INTRODUCTION

This study addresses a concern, on the part of some, that the intramural program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), for many years a distinguished component of the nation’s biomedical research effort, faces growing difficulties in attracting and retaining the strong cohort of basic biomedical scientists and clinical investigators needed to ensure continued excellence in research. This concern is often focused on the loss of senior investigators, but similar questions are raised about scientists at more junior levels. There are fears that difficulties in recruiting the outstanding senior scientists whose presence draw junior investigators to NIH may undermine the future vigor of the program.

The Charge to the Committee

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) requested the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) to contract with the National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine (IOM), for a study to evaluate strategies to promote the continued excellence of the NIH intramural laboratories. It was explicitly requested that this study should not confine itself to the question of privatization—a question that had caught the attention of the media and the scientific community.

The charge to the committee was to examine the role of the NIH intramural research program in the nation’s biomedical research enterprise. The committee was asked to determine which characteristics of the program made important contributions that enabled it to accomplish its role and that distinguish it from other biomedical research institutions.

The committee was also asked to examine evidence to determine whether scientific excellence of the program is declining, and what factors might cause it to do so. They were further charged with an examination of alternative approaches to strengthening the program, and were asked to make recommendations that would help sustain the quality of research in the intramural laboratories in the context of changes in the external research environment.

The Committee’s Interpretation of Their Charge

The committee found its charge, as expressed by DHHS, to be well structured. It is important to review the mission or role of the intramural program in the context of the national biomedical research effort to determine whether the program continues to play an appropriate role or whether a change of direction is needed (Chapter 1). Similarly, the committee believes that it is important to discover whether governmental constraints were interfering with the ability of the intramural program’s mission of conducting the highest quality biomedical research (Chapter 2).

The committee has adopted a broad approach to identifying the nature and magnitude of the problems facing the intramural program. In exploring these problems, the committee sought to understand their causes and potential long range effects (Chapter 3). In evaluating alternative solutions to problems, the committee weighed the severity of problems against the risks and advantages of each solution, seeking to ensure that recommendations were targeted to identified problems, while minimizing possible negative side effects (Chapter 4).

It was clear that an examination of a wide range of solutions, including but not confined to privatization, was needed. The committee, therefore, reviewed the advantages and disadvantages of making modest changes in specific administrative problems, as well as the advantages and disadvantages of various types of fundamental organizational restructuring that might offer the promise of greater overall administrative flexibility.

In its recommendations, the committee has tried to move beyond the present to identify future roles for the intramural program, to anticipate future problems, and to recommend solutions with long term validity.

Scope of the Study

In defining the scope of the study, the committee was aware of the limitations imposed by its six-month study period. The principle question addressed is whether a structural change of NIH is needed to solve personnel and other administrative problems that may be interfering with the quality or mission of the intramural program. The committee looked at the mission and quality of the program from the purview of the intramural program. Readers should therefore understand the limitations of a study that did not specifically explore issues surrounding changes in the extramural program, the relationship of NIH as a whole to other agencies in the DHHS, and questions of the distribution of authority and responsibility between the Director of NIH and the directors of the institutes.

In addition, the committee concluded that it was beyond the scope of its charge to determine the optimal size of the intramural program in relation to the nation’s total biomedical research effort. This study, therefore, does not include analysis or recommendations concerning the desirability of transferring resources from one element of the nation’s biomedical research program to another.

Finally, the committee did not view its charge as developing solutions to government-wide personnel problems, which other national commissions are currently investigating. Nevertheless, the committee recognized that it was important to be aware that NIH is not alone in facing problems common to government organizations. Recommendations that would ask for unprecedented freedom from bureaucratic constraints would require that a sound case be made for unique treatment.

Conduct of the Study

During the course of the study the committee held three meetings to address the questions posed in its charge. The committee conducted additional activities to obtain information from many individuals and organizations. On June 13, 1988, the committee held a public hearing at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. limitations were extended to groups concerned with various aspects of biomedical research and health. Approximately 60 people attended the hearing, at which representatives of various organizations and associations addressed the committee. Additionally, the committee received written comments from more than 50 organizations and individuals regarding the NIH intramural program (Appendix A).

To hear the concerns of the community of scientists at NIH, the committee held a meeting at the NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland on May 25, which was attended by scientists of all levels of seniority (Appendix B). Less formally, staff and individual committee members held discussions with a wide array of persons from industry, academia, professional associations, and other organizations with interest in, or valuable views or information on, the issues addressed by the committee.

In addition, the committee commissioned background papers to provide in-depth analyses of topics of particular interest. To broaden their understanding of the structural changes that the committee wished to consider as possible solutions to identified problems, the committee sought advice from the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA). This organization has advised many agencies on matters relating to structural change. Its advice to the committee was reviewed by a panel of experts assembled for that purpose by NAPA.

Yet another source of data was NIH itself, which provided extensive information concerning structure, operations, and procedures.

Finally, because of the severe time constraints of a study limited to six months, the committee could not conduct independent evaluations of some important issues such as the tenure selection process, the quality of postdoctoral fellows, the procurement system, the physical plant, and the work of the laboratories.

Origins of the Study

The concerns that stimulated the OMB and NIH to request this study are hardly new. More than 35 years ago, when NIH employed 2,600 people, ran 7 sets of laboratories, and was building the Clinical Center, the Director of NIH and the Chief of the Research Planning Board noted the following concerns about the intramural program:

Apart from those matters that are of common concern to research administrators in industry, universities, and government, some problems are either unique to government, or appear to be particularly important in government. Federal salary scales are not high. In general, most surveys show that federal pay scales are roughly comparable with industrial scales in the lover and middle bracket. Outstanding people, however, are paid much less than they could earn in private industry (Sebrell and Kidd, 1952).

The authors add that the Civil Service Commission had helped NIH bypass some bureaucratic features of civil service recruitment and compensation, but that rewarding outstanding investigators without moving them into administration remained a problem.

These observations touch on a number of topics that resonate today, and that have been the continued focus of investigations and reports over the years. Two of these bear highlighting:

-

Concern over non-competitive civil service pay and the difficulty of attracting experienced physicians, scientists, nurses, and allied health professionals.

-

Concerns over unnecessary bureaucratic constraints, which are heightened by beliefs that the special nature of scientific work makes inappropriate a civil service, bureaucratic approach to the management of personnel and work environment.

Many of the problems identified in the NIH intramural program are shared with other governmental agencies. Some are particularly acute for the science-based efforts of agencies, and especially acute for NIH, whose primary mission is the conduct of basic and clinical research. There are, however, indications that problems identified by earlier commissions and committees have became more acute in recent years. The following list describes some current concerns and their causes.

-

Micromanagement by the parent department: officials are often reluctant to delegate administrative authority and seek to control programs in inappropriate detail. At NIH, this is observable in many ways, including the requirements that the Office of the Secretary of DHHS approve senior appointments and bonuses, and that the Office of the Chief of Staff of DHHS approve foreign travel.

-

Compensation of personnel: the federal system imposes rigidities and limitations on pay and benefits. The original pay comparability objectives of the government have been eroded, making it more difficult for NIH and other agencies to compete for some categories of personnel, notably high level research scientists and scientific managers.

-

Merit recognition: the prevailing federal payment system is frequently criticized as providing little opportunity to recognize individual abilities and outstanding accomplishment. In addition, managers at NIH and other agencies with scientific personnel note that performance measures are better suited to appraising the work of administrative, rather than scientific, personnel.

-

Retirement statutes: federal retirement plans that cannot be completely interchanged with private sector retirement plans create a disincentive for potential mid- and late-career recruits to become federal employees at NIH.

-

New appointments: delays in securing approval from the Office of Personnel Management for new appointments in the competitive civil service cause agencies, including NIH, to lose promising recruits to more flexible employers.

-

Personnel ceilings: imposing personnel ceilings, in addition to overall budget constraints, makes little management sense in most agencies. NIH managers feel they would be more effective if they could allocate their financial resources in ways they determine as best fulfilling their agency’s mission.

-

Contracting out and procurement: over the years, federal acquisition regulations and controlling statutes have became more onerous—often as a response to perceptions of bad or fraudulent management. While understanding the need for fiscal responsibility, scientists are anxious to preserve a procurement process that is responsive to the needs of biomedical research.

Numerous groups have analyzed these and other problems and have made recommendations. Some that have addressed problems of civil service pay and reform include the Hoover Commission, the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978, and currently the National Commission on the Public Service, under the chairmanship of Paul Volker. Government laboratories have been the focus of some investigations such as the White House Science Council Report of the Federal Laboratory Review Panel (U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy, 1983), and NIH, specifically, has been the focus of attention of other groups, such as the report of the President’s Biomedical Research Panel (1976), the Institute of Medicine (1984), and self-examinations by NIH. Recommendations made by such groups, of which only the first has been implemented, include:

-

Establishment of Senior Executive Service, 1978.

-

Proposed pay increases for Levels I through V of the Executive Branch, ranging from approximately 50 to 80 percent (Report of the Commission on Executive, Legislative, and Judicial Salaries, 1986).

-

Creation of a scientific/technical personnel system independent of current civil service system (U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy, 1983).

-

Creation of a Senior Biomedical Research Service, with supplemental pay up to 110 percent of Executive Level I, and allowance of transfer of participation in the Teachers Insurance Annuity Association-College Retirement Equities Fund (TIAA-CREF) for recruits from universities (NIH, 1987).

The ultimate concern of all these studies has been to enable agencies to accomplish their missions more effectively. Superior staff, responsible oversight, and freedom from micromanagement, are generally deemed necessary to achieve this goal.

Structure and Funding of NIH and Its Intramural Program

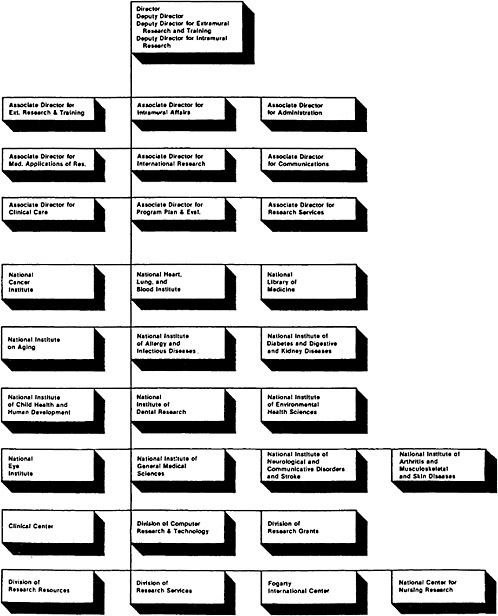

NIH is currently composed of the Office of the Director, twelve research institutes, one research center (National Center for Nursing Research), the Fogarty International Center (which facilitates international research collaboration), the Clinical Center (a research hospital and laboratory complex where the research institutes have allocated beds), the Division of Research Grants (which administers the scientific review of extramural grants), three service divisions (Computer Research and Technology, Research Resources, and Research Services), and the National Library of Medicine (Figure I-1).

As the organizational chart indicates, the Office of the Director of NIH includes deputies for the principal functions of NIH—extramural research and training, and intramural research. The Director of NIH receives recommendations from the Advisory Committee to the Director of NIH, whose members are appointed by the Secretary of DHHS. This group meets twice a year and is also charged with advising the Secretary and the Assistant Secretary of DHHS on matters concerning NIH.

NIH grew from a $3 million enterprise, immediately after World War II, to an organization with a budget today of over $6 billion. Appropriations for NIH grew rapidly in the immediate post-war years. In 1948, a rapid period of growth of new institutes began with the establishment of the National Heart Institute and the National Institute of Dental Research. The growth of categorical institutes was, in part, the result of lobbying by outside groups—voluntary health associations and professional scientific societies. During the mid-1950s, NIH Director James Shannon developed a close relationship with congressional leadership and rapid expansion occurred, continuing into the 1960s. The budget passed the $1 billion mark in 1966, doubled in the following six years, and after a pause in the early 1970s, reached $4 billion in 1983.

The organizational concept of the institutes does not follow a consistent pattern—some are disease related (cancer, diabetes, etc.), some are organ related (heart, lung, eye, etc.), while others are related to fields of science (general medical, environmental health, etc.). The study sections that provide peer review of extramural grants are structured by science fields and, therefore, usually review grants for more than one institute because of overlap of science among institutes (Morris, 1984).

Typically, each institute is under the oversight of its own advisory council whose membership is drawn from outside NIH. This council approves all extramural grants, reviews the institutes’ programs, and advises institute and NIH directors and the Secretary and Assistant Secretary of DHHS. Each institute has an extramural and intramural program headed by a director whose office resembles that of the Director of NIH—containing an office of administration, program planning and evaluation, communications, and other functions.* Institute directors control the policies and programs of their institute (Morris, 1984). Scientific directors supervise and shape the intramural research program, play important roles in assessing the performance of the intramural laboratories in their institutes, act to address problems in the working environment, and serve as a conduit for the scientific advice from intramural investigators to

government decision-makers. Each research institute, the National Center for Nursing Research, the Division of Research Resources, the Fogarty Center, and the National Library of Medicine receive individual annual congressional appropriations, and their activities are closely monitored by congressional authorizing and appropriating committees, as well as by interest groups and professional associations.

The National Cancer Act of 1971, in replacing the original 1937 authority, established some characteristics that distinguish the National Cancer Institute (NCI) from other institutes in the following ways:

-

Giving the NCI bureau status enabled the institute to create its four divisions. The divisions represent major program elements—biology and diagnosis, etiology, prevention and control, and treatment. Each division is headed by a director who has responsibility for both the extramural and intramural programs. In other institutes a single intramural program is guided by a scientific director.

-

The Director of NCI is appointed by the President and is advised by the National Cancer Advisory Board. Under this new structure, the NCI budget process bypasses the Director of NIH and the Secretary of DHHS, going directly to the President. This offers opportunities to make the case for NCI’s budget directly to the administration.

-

The NCI director has administrative latitude that other directors do not have, such as decisions concerning construction projects and the authority to appoint membersof the NCI Board of Scientific Counselors.

The total NIH budget in FY 1988 amounted to $6.7 billion, an increase of 160 percent over the $2.58 billion 1977 budget (NIH, 1988). In constant dollars (deflated by the NIH biomedical research and development price index), the increase from 1977 to 1987 amounted to 20 percent, an average annual growth rate of 1.8 percent. The intramural program represents approximately 11 percent ($700 million) of the NIH budget. The vast majority of the remaining money (about 85 percent), is distributed to the for-profit and non-profit research sectors through grants and contracts.

In many ways, however, it is more useful to consider the budgets of the 12 separate institutes. As Table I-1 shows, institutes vary in size, and in their rates of growth over the last decade. The NCI, with a 1987 budget of $1.4 billion (23 percent of the total NIH budget and 31 percent of the intramural program full-time equivalent employees), is by far the largest institute. After a period of explosive growth between 1970 and 1976, when its budget more that tripled, the NCI budget grew more slowly (about 6 percent per annum over the next decade).

The magnitude of each institute’s intramural program that is carried out within NIH laboratories depends on a number of factors: the size of the particular institute’s overall budget, the share of the budget allocated to the program, and the proportion of the intramural budget used to support activities in NIH laboratories versus contract activities (the latter in some institutes such as NCI can be large).

The agenda of the intramural program is under the direction of the institute director and the scientific director of each institute or division. The scientific directors* (who report to the director of their institute), can exercise a high degree of control over the institute’s intramural program, with oversight provided by the institute’s Board of Scientific Counselors, whose members are appointed from outside NIH. The Deputy Director for Intramural Research at NIH manages scientific policy problems and represents the intramural program of the institutes in aggregate in the overall policy councils of NIH.

In sum, NIH is a highly decentralized organization with numerous entities established by acts of Congress, each with its own appropriations that function with some considerable degree of independence.

TABLE I-1 NIH OBLIGATIONS BY INSTITUTE 1977–1987 (DOLLARS IN MILLIONS)*

|

|

1977 |

1978 |

1979 |

1980 |

1981 |

1982 |

1983 |

1984 |

1985 |

1986 |

1987 |

% Change 1977–87 |

|

Total NIH (Current) |

$2,582 |

2,828 |

3,185 |

3,429 |

3,572 |

3,643 |

4,013 |

4,493 |

5,121 |

5,297 |

6,175 |

139% |

|

Total NIH (Constant 1977) |

2,582 |

2,633 |

2,740 |

2,675 |

2,519 |

2,362 |

2,438 |

2,563 |

2,764 |

2,734 |

3,101 |

20 |

|

% Intramural |

9.6 |

10.1 |

10.8 |

11.1 |

11.6 |

12.4 |

12.3 |

11.4 |

11.2 |

10.8 |

10.8 |

|

|

NCI |

815 |

872 |

937 |

998 |

989 |

986 |

987 |

1,081 |

1,178 |

1,210 |

1,403 |

72 |

|

% Intramural |

12.6 |

13.4 |

13.9 |

14.4 |

15.7 |

17.2 |

18.2 |

17.2 |

16.5 |

17.3 |

17.5 |

|

|

NHLBI |

396 |

448 |

510 |

527 |

550 |

560 |

624 |

706 |

803 |

822 |

930 |

135 |

|

% Intramural |

8.2 |

7.8 |

8.0 |

7.4 |

7.9 |

8.6 |

9.3 |

8.6 |

7.4 |

7.3 |

6.8 |

|

|

NIDR |

55 |

62 |

65 |

68 |

71 |

72 |

79 |

88 |

100 |

99 |

118 |

145 |

|

% Intramural |

19.2 |

20.0 |

19.3 |

19.1 |

19.5 |

20.8 |

21.4 |

21.4 |

19.7 |

19.8 |

20.6 |

|

|

NIADDK |

219 |

260 |

303 |

340 |

369 |

368 |

413 |

464 |

539 |

436** |

511 |

133 |

|

% Intramural |

14.1 |

13.1 |

12.4 |

11.9 |

12.5 |

12.9 |

12.6 |

11.9 |

11.0 |

11.5 |

11.3 |

|

|

NINCDS |

155 |

177 |

212 |

241 |

252 |

265 |

296 |

336 |

396 |

414 |

490 |

216 |

|

% Intramural |

15.0 |

15.5 |

14.6 |

14.3 |

14.1 |

14.8 |

14.5 |

14.1 |

12.7 |

11.6 |

11.2 |

|

|

NIAID |

140 |

162 |

191 |

214 |

232 |

236 |

279 |

320 |

370 |

367 |

545 |

289 |

|

% Intramural |

19.8 |

19.9 |

18.2 |

17.3 |

17.7 |

18.2 |

19.7 |

17.3 |

15.9 |

15.8 |

13.2 |

|

|

NIGMS |

205 |

230 |

277 |

312 |

333 |

340 |

370 |

416 |

481 |

493 |

571 |

178 |

|

% Intramural |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

|

|

NICHHD |

145 |

166 |

197 |

208 |

220 |

226 |

254 |

275 |

313 |

308 |

367 |

153 |

|

% Intramural |

10.7 |

11.3 |

10.5 |

10.3 |

11.5 |

11.5 |

12.4 |

12.5 |

12.2 |

11.3 |

11.2 |

|

|

NEI |

64 |

85 |

105 |

110 |

118 |

130 |

142 |

155 |

181 |

186 |

216 |

237 |

|

% Intramural |

11.0 |

9.3 |

8.6 |

9.3 |

9.8 |

9.7 |

10.1 |

10.4 |

10.0 |

8.0 |

8.6 |

|

|

NIEHS |

51 |

64 |

77 |

84 |

93 |

106 |

164 |

180 |

194 |

189 |

209 |

310 |

|

% Intramural |

26.4 |

27.5 |

28.2 |

29.8 |

30.1 |

27.4 |

29.7 |

31.1 |

27.6 |

27.6 |

27.7 |

|

|

NIA |

30 |

37 |

57 |

70 |

75 |

82 |

94 |

115 |

143 |

151 |

177 |

490 |

|

% Intramural |

20.4 |

21.2 |

17.5 |

18.2 |

17.5 |

17.6 |

19.3 |

16.6 |

14.3 |

13.2 |

13.0 |

|

|

NOTE: * Current dollars unless otherwise stated ** Funds transferred to establish Athritis Institute SOURCE: NIH Division of Financial Management, 1988. |

||||||||||||

Introduction: REFERENCES

Report of the Commission on Executive, Legislative, and Judicial Salaries. 1986. Quality Leadership; Our Governments Most Precious Asset. December 15, 1986.

Institute of Medicine. 1984. Responding to Health Needs and Scientific Opportunity; The Organizational Structure of the National Institutes of Health. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Morris, T.D. 1984. The Current Organizational Structure of the National Institutes of Health. A background paper for the Institute of Medicine report Responding to Health Needs and Scientific Opportunity; The Organizational Structure of the National Institutes of Health. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

National Institutes of Health. 1987. NIH Almanac. NIH Publication No. 87-5. Bethesda, MD: NIH Division of Public Information.

National Institutes of Health. 1988. Office of the Associate Director for Administration. Bethesda, MD: NIH. May.

Report of the President’s Biomedical Research Panel. 1976. Submitted to the President and the Congress of the United States. DHEW Publication No. (OS) 76-500.

Sebrell, W.H. and C.V.Kidd. 1952. Administration of research in the National Institutes of Health. The Scientific Monthly. (March): 152–161.

U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy. 1983. Report of the White House Science Council, Federal Laboratory Review Panel. Washington, D.C.: Executive Office of the President.