of full-time equivalent personnel. Nearly all executive branch employees are under the President’s Employment Ceiling, controlled by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). The OMB allocates FTEs to DHHS, which in turn subdivides its ceiling to the PHS, which further subdivides its ceiling between various health agencies, including NIH (NIH, 1988a; OPM, 1988). Since NIH is a part of the PHS and since the PHS has been over its ceiling, NIH has been prevented on many occasions from hiring people from the outside.

An FTE ceiling—in addition to an overall budget constraint—creates unnecessary problems, especially when there is little or no growth, low attrition rates, and constraints on the ability to remove less productive personnel. The effect of these problems on the quality and efficiency of the intramural program is difficult to assess, but the committee was convinced that effective management is inhibited.

A 1985 review of Clinical Center management issues presents some examples. The limitations on FTEs in intensive care units caused a 25 percent under-utilization of surgical units. The new ambulatory care unit faced severe problems in meeting both patient care and clinical research needs because of a shortage of FTEs. Clinical Pathology had to make the decision on whether to conduct laboratory tests in-house or contract them out, based not on appropriateness or minimizing costs, but on the availability of FTEs (NIH, 1985a). Problems in hiring technicians provide an example of the impact of FTE ceilings outside the Clinical Center.16

The overall effect of FTE ceilings that grow more slowly than budgets is that managers who are best placed to make decisions about how to allocate money to fulfill congressional mandates, are prevented from making the most productive decisions.

Retirement

Another problem with the current personnel systems relates to retirement programs. Although NIH retirement programs are generous, they are not integrated with Teachers Insurance Annuity Association-College Retirement Equities Fund (TIAA-CREF) and other systems found in universities and medical schools making it extremely difficult to recruit people to NIH from academic settings. Senior DHHS and NIH officials estimate that, if the retirement systems could be made compatible, it would be much easier for NIH to recruit qualified researchers from the

outside without additional costs to the government (NIH, staff interviews, 1988).

The retirement system of the commissioned corps also creates difficulties. This non-contributory system requires an individual to serve for a least 20 years in order to receive any retirement benefits, but mandates that they retire after 30 years. These provisions have both good and bad sides. The 20 years rule is a powerful incentive to remain in the organization. The 30 year rule can result in the loss of scientific leaders.

Barriers to a Productive Work Environment

In addition to the personnel system, there are a number of other barriers that hamper NIH in accomplishing its research mission. Some of these are government-wide, others relate to NIH’s location within DHHS, and still others are internal to NIH.

Recruitment and retention of staff are made more difficult by the generally low regard in which federal employees are held, both by the general public and by politicians. Both actions and rhetoric of recent administrations have had a negative impact on the federal work force. The current administration proposed a number of measures that would have adversely affect government workers—ranging from a proposed pay cut of 5 percent in 1986, to drastic cuts in retirement benefits, to increasing the retirement age from 55 to 65.

These issues are summed up in a paper entitled, The Federal Civil Service At the Crossroads, prepared for a conference on “A National Public Service for the Year 2000,” jointly sponsored by the Brookings Institution and the American Enterprise Institute:

…a growing perception among federal employees is that they are under-appreciated and under-rewarded which is affecting morale and quality of the work force at the entry level, among shortage groups, and at senior levels. The consequent erosion of the human resource capacity of the federal work force is an expected outcome of this process and raises a large question about what the future civil service will be like (Levine and Kleeman, 1986).

These attacks on federal employees have had a negative impact on NIH employees and have reduced their traditional esprit de corps. In addition, numerous recent battles with DHHS have taken a toll on NIH morale. In many ways the issue is summed up by the senior official in DHHS who said, “HHS likes to think it’s a Department while NIH thinks it’s special and wants to be treated differently” (NIH and DHHS, staff interviews, 1988).

Currently, NIH is one of a number of operating agencies under the PHS, which in turn is one of a group of operating divisions under DHHS. Also under DHHS structure are a number of Staff Divisions, each headed by an Assistant Secretary or the equivalent (Budget, Personnel, Legislation, Planning and Evaluation, General Counsel).

NIH has expressed the viewpoint that its organizational location creates many of the administrative barriers it faces, and that these barriers limit its capacity to achieve its mission. Even small administrative innovations can be approved only after the large and proliferating layers of bureaucracy have been persuaded. Because mid-level bureaucrats are afraid to make mistakes in interpreting guidelines and rules, decisions are bucked up from one layer to the next, a process that can take months or years.

Administrative barriers are imposed on NIH by staffs that are constantly changing and are far removed from the dynamics of biomedical research. NIH is needlessly harmed in many ways because the Director of NIH often cannot accomplish his business with the Secretary of DHHS directly and decisively (NIH, 1988b).

Space

Many of those who responded to the committee’s request for information commented on the poor laboratory and office space available to NIH scientists.17 ‘They remarked that this added to the intramural program’s difficulties in retaining and recruiting staff. There is significant variation among the institutes in allotment of laboratory space per individual researcher. This would be expected, based on the differing types of research conducted, but also probably reflects luck and the timing of each institute’s creation. In a 1985 study of a proposed building for the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), it was reported that, based on a 1983 space survey, NICHD scientists and support staff had an average of 141 square feet per person. The comparable figure for all institutes was 240 square feet (NIH, 1985b). Figures from a December 1987 space survey indicated that the average figure for all institutes has decreased to 172.3 square feet. The figure for NICHD was still the lowest, 120.4 square feet. The highest square foot figure was in the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS) at 192.5, with NHLBI having 173.4 square feet, and NIAID having an average of 163.1 square feet per person. These figures represent NIH laboratory space in the Washington metropolitan area; figures for field stations are somewhat higher. Overall, NIH has slightly more than 700,000 square feet of laboratory space and 300,000 square feet of laboratory support space in the Washington area (NIH, 1987).

The problems of space have not been ignored, but improvements have been slowed by bureaucratic delays. It is estimated by NIH that construction of the new neurosciences/primate facility was delayed for nearly a year because of continuing PHS review and re-review. It is estimated that all construction or major renovation is delayed for 6 months to a year because of PHS reviews. The major renovation of the oldest laboratory buildings, called the round-robin renovation, was originally scheduled for completion in FY 1991, is expected to run until 1997. NIH officials attribute the delays to a combination of unnecessary PHS reviews and problems with appropriations. NIH staff are also bothered by what they consider PHS interference in day-to day operations. One example was that all easements—even routine ones, such as for the gas and electric companies, and even at field stations, such as those in North Carolina—have to be reviewed and signed by the PHS (NIH staff interviews, 1988).

The adequacy of current laboratory facilities is difficult to judge. Most PHS and DHHS managers interviewed believe the space to be adequate, and they point out that overcrowding is caused, in part, by the tendency of NIH to find ways around the FTE ceilings. The committee is unable to answer the question of the degree to which space problems are caused by NIH’s unwillingness to set priorities and to discontinue or curtail programs and projects that are less successful.

In sum, it would appear that, based on current research programs being conducted at current levels, space is inadequate for a number of institutes and conditions have deteriorated in recent years. (Approved new construction will provide some relief with the addition of 95,000 square feet of laboratory space on campus by FY 1991 [NIH staff interviews, 1988]). Some space problems can be attributed to bureaucratic layering (and in one instance, delays more than doubled the cost of the project), and a lack of sympathy on the part of administrative people not knowledgeable about research, while other major problems include the governmental budgeting process and the political difficulties in obtaining authorization for construction in the Washington metropolitan area.

Travel to International Conferences

Even minor bureaucratic impediments can cause frustration. Such appears to be the case with regard to travel to international conferences. DHHS centrally controls the travel of its employees to meetings in foreign countries. These controls are applied even if the agency has adequate funds to pay for the travel. This decision to control international meeting travel is not mandated by law, regulation, or outside agencies such as OMB (NIH, 1988a; NIH staff interviews, 1988).

The ceilings have not kept pace with inflation and the vastly decreased purchasing power of the dollar. From a public management perspective, it is hard to justify DHHS’s disposition of a ceiling on

international meeting travel, rather than holding line managers accountable for prudent use of resources that have been allocated to them. It is even harder to rationalize the current system when, not only a ceiling is imposed, but individual trips for staff at the SSS level have to be approved by the Secretary’s office.

While no standards or comparisons are available, it is generally believed by the scientists that research is hampered by their inability to send appropriate numbers of scientific researchers to international meetings.

Procurement

The general issue of government procurement has been a bane to everyone involved for many years. Contractors argue that the government is slow in processing requests, vague in its requirements, and even slower to pay its bills. Government employees needing materials complain that the process is cumbersome, laborious, and inflexible. Congress and the general public view the system with cynicism and distrust. Second only to agencies asking for relief from the government-wide personnel system are those seeking exemption from the dreaded Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) (Abramson, 1988; Aviation Safety Commission, 1988).

While NIH scientists feel that they, and the nation’s biomedical research effort, are well served by existing procurement practices, there is some concern in the Inspector General’s office of DHHS about the level of accountability and full compliance with existing regulations (DHHS, 1988). These concerns, together with recent Defense Department procurement scandals seem likely to stimulate an increased level of regulation of procurement policy. Existing procurement procedures at NIH are supportive of the research effort and provide little justification for considering privatization of the intramural research program. NIH has expressed the specific concern that excessive statutory restrictions on procurement would severely thwart the flexibility necessary to make effective use of the nation’s investment in biomedical research. Although the committee shares this concern, we believe that appropriate levels of accountability can be achieved, with due allowance for the need of an effective research program, and that privatization is not a serious alternative solution to this problem.

Summary

There is evidence that many good scientists are willing to forgo much higher earnings to enjoy the distinctive research environment at NIH, which for some, is especially conducive to research productivity and creativity. But some of the factors that contribute to this environment are subject to counterproductive, administrative controls. Notable among these are travel, support personnel, equipment, space, and procurement.

Although there is little evidence that the PHS or DHHS interferes with scientific direction at NIH, the cumulative impact of not being able to fill technician positions, of delays and endless paperwork in getting promotions, of the crowding and overall lack of space, and of a perceived lack of respect, is having a negative impact on the scientists, if not directly on the quality of the science.

The combination of increasingly burdensome and unnecessary constraints with lower salaries and less flexible administrative policies creates concern about NIH’s ability to build the future staff necessary to sustain the quality and vitality of the intramural program.

Coping With a Changing Environment

In addition to administrative problems caused by the subordinate organizational location of NIH, concern has also been expressed about the authority of the director to meet organization-wide responsibilities and his ability to marshal resources to plan for the future, and to respond to crisis situations and external demands.

NIH indicates that part of the problem is that the director lacks the authority to reprogram funds and to establish and administer a flexible reserve fund. The 1984 IOM study of the organization of NIH confirmed that the Director of NIH had relatively limited authority vis a vis individual institute directors. As that report stated, “authority in the NIH has became increasingly decentralized over the years for a number of reasons. The institutes have became more autonomous, with their own congressional appropriations and their own specific constituencies.” Lacking budget authority, including any ability to reprogram funds to meet emergencies or opportunities, and lacking a reserve fund, it is very difficult for the director to plan and coordinate activities across institutes.

A review of previous studies of the intramural program conducted for the 1984 IOM study also identified other concerns. These included the need to review the Medical Fellows Program to ensure high quality in all institutes and the need to make managerial practices more flexible and responsive to outside initiatives. The decentralized nature of the intramural programs was said to make it difficult to coordinate NIH-wide or DHHS priorities. The decentralized appropriation structure and autonomy of the institutes often make it difficult to shift resources to respond to scientific opportunities, congressional concerns, and NIH or secretarial directives (IOM, 1984).

This lack of responsiveness may sometimes be attributable to a structure that inhibits comprehensive and decisive response. For example, NIH has received mixed reviews about its response to the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) crisis. Many analysts have given them

good marks, but others have criticized NIH for one or more of the following failures: slowness to recognize the extent and seriousness of the problem; failure to mobilize resources; failure to coordinate the responses of various institutes; and, lack of cooperation among institutes, Centers for Disease Control, and the outside research community (Panem, 1988; Stoto et al., 1988; Shilts, 1988).

In looking to the future of the intramural program, the committee found it necessary to assess the environment in which the program will operate. A number of factors indicate that today’s problems are likely to be exacerbated. The demand for biomedical researchers is likely to continue to grew. The evolution of science is blurring interdisciplinary boundaries, and moving quickly in unpredictable directions. In addition, as the AIDS epidemic indicates, health emergencies occur and the strengths of individual institutes may need to be mobilized in a coordinated undertaking. Acknowledging these problems, the President’s Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic (AIDS Commission), made a number of recommendations to improve the ability of NIH to respond to the AIDS crisis (Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic, 1988). Major commission recommendations include giving the Director of NIH increased authority over budget and personnel resources within NIH for a 2-year period and having him report directly to the Secretary of DHHS.

To move effectively in areas over which no one institute has a logical claim, NIH needs a capability to make and implement decisions that transcend institute lines. This capability does not exist today. The challenge is to address this problem without undermining the strengths of the current structure of independent institutes that form a confederated NIH.

Summary of Administrative Problems

The committee concluded that personnel problems, both those relating to compensation and the overall personnel system, are compromising the ability of NIH to recruit and retain scientists of the highest quality. The committee found that, in selected areas, NIH salaries are not competitive, particularly for physician researchers and overall for those at the most senior levels. Although federal salaries in general lag behind the private sectors, this is less of a problem for NIH than the fact that the system lacks the flexibility necessary to compete in a tight labor market. While the committee would like to see appropriate pay compatibility for federal workers, and hopes that the efforts of the Quadrennial Commission and the Volker Commission will be successful,18 it is convinced that it is also important for NIH to have the flexibility necessary to compete for key individuals and necessary categories of support personnel.

Administrative problems are not so serious as to require drastic changes. However, they are serious enough to require consideration of a greater delegation of authority to NIH from DHHS and the PHS. Vigilance is needed to assure that these administrative problems do not reduce the

traditional esprit of NIH to the extent that it is no longer able to retain its large pool of dedicated researchers. The committee finds that, taken as a whole, these problems call for action on the parts of Congress, the Department of Health and Human Services, and the National Institutes of Health. The question for discussion in the next chapter is what type of actions, structural or specific, make sense given the scope and nature of the problems.

ENDNOTES

|

|

1. Serious concern over NIH salaries has been expressed in many reports, including the report of the President’s Biomedical Research Panel, (1976) ; The Federal Laboratory Review Panel (Packard Committee) 1983; and two internal NIH committees, the Committee on Pay and Personnel Systems in Intramural Research (Eberhart Committee), 1981 and the Committee on Pay of Scientists (Chen Committee), 1982. |

|

|

2. The issue of quality makes this assessment more difficult. NIH not only requires the ability to employ an adequate number of investigators, but these investigators must be capable of performing independent research of high quality. Chapter 2 addresses the issue of quality at NIH and indicates that, while the committee believes that the intramural program is one of the nation’s important centers of biomedical science, it is unable to determine how deeply the highest level of quality pervades the organization. While there is significant evidence of scientific excellence, the committee believes that further improvements in quality can be maintained only if the pool of scientists remains strong. |

|

|

3. Table 3-3 provides more detailed information on all programs used to recruit non-tenured scientists for the period 1983–1987. Because the Medical Staff Fellow Program, which began in 1981, lasts for 3 years, the first conversions occur in 1984 (Table 3-6b). The rate of conversion has been relatively low—ranging between 1 percent and 3.6 percent, with the lowest rates occurring in the last 2 fiscal years. (However, a number of M.D.s progress from the Medical Staff Fellowship Program to the Senior Staff Fellowship Program before being considered for tenure). Most conversions are from the Senior Staff Fellowship Program, individuals with 3–7 years postdoctoral experience, and are made at the GS/GM-13 level. A few conversions, primarily M.D.s, are made at the GS/GM-14 level and a few are made into the Public Health Service Commissioned Corps—normally at the CO-3 or CO–4 levels. The reduction in the number of fellows going into the corps in the last two years is probably attributable to both changes in corps assignment patterns, which make it less desirable for someone interested in a biomedical research career, and to the elimination of the clinical associate program. |

|

|

4. References to physicians or M.D.s in the tables and text include M.D.s, doctors of osteopathy (D.O.s), and those M.D.s and D.O.s who also have a Ph.D. References to Ph.D.s in the tables and text include small numbers of individuals with other doctorates. These include dentists, veterinarians, podiatrists, and those with doctoral degrees in fields, such as pharmacy and public health, and those with equivalent foreign degrees. |

|

|

5. There is a fundamental difference in the meaning of tenure between NIH and academia. In universities, the tenure clock does not begin to tick until the faculty member has completed postdoctoral training and has been given his/her initial faculty appointment. In contrast, at NIH, the clock begins to tick at the time the individual enters into postdoctoral training. As Table 3-4 describes, for some researchers who begin their postdoctoral careers at NIH, the time to tenure may extend up to 10 years; however, this is not true for the majority of researchers. NIH does not currently have information of the average time it takes to receive tenure. Some senior staff members estimate the average is 7 years, while others believe it is closer to 4 years. The committee suggests it would be useful for NIH to review systematically its actual experience with tenure. In general, in making comparisons between NIH and universities, it is important to remember that the GS-13 senior investigator position at NIH is tenured, while the assistant professor position at a university is not. |

|

|

6. Several peculiarities pertaining to these data should be noted. The conversion rates appear artificially low, because the NIH personnel data system does not have the ability to track a cohort of new appointees through the system until they receive tenure or leave NIH. The conversion rate shown is, therefore, a synthetic one derived by dividing the number converted during a given fiscal year by the total number of fellows on board at the beginning of that fiscal year. Because fellows are employed for a number of years, it is likely that the true conversion rate is significantly higher. In addition, most visiting associates and visiting scientists, because they are foreign nationals, are not eligible for permanent appointments at NIH. In spite of these caveats, the data provide useful insights into the ability of NIH to retain younger researchers. This is particularly true for the trend data for staff fellows, including senior staff fellows, because comparable data are available for most years back to 1975. |

|

|

7. This comparison must be used with caution, since the definition of instructor varies considerably among medical schools, and therefore lacks internal consistency. Most basic science departments do not use the title, but instead activate a faculty members initial appointment as assistant professor. In many clinical departments, the title is used for clinicians and not researchers. With these cautions, the information does allow another limited comparison of the competitiveness of NIH salaries for beginning researchers. |

|

|

8. The intramural program mid-level workforce is indeed aging. The average age of physicians went from 42.8 years in 1983 to 45.6 years in 1988, and Ph.D. scientists went from 46.1 years to 47.6 years over the same period. There are a number of potential explanations for these changes; the overall |

|

|

U.S. population and the overall federal workforce is aging. The average age of both M.D. and Ph.D. faculty in U.S. medical schools has increased slowly for a number of years (Jolly, 1986). Besides these general considerations, there are specific programmatic factors that may effect the increasing average age of researchers at NIH (especially M.D.s). As Table 3-8 shows, there is a significant reduction in the number of M.D.s in grades C0-4 and C0-5, and a major increase in the number of C0-6s. This probably is caused by phasing out the Clinical Associates Program, which recruited people into the corps, and its replacement by the Medical Staff Fellowship Program, which recruits into the Civil Service. The change may be accounted for, in part, by the creation of new fellowship programs, such as IRTA, which allow researchers to spend up to 10 years at NIH before they receive tenure. This is important to the issue of age, since the changing age distribution is based on permanent staff, and does not include fellows. Data on researchers who left NIH (Table 3-9) show much less clear direction, especially for physicians, possibly representing the fact that the much smaller numbers are more subject to random events. In some years, the average age of physicians leaving NIH has been younger than those remaining and in some years, older, with no discernible trend. The same is true with regard to their years of experience at NIH. With regard to Ph.D.s, although the average age at departure has fluctuated with no specific trend, those leaving have been significantly older each year than those who remain. The reasons for, or the impacts of, the aging of the research scientists are not clear; the magnitude of the shifts, particularly with regard to physicians, warrants continued monitoring and analysis by NIH. |

|

|

9. Included in this group are 32 individuals (GS-13 to -15) originally brought to NIH from outside on special time-limited appointments, and then converted to permanent positions. |

|

|

10. The complexities of making comparisons across organizations increase significantly when the attempt is made to compare total benefits (base pay plus bonuses, allowances, retirement benefits, health insurance benefits, life insurance benefits, and leave benefits). The Office of Personnel Management uses the figures 23–26 percent of base pay as the value of the benefit package for the general federal workforce. A representative of the American Association of University Professors estimates that the benefits package for universities averages 22–23 percent of salary. In a 1987 National Compensation Survey of Research and Development Scientists and Engineers, done by the Hay Management Group for the Department of Energy, the benefits package for government contract laboratories was determined to be 32.8 percent of salaries, and the comparable figure for private and academic laboratories was 29.1 percent. Because of the difficulties in determining total benefits, comparisons are made on base salaries unless specified. |

Chapter 3

REFERENCES

Abramson, M.A. 1988. Statement of Executive Director, Center for Excellence in Government, before Subcommittee on Aviation, U.S. House Committee on Public Works and Transportation. June 22.

Aviation Safety Commission. 1988. Volume I: Final Report and Recommendations. Volume II: Staff Background Papers. USGPO: 1988 0-211-211:QL3.

Department of Health and Human Services. 1988. Need for Decisive Action to Resolve Major Material Weaknesses in Procurement Activity at the National Institutes of Health. Management Advisory Report of the Inspector General to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Washington, D.C.: USDHHS.

General Accounting Office. 1985. Evaluation of Proposals to Alter the Structure of the Senior Executive Service. A Report to the Chairwoman, Subcommittee on Civil Service, House Committee on Post Office and Civil Service. Washington, D.C.: USGAO.

Havermann, J. 1987. Surgeon General Drops Plan to Force 34 Senior NIH Employes to Retire. Washington, D.C.: The Washington Post. June 25.

Industrial Biotechnology Association. 1987. Biotechnology Compensation and Benefits Survey 1987. Washington, D.C.: IBA/Radford Associates.

Institute of Medicine. 1984. Responding to Health Needs and Scientific Opportunity: The Organizational Structure of the National Institutes of Health. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Jolly, P. 1986. Faculty Age Distribution and Research Productivity. Paper presented at Annual Meeting of Association of American Medical Colleges. Washington, D.C.: Association of American Medical Colleges.

Kosterlitz, J. 1988. Bust up a Winning Team? The National Journal, January 9.

Levine, C.H. and R.S.Kleeman. 1986. The Federal Civil Service at the Crossroads. Paper prepared for a conference on “A National Public Service for the Year 2000,” convened by The Brookings Institution and the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research. Washington, D.C.

National Academy of Public Administration. 1983. Revitalizing Federal Management: Managers and Their Overburdened System. Washington, D.C.: NAPA.

National Institutes of Health. 1981. The Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD: NIH. Photocopy.

National Institutes of Health. 1985a. Review of NIH Clinical Center Management Issues. Bethesda, MD: NIH. Photocopy.

National Institutes of Health. 1985b. Report for a Proposed Building for the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Bethesda, MD: NIH. Photocopy.

National Institutes of Health. 1987. Quarterly Space Summary by Organization, December 31. Bethesda, MD: NIH. Photocopy of Tables.

National Institutes of Health. 1988a. Office of the Associate Director for Administration. May. Bethesda, MD: NIH.

National Institutes of Health. 1988b. The Nation’s Commitment to Health Through Biomedical Research—The NIH, the NIH Intramural Research Program and the Pursuit of Scientific Excellence. Bethesda, MD: NIH. Photocopy.

National Institutes of Health. 1988c. Report of the NIH Director’s Task Force on the Shortage of Nurses in the Clinical Center. Bethesda, MD: NIH. Photocopy.

Office of Personnel Management. 1988. Employment and Trends as of March 1988. Federal Civilian Workforce Statistics. Washington, D.C.: OPM.

Panem, S. 1988. The AIDS Bureaucracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic. 1988. Report Submitted to the President of the United States, June 24.

Shilts, R. 1988. And the Band Played On. NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Smith, W.C., Jr. 1988. Report on Medical School Faculty Salaries, 1987–1988. Washington, D.C.: Association of American Medical Colleges.

Spector, M. 1987. Rx for Public Health Service: Uniforms, More Reassignments; Surgeon General Aims to Build ‘Sense of Mission’ in Officer Corps. Washington, D.C.: The Washington Post. April 16.

Stoto, M.A., D.Blumenthal, J.S.Durch, and P.H.Feldman. 1988. Federal funding for AIDS research: Decision process and results in Fiscal Year 1986. Reviews of Infectious Diseases 10(2):406–419.

Volker, P.A. 1988. Public Service: The Quiet Crisis. Presented at the American Enterprise Instituted Francis Boyer Lecture on Public Policy. Washington, D.C.